Abstract

Objective

Define the impact of prolapse mesh on the biomechanical properties of the vagina by comparing the prototype Gynemesh PS (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) to 2 new generation lower stiffness meshes, SmartMesh (Coloplast, Minneapolis, MN) and UltraPro (Ethicon).

Design

A study employing a non-human primate model

Setting

University of Pittsburgh

Population

45 parous rhesus macaques

Methods

Meshes were implanted via sacrocolpexy after hysterectomy and compared to Sham. Because its stiffness is highly directional UltraPro was implanted in two directions: UltraPro Perpendicular (less stiff) and UltraPro Parallel (more stiff), with the indicated direction referring to the blue orientation lines. The mesh-vaginal complex (MVC) was excised en toto after 3 months.

Main Outcome Measures

Active mechanical properties were quantified as contractile force generated in the presence of 120 mM KCl. Passive mechanical properties (a tissues ability to resist an applied force) were measured using a multi-axial protocol.

Results

Vaginal contractility decreased 80% following implantation with the Gynemesh PS (p=0.001), 48% after SmartMesh (p=0.001), 68% after UltraPro parallel (p=0.001) and was highly variable after UltraPro perpendicular (p =0.16). The tissue contribution to the passive mechanical behavior of the MVC was drastically reduced for Gynemesh PS (p=0.003) but not SmartMesh (p=0.9) or UltraPro independent of the direction of implantation (p=0.68 and p=0.66, respectively).

Conclusions

Deterioration of the mechanical properties of the vagina was highest following implantation with the stiffest mesh, Gynemesh PS. Such a decrease associated with implantation of a device of increased stiffness is consistent with findings from other systems employing prostheses for support.

Keywords: polypropylene mesh, prolapse, biomechanical properties, tissue remodeling

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a prevalent condition that can have a substantial negative impact a woman’s daily living and quality of life. A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing surgery to repair POP is approximately 7% (1, 2). Of those women, an estimated 13% will require a repeat operation within 5 years, and as many as 29% will undergo another surgery for prolapse or a related condition at some point during their life (2, 3). To improve on the perceived poor anatomical outcomes of native tissue repairs, surgeons have turned to synthetic mesh augmented repairs. Of the estimated 300,000 women who underwent a surgical procedure to repair POP in 2010, 1/3 received mesh. (4). Level I evidence supports the use of synthetic mesh in abdominal sacrocolpopexy with lower rates of vaginal vault prolapse than sacrospinous colpopexy (5). For transvaginal procedures, mesh augmented repairs are superior to native tissue repairs when used in the anterior and apical compartments (5–8). However, in all studies to date, mesh procedures are associated with a higher rate of complications than native tissue repairs (6, 7). Common complications include exposure or extrusion of mesh into the vagina, erosion into an adjacent structure, infection and pain. Although these complications are associated with any procedure involving the use of mesh, they appear to be higher when mesh is implanted vaginally.

In 2008, the FDA issued a public health notification warning of serious complications associated with the use of synthetic meshes in transvaginal prolapse repairs. In 2011, a second notification was issued warning that these complications are not rare events and that several "contributing factors may include the overall health of the patient, the mesh material, and the size and shape of the mesh.” (4, 9).

Currently, the most widely used prolapse mesh is the prototype lightweight, knitted, wide-pored, polypropylene mesh, Gynemesh PS (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). However, since the advent of Gynemesh PS, numerous competitor meshes with similar textile properties but distinct pore sizes and knit patterns have also been introduced making it difficult to know if one mesh is more suitable for prolapse surgery than another (10–12). According to the companies, all light weight wide pore knitted polypropylene materials are similar; however, ex vivo biomechanical testing has demonstrated that this is not the case with the biomechanical behavior of these meshes being quite variable; particularly in regard to the critical biomechanical parameter of stiffness. The latter describes the ability of a material to resist deformation when pulled apart, and is most often utilized to make comparisons between devices in order to define differences in mechanical function. While a stiffer material may be superior in regards to its ability to maintain its structure under a variety of loading conditions, it is also more likely to be less compatible with the mechanical properties of the tissue it is replacing and in this way, has the potential to be associated with a higher rate of complications (13,14). The ideal material would have a stiffness that after incorporation into the host tissue would closely mimic that of the host tissue under ideal loading conditions (i.e. absence of disease or deterioration).

To date, few studies have thoroughly investigated the impact of synthetic meshes on the biomechanical properties of the vagina. The latter also known as “functional properties” are comprised primarily of an active and passive component, which are critical for maintaining healthy sexual function and providing structural integrity in the vagina’s central role in pelvic organ support. While active properties require energy to function and are mainly served by the smooth muscle component, the passive properties perform in the absence of any active force generation and are mainly provided by vaginal collagen, elastin and matrix proteins.

One could argue that based on the differences in the mechanical behavior (stiffness) of current prolapse meshes, their impact on the underlying and newly incorporated vaginal tissue is likely to differ following implantation. To determine the impact of meshes with variable mechanical attributes on the functional properties of the vagina, we implanted the higher stiffness prototype prolapse mesh (Gynemesh PS, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) following hysterectomy via sacrocolpopexy in the rhesus macaque and compared the host biomechanical response to that following implantation of two lower stiffness meshes SmartMesh (Coloplast, Minneapolis, MN) and UltraPro (also available as Prolift plus M, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). Since the mechanical behavior of UltraPro is highly dependent on the direction in which it loaded (15–17), we implanted it both perpendicular (less stiff) and parallel (more stiff) to its blue orientation lines (15, 17). We utilized the sacrocolpopexy procedure for implantation since it is currently the gold standard prolapse repair surgery, and it is important to clearly define the impact of mesh on the vagina using this method prior to defining how the host response to vaginal implantation is different. We chose to implant the mesh in parous non-human primate (NHP) animals with minimal prolapse as we aimed to understand the impact of the mesh on the “normal” vagina prior to understanding its effect on the structurally compromised prolapse tissue. The NHP is arguably the most relevant option for conducting controlled prolapse mesh implantation studies due to its size, semi–bipedal posture, and anatomical/physiological similarities to humans (18–19). Further, the rhesus macaque is an established model to study the vaginal tissue behavior because it has similar reproductive physiology to humans and spontaneously develops prolapse (18). Recent evidence has also demonstrated similarities in the biomechanical behavior of the vagina between parous women and rhesus macaques (18–20), making it an excellent model for studying the impact of mesh implantation on the vagina.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Meshes

Based on a previously developed uniaxial tensile testing protocol, the ex vivo stiffness of each mesh had been defined along the long axis according to the implantation direction on the vagina. Gynemesh PS, the prototype polypropylene mesh for prolapse repair, was used as the stiffest mesh (0.29 ± 0.015 N/mm). For comparison, we used two low stiffness meshes: SmartMesh without an absorbable component (0.18 ± 0.026 N/mm) and UltraPro with an absorbable component implanted in two directions (21). The least stiff orientation (perpendicular to the blue orientation lines) of UltraPro has a stiffness of 0.009 ± 0.0016 N/mm, while its higher stiffness orientation (parallel to the blue orientation lines) has a stiffness of 0.258 ± 0.085 N/mm (15, 21). Within this paper UltraPro perpendicular will refer to this less stiff orientation, while UltraPro parallel will indicate the more stiff direction. It should be noted that the Prolift+M kit which utilizes UltraPro was designed for the mesh to be implanted with the least stiff direction along the longitudinal axis of the vagina and the stiffest direction along the transverse axis.

Animals

Animals that were used in this study were maintained and treated according to experimental protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (IACUC #1008675) and in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the use of laboratory animals such that the absolute minimum number of rhesus macaques (macacca mulatta) were used to answer our research question. Animals were maintained in standard cages with ad libitum water and a scheduled monkey diet supplemented with fresh fruit, vegetables, and multiple vitamins daily. A 12-hour light/dark cycle (7 am to 7 pm) was used, and menstrual cycle patterns were recorded daily. Available demographic data of each NHP were collected prior to and after surgery including age, weight, gravidity, and parity. Researchers were blinded to all demographical data of each NHP until completion of the study.

Forty-five cycling parous animals (9 to 16 years old) that were a minimum of 12 months after their last delivery were randomized for sham operation (N = 11) or implantation with Gynemesh PS (N=9), SmartMesh (N=8), UltraPro Perpendicular (N=9), and UltraPro Parallel (n=8) following an abdominal hysterectomy with preservation of the ovaries via sacrocolpopexy. Following intubation, the animals received intravenous antibiotics (Gentamicin), were prepped and draped with a transurethral catheter sterilely placed. Briefly, a midline incision was made through the abdominal wall. A complete hysterectomy was performed without excision of the ovaries. First, dissection of the bladder off of the anterior vagina was performed until the level of the trigone and the rectum was dissected off of the posterior vagina to within 2 cm of the perineal body. At this point, the surgeon was handed a sterile piece of mesh or informed that the surgery was a sham surgery according to a previously determined randomization procedure with only the biotechnician unblinded to the identification of the mesh to be used for a particular animal. Two 3 cm wide by 10 cm long straps of mesh were laid flat on the anterior and posterior wall, respectively, and secured in place with a continuous suture (2-0 Biosyn™ Synovis, St. Paul, MN) along each lateral edge. The two straps of mesh were anchored into the sacral promonotory with two delayed absorbable sutures. Excess mesh was trimmed prior to closing the peritoneum over the mesh. The abdominal muscle layer was closed with a single continuous suture, while three to five interrupted sutures were used to re-approximate subcutaneous fat followed by a continuous subcutaneous closure (4-0 polysorb).

Three months following implantation, the vaginal mesh constructs were explanted. The vagina including the mesh stem attachment to the longitudinal ligament of the sacrum, the bladder, urethra and vaginal supportive tissues (paravaginal attachments to the pelvic sidewall and the pubococcygeous insertion onto the distal vagina) were excised en bloc using a trans-abdominal approach. The excised sample is referred to as the mesh-vagina complex (MVC). The equivalent tissues were excised in Sham operated animals. To minimize the number of animals used in this study, only one vaginal side (anterior or posterior) was utilized for each type of testing. The grafted anterior vaginal wall was utilized to assess contractility (active mechanical properties), while the entire grafted posterior vaginal wall was used to characterize the passive biomechanical properties via a ball burst test. All testing of the biomechanical outcomes were performed by individuals blinded to the aims of the study. In addition, the individuals performing the active mechanical assays were not aware of the results of the passive assays. However, because of the distinct differences in the appearance of the meshes, it was not possible to blind testers to mesh types.

Active Biomechanical Properties

Following removal from the host each sample was carefully cut into 1–2×6–10 mm2 circumferentially oriented strips, weighed and measured. A small portion of each specimen was retained for histomorphological analysis to confirm that full thickness vagina had been sampled. As we have previously shown that smooth viability progressively decreases 30 minutes after removal from the host (data not shown), only specimens that were properly positioned in the organ bath within 30 minutes of harvest were included in the analysis. The following numbers met criteria: Sham (n=8), Gynemesh PS (n=8), SmartMesh (n=8), UltraPro Perpendicular (n=6), and UltraPro Parallel (n=8). Two clips were used to secure each vaginal strip to the base of a biochamber and to a load cell (Honeywell, Morristown, NJ). Load response data was recorded in grams continuously. Strips were placed into a heated biochamber, bubbled by 95% air balanced with 5% CO2 in Krebs solution, to 37°C and subjected to a ~10 mN preload. Samples were then allowed to equilibrate for an hour before determining the maximum contractility of the sample after it was exposed to a 120 mM dose of potassium (K+). Each MVC was tested in duplicate and averaged together to obtain a single response from each specimen. The contractile force was converted to mN and normalized to tissue volume (mm3).

Passive Biomechanical Properties

To determine the passive biomechanical properties of the MVC, a custom designed scaled ball-burst apparatus was used. Samples for passive biomechanical analyses were obtained from the entire posterior vagina. Of the 45 posterior vaginal specimens, only a subset met the minimal criteria for biomechanical testing due to the required 25 mm by 25 mm specimen size to ensure complete clamping of the mesh during the ball-burst protocol: Sham (n=10), Gynemesh PS (n=8), SmartMesh (n=5), UltraPro Perpendicular (n=9), and UltraPro Parallel (n=8).

Tissue samples were wrapped in saline soaked gauze and stored at −20° C (22, 23). On the day of testing, the tissue was then placed into a scaled down version of the American Society for Testing of Materials (ASTM) standard ball-burst testing apparatus. For this protocol, the ASTM standard was scaled down by a factor of 2.67. We have previously validated that the stiffness results obtained using this apparatus are consistent with the ASTM standard apparatus (24). Samples were secured circumferentially along all edges with a sample diameter of 16.6 mm, and the base of the ball-burst fixture was placed onto the base of the materials testing machine (Instron5565 Industrial Products, Grove City, PA). After the specimen was in place, the ball, connected to the moveable crosshead in series with a 5 kN load cell (Instron, Canton, MA), was lowered to within 5 mm of the sample. The sample was then centered over the specimen using an x-y translation table. Throughout the protocol, the tissue moisture was maintained with a 0.9% saline solution. The sample was preloaded to 0.5 N and then the sample was loaded to failure. The crosshead was lowered at a continuous rate of 10 mm/min during this protocol. The resulting load (N) and elongation (mm) data were recorded to create the load-elongation curve for the mesh-vagina-complex or Sham tissue specimens. The same testing protocol was performed to determine the ex vivo structural properties of the Gynemesh PS, SmartMesh, and UltraPro prior to implantation. For ex vivo testing, each mesh group (n=5 per group) were loaded to failure following the similar protocol to generate the load-elongation curve representing the ex vivo mechanical behavior of each mesh.

From the load-elongation curve, we calculated the stiffness (N/mm), or resistance of the MVC or Sham tissue to deformation, by calculating the slope using a running window over 20% of the load-elongation curve, with the maximum slope being defined as the stiffness of the complex.

From overall biomechanical properties of the MVC, the independent contribution of the tissue associated with the MVC (underlying vagina and newly incorporated tissue) was calculated. To do this, the following assumptions were made: (1) the mesh and tissue represent parallel systems, (2) the mechanical properties of the mesh measured ex vivo do not change with time following implantation, and (3) the contribution of the tissue to the total stiffness of the MVC results from both the underlying grafted vagina and newly in-grown tissue, as well as their interaction with the mesh. These assumptions allowed us to then subtract the average ex vivo mesh stiffness from the total MVC stiffness to estimate the independent tissue contribution to the MVC stiffness using the formula:

ktissue = kMVC − kmesh

Where ktissue is the estimated tissue stiffness (i.e. that representing contributions from the tissue itself along with its interaction with the mesh), kMVC is the measured stiffness of the mesh-vagina complex, and kmesh is the ex vivo measured mesh stiffness determined from the ball-burst protocol.

Statistics

All statistical comparisons were made using SPSS (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Il. Version 18.0). As data were non-parametric, a Kruskal-Wallis test with a Mann-Whitney post hoc were performed for comparisons between each group. Correlations between the estimated tissue stiffness were made to the previously measured stiffness values obtained from uniaxial testing and the ball-burst protocol using a Spearman’s Rho test. All comparisons were made using a significance level of 0.05. Data are presented as median (interquartile range): where the interquartile range is defined as the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles.

Results

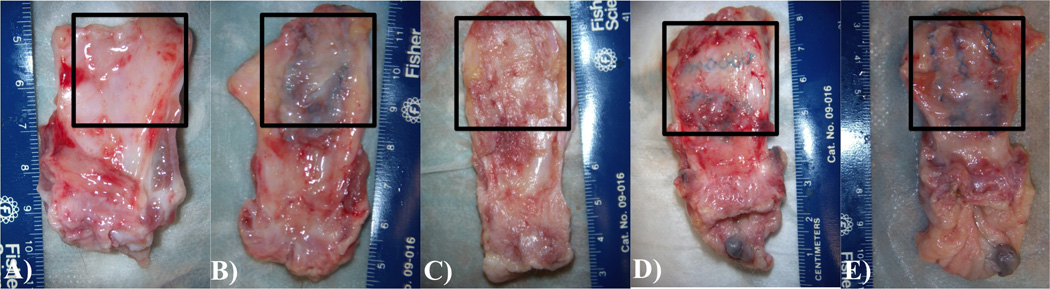

Demographic data from each NHP group are illustrated in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, weight, gravidity, or parity between groups. According to industry reported textile properties, UltraPro had the largest pore size at 4000 µm following degradation of the absorbable component, compared to Gynemesh PS (2440 µm) and SmartMesh (2370 µm). Gynemesh PS (42 g/m2) was the heaviest of these meshes followed by UltraPro, (28 g/m2 [post-absorption]) and the ultra-lightweight SmartMesh (19 g/m2). At the time of mesh explantation, there was better adherence and incorporation into the underlying tissue by the less stiff meshes (Figure 1). In contrast, although tissue had clearly grown into Gynemesh PS, it was qualitatively less dense. In addition, there were multiple areas of wrinkling in Gynemesh PS in spite of having been implanted flat. This was not the case with the other meshes, which maintained the flat conformation in which they had been implanted.

Table 1.

Demographical data of the Sham, Gynemesh PS, SmartMesh, UltraPro Perpendicular, and UltraPro Parallel NHPs groups. There were no significant differences observed in age, weight, gravidity, or parity in any the non-human primate groups. Data is represented as a median (interquartile range)

| Age (years) | Weight (kg) | Gravidity | Parity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n=11) | 14.5 (5.3) | 7.4 (2.9) | 3.5 (4) | 3.5 (4) |

| Gynemesh PS (n=9) | 13.0 (2.0) | 7.8 (2.4) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4 (3) |

| SmartMesh (n=8) | 13 (3.3) | 8.8 (2.7) | 5 (1.5) | 5 (2.3) |

| UltraPro Perpendicular (n=9) | 12 (3.5) | 6.4 (1.9) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3) |

| UltraPro Parallel (n=8) | 13 (0.5) | 8 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.8) | 4 (1.5) |

| Overall p-value | 0.6 | 0.13 | 0.3 | 0.47 |

Figure 1.

Examples of the explanted specimens after Sham surgery (A) vs implantation with Gynemesh PS (B), SmartMesh (C), UltraPro perpendicular (D), and UltraPro parallel (E). The grafted area of the vagina is indicated by the surrounding box. As evident from the image, SmartMesh and UltraPro healed in flat with thick tissue incorporated into the mesh, while Gynemesh PS was more likely to wrinkle and had a poor quality tissue incorporated into the mesh.

Active Biomechanical Properties: a measure of vaginal smooth muscle contractility

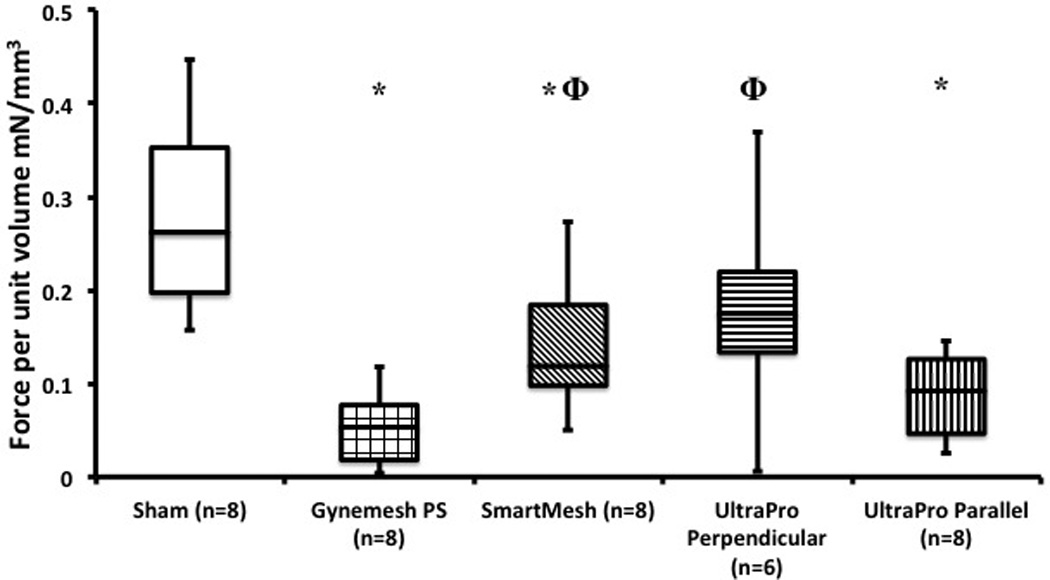

Overall, the KCl induced contractility of the MVC was negatively impacted following implantation with the three prolapse meshes (p<0.001, Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, Gynemesh PS had the greatest negative impact on vaginal contractility with a force generated that was 80% decreased relative to Sham (p=0.001). SmartMesh also had a significantly lower maximum force generated relative to Sham (48% decreased, p =0.016), but a higher force than that of Gynemesh PS (p =0.027). Following implantation with UltraPro perpendicular, vaginal contractility was highly variable [0.17 (0.21) mN/mm3] ranging from minimal response (0.006 mN/mm3) to a response that was not significantly different from Sham (0.37 mN/mm3, p=0.16). However, contractility of the MVC in the UltraPro perpendicular group was still found to be higher than that of Gynemesh PS implanted animals (p=0.02). In contrast, UltraPro parallel displayed no statistical difference to the Gynemesh PS (p=0.14), with a contractile force that was 68% below the level of Sham (p=0.001).

Figure 2.

Box plot of active biomechanical assays comparing Sham to mesh implanted animals. Contractile force, or force per volume (mN/mm3) is shown on the y-axis and is represented as median (interquartile range). Significant difference from sham indicated by (*), while Φ illustrates significant difference from Gynemesh PS.

Passive Biomechanical Properties: a measure of the structural components in the tissue such as collagen and elastin that allow a tissue to resist deformation when subjected to a force

Mesh-Vagina Tissue Complex

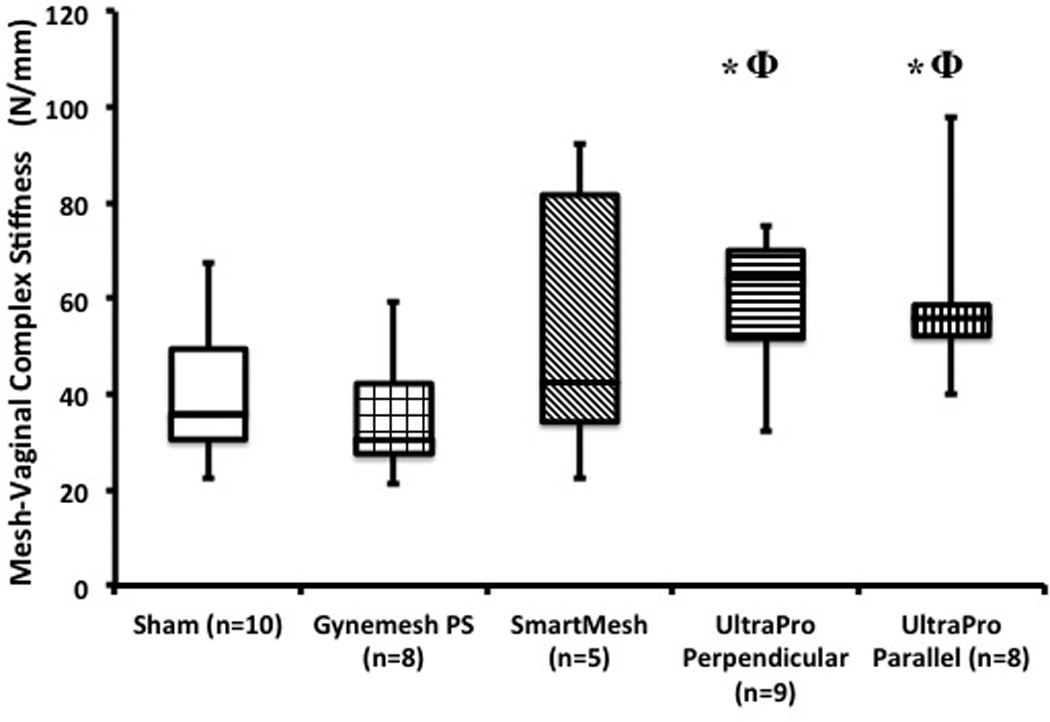

For the second aim of our study, we examined the passive biomechanical properties of Sham and MVC after implantation with Gynemesh PS, SmartMesh, and UltraPro. When comparing the stiffness of the overall MVC using the ball-burst test following implantation with mesh, we found significant differences relative to Sham (p=0.01, Figure 3). UltraPro implanted in the Perpendicular and Parallel direction were both found to be higher compared to Sham animals (p=0.016 and p=0.021, respectively). However, no differences were found between Sham and Gynemesh PS (p=0.53) and SmartMesh (p=0.46) implanted groups. In contrast to the contractility studies, UltraPro Perpendicular and UltraPro Parallel displayed remarkably close behavior with a 48% and 46% increase in stiffness relative to Sham (p = 0.03 and p=0.02, respectively). As illustrated in Figure 3, MVCs containing UltraPro in the perpendicular and parallel orientation were stiffer than those containing Gynemesh PS (p=0.01 and p=0.02, respectively).

Figure 3.

The stiffness of the mesh-vagina complex (MVC) relative to sham following implantation with three prolapse meshes - Gynemesh PS, SmartMesh, and UltraPro (perpendicular and parallel orientations). Significance from sham indicated by (*), while Φ illustrates significant difference from Gynemesh PS.

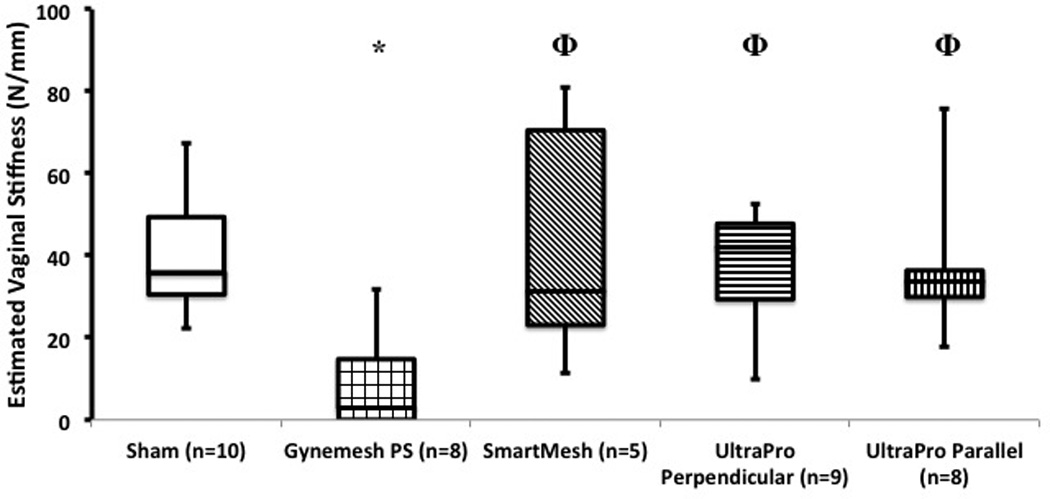

Estimated Tissue Contribution to the Overall Biomechanical Behavior of the MVC

Ideally, a prolapse mesh would enhance the properties of the structurally impaired vaginal tissue or at least allow its mechanical integrity to be maintained. We therefore asked, “What is the independent contribution of the associated vaginal tissue (vagina underlying graft plus the newly incorporated tissue) to the overall behavior (passive biomechanical properties) of the MVC? To estimate the vaginal tissue contribution to the overall stiffness of the MVC (i.e. its ability to resist deformation under an applied load), we subtracted the stiffness of each mesh (measured ex vivo prior to implantation) from the total MVC stiffness as described in the methods. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 4, we found that the biomechanical properties of the tissue associated with stiffest mesh, Gynemesh PS, were drastically reduced relative to those of Sham (p=0.003). In contrast, the tissue contribution of the vagina associated with Smartmesh (p=0.9), UltraPro perpendicular (p=0.68), and UltraPro parallel (p=0.66) were not significantly different to Sham. The biomechanical behavior of the Gynemesh PS MVC was largely determined by the mesh alone, as there was only a small contribution (24%) by the associated vaginal tissue due to its poor mechanical integrity. In contrast, the estimated contribution of the associated vaginal tissue was considerably higher for the other meshes accounting for 80%, 62%, and 62% of the total MVC stiffness following implantation with SmartMesh, UltraPro Perpendicular, and UltraPro Parallel, respectively. Thus, the mechanical integrity of the tissue associated with these meshes was substantially higher than that associated with Gynemesh PS.

Figure 4.

The estimated tissue stiffness of the associated vagina (underlying mesh and newly incorporated into mesh) following implantation with three prolapse meshes - Gynemesh PS, SmartMesh, and UltraPro (perpendicular and parallel orientations). Significance from Sham indicated by *, while Φ illustrates significant difference from Gynemesh PS.

Correlation of mesh properties biomechanical behavior of the MVC

We then performed an analysis to define the specific properties of mesh measured ex vivo (prior to implantation) that correlated with either the biomechanical behavior of the overall MVC or the independent behavior of the associated vagina. From this analysis, we found that the force generated by the smooth muscle (active mechanical properties) negatively correlated with the specific weight of the mesh (R= −0.422, p=0.02) and the ex vivo mesh stiffness measured via a uniaxial (R=−0.563, p=0.001) and ball-burst test (R= −0.422, p=0.02).

The estimated independent biomechanical behavior of the tissue associated with the MVC negatively correlated with weight (R= −0.534, p =0.002) and the ex vivo mesh stiffness measured from the uniaxial and ball-burst tests (R=−0.514, p=0.004 and R= −0.534, p =0.002, respectively). Accordingly, a less stiff mesh would be more likely than a stiffer mesh to maintain the native biomechanical properties of the vaginal tissue.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the impact of 3 prolapse meshes with varying biomechanical behavior - Gynemesh PS, SmartMesh, and UltraPro, on the active and passive biomechanical properties of the vagina following sacrocolpopexy utilizing a nonhuman primate model. In previous studies, these meshes were found to have variable stiffness values in response to uniaxial tension in descending order with Gynemesh PS > UltraPro parallel > Smartmesh > UltraPro perpendicular. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the impact of these prolapse meshes on the active and passive biomechanical properties of the vagina in vivo. The evidence within this paper illustrates that all meshes used in this study significantly negatively impacted the vaginal biomechanical properties of the underlying and incorporated vagina but the degree of negative impact correlated with the weight and stiffness of the implanted mesh. Indeed the prototype mesh, Gynemesh PS, the stiffest, heaviest mesh implanted in this study, had the greatest negative impact on both vaginal contractile (active) and passive biomechanical properties following implantation.

As the FDA places stricter warnings on the use of mesh and notes that the mesh material implanted may be affecting the host response and contributing to the current complication rate, the findings of this study are indeed timely. Studies of other prosthetic devices indicate that the stiffness of a material is directly linked to its complications; primarily due to a phenomenon that occurs when two solid materials are connected, referred to as “stress shielding” (13, 14). According to this perspective, following implantation, the stiffer material buffers or “shields” the adjacent tissue from experiencing the physiological loads (forces) that it normally is exposed to. In the absence of loading, the less stiff tissue degenerates.

Stress shielding has been shown to occur in a wide variety of physiological conditions in both hard and soft tissues (13, 14). The most recognizable example of stress shielding occurs with casting of a fractured extremity. Once the cast is placed, the affected extremity is exposed to an extended period of immobility resulting in atrophy, including a loss of bone density and muscle mass (25). Here, we propose that stress-shielding may also play an important role in defining the impact of a prolapse mesh on the vagina since placement of a mesh on the external surface of the vagina would lessen the degree of deformation the vagina normally undergoes in response to daily physiologic loads (standing, walking, coughing etc). As the stiffness of a mesh increases, the negative impact of stress shielding would likewise increase. Indeed, following the placement of a high stiffness mesh, one could envision that thinning of the underlying vagina due to stress shielding would lead to an increased rate of mesh exposures and erosions. Thus, the movement over the past several decades toward lower weight less stiff meshes may be justified.

While the theory of stress shielding may help to improve our understanding of the impact of mesh on the vagina, it is only one of multiple possible mechanisms that could affect the active and passive properties of the vaginal tissue after mesh implantation. Other factors that could play a fundamental role include surgical technique, the host foreign body response, the host environment (obesity, diabetes, smoking) and genetic factors.

We chose to implant UltraPro in two perpendicular orientations due to the highly anisotropic behavior of this mesh. Anisotropy refers to a material that behaves very differently biomechanically according to the direction it is loaded. Interestingly, while the direction of implantation greatly influenced active smooth muscle contractility, passive mechanical behavior was not affected. When UltraPro was implanted perpendicular (less stiff) direction, the response of the smooth muscle varied widely suggesting that additional factors influenced smooth muscle contractility in this orientation. On the other hand, implantation of UltraPro in its stiffer direction (parallel) diminished smooth muscle contractility to a level equivalent to that of Gynemesh PS.

The profound negative impact of stiffer meshes such as Gynemesh PS and UltrPro parallel on vaginal smooth muscle function is a phenomenon worth pursuing. It could be argued that the following the placement of a stiffer mesh, the smooth muscle cells are capable of actively contracting, but simply cannot generate a force big enough to overcome the stiffness of the mesh and therefore, give the appearance of having diminished contractility. Alternatively, the smooth muscle of the vagina associated with the graft may degenerate due to stress shielding or a chronic inflammatory response such that the decreased contractility reflects loss of smooth muscle volume (thinner muscularis). In either case, given the evidence that vaginal smooth muscle is already compromised in women with prolapse (26), a further decline in smooth muscle function imposed by a prolapse mesh is not a desirable endpoint. Future research should focus on the development of graft materials that restore rather than compromise smooth muscle function.

In contrast to the active mechanical studies, we found that the direction of implantation of UltraPro had no impact on the results of our mechanical assays. This may be due to the biomechanical test we chose to evaluate the MVC after implantation. Here, we examined the passive properties via a ball-burst test, which secures the MVC circumferentially regardless of implantation direction, and therefore, may limit our ability to detect differences in the impact of this highly anisotropic mesh on the vagina. We may have a better means to detect these changes if we tested the axes of the vagina separately: via a uniaxial or bi-directional test. For example, if the smooth muscle, collagen and elastin of the associated vagina reorganized differently according to the direction UltrPro was implanted, this would be observed in the uniaxial contractile test, but not in the multi-axial ball burst test. Alternatively, the fact that tissues obtained for passive biomechanical testing were always from the posterior vagina and those evaluated for active biomechanical testing were from the anterior vagina could be playing a role. Arguably, the mechanical burden on the anterior vagina is higher than the posterior making it more sensitive to differences related to the anisotropy of UltraPro. Future work will aim to evaluate the passive mechanics of the anterior wall following implantation of UltraPro in its parallel and perpendicular directions.

While the strengths of the study include the use of a highly relevant animal model to provide mechanistic insight into the impact of mesh on the vagina, the relatively high number of animals employed and the biomechanical endpoints used to evaluate vaginal tissue integrity, the study also has limitations. First, our mathematical model provides an approximation of vaginal tissue properties on a macroscale. While the estimated tissue stiffness calculation that we are reporting includes the tissue’s interaction with the mesh, we are unable to tease out the individual contributions of the underlying tissue versus the tissue that has integrated into the mesh and their interaction with the mesh. We also assume that the mesh properties do not significantly change with time, which may not actually be the case for these prolapse meshes. However, previous research utilizing the abdominal wall animal model has confirmed that this assumption holds, at least for the time period of implantation that we investigated (27, 28). In the future we aim to develop mathematical models to account for these assumptions and provide detailed information of the local stress and strains experienced by vaginal tissue following mesh implantation.

Although the current study provides valuable mechanistic data, it is based on a limited number of animals and meshes. However, from our correlation analysis it suggests that higher weight and stiffer polypropylene meshes inhibit the contractility of the smooth muscle within the vaginal wall. This information may be useful when designing future large multi-site clinical trials, which are needed to test whether mesh related complications, including those incurred following a sacrocolopexy can be reduced by moving toward a lower weight lower stiffness mesh without compromising anatomical outcomes.

In summary, this study examined the in vivo functional properties of grafted vaginal tissue following implantation with three synthetic prolapse meshes. The active and passive properties of the vagina were significantly affected after mesh implantation and were consistent with a stress-shielding response, which may impair the ability of the vagina to normally function. This phenomenon was particularly evident while examining the stiffest mesh (Gynemesh PS) compared to SmartMesh, UltraPro Perpendicular, and UltraPro Parallel. Further studies of additional meshes with a different range of textile properties (e.g. porosity and specific weight) and biomechnical properties (e.g. stiffness) will help us determine which individual or combination of properties can avert this stress-shielding response and lead to improved tissue incorporation/function after implantation.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Financial contribution provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Support R01 HD061811-01.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interests

The authors have no disclosers

Contribution of Authorship

SA and PM planned and developed the study. PM, AF, SS, SP, WB, and SA performed the implantations, while AF, SS, and SP performed the explantations. AF, ZJ, and WB performed data collection and analysis. AF was the primary author of the manuscript, and all authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Details of Ethical Approval

This study was conducted with the approval of the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Animal Care Use Committee (IACUC #1008675) and in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines (approval date August 6th, 2010)

Contributor Information

Andrew Feola, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Musculoskeletal Research Center, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh

Steven Abramowitch, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Musculoskeletal Research Center and Magee-Womens Research Institute, Departments of Bioengineering and Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Pittsburgh

Zegbeh Jallah, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Musculoskeletal Research Center, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh

Suzan Stein, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Magee-Womens Research Institute, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Pittsburgh

William Barone, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Musculoskeletal Research Center, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh

Stacy Palcsey, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Magee-Womens Research Institute, Department Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Pittsburgh

Pamela Moalli, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Magee-Womens Hospital, Magee-Womens Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh

References

- 1.Subak LL, Waetjen LE, Eeden SVD, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:646–651. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen AL, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark AL, et al. Epidemiologic evaluation of reoperation for surgically treated pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1261–1267. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00829-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.F.a. D. Administration E, editor. FDA. Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh: Update on the Safety and Effectiveness of Transvaginal Placement for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher CM. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: the updated summary version Cochrane review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(11):1445–1457. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman D, et al. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1826–1836. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feiner B, Jelovsek JE, Maher C. Efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh kits in the treatment of prolapse of the vaginal apex: a systematic review. Bjog. 2009;116:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diwadkar GB, et al. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):367–373. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195888d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. F.a. D. Administration E, editor. Public Health Notification: Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh in Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz HP, Vancaillie P, Svehla M, Walsh W, Steensma AB, Vancaillie TG. Mechanical properties of urogynecologic implant materials. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003 Oct;14(4):239–243. doi: 10.1007/s00192-003-1041-8. discussion 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones KA, Feola A, Meyn L, Abramowitch SD, Moalli PA. Tensile properties of commonly used prolapse meshes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009 Jul;20(7):847–853. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0781-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulliam SJ, Ferzandi TR, Hota LS, Elkadry EA, Rosenblatt PL. Use of synthetic mesh in pelvic reconstructive surgery: a survey of attitudes and practice patterns of urogynecologists. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007 Dec;18(12):1405–1408. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majima T, Yasuda K, Tsuchida T, Tanaka K, Miyakawa K, Minami A, et al. Stress shielding of patellar tendon: effect on small-diameter collagen fibrils in a rabbit model. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(6):836–841. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0707-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagels J, Stokdijk M, Rozing PM. Stress shielding and bone resorption in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003 Jan-Feb;12(1):35–39. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feola A, Pal S, Moalli P, Maiti S, Abramowitch S, editors. American Society of Mechanical Engineers Summer Bioengineering Conference. Fajardo, Puerto Rico: 2012. Varying Degrees of Nonlinear Mechanical Behavior Arising From Geometric Differences of Urogynecological Meshes. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozog Y, Konstantinovic M, Werbrouck E, De Ridder D, Mazza E, Deprest J. Persistence of polypropylene mesh anisotropy after implantation: an experimental study. Bjog. 2011 Sep;118(10):1180–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03018.x. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saberski ER, Orenstein SB, Novitsky YW. Anisotropic evaluation of synthetic surgical meshes. Hernia. 2011 Feb;15(1):47–52. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0731-7. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abramowitch SD, Feola A, Jallah Z, Moalli PA. Tissue mechanics, animal models, and pelvic organ prolapse: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009 May;144(Suppl 1):S146–S158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feola A, Abramowitch S, Jones K, Stein S, Moalli P. Parity negatively impacts vaginal mechanical properties and collagen structure in rhesus macaques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Dec;203(6):595, e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei L, Song Y, Chen R. Biomechanical properties of prolapsed vaginal tissue in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007 Jun;18(6):603–607. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepherd J, Feola AJ, Stein S, Moalli P, Abramowitch SD. Uniaxial Biomechanical Properties of 7 Different Vaginally Implanted Meshes for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. International Urogyn J. 2012;23(5):613–620. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1616-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubod C, Boukerrou M, Brieu M, Dubois P, Cosson M. Biomechanical properties of vaginal tissue. Part 1: new experimental protocol. J Urol. 2007 Jul;178(1):320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.040. discussion 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woo SL, Orlando CA, Camp JF, Akeson WH. Effects of postmortem storage by freezing on ligament tensile behavior. J Biomech. 1986;19(5):399–404. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(86)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feola AJ, Barone WR, Shepherd J, Moalli P, Abramowitch S. American Society of Mechanical Engineers Summer Bioengineering Conference. Farmington, PA: 2011. Jun 22–25, Characterization of the Ex-Vivo Properties of Prolapse Meshes. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woo SL, Gomez MA, Sites TJ, Newton PO, Orlando CA, Akeson WH. The biomechanical and morphological changes in the medial collateral ligament of the rabbit after immobilization and remobilization. J Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1987 Oct;69(8):1200–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boreham MK, Wai CY, Miller RT, Schaffer JI, Word RA. Morphometric analysis of smooth muscle in the anterior vaginal wall of women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jul;187(1):56–63. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.124843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cobb WS, Burns JM, Peindl RD, Carbonell AM, Matthews BD, Kercher KW, et al. Textile analysis of heavy weight, mid-weight, and light weight polypropylene mesh in a porcine ventral hernia model. J Surg Res. 2006 Nov;136(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klinge U, Junge K, Stumpf M, Ap AP, Klosterhalfen B. Functional and morphological evaluation of a low-weight, monofilament polypropylene mesh for hernia repair. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63(2):129–136. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]