Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

The objective of this project was to develop a virtual temporal bone dissection system that would provide an enhanced educational experience for the training of otologic surgeons.

Study Design

A randomized, controlled, multi-institutional single blinded validation study.

Methods

The project encompassed 4 areas of emphasis: structural data acquisition, integration of the system, dissemination of the system, and validation.

Results

Structural acquisition was performed on multiple imaging platforms. Integration achieved a cost effective system. Dissemination was achieved on different levels including casual interest, downloading of software, and full involvement in development and validation studies. A validation study was performed at 8 different training institutions across the country using a two arm, randomized trial where study subjects were randomized to a two-week practice session using either the virtual temporal bone or standard cadaveric temporal bones. Eighty subjects were enrolled and randomized to one of the two treatment arms, 65 completed the study. There was no difference between the two groups using a blinded rating tool to assess performance after training.

Conclusions

1. A virtual temporal bone dissection system has been developed and compared to cadaveric temporal bones for practice using a multi-center trial. 2. There is no statistical difference seen between practice on the current simulator when compared to practice on human cadaveric temporal bones. 3. Further refinements in structural acquisition and interface design have been identified which can be implemented prior to full incorporation into training programs and use for objective skills assessment.

Keywords: Simulation training, Temporal bone simulation, Surgical simulation, Surgical training

Introduction

Temporal bone surgery is one of the most technically demanding aspects of otolaryngology training. As such, many resources have been devoted to developing training regimens that will move the novice surgeon to that of a capable and competent operator upon graduation from an accredited residency-training program in the U.S. There is however, much variability in training methodology, technical skill and the trainee’s confidence and competence at the time of graduation. Additionally, many training programs in less developed countries suffer from marginal training in otologic surgery given little or no access to the temporal bone laboratory. Running parallel to this are the relatively recent developments in the area of surgical simulation that may hold the key to more robust and objectively driven technical skills training regimens. There has been significant progress with the use of simulation training of laparoscopic surgery with studies demonstrating its validity and efficacy (1). The objective of this design-directed research project is the development, evaluation, and dissemination of a computer-synthesized environment that emulates temporal bone dissection for training residents in otologic surgery. The scope of this project necessitated a multi-disciplinary approach that was designed, developed and executed under the direction of the primary author. The expected application of this research is to provide an adjuvant environment for learning temporal bone surgery and to improve assessment and proficiency required in formative development.

Specifically, the goal of this project was to provide a computer based fully simulated “virtual temporal bone” based on acquired image data that allowed discreet directed “dissection” of the virtual bone.

The work was divided into the following key areas:

Structural Acquisition (Imaging and histology)

Integration (data, system operations, visual representation)

Dissemination, (training, and physical system distribution)

Validation (trials at local and remote sites)

Methods

I. Structural Acquisition

Key to any simulation development is an accurate acquisition of data to form the environment. With respect to structural data acquisition, three-dimensional data must be obtained in such a way as to be efficiently rendered in three dimensions. This necessitates not only high in-plane resolution but also high out-of-plane resolution (slice thickness and distance between slices). The goal therefore of the imaging methodology is to obtain as close to an isotropic (in plane resolution = out of plane resolution) acquisition as possible. Several areas of imaging technology were explored to provide the structural data for the simulator. Acquisition of bony data was deemed most critical and was performed using several methodologies that included a standard clinical CT scanner (0.6mm resolution), and a microCT scanner (60micron) and ultra resolution CT scanner (6 micron). Scans were evaluated for ease of acquisition, feasibility of use, and adequacy of display within the simulator. MicroCT and ultraCT image data were not used in the initial simulator because of a number of issues related to processing of specimens, size of data sets and the lack of extensibility to other institutions. Ten separate cadaveric temporal bones obtained from our institution’s Body Donation Program were utilized for the project. All were considered free of pathology based on review of axial sections of the original acquisition.

In situ CT scans were acquired with a multi-detector (8 slice) CT scanner (Light Speed Ultra; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wis.). Specimens are scanned and reconstructed with the following parameters: section thickness of 0.625 mm using an axial acquisition, gantry rotation time of 1 second, x-ray tube voltage of 120 kV, x-ray tube current of 200 mA, and an imaging field of view of 10 cm. The imaging protocol yields 0.625 mm thick axial images of the temporal bone with a 512 × 512 image matrix. Volume resolution will therefore be 0.19 × 0.19 × 0.625 mm. These scans served as the basis for the simulator system that was disseminated for the multi-institutional study.

Following in situ imaging, bilateral excisions of the temporal bones were performed and the specimens were trimmed to contain the middle ear laterally, and the otic capsule and internal acoustic canal medially. MicroCT images of the excised temporal bone were obtained using a dedicated microradiography system consisting of a microfocal x-ray source (Phoenix X/ray, Wunstorf Germany) a 7-axis micro-positioning system and a high resolution X-ray image intensifier coupled to a scientific CCD camera (Thomson Tubes Electroniques, Cedex France). In order to safely expose the specimens to air, a 70% ethanol solution is used to exchange the formalin initially used to fix the specimens. One hundred and eighty 512 × 512 12-bit projection radiographs are collected in a circle at 1degree intervals around the specimen. The projection radiographs are acquired at 40 kV and 200 microA with the image intensifier operating in 7-inch mode. The images are background corrected; the gray level intensities are scaled relative to that of air. A 512 × 512 × 512 volume is reconstructed using a modified Feldkamp con cone-beam reconstruction algorithm (2).

Use of Histologic Data

One of the early goals of this work was to investigate the potential for using histologic image data as the basis for the simulation. The rationale behind this was that if it could be shown that histologic data could be used for the simulation, the image data acquired from the numerous specimens of the National Temporal Bone Registry could be leveraged to provide an extensive collection of virtual temporal bones with unique pathology. In order to attempt to integrate historical data temporal bone data, several experiments were undertaken to reconstruct histologic data obtained from 2 different institutions. Several problems arose when trying to use standard temporal bone histology slides for data. The standard histologic process for most temporal bone sectioning is to mount and preserve every 5th to 10th section at 10micron thickness. These are then individually stained. When these sectioned are stacked in sequence, a three-dimensional volume is achieved.

II. Integration

One of the key components of this project was to refine a rendering algorithm that provided realistic visual and haptic (providing sense of touch or feel) display while maintaining the interactivity required for surgical manipulation (frame rates 20 to 30fps) that was realistic. Unique to the particular approach taken was the development of a “volume based” rendering algorithm for visual and haptic display. Direct volume rendering eliminates the expensive pre-processing needed for indirect methods, maintains underlying complexity, and provides an avenue to exploit patient-specific data. This is in contrast with the more common “surface based” rendering employed in typical video gaming systems. Surface based rendering provides very accurate “surfaces” which are great for fly-through application and maize like navigation. This technique breaks down when interaction with structures is required such as accurate removal or cutting of the actual data. Surface based rendering is akin to painting on eggshells where if one wishes to interact beyond the surface, there is no deeper data. Three-dimensional data is digitally processed to extract surfaces of volumes that are then displayed, ignoring the deeper structure of the volume. Volume based rendering continually processes the entire three-dimensional volume and updates every data point within the three dimensional volume with any interaction. This becomes important when one wishes to cut into the three dimensional volume in real time (30 frames per second). The methods for rendering were refined to provide a more realistic representation by adding complex lighting and shading models. Additionally, the rendering algorithm was converted to OpenGL, a rendering language that allowed for continued development using more modern tools and the ability to take advantage of new graphics cards available in “off-the-shelf” PCs. This migration to OpenGL was key to providing a relatively inexpensive platform that could be duplicated and disseminated at a reasonable cost. Because of this early prototype a number of progressive otolaryngology departments volunteered without compensation to participate in the further development and eventual testing of the system (See Table 1).

Table I.

Participating Institution

| Institutions | Subjects Completing Study |

|---|---|

| Duke University | 10 |

| Eastern Virginia University | 4 |

| Henry Ford Health System | 7 |

| University of Iowa | 13 |

| Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary | 10 |

| University of Mississippi | 6 |

| University of Texas, Southwestern | 8 |

| Virginia Commonwealth University | 8 |

III. Dissemination

Written invitations were disseminated to the program directors of all residency-training programs in the U. S. requesting participation in development and a multi-institutional evaluation of the system. A website was established to expedite communication (www.osc.edu/vtbone) to participating institutions and to capture demographic data about each potential participant. Investigator meetings were held during American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, Inc. annual meetings to introduce the system and provide additional detail regarding the multi-institutional study. A local study coordinator was appointed at each site to provide expert feedback as well as coordinate study activity. In order to demonstrate the system and present the study the senior author performed visits to each testing site.

IV. Validation

IRB Approval

This study was conducted under both Institutional Review Board approval at the home institution as well as site-specific IRB approval. A comprehensive data safety and monitoring plan was developed and monitored by an independent data safety committee at the home institution. This was implemented at the request of NIDCD.

A. Study Design

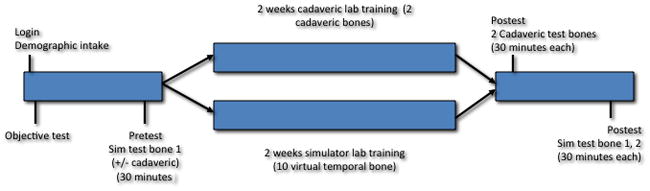

A single blinded randomized controlled trial was designed to compare the effect of temporal bone dissection practice in the simulator to that in a temporal bone dissection laboratory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of validation study design

Study sites/study population

The study population was composed of residents and medical students in ACGME approved Otolaryngology training programs within the United States. IRB approved consent was obtained from each study subject without site coordinator coercion and participants were allowed to drop out of the study at any time. Eighty subjects were recruited from 8 different institutions across the United States (See Table 1). Sixty-five were able to complete the study. Each participating institution had a local study coordinator (member of the faculty of that particular institution). The site coordinator was responsible for recruitment of subjects, assignment of subjects to individual study arms, assurance of study protocol execution, system maintenance and data collection. Sites were recruited based on interest in temporal bone simulation and willingness to conduct the study locally without remuneration.

Once a site was identified, arrangements were made for the lead investigator to visit the site. A full system as described above was ground shipped to the participating site and a short presentation was given to potential study subjects outlining the rationale for simulation technology in surgical training, a history of project development, a study overview, IRB considerations, followed by a short instructional demonstration of the system. A printed manual on the operation of the system and instructions for the study was provided. Additionally, a web address to download a pdf version of the instruction manual was provided to allow convenient access. Upon completion of this phase, the lead investigator would review the protocol with the site coordinator, review IRB concerns and demonstrate the randomization software to be used in assigning study subjects to individual treatment arms.

Subject randomization

The total number of study subjects was determined for a specific site and the date of the post training testing was established. The site coordinator then entered the number of subjects into an application specifically designed to provide random usernames consisting of a 6-character string utilizing a combination of 3 letters and 3 numbers. Level of training was entered for each subject ranging from M1-R5 (M referring to medical students, R referring to resident and numerical characters representing year of training). The application then automatically randomized subjects with priority given to assign equal number of subjects from each year of training within each of the two treatment arms (see Figure 1). This application then automatically set up the simulator for the study by registering user names for the different practice arms so that individuals in the cadaveric arm would not have access to the simulator until it was time to perform post training testing. The use of random user names provided assurance that performance outcomes and specific individual identities could be decoupled. This allayed IRB concerns of potential injury to reputation should poor performance become discovered.

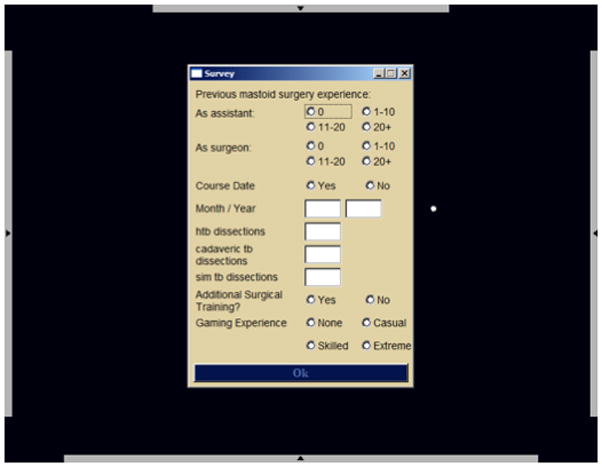

Demographic capture and pre practice performance assessment

Study subjects signed into the system with their assigned random user names. They were then asked a series of demographic questions (Figure 2). The purpose of capturing this demographic information was to control for variables that might potentially affect outcomes such as temporal bone dissection experience and gaming experience. The next screen presented an “objective test” consisting of a skills test designed to measure innate skill within the simulation. This test presented the subject with a white sphere with a green pyramid affixed to the surface. Individuals were instructed to drill away the pyramid using the virtual drill and avoid penetrating the white surface under which a red area was located. Subjects were allowed 15 minutes to perform this task. Both the process by which the individual performed the task as well as the final product was recorded by the system. The purpose of this element was to obtain some measure of dexterity with the interface. All study subjects were then presented with a virtual temporal bone and asked to perform as much of a complete mastoidectomy with facial recess approach as they could accomplish in a 30-minute time frame. All study subjects dissected the same pre practice virtual bone. A timer was presented in the left upper corner of the visual field. Several institutions had access to additional cadaveric temporal bones and were able to perform pre practice cadaveric temporal bone dissections in addition to virtual bone dissections as a measure of pre training skill.

Figure 2.

Demographic capture screen.

Practice period

Two weeks of practice with either cadaveric specimens or the simulator was allowed. Those study subjects that were randomized to traditional training were instructed to practice a complete mastoidectomy with facial recess approach on 2 cadaveric temporal bones. These individuals were locked out of the system until the 2 weeks allotted for practice ended. After the practice time had expired, these subjects were instructed to log back into the system for post training testing. Those study subjects that were assigned to simulator training were instructed to continue practicing using the simulator during the 2-week practice session. A total of 8 different virtual bones were made available during the training period for these subjects. A paper log of practice time was maintained by those randomized to cadaveric practice, the simulator system was programmed to capture practice time on those randomized to simulation practice.

Post practice testing

After completion of the 2-week training period, all study subjects were instructed to log back into the system to perform the same pre practice task (complete mastoidectomy with facial recess approach) with the same time limits on two virtual temporal bones. This was performed on the same pre practice virtual bone and another randomly chosen virtual bone. They were also instructed to perform the same task under the same time constraints on 2 cadaveric bones.

B. Performance assessment

The WS1 rating scale

In order to measure temporal bone dissection performance, a tool to evaluate technical skill was developed which consisted of a 35 item binary scale. This instrument was adapted from a local expert’s own tool developed for final product assessment of resident temporal bone dissections. This scale was modified and underwent a local validation study which showed good inter and intra rater reliability as well as construct validity for temporal bone dissection performance (3,4). This instrument was used to rate each dissected cadaveric bone (See Appendix IIB).

Blinded rating

Test cadaveric bones were labeled and each site coordinator maintained a spreadsheet that linked specific pre and post training bones to specific usernames. All bones were individually scored using the WS1 by two experienced otologists who were blinded to study subject, whether the bone was pre or post training and treatment arm. Pre and post training dissected virtual bones were recorded within the simulator.

C. Statistical methods

The main outcome variable (test score) was skewed and therefore log transformed to achieve normality. Mixed linear models were used to study the group differences while adjusting for potential confounders (such as residency level, objective test scores, institution and the number of previous human temporal bone dissections). The variables treated as random effects were study subject, grader, bone nested within study subject, and grader by bone interaction nested within study subject. Linear models (ANOVA) were used to study the differences in hours of time logged between the groups and by institutions. Nesting was performed to account for the variability inherent in each cadaveric bone. Bones cannot be treated as the same across study subjects as they were indeed different. The model needs to account for this variability and this was accomplished by including these factors as random in the model.

Results

I. Structural Acquisition

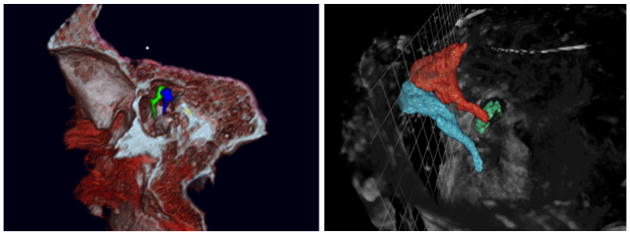

As mentioned in the methods section, we explored various imaging modalities for the project. These included standard clinical CT scanner (0.6mm resolution), and a microCT scanner (60micron) and ultra resolution CT scanner (6 micron). Figure 3 shows a frame capture from a rendered clinical scan temporal bone as it was integrated into the simulator as well as a rendered image from the microCT scan data demonstrating the excellent resolution of the ossicles.

Figure 3.

Left: Clinical CTscan (screen shot from simulator). Right: MicroCT: Relationships of ossicles are highlighted.

With respect to the histologic data we obtained, the standard histologic acquisition is not conducive to three-dimensional reconstruction. First, since there is a considerable amount of data missing between sections and the in plane resolution of the slides is several orders of magnitude larger than the out-of-plane resolution (non isotropic) there are huge gaps in the data and perfect alignment can not be achieved. Secondly, although staining was most likely performed simultaneously, variability existed in intensities of various structures between mounted sections; this adds variability to the visualization of individual structures. Lastly, mounting was not performed uniformly and sections were located on individual slide with somewhat random orientations. These issues made it a significant challenge to create a useful three-dimensional volume from the data. Two data sets were obtained which captured every section at 10micron thickness (one from The House Ear Institute and one from the Massachusetts Eye and Ear infirmary). Although every section was available, the other issues of staining and orientation made the data sets unfavorable in our hands for volume display (5,6).

II. Integration

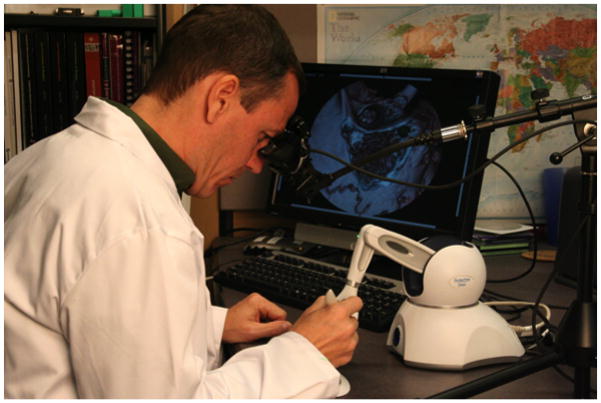

The simulation environment (Figure 4) provides representations of temporal bones through the use of reconstructed computed tomography (CT) of cadaveric specimens. Various aspects of the microscope are available, including zooming and panning. Common manipulations during virtual dissection include controlling the magnification level and moving the microscope in the image plane. Additional functions allow for arbitrary orientation of the virtual specimen. A drill is emulated using a hand-held force-feedback (haptic) device. A PHANTOM® OMNI haptic device from SensAble Technologies, Inc. is used for this purpose. The OMNI devices provide 6 Degrees of Freedom (DOF) for position tracking and 3 DOF of force. We calculate forces directly on the volumetric data generated from the CT scan. Closely associated with the amount of force presented on the drill, we modulate sampled sounds recorded during an actual temporal bone dissection. Pitch modulations allows correlation of the amount of pressure being placed on the drill, as well providing an auditory signal as to the amount of resistance of the bone being drilled at that time.

Figure 4.

Temporal Bone Dissection Simulator as used in multi-institutional study

The system was designed to run on commodity based or “off the shelf” hardware so that the system would be affordable, allowing broader dissemination of the technology. The system runs on a MS Windows ® operating system (both XP and VISTA). The current hardware consists of a HP xw4600 Workstation, using an Intel Core 2 Duo 2.66GHz, 4 MB, 1333 MHz FEB with 4Gb DDR-800 ECC RAM and NVIDIA Quadro FX4600 768 PCIe video card (http://www.hp.com, http://www.nVIDIA.com). The interface includes a standard keyboard and mouse, PHANTOMR Omni device for haptic feedback (SensAble Technologies, Inc. Woburn, MA), and z800 binocular display device from eMagin (http://www.3dvisor.com/) or the Headplay personal cinema system (http://www.headplay.com) in addition to the standard HP monitor. Further details and alternate hardware configurations can be seen at: http://www.osc.edu/research/Biomed/vtbone/hardware/index.htm

The user looks through the binocular display or at the computer monitor and holds the 3D Omni joystick. The joystick is used to make selections from menus as well as for drilling. The sound of the drill is played through stereo speakers. A “tutor” subsystem is employed and activated through a menu selection. This presents selective structures in the dataset to aid the user in locating these structures and learn relationships of these structures in a particular region.

III. Dissemination

The virtual temporal bone dissection simulator was disseminated in multiple ways. First, presentation at the American Academy of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, Inc. Annual meeting in 2001 was the first time the system was available to the public. There was significant interest both from national as well as international individuals. As a result of this exposure, a working group of interested individuals and their associated institutions was assembled and met on an annual basis at subsequent meetings. Originally, there were 36 different institutions with 6 from outside the U.S. who participated in discussions and/or expressed interest in becoming associated with the project. A website was established to disseminate additional information regarding the project with the ability to download the original research proposal, IRB documents and data collection interface to collect data regarding a particular institution’s demographics. Eight institutions were able to fully commit to performing the multi-center trial (Table I, Appendix II).

IV. Validation

Eighty study subjects were enrolled from 8 different institutions across the U.S. and demographic data were collected. Each of these 80 subjects performed the pre training virtual temporal bone dissection and 31 were able to perform pre training cadaveric dissections. Of these 80, 65 completed the entire testing protocol with 32 in the simulator group and 33 in the traditional training group. The distribution of level of experience was similar (statistically not significant) in the two groups (Table 2, Appendix II). The two groups were similar in terms of number having a previous temporal bone course, previous operative experience as either a surgeon or assistant, or previous gaming experience (Tables 3–8, Appendix II). The variability of objective test (drilling the pyramid off of the sphere) scores did not show a significant association with any of the demographic variables such as year of training, temporal bone dissection experience, gaming experience, or WS1 score post practice.

Table II.

Tests of Fixed Effects for all study subjects

| Table IIa: Tests of Fixed Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Num D.F | Den D.F | F Value | P-value |

| Group | 1 | 40.7 | 0.35 | 0.5598 |

| Level | 5 | 39.3 | 1.06 | 0.3968 |

| Objective Score | 1 | 38.7 | 0.38 | 0.5412 |

| Number of Previous Dissections | 1 | 40.3 | 0.19 | 0.6632 |

| Institution | 7 | 40.2 | 3.50 | 0.0051 |

| Table IIb: Least Square Means | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Estimate | Standard Error | Lower 95% CL | Upper 95% CL |

| Simulator | 2.1977 | 0.09613 | 1.9969 | 2.3986 |

| Traditional | 2.1383 | 0.09690 | 1.9361 | 2.3406 |

| Table IIc: Difference of Least Square Means | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard Error | Lower 95% CL | Upper 95% CL | P-value | |

| Sim – Trad | 0.0594 | 0.1010 | −0.1446 | 0.2634 | 0.5598 |

Table III.

Tests of Fixed Effects for subjects completing both pre and post training cadaveric dissections.

| Table IIIa: Tests for Fixed Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Num DF | Den DF | F Value | P-value |

| Group | 1 | 28.7 | 0.00 | 0.9949 |

| Test | 1 | 55.9 | 3.78 | 0.0569 |

| Group*Test | 1 | 55.9 | 3.70 | 0.0594 |

| Institution | 2 | 27 | 5.12 | 0.0130 |

| Table IIIb: Model Based Least Square Estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Test | Estimate | Std. Error |

| Sim | Post | 9.3372 | 1.1913 |

| Sim | Pre | 9.3256 | 1.3000 |

| Traditional | Post | 10.4873 | 1.1001 |

| Traditional | Pre | 8.1905 | 1.1839 |

A. Tests of Fixed Effects using a mixed model adjusted for institution for all study subjects

Analysis

The model was adjusted for residency level, objective test scores, the number of previous human temporal bone dissections, and institution as fixed effects. Student, grader, bone nested within student, and grader by bone interaction nested within student were included as random effects.

Modeling Results

Table IIa: Tests of Fixed Effects

Table IIb: Least Square Means

Table IIc: Difference of Least Square Means

Interpretation of Results

There were not significant differences between the two test groups after adjusting for the above-mentioned variables. The difference between the two groups on the natural log scale was 0.0594 which corresponds to exp(0.0594) = 1.06 on the original test scale (p-value = 0.5598). Institution was significant in the model (p-value = 0.0051). This indicates that the mean test grade for students in at least one institution was significantly different from the others.

B. Tests of Fixed Effects using a mixed model for subjects completing both pre and post training cadaveric dissections

Of the 31 study subjects that were able to perform cadaveric dissections before training, pre and post training scores were essentially the same (~9.3) for the simulator group. For the Traditional group, Pre training scores (8.2) were significantly lower than post training scores (10.5). The Traditional group showed more improvement than the simulation group but this was not statistically significant.

Analysis

A mixed model (a model that includes “fixed” and “random” effects) was run with test score as the outcome variable. The independent variables were group, test (pre or post), an interaction term between group and test, and institution. The interaction term between group and test is used to study “behaviors” of the 2 groups and is different depending on the test (pre or post). An example would be that one group could do better on the pre test than the post-test. This type of relationship would be identified by the interaction term that in this case was not significant. The variables treated as random for this model were subject, grader, bone, and a grader by bone interaction term.

Modeling Results

Table IIIa: Tests of Fixed Effects

Table IIIb: Least Square Means

Interpretation of results

There is a significant difference in test scores between institutions (p-value = 0.0130). The Group*Test interaction is approaching significance indicating that the difference in pretest to post test scores was slightly higher for the traditional group than the simulator group (p-value = 0.0594). The difference between the simulator pre and traditional pre is not significant.

Discussion

I. Structural Acquisition

The surgical procedure that we chose to support was the complete mastoidectomy with facial recess approach as defined by Nelson (7). In this approach, the vast majority of dissection includes identification and preservation of landmarks without violation of soft tissue structure. Because of the overwhelming emphasis on bony structure, our primary focus was to emphasize acquisition of bony data. We explored data from various sources as mentioned in several of the above sections but settled on clinical resolution CT data as it was easily obtainable, provided a protocol that was extensible to other facilities for additional specimen acquisition, resulted in data sizes that were manageable within the simulator, and provided what we perceived to be adequate resolution.

Resolution was adequate for early and more basic maneuvers such as identification of surface anatomy, identification of major landmarks such as the tegmen, sigmoid sinus, posterior canal wall and horizontal canal. Identification of the facial nerve although easily seen in the “tutor application” was difficult to distinguish when actually drilling. This may have been do to the fact that the nerve was identified and segmented based on the tagging of voxels surrounding the facial canal as opposed to the actual soft tissue of the nerve itself. Continued work is being done to better identify the facial canal in higher resolution as well as use of micro MRI to resolve structural data of the nerve itself.

Use of higher resolution data is a double-edged sword. Additional detail can be provided to identify fine structures as one does under the operating microscope when changing objectives. Dealing with higher resolution data sets also puts additional demands on the computational aspects of the simulation in that a greater amount of data needs to be processed in real time to provide adequate interaction.

Use of UltraCT data provides incredible detail yet still remains problematic because of the size of the files. One temporal bone scan contains up to 40GB of data requiring up to 500GB of disc space to be adequately integrated into a rendering program. Future systems will likely incorporate these larger data sets with finer anatomical detail as the cost of processing ever-greater amounts of data comes down. This higher resolution CT data have not been incorporated into the current system. Processing this data remains an area of active research. Comparatively speaking, this data is 1000 times the size of current data sets used in the simulator system. Despite these large sizes, speed of processing could possibly be maintained by using a hierarchical data format. In this format, low-resolution data can be used when lower resolution is adequate to depict sufficient detail such as in decorticating the mastoid, and skeletonizing larger structures such as the tegmen, sigmoid and the posterior canal wall. Higher resolution data can be utilized when there is demand it, such as identifying the facial nerve and middle ear work. Using hierarchical data requires that the data sets be merged and integrated into one data set with variance in resolution using a hierarchical tree.

We found that the integration of multiple data sets is quite a wonderfully challenging problem. One data set, usually the lower resolution, is designated as a rigid framework while other, higher resolution or alternate modality data set is scaled and oriented to match the first. This process was found to require both human interactions for course orientation (within 30 degrees) as well as gross scaling. A difference calculation is performed on the 2 data sets in their current orientation and a modification to that orientation is done that decreases the difference. The difference calculation we used takes advantage of statistical dependence in both data sets and is known as “Mutual Information.” This has been demonstrated in the past with two-dimensional data but had not been previously done with three-dimensional data of different scales (8). In order to provide the resolution necessary to support more complex and fine work such as middle ear work and facial nerve identification and skeletonization further research must be pursued to solve the process of data merging using multi-scale and multi-modal data.

With respect to histologic data, recommendations were made regarding future acquisition of temporal bone structural data obtained through the National Temporal Bone Consortium that might lead to development of a potential National Temporal Bone digital structural data bank that could be accessed and utilized by temporal bone dissection simulators such as that described in this work.

The ability to develop a repeatable and extensible process to capture structural data at a high enough resolution and format that can be used by a temporal bone simulator is paramount to the development of large collections of digital bones that support exposure to the anatomical variation seen in clinical practice. Such a collection leverages one of the most significant aspects of simulation training; that trainees can repeatedly practice without destruction of specimens. The exposure the trainee has to anatomical variation and different pathologies becomes essentially limitless as specimens can be added, stored and reused from an online digital temporal bone bank.

Sorensen et al. who have developed a temporal bone simulator based on serial cryosections of a single specimen have demonstrated alternate methodologies of data acquisition. This process produced a data set with an impressive resolution of 3,056 × 2,032 pixels per section × 605 sections (9). As impressive as this process is, it is extremely labor intensive and does not lend itself to reproduction outside of the original laboratory. This impacts the ability to add additional specimens at any significant rate.

II. Integration

A. Imaging Resolution/modality

Resolution of data was one of the most common issues identified by users of the system as being problematic. Certain basic maneuvers such as decorticating the mastoid, skeletonzing the sigmoid sinus were easily performed. Identification of the facial nerve and in particular the corda tympani were especially problematic. Even though there is provision for “increasing the magnification” this provided only a zoom feature that spread the available volume elements further apart without increasing resolution as one would with increasing the power of magnification on the operating microscope. We have looked into integrating higher resolution data sets that are produced by research imaging systems and using a hierarchical data system whereby lower resolution data is used for certain aspects of the procedure and higher resolution data would be “swapped in” when needed.

Secondly, because the temporal bone data was obtained with CT scanning, soft tissue representation was limited. In order to provide adequate sharp detail of bone and clarity of image, bone window intensity values were used in order to process the data. This essentially eliminated any significant soft tissue representation and structures such as the tegmen were not resolved well. Additionally, some areas of thin bone such as the tegmen and fine trabeculae may have been averaged out of the final volume data file. This made such maneuvers as thinning the tegmen without violation very challenging.

B. Stereovision

Paramount to adequate dissection is the need for stereovision. Depth perception is poor without stereovision. The original design incorporated stereoscopic visualization through a pair of virtual binoculars but these were cost prohibitive for dissemination. Lower cost goggles were then incorporated and based on manufacturers specifications of both the goggles and the graphics board should work well. Despite extensive research into the area, a cost effective and functional platform was not identified at the time of the study. Limited depth perception cues were provided in the lighting model which cast a shadowing effect and form from motion when the bone was rotated also provided some semblance of depth perception. This however was not ideal and proved to be an additional limitation. Subsequent development by the graphics board companies has produced more robust and cost effective stereo solutions that are now integrated into the system.

IV. Dissemination

Initially, dissemination was labor intensive but as momentum built, the enthusiasm for temporal bone surgical simulation drove further exposure. Word of mouth and Internet search engines continued to disseminate knowledge of the project and the goals associated with the work. There continues to be strong and broad interest in the work with queries regarding software downloads and hardware configurations as well as requests for participation in the work. This geometrically expanding interest is testimony to the interest and perceived need for such systems to be rigorously developed and disseminated. Additional projects that require dissemination and participation across a broad base of participants include:

A. Digital temporal bone bank

Development of a digital temporal bone bank that can be accessed online by any student anywhere in the world would require participation by multiple individuals with the capability to capture image data on unique temporal bone specimens. This “virtual temporal bone bank” could have tremendous impact in the US and other developed countries. There is considerable impact to developing countries that do not have access to cadaveric specimens and very limited clinical material for learning.

B. Metric Development and Standardization of curriculum

The development of standardized metrics to guide curriculum development and assessment is necessary for a high level of uniform training to be achieved. This can only be done through a consortium of institutions and experts. The establishment of a core group of dedicated individuals and institutions has been achieved and has expressed interest in continuing to be involved in future projects currently under funding review. These sites will provide not only the broad expert input needed to move to a fully functional simulator training system but also provide a clinical testing ground for iterative development.

C. Objective standardized technical skills assessment

Closely coupled with metrics and curriculum development is the task of technical skills assessment. Objective technical skills assessment can be performed in a uniform and objective fashion providing a source of data to assess training paradigms and individual trainees for both certification and maintenance of technical skill. This too can only be accomplished through an established core of institutions willing to continue to provide input and refinement to the virtual training system.

The dissemination of this project provides the foundation for further development and refinement with the goal of improving not only training methodology for temporal bone surgery but also objective technical skills assessment.

IV. Validation

The objective of this study was the development and dissemination of a virtual temporal bone dissection system. Even though, the validation of this system was not the primary goal, the data presented in this work represent one of the largest, randomized controlled trials looking at the effect of simulator training for surgical skills in Otolaryngology. Simulator training has been shown to be effective in sinus surgery (10) but few studies have been done with the available temporal bone dissection simulators (see Other temporal bone simulators below).

This study did not show any differences between the post training performances (based on WS1) after 2 weeks of practice using the simulator or the cadaveric laboratory. This would indicate that simulator practice is not inferior to cadaveric practice. Also, it does not show a negative effect of training in this particular simulator. Below is presented a discussion on factors influencing the validation study as well as implications for further development.

A. Factors influencing study design

1. Cadaveric bones

In planning for this study, the single most limiting factor that arose was the availability of cadaveric bones. This issue not only dramatically influenced the study design but also had a direct impact on the ability of institutions to participate. Direct observation of temporal bone dissection in live patients with real-time assessment of performance by expert raters using a validated instrument would be problematic to employ on any large scale. We therefore felt that end product analysis of cadaveric temporal bone dissection would be the closest method of assessment that would meet the criteria for feasible blinded assessment. Ideally, obtaining both pre practice and post practice assessment using human temporal bones should be used. Our projected subject enrollment was 100 study subjects. Ideally, we would have 2 measures of performance both before and after practice. Additionally, the temporal bone lab treatment arm required bones to practice. If only 2 bones were used for practice, a total of 500 cadaveric temporal bones would need to be accumulated (400 for assessment and 100 for practice). In most instances, participating institutions had limited access to bones and the decision was made to limit the number of bones used in order to recruit an adequate number of sites. After consultation with the study statistician and participating sites, it was decided to use virtual bones (data still under analysis) and the objective test as a measure of pre practice dissection skills. Two cadaveric bones per study subject involved in traditional lab practice and 2 bones per study subject for post training assessment appeared to be reasonable. A number of institutions were not able to participate even with this reduced required number of bones per site or had to limit the number of study subjects that could be enrolled at their site.

2. Grading of bones

Two experienced neurotologists used the WS1 to rate the dissected bones. This instrument is based on the final product assessment and does not take into account any aspect of the performance process (i.e. Fluidity of movement, dangerous or reckless maneuvers). A discussion regarding the validity of this method of assessment is beyond the scope of this report but suffice it to say that a combination of both may or may not have some advantage but again presents feasibility issues for a large-scale study. The rating process required more than 27 man-hours to grade all 163 bones. This proved to be a considerable time investment for two very busy academic clinicians. Available applications of any current metrics or assessment tools are time consuming and subject to bias when a human rater is involved. Development of objective assessment measures within a simulator may provide efficient and objective assessments.

B. Factors influencing outcome

1. Study subject motivation/time commitment

One of the most significant concerns regarding technical skills performance on this project as well as the issues of attainment and practice of technical skills is in the motivation of the individual. In the confines of this project, this was one variable that could not be easily controlled. Study subjects were busy otolaryngology residents and as such have very little spare time to devote to tasks that do not directly impact their “grade” or provide compensation. IRB regulation did not permit “coercion” to participate, perform at a high level or even complete the study once enrolled. This could have easily impacted both time used to practice in the various treatment arms as well as technical performance on the post training dissections. This heterogeneity in motivation could account for a significant portion of the variability in the results in that we were not able to even demonstrate construct validity with the WS1 in that performance did not correlate with level of training. Motivation has been shown to be critically important in simulation training in general and can dramatically effect outcomes (11). Factors that affect motivation include: perception that it is important to the subject’s daily work and the trainee’s perceptions of their own skill. In order for a more effective simulation training mechanism to mature, this must be taken into account and addressed with potential study subjects prior to enrollment in future efficacy studies. Motivation can be improved by offering reward for improved performance and has also been shown to improve when encouraged by supervisors and when more detailed information regarding the necessity of training is provided. Others have suggested that the “coolness factor” (11) can also provide motivation for trainees involved in surgical simulation environments. We chose monetary reward and “coolness factors” only to avoid any suggestion of coercion. Perhaps providing a more detailed discussion with study subjects about the importance of temporal bone simulation training and providing a pre training assessment of skill could provide additional motivation without coercion from faculty.

2. Performance measurements

The WS1 has been shown in a trial of a limited number of subjects to demonstrate both inter and intra rater reliability as well as a tendency toward constructs validity (5). The instrument was used on a study population that was familiar with the assessment criteria. Specifically, they were trained by the developer of the original metrics and may have been “trained to the test.” When this tool was used to judge a wider and more heterogeneous population, its validity and reliability to measure technical skills performance may have become limited.

The fact that construct validity was not demonstrated when the WS1 was utilized to rate performance on this much larger study would imply that it was not a valid measure of performance for this particular task. This may be explained by the study subjects not being clear on the task to be measured or that they all simply did not try to perform the task to the best of their ability. Additionally there may have been such variation in training that only those individuals that were trained under the influence of the WS1 knew what to focus on.

This very point speaks to the need for universally agreed upon metrics to not only develop standardized curriculum but also standardized objective measures of technical skills performance. Performance measurement and feedback must be highly coupled for adequate training to occur (11). As our system design was simply to replicate a virtual temporal bone it did not provide any feedback during training or testing. Performance testing was measured by the WS1 which is as noted above an end product assessment used at the home institution. Specific details of this performance measure were not provided to study subjects but simply the instructions to perform a complete mastoidectomy with facial recess approach. As expert raters began rating bones, it became apparent that the instrument used to rate performance was not necessarily well suited to evaluate this particular task. As such, overall scores were quite low using this instrument. The original intent of the WS1 was to evaluate a fully dissected cadaveric temporal bone with specific tasks expected to demonstrate knowledge of anatomy such as exposing landmarks that were not necessarily part of the task asked of the participants as described in Nelson’s textbook (7). In the future, development of more specific metrics for the particular task at hand will not only help to more accurately measure performance but also provide substance for curriculum development and a full-scale training simulator.

3. Significance of training institution

Training institution was the only variable that had a significant effect on the test scores. This effect was significant, regardless of practice arm (simulation or traditional). The fact that training institution accounted for most of the variability in overall WS1 scores, raises the issue of a lack of standardized training for temporal bone surgery in the US and the variability of training efficacy between institutions. Many factors are in play when one analyzes efficacy of training programs. These include time demands on trainees, the quality of faculty, facilities and trainees, and surgical experience. Having a standardized, metrics driven, simulator based training program that could be disseminated across the country could resolve some of the variability in training across the country and hopefully, if well done, elevate the overall technical skill level of otologic surgery in residency training. Additionally, as more virtual bones are added to the collection, increase in experience with more anatomic variability and pathology may even the playing field with those programs with more limited exposure.

Variability in training certainly can be demonstrated by the lack of universally defined and accepted metrics for technical skills performance for temporal bone dissection. Several groups, including our own have labored to develop and publish metrics on temporal bone dissection in the hopes of disseminating this across the country (12–16). A recent publication used various metrics from the literature to define a “master list” of temporal bone dissection metrics. This list was then subject to expert opinion via an online survey of both the American Neurotology Society and American Otological Society members with instructions to rate the importance of each criterion (15). A significant response rate was captured further indicating the need, the desire and the significance of such work on metric development. This work listed 23 metrics that were agreed upon by at least 70% of those responding to the survey as either “very important” or “important” in temporal bone surgery. The metrics were then classified into five categories such as violation of, proximity to, identification of structures as well as technique, and contextual (performing the right maneuver at the right time). The plan being that automated processing could be achieved through algorithm development to objectively, accurately and efficiently provide technical skills performance data. Plans are underway to implement this next phase of the simulator.

D. Cadaveric temporal bone training simulator vs. virtual dissection

In order for simulators to be effective, they must contain several elements that include feedback, repetitive practice, increasing levels of difficulty, ability to adapt to different learning strategies, and provision for clearly stated benchmarks and outcome measurement (11). Our system provides only the ability for repetitive practice as it was designed initially as a virtual temporal bone that could be dissected similar to the cadaveric bone. Performing a validation study of the effectiveness of this in training may have been a bit premature as simple practice without expert feedback and instruction within the confines of an effective curriculum is not sufficient to yield improvement in technical ability in the learning stages. With this in mind, the investigators of this project now hope to take the next step in development of this system into a full fledged simulator for training, integrating the elements noted above.

E. Other Temporal Bone Simulators

The VOXEL-MAN TempoSurg simulator (www.uke.de/voxel-man) is currently the only commercial temporal bone simulator in the market. This system uses 3D petrous bone models derived from high-resolution CT images and the same haptic device as our system. In contrast to our system, images are displayed stereoscopically through a mirror and projected to the desktop in front of the user. A validation study involving 20 otolaryngology physicians of varying seniority has been reported (17). Study subjects completed a self-evaluation of skill level and subsequently performed a mastoidectomy on the simulator. Two blinded raters reviewed video recordings of performance and provided an overall impression score and a score for specific domains (i.e. flow of operation, respect for tissues). A positive correlation between participants’ self-ratings of skill level and scores given by the consultants was demonstrated. An earlier validation study involving otolaryngology surgeons at the University of Toronto yielded more ambiguous findings (16). Videos were recorded of hand movements of novice and experienced surgeons performing dissection on the simulator or on a cadaveric temporal bone. Expert raters were able to discriminate novice from experienced trainees at a significant level only on cadaveric bones. There was also a trend toward discrimination in the simulator recordings, though this correlation was not significant.

The Integrated Environment for the Rehearsal and Planning of Surgical Intervention (IERAPSI) Project is another system that was developed by a consortium of European Union physicians and technologists. This group produced a temporal bone simulator that used stereoscopically rendered temporal bones derived from CT images and a more expensive haptic feedback device. The goals of this project were: 1) pre-operation planning using patient-specific data, 2) surgical simulation, and 3) education and training (18,19). The simulator functionalities were divided into “fast” and “slow” subsystems, each responsible for different tasks. Agus et al. utilized this dichotomy to decouple the simulation on a multiprocessor PC platform (20). In another report, a single expert performing a canal wall-up mastoidectomy on the simulator evaluated the system. The expert noted strong three-dimensional simulation and dust and color representation during initial stages of the procedure (decortication of the mastoid), but poor simulation when deeper structures were encountered (21).

A temporal bone simulation system developed at Stanford University utilizes CT data with a hybrid volume and surface-based rendering approach, as well as a similar haptic interface providing force feedback. Unique to their system, the haptic interface is networked, allowing a trainee to “feel” forces and maneuvers being applied by an expert in a linked system (22). Construct validity has been demonstrated by showing significantly different global scores received by experienced users compared to novice users performing a mastoidectomy on the simulator (14). Sewell et al. (23) recently presented specific metrics integrated into the simulator. Implementation of these metrics allows the simulator to provide automated instructional feedback to the user. Integrated metrics include drilling and suctioning techniques, bone removal, facial nerve exposure, and drill forces and velocities. This particular system demonstrates an excellent overall design offering integrated metrics and constant feedback to the user. It offers only one temporal bone and is currently available only at Stanford University.

Lastly, O’Leary et al. (24) have developed their own temporal bone simulation system and have used it to assess how well novice surgeons, trained on their simulator, identified real temporal bone anatomy and performed dissection of a human temporal bone. Their system makes use of a generic VR workstation, the “haptic workbench” adapted for temporal bone surgery. This system utilizes 2 more elaborate haptic devices to represent the drill and suction-irrigator. Structural data was obtained from CT scans. This system also provides network connectivity between multiple systems so that trainers can be immersed simultaneously with trainees. A non-randomized, non-controlled, non-blinded study used 12 trainees to evaluate the system for learning temporal bone anatomy and surgical approach. Trainees were quizzed on temporal bone anatomy and after 1 hour simulator training; study subjects were asked to perform a cortical mastoidectomy and were assessed by an expert who observed the session. The trainees were then asked to perform the same exercise on a cadaveric temporal bone in the presence of an expert who was able to provide input during the procedure. After simulator instruction as outlined above trainees were able to better identify temporal bone anatomy and were able to perform a cortical mastoidectomy on a cadaveric specimen. Trainees had favorable assessments of the system after training. The authors concluded that virtual reality simulation of temporal bone surgery was an effective method for teaching surgical anatomy and planning.

Conclusions

The conclusions from this project are: 1. A virtual temporal bone dissection system has been developed and compared to cadaveric temporal bones for practice using a multi-center trial. 2. There is no statistical difference seen between practice on the current simulator when compared to practice by human cadaveric temporal bone drilling. 3. Further development is necessary before such systems can be fully integrated into training programs and used for objective skills assessment with the integration of metrics, provision of active user feedback and refinements in structural acquisition and interface design. 4. There is great interest among the otologic community in development of temporal bone simulators for training.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Number 1R01DC006458-01A1 from NIDCD/NIH supported the project described.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Edward Dodson for help with cadaveric temporal bone grading and the following individuals and otolaryngology training programs: Debara L. Tucci, MD – Duke University; Stephen M. Wold – Eastern Virginia University; Michael D. Seidman – Henry Ford Health System; Marlan R. Hansen – University of Iowa; Stacey T. Gray and Joseph B. Nadol, Jr.- Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; Thomas L. Eby – University of Mississippi; Walter Kutz – University of Texas, Southwestern; Kelley M. Dodson – Virginia Commonwealth. Each participated in the multi-institutional validation study voluntarily. The authors would also like to thank Mahmoud Abdel-Rasoul, for assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Primary institutions where work was performed: Ohio Supercomputer Center, The Ohio State University.

Other Institutions where work was performed: Duke University, Eastern Virginia University, Henry Ford Health System, University of Iowa, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, University of Mississippi, University of Texas, Southwestern, Virginia Commonwealth University.

This paper is a Triologic Thesis for Gregory J. Wiet. It was selected by the Triological Society Council to received Honorable Mention in the Mosher clinical research competition and will be presented at the Combined Sections Meeting, January 26–28, 2012.

The authors have no financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Level of Evidence: 1b (Individual randomized controlled trial).

References

- 1.Chio I, Okrainec A. Simulation in Surgery: Perfecting the Practice. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2010 Jun;90(3):457–473. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grass M, Kohler TH, Proksa R. 3D cone-beam CT reconstruction for circular trajectories. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:329–347. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/2/306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler NN, Wiet GJ. Reliability of the Welling scale (WS1) for rating temporal bone dissection performance. Laryngoscope. 2007 Oct;117(10):1803–8. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31811edd7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez SA, Wiet GJ, Butler NN, Welling B, Jarjoura D. Reliability of surgical skills scores in otolaryngology residents: analysis using generalizability theory. Eval Health Prof. 2008 Dec;31(4):419–36. doi: 10.1177/0163278708324444. Epub 2008; Oct 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott J, Clary M, Wiet GJ, Pan T, Huang K. Automatic registration of large data set of microscopic images using high-level features. The Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging; Arlington, VA. April 2006; http://www.pubzone.org/pages/publications/showPublication.do;jsessionid=4E067A493E5F40A827E65D257E0ACF6C?deleteform=true&search=venue&pos=32&publicationId=416610. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiet GJ, Stredney D, Kerwin T, Sessanna D. Dissemination/validation of virtual simulation temporal bone dissection: A project update. Assoc Res Otolaryngol Abs. :718. http://www.aro.org/archives/2006/2006_718.html.

- 7.Nelson RA. Temporal Bone Surgical Dissection Manual. 2. House Ear Institute; Los Angeles, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pluim JP, Maintz JB, Viergever MA. Mutual-information-based registration of medical images: a survey. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2003 Aug;22(8):986–1004. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.815867. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen MS, Mosegaard J, Trier P. The visible ear simulator: A public PC application for GPU-accelerated haptic 3D simulation of ear surgery based on the visible ear data. Otol Neurotol. 2009 Jun;30(4):484–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181a5299b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried MP, Sadoughi B, Gibber MJ, et al. From virtual reality to the operating room: The endoscopic sinus surgery simulator experiment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon-Bowers JA, Bowers C, Procci K. Optimizing Learning in Surgical Simulations: Guidelines from the Science of Learning and Human Performance. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2010 Jun;90(3):583–603. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis HW, Masood H, Laeeq K, Bhatti NI. Defining milestones toward competency in mastoidectomy using a skills assessment paradigm. Laryngoscope. 2010 Jul;120(7):1417–21. doi: 10.1002/lary.20953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laeeq K, Bhatti NI, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Limb CJ, Niparko JK, Minor LM, Francis HW. Pilot Testing of an Assessment Tool for Competency in Mastoidectomy. The Laryngoscope. 2009 Dec;119:2402–2410. doi: 10.1002/lary.20678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sewell C, Morris D, Blevins NH, Agrawal S, Dutta S, Barbagli F, Salisbury K. Validating Metrics for a Mastoidectomy Simulator. In: Westwood JD, et al., editors. Proc MMVR. Vol. 15. IOS Press; Amsterdam: 2007. pp. 421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan D, Wiet GJ, Welling DB, Kerwin T, Stredney D. Creating a cross-institutional grading scale for temporal bone dissection. Laryngoscope. 2010 Jul;120(7):1422–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.20957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zirkle M, Taplin MA, Anthony R, Dubrowski A. Objective Assessment of Temporal Bone Drilling Skills. Annals of Otolgy, Rhinology, & Laryngology. 2007;116(11):793–798. doi: 10.1177/000348940711601101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald S, Alderson D, Powles J. Assessment of ENT registrars using a virtual reality mastoid surgery simulator. J Laryngol & Otol. 2009;123:e14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson A, John NW, Thacker NA, et al. Developing a virtual reality environment in petrous bone surgery: A state-of-the-art review. Otology & Neurotology. 2002;23(2):111–21. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.John NW, Thacker N, Pokric M, et al. An integrated simulator for surgery of the petrous bone. In: Westwood JD, et al., editors. Medicine Meets Virtual Reality. IOS Press; 2001. pp. 218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agus M, Giachetti A, Gobbetti E, et al. A multiprocessor decoupled system for the simulation of temporal bone surgery. Computing and Visualization in Science. 2002;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neri E, Sellari Franceschini S, Berrettini S, et al. IERAPSI project: Simulation of a canal wall-up mastoidectomy. Computer Aided Surgery. 2006;11(2):99–102. doi: 10.3109/10929080600653033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris D, Sewell C, Barbagli F, et al. Visiohaptic simulation of bone surgery for training and evaluation. IEEE Trabs Comput Graph Appl. 2006;26(6):48–57. doi: 10.1109/mcg.2006.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sewell C, Morris D, Blevins NH, et al. Providing metrics and performance feedback in a surgical simulator. Computer Aided Surgery. 2008;13(2):62–81. doi: 10.3109/10929080801957712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Leary SJ, Hutchins MA, Stevenson DR, Gunn C, Krumpholz A, Kennedy G, Tykocinski M, Dahm M, Pyman B. Validation of a networked virtual reality simulation of temporal bone surgery. Laryngoscope. 2008 Jun;118(6):1040–6. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181671b15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.