Abstract

Hedychium spicatum (Ham-ex-Smith), known as Shati in Ayurvedic classics, is documented for the treatment of cough, hiccough, fever and asthma. The present study includes the evaluation of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the dried rhizome of H. spicatum for anti-histaminic and ulcer-protective activities in guinea pig (GP), anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities in rat and acute toxicity in mouse. The extracts were administered orally, daily as suspension, in 1% carboxymethyl cellulose either for 7 days in GP studies or 60 min before or just before experiment in rats and mice. An initial dose-dependent anti-histaminic action of both the extracts (100, 200 and 400 mg/kg) was performed against histamine-induced bronchospasm in GPs. The 200 mg/ kg dose of aqueous and ethanolic extracts was selected both in GP and rat for further studies. GPs treated with aqueous and ethanolic extracts showed gastric ulcer protection against histamine-induced gastric ulcer compared with the control group. Both the extracts also showed an anti-inflammatory effect against carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats from 1 h onwards, and this was maximum at 3 h. Analgesic effect was determined by using hot plate and tail flick tests in rats, and both the extracts at 200 mg/kg showed a significant increase in the latent period from 30 min onwards till 120 min of their study period. Both the extracts did not show any toxic effect like increased motor activity, salivation, clonic convulsion, coma and death in mice even at the 2000 mg/kg dose (nearly 10 times of the optimal effective dose), indicating the safety of the extracts. The result confirms the indigenous use of this plant in respiratory disorders.

Keywords: Analgesic, antihistaminic, anti-inflammatory, Hedychium spicatum, respiratory disorders, ulcer protective

INTRODUCTION

Hedychium spicatum (Ham-ex-Smith) is a perennial rhizomatous herb belonging to the family Zingiberaceae. It grows throughout the subtropical Himalaya in the Indian state of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand within an altitudinal range of 1000–3000 m.[1,2] H. spicatum rhizome is mentioned as Shati in Ayurvedic classics and has been used in various dosage forms to treat cough, wound ulcer, fever, respiratory problems and hiccough. The rhizomes have a strong aromatic odor and bitter taste. In local language, the rhizomes are commonly known as kapur kachari or ban Haldi.[3] Rhizomes are also used as perfume in tobacco and insect repellent.[4] The rhizome extract has been reported to contain essential oil, starch, resins, organic acids, glycosides, albumen and saccharides, which has been advocated for blood purification and treatments of bronchitis, indigestion, eye disease and inflammations.[5,6] Rhizome is reported to contain sitosterol and its glucosides, furanoid diterpene-hedychenone and 7-hydroxyhedychenone and essential oil contains cineole, terpinene, limonene, phellandrene, p-cymene, linalool and terpeneol. The plant rhizomes possess hypoglycaemic, vasodialator, spasmolytic, hypotensive, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.[7] Powdered rhizome of H. spicatum has been used clinically for the treatment of asthma[8] and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia[9] and as anti-inflammatory and analgesic.[10] The present study is a part of ongoing reverse pharmacology where our aim is to study the anti-inflammatory, antihistaminic and analgesic effects of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the dried powdered rhizome of H. spicatum to rationalize the empirical therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The authentic rhizome of H. spicatum (Ham-ex-Smith) was collected from the hills of Uttarakhanda (natural habitat) in the month of October 2010, verified and confirmed by Prof. K. N. Dwivedi, Department of Dravyaguna, Faculty of Ayurveda, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University. The dried rhizomes were powdered in the Ayurvedic Pharmacy of B.H.U. and packed in an air tight container.

Preparation of rhizome extracts

Five hundred grams each of the air-dried rhizome (coarsely powdered) was placed in 1000 mL of double-distilled water (DW) and 500 mL of ethanol, respectively, in two separate closed flasks for 24 h, shaking first at an interval of 6 h and then allowed to stand for 18 h. The solutions were filtered and the filtrates were then vacuum dried. The yields of aqueous and ethanolic extract were 7% and 4%, respectively. They were stored in a refrigerator at -20°C until further use.

Animals

Adult healthy guinea pigs (GPs) weighing between 350 and 450 g of either sex were obtained locally from the Zoological Animal Emporium, Varanasi. Adult Charles-Foster strain albino rats and Swiss albino mice of either sex, weighing between 180–200 g and 20–25 g, respectively, were obtained from the Central Animal House of the Institute of Medical Sciences, B.H.U, Varanasi. All animals were kept in colony cages under ideal housing conditions at an ambient temperature of 25°C ± 2°C and 45–55% relative humidity with a 12-h light–dark cycle in the animal house of the pharmacology department and fed on a standard pellet diet. Animals were acclimatized for 1 week before use. Ethical permission for the investigation of animals used in the experiments was taken from the Animal Ethics Committee of the Institute (Notification No. Dean/2006-07/810 dated 25.11. 2006).

Drugs and chemicals

Histamine acid phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, MO, USA), carrageenan (CDH, Central Drug House Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India), chlorpheniramine maleate (CPM, Sun Pharma, Mumbai, India) and indomethacin (IND, Indocap, 25 mg, Jagsonpal, Mumbai, India) were used.

Experimental design

Treatment protocol

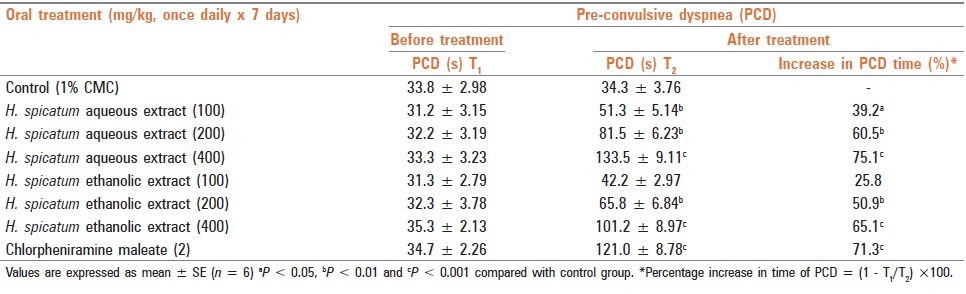

Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the rhizome of H. spicatum were suspended in 1% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) in distilled water. The extracts/CMC was given orally with the help of an orogastric tube in the volume of 1 mL/100 g animal. The dose and duration of treatment are mentioned in the respective study group. A dose–response effect of the two extracts, using doses of 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg, respectively, was performed against histamine-induced bronchospasm in GPs. The pre-convulsive dyspnoea time (PCD) was determined from the time of start of histamine exposure to the onset of dyspnoea, leading to the appearance of convulsions and 200 mg/kg dose of both extracts showing ≥50% increase in the PCD time [Table 1] was then selected for further study both in GPs and in rat after their surface area consideration.

Table 1.

Effects of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of dried rhizome of H. spicatum and chlorphenaramine maleate on histamineinduced bronchospasm in guinea pigs

Histamine-induced bronchospasm[11]

The effects of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts were evaluated against histamine-induced bronchospasm in GP. Bronchospasm was induced in GPs by exposing them to 1% histamine acid phosphate base aerosol under constant pressure (1 kg/cm2) in an aerosol chamber with inbuilt nebuliser (M/s Inco, Ambala, India) made of perplex glass. Eight groups containing six animals each were used for the study. The first group received 1% CMC (negative control), the second to seventh groups received aqueous and ethanolic extracts in the doses of 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg each, respectively, while the eighth group received CPM (positive control) in the dose of 2 mg/kg. All the groups received the respective treatments, orally, once daily for 7 days, and the last dose was given 60 min before experiment to 18-h fasting GP. GPs were placed in the histamine chamber for determining the PCD from the time of start of 1% histamine aerosol under constant pressure (1 kg/cm2) to the onset of dyspnea on Day 0 without any treatment. After the determination of PCD for individual animals, the animals were removed from the chamber and placed in fresh air. The PCD was again recorded on the seventh day, 60 min after the last dose administration of HSW, HSE or CPM as mentioned above. The % increase in time of PCD was calculated using the following formula.[12]

Percentage increase in time of PCD = [1 - T1/ T2] × 100

Where, T1 = time for PCD onset on Day 0 (pretreatment), T2 = time for PCD onset on Day 7 (post-treatment).

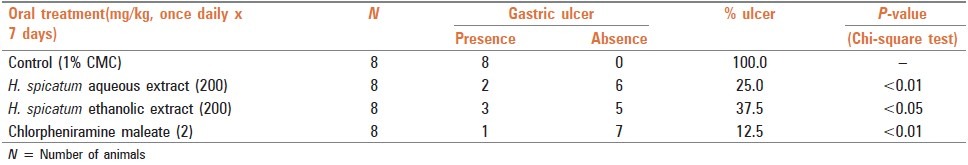

Histamine-induced gastric ulcer[13]

Four groups of GPs, each having eight animals, were used. The control group received 1% CMC and the treated groups received aqueous and ethanolic extracts (200 mg/kg), while the standard group received CPM (2 mg/kg). CMC/test drugs were administered orally, once daily for 7 days. The animals were put on fast on the sixth day for 18 h and the last dose was given 60 min before administration of histamine (5 mg/ kg, intraperitoneal, stat dose) to induce gastric ulcers in the animals on the seventh day of the experiment. After 6 h of histamine administration, the animals were sacrificed by a blow on the head and the abdomen was opened immediately by a midline incision. The stomach as well as the duodenum were examined for the presence of ulcers. No ulcer was observed in the duodenum and the stomach showed the presence of ulcers that were linear and had a circumferential distribution. Chi square test was applied to ascertain the statistical significance of the difference observed in the stomach ulceration in the control and test drug administered groups.

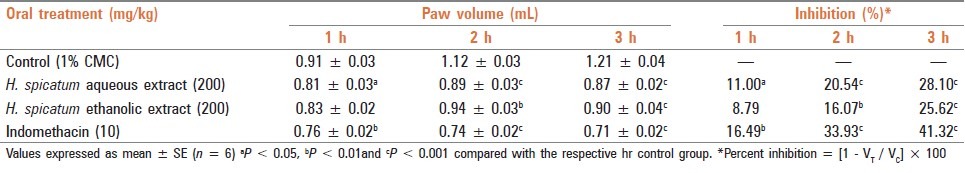

Anti-inflammatory activity[14]

A total of four groups of rats having six animals each were used for the study. The control group received 1% CMC and the treated groups received a single dose of aqueous and ethanolic extracts (200 mg/kg) and IND (10 mg/kg) orally, 60 min before carrageenan administration in 18-h fasted rats. Carrageenan suspension was prepared as a homogenous 1% suspension of the powder in 0.9% sodium chloride solution (sterile normal saline). The volume of rat hind paw up to the ankle joint was measured plethysmographically by the mercury displacement method just after administration of 0.1 mL of 1% carrageenan (0 h) in all the above treated groups. The paw volume was further recorded in a successive interval of 1 h, 2 h and 3 h, respectively. Percent inhibition in paw volume between the treated and the control groups were calculated as follows:

Percent inhibition = [1 - VT/ VC] × 100

Where, VT and VC were the mean paw volumes of the treated and control groups, respectively, at 1, 2 or 3 h.

Analgesic effect[15]

Four groups of animals each having six rats were used for the study. Anti-nociceptive effect was determined using the tail flick test with the help of an analgesiometer and the animals showing positive response (tail withdrawal) within 4–6 s were selected for the study. The control group received 1% CMC while the treated groups received single doses of aqueous and ethanolic extracts (200 mg/kg) and IND (10 mg/kg) orally at the time of the experiment to 18-h fasted animals. Anti-nociceptive effect was observed at 0 min (before treatment) and at every 30 min to 120 min after the administration of test extracts/IND/CMC. Percent increase in analgesic activity between the treated and the control groups was calculated as follows:

Percentage increase in analgesic time = [1 - TC/ TT] × 100

Where, TC = mean latent period time of control, TT = mean latent period time of treated groups, respectively, at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min.

Acute toxicity study[16]

Adult Swiss strain albino mice of either sex, weighing between 20 and 25 g, fasted overnight, were used for the toxicity study. Suspension of aqueous and ethanolic extracts was orally administered at 2 g/kg stat dose (10 times of the optimal effective dose of 200 mg/kg) to mice. Subsequent to extracts administration, animals were observed closely for the first 3 h, for any toxicity manifestation, like increased motor activity, salivation, convulsion, coma and death. Subsequently, observations were made at regular intervals for 24 h. The animals were under further investigation up to a period of 1 week.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparison was performed using Chi square Test for GP gastric ulcer study and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's “t” test for multiple comparisons in other studies.

RESULTS

Histamine-induced bronchospasm

Graded doses (100, 200 and 400 mg/kg) of both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of H. spicatum dried rhizome when administered orally, once daily, to GPs for 7 days, indicated dose-dependent protection against histamine-induced bronchospasm in terms of increase in PCD time from 39.2 to 75.1% (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001) and 25.8 to 65.1% (P < 0.1 to P < 0.001), respectively, while CPM showed an increase by 71.3% (P < 0.001). The result indicated comparable effects of both the extracts with CPM, a known H1 blocker [Table 1].

Histamine-induced gastric ulcer

Both aqueous and ethanolic extracts (200 mg/kg) when administered orally, once daily, to GP for 7 days showed protection against histamine-induced gastric ulcer (H1 m mediated) in GP, and the result showed comparable effects of both the extracts with CPM, a known H1 blocker [Table 2].

Table 2.

Gastric ulcer (GU) protective effect of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of dried rhizome of H. spicatum and CPM against histamine-induced gastric ulcers in guinea pigs

Anti-inflammatory activity

Both aqueous and ethanolic extracts (200 mg/kg) and IND (10 mg/kg) were administered orally to rats 60 min before carrageenan administration. They showed a significant decrease in paw volume against carrageenan-induced inflammation from 1 h onwards to 3 h of the study period (% decrease in inflammation aqueous extract - 11.00–28.10%; ethanolic extract - 8.79–25.62%; IND - 16.49–41.32%, respectively) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Anti-inflammatory effect of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of dried rhizome of H. spicatum and indomethacin against carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats

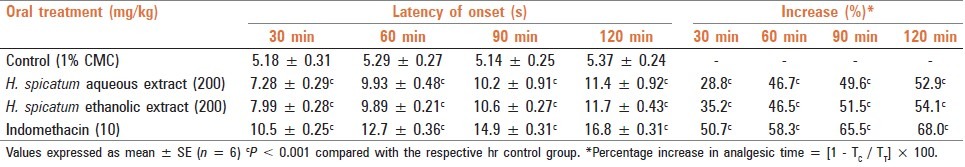

Analgesic effect

Both aqueous and ethanolic extracts (200 mg/kg) and IND (10 mg/kg), when administered orally to rats before experiment, showed significant analgesic activity from 30 min onwards till 120 min of the study period (% increase in latent period aqueous extract - 28.8–52.9%; ethanolic extract - 46.5–54.1%; IND - 50.7–68.0%) [Table 4]

Table 4.

Analgesic effect of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of dried rhizome of H. spicatum and indomethacin on tail flick latency in rats

DISCUSSION

Sati (H. spicatum) is an important medicinal herb. The rhizome has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, vasodilator, spasmolytic, antiasthmatic and hypotensive properties.[17] It is commonly used in various preparations of indigenous medicine for respiratory disorders.[5] Basophils, mast cells and their preformed de novo synthesized mediators like histamine, bradykinin, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, proinflammatory cytokines, etc. play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of allergic disorders.[18,19] The experimental animal model of asthma is characterized by allergen-induced immediate airway constriction and late airway reactivity to a pharmacological vasoconstrictor such as histamine and eicosanoids as they are prominent mediators in the pathogenesis of allergic and inflammatory disorders.[20] In the present study, both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of H. spicatum rhizome caused pronounced increase in the latent period of PCD induced by histamine aerosol and protection against histamine-induced gastric ulcer (H1 mediated).[13]

Inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of asthma; therefore, the anti-inflammatory activity was studied against carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats. The inflammatory condition induced by carageenan involves step-wise release of vasoactive substance such as histamine, bradykinin and serotonin in the early phase and prostaglandin in the acute phase.[21] These chemical substances produce an increase in vascular permeability, thereby promoting accumulation of fluid in tissues that accounts for edema.[22,23] The results of the present study showed that both the extracts possessed anti-inflammatory property as evidenced by inhibition of edema induced by carrageenan. Inflammation itself is associated with pain; therefore, the analgesic activity of H. spicatum was studied by the tail flick latency test in rats. Result showed the presence of analgesic activity in both the extracts. The result thus showed both anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects equally in both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of H. spicatum, indicating its usefulness in asthma.

Rhizome has been reported to contain sitosterol and its glucosides, furanoid diterpene-hedychenone and 7-hydroxyhedychenone, and essential oils like cineole, terpinene, limonene, phellandrene, p-cymene, linalool and terpeneol as major constituents.[24–27] β-sitosterol has been reported to exhibit an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting nuclear factor-kB phosphorylation and vascular adhesion molecule-1 and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in TNF-α-stimulated human aortic endothelial cells[28] analgesic action in rats[29] and antihistaminic, anti-allergic and mast cell stabilizing properties in mice.[30] Essential oils like cineole and terpinene were found to have analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties in animal models.[31,32] It is possible that the extracts of H. spicatum rhizome might have the above properties by virtue of the presence of the above-mentioned chemical constituents, and they may be responsible for the expression of various pharmacological effects useful in asthma and other respiratory disorders.

No harmful effects were observed in the extracts of this plant after acute toxicity study even with 10 times of the effective dose of the extracts, indicating the safety status of this plant.

CONCLUSION

The present study affirms the bronchodilator, anti-histaminic, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the rhizome of H. spicatum important to attenuate bronchoconstriction, inflammation and associated pain and hence prominently seem to validate its traditional use in respiratory inflammatory conditions, including asthma.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Samant SS, Dhar U. Diversity, endemism and economic potential of wild edible plants of Indian Himalaya. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 1997;4:179–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur RS, Puri HS, Hussain A. Lucknow: CIMAP Publication; 1989. Major medicinal plants of India; pp. 50–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra LC. New Delhi: CSIR Publication; 1956. Glossary of Indian medicinal plants; pp. 13–131. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Council of Scientific and Industrial Research Publication; 1959. The Wealth of India; pp. 13–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srimal RC, Sharma SC, Tandon JS. Anti-inflammatory and other pharmacological effects of Hedychium spicatum (Buch-Hem) Indian J Pharmacol. 1984;16:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sravani T, Paarakh MP. Hedychium spicatum Buch. Ham.-An overview. Pharmacologyonline. 2011;2:633–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giri D, Tamta S, Pandey A. A review account on medicinal value of Hedychium spicatum Buch-Ham ex Sm: Vulnerable medicinal plant. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:2773–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaturvedi GN, Sharma BD. Clinical studies on Hedychium spicatum (Shati): An antiasthmatic drug. J Res Indian Med. 1975;10:6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahu RB. Clinical trial of Hedychium spicatum in tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. J Nepal Pharm Assoc. 1979;7:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandon SK, Chandra S, Gupta S, Lal J. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Hedychium spicatum. Indian J Pharm Sci. 1997;59:148–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armitage AK, Boswood J, Large BJ. Thioxanthines with potent bronchodilator and coronary dilator properties. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1961;16:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1961.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitra SK, Gopumadhavan S, Venkataranganna MV, Anturlikar SD. Anti-asthmatic and anti-anaphylactic effect of E-721B, a herbal formulation. Indian J Pharmacol. 1999;31:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eagleton GB, Watt J. Acute gastric ulceration in the guinea-pig induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of aqueous histamine. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1965;90:679–81. doi: 10.1002/path.1700900243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winter CA, Risely EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenin-induced edema in hind paws of the rat as an assay for anti-inflammatory drugs. Pro Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies OL, Raventos J, Walpole AL. A method for the evaluation of analgesic activity using rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1946;1:255–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam MK, Singh A, Rao CV, Goel RK. Toxicological evaluation of Murraya paniculata (L.) leaves extract on rodents. Am J Pharm Toxicol. 2012;7:62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain A, Virmani OP, Popli SP, Misra LN, Gupta MM, Srivastava GN, et al. Lucknow, India: CIMAP Publication; 1992. Dictionary of Indian medicinal plants; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marone G, Casolara V, Patella V, Florio O, Triggiani M. Molecular and cellular biology of mast cells and basophils. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;114:207–17. doi: 10.1159/000237670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder JT, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Subotka K, White JM, Lichtenstein LM. Ig Edependent IL-4 secretion by human basophils.The relationship between cytokine production and histamine release in mixed leukocyte cultures. J Immunol. 1994;153:1808–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gopumadhavan S, Rafiq M, Venkataranganna MV, Mitra SK. Antihistaminic and anti-anaphylactic activity of HK-07, a herbal formulation. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005;37:300–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Rosa M, Giroud JP, Willoughby DA. Studies of the mediators of the acute inflammatory response induced in rats in different sites by carrageenan and turpentine. J Pathol. 1971;104:15–29. doi: 10.1002/path.1711040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willams TJ, Morlay J. Prostaglandins as potentiators of increased vascular permeability in inflammation. Nature. 1973;246:215–7. doi: 10.1038/246215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White M. Mediators of inflammation and inflammatory process. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:5378–81. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg SN, Shawl AS, Gulati BC. Sesquiterpene alcohols from Hedychium spicatum var.acuminatum. Indian Perfum. 1977;21:79. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixit VK, Varma KC, Vashisht VN. Studies on Essential Oils of Rhizomes of Hedychium-Spicatum and Hedychium-Coronarium. Indian J Pharm. 1977;39:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigam MC, Siddiqui MS, Misra LN, Sen T. Gas chromatographic examination of the essential oil of rhizomes of Hedychium spicatum. Parfum Kosmet. 1976;60:245. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bottini AT, Garfagnoli DJ, Delgado LS, Dev V, Duong ST, Kelley CG. Sesquiterpene alcohol from Hedychium spicatum var.acuminatum. J Nat Prod. 1987;50:732–4. doi: 10.1021/np50052a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loizou S, Lekakis I, Chrousos GP, Moutsatou P. Beta-sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:551–8. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhalke RD, Pal SC. Anti- inflammatory and antinociceptive activity of Pterospermum acerifolium leaves. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nirmal SA, Pal SC, Mandal SC. Antiasthmatic activity of Nyctanthes arbortristis leaves. Lat Am J Pharm. 2011;30:654–60. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos FA, Rao VS. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Bunium persicum essential oil, hydroalcoholic and polyphenolic extracts in animal models. Phytother Res. 2000;14:240–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hajhashemi V, Saijadi SE, Zomorodkia M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Bunium persicum essential oil, hydroalcoholic and polyphenolic extracts in animal models. Pharm Biol. 2011;49:146–51. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2010.504966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]