Abstract

Tissue-engineering techniques have brought a great hope for bladder repair and reconstruction. The crucial requirements of a tissue-engineered bladder are bladder smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization. In this study, partial rabbit bladder (4×5 cm) was removed and replaced with a porcine bladder acellular matrix (BAM) that was equal in size. BAM was incorporated with platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the experimental group while with no bioactive factors in the control group. The bladder tissue strip contractility in the experimental rabbits was better than that in the control ones postoperation. Histological evaluation revealed that smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization in the experimental group were significantly improved compared with those in the control group (p<0.05), while multilayered urothelium was formed in both groups. Muscle strip contractility of neobladder in the experimental group exhibited significantly better than that in the control (p<0.05) assessed with electrical field stimulation and carbachol interference. The activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9 in the native bladder tissue around tissue-engineered neobladder in the experimental group was significantly higher than that in the control (p<0.05). This work suggests that smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization in tissue-engineered neobladder and recovery of bladder function could be enhanced by PDGF-BB and VEGF incorporated within BAM, which promoted the upregulation of the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 of native bladder tissue around the tissue-engineered neobladder.

Introduction

Congenital abnormalities, trauma, inflammation, and cancer often result in urinary bladder damage or loss, so bladder reconstruction is necessary. Currently, the common techniques of urinary bladder reconstruction with gastrointestinal segments are associated with various complications such as mucus production, chronic bacteriuria, stone formation, leakage and ruptures, fibrosis, electrolyte imbalance, and possible development of malignancy.1,2 Due to the problems in the use of gastrointestinal segments, numerous investigators have attempted the application of alternative materials and tissues for bladder reconstruction.

The bladder acellular matrix (BAM) derived from porcine is a frequently used biomaterial with the compositional and structural characteristics similar to native urinary extracellular matrix. Meanwhile, it is reported that BAM preserves some bioactive factors that may promote the healing effect observed.3,4 Studies indicate that BAM is a suitable scaffold that can promote functional regeneration of urinary bladder in porcine and dog models.5,6 However, in the regenerated tissues, smooth muscle regeneration and vessel formation are unsatisfied. As is known, bioactive factors have very important signal and regulatory functions in the development, maintenance, and regeneration of bladder tissues. However, the amount of these bioactive factors preserved in the BAM may be finite. Furthermore, they may be inactivated through the process of cell extraction and long-term preservation.7,8 Therefore, lack of them in BAM might lead to the limitation of smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization. Exogenous delivery of bioactive factors, which could make up the deficiency of endogenous bioactive factors, plays a crucial role in tissue engineering and regeneration.9 It is considered to be one of the critical elements for bladder regeneration.10

It has been reported that platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) is a physiologically relevant stimulator of mitogenic signaling in urinary tract smooth muscle cell.11 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as a kind of bioactive factor that promotes endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis,12 has been shown to enhance bladder regeneration only at early periods after grafting of BAM in rats.13 In our previous study, we have developed a porcine BAM with well-preserved extracellular bioactive factors, such as PDGF-BB and VEGF. Besides, sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) was also well preserved in our porcine BAM.14 The sulfated GAG in the BAM was used as a reservoir for delivering exogenous bioactive factors to improve bladder regeneration and vascularization in previous studies.13,15,16 In addition, there is a little affinity existing between collagen fibers and bioactive factors.17,18 Therefore, the porcine BAM we prepared would be a favorable scaffold for delivering exogenous bioactive factors to facilitate tissue engineering bladder regeneration.

It is reported that bioactive factors incorporated into BAM can enhance bladder regeneration by functional and histological examination.13,15,19 However, the mechanism of bioactive factors promoting bladder tissue regeneration is not completely characterized. In this study, we used porcine BAM that was incorporated with PDGF-BB and VEGF to repair partial excision bladder. Then, regenerated neobladder derived from BAM was investigated by histological and functional evaluation. In addition, the possible mechanism of histological regeneration was discussed.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of BAM

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of the Nanjing University School of Medicine. Whole bladders were obtained from 2-month-old house pigs weighing 22–25 kg, which had been used in other animal experiments. The bladder samples were immediately transported in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2–7.4) to the laboratory within minutes.

BAM was prepared as the protocols published by our team.14 Briefly, fat tissues and fascia on the serious side of the bladder lumen were removed. The bladder lumen was infused with about 100 mL 0.25% trypsin/0.038% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Gibco) through a catheter fixed at the bladder neck, and incubated in the same solution for 2 h at room temperature (RT). After washed thrice with ice-cold PBS, the bladder was distended with up to 300 mL wash buffer and fully immersed in the same solution, and then incubated overnight in an ice-cold hypotonic solution consisting of 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA (Amersco), and 10 KIU/mL Aprotinin (Livzon Pharmaceutical Group, Inc.). Another three washes with ice-cold PBS was performed, and the bladder was incubated in a hypertonic solution containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1.0% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 10 KIU/mL Aprotinin for 24 h at RT. Then, the bladder was washed thrice with ice-cold PBS, incubated with 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.6) containing 50 U/mL DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 U/mL RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 150 mM NaCl for another 24 h with simultaneous mechanical agitation on an orbital shaker (150 rpm; Gesellschaft Fur Labortechnik; Germany) to facilitate cell removal. After three washes with sterile ice-cold PBS to remove the residual reagents, the decellularized tissue was washed thrice with double-distilled water and was frozen, lyophilized in a FreeZone 4.5 Liter Freeze Dry System (Labconco), sterilized in ethylene oxide gas, and sealed at −20°C until use. The complete elimination of cellular nuclei in the BAM was confirmed by histological evaluation.14

Animals

A total of 24 male New Zealand white rabbits weighing 2.5–3.0 kg were used in this study. The investigation conformed to the Institutional and National Guidelines for Laboratory Animals. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of the Nanjing University School of Medicine. The rabbits were divided into two groups. Twelve of them received partial bladder replacement with porcine BAM combined with PDGF-BB and VEGF as a experimental group, and the other 12 received surgery only with porcine BAM as a control group. Animals of each group were sacrificed at 1 (n=3), 2 (n=3), 3 (n=3), and 6 (n=3) months postoperatively.

Surgical technique

Before the surgery, the rabbits were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and droperidol (2.5 mg/kg) intramuscularly. The maintenance of anesthesia with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and droperidol (2.5 mg/kg) incorporated into 100 mL sterile normal sodium was provided intravenously throughout the surgical procedure. The rabbits were shaved, cleaned, and draped in a sterile manner. Through a midline lower abdominal incision, the bladder was exposed and dissected freely. The bladder was filled with 70–80 mL of sterile physiological saline via urethral catheter. About 30–40% of bladder at size of 4×5 cm was removed, avoiding injury to the ureters and trigone. In the experimental group, the BAM patch that was in the same size with removed bladder tissue was rehydrated with 1 mL PBS containing 2 μg PDGF-BB and 2 μg VEGF, incubated at 37°C for 12 h13,15 and firmly anastomosed to the bladder using absorbable chorda chirurgicalis-interrupted suture. In the control group, the BAM patch was only rehydrated with PBS. After making sure that no urine leakage was found, the abdominal wall and skin were then closed in two layers with nonabsorbable 4/0 Prolene or nylon sutures without using any drainage. Penicillin (40 MU bid intramuscularly) was administered postoperatively for 3 days. All the rabbits were housed in hutch within a dedicated facility with well feeding. Appetite, mental status, and defecation of the rabbits were observed postoperatively.

Urodynamic studies

Urodynamic studies were performed preoperation and 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery, respectively, as described previously.20 The animal was catheterized using a 7F double-lumen transurethral catheter. Another side of catheter was connected to a simple pressure-monitoring device. After removing bladder residual urine, intravesical pressure was measured in the instillation of prewarmed sterile saline at constant rates. When fluid leakage was observed around the catheter, leak point pressure (LPP) was recorded. The volume of instilled saline was recorded as bladder capacity. Bladder compliance was calculated by dividing the bladder capacity by LPP.

Muscle tissue contractility

Retrieved bladder tissues from animals at 6 months were adopted for contractility test as previously reported.21,22 Native normal bladder tissue retrieved from animals with no-operation was used for normal control. After the retrieve, all the bladders were immediately placed in an ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) and opened along the lateral edges. The substitutional area was divided into the central and marginal zones, which were evaluated, respectively. A 2×10 mm (full-thickness) strip of neobladder tissue was dissected. Then, the strip was fixed with a microtissue holder in organ baths (Chengdu Instrument) containing the Krebs-Henseleit buffer at 37°C, bubbled with 95% O2 plus 5% CO2, and connected to force displacement transducers. Coupled with an isometric force transducer, the strips were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min. The strips were washed every 15 min, preadjusted to 0.6 g tension, and stimulated by an electrical field or drug. Electrical field stimulation was applied with the parameters consisting of 15 V, 2 ms in duration, 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, and 110 Hz frequency, and 2-min interval between 15-s stimulation. The contraction was recorded for 1 min. The same strip was equilibrated in 10 mL fresh Krebs-Henseleit buffer for 5 min to receive drug stimulation. Carbachol was added by using a 10- or 100-μL microsyringe (Eppendorf) near the oxygen bubbler to the final concentration of 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM, and 1 mM. The evoked construction was monitored for 2 min. The Krebs-Henseleit buffer was changed until the strip was equilibrated. Then, next concentration was detected. Each specimen was subjected to only one series of electrical field stimulation, followed by administration of the drug to minimize the artifacts related to tissue exhaustion or drug interference.

Histological evaluation

Bladder specimens were retrieved from rabbits sacrificed at each time point after surgery. The marginal zone and central zone of bladder specimens were separated to examination, respectively. Specimens that were not assessed for muscle tissue contractility were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were cut at 6 μm for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. In immunohistochemical staining, sections were deparaffinized, blocked, and incubated at 4°C overnight with alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibodies specific to smooth muscle and cell proliferation, respectively. Subsequent reaction was done by using the Dako Real™ EnVision™ Detection System, peroxidase/3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride, and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Bladder tissue obtained from rabbit without operation served as the normal control. Immunofluorescent double staining was performed by using the central-zone tissue of the neobladder in the experimental group at 2 months as followed. Frozen tissue sections (6 μm) were blocked, incubated with α-SMA at 4°C overnight, followed by being stained with IgG Alexa Fluor 633, and then incubated with PCNA at 4°C overnight, followed by being stained with IgG Alexa Fluor 488. At last, the cellular nucleus was detected by 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining.

Microvessel density (MVD) and microvessel area (MVA) were evaluated by calculating the number of luminal structures and the proportion of the area of luminal structures in the total area, respectively, with HE stains.23 Proliferative cell count (PCC) was evaluated by a semiquantitative analysis to count the proliferated cells, while ratio of proliferative cells (RPC) was to calculate the proportion of proliferative cells in total cells in immunohistochemical staining with PCNA.

Geletin zymography

Bladder specimens from native bladder adjacent substitutional area at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months postoperation and native bladder preoperation (normal control) were retrieved. Total protein was extracted from the retrieved bladder specimens with an RIPA lysis buffer without EDTA (10 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% Triton X-100, and 1% deoxycholate). Gelatinase activity in the extracted total protein was measured by gelatin zymography. Semiquantitative estimation of the activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9 has been completed through this procedure. Equal amounts of total protein (10 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis with SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel containing 0.1% gelatin. Gels were washed twice (30 min each) with a renaturing buffer (2.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.05% NaN3, 0.0028% ZnCl2, and 5 mM CaCl2) under constant mechanical stirring at RT. The gels were then immersed in a developing buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.05% NaN3, 0.0028% ZnCl2, and 5 mM CaCl2) and incubated at 37°C for at least 36 h. After being incubated, gels were stained with Coomassie blue R-250 for 1 h. All gels were calibrated with sea-blue molecular-weight marker and scanned to make a permanent record of the results. Relative concentrations were assessed by densitometric analysis of digitized autographic images, using the public domain Quantity One software. Activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was documented with the ratio of relative concentrations in native bladder postoperation to that in native bladder preoperation.

Statistical analysis

The comparisons between control and experimental group were statistically analyzed by the independent Student's t-test. The relationships between groups were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. When ANOVA indicated a significant difference, groups were further compared by using the least significant difference test. Results are expressed as p-values with p<0.05 representing statistically significant. All data are presented as mean±standard error.

Results

Macroscopic findings

Of the initial 24 operated rabbits, two died before their intended study period, including one in the 1-month and one in 6-month group of control. The reasons of death were urinary leakage and stone formation. The remaining 22 animals survived their scheduled sampling time with good appetite and well-mental status. All these animals could void spontaneously without a catheter. Gross hematuria was found in the first 2 or 3 days after surgery and subsequently disappeared. Gross examination of the bladders from both groups revealed mild adhesions of the bladder to adjacent fat. Scar formation and graft shrinkage in the control group were more serious than those in the experimental group. Bladder stone formation was found in the control group in one animal at 2 months, in two at 3 months, and in one at 6 months, while none presented in the experimental group. Three animals in the control group (one at 2 months, one at 3 months, and one at 6 months), and two animals in the experimental group (one at 2 months and one at 3 months) had central graft calcifications (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

The difference of macroscopic findings of tissue engineering neobladder at 6 months after operation between the control group (A, B) and the experimental group (C, D): obvious scar formation and graft shrinkage could be found through the observation of serosal surface in the control group (A). Meanwhile, stone formation could be found on the mucosal surface after opening the regenerated bladder (B). However, the regenerated zone was difficult to distinguish on the serosal surface in the experimental group (C). Scar formation and graft shrinkage were unconspicuous through the observation of mucosal surface. Furthermore, no stone formation can be found (D). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Urodynamic studies

The time course of functional status after bladder replacement with porcine BAM in the two groups was evaluated with urodynamic studies at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation (Fig. 2). Preoperative bladder capacity and compliance, which showed no significant difference between the experimental and control groups, represented the 100% values. At 1 month after surgery, the bladder capacity decreased to 59.8%±3.1% and 69.2%±3.7% of preoperative in the control and experimental group, respectively, showing no statistical significance (p>0.05). However, at 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery, bladder capacity recovery in the experimental group was better than that of the control (of preoperative; 74.8%±1.4%, 83.2%±1.4% and 95.3%±1.2% vs. 66.1%±2.5%, 68.5%±1.2% and 69.8%±2.5%, p<0.05). Bladder compliance of the experimental group was superior to that measured in the control group at 2, 3, and 6 months (of preoperative; 76.8%±5.5%, 78.8%±3.5%, and 92.3%±1.5% vs. 52.3%±1.0%, 62.2%±1.8%, and 59.4%±1.7%, p<0.05). Bladder volume and intravesical pressure curve showed that tissue-engineered neobladder in the experimental group performed a larger-capacity and lower-pressure reservoir for safe urine storage than in the control at 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery. After 6 months of surgery, bladder function of rabbits in the experimental group was already close to the function of normal bladder.

FIG. 2.

Bladder capacity (A) and bladder compliance (B) were evaluated at preoperation time and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery in both the control and experimental groups. Bladder capacity and compliance at preoperation time were considered as 100% (*p<0.05).

Organ bath studies

Under electrical field stimulation and carbachol interference, native bladder tissue exhibited good contraction, which showed a positive correlation with dose and stimulus frequency. Muscle strip in the marginal zone of the neobladder in the experimental rabbits exhibited similar contraction with that in native bladder and better contraction compared with that in the control rabbits after electrical field stimulation and carbachol interference. However, muscle strip in the central zone of the neobladder in the experimental rabbits exhibited some contraction inferior to that in the marginal zone, whereas no contraction was found in the central zone of the neobladder in the control rabbits (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Bladder tissue retrieved at 6 months after surgery in both the experimental and control groups was dissected to muscle strip for electrical field stimulation and carbachol interference. Retrieved bladder tissue was divided into the marginal zone and the central zone for examination, respectively. Normal bladder tissue was retrieved for examination as normal control.

Urothelium formation

HE stains showed regeneration of the urothelium. The urothelium was multilayered in the marginal zone and the central zone of tissue-engineered neobladder in both the control and the experimental groups at 1 month after operation (Fig. 4). At 6 months postoperation, the luminal surface of the tissue-engineered neobladder between the two groups was still showed multilayered tissue structure, which was similar with the native normal bladder.

FIG. 4.

Tissue-engineered neobladder urothelium formation was observed by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining (100×). Native rabbit bladder (A), central zone (B), and marginal zone (C) of neobladder in the experimental group and the central zone (D), and the marginal zone (E) of neobladder in the control group at 1 month after surgery (scale bars=100 μm). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Neovascularity

It was found that MVD and MVA gradually increased in the two groups over time. In the experimental group, MVD and MVA in the marginal zone of the neobladder tissues were all significantly higher than those in the control neobladder at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months postoperation (MVD: 24±1.6, 39±6.8, 50±6.8, and 58±2.9 vs. 16±2.5, 19±4.7, 23±1.8, and 25±2.5, p<0.05; MVA: % of total area: 3.38%±0.72%, 4.48%±0.88%, 4.68%±0.41%, and 6.03%±0.98% vs. 1.12%±0.23%, 2.1%±0.48%, 2.25%±0.47%, and 4.05%±0.53%, p<0.05; Fig. 5). However, no significant difference about MVD and MVA was found in the central zone of the neobladder in the two groups at any predetermined time point (p>0.05).

FIG. 5.

HE staining of marginal zone of the neobladder was performed to observe neovascularity (100×). The functional vessels could be evidenced in the neobladder (scale bars=100 μm). Neobladder at 1 [I(A)], 2 [I(B)], 3 [I(C)], and 6 [I(D)] months in the control group and at 1 [I(E)], 2 [I(F)], 3 [I(G)], and 6 [I(H)] months in the experimental group. Semiquantitative analysis indicated that both the microvessel area [II(A)] and microvessel density [II(B)] in the experimental rabbit neobladder were higher than those in the control group at each time points after surgery (*p<0.05). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Smooth muscle formation

To observe the proliferated cells and the regenerated smooth muscle bundle, retrieved bladder tissue of the neobladder was stained with PCNA and α-SMA. PCC and RPC in the marginal zone and the central zone of the neobladder tissues in the experimental group were all higher significantly than those in the control neobladder at 1 month postoperation (PCC: 247.2±11.3 vs. 200.6±13.6 in the marginal zone, p<0.05; 257.8±17.5 vs. 174.9±11.1 in the central zone, p<0.05; RPC: 87%±0.9% vs. 80%±1.8% in the marginal zone, p<0.05; 87%±1.8% vs. 71%±2.8% in the central zone, p<0.05). These significant differences in PCC and RPC were also found in the central zone of the neobladder tissues at 2 months postoperation (PCC: 240.2±17.6 vs. 191.2±14.6, p<0.05; RPC: 78%±2.2% vs. 68%±1.8%, p<0.05) and both the marginal and central zones at 3 months postoperation (PCC: 287.3±22.7 vs. 182.3±10.8 in the marginal zone, p<0.05; 224.9±13.0 vs. 170.5±16.2 in the central zone, p<0.05; RPC: 79%±1.7% vs. 73%±2.1% in the zone, p<0.05; 81%±2.0% vs. 69%±1.9% in the central zone, p<0.05). At 6 months postoperation, PCC and RPC in the marginal zone and the central zone of the neobladder tissue between two groups were similar and were also similar with those in the native bladder tissue (p>0.05) (Figs. 6 and 7).

FIG. 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of marginal zone of the neobladder with antibody against PCNA in control (A–D) and experimental (E–H) groups at 1 [I (A, E)], 2 [I (B, F)], 3 [I (C, G)], and 6 [I (D, H)] months after surgery. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (400×, scale bars=100 μm). Semiquantitative analysis indicated that both the proliferative cell count (PCC) [II(A)] and ratio of proliferative cells (RPC) [II(B)] in the experimental rabbit neobladder were higher than those in the control group at 1 and 3 months after surgery (*p<0.05). At 6 months postoperation, PCC and RPC in the two groups were similar and were also similar with those in the native bladder tissue. PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

FIG. 7.

Immunohistochemical staining of the central zone of the neobladder with antibody against PCNA in the control (A–D) and experimental (E–H) groups at 1 [I (A, E)], 2 [I (B, F)], 3 [I (C, G)], and 6 [I (D, H)] months after surgery. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (400×, scale bars=100 μm). Semiquantitative analysis indicated that both the PCC [II(A)] and RPC [II(B)] in the experimental rabbit neobladder were higher than those in the control group at 1, 2, and 3 months after surgery (*p<0.05). At 6 months postoperation, PCC and RPC in the two groups were similar and were also similar with those in the native bladder tissue. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

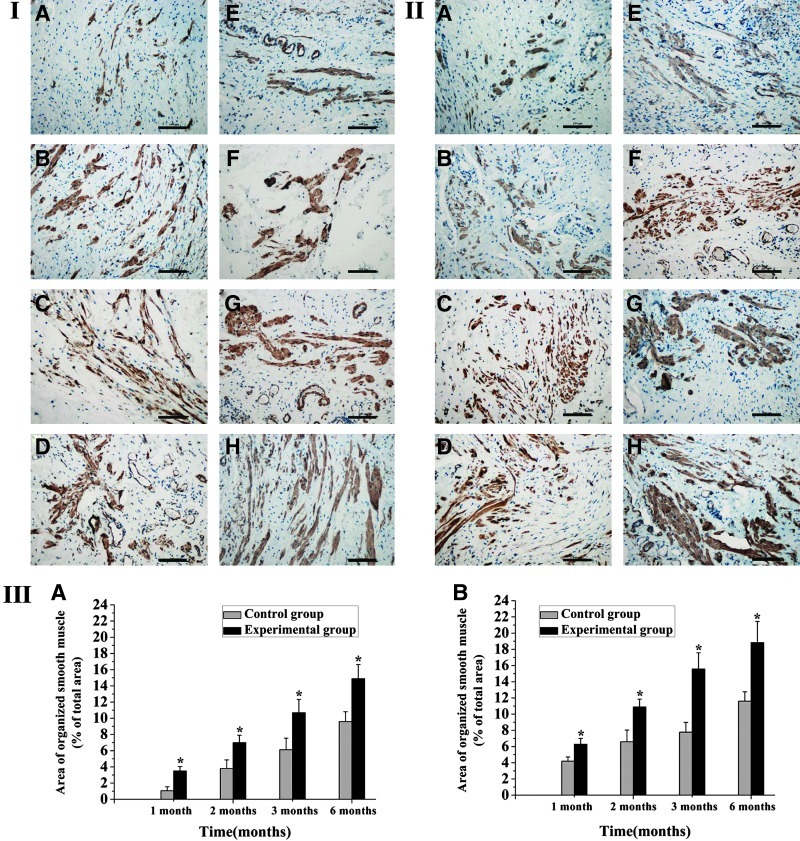

It was also found that smooth muscle buddle of the neobladder in the experimental group showed more regular arrangement compared with that in the control group at the 6-month group. The area of organized smooth muscle of the marginal and central zone in the experiment group was significantly larger than that in the control group at each time point (% of total area: 6.3%±0.7%, 10.9%±1.0%, 15.6%±2.0%, and 18.8%±2.6% vs. 4.2%±0.5%, 6.6%±1.4%, 7.8%±1.2%, and 11.6%±1.2% in the marginal zone, p<0.05; 3.5%±0.5%, 7.0%±0.9%, 10.7%±1.6%, and 14.9%±1.7% vs. 1.1%±0.5%, 3.8%±1.1%, 6.1%±1.4%, and 9.6%±1.2% in the central zone, p<0.05). Regenerated smooth muscle of the marginal and central zones in both groups increasingly improved with time. However, the experimental group still showed larger and more regular smooth muscle than the control group until 6 months postoperation (p<0.05) (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Immunohistochemical staining of central zone (I) and marginal zone (II) of the neobladder with antibody against SMA in control (A–D) and experimental (E–H) groups at 1 (A, E), 2 (B, F), 3 (C, G), and 6 (D, H) months after surgery (200×, scale bars=100 μm). Semiquantitative analysis indicated that the area of organized smooth muscle both of the central zone [III(A)] and the marginal zone [III(B)] in the experimental rabbit neobladder was higher than those in the control group at each time points after surgery (*p<0.05). SMA, smooth muscle actin. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

In addition, the central zone of the neobladder in the experimental group at 2 months was evaluated with immunofluorescent double staining. It was found that the PCNA-positive area was also SMA positive, which demonstrated that the proliferated cells were mainly smooth muscle cells (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Immunofluorescent double staining of central zone of the neobladder with an antibody against SMA and PCNA in the experimental group at 3 months after surgery (400×, scale bars=100 μm). (A) SMA + Alexa Fluor® 633, (B) PCNA + Alexa Fluor488, (C) DAPI, and (D) SMA + Alexa Fluor 633 + PCNA + Alexa Fluor 488 + DAPI. DAPI, 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Gelatinolytic assay findings

As indicated in Figure. 10I, three bands appeared at 84, 72, and 62 kDa, corresponding to activated MMP-9, pro-MMP-2, and activated MMP-2. The activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 of the native bladder tissue around tissue-engineered neobladder in the experimental group was higher than that in the control group at 1 and 2 months postoperation (p<0.05). Three and 6 months after operation, the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 declined, and no statistical difference was found between the two groups. However, the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the two groups was still higher than that in native bladder (Fig. 10II).

FIG. 10.

Gelatinolytic assay was performed to detect the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 of the native bladder tissue around tissue-engineered neobladder. (I) Electrophoresis strip of gelatinolytic assay. N: native bladder tissue of the rabbit preoperation, C: control rabbit, E: experimental rabbit. The strip of MMP-2 and MMP-9 could be found at 62 and 84 kDa. Semiquantitative analysis indicated that the activity of MMP-2 [II(A)] and MMP-9 [II(B)] in the experimental rabbit neobladder was higher than those in the control group at 1 and 2 months after surgery (*p<0.05). The activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was declined over time [II(A, B)]. The activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in native bladder tissue of the rabbit preoperation was considered as 100%. MMP-2, matrix metalloproteinase-2; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9.

Discussion

Tissue engineering of urinary bladder has brought a great hope to bladder repair and reconstruction. For bladder reconstruction, the crucial requirements are smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization.24 Urination is accomplished through bladder smooth muscle tissue contraction. Therefore, smooth muscle regeneration is essential for the recovery of contractile function of tissue-engineered neobladder. Vascularization is to establish a prompt and complete vascular network to supply nutrient and oxygen, which facilitate cell survival and bladder wall regeneration.10,24 We found that angiogenic growth factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), VEGF, and nerve growth factor (NGF), had been investigated in cell-free tissue-engineering approaches to facilitate bladder regeneration in a rat model.13,15,19 In these researches, angiogenesis and recovery of bladder function were improved by the exogenous bioactive factors. However, the reconstructed bladder was relatively small, and the regeneration speed was rapid in a rodent bladder model that did not present the bladder regeneration happened in large animal or human. The smooth muscle regeneration and angiogenesis are extremely crucial in tissue engineering of bladder, since many studies showed that smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization were unsatisfied when the reconstructed area was relative large.10,24 Therefore, we used a bioactive factor cocktail (two growth factors, PDGF-BB and VEGF) and investigated their role in bladder smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization in a relative large bladder tissue reconstruction model.

The natural extracellular matrix is thought as an ideal model for bioactive factor delivery system.17,25,26 In our previous study, we developed a porcine BAM with well-preserved extracellular sulfated GAG content,14 which has the ability of binding and protecting many bioactive factors in the native ECM.27,28 High levels of sulfated GAGs preserved in the porcine BAM can also serve as a reservoir for delivering exogenous bioactive factors. It is reported that exogenous bioactive factors being incorporated into the BAM would exhibit a sustained release pattern in accordance with biodegradation of BAM after implantation and promoted host parenchymal cell proliferation, migration, and tissue angiogenesis.15,17,25 In this study, lyophilized porcine BAM was rehydrated with PDGF-BB and VEGF-mixed solution and incubated for 12 h at 37°C, after which both the PDGF-BB and VEGF appeared incorporated well into the porcine BAM, which guaranteed localized and sustained delivery. As a result, we found that coadministration of these two bioactive factors indeed enhanced smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization of BAM. However, the growth factor slow-releasing and in vivo activity profile of PDGF-BB and VEGF from porcine BAM after bladder reconstruction needs to be further investigated. The optimal dosage of the bioactive factor cocktail needs to be well determined.

In evaluation of bladder regeneration, the surrogate areas have been detected as a whole during the histological analysis of smooth muscle regeneration and vessel formation,13,19,21 even in some large-area bladder reconstruction models.5,10 So far, the spatial distribution of bladder regeneration in the reconstructed area has not yet been investigated. In this study, we divided the bladder surrogate area into marginal zone and central zone to observe smooth muscle regeneration, vessel formation, and the recovery of contractive function of neobladder tissues, respectively. This method could be more reasonable in detecting the histological and functional recovery of tissue engineering urinary bladder and more conducive in analyzing the spatial distribution of bladder regeneration.

After a bladder was reconstructed with a tissue-engineering scaffold, urothelium of the host was activated and exhibited high proliferation potential.29 Therefore, urothelium formation could be well accomplished within a short time of 2–4 weeks.30–32 In our study, multilayered urothelium formed well in both the marginal zone and the central zone of the two groups at 1 month, which further supports the results of previous studies.

In view of vessel formation, more vessels were found in the experimental group than those in the control group after the analysis of the marginal area, while the analysis results of central area showed that there was no distinct difference. In the tissue organ bath studies, the results were different. Neobladder tissue in two areas exhibited different contraction after electrical field stimulation and carbachol interference. Contraction in the marginal zone of the control group was detected while strong contraction was detected in the experimental group, which was similar to the native bladder. In the central zone, weak contraction was detected in experimental group, while in control group, contraction was almost undetectable. Zhang et al. proposed that bladder regeneration appeared to depend on the revascularization rate of the scaffold.10 Low revascularization rate may contribute to unsatisfied bladder tissue contractile function.

Actually, when only the scaffold is implanted, bladder regeneration depends on the smooth muscle and vessels of surrounding normal bladder tissue ingrowths into the scaffold. However, this is an extremely slow process with a fairly limited effect.33,34 Several previous studies showed that replacement of the bladder with BAM combined with bFGF, NGF, and VEGF could stimulate growth and cell division, migration, and differentiation and facilitate the regeneration of smooth muscle and blood vessels of tissue-engineered neobladder.13,15,19 Chen et al. proposed that the addition of a collagen-binding domain to the N-terminal of native-bFGF could maintain growth factor activity and elevate the collagen-binding ability of bFGF, and then significantly promote angiogenesis at the target site, thus contributing to bladder regeneration.35 However, the effective mechanism of growth factors promoting smooth muscle regeneration and angiogenesis is still unclear.

The MMPs are very important enzymes that actively participate in tissue remodeling by degrading the basement membranes and extracellular matrix components, along with promoting cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. In normal adult tissue, they are almost undetectable, while their expression will be dramatically elevated during the process of wound healing by the stimulation of bioactive factors.36–38 It is reported that MMPs play a critical role on the regeneration of skeletal muscle, liver, cartilage, bone, and angiogenesis when the tissue-engineering approaches are utilized for tissue repair.36,37,39–44 In addition, some studies indicated that both smooth muscle cells and urothelial cells could secret MMP-2 and MMP-9 in vitro.45,46 In the present study, the native bladder tissues around the reconstruction area were retrieved to evaluate the MMPs. We found that the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the native bladder tissues in the experimental group was obviously higher than those in the control group. Therefore, we think that PDGF-BB and VEGF can promote bladder regeneration by elevating activity of MMPs. However, the exact mechanism of MMPs in the process of bladder regeneration needs to be further studied in the near future. Transgenic animal models that have overexpression and loss of MMPs might be a useful tool for such study. MMP antibodies and inhibitors can also be used to elucidate the exact roles that they play in bladder regeneration.38,43

In the present study, we found the difference of smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization between the marginal and central zones of tissue-engineered neobladder. Furthermore, smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization of tissue-engineered neobladder were still insufficient to obtain the recovery of contractive function of bladder tissues and maintain bladder function compared with native bladder. Bioactive factors might have a limited effect on promoting cell transference and proliferation when comes to large-area bladder replacement. Stem/progenitor cells as a kind of immature cells have a stronger proliferation ability than mature cells.47,48 They can secrete growth factors through a paracrine method to promote tissue regeneration.49 Future studies may consider the combined application of stem/progenitor cells to assist tissue engineering of urinary bladder.

Conclusion

This study indicated that the smooth muscle regeneration and vascularization in tissue-engineered neobladder and recovery of bladder function could be enhanced by BAM combined with PDGF-BB and VEGF. After bladder substitution with BAM incorporated with PDGF-BB and VEGF, upregulation of the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 of native bladder tissue around the tissue-engineered neobladder was detected. Subsequently, PDGF-BB might stimulate the adjacent bladder smooth muscle cell to migrate into the scaffold and proliferate in situ, and eventually form organized smooth muscle. Meanwhile, VEGF might stimulate the adjacent endothelial cell to migrate into the scaffold and proliferate in situ, and eventually form vasculature. Further researches should be conducted to increase smooth muscle buddle regeneration and vessel formation of the central zone of tissue engineering neobladder.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31100702/C100307).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Khoury J.M. Timmons S.L. Corbel L. Webster G.D. Complications of enterocystoplasty. Urology. 1992;40:9. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoury A.E. Salomon M. Doche R. Soboh F. Ackerley C. Jayanthi R. McLorie G.A. Mittelman M.W. Stone formation after augmentation cystoplasty: the role of intestinal mucus. J Urol. 1997;158:1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun S.Y. Lim G.J. Kwon T.G. Kwak E.K. Kim B.W. Atala A. Yoo J.J. Identification and characterization of bioactive factors in bladder submucosa matrix. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4251. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown A.L. Brook-Allred T.T. Waddell J.E. White J. Werkmeister J.A. Ramshaw J.A. Bagli D.J. Woodhouse K.A. Bladder acellular matrix as a substrate for studying in vitro bladder smooth muscle-urothelial cell interactions. Biomaterials. 2005;26:529. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merguerian P.A. Reddy P.P. Barrieras D.J. Wilson G.J. Woodhouse K. Bagli D.J. Mclorie G.A. Khoury A.E. Acellular bladder matrix allografts in the regeneration of functional bladders: evaluation of large-segment (>24 cm2) substitution in a porcine model. BJU Int. 2000;85:894. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Probst M. Piechota H.J. Dahiya R. Tanagho E.A. Homologous bladder augmentation in dog with the bladder acellular matrix graft. BJU Int. 2000;85:362. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crapo P.M. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3233. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert T.W. Sellaro T.L. Badylak S.F. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3675. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tayalia P. Mooney D.J. Controlled growth factor delivery for tissue engineering. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3269. doi: 10.1002/adma.200900241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y. Frimberger D. Cheng E.Y. Lin H.-K. Kropp B.P. Challenges in a larger bladder replacement with cell-seeded and unseeded small intestinal submucosa grafts in a subtotal cystectomy model. BJU Int. 2006;98:1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stehr M. Adam R.M. Khoury J. Zhuang L. Solomon K.R. Peters C.A. Freeman M.R. Platelet derived growth factor-BB is a potent mitogen for rat ureteral and human bladder smooth muscle cells: dependence on lipid rafts for cell signaling. J Urol. 2003;169:1165. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000041501.01323.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara N. Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:4. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youssif M. Shiina H. Urakami S. Gleason C. Nunes L. Igawa M. Enokida H. Tanagho E.A. Dahiya R. Effect of vascular endothelial growth factor on regeneration of bladder acellular matrix graft: histologic and functional evaluation. Urology. 2005;66:201. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang B. Zhang Y. Zhou L. Sun Z. Zheng J. Chen Y. Dai Y. Development of a porcine bladder acellular matrix with well-preserved extracellular bioactive factors for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:1201. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanematsu A. Yamamoto S. Noguchi T. Ozeki M. Tabata Y. Ogawa O. Bladder regeneration by bladder acellular matrix combined with sustained release of exogenous growth factor. J Urol. 2003;170:1633. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000084021.51099.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cartwright L. Farhat W.A. Sherman C. Chen J. Babyn P. Yeger H. Cheng H.L. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to quantify VEGF-enhanced tissue-engineered bladder graft neovascularization: pilot study. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77:390. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanematsu A. Yamamoto S. Ozeki M. Noguchi T. Kanatani I. Ogawa O. Tabata Y. Collagenous matrices as release carriers of exogenous growth factors. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4513. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanematsu A. Marui A. Yamamoto S. Ozeki M. Hirano Y. Yamamoto M. Ogawa O. Komeda M. Tabata Y. Type I collagen can function as a reservoir of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Control Release. 2004;99:281. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikuno N. Kawamoto K. Hirata H. Vejdani K. Kawakami K. Fandel T. Nunes L. Urakami S. Shiina H. Igawa M. Tanagho E. Dahiya R. Nerve growth factor combined with vascular endothelial growth factor enhances regeneration of bladder acellular matrix graft in spinal cord injury-induced neurogenic rat bladder. BJU Int. 2009;103:1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberpenning F. Meng J. Yoo J.J. Atala A. De novo reconstitution of a functional mammalian urinary bladder by tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:149. doi: 10.1038/6146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon T.G. Yoo J.J. Atala A. Local and systemic effects of a tissue engineered neobladder in a canine cystoplasty model. J Urol. 2008;179:2035. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piechota H.J. Dahms S.E. Nunes L.S. Dahiya R. Lue T.F. Tanagho E.A. In vitro functional properties of the rat bladder regenerated by the bladder acellular matrix graft. J Urol. 1998;159:1717. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka S.T. Thangappan R. Eandi J.A. Leung K.N. Kurzrock E.A. Bladder wall transplantation—long-term survival of cells: implications for bioengineering and clinical application. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2121. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanematsu A. Yamamoto S. Ogawa O. Changing concepts of bladder regeneration. Int J Urol. 2007;14:673. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babensee J.E. McIntire L.V. Mikos A.G. Growth factor delivery for tissue engineering. Pharm Res. 2000;17:497. doi: 10.1023/a:1007502828372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wissink M.J. Beernink R. Pieper J.S. Poot A.A. Engbers G.H. Beugeling T. van Aken W.G. Feijen J. Binding and release of basic fibroblast growth factor from heparinized collagen matrices. Biomaterials. 2001;22:2291. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schonherr E. Hausser H.J. Extracellular matrix and cytokines: a functional unit. Dev Immunol. 2000;7:89. doi: 10.1155/2000/31748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zafiropoulos A. Fthenou E. Chatzinikolaou G. Tzanakakis G.N. Glycosaminoglycans and PDGF signaling in mesenchymal cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49:153. doi: 10.1080/03008200802148702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staack A. Hayward S.W. Baskin L.S. Cunha G.R. Molecular, cellular and developmental biology of urothelium as a basis of bladder regeneration. Differentiation. 2005;73:121. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy P.P. Barrieras D.J. Wilson G. Bagli D.J. McLorie G.A. Khoury A.E. Merguerian P.A. Regeneration of functional bladder substitutes using large segment acellular matrix allografts in a porcine model. J Urol. 2000;164:936. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuininga J.E. Moerkerk H.V. Hanssen A. Hulsbergen C.A. Oosterwijk-Wakka J. Oosterwijk E. de Gier R.P. Schalken J.A. van Kuppevelt T.H. Feitz W.F.J. A rabbit model to tissue engineer the bladder. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1657. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obara T. Matsuura S. Narita S. Satoh S. Tsuchiya N. Habuchi T. Bladder acellular matrix grafting regenerates urinary bladder in the spinal cord injury rat. Urology. 2006;68:892. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laschke M.W. Harder Y. Amon M. Martin I. Farhadi J. Ring A. Torio-Padron N. Schramm R. Rucker M. Junker D. Haufel J.M. Carvalho C. Heberer M. Germann G. Vollmar B. Menger M.D. Angiogenesis in tissue engineering: breathing life into constructed tissue substitutes. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2093. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain R.K. Au P. Tam J. Duda D.G. Fukumura D. Engineering vascularized tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:821. doi: 10.1038/nbt0705-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen W. Shi C. Yi S. Chen B. Zhang W. Fang Z. Wei Z. Jiang S. Sun X. Hou X. Xiao Z. Ye G. Dai J. Bladder regeneration by collagen scaffolds with collagen binding human basic fibroblast growth factor. J Urol. 2010;183:2432. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellayr I.H. Mu X. Li Y. Biochemical insights into the role of matrix metalloproteinases in regeneration: challenges and recent developments. Future Med Chem. 2009;1:1095. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heissig B. Nishida C. Tashiro Y. Sato Y. Ishihara M. Ohki M. Gritli I. Rosenkvist J. Hattori K. Role of neutrophil-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 in tissue regeneration. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:765. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vu T.H. Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: effectors of development and normal physiology. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2123. doi: 10.1101/gad.815400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pauly R.R. Passaniti A. Bilato C. Monticone R. Cheng L. Papadopoulos N. Gluzband Y.A. Smith L. Weinstein C. Lakatta E.G., et al. Migration of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells through a basement membrane barrier requires type IV collagenase activity and is inhibited by cellular differentiation. Circ Res. 1994;75:41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim T.H. Mars W.M. Stolz D.B. Michalopoulos G.K. Expression and activation of pro-MMP-2 and pro-MMP-9 during rat liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2000;31:75. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lutolf M.P. Lauer-Fields J.L. Schmoekel H.G. Metters A.T. Weber F.E. Fields G.B. Hubbell J.A. Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive hydrogels for the conduction of tissue regeneration: engineering cell-invasion characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H. Feng F. Bingham C.O., 3rd Elisseeff J.H. Matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitors in cartilage tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6:144. doi: 10.1002/term.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimowska M. Olszynski K.H. Swierczynska M. Streminska W. Ciemerych M.A. Decrease of MMP-9 activity improves soleus muscle regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1183. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glaeser J.D. Geissler S. Ode A. Schipp C.J. Matziolis G. Taylor W.R. Knaus P. Perka C. Duda G.N. Kasper G. Modulation of matrix metalloprotease-2 levels by mechanical loading of three-dimensional mesenchymal stem cell constructs: impact on in vitro tube formation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:3139. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson C. Galis Z.S. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 differentially regulate smooth muscle cell migration and cell-mediated collagen organization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:54. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000100402.69997.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Booth C. Harnden P. Selby P.J. Trejdosiewicz L.K. Southgate J. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in an in vitro model of bladder tumor invasion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;462:413. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4737-2_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang B. Peng B. Zheng J. Cell-based tissue-engineered urethras. Lancet. 2011;378:568. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bompais H. Chagraoui J. Canron X. Crisan M. Liu X.H. Anjo A. Tolla-Le Port C. Leboeuf M. Charbord P. Bikfalvi A. Uzan G. Human endothelial cells derived from circulating progenitors display specific functional properties compared with mature vessel wall endothelial cells. Blood. 2004;103:2577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foubert P. Matrone G. Souttou B. Lere-Dean C. Barateau V. Plouet J. Le Ricousse-Roussanne S. Levy B.I. Silvestre J.S. Tobelem G. Coadministration of endothelial and smooth muscle progenitor cells enhances the efficiency of proangiogenic cell-based therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]