Abstract

In this study, we describe the development of oligopeptide-modified cell culture surfaces from which adherent cells can be rapidly detached by application of an electrical stimulus. An oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEK, was designed with a terminal cysteine residue to mediate binding to a gold surface via a gold–thiolate bond. The peptide forms a self-assembled monolayer through the electrostatic force between the sequence of alternating charged glutamic acid (E) and lysine (K) residues. The dense and electrically neutral oligopeptide zwitterionic layer of the modified surface was resistant to nonspecific adsorption of proteins and adhesion of cells, while the surface was altered to cell adhesive by the addition of a second oligopeptide (CGGGKEKEKEKGRGDSP) containing the RGD cell adhesion motif. Application of a negative electrical potential to this gold surface cleaved the gold–thiolate bond, leading to desorption of the oligopeptide layer, and rapid (within 2 min) detachment of virtually all cells. This approach was applicable not only to detachment of cell sheets but also for transfer of cell micropatterns to a hydrogel. This electrochemical approach of cell detachment may be a useful tool for tissue-engineering applications.

Introduction

The spatial and temporal control of the biointerface between adherent cells and materials remains an important challenge in biomaterial science.1 The ability to dynamically control the cell adhesive properties of a substrate has recently been shown to be a powerful tool that may foster advances in diverse fields, ranging from cell biology to tissue engineering.2 Early and excellent examples of manipulation of attachment and detachment of cell layers were reported using a thermally responsive polymer, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide).3 Several types of cell sheets, including those composed of myocardial and hepatic cells, were noninvasively detached from thermally responsive surfaces and stacked to form multilayered cell sheets.4,5 Clinical results using this thermoresponsive technology have shown that reconstructed corneal tissues remain clear and mediate improved visual acuity over 1-year follow-up after transplantation of corneal epithelial cell sheets.6 However, one potential drawback to this approach could be that the harvesting of cells typically requires 40–60 min at a low temperature.7,8 Promising alternative approaches have been reported using electrochemically responsive surfaces. For instance, quinone ester and O-silyl hydroquinone electroactive groups have been used to selectively release cell adhesive ligands, and thus the adherent cells, in response to application of reductive or oxidative potentials.9 Similarly, application of an electrical stimulus to electrodes coated with hydrogels and polyelectrolyte layers has also been used to detach adherent cells.10,11 One promising feature of such electrochemical approaches is that cells can be detached not only from a flat surface but also from substrates of varying configuration, such as microarrayed electrodes for spatially controlled single-cell detachment12 and cylindrical rods for fabricating three-dimensional vascular-like structures.13,14

To date, our group has used two different molecular supports for electrochemically detaching cells from a surface. In the first approach, an alkanethiol self-assembled monolayer (SAM) was formed on a gold electrode, and the alkanethiol carboxyterminals were coupled to RGD peptides to mediate cell adhesion.15 The second approach employed a custom-designed bridge-shaped oligopeptide, CCRRGDWLC, which spontaneously adsorbed onto the gold surface via the terminal cysteines and mediated cell adhesion through the central RGD sequence.13,16 In both approaches, the molecules adsorbed to the gold surface via formation of a gold–thiolate bond. This bond can be reductively cleaved by applying a negative electrical potential, thereby detaching adherent cells along with desorption of the molecules. Our results demonstrated that cells and cell sheets could be rapidly harvested from the gold surface using both these approaches. Indeed, the alkanethiol SAM-based approach allowed almost 100% cell retrieval after application of a negative potential for only 5 min. In this case, however, the detached cells may retain the alkanethiol molecules. In previous studies, alkanethiol SAM-coated surfaces have been shown to cause local acute inflammatory reactions and adhesion of leukocytes in vivo.17,18 It is possible that alkanethiol molecules transferred with the cells induce the inflammatory reaction, which would compromise the biocompatibility of this approach. Furthermore, chemical agents used to couple RGD peptides to the carboxyterminals of alkanethiol SAMs could also be a source of toxic contaminants. The use of oligopeptides represents a promising alternative to overcome the problem of biocompatibility for the use in humans; peptides are naturally occurring molecules, and there are many enzymatic routes for their degradation in vivo. In addition, the chemistry to generate peptide–SAMs does not require additional potentially toxic substances. However, in our previous studies, using the bridge-shaped oligopeptide, we found that ∼10% of cells remained attached on the surface even after 7 min of potential application. The efficient cell detachment using the alkanethiol SAM is likely due to this molecule's ability to form a dense molecular layer on the gold surface, preventing nonspecific protein adsorption. In contrast, the amino acid sequence of the bridge-shaped oligopeptide was not optimized for generation of compact layers, and most likely allowed some nonspecific protein adsorption that impaired cell detachment. In the present study, we hypothesized that such limitations in cell detachment could be overcome by designing an oligopeptide SAM that forms a dense layer on the gold surface. Thus, we aimed to design novel oligopeptides that would allow rapid and reliable electrochemical desorption for cell retrieval, whereas avoiding the biocompatibility concerns inherent to the alkanethiol-based approaches.

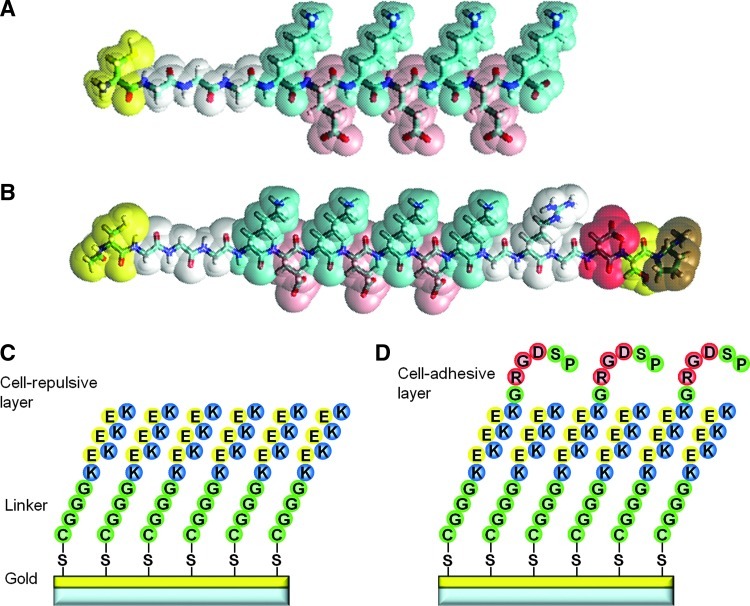

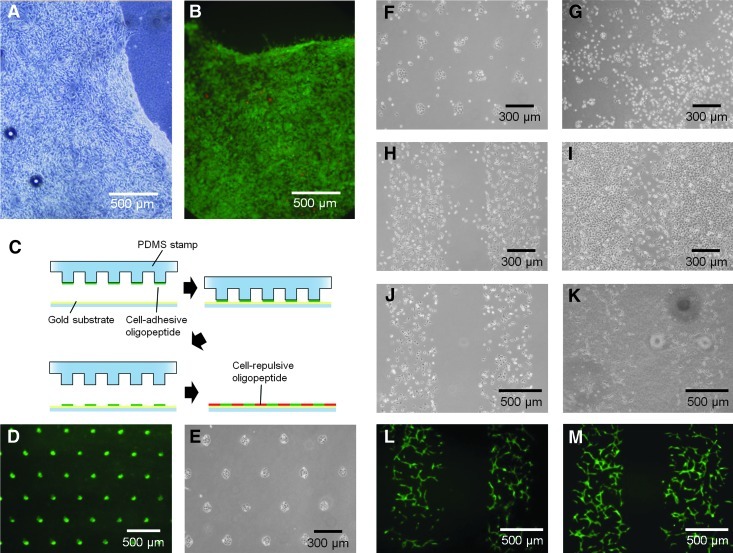

To fulfill this aim, we prepared two zwitterionic oligopeptides that promote dense monolayer formation by exploiting intermolecular electrostatic forces (Fig. 1). We characterized the modified surface in terms of molecular density and inhibition of nonspecific protein adsorption, and additionally evaluated the ability of the oligopeptides to support efficient and rapid cell detachment upon electrical potential application. Finally, we explored the potential for this approach to be exploited as a tool for manipulating cell sheets and cell micropatterns for tissue engineering in vitro.

FIG. 1.

Design of zwitterionic oligopeptides. (A) Cell-repulsive oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEK. (B) Cell-adhesive oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEKGRGDSP. Yellow, cysteine; white, glycine; blue, lysine; and red, glutamic acid. Both oligopeptides contain a terminal cysteine C that mediates binding to the gold surface through a gold–thiolate bond. Oligopeptides also contain a linker of three glycines G and an alternating positively charged lysine K and negatively charged glutamic acid E residues. K and E support formation of a dense self-assembled monolayer (SAM) through electrostatic forces. (C) SAM of the cell-repulsive oligopeptide. (D) SAM of the mixture of cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive oligopeptide. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

Swiss 3T3 murine fibroblasts (RCB1642) were purchased from the Riken Cell Bank, Japan. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP-HUVEC) were a generous gift from Dr. J. Folkman (Children's Hospital Boston). Endothelial basal medium-2 (EBM-2, CC-3156) and SingleQuots growth supplement (CC-3162) were purchased from Cambrex Bio Science. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs) were purchased from Lonza. Cell culture reagents were purchased from the following commercial sources: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) from Invitrogen; type I collagen solution from Nitta Gelatin; fibronectin and fibrinogen from Sigma; fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and ethidium bromide (EB) from Wako Pure Chemicals Industries.

The materials for the fabrication of culture substrates were as follows: microcover glass (24×24 mm) from Matsunami; a thick-film photoresist (SU-8) from MicroChem; poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) from ShinEtsu Chemical; cell-repulsive oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEK (Fig. 1A), cell-adhesive oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEKGRGDSP (Fig. 1B), and bridge-shaped oligopeptide, CCRRGDWLC,13 from Sigma-Aldrich.

Gold surface modification with oligopeptides and assessment of nonfouling properties

A quartz crystal microbalance (QCM, AFFINIX QN; Initium) was used to quantify adsorption of the cell-repulsive oligopeptide (Fig. 1C) or the bridge-shaped oligopeptide on the gold surface, and to estimate the nonfouling properties of the oligopeptide-modified surfaces after protein adsorption. QCM gold electrodes were cleaned with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and a piranha solution (H2SO4:H2O2, 3:1), then rinsed with double distilled water (ddH2O; Milli-Q Advantage; Millipore), and dried under N2. The electrodes were immersed in a 50-μM solution of cell-repulsive or bridge-shaped oligopeptides for 1 h at room temperature, and then rinsed with ddH2O and dried. The adsorbed oligopeptide was quantified by the change in the resonance frequency calculated using the Sauerbrey equation. The modified electrodes were then immersed in a 1.0 mg/mL aqueous solution of fibronectin or fibrinogen for 30 min at room temperature. After washing with ddH2O and drying with N2, the adsorbed protein was again quantified by the change in the resonance frequency. An unmodified gold electrode was used as a reference surface.

Cell adhesion on oligopeptide-modified gold surfaces

Gold surfaces were prepared by sputter coating a chromium layer and an ∼40-nm gold layer on microcover glasses using a sputtering machine (CFS-4ES; Shibaura). The gold-coated substrates were modified by overnight immersion at 4°C in a series of 50-μM solutions containing varying amounts of the two oligopeptides (Fig. 1D). The molar ratio of cell-adhesive to cell-repulsive oligopeptides (Fig. 1A, B) in the solutions was 100:0, 99:1, 99.9:0.1, 99.99:0.01, 99.999:0.001, and 0:100 (total concentration: 50 μM). To prepare these solutions, 0.2 mL of a 50-μM solution of the cell-adhesive oligopeptide was mixed with 1.8 mL of a 50-μM solution of the cell-repulsive oligopeptide. Subsequently, 0.2 mL of this solution was mixed with 1.8 mL of a 100% cell-repulsive oligopeptide solution to obtain a solution of 99:1 cell-repulsive to cell-adhesive oligopeptide. This procedure was repeated sequentially to generate solutions with ratios of 99.9:0.1, 99.99:0.01, and 99.999:0.001 cell-repulsive to cell-adhesive oligopeptide. The modified substrates were then rinsed with ddH2O, followed by 70% ethanol, and were placed in wells of a six-well plate. Fibroblasts were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/mL in 2 mL/well in the DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Plates were incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 3 h at 37°C, after which nonadherent cells were removed by gently rinsing with PBS.15 Phase-contrast images were acquired, and the number of adherent cells was quantified using image analysis software (Nano Hunter NS2K-Pro; Nanosystem Corp.). Growth of cells on the oligopeptide-modified substrates was also examined over 4 days in culture. To do this, fibroblasts were seeded on the modified substrates at a lower cell density (5×104 cells/mL in 2 mL/well), and phase-contrast images were taken to quantify the adherent cells after culture for 3 h, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 4 days.

Electrochemical detachment of cells

We employed cyclic voltammetry to determine the potential required for reductive desorption of the oligopeptides from the modified gold surfaces. For this experiment, an electrolyte solution containing 0.5 M KOH was deoxygenated by bubbling with N2 gas for 20 min immediately before the measurement. The deoxygenation step is required to eliminate the interfering current generated by reduction of oxygen. The gold substrate was modified by immersion in a 50-μM solution of cell-adhesive oligopeptide overnight at 4°C. The oligopeptide-modified gold electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (#2080 A; Horiba), and a platinum auxiliary electrode were then placed in the electrolyte solution and connected to an electrochemical measurement system (AUTOLAB; Metrohm Autolab). A cyclic voltammogram was recorded at a scanning rate of 20 mV/s from 0 to −1.0 V. In this study, all potential values refer to those measured with respect to the Ag/AgCl electrode.

To examine cell detachment, fibroblasts were seeded on the modified substrates (2.5×105 cells/mL, 2 mL/well) and cultured as described above. After 1 day of culture, the substrates were rinsed three times with PBS and immersed in PBS with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a platinum auxiliary electrode. The substrate and electrodes were then connected to a potentiostat (HA-151; Hokuto Denko), and −1.0 V was applied for 1, 2, or 3 min. The substrates were then removed, gently rinsed, and phase-contrast micrographs were taken to quantify the adherent cells. Control substrates included unmodified gold surfaces or surfaces modified with the bridge-shaped oligopeptide or 10-carboxy-1-decanethiol.

Electrochemical detachment of cell sheets

We also examined whether this detachment method could be used for cell sheets in addition to single cells. For these experiments, hBMSCs were suspended at 5×105 cells/mL in the DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and 2 mL was seeded onto the modified or control substrates and placed in a 35-mm dish. Cells were cultured for 3 days until they reached confluence on the substrate. A collagen solution (2.4 mg/mL in 10×Ham's F12 medium, 0.05 N NaOH, 200 mM HEPES, and 2.2% [wt/v] NaHCO3) was freshly prepared, and a few drops were poured onto the confluent cell sheet and then allowed to gel. A potential of −1.0 V was applied for 5 min, and the gel layer was peeled from the substrate surface. The viability of detached cells was evaluated using a live/dead fluorometric assay using FDA and EB.19 Viable cells were identified by the green cytoplasmic fluorescence of FDA, whereas the dead cells showed red nuclear fluorescence due to binding of EB.

Micropatterning of the oligopeptides and cells

The cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive oligopeptides were patterned on the gold substrates by using microcontact printing.20 Briefly, masters for preparing the PDMS mold were fabricated with SU-8 photoresist. The prepolymer solution composed of a silicone elastomer and a curing agent (10:1) was poured onto the molds and cured at 80°C for 30 min. The cured PDMS stamps were then peeled from the mold and cleaned with ethanol. To form the alternating patterns of cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive surfaces, the PDMS stamps were inked with a 50-μM solution of cell-adhesive oligopeptide and pressed gently onto the gold substrates for 5 min at room temperature. The stamps were peeled off, and the substrates were rinsed with ddH2O and then immersed in a 50-μM solution of cell-repulsive oligopeptide overnight at 4°C. The substrates were removed from the solution and rinsed with ddH2O, followed by 70% ethanol. Each substrate was then placed in a well of a six-well plate; fibroblasts were added (2.5×105 cells/mL, 2 mL/well), and the plates were incubated at 37°C. After 3 h of culture, the medium was replaced with a fresh medium. To quantify cell adhesion to the modified surfaces, cells were cultured for 3 h, 1 days, or 2 days; the modified substrates were removed and rinsed, and phase-contrast images were acquired as described above.

Transfer of cell micropatterns from gold substrates to collagen gels

The cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive oligopeptides were spatially patterned on gold substrates by microcontact printing as mentioned earlier. Modified substrates were cultured with GFP-HUVECs (2.5×105 cells/mL in 2 mL/well) in EBM-2 supplemented with SingleQuots growth supplement. After 3 h of culture, the culture medium was aspirated, and a type I collagen solution (2.4 mg/mL) was poured on the gold substrates and allowed to gel. A potential of −1.0 V was applied for 5 min, and the gel layer was then peeled from the substrate and placed into culture. Cells expressing GFP were observed at 3 h, 1 day, 2 days, and 3 days of culture on the collagen gels.

Data analysis

Data are expressed as means±SD and were calculated from the results of at least three independent experiments. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated by the Dunnett's test for Figures 2 and 3B, by single-factor ANOVA for Figure 3C, and by Student's t-test for Figure 4D. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

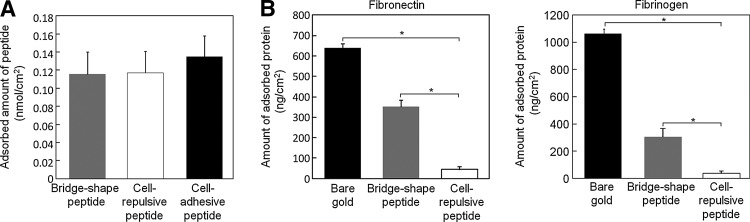

FIG. 2.

Oligopeptide-modified gold surfaces and their nonfouling properties. (A) Spontaneous adsorption of cell-repulsive, cell-adhesive, and bridge-shaped oligopeptides. (B) Fibronectin and fibrinogen adsorption onto bare gold surfaces, or gold surfaces modified with the bridge-shaped or cell-repulsive oligopeptides. The error bars indicate SD calculated from three independent quartz crystal microbalance measurements. *p<0.05 compared to the bare gold and bridge-shaped oligopeptide surfaces.

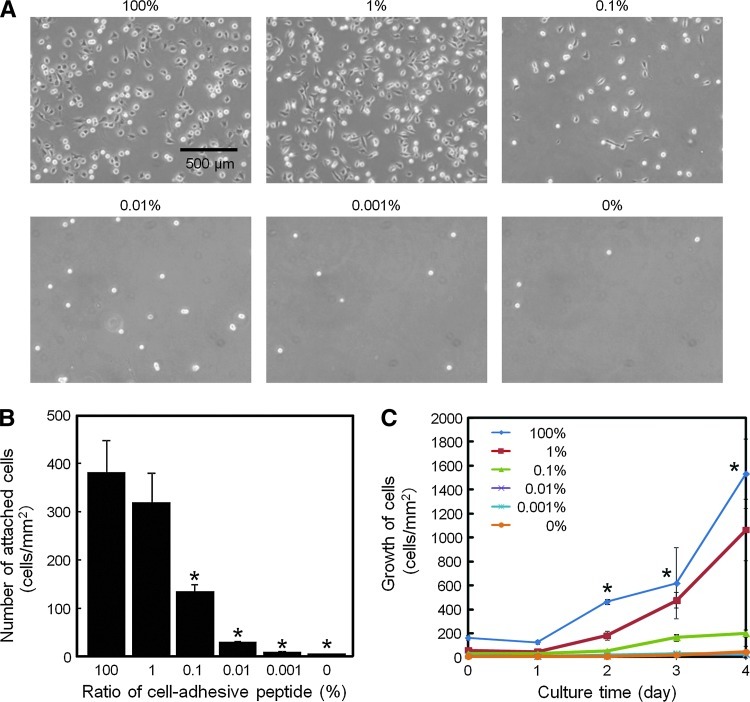

FIG. 3.

Cell adhesion and growth on substrates prepared with different ratios of zwitterionic oligopeptides. (A) Phase-contrast images of cells after 3 h of culture. The percentage value above each panel indicates the molar ratio of the cell-adhesive oligopeptide to the cell-repulsive oligopeptide. (B) Quantitation of adherent cells obtained from image analyses. (C) Growth of adherent cells. The error bars indicate SD calculated from three independent experiments for each substrate. *p<0.05 compared to the 100% cell-adhesive oligopeptide (B), or equal to or less than 0.1% cell-adhesive oligopeptide (C). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

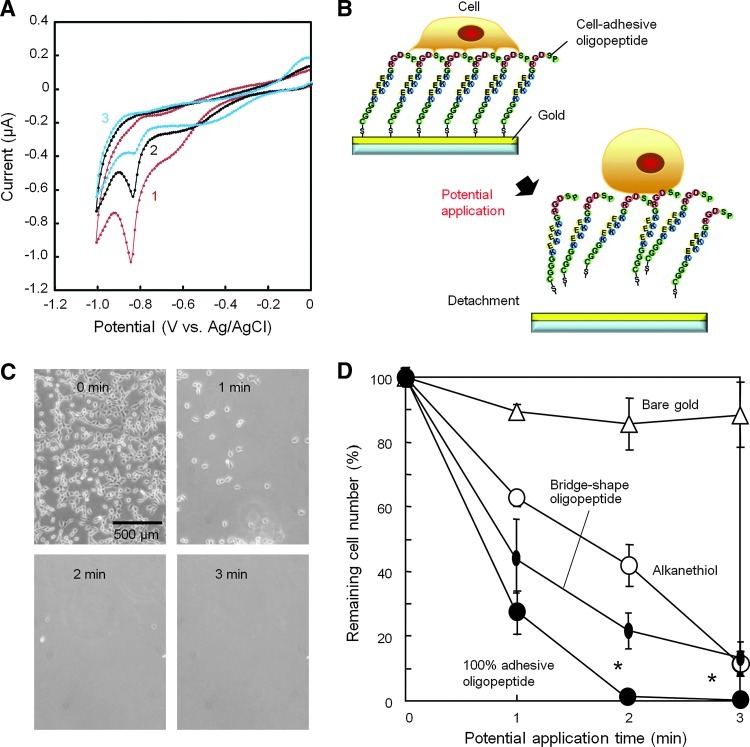

FIG. 4.

Cell detachment after electrochemical desorption of the zwitterionic oligopeptides. (A) Cyclic voltammogram obtained during the reductive desorption of the oligopeptide; 1, 2, and 3 are scan numbers. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded at a scanning rate of 20 mV/s with respect to an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The working electrode area was 8.0 mm2. (B) Schematic diagram of the electrochemical detachment of cells along with desorption of the oligopeptide. (C) Phase-contrast micrographs indicating fibroblasts on the gold surface modified with the cell-adhesive oligopeptide were readily detached within 2 min. (D) Percentage fibroblasts remaining bound to substrate after negative potential application. Cells were enumerated by image analysis of surfaces modified with the cell-adhesive oligopeptide, bridge-shaped oligopeptide, 10-carboxy-1-decanethiol, or bare gold surface. Potential application was −1.0 V with respect to an Ag/AgCl reference. The error bars indicate SD calculated from three independent experiments for each plot. *p<0.05 compared to the bridge-shaped oligopeptide. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Results and Discussion

Adsorption of proteins on oligopeptide-modified gold surfaces

The oligopeptides used in the present study were designed with alternating positively charged lysine (K) and negatively charged glutamic acid (E) residues (Fig. 1A, B), which contributed to the formation of a dense SAM through electrostatic forces.21 The QCM measurements revealed that all three oligopeptides spontaneously adsorbed onto the gold surface. The adsorbed amounts of the cell-repulsive oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEK, and the cell-adhesive oligopeptide, CGGGKEKEKEKGRGDSP, were 140±28 ng/cm2 and 237±49 ng/cm2, respectively. There is little difference in the adsorbed molecular density between the oligopeptides when their molecular weights are taken into account (Fig. 2A). When the oligopeptides are aligned in the tetragonal configuration, these values are equivalent to an intermolecular distance of ∼1.2 nm. This indicates the formation of a dense molecular layer, given that the intermolecular distance for alkanethiol SAMs is ∼0.5 nm,22 and an α-helix is ∼1.2 nm in diameter.23

We next investigated whether nonspecific adsorption of proteins was blocked by the oligopeptide modification of the gold substrate. Two major glycoprotein components in the body, fibronectin and fibrinogen, were used for the experiments. Fibronectin, one of the extracellular matrix components, mediates cell adhesion through interactions with cell surface integrin receptors, and also serves as a bridge connecting other extracellular matrix components. Fibrinogen is a soluble plasma glycoprotein that is structurally similar to fibronectin and readily adsorbs onto culture surfaces to mediate cell adhesion.24 Because both fibronectin and fibrinogen show avid nonspecific binding to various materials, a surface that can repel binding of these proteins may be useful for applications requiring controlled cell adhesion for cell micropatterning and electrochemical detachment. As shown in Figure 2B, the adsorption of both fibronectin and fibrinogen onto the gold surface was reduced by surface modification with the bridge-shaped and cell-repulsive oligopeptides; however, the zwitterionic oligopeptide modification was particularly effective in this regard. Thus, our results highlight the enhanced nonfouling properties of the oligopeptide modification when a zwitterionic molecule was used. This is consistent with previous reports in which peptides containing uniformly distributed negatively and positively charged residues were developed for ultra-low-fouling surface modifications.21

Contrary to our expectations, there was no difference in the amount of cell-repulsive and bridge-shaped oligopeptides adsorbed to the gold substrates (Fig. 2A). Nonetheless, there was a clear difference in the nonfouling properties of the two oligopeptides (Fig. 2B), which is likely due to the difference in the shapes adopted by the adsorbed molecules. The terminal cysteines of the bridge-shaped oligopeptides could form disulfide bonds with other molecules to create long molecular chains. This is far less likely to occur with the zwitterionic oligopeptide, because it contains only one cysteine, which favors formation of a densely packed single molecular layer.

Cell adhesion on oligopeptide-modified gold surfaces

To investigate the effects of the cell-repulsive and cell-adhesive oligopeptides on cell adhesion, the gold surfaces were modified with solutions containing varying molar ratios of the two zwitterionic molecules, ranging from 100% cell-adhesive oligopeptide to 100% cell-repulsive oligopeptide (Fig. 1D). After fibroblasts had been cultured on these surfaces for 3 h at 37°C, the substrates were washed, and images of the adherent cells were acquired. As expected, the number of adherent fibroblasts decreased in proportion to the decreasing ratio of the cell-adhesive to the cell-repulsive oligopeptide (Fig. 3A). Adherent cells exhibited a spread and extended morphology when incubated on surfaces coated with 100% and 1% cell-adhesive oligopeptide, but this was reduced on 0.1% surfaces, and almost all cells had a rounded morphology when present on surfaces modified with 0.01%, 0.0001%, and 0% cell-adhesive oligopeptide. Quantification of the images acquired after the 3-h incubation showed a small and insignificant difference (p=0.10) in the number of adherent cells on surfaces modified with 100% and 1% cell-adhesive oligopeptide (Fig. 3B). However, a further decrease in the oligopeptide ratio resulted in a dramatic reduction in the number of adherent cells. The modified surfaces also differed in their ability to support the growth of fibroblasts over 4 days of culture (Fig. 3C). Cells proliferated well on the surfaces with 100% and 1% cell-adhesive oligopeptide, with slightly better proliferation observed with 100% cell-adhesive oligopeptide. In contrast, cell proliferation was strongly limited on surfaces coated with <0.1% cell-adhesive oligopeptide. On day 2 of culture, the relative growth rate, calculated as the ratio of cells present compared to the initial cell number, was 2.9 and 3.0 for 100% and 1% surfaces, respectively, but was 1.7, 0.8, 1.5, and 0.9 for surfaces coated with 0.1%, 0.01%, 0.001%, and 0% cell-adhesive oligopeptide, respectively.

The minimum RGD density necessary to support cell adhesion has previously been examined for gold surfaces using mixed alkanethiol SAMs presenting RGD peptides and oligoethylene glycol. In those studies, the minimum RGD densities for cell adhesion and cell spreading were shown to be 0.001% and 0.1%, respectively, expressed as the ratio of RGD alkanethiol to oligoethylene glycol alkanethiol.25,26 The RGD molar density was calculated based on the assumption that the relative molar ratio of the alkanethiols is the same in solution and on the gold surface; although this assumption may not be completely accurate, the relative trends are likely to be similar.27,28 We also assumed that the RGD alkanethiols and oligoethylene glycol alkanethiols formed well-packed SAMs28 with a molecular density of 0.93 nmol/cm2.22 Based on those assumptions, the minimum RGD density necessary to support cell adhesion and cell spreading was calculated to be 9.3 and 930 fmol/cm2, respectively. In the present study, we estimated the density of surface-adsorbed zwitterionic oligopeptide to be 140 ng/cm2, and noted that the transition between supportive and nonsupportive substrates was observed in surfaces coated with 0.1% ratio of cell-adhesive to cell-repulsive oligopeptides. Therefore, if we again assume that the ratio of oligopeptides in solution is proportional to that on the gold surface, then we calculate the RGD density required to support fibroblast adhesion at 140 fmol/cm2. This calculation is an estimate and does not consider three-dimensional architecture and dynamics. Nevertheless, this estimate does suggest that the results observed here with oligopeptides are consistent with the previous reports using alkanethiol SAMs.

Detachment of cells after electrochemical desorption of oligopeptides

It is well documented that molecules adsorbed onto gold surfaces via gold–thiolate bonds can be reductively desorbed by applying a negative electrical potential.22 In our previous studies, cells adhering on gold surfaces modified with either alkanethiol SAM or the bridge-shaped oligopeptides were detached by applying −1.0 V with respect to an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.13,15 Here, we characterized the zwitterionic oligopeptide desorption process by cyclic voltammetry analysis, which showed that the peak potential for the reductive desorption of the oligopeptide appeared at −0.85 V in the first scan (Fig. 4A). In the second and third scans, the apparent peak at −0.85 V decreased, demonstrating that the oligopeptide was readily desorbed by the potential scanning. These measurements were performed in a strong alkaline KOH solution, whereas the cell detachment experiments were performed in PBS. The difference between the solutions could result in a potential shift of <100 mV.29 In addition, the electrical resistance of the cells themselves may cause a drop in the potential. Considering the unpredictability of such contributions, we used a potential of −1.0 V for the detachment of cells in the subsequent experiments.

To examine detachment of cells adhering on a gold surface via the cell-adhesive oligopeptide (Fig. 4B), we acquired phase-contrast images after application of −1.0 V for 1, 2, or 3 min (Fig. 4C), and quantified the adherent cells. Although relatively few cells detached from the bare gold surface over the 3-min period, almost all cells detached within 2 min from the surfaces modified with the cell-adhesive zwitterionic oligopeptide (Fig. 4D). Detachment from the zwitterionic peptide-modified surface was much more rapid than from either the alkanethiol or bridge-shaped oligopeptide-modified surfaces. Notably, 100% of cells detached with the zwitterionic oligopeptide, whereas ∼10% of cells did not detach with the bridge-shaped oligopeptide, even after 7-min potential application.13 To our knowledge, this is the first description of an oligopeptide-based electrochemical cell detachment platform that allows complete cell retrieval in minutes.

The cell-adhesive oligopeptide contains the cell-anchoring sequence, GRGDSP, which forms a β-turn structure30 and could create a bulkier peptide than the cell-repulsive oligopeptide, as illustrated in Figure 1D. We had expected that when the cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive oligopeptides are mixed at a certain ratio, a denser SAM may form that would accelerate cell detachment. To this end, we prepared solutions containing mixtures of the cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive oligopeptides at ratios of 10:90 and 1:99. However, cells detached from both the compositions within 2 min, similar to the kinetics observed on using 100% cell-adhesive oligopeptide. Optimization of the oligopeptide sequence, such as by varying the lengths of the alternating KE and GGG spacer, might provide a well-defined structure and closely packed monolayer.31 In future investigations, we will focus on the design of SAM with shorter cell detachment times.

Electrochemical detachment of cell sheets

Cell sheet engineering is a promising approach in the field of regenerative medicine.32 We therefore examined whether zwitterionic oligopeptide substrates might be useful for engineering cell sheets. To do this, we examined adhesion of hBMSCs, which have great potential as a cell source for tissue regeneration in humans.33 hBMSCs were cultured on gold surfaces modified with the cell-adhesive oligopeptide for 3 days until the cells had formed confluent monolayers. The cell sheets were then coated with a collagen gel layer, and −1.0 V was applied for 5 min, after which the detached cell sheet was peeled off with the gel layer (Fig. 5A). The cell sheets were stained with fluorescent probes to discriminate live (FDA, green) and dead (EB, red) cells, which showed that almost all the cells in the harvested cell sheets were viable (Fig. 5B). This electrochemical cell detachment process is very rapid compared to other approaches, for example, thermoresponsive surfaces, which typically require 40–60 min for cell detachment.8,34 This feature will be particularly beneficial to maintain cell viability when cell sheets are stacked during fabrication of multilayered cell sheets for transplantation.

FIG. 5.

Electrochemical transfer of cell sheets and micropatterned cells to collagen gels. (A) Detached human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell (hBMSC) sheet. (B) Live/dead fluorescent staining of the detached hBMSC sheets: green indicates live cells, and red indicates dead cells. (C) Procedure for micropatterning of the two oligopeptides. (D) Stamped fluorescein patterning. Fibroblasts adherent on the micropatterned surface at 3 h (E), 1 day (F), and 2 days (G) of culture and on striped pattern at 1 day (H) and 2 days (I) of culture. (J) Human umbilical vein endothelial cells constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP-HUVECs) on striped micropatterns at 3 h of culture. GFP-HUVECs transferred to collagen gels and cultured for 1 (K), 2 (L), and 3 days (M). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Micropatterning and transfer of cells from the gold surface to collagen gels

We used micropatterning to create gold substrates modified with spatially controlled patterns of cell-adhesive and cell-repulsive oligopeptides (Fig. 5C). Cell-adhesive islands were first prepared with microcontact printing of the cell-adhesive oligopeptide, and the remaining regions were then modified with the cell-repulsive oligopeptide (Fig. 5C). Figure 5D shows a stamped pattern visualized with fluorescein. Fibroblasts seeded on the patterned surfaces selectively adhered to the islands containing the cell-adhesive oligopeptide (Fig. 5E). After 1 day of culture, most of the cells were confined to these adhesive regions, and only a few cells had migrated into the region containing the cell-repulsive oligopeptide (Fig. 5F). However, after 2 days of culture, a significant number of cells had randomly migrated over the entire surface, and the patterns virtually disappeared (Fig. 5G). This phenomenon was independent of the pattern geometry, and was also observed when the oligopeptides were applied in a striped pattern (Fig. 5H, I). These results suggest that the cell-repulsive oligopeptide inhibited the initial cell adhesive events, but did not block cell migration over a sustained period. We therefore examined the long-term stability of the bound cell-repulsive oligopeptide. The surface modified with the cell-repulsive oligopeptide was exposed to the culture medium containing 10% FBS for 24 h, and the amount of adsorbed protein was then quantified using QCM. We found that the surface coated with the cell-repulsive oligopeptide effectively prevents adsorption of proteins even after 24 h, suggesting that the oligopeptide remained attached on the surface (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that there may be some oligopeptide SAM instability or contamination with other molecules, especially in the presence of cells, which may induce oligopeptide degradation or overlay of adhesive proteins on the SAM. Further investigation using real-time QCM or atomic-force microscopy will be necessary to clarify this.

We next determined whether cell micropatterns can be transferred to a hydrogel. As previously, micropatterned oligopeptides were applied to the gold surface; GFP-HUVECs were allowed to adhere; and a collagen layer was overlaid. A potential of −1.0 V was applied for 5 min, and the gel layer with detached cells was removed. The striped micropattern of adherent cells (Fig. 5J) was transferred to the hydrogel (Fig. 5K). The transferred HUVECs maintained their activity of network assembly as is typically observed in conventional collagen gel culture (Fig. 5L, M).35 Collectively, these results demonstrate the noninvasive electrochemical transfer of cells from modified substrates to collagen gels. This process has the potential for rapid fabrication of complex tissues in a spatially controlled manner for tissue-engineering applications.

Conclusions

Custom-designed zwitterionic oligopeptides spontaneously formed SAMs on gold surfaces via gold–thiolate bonds and intermolecular electrostatic forces. The SAMs of cell-repulsive oligopeptides significantly decreased nonspecific protein adsorption and cell adhesion, whereas cell attachment and growth were supported by SAMs formed with >1% cell-adhesive oligopeptide. Adherent cells were completely detached from these surfaces within 2 min by applying a negative electrical potential. Furthermore, the difference in the ability of the two oligopeptide SAMs to support cell adhesion allowed fabrication and transfer of cell micropatterns to a hydrogel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A), 20686056; Grant-in-Aid for challenging Exploratory Research, 22656167]; and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (H20-Saisei-wakate-010 and H22-Saisei-wakate-002).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Langer R. Tirrell D.A. Designing materials for biology and medicine. Nature. 2004;428:487. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillaume-Gentil O. Gabi M. Zenobi-Wong M. Voros J. Electrochemically switchable platform for the micro-patterning and release of heterotypic cell sheets. Biomed Microdevices. 2011;13:221. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elloumi-Hannachi I. Yamato M. Okano T. Cell sheet engineering: a unique nanotechnology for scaffold-free tissue reconstruction with clinical applications in regenerative medicine. J Intern Med. 2010;267:54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyahara Y. Nagaya N. Kataoka M. Yanagawa B. Tanaka K. Hao H., et al. Monolayered mesenchymal stem cells repair scarred myocardium after myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 2006;12:459. doi: 10.1038/nm1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohashi K. Yokoyama T. Yamato M. Kuge H. Kanehiro H. Tsutsumi M., et al. Engineering functional two- and three-dimensional liver systems in vivo using hepatic tissue sheets. Nat Med. 2007;13:880. doi: 10.1038/nm1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishida K. Yamato M. Hayashida Y. Watanabe K. Yamamoto K. Adachi E., et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of autologous oral mucosal epithelium. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang Z.L. Akiyama Y. Yamato M. Okano T. Comb-type grafted poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) gel modified surfaces for rapid detachment of cell sheet. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7435. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon O.H. Kikuchi A. Yamato M. Sakurai Y. Okano T. Rapid cell sheet detachment from poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-grafted porous cell culture membranes. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<82::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo W.S. Mrksich M. Electroactive self-assembled monolayers that permit orthogonal control over the adhesion of cells to patterned substrates. Langmuir. 2006;22:10816. doi: 10.1021/la061212y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillaume-Gentil O. Akiyama Y. Schuler M. Tang C. Textor M. Yamato M., et al. Polyelectrolyte coatings with a potential for electronic control and cell sheet engineering. Adv Mater. 2008;20:560. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M. Lee J.Y. Shah S.S. Tae G. Revzin A. On-cue detachment of hydrogels and cells from optically transparent electrodes. Chem Commun. 2009;39:5865. doi: 10.1039/b909169f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda J. Kameoka Y. Suzuki H. Spatio-temporal detachment of single cells using microarrayed transparent electrodes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6663. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seto Y. Inaba R. Okuyama T. Sassa F. Suzuki H. Fukuda J. Engineering of capillary-like structures in tissue constructs by electrochemical detachment of cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2209. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadr N. Zhu M.J. Osaki T. Kakegawa T. Yang Y.Z. Moretti M., et al. SAM-based cell transfer to photopatterned hydrogels for microengineering vascular-like structures. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7479. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inaba R. Khademhosseini A. Suzuki H. Fukuda J. Electrochemical desorption of self-assembled monolayers for engineering cellular tissues. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3573. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mochizuki N. Kakegawa T. Osaki T. Sadr N. Kachouie N.N. Suzuki H., et al. Tissue engineering based on electrochemical desorption of an RGD-containing oligopeptide. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. doi: 10.1002/term.519. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbosa J.N. Barbosa M.A. Aguas A.P. Inflammatory responses and cell adhesion to self-assembled monolayers of alkanethiolates on gold. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2557. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbosa J.N. Barbosa M.A. Aguas A.P. Adhesion of human leukocytes to biomaterials: an in vitro study using alkanethiolate monolayers with different chemically functionalized surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;65A:429. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray D.W.R. Morris P.J. The use of fluorescein diacetate and ethidium-bromide as a viability stain for iIsolated islets of langerhans. Stain Technol. 1987;62:379. doi: 10.3109/10520298709108028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrksich M. Whitesides G.M. Using self-assembled monolayers to understand the interactions of man-made surfaces with proteins and cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S.F. Cao Z.Q. Jiang S.Y. Ultra-low fouling peptide surfaces derived from natural amino acids. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5892. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widrig C.A. Chinkap C. Porter M.D. The electrochemical desorption of n-alkanethiol monolayers from polycrystalline Au and Ag electrodes. J Electroanal Chem. 1991;310:335. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howson S.E. Bolhuis A. Brabec V. Clarkson G.J. Malina J. Rodger A. Scott P. Optically pure, water-stable metallo-helical ‘flexible’ assemblies with antibiotic activity. Nat Chem. 2012;4:31. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostuni E. Chapman R.G. Holmlin R.E. Takayama S. Whitesides G.M. A survey of structure-property relationships of surfaces that resist the adsorption of protein. Langmuir. 2001;17:5605. doi: 10.1021/la0015258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts C. Chen C.S. Mrksich M. Martichonok V. Ingber D.E. Whitesides G.M. Using mixed self-assembled monolayers presenting RGD and (EG)(3)OH groups to characterize long-term attachment of bovine capillary endothelial cells to surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6548. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houseman B.T. Mrksich M. The microenvironment of immobilized Arg-Gly-Asp peptides is an important determinant of cell adhesion. Biomaterials. 2001;22:943. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prime K.L. Whitesides G.M. Self-assembled organic monolayers: model systems for studying adsorption of proteins at surfaces. Science. 1991;252:1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prime K.L. Whitesides G.M. Adsorption of proteins onto surfaces containing end-attached oligo(ethylene oxide)—a model system using self-assembled monolayers. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:10714. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munakata H. Oyamatsu D. Kuwabata S. Effects of ω-functional groups on pH-dependent reductive desorption of alkaenthiol self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir. 2004;20:10123. doi: 10.1021/la048878h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson W.C. Pagano T.G. Basson C.T. Madri J.A. Gooley P. Armitage I.M. Biologically active Arg-Gly-Asp oligopeptides assume a type II β-turn in solution. Biochemistry. 1993;32:268. doi: 10.1021/bi00052a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowinski A. Sun F. White A. Keefe A. Jiang SY. Sequence, structure, and function of peptide self-assembled monolayers. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6000. doi: 10.1021/ja3006868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J. Yamato M. Shimizu T. Sekine H. Ohashi K. Kanzaki M., et al. Reconstruction of functional tissues with cell sheet engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5033. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guillaume-Gentil O. Semenov O.V. Zisch A.H. Zimmermann R. Voros J. Ehrbar M. pH-controlled recovery of placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell sheets. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4376. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon O.H. Kikuchi A. Yamato M. Okano T. Accelerated cell sheet recovery by co-grafting of PEG with PIPAAm onto porous cell culture membranes. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1223. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montanez E. C-MR P. Vilaro S. Pagan R. Comparative study of tube assembly in three-dimensional collagen matrix and on Matrigel coats. Angiogenesis. 2002;5:167. doi: 10.1023/a:1023837821062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.