Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) belong to diverse family of Herpesviridae, causing oral herpes lesions (HSV-1), genital lesions (HSV-2), meningitis, and encephalitis.[1] Primary infection within the genital tract, followed by an established latency phase give rise to life-long infection in humans.[2] Treatment of herpes infection is thus cause of major concern owing to the difficulty in eliminating it from the ganglion, high cost of treatment, increasing drug resistance, and association with HIV-1.[3–7] We investigated the plants selected on the basis of their traditional usage by comparing the disease symptomatology and recommended use from the texts of Ayurveda and used them in the forms as used traditionally. Primary screening of 24 extracts of seven plants was done by cytopathic effect inhibition (CPE) assay followed by dose response, antiviral, and cytotoxicity assay conducted at eight concentrations from 3.125 to 400 μg/ml. Five extracts, Punica granatum aqueous extract (PGAE), peals powder (PGPP), freeze-dried powder (PGFP), Ocimum sanctum methanol extract (OSME), and Azadirachta indica leaves powder (AZLP) demonstrated favorable activity in primary screening. PGFP showed antiviral activity at 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml concentrations followed by PGAE, which showed highest selectivity index (SI) (14 and 12.5) followed by PGFP (7.6 and 12.9). Thus, aqueous extract and freeze-dried powder of P. grantum have potential to be further explored for its possible anti-HSV activity.

The plants selected, namely, A. indica, Curcuma longa, Punica granatum, O. sanctum, Nyctanthes arbortristis, Carica papaya, and Holarrhena antidysentrica were collected from Gujarat State of India. The plant species were taxonomically identified and confirmed using morphological and anatomical techniques. They were authenticated at the Botanical Survey of India, Pune and voucher specimens were deposited and standardized using High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) method (data not provided here) [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

In-vitro screening of plant extracts against HSV-1 and HSV-2

Figure 2.

Twenty-four extracts of seven plants were screened for their antiviral activity in-vitro. The figure depicts the plants and the methodology used for screening

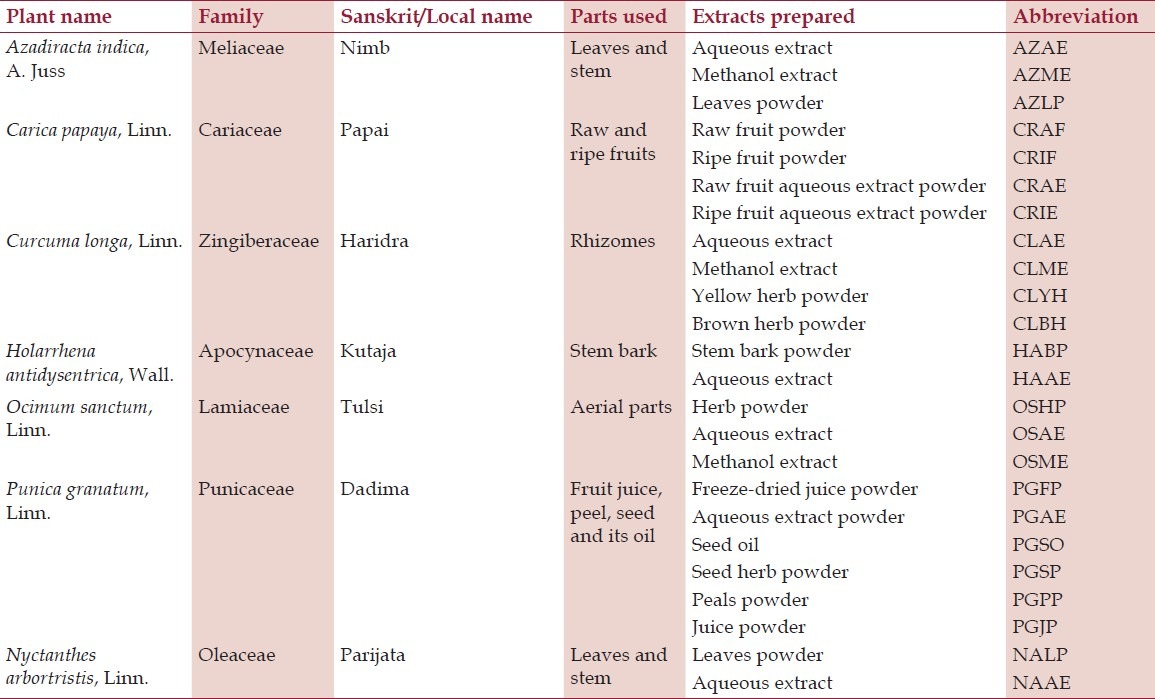

We screened 24 extracts of 7 selected plants, of which 7 were water extracts, 3 were methanol extracts, and 14 were powders of various plant parts [Table 1]. The herb powders were prepared by drying and grinding the plant materials. Water and methanol extracts were prepared from 500 g of fresh raw material of plant parts in Soxhlet extraction vessel under reflux with stirrer for 3 cycles with methanol or water. After each cycle, solvent was added to replenish the remaining volume and dried in a rotatory evaporator at temperature not exceeding 35°C. The stock solution of 20 mg/ml was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) and subsequent serial dilutions were carried out in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) (GIBCO Cat. No. 12430) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GIBCO Cat. No. 16000-044). The final concentration of DMSO was <0.2%.[8]

Table 1.

Details of the plant and their extracts screened against herpes virus

All reagents and media for cell culture were purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). Confluent monolayer of African Green Monkey kidney cell line (Vero) (ATCC CCL-81) was grown in T-25 flasks in a 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) incubator at 37°C for 48 hours, in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin G sodium 200 U/ml, streptomycin sulfate 200 mg/L, and amphotericin B 0.5 mg/L. HSV-1 clinical strain and HSV-2 ATCC G strain virus stocks were propagated in Vero cells and used at a titer of 1:10,000 for HSV-1 and 1:1000 for HSV-2 in all in-vitro experiments.

Acyclovir (ACV) powder (Matrix Laboratories Limited, Hyderabad, India) was used as a standard antiviral drug at four different concentrations: 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, and 25 μg/ml for HSV-2 and 0.78, 1.56, 3.125, 6.25, and 12.5 μg/ml for HSV-1. It was dissolved with DMSO to give a stock concentration of 10 mg/ml and then diluted with DMEM-2% FBS (maintenance medium) before use. For all the assays, ACV control consisted of the cells, ACV at different concentrations: 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, and 25 μg/ml for HSV-2 and 0.78, 1.56, 3.125, 6.25, and 12.5 μg/ml for HSV-1 made by 1:2 serial dilutions and the virus suspension.

Primary screening of these extracts was conducted by CPE assay at 100 μg/ml concentration against HSV-2 in triplicates. Confluent Vero cells were grown in 96-well microtiter plates (2 × 104 cells/100 μl) for 24 hours. Two-fold serial dilutions of the samples were prepared in DMEM with 2% FBS. The cell control consisted of 200 μl maintenance medium; the virus control consisted of 100 μl of maintenance medium and 100 μl of the virus suspension. After 1 hour incubation of the cells with different sample concentrations, the virus (HSV-2) was added to the plates and the plates were again incubated for 48 hours in 5% CO2 at 37°C. The plates were then washed with saline and stained with crystal violet and incubated for 30 min at room temperature after which the plates were gently washed under running tap water and left overnight for drying and visually analyzed (qualitatively).[9]

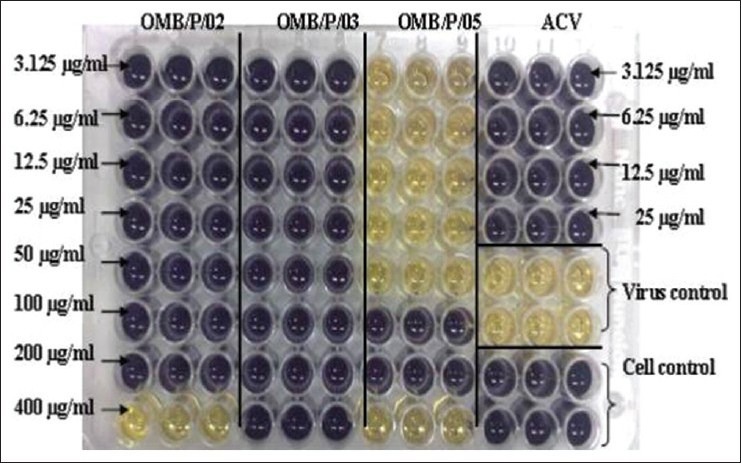

Eight concentrations of extracts that exhibited activity in CPE assay were assayed from 3.125 μg/ml onwards higher in the ratio 1:2 till 400 μg/ml. After 1 hour incubation of test samples with the cells, virus was added and the plates were incubated for 48 hours before washing with saline and staining with crystal violet. After overnight drying, the plates were analyzed.[10,11]

The extracts that exhibited activity in CPE assay were analyzed at eight concentrations for antiviral assay. The assay plates contained virus and cell controls and the samples. The plates were then incubated for 48 hours after which the plates were washed with plain DMEM followed by the addition of tetrazolium compound MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) reagent diluted 1:10 in 2% FBS-DMEM. After incubation of 4 hours, detergent was added to the wells and left overnight for incubation in a 5% CO2 at 37°C. The absorbance was then read with the help of a plate reader at a wavelength of 570 nm. The data were analyzed by plotting cell number versus absorbance, allowing quantification of changes in cell proliferation.[12,13]

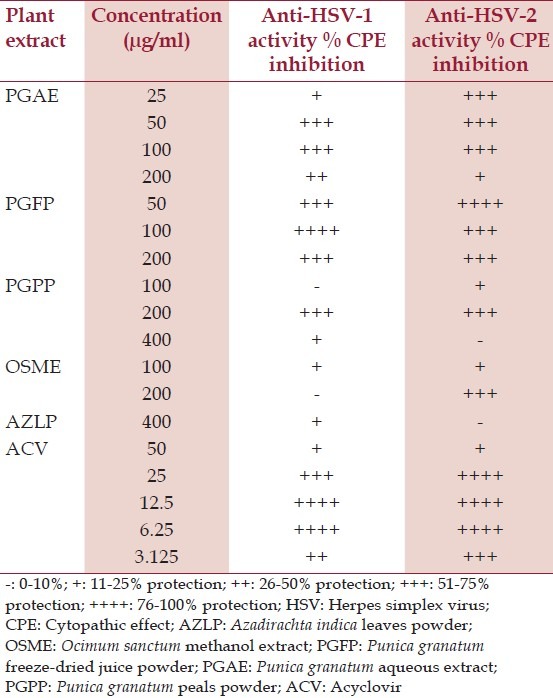

CPE assay and dose response assay

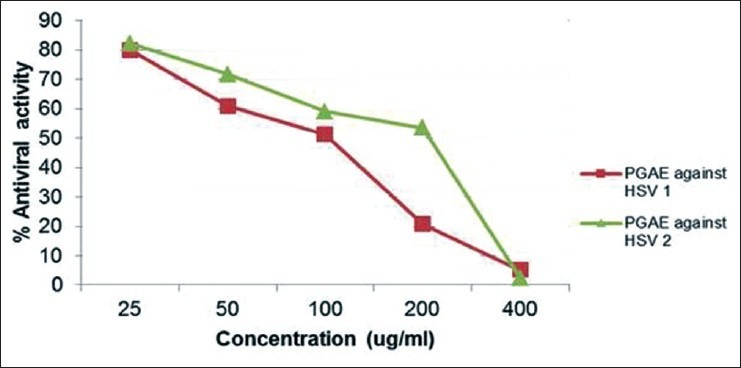

Extracts PGAE, PGPP, PGFP, OSME, and AZLP exhibited positive response in the CPE assay [Table 2] and were further screened at eight concentrations [Figure 3a]. All the three Punica grantum extracts showed a dose-dependent response against both HSV-1 and HSV-2 along with OSME. Based on the SI values, PGFP showed the most potent antiviral activity (CC50: 233 μg/ml, IC50: 30.6 and 18.14 μg/ml and SI: 14 and 12.5 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively) at 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml concentrations followed by PGAE (CC50: 220 μg/ml, IC50: 15.8 and 17.6 μg/ml and SI: 7.6 and 12.9 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively). OSME and PGPP showed identical antiviral activity. AZLP failed to exhibit any significant antiviral activity [Table 3].

Table 2.

Primary screening results of the samples against HSV-2 at 100 μg/ml

Figure 3a.

Dose response analysis of samples 1 (OSME), 2 (PGAE), 3 (PFFP), 4 (PGPP), and 5 (AZLP) along with acyclovir (ACV), HSV-2 virus control and cell controls in a 96-well plate following CPE inhibition assay

Table 3.

Dose response assay outcome of selected extracts

Antiviral and cytotoxicity assay

To assess the antiviral potential and cytotoxicity of PGAE, PGPP, PGFP, and OSME, MTT was performed with and without the virus [Figure 3b]. Following formulae were used as described by Cheng, et al. (2004):[13]

Figure 3b.

MTT plate for samples: PGAE, PGFP, and PGPP assayed in a dose-dependent manner against HSV-2. Yellow indicates extremely low cell density due to plaque formation and deep purple indicates high cell density

Table 4 illustrates the percentage (%) viability, % toxicity, and % antiviral activity of these four extracts. From this study, based on the CC50 values, it can be concluded that all the five samples showed no cytotoxicity at the potent antiviral concentrations. Based on the results, it was found that PGAE [Figure 4a] showed the highest SI (14 and 12.5); therefore, the promising antiviral activity against HSV-1 and HSV-2, is followed by PGFP (7.6 and 12.9) [Figure 4b], whereas PGPP and OSAE showed moderate SIs [Table 4].

Table 4.

Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity effect of selected extracts

Figure 4a.

Antiviral activity of PGAE against HSV-1 and HSV-2

Figure 4b.

Antiviral activity of against HSV-1 and HSV-2

Discussion

We attempted to generate the in-vitro data of activity for the plants and their extracts against herpes virus using similar drug formulations as used traditionally. The preliminary data of the selected plants and their extracts’ antiviral activity based on in-vitro studies were not available to the extent of our knowledge. Five out of 24 extracts showed potential antiviral activity against HSV-2 at 100 μg/ml. Based on these results, further qualitative and subsequent quantitative analyses of these positive samples were carried out at a wider concentration range. In order to confirm that the inhibitory effect of the extracts seen was due only to its antiherpes activity and not due to overlapping drug toxicity itself, the cytotoxicity assay was carried out to measure cell viability in presence of the drug alone.

A. indica A. Juss aqueous and methanol extract, O. sanctum, Linn. herb powder and aqueous extract, Punica granatum, Linn. seed oil, seed herb powder and juice powder and samples of C. papaya, Linn., C. longa, Linn., H. antidysentrica, Wall., and Nyctanthes arbortristis, Linn. failed to exhibit anti-HSV potential in primary screening at a concentration of 100 μg/ml against HSV-2.

There are no preliminary data on antiherpes studies on C. papaya, H. antidysentrica, and N. arbortristis. Although H. antidysentrica has demonstrated activity against various infective pathogens as antimalarial, antibacterial, anti-Escherichia coli, and anti-MRSA agent.[14–17] N. arbortristis is reported for its antileishmanial, antiinflammatory, and antiencephalitis causing virus activity.[18–22] A. indica Linn. bark aqueous extract demonstrated potent entry inhibitor activity against HSV-1 infection.[23] A. indica A. Juss aqueous extract and its pure compound Azadirachtin were studied against dengue cirus type-2. The crude aqueous extract revealed inhibition in a dose-dependent response in-vitro and in-vivo, whereas pure compound Azadirachtin failed to exhibit any activity against the virus.[24] Neem oil was assayed against HSV-1, which did not demonstrate antiviral activity.[9] Although no studies were found on C. longa, but the isolate curcumin exhibited potent antiviral potential against HSV-1 and HSV-2.[25–27] O. basilicum aqueous and ethanol extracts and isolate ursolic acid exhibited potent anti-HSV-1 activity in-vitro.[28] Ursolic acid is one of the important marker compounds of O. sanctum.[29] The aqueous extract and tannins from pericarp of P. granatum had shown anti-HSV-1 and HSV-2 activities in-vitro, respectively.[30,31]

Other plants mentioned in texts of Ayurveda were shown to have anti-HSV activity. Acetone, ethanol, and methanol extracts of Phyllanthus urinaria Linn. inhibited HSV-2 infection by disturbing the early stage of virus infection and by diminishing the virus infectivity.[32] Another Indian medicinal plant extract Swertia chirata inhibited HSV-1 viral dissemination.[33] Putranjivain A, isolate of Euphorbia jolkini Bioss, inhibited both the virus entry and late stage replication of HSV-2 in-vitro.[13] Kenyan plant Carissa edulis aqueous extract exhibited efficacy against both in-vitro and in-vivo models of HSV-1 infection.[34]

This study highlights the potential of these investigated plant extracts to be exploited for antiviral activity.[35] The aqueous extract and freeze-dried powder of P. grantum exhibited promising antiviral activity. The punicalagin present in extract and juice of P. granatum may be explored further for bioactivity guided fractionation studies.[36,37] The remaining extracts may have compounds of antiviral potential, which may be present at quantities insufficient to inactivate all infectious virus particles. It is possible that the elucidation of active constituents in these plants may provide important lead to the development of new and effective antiviral agents.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Manoj P. Jadhav, for his valuable inputs and timely suggestions during the course of this study.

References

- 1.Connolly SA, Jackson JO, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. Fusing structure and function: A structural view of the herpesvirus entry machinery. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:369–81. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed HJ, Mbwana J, Gunnarsson E, Ahlman K, Guerino C, Svensson LA, et al. Etiology of genital ulcer disease and association with human immunodeficiency virus infection in two tanzanian cities. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:114–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kropp RY, Wong T, Cormier L, Ringrose A, Burton S, Embree JE, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in Canada: Results of a 3-year national prospective study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1955–62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celum C, Wald A, Hughes J, Sanchez J, Reid S, Delany-Moretlwe S, et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:2109–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, Changalucha J, Baisley K, Mugeye K, et al. Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1560–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corey L, Handsfield HH. Genital herpes and public health: Addressing a global problem. JAMA. 2000;283:791–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert M, Li X, Petric M, Krajden M, Isaac-Renton JL, Ogilvie G, et al. Using centralized laboratory data to monitor trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infection in British Columbia and the changing etiology of genital herpes. Can J Public Health. 2011;102:225–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03404902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta M, Shaw BP, Mukherjee A. A new glycosidic flavonoid from Jwarhar mahakashay (antipyretic) Ayurvedic preparation. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:106–11. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.64401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayan P, Raghu C, Ashok G, Dhanaraj SA, Suresh B. Antiviral activity of medicinal plants of Nilgiris. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng HY, Huang HH, Yang CM, Lin LT, Lin CC. The in vitro anti-herpes simplex virus type-1 and type-2 activity of Long Dan Xie Gan Tan, a prescription of traditional Chinese medicine. Chemotherapy. 2008;54:77–83. doi: 10.1159/000119705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zu Y, Fu Y, Wang W, Wu N, Liu W, Kong Y, et al. Comparative study on the antiherpetic activity of aqueous and ethanolic extracts derived from Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp. Forsch Komplementmed. 2010;17:15–20. doi: 10.1159/000263619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin CW, Wu CF, Hsiao NW, Chang CY, Li SW, Wan L, et al. Aloe-emodin is an interferon-inducing agent with antiviral activity against Japanese encephalitis virus and enterovirus 71. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng HY, Lin TC, Yang CM, Wang KC, Lin LT, Lin CC. Putranjivain A from Euphorbia jolkini inhibits both virus entry and late stage replication of herpes simplex virus type 2 in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:577–83. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma G, Dua VK, Agarwal DD, Atul PK. Anti-malarial activity of Holarrhena antidysenterica and Viola canescens, plants traditionally used against malaria in the Garhwal region of north-west Himalaya. Malar J. 2011;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavitha D, Niranjali S. Inhibition of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion on host epithelial cells by Holarrhena antidysenterica (L.) WALL. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1229–36. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aqil F, Ahmad I. Antibacterial properties of traditionally used Indian medicinal plants. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2007;29:79–92. doi: 10.1358/mf.2007.29.2.1075347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aqil F, Ahmad I, Owais M. Evaluation of anti-methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) activity and synergy of some bioactive plant extracts. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:1093–102. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shukla AK, Patra S, Dubey VK. Deciphering molecular mechanism underlying antileishmanial activity of Nyctanthes arbortristis, an Indian medicinal plant. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:996–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das S, Sasmal D, Basu SP. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity of arbortristoside-A. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathore B, Paul B, Chaudhury BP, Saxena AK, Sahu AP, Gupta YK. Comparative studies of different organs of Nyctanthes arbortristis in modulation of cytokines in murine model of arthritis. Biomed Environ Sci. 2007;20:154–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta P, Bajpai SK, Chandra K, Singh KL, Tandon JS. Antiviral profile of Nyctanthes arbortristis L. against encephalitis causing viruses. Indian J Exp Biol. 2005;43:1156–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tandon JS, Srivastava V, Guru PY. Iridoids: A new class of leishmanicidal agents from Nyctanthes arbortristis. J Nat Prod. 1991;54:1102–4. doi: 10.1021/np50076a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiwari V, Darmani NA, Yue BY, Shukla D. In vitro antiviral activity of neem (Azardirachta indica L.) bark extract against herpes simplex virus type-1 infection. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1132–40. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parida MM, Upadhyay C, Pandya G, Jana AM. Inhibitory potential of neem (Azadirachta indica Juss) leaves on dengue virus type-2 replication. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:273–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zandi K, Ramedani E, Mohammadi K, Tajbakhsh S, Deilami I, Rastian Z, et al. Evaluation of antiviral activities of curcumin derivatives against HSV-1 in Vero cell line. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5:1935–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutluay SB, Doroghazi J, Roemer ME, Triezenberg SJ. Curcumin inhibits herpes simplex virus immediate-early gene expression by a mechanism independent of p300/CBP histone acetyltransferase activity. Virology. 2008;373:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bourne KZ, Bourne N, Reising SF, Stanberry LR. Plant products as topical microbicide candidates: Assessment of in vitro and in vivo activity against herpes simplex virus type 2. Antiviral Res. 1999;42:219–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang LC, Ng LT, Cheng PW, Chiang W, Lin CC. Antiviral activities of extracts and selected pure constituents of Ocimum basilicum. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:811–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anandjiwala S, Kalola J, Rajani M. Quantification of eugenol, luteolin, ursolic acid, and oleanolic acid in black (Krishna Tulasi) and green (Sri Tulasi) varieties of Ocimum sanctum Linn. using high-performance thin-layer chromatography. J AOAC Int. 2006;89:1467–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Zhan B, Yao X, Gao Y, Shong J. Antiviral activity of tannin from the pericarp of Punica granatum L. against genital Herpes virus in vitro. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1995;20:556–8. 576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Ooi LS, Wang H, But PP, Ooi VE. Antiviral activities of medicinal herbs traditionally used in southern mainland China. Phytother Res. 2004;18:718–22. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang CM, Cheng HY, Lin TC, Chiang LC, Lin CC. Acetone, ethanol and methanol extracts of Phyllanthus urinaria inhibit HSV-2 infection in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2005;67:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verma H, Patil PR, Kolhapure RM, Gopalkrishna V. Antiviral activity of the Indian medicinal plant extract Swertia chirata against herpes simplex viruses: A study by in-vitro and molecular approach. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:322–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tolo FM, Rukunga GM, Muli FW, Njagi EN, Njue W, Kumon K, et al. Anti-viral activity of the extracts of a Kenyan medicinal plant Carissa edulis against herpes simplex virus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan MT, Ather A, Thompson KD, Gambari R. Extracts and molecules from medicinal plants against herpes simplex viruses. Antiviral Res. 2005;67:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin LT, Chen TY, Chung CY, Noyce RS, Grindley TB, McCormick C, et al. Hydrolyzable tannins (chebulagic acid and punicalagin) target viral glycoprotein-glycosaminoglycan interactions to inhibit herpes simplex virus 1 entry and cell-to-cell spread. J Virol. 2011;85:4386–98. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01492-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu J, Wei Y, Yuan Q. Preparative separation of punicalagin from pomegranate husk by high-speed countercurrent chromatography. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;857:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]