Abstract

Accumulation of aggregated amyloid-β protein (Aβ) is an important feature of Alzheimer’s disease. There is significant interest in understanding the initial steps of Aβ aggregation due to the recent focus on soluble Aβ oligomers. In vitro studies of Aβ aggregation have been aided by the use of conformation-specific antibodies which recognize shape rather than sequence. One of these, OC antiserum, recognizes certain elements of fibrillar Aβ across a broad range of sizes. We have observed the presence of these fibrillar elements at very early stages of Aβ incubation. Using a dot blot assay, OC-reactivity was found in size exclusion chromatography (SEC)-purified Aβ(1-42) monomer fractions immediately after isolation (early-stage). The OC-reactivity was not initially observed in the same fractions for Aβ(1-40) or the aggregation-restricted Aβ(1-42) L34P but was detected within 1–2 weeks of incubation. Stability studies demonstrated that early-stage OC-positive Aβ(1-42) aggregates were resistant to 4M urea or guanidine hydrochloride but sensitive to 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Interestingly, the sensitivity to SDS diminished over time upon incubation of the SEC-purified Aβ(1-42) solution at 4° C. Within 6–8 days the OC-positive Aβ42 aggregates were resistance to SDS denaturation. The progression to, and development of, SDS resistance for Aβ(1-42) occurred prior to thioflavin T fluorescence. In contrast, Aβ(1-40) aggregates formed after 6 days of incubation were sensitive to both urea and SDS. These findings reveal information on some of the earliest events in Aβ aggregation and suggest that it may be possible to target early-stage aggregates before they develop significant stability.

Keywords: Amyloid-beta protein, aggregation, fibrillar oligomers

1. Introduction

An early event in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the accumulation of aggregated amyloid-β protein (Aβ) which appears to precede tau neurofibrillary tangle formation.[1] Proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid-β precursor protein results in the production of two predominant forms of Aβ monomer, (1-40) and (1-42).[2] Aβ aggregation manifests itself in different forms, the classical dense core neuritic plaques found in the brain parenchyma[3] as well as soluble aggregated species in the AD cortex.[4] While there is significant debate regarding the most deleterious aggregated form of Aβ, there is general agreement on the important role of Aβ(1-42) relative to Aβ(1-40) in AD. The additional two hydrophobic amino acid residues on Aβ(1-42) give the peptide a significantly increased propensity for aggregation[5] and many of the genetic mutations that cause early-onset AD increase the ratio of Aβ(1-42) relative to Aβ(1-40).[6] Furthermore, neuritic plaques consist overwhelmingly of Aβ(1-42)[7] and in vitro studies indicate that Aβ(1-42) forms a greater variety of oligomeric species.[8]

In vitro studies of Aβ aggregation have provided significant kinetic and structural information on the process by which unstructured monomers noncovalently self-assemble into higher-order oligomeric[9, 10], protofibrillar[11–13], and fibrillar[14] states. It is well known that protofibrils and fibrils contain substantial β-sheet structure[15, 16] although less is known about the structure of early aggregation species such as low molecular weight oligomers.

Studies of Aβ aggregation are frequently limited by the capability or sensitivity of particular techniques. Early investigations utilized turbidity[5] or retention of insoluble filtrate[17] to monitor Aβ fibril formation but this method only evaluated the advanced, insoluble, stages of aggregation. Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence can be used to detect the formation of soluble Aβ aggregates but its effectiveness is dependent on the concentration, size, and extent of fibrillar structure as ThT does not bind oligomeric Aβ as well as fibrils.[18] Conventional microscopy methods (atomic force and electron) have provided exceptional macrostructure analysis of protofibrils and fibrils but have been less effective at imaging lower-order oligomeric Aβ species. Given the interest in soluble oligomeric and protofibrillar Aβ species, it remains an important objective to understand some of the early events in Aβ aggregation. One strategy that appears to display significant sensitivity is the development and use of conformation-specific antibodies. These antibodies have been shown to detect particular aggregated species in solution and in human tissue samples and cerebrospinal fluid.[10, 19, 20] One of these, OC antiserum, is able to detect certain elements of fibril structure across a broad spectrum of Aβ aggregate sizes.[21] The soluble population of the OC-positive Aβ species has been termed fibrillar oligomers and these species have been observed in thioflavin-S negative diffuse deposits in human brains[22] demonstrating the high sensitivity of OC antisera for fibrillar structural components in low molecular weight oligomers. In this study we utilized OC antisera to characterize Aβ(1-42) oligomers at their earliest formation and to highlight stark differences between Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Aβ Peptides

Aβ(1-42) was obtained from W.M. Keck Biotechnology Resource Laboratory (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT) in lyophilized form and stored at 20° C. Aβ(1-40) was prepared by solid phase synthesis in the Structural Biology Core at the University of Missouri-Columbia as described previously.[23] Aβ(1-42) L34P was graciously provided by from Dr. Ron Wetzel (Pittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine). Aβ(1-42) peptides were dissolved in 100% hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) at 1 mM, separated into aliquots in sterile microcentrifuge tubes, and evaporated uncovered at room temperature overnight in a fume hood. The following day the aliquots were vacuum-centrifuged to remove any residual HFIP and stored in dessicant at 20° C. Aβ(1-40) peptides were initially treated with 100% trifluoroacetic acid, separated into aliquots in sterile microcentrifuge tubes, and vacuum-centrifuged to dry peptide. The Aβ(1-40) samples were then dissolved in 100% HFIP, dried overnight, and vacuum-centrifuged in the same manner as the Aβ(1-42) peptides.

2.2 Size Exclusion Chromatography

Two different methods were used to prepare Aβ (0.5–1.5 mg) for SEC. For higher yields in the monomer fractions, lyophilized peptides were reconstituted in 10 mM NH4OH containing 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl). The solution was centrifuged at 18,000g for 10 min with a Beckman-Coulter Microfuge 18 and the supernatant was fractionated on a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 column (GE Healthcare) in the desired elution buffer. For yields of both protofibril and monomer, lyophilized Aβ was dissolved in 50 mM NaOH to yield a 2.5 mM Aβ solution. The solution was then diluted to 250 μM Aβ in prefiltered (0.22 μm) buffer of choice, centrifuged and eluted as described above. Prior to injection of Aβ, Superdex 75 column was coated with 2 mg bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) to prevent any non-specific binding of Aβ to the column matrix. Following a 1 mL loading of the sample, Aβ was eluted at 0.5 mL min−1 in the buffer of choice and 0.5 mL fractions were collected and immediately placed on ice. Aβ concentrations were determined by UV absorbance using an extinction coefficient of 1450 cm−1 M−1 at 280 nm. Some Aβ aggregates were prepared by incubation of SEC-purified monomer at room temperature under gentle agitation or quiescent incubation at 37° C. SEC-purification of Aβ in different buffers including Tris-HCl pH 8.0, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4, and F-12 cell culture medium (1 mM NaH2PO4, 14 mM NaHCO3, 131 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 0.003 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose) without phenol red pH 7.4 did not alter the results obtained in the current study. We have recently demonstrated the preparation and isolation of Aβ protofibrils in the physiologically compatible F-12 cell culture medium.[24]

2.3. Thioflavin T fluorescence measurements

Aβ solutions were assessed by ThT fluorescence as described previously.[25] Aβ aliquots were diluted to 5 μM in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 containing 5 μM ThT. Fluorescence emission scans (460–520 nm) were acquired on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer using an excitation wavelength of 450 nm and integrated from 470–500 nm to obtain ThT relative fluorescence values. Buffer controls did not show any significant ThT fluorescence in the absence of Aβ. All ThT fluorescence numbers are reported in relative fluorescence units.

2.4. Dot blot analysis

All steps in the dot blot assay were conducted at 25° C and were modified from the methods previously described.[26] Briefly, 2 μL of Aβ(1-42) at the described concentrations were applied to moist nitrocellulose, allowed to stand for 20 min, and then blocked with 10% milk in PBS with 0.2% Tween 20 (PBST). Following a wash step with PBST, the membrane was incubated with OC serum (1:5000) (gift from R. Kayed, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX) or Ab9 antibody (1:5000) (gift from T. Rosenberry, Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL) for 1 h with gentle shaking, washed, and incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of an anti-rabbit IgG (OC) or anti-mouse IgG (Ab9) HRP conjugate (R&D Systems) for 1 h. After washing, the nitrocellulose membrane was then incubated with enhanced chemiluminescent substrate and exposed to film. The dot blot limit of detection for OC antisera was below 0.045 μg Aβ loaded on the nitrocellulose (i.e. 2 μL of a 5 μM solution) and below 0.009 μg Aβ (i.e. 2μL of a 1 μM solution) for Ab9 antibodies (data not shown).

2.5. Stability Studies

Stability assessment of OC-positive Aβ species was done by incubating SEC-purified protofibrillar or monomeric Aβ for 10 minutes at room temperature with either 4 M urea, 4 M GuHCl or 1% SDS. Following the incubation, 2 μL of the Aβ solution was analyzed by dual dot blots using either Ab9 or OC as the primary antibodies. For long-term SDS stability studies, an Aβ(1-42) monomer fraction was stored at 4° C and the same fraction was assessed for SDS stability on subsequent days as described above.

3. Results

3.1. OC antibody reactivity in Aβ samples directly after SEC-purification

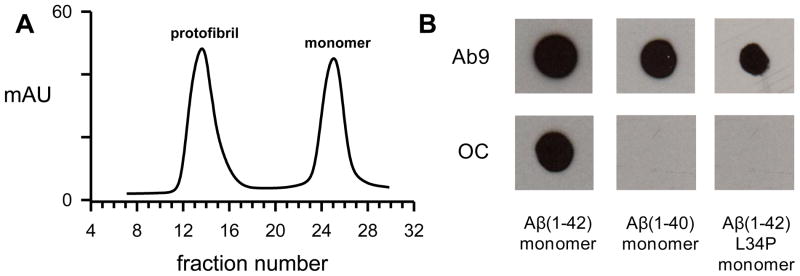

Aβ in lyophilized form was routinely reconstituted at basic pH followed by dilution into neutral buffers and purification by SEC. A representative elution trace is shown in Figure 1A after separation of freshly-reconstituted Aβ(1-42) on a Superdex 75 column. This particular preparation regimen produces an excluded (void) peak containing protofibrils and a single included peak representing low molecular weight (LMW) Aβ.[12] Although LMW Aβ displays non-ideal chromatographic behavior eluting at times indicative of dimer or trimer, numerous experiments including translational diffusion measurements have demonstrated the peak is primarily monomeric[12, 27] but in rapid equilibrium with small amounts of dimers and low-n oligomers.[28, 29] Our own studies have shown that Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40) monomers elute at similar times[24] and multi-angle light scattering in-line with SEC of radiomethylated Aβ(1-40) determined a monomeric molecular weight.[30] Fractions from the monomer peak were assessed for ThT binding/fluorescence and also by dot blot analysis. Primary antibodies used in the dot blot procedure were Ab9, which is selective for N-terminal residues 1–16 and recognizes all conformational forms of Aβ[31], and OC antisera which recognizes structural elements of fibrils but across a wide size spectrum.[21] ThT fluorescence was not present in the monomer fractions for all Aβ peptides tested (data not shown) yet an OC-positive species could be consistently observed in Aβ(1-42) monomer fractions (Fig 1). SEC-purified Aβ(1-40) monomer fractions were not reactive with OC-antisera nor were monomer fractions of Aβ(1-42) L34P. The leucine to proline change at residue 34 slows Aβ(1-42) aggregation[32] thereby enabling the peptide to remain in a monomeric state longer. All three solutions were recognized by Ab9 antibody verifying that the Aβ samples were present and were not desorbed from the nitrocellulose membrane. The data indicated that Aβ(1-42) monomer solutions rapidly acquired particular elements of fibril structure after SEC elution but slower-aggregating Aβ peptides did not.

Figure 1.

An OC-positive species is observed in freshly-purified Aβ(1-42) monomer fractions. Panel A. Aβ(1-42) was reconstituted in NaOH followed by dilution in F-12 medium. The solution was then centrifuged and the supernatant separated on a Superdex 75 column in F-12 medium. The elution shown is a representative experiment of numerous Aβ SEC purifications. Panel B. Aβ monomer fractions from separate SEC purifications were placed on ice immediately after elution from a Superdex 75 column and examined by dot blot analysis within 30 min. The concentration for monomer fractions of Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-42) L34P eluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 was 20 μM and 40 μM respectively, while Aβ(1-40) monomer eluted in PBS was 78 μM.

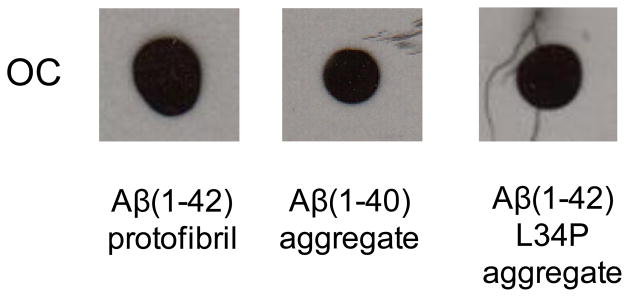

3.2. Development of OC antibody reactivity in Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42) L34P samples

Although Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42) L34P monomer fractions were not reactive with OC-antisera after SEC-isolation the solutions did develop the structural components necessary for OC immunoreactivity after incubation at 37° C for 1–2 weeks (Fig 2). Not surprisingly, Aβ(1-42) protofibrils, which we have documented previously[24, 33], also displayed OC reactivity. In order to rule out that the OC-positive monomer fractions were just elution of very small Aβ species that were formed prior to SEC, a multi-step experiment was carried out. First Aβ(1-40) monomer was reconstituted at high concentration (234 μM) and incubated for 24 hr at 25° C. The sample was then centrifuged and the supernatant eluted on Superdex 75. Fractions enriched in Aβ(1-40) protofibrils and monomers were obtained and evaluated by dot blot along with an aliquot of the supernatant (Fig 3A). The pre-load supernatant and the protofibril fractions were OC-positive while the newly purified monomer fractions were again OC-negative (Fig 3B). All samples in the dot blot were Ab9-positive. The data strongly supports that idea that OC-positivity in Aβ(1-42) monomer fractions reflects early and rapid aggregation events.

Figure 2.

OC-negative monomer fractions develop OC immunoreactivity. Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42) L34P monomer fractions from Figure 1 were incubated quiescently at 37° C for 6 and 13 days respectively and subjected to dot blot analysis. For comparison, an Aβ(1-42) protofibril fraction eluted in the Superdex 75 void volume in F-12 medium without phenol red was also analyzed. 2 μl of each sample at final concentrations of Aβ(1-42) (28 μM), Aβ(1-40) (39 μM), and Aβ(1-42) L34P (20 μM) was used.

Figure 3.

OC-positive Aβ(1-40) species do not elute in the monomer fractions. Panel A. Aβ(1-40) (1.4 mg) was reconstituted in 50 mM NaOH followed by dilution in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 to a concentration of 234 μM. The solution was incubated for 24 hours at 25° C, centrifuged at 18,000g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was eluted on a Superdex 75 column. A continuous 280 nm absorbance elution trace (solid line) and collected 0.5 mL fractions (open circles) are shown. Panel B. Dot blot analysis was performed with Ab9 and OC antibodies for samples taken from the 24 hour supernatant pre-load (40 μM), protofibrils (fraction 13/14 pool) (30 μM) and monomer (fraction 21) (40 μM).

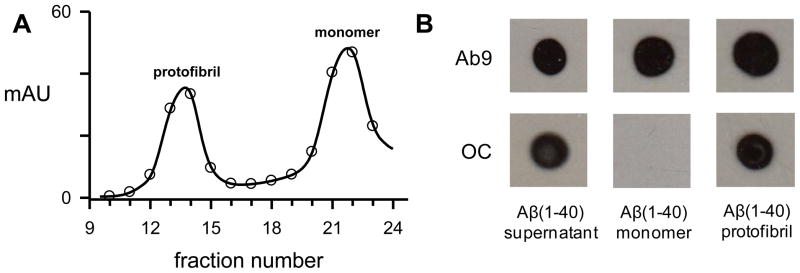

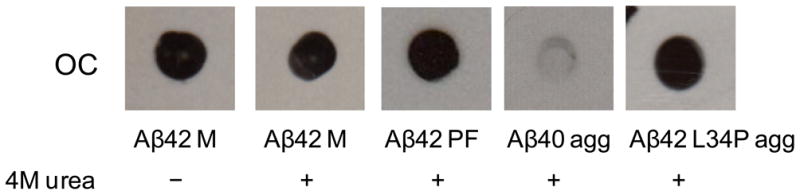

3.3. Stability of freshly-purified OC-positive Aβ(1-42) aggregates in chaotropic agents

The dot blot analysis with the OC antibody revealed an early Aβ(1-42) aggregation species which was detected below the range of a standard ThT fluorescence assay. In order to further probe the properties of this species, stability studies were conducted using chaotropic agents urea and GuHCl. Incubation of Aβ(1-42) solutions obtained from a freshly-isolated SEC monomer fraction with either 4 M urea or 4 M GuHCl (data not shown) did not disrupt the conformational/structural elements necessary for OC immunoreactivity (Fig 4). As expected Aβ(1-42) protofibrils were also resistant to urea and GuHCl. However, aggregated Aβ(1-40) which displayed significant ThT fluorescence was quite sensitive to 4 M urea demonstrating significant stability differences between Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40) (Fig 4). The dot blot analysis showed that while Aβ(1-42) L34P undergoes a significant lag before aggregation, the products are more stable than Aβ(1-40).

Figure 4.

Early OC-positive Aβ(1-42) species is resistant to chaotropic reagents. Stability studies as described in the Methods were conducted on samples taken from (1) a freshly-isolated Aβ(1-42) monomer (M) fraction (1) or protofibril (PF) fraction (2), aggregated (agg) Aβ(1-40) (3) and aggregated Aβ(1-42) L34P (4). The latter three samples are described in Figure 2 legend. The samples were incubated with 4 M urea at a final Aβ concentration of (1) 20 μM, (2) 28 μM, (3) 39 μM and (4) 20 μM. Dot blot analysis was then performed with both Ab9 and OC antibodies. All samples were Ab9-positive (data not shown).

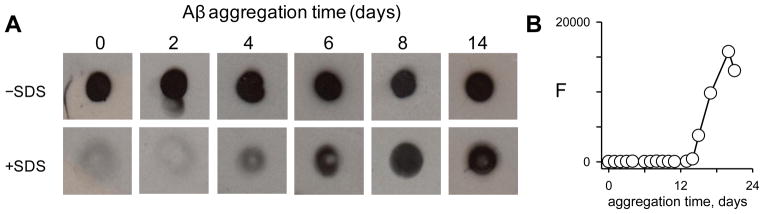

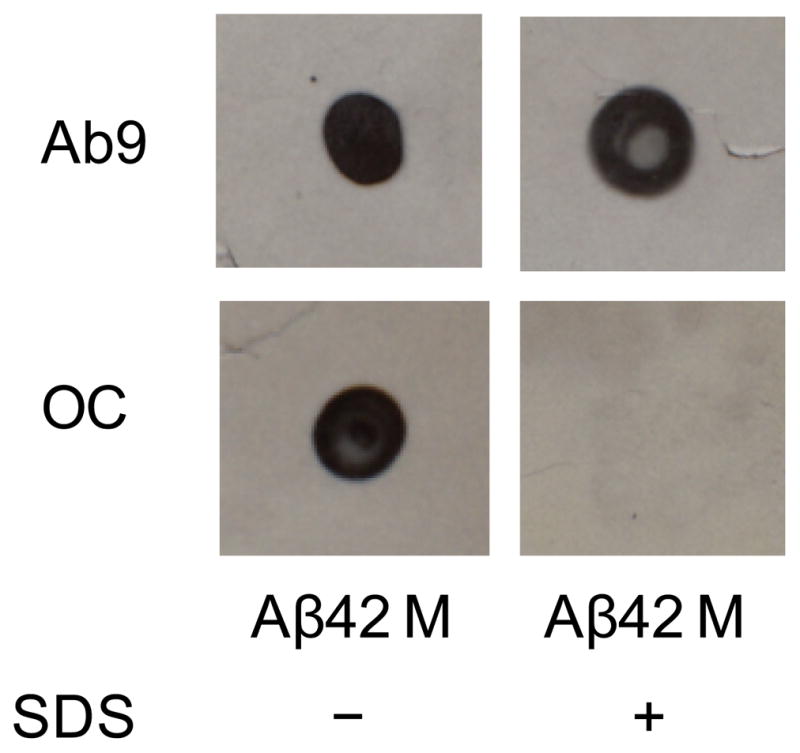

3.4. Stability of freshly-purified OC-positive Aβ(1-42) aggregates in SDS

To further test the stability of the initial OC-positive Aβ(1-42) aggregation species, freshly-isolated Aβ(1-42) from the SEC monomer fraction was incubated with a 1% SDS in a similar manner as with urea and GuHCl. In the presence of SDS the Aβ(1-42) immunoreactivity with OC antibodies was absent (Fig 5). Since Ab9 immunoreactivity was undisturbed, it is likely that the SDS detergent was able to disrupt the OC-positive Aβ(1-42) conformation/structure and the effect was not due to a nonspecific effect on procedural components of the dot blot assay. Retesting of Aβ(1-42) SEC monomer fractions after several weeks revealed that the initial OC-positive and SDS-sensitive species became resistant to SDS. For this reason we investigated the time course of this phenomenon in a new SEC Aβ(1-42) preparation. OC-positive conformational/structural components in a freshly-isolated Aβ(1-42) monomer fraction were again sensitive to 1% SDS but became increasingly resistant to the detergent over time (Fig 6A). All samples in the absence or presence of SDS were Ab9-positive (data not shown). The Aβ(1-42) monomer fraction was immediately placed on ice after SEC elution and stored at 4° C in order to slow the kinetics of aggregation and more readily allow the observation of physical changes. Even at low temperature, the OC-positive Aβ(1-42) sample began showing resistance to SDS around 4 days with no sign of sensitivity by 8 days. Interestingly the transition from SDS-sensitive to SDS-resistant occurred before the first significant observation of ThT fluorescence around 15 days (Fig 6B). Repeated experiments monitoring the transition from SDS-sensitive to SDS-resistant OC-positive species in freshly-isolated Aβ(1-42) monomer fractions revealed variations in the time required to develop resistance yet this transition always occurred prior to onset of ThT fluorescence.

Figure 5.

SDS disrupts Aβ(1-42) OC immunoreactivity. Freshly-isolated Aβ(1-42) from a SEC monomer fraction in F-12 medium without phenol red was incubated with or without 1% SDS as described in the Methods at a final Aβ concentration of 20 μM. Dot blot analysis was performed with both Ab9 and OC antibodies.

Figure 6.

Early OC-positive Aβ(1-42) species becomes resistant to SDS over time. Freshly-isolated Aβ(1-42) from a SEC monomer fraction in F-12 medium without phenol red was stored at 4° C without disturbance over 24 days. Panel A. At chosen time points after isolation the Aβ(1-42) solution (final concentration 20 μM) was incubated with or without 1% SDS for 10 min at 25° C and then analyzed by dot blot with Ab9 and OC antibodies. Panel B. Thioflavin T fluorescence measurements were taken of stored Aβ(1-42) solution at various time points.

4. Discussion

4.1. SEC-purification of Aβ peptides

The current report describes the use of OC antibodies to observe very early aggregation events in the Aβ fibril formation pathway. Clear differences were demonstrated between Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42) in both the rate of formation of OC-positive structures and the stability of the OC-positive species. These observations were made immediately after SEC purification and well before more common techniques such as ThT fluorescence detected the presence of fibrils.

SEC has been used frequently in Aβ preparation to remove preexisting aggregated material and produce a homogenous protein solution.[34] Furthermore, this technique has been very effective at separating protofibrillar and monomeric Aβ.[12, 29] The isolated monomer, while the predominant species, has been shown to be in rapid equilibrium with lower-order oligomers and, at sufficient concentrations (μM), with higher-order oligomers.[34] The data in this report confirm that this equilibrium is established rapidly and that within this mixture, for Aβ(1-42), are species that already contain components of fibril structure and are stable in the presence of some denaturants. The finding that SEC-purified Aβ(1-40) monomer fractions were not reactive to OC antibodies provided an opportunity to strengthen the premise that the very early, de novo, stages of Aβ fibril formation can be observed and studied following SEC isolation.

4.2. OC recognition of fibrillar structural elements

The initial characterization of OC antiserum by Glabe and coworkers found that soluble, OC-positive Aβ(1-42) aggregates eluted on SEC across a broad range of sizes including LMW (monomer/dimer) fractions.[21] This observation was interpreted as the elution of pre-formed fibrillar oligomers that represent small pieces of fibrils or fibril nuclei. The findings from our current study whereupon SEC-separation of an OC-positive Aβ(1-40) aggregation solution yielded OC-negative monomer suggests an additional explanation that OC antibodies not only recognize preformed fibrillar oligomers but newly formed species at the earliest stages of Aβ assembly. The rapid oligomerization of Aβ(1-42) compared to Aβ(1-40) has previously been described as well as the difficulty in isolating a completely monomeric Aβ(1-42) fraction.[8] Our findings add to those studies and reveal that at very early Aβ(1-42) aggregation times, fibrillar structural components already begin to appear. Strengthening this analysis is the lack of OC-reactivity of SEC-purified Aβ(1-42) L34P monomer confirming the aggregation-restricted nature of the proline-substituted peptide[32] and ability of OC antisera to distinguish newly-formed oligomeric species with components of fibril structure from pure monomer.

4.3. Sensitivity and resistance of early Aβ aggregates to chaotropic agents and detergents

The stability findings were remarkable in that even at very early aggregation times (within minutes after SEC-isolation of monomer fractions), Aβ(1-42) fibrillar oligomers demonstrated significant stability in the presence of 4 M urea. In fact, the newly-formed OC-positive Aβ(1-42) species were much more stable than longer-term Aβ(1-40) aggregates that displayed relatively high levels of ThT fluorescence. The rapid development of fibril-like structure in the Aβ(1-42) oligomers and their resistance to denaturants such as urea and GuHCl highlight the striking differences between Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40) and underscore the importance of intervention strategies that reduce the Aβ(1-42):Aβ(1-40) ratio.

The transition of the OC-positive Aβ(1-42) material in the freshly-isolated SEC monomer fractions from SDS-sensitive to SDS-resistant implies that structural changes are likely occurring in the early stages of aggregation. These may include the initial formation of the hydrogen-bonded β-sheet network that ultimately becomes the core of mature fibrils or simply extension of this network to a critical size that is still below the ThT binding/detection limit. Additional mechanisms of increased stabilization may include continued addition of monomers and/or coalescence of separate fibrillar oligomers.

Conformation-specific antibodies appear to be an important tool in examining structural aspects in the early stages of protein aggregation. These antibodies offer advantages in sensitivity compared to other techniques such as ThT fluorescence, circular dichroism, light scattering, and microscopy. Once more detailed structural data is obtained on the oligomeric species and the epitope that these antibodies recognize; they may yield even more information on Aβ assembly pathways. In conclusion, we have demonstrated the de novo formation of the earliest elements of fibril structure in SEC-purified monomeric Aβ(1-42) solutions based on recognition by OC antiserum. The rapid development of these fibril structural elements were not observed in similarly-prepared Aβ(1-40) solutions highlighting differences between the two peptides at the earliest stages of aggregation. Furthermore, this report is the first to show significant stability differences between OC antisera-positive Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40) oligomers that contain elements of fibril structure and to observe the time-dependent development of SDS-resistant stability in early-stage Aβ(1-42) oligomers.

Highlights.

We observed fibrillar structural elements at very early stages of Aβ incubation.

We compared the formation of these elements between Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40).

We identified stability differences between Aβ(1-42) and Aβ(1-40) oligomers.

We demonstrated the development of SDS resistance in early Aβ(1-42) oligomers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Award Number R15AG033913 from the National Institute on Aging (MRN).

We would like to thank Dr. Rakez Kayed (University of Texas Medical Branch), Dr. Charles Glabe (University of California-Irvine), and Dr. Suhail Rasool (University of California-Irvine) for providing us with the OC antiserum used in this study.

Abbreviations used

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid-β protein

- GuHCl

guanidine hydrochloride

- HFIP

hexafluoroisopropanol

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- ThT

thioflavin T

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomark Med. 2010;4:51–63. doi: 10.2217/BMM.09.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD, Odaka A, Otvos L, Jr, Eckman C, Golde TE, Younkin SG. An increased percentage of long amyloid β protein secreted by familial amyloid β protein precursor (βAPP717) mutants. Science. 1994;264:1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selkoe DJ. Cell biology of protein misfolding: The examples of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin M, Shepardson N, Yang T, Chen G, Walsh D, Selkoe DJ. Soluble amyloid β-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5819–5824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT., Jr The carboxy terminus of the β amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: Implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy J. Amyloid, the presenilins and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:154–159. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Jr, Younkin LH, Suzuki N, Younkin SG. Amyloid β protein (Aβ) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at Aβ40 or Aβ42(43) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7013–7016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assembly: Aβ40 and Aβ42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:330–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper JD, Wong SS, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT., Jr Observation of metastable Aβ amyloid protofibrils by atomic force microscopy. Chem Biol. 1997;4:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh DM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid βprotein fibrillogenesis: Detection of a protofibrillar intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22364–22372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper JD, Wong SS, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT., Jr Assembly of Aβ amyloid peptides: an in vitro model for a possible early event in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8972–8980. doi: 10.1021/bi9904149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper JD, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT., Jr Atomic force microscopic imaging of seeded fibril formation and fibril branching by the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-β protein. Chem Biol. 1997;4:951–959. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh DM, Hartley DM, Kusumoto Y, Fezoui Y, Condron MM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Selkoe DJ, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis: Structure and biological activity of protofibrillar intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25945–25952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. A structural model for Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Multhaup G, Paradis Md, Vonsattel JP, Gusella JF, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Tanzi RE. Rapid induction of Alzheimer Aβ amyloid formation by zinc. Science. 1994;265:1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.8073293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Culyba EK, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Amyloid-β forms fibrils by nucleated conformational conversion of oligomers. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric Aβ ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee EB, Leng LZ, Zhang B, Kwong L, Trojanowski JQ, Abel T, Lee VM. Targeting amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) oligomers by passive immunization with a conformation-selective monoclonal antibody improves learning and memory in Aβ precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4292–4299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kayed R, Head E, Sarsoza F, Saing T, Cotman CW, Necula M, Margol L, Wu J, Breydo L, Thompson JL, Rasool S, Gurlo T, Butler P, Glabe CG. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarsoza F, Saing T, Kayed R, Dahlin R, Dick M, Broadwater-Hollifield C, Mobley S, Lott I, Doran E, Gillen D, Anderson-Bergman C, Cribbs DH, Glabe C, Head E. A fibril-specific, conformation-dependent antibody recognizes a subset of Aβ plaques in Alzheimer disease, Down syndrome and Tg2576 transgenic mouse brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:505–517. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0530-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonough RT, Paranjape G, Gallazzi F, Nichols MR. Substituted tryptophans at amyloid-β(1-40) residues 19 and 20 experience different environments after fibril formation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;514:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paranjape GS, Gouwens LK, Osborn DC, Nichols MR. Isolated amyloid-β(1-42) protofibrils, but not isolated fibrils, are robust stimulators of microglia. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:302–311. doi: 10.1021/cn2001238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Lin WL, Mukhopadhyay R, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Growth of β-amyloid(1-40) protofibrils by monomer elongation and lateral association. Characterization of distinct products by light scattering and atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6115–6127. doi: 10.1021/bi015985r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng BP, Esler WP, Clish CB, Stimson ER, Ghilardi JR, Vinters HV, Mantyh PW, Lee JP, Maggio JE. Deposition of monomeric, not oligomeric, Aβ mediates growth of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaques in human brain preparations. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10424–10431. doi: 10.1021/bi990718v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bitan G, Teplow DB. Preparation of aggregate-free, low molecular weight amyloid-beta for assembly and toxicity assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;299:3–9. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-874-9:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jan A, Hartley DM, Lashuel HA. Preparation and characterization of toxic Aβ aggregates for structural and functional studies in Alzheimer’s disease research. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1186–1209. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Cratic-McDaniel S, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Amyloid-β protofibrils differ from amyloid-β aggregates induced in dilute hexafluoroisopropanol in stability and morphology. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2471–2480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kukar T, Murphy MP, Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Weggen S, Smith TE, Ladd T, Khan MA, Kache R, Beard J, Dodson M, Merit S, Ozols VV, Anastasiadis PZ, Das P, Fauq A, Koo EH, Golde TE. Diverse compounds mimic Alzheimer disease-causing mutations by augmenting Aβ42 production. Nat Med. 2005;11:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nm1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams AD, Portelius E, Kheterpal I, Guo JT, Cook KD, Xu Y, Wetzel R. Mapping Aβ amyloid fibril secondary structure using scanning proline mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ajit D, Udan ML, Paranjape G, Nichols MR. Amyloid-β(1-42) fibrillar precursors are optimal for inducing tumor necrosis factor-α production in the THP-1 human monocytic cell line. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9011–9021. doi: 10.1021/bi9003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teplow DB. Preparation of amyloid β-protein for structural and functional studies. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:20–33. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]