Abstract

To review studies on hypertension in Nigeria over the past five decades in terms of prevalence, awareness and treatment and complications. Following our search on Pubmed, African Journals Online and the World Health Organization Global cardiovascular infobase, 1060 related references were identified out of which 43 were found to be relevant for this review. The overall prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria ranges from 8%-46.4% depending on the study target population, type of measurement and cut-off value used for defining hypertension. The prevalence is similar in men and women (7.9%-50.2% vs 3.5%-68.8%, respectively) and in the urban (8.1%-42.0%) and rural setting (13.5%-46.4%).The pooled prevalence increased from 8.6% from the only study during the period from 1970-1979 to 22.5% (2000-2011). Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension were generally low with attendant high burden of hypertension related complications. In order to improve outcomes of cardiovascular disease in Africans, public health education to improve awareness of hypertension is required. Further epidemiological studies on hypertension are required to adequately understand and characterize the impact of hypertension in society.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Hypertension, Prevalence, Non-communicable disease, Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a common, important and major global public health problem[1].

Its prevalence has been found to be 44% in Western Europe and 28% in North America. It has been documented as a threat to the health of people in sub-Saharan Africa and a major contributor to morbidity and mortality in the sub-region[2-4]. There is emerging evidence to show that the pattern of diseases in sub-Saharan Africa is changing, with non-communicable diseases (NCD) responsible for about 22% of the total deaths in the region in 2000, cardiovascular disease alone accounting for 9.2% of the total mortality [World Health Organization (WHO) 2002]. According to Kearney et al[5], by 2025 about 75% of the world hypertensive population will be in developing countries. In Nigeria for example, it is the number one risk factor for stroke, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and kidney failure. With an increasing adult population as well as rising prevalence of hypertension, Nigeria will experience economic and health challenges due to the disease if the tide is not arrested. As far back as the early 60s a lot of interest has been shown by workers on the blood pressure of Nigerian Africans. The essence of this work is to review studies on hypertension as well as hypertension research in the country.

COUNTRY PROFILE

Nigeria is classified as a low-middle income country with a Gini Index of 43.7 and income per capita of $1490. 49% of the population is living in urban areas, the gross national income per capita is $2070. Life expectancy at birth is 51 years for both sexes (53 for men and 54 for women).The probability of dying between 15 and 60 years for men and women (per 1000 population) is 377 and 365 respectively. The mortality rate for under 5s is 138/1000 and the maternal mortality ratio is 840/105 live births. Non-communicable diseases contribute about 14% of the number of years of life lost. The number of doctors/10 000 population is about 4. Five point one percents of men and 9.0% of women aged 20 years and above are obese; 11.9% of men and 1.0% of women aged 15 years and above smoke cigarettes.

The prevalence of HIV (per 1000 adults aged 15-49 years) is 36 while the prevalence of tuberculosis (per 100 000 population) is 497[6-8].

METHODS

The Pubmed scientific database was searched from 1950-2011 for studies of blood pressure and hypertension in the country. The search criteria were “Hypertension”, “High Blood Pressure” and “Nigeria”. Studies conducted mainly on adult subjects were included.

Additional references were sought from retrieved publications. The African index medicus, African Journal Online and WHO Global cardiovascular infobase were also searched.

All the data collected were entered into an excel spreadsheet. Information collected include: first author’s name, year of publication, place of study, study design, population, sample size, mean age range, proportion of women enrolled, mean age, and prevalence of hypertension in the sample population as well as in men and women.

The pooled prevalence rate of hypertension was computed for the period 1970-1979, 1990-1999, and 2000-2011 from community-based studies.

RESULTS

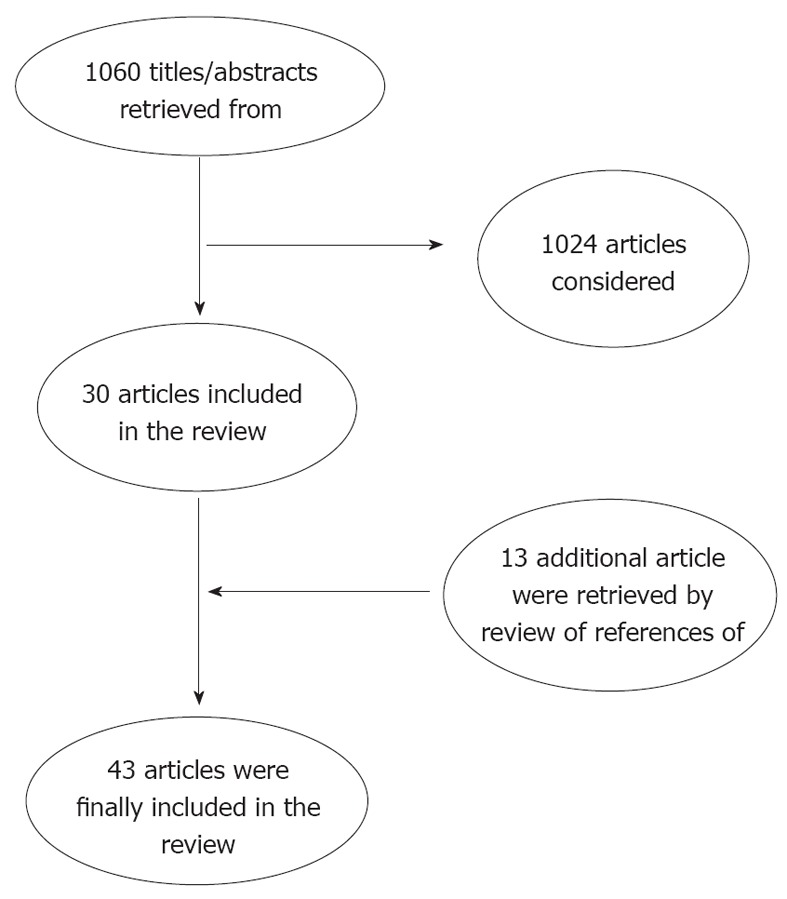

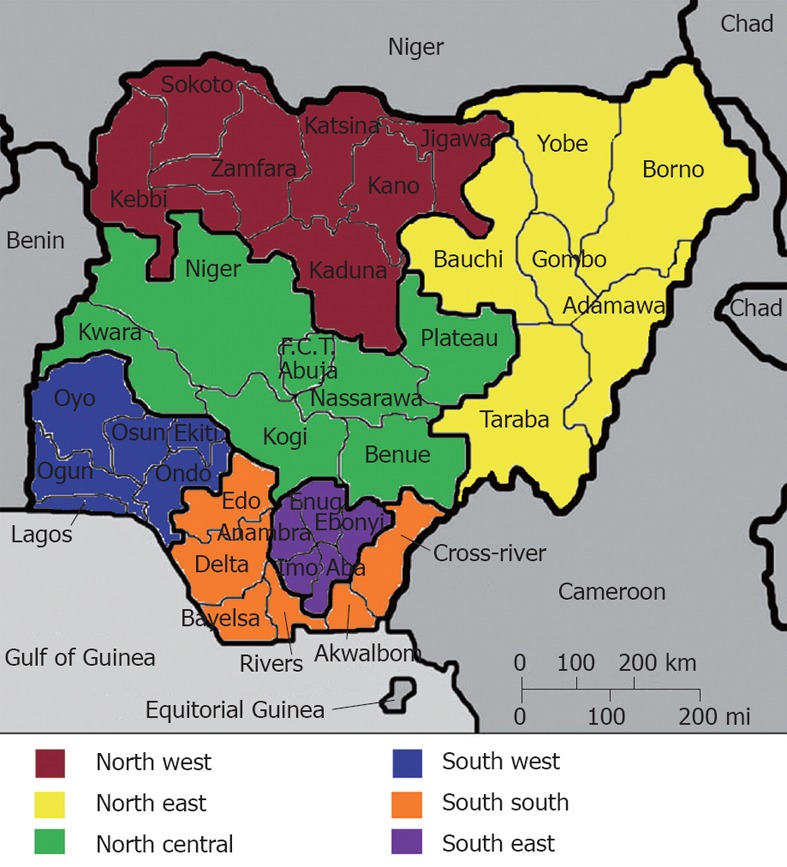

Our search yielded a total of 1060 references. However 30 publications were found to be useful for this review. An additional 13 articles were retrieved through the review of the bibliography of the earlier obtained articles. Figure 1 is a summary of the selection process. These cross-sectional studies were published between 1960 and 2012 in 12 of the 36 states of Nigeria: Oyo[9-22], Enugu[23-27], Lagos[28,29], Osun[30,31], Edo[32-35], Cross-River[36,37], Akwa-Ibom[37], Rivers[38], Kastina[39], Sokoto[40], Borno[41] and Abia[42]. Three of the studies involved more than one state[37,43].

Figure 1.

Selection process.

In terms of geopolitical spread, the majority of studies were conducted in the Southwestern part of the country; some of the studies were conducted before 1990 while the majority were after 1990.

Historical vignette

Many years ago it was generally believed that high blood pressure was rare in native Africans. This was based on reports mainly by workers on the eastern coast of the continent such as Cooke[44], Donnison[45], Jex-Blake[46] and Vint[47].

The earliest report of hypertension in Nigerian Africans was probably by Callander[48]. He commented on the blood pressure of army recruits and Nigerian soldiers at routine medical examination. He noted that in 100 healthy soldiers, 52 had a systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg, and 23 had a diastolic blood pressure (BP) > 90 mmHg.

His observations from the army recruits were more remarkable. In 400 recruits aged between 19-24 years, 42.5% were rejected on account of elevated blood pressure and “this after an hour’s rest and amytal sedation before the pressure was recorded”.

In two reports in 1956, hypertension was documented as a cause of cardiovascular disease in Nigerians.

Beet et al[49] noted that it was responsible for 34% of cases of heart failure in Northern Nigeria while Nwokolo et al[50] also documented some cases in Enugu in the Eastern part of the country. Also Lambo et al[51] reported on the association of high blood pressure and mental disorder in elderly psychiatric patients in the Western region.

The earliest and first large scale study of blood pressure in Nigerians was by Abrahams et al[11]. The study was conducted in a rural town of Ilora which is about 50 km north of Ibadan. They noted, like most other studies conducted during that period, in Caucasians and American Blacks that blood pressure rose with age in both men and women. However, they did not document any clear relationship between blood pressure, weight climate and diet. This was followed by studies by Smith[28] in Lagos, Akinkugbe et al[9] in Ibadan, Johnson[52] in Lagos, Oviasu et al[32-35] in Benin city and Oyediran in Epe near Lagos.

Akinkugbe is generally regarded as the father and doyen of blood pressure and hypertension research in Nigeria because of his seminal work in this field in the late 60s and 70s[9,10,53-62]. He documented that: (1) Systolic blood pressure rose with age in both sexes and in all age groups from 12-70 years. This trend was less marked in diastolic blood pressure; (2) Blood pressure levels were similar in women from rural and urban areas but seemed much higher in urban than in rural men; (3) The rate of rise of pressure was more rapid in earlier decades than subsequently; (4) There was little correlation with weight and much less so with height after 40 years of age; (5) The incidence of proteinuria was highest in the early teenage group years, but did not relate to blood pressure trends; and (6) Casual systolic and diastolic pressure differed in no important respects from those in Negro populations in the Caribbean, but systolic and diastolic values are marginally higher in United States Negroes than in West Indian or West African Negroes”.

Cole et al[63] was the first to conduct a drug trial on hypertensive patients and this was followed by a series of work by Salako et al[64-69]. Falase et al[70-72] demonstrated the lack of effect of low doses of prazosin in the treatment of hypertension in Nigeria.

A series of studies by Salako and Falase showed that Nigerians responded well to thiazide diuretics and calcium channel antagonists when these drugs were used as monotherapy. Other classes of drugs, such as beta adrenergic blockers, require the use of high doses before they are effective in Nigerian hypertensives. The use of high doses of these drugs often causes unacceptable side effects. These classes of antihypertensive drugs are, however, effective in low doses when they are combined with either thiazide diuretics or calcium channel antagonists or both. Effective management of hypertension in Nigerians therefore requires the use of thiazide diuretics or calcium channel antagonists as monotherapy or in combination with other classes of antihypertensive agents.

Osuntokun et al[73-76] first studied hypertension in diabetic subjects in the country and showed in many seminal research studies the contribution of hypertension as a risk factor for stroke in hospital based and population based studies. Akerele documented hypertension in Nigerian children in 1974. The relation of renal disease, hypertension and schistosomiasis was explored by Soyannwo et al[77-81].

Table 1 shows the hypertension research from 1961-1981.

Table 1.

Events in the first 21 years of blood pressure and hypertension research in Nigeria (1961-1981)

| No. | Author | Year | Comments |

| 1 | Abrahams et al[11] | 1961 | First population based study of blood pressure in the country. Studied the systemic blood pressure of rural Nigerians resident in Ilora |

| 2 | Monekosso[82] | 1964 | Reported some cases in a clinical survey of a village in South West Nigeria |

| 3 | Smith[28] | 1966 | Studied blood pressure of urban inhabitants in Lagos |

| 4 | Akinkugbe[56] | 1968 | Documented the rarity of hypertensive retinopathy in Nigerians |

| 5 | Akinkugbe et al[57] | 1968 | Reported on the rarer causes of hypertension in Nigeria |

| 6 | Akinkugbe et al[9] | 1968 | Wrote on arterial blood pressure in rural Nigerians in Eruwa |

| 7 | Akinkugbe[58] | 1969 | Reported on the hypertensives diseases in Ibadan , Nigeria |

| 8 | Akinkugbe[60] | 1969 | Wrote on antihypertensive therapy in the African context |

| 9 | Ojo et al[83] | 1969 | Studied hypertension in pregnancy |

| 10 | Akinkugbe[59] | 1969 | Reported on the result of his survey of blood pressures in school children |

| 11 | Cole et al[63] | 1970 | First documented drug trial (Declinax) in hypertensive Nigerians |

| 12 | Brockington[84] | 1971 | Reported on postpartum hypertensive heart failure |

| 13 | Johnson[52] | 1971 | Reported on his study of blood pressure in rural areas around Lagos |

| 14 | Carlisle[85] | 1971 | Reported on the remission of hypertension in some Nigerians |

| 15 | Salako[64] | 1971 | First trial of oral thiazides |

| 16 | Salako[65] | 1971 | Reported on serum electrolytes in hypertensive Nigerians |

| 17 | Salako[66] | 1972 | Reported on electrolyte changes following thiazide therapy in hypertensive Nigerians |

| 18 | Osuntokun et al[73,74] | 1972 | Seminal work on hypertension in diabetic Nigerians |

| 19 | Salako et al[67] | 1973 | Evaluated the usefulness of Moduretic in the treatment of hypertension in Nigerians |

| 20 | Akinkugbe et al[61] | 1974 | Reported on the experience with beta blockers in hypertension management |

| 21 | Aderele[86] | 1974 | Documented on hypertension in Nigerian children |

| 22 | Akinkugbe[87] | 1976 | Studied blood pressure in non-pregnant women |

| 23 | Falase et al[70] | 1976 | Demonstrated lack of effect of low dose prazosin in hypertensive Nigerians |

| 24 | Etta et al[88] | 1976 | Assessed the relation of blood pressure to indices of obesity |

| 25 | Olatunbosun et al[89] | 1976 | Evaluated the relation of blood pressure to heavy metals |

| 26 | Jain et al[90] | 1977 | Reported on the incidence of hypertension in Abuth Zaria |

| 27 | Akinkugbe et al[62] | 1977 | Conducted a biracial study of blood pressure in school children |

| 28 | Olatunde et al[91] | 1977 | Trial of beta blockers in hypertensive Nigerians |

| 29 | Osuntokun et al[75,76] | 1977 | Demonstrated through hospital registry and population based studies that hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke in Nigeria |

| 30 | Abdurrahman et al[92] | 1978 | Studied blood pressure in school children in Northern Nigeria |

| 31 | Mabadeje[93] | 1979 | Conducted a trial of chlorthalidone in hypertensive Nigerians |

| 32 | Falase et al[71,72] | 1979 | Documented poor response of hypertensive Nigerians to Beta blockers monotherapy |

| 33 | Alakija[94] | 1979 | Pilot study of hypertension in Benin City |

| 34 | Abengowe et al[95] | 1980 | Reported on the pattern of hypertension in Northern Savannah |

| 35 | Oviasu et al[32-35] | 1980 | Document on blood pressure and hypertension in urban city of Benin/ Occupational factors in hypertension |

| 36 | Ladipo[96] | 1981 | Carried out a study on hypertensive retinopathy in Ile-Ife |

Diagnosis of hypertension

Earlier studies used 160/95 mmHg as the benchmark for the diagnosis of hypertension. The vast majority of studies which were conducted in the last 20 years used 140/90 mmHg as the cut off.

Twenty of the studies were carried out in urban populations, 11 in rural communities, while the remaining 6 were conducted both in urban and rural populations. The majority of the population based studies used multi-stage cluster sampling.

Sampling in five of the studies was by convenience (during free medical programmes).

The sample size in the studies ranged from 132 to 4930 subjects. The proportion of women who participated ranged from 24.9% to 71.2% while the mean age of the population ranged from 31.6 years to 61.2 years.

Prevalence of hypertension

The prevalence of hypertension in both men and women ranged from 8% to 46.4%; with regards to gender, the prevalence of hypertension ranged from 7.9% to 50.2% and 3.5% to 6.8.8% in men and women, respectively. The reported prevalence in rural areas ranged from 13.5%-46.4% in both sexes, 14.7%-49.5% in men and 14.3-68.8% in women. Data from urban studies revealed a range of 8.1%-42.0% in both men and women, 7.9%-46.3% for men and 3.5%-37.7% for women. In general hypertension prevalence was higher in urban than rural areas (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of hypertension in 38 studies in Nigeria (1960-2011)

| No. | First author | Year | Study location | State | Region | BP cut off | Target population | Setting | Sample size | % all | % men | % women |

| 1 | Abrahams et al[11] | 1960 | Ilora | Oyo | SW | 160/90 | Community based | Rural | 457 | 13.3 | NA | NA |

| 2 | Smith[28] | 1961 | Lagos | Lagos | SW | 160/95 | Hospital based | Urban | 207 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 7.9 |

| 3 | Akinkugbe et al[9,10] | 1968 | Eruwa | Oyo | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 3602 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 11.2 |

| 4 | Johnson[52] | 1971 | Lagos | Lagos | SW | 160/95 | Community based | Urban | 1392 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 9.9 |

| 5 | Jain et al[90] | 1977 | Kaduna | Kaduna | NW | 160/95 | Hospital based | Urban | 2950 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 4.9 |

| 6 | Oviasu et al[32,33] | 1978 | Isi-uwa | Edo | SS | 160/100 | Community based | Rural | 1482 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 0.5 |

| 7 | Oviasu et al[34,35] | 1980 | Benin city | Edo | SS | 140/90 | Civil servants | Urban | 1265 | 13.3 | 14 | 10 |

| 8 | Idahosa[110] | 1987 | Benin city | Edo | SS | 140/90 | Civil servants | Urban | 1450 | 15.1 | NA | NA |

| 9 | Ogunlesi et al[12] | 1991 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 160/95 | Male factory workers | Urban | 541 | 8 | ||

| 10 | Ekpo et al[36] | 1992 | Calabar | Cross river | SS | 160/95 | Civil servants, factory workers, plantain workers | Urban | 4382 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 3.5 |

| 11 | Bunker et al[111] | 1992 | Benin city | Edo | SS | 140/90 | Civil servants | Urban | 559 | 20-43 | 21.6 | 12.5 |

| 12 | Kaufman et al[16] | 1996 | Ibadan | Eyo | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Urban | 205 | 11 | ||

| 13 | Kaufman et al[17] | 1996 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 140/90 (160/95) | Rural farmers/urban poor/retired railway workers | Rural/urban | 598 | 14,25,29 (3,11,14) | - | - |

| 14 | Cooper et al[112] | 1997 | National | National | National | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 2509 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 14.3 |

| 15 | Akinkugbe[113] | 1997 | National | National | National | 160/95 | Community based | Rural/urban | 4930 | 10.7 | ||

| 16 | Owoaje et al[14] | 1997 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Urban | 247 | 23.4 | 22.2 | 24.3 |

| 17 | Kadiri et al[114] | 1999 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 160/95 | Civil servants | Urban | 917 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 8 |

| 18 | Olatunbosun et al[13] | 2000 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 160/95 | Civil servants | Urban | 998 | 10.3 | 13.9 | 5.3 |

| 19 | Lawoyin et al[20] | 2002 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 140/90 | Community cohort | Urban | 2144 | 12.4 | 12.1 | 12.7 |

| 20 | Onyemelukwe[115] | 2003 | Lagos | Lagos | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural/urban | 1082 | SHT 22.5, DHT 24.7 | NA | NA |

| 21 | Akinkugbe[116] | 2003 | Lagos | Lagos | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural/urban | 1018 | 34.8 | 36.2 | 33.5 |

| 22 | Erhun et al[117] | 2005 | Ile-ife | Osun | SW | 140/90 | University community | Urban | 1000 | 21 | 23.3 | 16.4 |

| 23 | Oghagbon et al[118] | 2008 | Ilorin | Kwara | NC | 140/90 | Factory workers | Urban | 281 | 27.1 | 28.4 | 22.9 |

| 24 | Omuemu et al[98] | 2007 | Udo | Edo | SS | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 590 | 20.2 | 26.2 | 13.2 |

| 25 | Ukoh[119] | 2007 | Benin city | Edo | SS | 140/90 | Hospital based | Urban | 2852 | 20.2 | NA | NA |

| 26 | Nwankwo et al[41] | 2008 | Maiduguri | Borno | NE | 140/90 | Community based | Rural/urban | 224 | 40 (urban), 27.8 (rural) | ||

| 27 | Adedoyin et al[31] | 2008 | Ile-ife | Osun | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 2250 | 18.7 | 15.5 | 21 |

| 28 | Ekore et al[21] | 2009 | Ibadan | Oyo | SW | 140/90 | Hospital based | Urban | 405 | 30.6 | 34.4 | 28.2 |

| 29 | Ulasi et al[26] | 2010 | Njodo Nike, Enugu | Enugu | SE | 140/90 | Community based | Semi-urban/rural | 1939 | 35.4 (urban), 25.1 (rural) | NA | NA |

| 30 | Ekwunife et al[99] | 2010 | Nsukka | Enugu | SE | 140/90 | Community based | Urban | 756 | 30 | 40.3 | 24.7 |

| 31 | Sani et al[39] | 2010 | Katsina | Katsina | NW | 140/90 | Hospital based | Urban | 300 | 25.7 | 27.9 | 24 |

| 32 | Adegoke et al[30] | 2010 | Ile-ife | Osun | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 132 | |||

| 33 | Oladapo et al[22] | 2010 | Egbeda | Oyo | SW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 2000 | 20.8 | 21.1 | 20.5 |

| 34 | Ahaneku et al[27] | 2011 | NA | Enugu | SE | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 218 | 44.5 | 49.5 | 42.3 |

| 35 | Onwubere et al[24] | 2011 | Ezeagu | Enugu | SE | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 858 | 46.4 | 31.2 | 68.8 |

| 36 | Ejim et al[23] | 2011 | Imezi owa, | Enugu | SE | 140/90 | Community based | Rural (middle age/elderly) | 858 | 50.2 | 44.8 | |

| 37 | Ulasi et al[25] | 2011 | Enugu | Enugu | SE | 140/90 | Traders | Urban | 731 | 42 | 46.3 | 37.7 |

| 38 | Hendriks et al[120] | 2011 | Afon and Ajasse Ipo | Kwara | NC | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 2678 | 19.3 | NA | NA |

| 39 | Isezuo et al[40] | 2011 | Sokoto | Sokoto | NW | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 782 | 24.8 | 25.9 | 23.6 |

| 40 | Andy et al[37] | 2012 | CRS/AK | CRS/AK | SS | 140/90 | Community Based | Rural | 3869 | 23.6 | 31.2 | 18.1 |

| 41 | Onwuchekwa et al[38] | 2012 | Kegbara-Dere | Rivers | SS | 140/90 | Community based | Rural | 1078 | 18.3 | - | - |

| 42 | Odugbemi et al[121] | 2012 | Lagos | Lagos | SW | 140/90 | Traders | Urban | 400 | 34.8 | - | - |

| 43 | Ogah et al[42] | 2012 | Abia | Abia | SE | 140/90 | Community | Rural/urban | 2983 | SHT 31.4, DHT 22.5 | Rural: SHT 33.5, DHT 23.4; Urban: SHT 33.6, DHT 20.6 | Rural: SHT 30.5, DHT 25.4; Urban: SHT 26.4, DHT 18.4 |

SW: South west; SE: South east; SS: South south; NW: North west; NE: North east; NC: North central; NA: Not available; SHT: Systolic hypertension; DHT: Diastolic hypertension; BP: Blood pressure.

Pooled prevalence and trend: A prevalence of 8.9% was estimated from the only community-based study available for 1970-1979. For 1990-1999, the pooled prevalence of hypertension was 15.0% (CI 13.7-16.3). The pooled prevalence increased significantly to 22.5% (CI 21.8-23.2) from 2000 to 2009.

Impact of blood pressure cut-off threshold on the prevalence of hypertension: In a study of the prevalence and patterns of hypertension in a semi-urban community in South Western Nigeria, Adedoyin et al[31] demonstrated that with a cut-off value of ≥ 140/90 mmHg for the diagnosis of hypertension, the prevalence was 36.6% (isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) in 22.1% and isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH) in 14.5%).

On the other hand when the threshold was increased to 160/95 mmHg, only 13.35% were found to be hypertensive (6.63% had both ISH and IDH).

A male:female ratio of 1.7:1 and 1:5 was documented for blood pressure of ≥ 140/90 mmHg and ≥ 160/90 mmHg, respectively.

Impact of age: In all the studies, the most likely determinant of blood pressure and presence of high blood pressure was age. BP was shown to increase steadily with age from the youngest to the oldest age brackets, irrespective of gender.

It appears that population mean blood pressure has increased over the years since the first survey by Abrahams et al[11]. This may be due to an increase in detection rather than a temporal increase as the observation is limited by a lack of serially conducted studies in any of the populations.

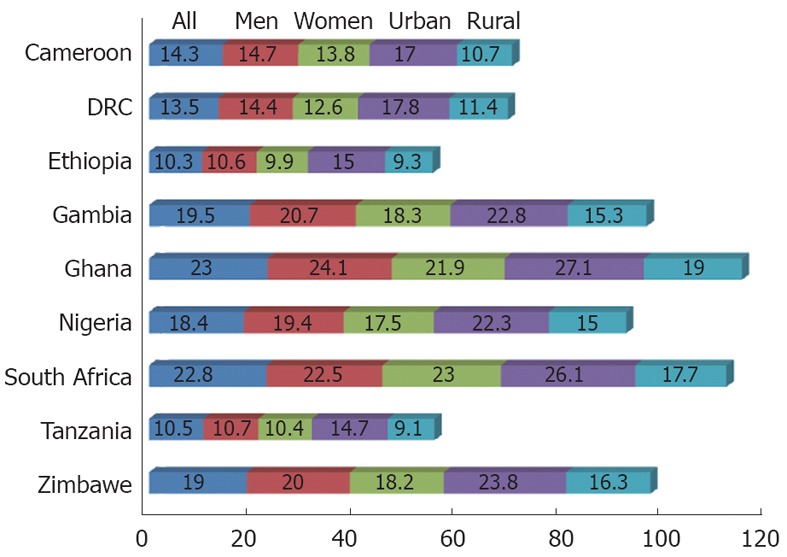

Comparison of prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria with some other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa: Figure 2 shows the comparison of prevalence of hypertension in different parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria, as estimated for 2008 by Twagirumukiza et al[97]. The overall prevalence of hypertension was put at 18.4% for Nigeria compared with a prevalence of 10.35% for Ethiopia and 23.0% for Ghana (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Map of Nigeria showing the 36 states and federal capital territory as well as the 6 geopolitical zones.

Figure 3.

Comparision with other countries.

Hypertension awareness, treatment and control

As in many populations of the world, the awareness of hypertension is low in Nigeria. In four of the studies, the reported awareness rates were 14.2% in rural areas by Oladapo et al[22], 18.5% in Edo State[98], and 29.4% and 30.0% in semi-urban and urban populations in Enugu State[25,26].

The proportion of hypertensives on treatment was reported to be 21% (23.7% men, 17.5% women) by Ekwunife et al[99] and 18.6% (19.0% men, 18.4% women) by Oladapo et al[22].

Blood pressure control was poor; it was reported as 9% (5% in men and 17.5% in women) by Ekwunife et al[99].

Studies on pathophysiology of hypertension in Nigeria

Osotimehin et al[100] estimated plasma Na+-K+ ATPase inhibitor by a technique in which it competes with ouabain for binding on red cells in normotensives without a family history of hypertension, normotensives with a family history of hypertension and hypertensive individuals. They observed that plasma levels of the inhibitor were significantly higher in the last two groups and that this correlated positively with urinary sodium excretion in the three groups.

In another study, the author demonstrated low renin activity in hypertensive Nigerians[101].

Ogunlesi et al[102] and Aderounmu et al[103] studied intracellular sodium and blood pressure and showed that erythrocyte sodium (ENa) was higher in hypertensives compared with normal controls. ENa also correlated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Obasohan et al[104] went further to demonstrate higher sodium-lithium counter-transport (SLC) activity and ENa levels both in hypertensive subjects and their offspring.

In a more recent study, Adebiyi et al[105] showed that plasma noradrenaline level was higher in hypertensive subjects compared to control subjects. Hypertensive Nigerians also have lower levels of plasma renin, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). Systolic blood pressure positively correlated with plasma noradrenaline but negatively with renin, ACE and ANP. This finding of high noradrenaline levels in hypertensive Nigerians supports the hypothesis that activation of the sympatho-adrenergic system might play a dominant role in the pathophysiology of hypertension in Nigerians.

Several workers have also demonstrated higher salt taste and salt taste threshold in hypertensive individuals as well as their offspring compared to their normotensive counterparts[106-108].

However such a relationship was not demonstrated in adolescent school children[109].

Hypertension related admissions in Nigeria

In a review of the prevalence of hypertension and its complications among medical admissions in Enugu, South Eastern Nigeria, 18% (1360 subjects out of the 7399 admissions in the period between December 1998 and November 2003) had hypertension related diseases. Hypertensive congestive cardiac failure accounted for 26.5% of cases and 46.1% of hypertension related complications. Hypertension with its complications accounted for more than two-thirds (69.6%) of the cardiovascular system admissions[122,123].

In a three year review of adult hypertensive admissions in Benin city (South-South Nigeria), Ukoh[119] reported that 575 out of the total of 2852 adult medical admissions in Benin were as a result of high blood pressure related morbidities. The most common hypertensive complications were stroke, congestive cardiac failure and chronic kidney failure.

In another report from the same region, stroke was the commonest cause of death at the medical emergency room of the University of Portharcourt teaching hospital[124].

In a review of 424 hypertension related admissions in the same hospital (173 males and 251 females, aged 18-100 years with a mean of 56.5 ± 16.2); stroke was responsible for 169 (39.9%) hypertensive complications. “Heart failure occurred in 97 (22%) cases while renal failure and encephalopathy accounted for 40 (9.4%) and 7 (1.7%) hypertensive complications, respectively. There were 99 deaths out of which 51 (51.5%) were due to stroke, 14 (14.12%) were due to heart failure, and 12 (12.1%) were due to renal failure”[125].

During the same period, 191 of the hypertension related admissions died giving a case fatality of 42.9%. Eighty six (45%) of the deaths occurred during acute hypertensive crises such as stroke, hypertensive encephalopathy and acute renal failure. Other important complications leading to death included heart failure (17.3%) and renal failure (16.8%)[125].

High blood pressure also contributed to the burden of adult medical admissions in Uyo (Southern Nigeria): hypertension related heart failure, stroke or severe uncontrolled hypertension. This was shown to be commoner in the wet seasons of the year[126].

In Sokoto (Northwestern Nigeria), Isezuo et al[127] documented hypertension related admissions in 440 subjects admitted in a tertiary centre between 1995 and 2000. Hypertension related morbidities included heart failure (36.4%), stroke (34.8%) and chronic renal failure in 7.1% and other conditions in 21.7%. Hospital admissions for hypertension related morbidities were more generally higher in the rainy season than the dry season.

Kolo et al[128] studied hypertension related admissions and outcomes in a tertiary hospital in Bauchi (North Eastern Nigeria). They documented that out of the 3108 admissions into the medical ward of the hospital, 735 (23.7% were related to hypertension with an excess mortality of 42.9%. Stroke was the commonest complication, accounting for 44.4% of cases and had the highest mortality (39.3%). This was followed by chronic kidney disease (36.6%), hypertensive emergencies (30.9%) and heart failure which had the least intrahospital mortality of 27.5%.

Hypertensive target organ damage in Nigeria

Hypertensive target organ damage (TOD) is common in Nigeria. Because of low awareness of hypertension in the country, hypertensive TOD is often what brings patients to healthcare facilities.

Oladapo et al[129] recently reported the results of the study of the prevalence and pattern of TOD and associated clinical conditions in 415 hypertensive individuals in a rural community in Southwestern Nigeria. 179 (43.1%) of the participants had evidence of TOD and 45 (10.8%) had established cardiovascular disease. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was present in 27.9%, atrial fibrillation in 16.4%, microalbuminuria in 12.3% and overt proteinuria in 15.3%.

Furthermore stroke was present in 6.3%, heart failure in 4.6%, retinopathy in 2.2%, ischaemic heart disease in 1.7% and peripheral vascular disease in 3.6%. TOD was significantly higher in those with severe hypertension and diabetes mellitus. In a related study but in younger subjects aged 18-44 years, Ekore et al[21] examined 124 individuals for TOD. LVH was present in 22 (17.7%), chronic cardiac failure in 3 (2.4%), retinopathy in 5 (4.0%), nephropathy in 12 (26.1%) and transient ischaemic attacks in one patient (0.8%)

Ayodele et al[130] examined 203 patients in an outpatient clinic in Abeokuta and documented LVH in 31%, heart failure in 10.8%, chronic kidney disease (CKD) in 18.2% and stroke in 8.9%.

Hypertensive heart disease

Various aspects of hypertensive heart disease (HHD) have been studied in the country - such as LVH, LV geometry, left atrial structure, function and dysfunction, LV diastolic function and dysfunction, LV systolic function and right ventricular function. The burden of arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities has also been reported in compensated and asymptomatic hypertensives in the country.

Left ventricular hypertrophy: The prevalence of ECG LVH in hypertensive subjects varies from 18%-56% depending on the criteria used. Sokolow-Lyon-Rappaport voltage criteria have the best sensitivity (80%) and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. Romhilt-Estes score was reported to have the best specificity[131].

In another Nkado et al[132] noted a significant correlation of ECG voltage with echocardiographically determined LV mass.

ECG LVH with strain pattern has also been shown to have a worse LV structure and systolic function in hypertensive Nigerians[133].

Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: LV diastolic dysfunction has been demonstrated in hypertensive Nigerians by various workers[134-138]. Furthermore it has also been demonstrated in offspring of hypertensive individuals. Adamu et al[137] reported LV diastolic dysfunction in 62% of hypertensive subjects compared to 11.3% in age and sex-matched controls. Impaired relaxation was the commonest LV filling pattern.

Adebayo et al[139] demonstrated early diastolic dysfunction in hypertensives using a newer method of evaluation (tissue doppler imaging). In another study, the authors evaluated left atrial structural and functional alterations in hypertension which was found to be statistically different compared to age and sex-matched apparently normal individuals[140].

LV systolic dysfunction: In a study of 832 unselected hypertensive subjects, Ogah et al[141] documented LV systolic dysfunction (LVSD) in 18.1% of the participants (mild LVSD = 9.6%, moderate LVSD = 3.7% and severe LVSD = 4.8%).

LV mass, body mass index and male gender were found to be independent predictors of LVSD in the study.

The Tei index (index of global myocardial performance) was found to be significantly higher in hypertensives compared to controls. This index also increased with severity of hypertensive heart failure. It was found to be inversely related to LV ejection fraction and directly related to some indexes of diastolic function such as E/A ratio and deceleration time[142].

Echocardiographic LVH and LV geometric patterns: Adebiyi et al[143] studied the prevalence and pattern of LVH in a large population of hypertensive Nigerians seen at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. The prevalence of LVH ranged from 30.9%-56.0% depending on the method of indexation employed.

Abnormal LV geometry was documented in 61.1%-74.0% and was commoner in the female gender.

Correlates of LV mass in hypertensive Nigerians: Ogah et al[144] assessed the correlates and determinants of LV mass in 285 hypertensive individuals. The authors found that diastolic blood pressure, family history of hypertension, alcohol consumption, left atrial size; LV wall stress and tension were the independent predictors of LV mass (LVM) in these hypertensive subjects.

Right ventricular function and dysfunction: Karaye et al[145] reported right ventricular diastolic dysfunction (RVDD) and right ventricular systolic dysfunction (RVSD) in 61.7% and 32%, respectively, of 128 individuals with high blood pressure in Kano. RVSD was highest in those with eccentric LVH. Age was found to be the only determinant of RVDD while LV ejection fraction was a predictor of RVSD after adjusting for confounding variables. In a similar study, Akintunde et al[146] reported RV structural and functional alteration in hypertension and concluded that RVDD may be an early precursor of HHD in Nigerians.

The burden of arrhythmias in hypertensive Nigerians: Hypertension and LVH are both risk factors for atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias.

Okeahialam et al[147] studied 1547 ECG tracings obtained from well compensated hypertensive patients over a 5-year period in Jos to determine the burden of arrhythmias. About 10% of patients had one form of arrhythmia or another. The common arrhythmias were ventricular ectopic (133, 86.9%) atrial ectopic (21, 13.7%) and atrial fibrillation (10, 6.5%). Others included sinus arrhythmia in 3 (1.9%), sinus escape beats in 3 (1.9%), wandering pacemaker in 3 (1.9%) and Wolf Parkinson White in 1 (0.7%). Factors associated with the presence of arrhythmias include: age, presence of ECG LVH and left atrial enlargement.

Conduction abnormalities: In the same study, Okeahialam et al[147] noted the following conduction abnormalities in 1547 well compensated hypertensive patients. First degree AV block was present in 7 while 6 subjects had right bundle branch block and left bundle branch block.

Hypertension as a risk factor for heart failure in Nigeria: Hypertension is by far the commonest risk factor for congestive heart failure in Nigeria. In the Abeokuta heart failure (HF) registry, hypertension was responsible for 78.7% of HF in the city. It was also responsible for 62.6%, 56.3%, 57% and 44.1% of heart failure cases in Abuja[148], Port Harcourt[149], Jos[150] and Uyo[126] respectively. In the recently published transnational study of HF in sub-Saharan Africa, hypertension was clearly shown as the predominant cause of HF in the region, especially in Nigeria. Ogah et al[151] recently described the characteristics of 197 subjects with hypertensive HF in the Abeokuta HF registry. The mean age of the subjects was 58.4 years which is 15-20 years younger than the mean age of patients with HF in the developed world. The male to female ratio was 1.4:1. HF in hypertensive Nigerians was characterized by severe LV systolic dysfunction (65.5%) and abnormal LV geometry (concentric and eccentric LVH). Intrahospital mortality was 3.6%.

It has also been noted that most of the patients diagnosed as having dilated cardiomyopathy in Nigeria are cases of hypertensive heart failure with poor myocardial failure because of poor or no control[152,153].

Hypertension as a major risk factor for stroke in Nigeria

Stroke is currently a major public health problem in Nigeria. As in many developing countries of the world it has some peculiarities. It occurs at a younger age with associated high mortality and disability adjusted life years.

Available hospital based studies in Nigeria suggest there are rising rates of stroke in the country[154].

Available data, at least from hospital based studies, show that stroke accounts for 0.23%-4.0% of all hospital admissions, 0.5%-45% neurological admissions and 5%-17% of deaths on medical wards. It is the commonest cause of neurological admission in Lagos, the largest city and the commercial nerve centre of Nigeria. Cerebral infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage, respectively, are responsible for 64%, 19% and 6% of strokes in the country[154].

In a community based study in Lagos[155], stroke prevalence was estimated as 1.14 per 1000 (1.51/1000 in men, 0.69/1000 in women and 24.1/1000 in those older than 65 years.

The mortality associated with stroke in Nigeria is high with 30 d case fatality ranging from 28% to 40%[154].

In a 10-year review of stroke in Sagamu, Ogun State, stroke accounted for 2.4% of all emergency admissions. Forty nine percent had cerebral infarction, 45% intracerebral haemorrhage and 6% SAH. The studies further showed that 1.8% of all deaths at the emergency room were due to stroke. Case fatality at 24 h, 7 d, 30 d and 6 mo were 9%, 28%, 40% and 46%, respectively[154]. In the year 2007, mortality from stroke in the country was put at 126/100 000 population[156].

In Nigeria, as in most developing countries, hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for stroke. It is present in almost 80% of cases. Unfortunately most victims are unaware of their blood pressure status prior to the event[157].

Hypertension as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease in Nigeria

Hypertension is a major cause of CKD and chronic renal failure (CRF) in Nigeria. In Enugu (South East) and Benin City (South South), hypertension is the commonest cause of CKD and CRF[158,159]. It is only second to chronic glomerulonephritis in the South West[160-163]. Hypertension induced CRF in Nigeria is four times commoner in men than women with a male: female ratio of 4.3:1. Severe throbbing frontal headache and nocturia are common. The duration of hypertension is usually between 2-15 years. It is associated with a history of cigarette smoking, poor compliance to anti-hypertensive medications, family history of hypertension, severe/accelerated hypertension and severe uraemia. The presence of other hypertension related TOD, such as heart failure and retinopathy, is common. Mortality is high, 51% within the first 12 mo of diagnosis. Renal histological findings include glomerular sclerosis, malignant arteriolar changes and absence of glomerular cellular proliferation[164,165].

Hypertension and coronary artery disease in Nigeria

Hypertension is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) in Nigeria. Anjorin et al[166] recently reviewed 87 patients with CAD seen over a period of 22 years (1983-2004) at the University of Maiduguri teaching hospital. Hypertension was identified as a risk factor in 53%, diabetes in 41%, cigarette smoking in 39%, hypercholesterolemia in 29% and obesity in 20%.

Hypertensive retinopathy in Nigeria

In a review of 407 patients with retinal diseases in Ile-Ife (Southwest) by Onakpoya et al[167], hypertensive retinopathy was responsible for 12% of cases. In Ibadan, hypertensive retinopathy is the 9th commonest cause of retinal diseases and responsible for 4.6% of cases[168]. It is also responsible for 7.7% of all retinal/optic nerve disorders and 0.1% of ocular disorders in a rural community in northern Nigeria. In Enugu (South East), hypertensive retinopathy is responsible for 13% of vitreo-retinal diseases in a tertiary healthcare facility[169].

DISCUSSION

Since the creation of the Nigerian state in 1960, a lot of studies have been undertaken to provide information on the burden of hypertension in the country. This includes a national survey which was conducted in 1997[113]. It is pertinent, however, to note that most studies provided crude prevalence of the condition in the country. In addition, there are a lot of variations in the studies in terms of target population as well as criteria for diagnosis. Earlier studies used 160/95 mmHg (occasionally 160/90 mmHg) while the most recent ones used 140/90 mmHg as a cut off mark for the diagnosis of hypertension. The age structure in most of the studies is essentially middle age and represents the age structure of the Nigerian population, except in few studies that purely targeted middle age or elderly populations[15,23]. In many of the studies, the prevalence of hypertension was higher in men than in women at least up to the age of 40 years when the prevalence equalized[9,10,26,32]. This picture is similar to findings in other Africans, African Americans and in Blacks in the Caribbean[112].

The higher prevalence in the urban population may indicate differences in lifestyle. Urban populations are more likely to eat processed foods which are high in salt and fat content. Obesity which is a risk factor for hypertension is also higher in urban areas than in rural areas because of reduced physical activity.

In a few of the studies, especially in the Eastern part of the country, hypertension was found to be as high in the rural population as it is in the urban population[27]. This picture has been documented in some United States and European studies[170-173]. It is likely that those rural populations may be older as most old people move to rural areas after retirement from active service.

Hypertension awareness range from 3.5% in Sokoto to 30% in Nsukka[22,25,26,40,99]. There was no remarkable gender difference. Treatment ranged from 11.9%-21%[40,99]. In two studies the treatment rate was slightly higher in men than in women; however the control rate was significantly higher in women than in men (17.5% and 5%, respectively).

The higher detection rate in men than women is at variance with data from most parts of Africa and other parts of the world. Women are more likely to be detected during antenatal visits and are also more likely to accept the diagnosis of hypertension.

On the other hand, the blood pressure control rate is better in women than in men. Women are more likely to attend clinics for follow-up.

In general, hypertension and other chronic diseases awareness, treatment and control is generally low in the country as in most developing countries. These diseases are often asymptomatic and in most cases presentation is when complications have set in.

Emerging data from hospital studies show that hypertension or its complications is the commonest NCD in Nigeria. In 1961, hypertension related illnesses contributed to 8.8% of all medical admission in Lagos[28]. Abengowe et al[95] reported 9.3% in Kaduna in 1980. Recent data from the country indicated a rate of 28% in Port-Harcourt[124] and 21% in Benin City[119]. This is comparable to a rate of 30% from Tanzania[174].

In conclusion, hypertension in Nigeria today is the commonest risk factor for stroke, heart failure, ischemic heart disease and chronic kidney disease[175].

There is, therefore, a need to encourage health promotion in the population as means of primary prevention. There is also a need for increased public health education to increase the awareness of hypertension and the sequelae. Hypertension control programmes need to be established in communities in the country and more community based screening programmes for cardiovascular disease risk factors and NCDs need to be carried out. There is also a need to carry out research on the reasons for regional differences in prevalence of hypertension as well as reasons for lack of urban-rural differences in some areas in the country. The lack of scientific data to measure trends in the country should also be addressed.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Giuseppe Mule, MD, Department of Medicina Interna, Malattie Cardiovascolari e Nefrourologiche, Chair of Internal Medicine, European Society of Hypertension Centre of Excellence, University of Palermo, Via del Vespro, 129, 90127 Palermo, Italy; Wei-Chuan Tsai, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, 138 Sheng-Li Road, Tainan 704, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, Kastarinen M, Poulter N, Primatesta P, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper R. Cardiovascular mortality among blacks, hypertension control, and the reagan budget. J Natl Med Assoc. 1981;73:1019–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper R, Rotimi C. Hypertension in blacks. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:804–812. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper RS, Liao Y, Rotimi C. Is hypertension more severe among U.S. blacks, or is severe hypertension more common? Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:173–180. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(96)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Bank. Nigeria. 2012. Available from: http: //data.worldbank.org/country/nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IMF. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects. 2012. Available from: http: //www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=21&pr.y=3&sy=2009&ey=2012&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=694&s=NGDPD,NGDPDPC,PPPGDP,PPPPC,LP&grp=0&a= [Google Scholar]

- 8.CIA. Nigeria. 2012. Available from: https: //www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akinkugbe OO, Ojo AO. The systemic blood pressure in a rural Nigerian population. Trop Geogr Med. 1968;20:347–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinkugbe OO, Ojo OA. Arterial pressures in rural and urban populations in Nigeria. Br Med J. 1969;2:222–224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5651.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahams DG, Alele CA, Barnard BG. The systemic blood pressure in a rural West African community. West Afr Med J. 1960;9:45–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogunlesi A, Osotimehin B, Abbiyessuku F, Kadiri S, Akinkugbe O, Liao YL, Cooper R. Blood pressure and educational level among factory workers in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Hum Hypertens. 1991;5:375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olatunbosun ST, Kaufman JS, Cooper RS, Bella AF. Hypertension in a black population: prevalence and biosocial determinants of high blood pressure in a group of urban Nigerians. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:249–257. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owoaje EE, Rotimi CN, Kaufman JS, Tracy J, Cooper RS. Prevalence of adult diabetes in Ibadan, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadiri S, Salako BL. Cardiovascular risk factors in middle aged Nigerians. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufman JS, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Rotimi CN, McGee DL, Cooper RS. Obesity and hypertension prevalence in populations of African origin. The Investigators of the International Collaborative Study on Hypertension in Blacks. Epidemiology. 1996;7:398–405. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman JS, Owoaje EE, James SA, Rotimi CN, Cooper RS. Determinants of hypertension in West Africa: contribution of anthropometric and dietary factors to urban-rural and socioeconomic gradients. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1203–1218. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman JS, Rotimi CN, Brieger WR, Oladokum MA, Kadiri S, Osotimehin BO, Cooper RS. The mortality risk associated with hypertension: preliminary results of a prospective study in rural Nigeria. J Hum Hypertens. 1996;10:461–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman JS, Tracy JA, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Cooper RS. Lifestyle, education, and prevalence of hypertension in populations of African origin. Results from the International Collaborative Study on Hypertension in Blacks. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawoyin TO, Asuzu MC, Kaufman J, Rotimi C, Owoaje E, Johnson L, Cooper R. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in an African, urban inner city community. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:208–211. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v21i3.28031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekore RI, Ajayi IO, Arije A. Case finding for hypertension in young adult patients attending a missionary hospital in Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:193–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oladapo OO, Salako L, Sodiq O, Shoyinka K, Adedapo K, Falase AO. A prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a rural Yoruba south-western Nigerian population: a population-based survey. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21:26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ejim EC, Okafor CI, Emehel A, Mbah AU, Onyia U, Egwuonwu T, Akabueze J, Onwubere BJ. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the middle-aged and elderly population of a nigerian rural community. J Trop Med. 2011;2011:308687. doi: 10.1155/2011/308687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onwubere BJ, Ejim EC, Okafor CI, Emehel A, Mbah AU, Onyia U, Mendis S. Pattern of Blood Pressure Indices among the Residents of a Rural Community in South East Nigeria. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:621074. doi: 10.4061/2011/621074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulasi II, Ijoma CK, Onwubere BJ, Arodiwe E, Onodugo O, Okafor C. High prevalence and low awareness of hypertension in a market population in enugu, Nigeria. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:869675. doi: 10.4061/2011/869675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulasi II, Ijoma CK, Onodugo OD. A community-based study of hypertension and cardio-metabolic syndrome in semi-urban and rural communities in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahaneku GI, Osuji CU, Anisiuba BC, Ikeh VO, Oguejiofor OC, Ahaneku JE. Evaluation of blood pressure and indices of obesity in a typical rural community in eastern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2011;10:120–126. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.82076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AJ. Arterial hypertension in the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. West Afr Med J. 1966;15:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith AJ. Hypertension in the African. Lancet. 1969;1:372. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adegoke OA, Adedoyin RA, Balogun MO, Adebayo RA, Bisiriyu LA, Salawu AA. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a rural community in Nigeria. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:59–62. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adedoyin RA, Mbada CE, Balogun MO, Martins T, Adebayo RA, Akintomide A, Akinwusi PO. Prevalence and pattern of hypertension in a semiurban community in Nigeria. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:683–687. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32830edc32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oviasu VO. Arterial blood pressures and hypertension in a rural Nigerian community. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1978;7:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oviasu VO, Okupa FE. Occupational factors in hypertension in the Nigerian African. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1979;33:274–278. doi: 10.1136/jech.33.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oviasu VO, Okupa FE. Arterial blood pressure and hypertension in Benin in the equatorial forest zone of Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1980;32:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oviasu VO, Okupa FE. Relation between hypertension and occupational factors in rural and urban Africans. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58:485–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekpo EB, Udofia O, Eshiet NF, Andy JJ. Demographic, life style and anthropometric correlates of blood pressure of Nigerian urban civil servants, factory and plantation workers. J Hum Hypertens. 1992;6:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andy JJ, Peters EJ, Ekrikpo UE, Akpan NA, Unadike BC, Ekott JU. Prevalence and correlates of hypertension among the Ibibio/Annangs, Efiks and Obolos: a cross sectional community survey in rural South-South Nigeria. Ethn Dis. 2012;22:335–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onwuchekwa AC, Mezie-Okoye MM, Babatunde S. Prevalence of hypertension in Kegbara-Dere, a rural community in the Niger Delta region, Nigeria. Ethn Dis. 2012;22:340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sani MU, Wahab KW, Yusuf BO, Gbadamosi M, Johnson OV, Gbadamosi A. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors among apparently healthy adult Nigerian population - a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isezuo SA, Sabir AA, Ohwovorilole AE, Fasanmade OA. Prevalence, associated factors and relationship between prehypertension and hypertension: a study of two ethnic African populations in Northern Nigeria. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:224–230. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nwankwo EA, Ene AC, Biyaya B. Some Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Volunteers for health checks: A Study Of Rural And Urban Residents In The Northeast Nigeria. The Internet Journal of Cardiovascular Research. 2008:5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogah OS, Madukwe OO, Chukwuonye II, Onyeonoro UU, Ukaegbu AU, Akhimien MO, Onwubere BJC, Okpechi IG. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in Abia State Nigeria: Results from the Abia State Non-Communicable diseases and Cardiovascular Risk factors Survey. Ethn Dis. 2012:In press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The National Expert Committee. Non-Communicable Disease in Nigeria. Report of a National Survey. Ibadan: Federal Ministry of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooke AR. Notes on the disease met with in Uganda, Central Africa. J Trop Med. 1901;4:175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donnison CP. Blood pressure in the African natives: its bearing upon aetiology of hyperplasia and arteriosclerosis. Lancet. 1929;1:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jex-Blake AJ. High blood pressure. East Afr Med J. 1934;10:286–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vint FW. Postmortem findings in natives of Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1937;13:332–340. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Callander WH. Blood pressure in Nigerian soldiers and army recruits. West Afr Med J. 1953;2:02–103. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beet EA. Rheumatic heart disease in Northern Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1956;50:587–592. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(56)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nwokolo C. Endomyocardial fibrosis and other obscure cardiopathies in eastern Nigeria. West Afr Med J. 1955;4:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lambo TA. Psychiatric syndromes associated with cerebrovascular disorders in the African. J Ment Sci. 1958;104:133–143. doi: 10.1192/bjp.104.434.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson TO. Arterial blood pressures and hypertension in an urban African population sample. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1971;25:26–33. doi: 10.1136/jech.25.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akinkugbe OO, Brown WC, Cranston WI. Pressor effects of angiotensin infusions into different vascular beds in the rabbit. Clin Sci. 1966;30:409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akinkugbe OO, Brown WC, Cranston WI. The direct renal action of angiotensin in the rabbit. Clin Sci. 1966;30:259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akinkugbe OO, Brown WC, Cranston WI. Response to angiotensin infusion before and after adrenalectomy in the rabbit. Am J Physiol. 1967;212:1147–1152. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.212.5.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akinkugbe OO. The rarity of hypertensive retinopathy in the African. Am J Med. 1968;45:401–404. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akinkugbe OO, Jaiyesimi F. The rarer causes of hypertension in Ibadan. (An eleven-year study) West Afr Med J Niger Pract. 1968;17:82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Akinkugbe OO. Hypertensive disease in Ibadan, Nigeria. A clinical prospective study. East Afr Med J. 1969;46:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akinkugbe OO. School survey of arterial pressure and proteinuria in Ibadan, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1969;46:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akinkugbe OO. Antihypertensive treatment in the African context. Practitioner. 1969;202:549–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akinkugbe OO, Carlisle R, Olatunde IA. Proceedings: Beta-adrenergic blockers in the treatment of hypertension: experience with propranolol at the U.C.H. Ibadan, Nigeria. West Afr J Pharmacol Drug Res. 1974;2:63P–64P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akinkugbe OO, Akinkugbe FM, Ayeni O, Solomon H, French K, Minear R. Biracial study of arterial pressures in the first and second decades of life. Br Med J. 1977;1:1132–1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6069.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cole TO, Adadevoh BK. Clinical evaluation of Declinax in Nigerian hypertensives. Br J Clin Pract. 1970;24:245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salako LA. Oral thiazide diuretics in the treatment of hypertension in Nigeria. West Afr Med J Niger Pract. 1971;20:320–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salako LA. Serum electrolytes in hypertension in Nigerians. Clin Chim Acta. 1971;34:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(71)90073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salako LA. Serum electrolytes during long term treatment of hypertension with thiazide diuretics in Nigerians. West Afr Med J Niger Med Dent Pract. 1972;21:104–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salako LA, Falase AO. Clinical evaluation of moduretic in the treatment of arterial hypertension. Niger Med J. 1973;3:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salako LA, Falase AO, Aderounmu AF. Comparative beta-adrenoreceptor-blocking effects and pharmacokinetics or propranolol and pindolol in hypertensive Africans. Clin Sci (Lond) 1979;57 Suppl 5:393s–396s. doi: 10.1042/cs057393s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salako LA, Falase AO, Aderounmu AF. Placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of alprenolol in African hypertensive patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 1979;6:358–363. doi: 10.1185/03007997909109451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Falase AO, Salako LA, Aminu JM. Lack of effect of low doses of prazosin in hypertensive Nigerians. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1976;19:603–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Falase AO, Salako LA. Clinical experience with Timolol maleate (Blocadren, MSD) in Nigerian hypertensives. Niger Med J. 1979;9:453–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Falase AO, Salako LA. beta-Adrenoceptor blockers in the treatment of hypertension. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1979;8:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Osuntokun BO, Akinkugbe FM, Francis TI, Reddy S, Osuntokun O, Taylor GO. Diabetes mellitus in Nigerians: a study of 832 patients. West Afr Med J Niger Pract. 1971;20:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Osuntokun BO. Hypertension in Nigerian diabetics: a study of 832 patients. Afr J Med Sci. 1972;3:257–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Osuntokun BO. Stroke in the Africans. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1977;6:39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Osuntokun BO, Bademosi O, Akinkugbe OO, Oyediran AB, Carlisle R. Incidence of stroke in an African City: results from the Stroke Registry at Ibadan, Nigeria, 1973-1975. Stroke. 1979;10:205–207. doi: 10.1161/01.str.10.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soyannwo MA, Ayeni O, Lucas AO. Studies on the prevalence of renal disease and hypertension in relation to schistosomiasis. IV. Systemic blood pressure hypertension and related features. Niger Med J. 1978;8:465–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soyannwo MA, Ayeni O, Lucas AO. Studies on the prevalence of renal disease and hypertension in relation to schistosomiasis: I Some aspects of epidemiological methods in the rural illiterate setting. Niger Med J. 1978;8:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Soyannwo MA, Lagundoye SB, Lucas AO. Studies on the prevalence of renal disease and hypertension in relation to schistosomiasis. V. Radiological findings: plain X-ray abdomen and intravenous pyelogram. Niger Med J. 1978;8:477–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Soyannwo MA, Lucas AO. Studies on the prevalence of renal disease and hypertension in relation to schistosomiasis II: Nocturia and day-time frequency of micturition in the rural community of Nigeria. Niger Med J. 1978;8:296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soyannwo MA, Ogbechi ME, Adeyeni GA, Soyeni AI, Lipede MR, Lucas AO. Studies on the prevalence of renal disease and hypertension in relation to schistosomiasis. III. Proteinuria, haematuria, pyuria and bacteriuria in the rural community of Nigeria. Niger Med J. 1978;8:451–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Monekosso GL. Clinical survey of a yoruba village. West Afr Med J. 1964;13:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ojo OA, Akinkugbe OO. Nontoxemic hypertension in pregnancy in the African indigene. An analysis of 30 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;105:938–941. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(69)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brockington IF. Postpartum hypertensive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1971;27:650–658. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(71)90231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carlisle R. Remission of hypertension in Nigerians. Clinical observations in twelve patients. Afr J Med Sci. 1971;2:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aderele WI, Seriki O. Hypertension in Nigerian children. Arch Dis Child. 1974;49:313–317. doi: 10.1136/adc.49.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Akinkugbe A. Arterial pressures in non-pregnant women of child-bearing age in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:545–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1976.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Etta KM, Watson RS. Casual blood pressures and their possible relation to age, body weight, Quetelet’s index, serum cholesterol, percentage of body fat and mid-arm muscle circumference in three groups of northern Nigerian residents. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1976;5:255–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olatunbosun DA, Bolodeoku JO, Cole TO, Adadevoh BK. Relationship of serum copper and zinc to human hypertension in Nigerians. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;53:134–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jain PS, Gera SC, Abengowe CU. Incidence of hypertension in Ahmadu Bello University Hospital Kaduna--Nigeria. J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;80:90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Olatunde A, Akinkugbe OO, Carlisle R. Beta-adrenergic blockers in the treatment of hypertension--experience with propranolol at Ibadan, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1977;54:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abdurrahman MB, Ochoga SA. Casual blood pressure in school children in Kaduna, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1978;30:325–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mabadeje AF. The use of low dose of chlorthalidone in hypertensive Nigerians. Niger Med J. 1979;9:755–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alakija W. A pilot study of blood pressure levels in Benin City, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1979;56:182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Abengowe CU, Jain JS, Siddique AK. Pattern of hypertension in the northern savanna of Nigeria. Trop Doct. 1980;10:3–8. doi: 10.1177/004947558001000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ladipo GO. Hypertensive retinopathy in Nigerians. A prospective clinical study of 350 cases. Trop Geogr Med. 1981;33:311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Twagirumukiza M, De Bacquer D, Kips JG, de Backer G, Stichele RV, Van Bortel LM. Current and projected prevalence of arterial hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa by sex, age and habitat: an estimate from population studies. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1243–1252. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328346995d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Omuemu VO, Okojie OH, Omuemu CE. Awareness of high blood pressure status, treatment and control in a rural community in Edo State. Niger J Clin Pract. 2007;10:208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ekwunife OI, Udeogaranya PO, Nwatu IL. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a Nigerian population. Health. 2010;7:731–735. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Osotimehin B, Lawal SO, Iyun AO, Falase AO, Pernollet MG, Devynck MA, Meyer P. Plasma levels of digitalis-like substance in Nigerians with essential hypertension. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1988;17:231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Osotimehin B, Erasmus RT, Iyun AO, Falase AO, Ahmad Z. Plasma renin activity and plasma aldosterone concentrations in untreated Nigerians with essential hypertension. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1984;13:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ogunlesi AO, Osotimehin B, Akinkugbe OO. Intracellular sodium and blood pressure in Nigerians. Ethn Dis. 1991;1:280–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aderounmu AF, Salako LA. Abnormal cation composition and transport in erythrocytes from hypertensive patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 1979;9:369–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1979.tb00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Obasohan AO, Osuji CO, Oforofuo IA. Sodium-lithium countertransport activity in normotensive offspring of hypertensive black Africans. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:373–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Adebiyi AA, Akinosun OM, Nwafor CE, Falase AO. Plasma catecholamines in Nigerians with primary hypertension. Ethn Dis. 2011;21:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Azinge EC, Sofola OA, Silva BO. Relationship between salt intake, salt-taste threshold and blood pressure in nigerians. West Afr J Med. 2011;30:373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ukoh VA, Ukoh GC, Okosun RE, Azubike E. Salt intake in first degree relations of hypertensive and normotensive Nigerians. East Afr Med J. 2004;81:524–528. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i10.9235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Elias SO, Azinge EC, Umoren GA, Jaja SI, Sofola OA. Salt-sensitivity in normotensive and hypertensive Nigerians. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2011;21:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Okoro EO, Uroghide GE, Jolayemi ET. Salt taste sensitivity and blood pressure in adolescent school children in southern Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1998;75:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Idahosa PE. Blood pressure pattern in urban Edos. J Hypertens Suppl. 1985;3:S379–S381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bunker CH, Ukoli FA, Nwankwo MU, Omene JA, Currier GW, Holifield-Kennedy L, Freeman DT, Vergis EN, Yeh LL, Kuller LH. Factors associated with hypertension in Nigerian civil servants. Prev Med. 1992;21:710–722. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90078-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, McGee D, Osotimehin B, Kadiri S, Muna W, Kingue S, Fraser H, Forrester T, et al. The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of west African origin. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:160–168. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Akinkugbe OO. The National Expert Committee. Non-Communicable Disease in Nigeria. Report of a National Survey. Series 4. Lagos: Intec Printers Limited; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kadiri S, Walker O, Salako BL, Akinkugbe O. Blood pressure, hypertension and correlates in urbanised workers in Ibadan, Nigeria: a revisit. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:23–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Onyemelukwe GC. National survey of non-communicable disease (NCD)- 2003 (South West Zone). On behalf of the Federal Minitry of Health NCD control programme, and the national expert committee on NCD in collaboration with the Nigeria Heart Foundation. 2003. Available from: http: //www.docstoc.com/docs/106751314/RESULTS. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Akinkugbe OO. Health behavior monitor among Nigerian adult population: a collaborative work of Nigerian Heart Foundation and Federal Ministry of Health and Social Services, Abuja supported by World Health Organization, Geneva. 2003. Available from: http: //www.who.int/chp/steps/2003_STEPS_Report_Nigeria.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Erhun WO, Olayiwola G, Agbani EO, Omotosho NS. Prevalence of Hypertension in a University Community in South West Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research. 2005;8:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oghagbon EK, Okesina AB, Biliaminu SA. Prevalence of hypertension and associated variables in paid workers in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ukoh VA. Admission of hypertensive patients at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2007;84:329–335. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i7.9588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hendriks ME, Wit FW, Roos MT, Brewster LM, Akande TM, de Beer IH, Mfinanga SG, Kahwa AM, Gatongi P, Van Rooy G, et al. Hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: cross-sectional surveys in four rural and urban communities. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Odugbemi TO, Onajole AT, Osibogun AO. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors amongst traders in an urban market in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2012;19:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ike SO. Prevalence of hypertension and its complications among medical admissions at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu (Study 2) Niger J Med. 2009;18:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Arodiwe EB, Ike SO, Nwokediuko SC. Case fatality among hypertension-related admissions in Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Onwuchekwa AC, Asekomeh EG, Iyagba AM, Onung SI. Medical mortality in the Accident and Emergency Unit of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Niger J Med. 2008;17:182–185. doi: 10.4314/njm.v17i2.37380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Onwuchekwa AC, Chinenye S. Clinical profile of hypertension at a University Teaching Hospital in Nigeria. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:511–516. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s10245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ansa VO, Ekott JU, Essien IO, Bassey EO. Seasonal variation in admission for heart failure, hypertension and stroke in Uyo, South-Eastern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2008;7:62–66. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Isezuo SA. Seasonal variation in hospitalisation for hypertension-related morbidities in Sokoto, north-western Nigeria. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2003;62:397–409. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v62i4.17583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kolo PM, Jibrin YB, Sanya EO, Alkali M, Peter Kio IB, Moronkola RK. Hypertension-related admissions and outcome in a tertiary hospital in northeast Nigeria. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:960546. doi: 10.1155/2012/960546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Oladapo OO, Salako L, Sadiq L, Shoyinka K, Adedapo K, Falase AO. Target-organ damage and cardiovascular complications in hypertensive Nigerian Yoruba adults: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23:379–384. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2012-021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ayodele OE, Alebiosu CO, Salako BL, Awoden OG, Abigun AD. Target organ damage and associated clinical conditions among Nigerians with treated hypertension. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2005;16:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dada A, Adebiyi AA, Aje A, Oladapo OO, Falase AO. Standard electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy in Nigerian hypertensives. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nkado RN, Onwubere BJ, Ikeh VO, Anisiuba BC. Correlation of electrocardiogram with echocardiographic left ventricular mass in adult Nigerians with systemic hypertension. West Afr J Med. 2003;22:246–249. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i3.27960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ogah OS, Adebiyi AA, Oladapo OO, Aje A, Ojji DB, Adebayo AK, Salako BL, Falase AO. Association between electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy with strain pattern and left ventricular structure and function. Cardiology. 2006;106:14–21. doi: 10.1159/000092478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Oyati IA, Danbauchi SS, Alhassan MA, Isa MS. Diastolic dysfunction in persons with hypertensive heart failure. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:968–973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ike S, Ikeh V. The prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in adult hypertensive nigerians. Ghana Med J. 2006;40:55–60. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v40i2.36018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Adebiyi AA, Aje A, Ogah OS, Ojji DB, Oladapo OO, Falase AO. Left ventricular diastolic function parameters in hypertensives. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:41–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Adamu GU, Katibi AI, Opadijo GO, Omotoso AB, Araoye AM. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in newly diagnosed Nigerians with systemic hypertension: a pulsed wave Doppler echocardiographic study. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10:177–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Akintunde AA, Familoni OB, Akinwusi PO, Opadijo OG. Relationship between left ventricular geometric pattern and systolic and diastolic function in treated Nigerian hypertensives. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21:21–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Adebayo AK, Oladapo OO, Adebiyi AA, Ogunleye OO, Ogah OS, Ojji DB, Adeoye MA, Ochulor KC, Enakpene EO, Falase AO. Characterisation of left ventricular function by tissue Doppler imaging technique in newly diagnosed, untreated hypertensive subjects. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2008;19:259–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Adebayo AK, Oladapo OO, Adebiyi AA, Ogunleye OO, Ogah OS, Ojji DB, Aje A, Adeoye MA, Ochulor KC, Enakpene EO, et al. Changes in left atrial dimension and function and left ventricular geometry in newly diagnosed untreated hypertensive subjects. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9:561–569. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f2197f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ogah OS, Akinyemi RO, Adegbite GD, Udofia OI, Udoh SB, Adesina JO, Ojo OS, Alabi AA, Majekodunmi T, Osinfade JK, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in hypertensive Nigerians: echocardiographic study of 832 subjects. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2011;22:297–302. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2010-063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Akintunde AA, Akinwusi PO, Opadijo GO. Relationship between Tei index of myocardial performance and left ventricular geometry in Nigerians with systemic hypertension. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2011;22:124–127. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2010-050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Adebiyi AA, Ogah OS, Aje A, Ojji DB, Adebayo AK, Oladapo OO, Falase AO. Echocardiographic partition values and prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive Nigerians. BMC Med Imaging. 2006;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ogah OS, Bamgboye AE. Correlates of left ventricular mass in hypertensive Nigerians: an echocardiographic study. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21:79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Karaye KM, Habib AG, Mohammed S, Rabiu M, Shehu MN. Assessment of right ventricular systolic function using tricuspid annular-plane systolic excursion in Nigerians with systemic hypertension. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21:186–190. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2010-031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Akintunde AA, Akinwusi PO, Familoni OB, Opadijo OG. Effect of systemic hypertension on right ventricular morphology and function: an echocardiographic study. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21:252–256. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2010-013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Okeahialam BN. The burden of arrhythmia in hypertension: an electrocardiographic study. Nig J Cardiol. 2004;1:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ojji DB, Alfa J, Ajayi SO, Mamven MH, Falase AO. Pattern of heart failure in Abuja, Nigeria: an echocardiographic study. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2009;20:349–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Onwuchekwa AC, Asekomeh GE. Pattern of heart failure in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:745–750. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Laabes EP, Thacher TD, Okeahialam BN. Risk factors for heart failure in adult Nigerians. Acta Cardiol. 2008;63:437–443. doi: 10.2143/AC.63.4.2033041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ogah OS, Falase AO, Carrington M, Stewart S, Sliwa K. Hypertensive heart failure in Nigerian Africans: insights from the Abeokuta heart failure registry. Circulation. 2012;125:e703. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Falase AO, Ogah OS. Cardiomyopathies and myocardial disorders in Africa: present status and the way forward. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012:In press. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2012-046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Lawal SO, Osotimehin BO, Falase AO. Mild hypertension in patients with suspected dilated cardiomyopathy: cause or consequence? Afr J Med Med Sci. 1988;17:101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Ogun SA, Ojini FI, Ogungbo B, Kolapo KO, Danesi MA. Stroke in south west Nigeria: a 10-year review. Stroke. 2005;36:1120–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166182.50840.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Danesi M, Okubadejo N, Ojini F. Prevalence of stroke in an urban, mixed-income community in Lagos, Nigeria. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;28:216–223. doi: 10.1159/000108114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]