Abstract

Compared to benzoporphyrin derivative-dimethyl ester (BPD-DME) and its 8-(1′-hexyloxy)ethyl analog the corresponding In(III) complexes showed enhanced in vitro photosensitizing efficacy in Colon26 tumor cells, which could be due to their higher singlet oxygen producing ability. In both organic (methanol) and aqueous Bovine Calf Serum (17% BCS) solutions the metalated analogs were significantly more stable than the parent photosensitizers. Presence of Indium as a central metal gave 13–25 nm hypsochromic shift to the long wavelength absorption band with reduced absorption and fluorescence intensity. The insertion of metal did not produce any difference in intracellular localization of the photosensitizers and were mainly localized in mitochondria.

Keywords: BPD, photosensitizer, metalated, photodynamic therapy

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, a large number of long wavelength absorbing compounds have been evaluated for photodynamic therapy efficacy [1–3]. One such photosensitizer, which has shown limited skin phototoxicity, is benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD) [4], and it has already been approved for the treatment of age related macular degeneration (AMD) by PDT [5]. However, it shows low tumor specificity and retains in tumor only for a short time. In previous studies with series of chlorophyll, phthalocyanines, porphycene and texaphyrin derivatives, it has been shown that overall lipophilicity of the molecules makes a significant difference in in vivo efficacy [6]. Although lipophilicity plays an important role in drug development [7], it is imperative to have a hydrophobic matrix, which could allow drug interaction through the cell membrane. Among a series of alkyl ether analogs of pyropheophorbide-a (a chlorophyll derivative), we have shown that besides the overall lipophilicity, the position of the substituents at the periphery of the molecule also plays an important role in PDT efficacy [8–10]. A quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) of a series of 3-(1′-alkoxy)ethyl analogs of pyropheophirbide-a [11] showed a parabolic relationship between the overall lipophilicity and PDT efficacy and among the compounds investigated, the hexyl ether analog (HPPH) was most effective, which is currently in Phase II human clinical trials [11–14]. To investigate the impact of central metal in PDT efficacy, we investigated the PDT efficacy of a series of metal analogs. Among these analogs the In(III) HPPH complex produced remarkable improvement in long-term PDT response [15, 16].

To establish generic requirements for an effective photosensitizer, we were interested in incorporating these modifications to BPD dimethyl ester and investigating the biological efficacy of the resulting products. On the basis of our previous finding, we hypothesized that the replacement of the vinyl group at position-8 with 1′-hexyloxyethyl chain and insertion of Indium as a central metal should enhance the photosensitizing ability of the parent molecules. To investigate the utility of our approach, the metalated and free base compounds of BPD dimethyl ester and BPD hexyl ether were synthesized by following the methodology established in our laboratory [9] and the resulting products were evaluated for in vitro photosensitizing efficacy.

EXPERIMENTAL

All photophysical experiments were carried out using spectroscopic grade solvents. The reactions were monitored by TLC and/or spectrophotometrically. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was done on ANALTECH pre-coated silica gel GF PE sheets (Cat. 159017, layer thickness 0.25 mm). Column chromatography was performed over Silica Gel 60 (70–230 mesh). In some cases preparative TLC plates were also used for the purification (ANAL-TECH precoated silica gel GF glass plate, Cat. 02013, layer thickness 1.0 mm). The synthetic intermediates and the final products were characterized by NMR (400 MHz) and mass spectrometry (EIMS or HRMS). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX 400 MHz spectrometer at 303 K in CDCl3 solution and referenced to residual CHCl3 (7.26 ppm). EI-mass spectra were carried out on a Brucker Esquire ion-trap mass spectrometer equipped with a pneumatically assisted electrospray ionization source, operating in positive mode. UV-visible spectra were recorded on Varian Cary 50 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer using dichloromethane or methanol as solvent.

8-vinylbenzoporphyrin indium(III) chloride derivative 3

In a 100 mL reaction flask, BPD 1 (50.0 mg) was dissolved in 15 mL toluene and sodium acetate (500 mg), anhydrous K2CO3 (500 mg) and indium(III) chloride (300 mg) were added. The reaction mixture was refluxed under argon for 12 h. The progress of reaction was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy. The reaction mixture was neutralized with acetic acid, and washed with water (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. The solvents were then removed under high vacuum at room temperature. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography using 5% methanol-dichloromethane as mobile phase to give the title compound 3 in 30% yield. UV-vis (CH3OH): λmax, nm (ε × 104 ) 655 (2.76). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ, ppm 9.82 and 9.78 (each s, 1 H, meso-H), 9.28 and 8.82 (each s, 1 H, meso-H), 8.09 (m, 1 H, CH=H2), 7.78 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0, CH=H), 7.42 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0, CH=CH), 6.24 (d, 1 H, J = 16, CH=H2), 6.18 (d, 1 H, J = 12, CH=CH2), 5.06 (s, 1 H, CHCO2Me), 4.50 and 4.44 (each t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 4.20, 3.86, 3.66, 3.64, 3.50, 3.42, 2.94 and 1.80 (each s, 3 H, Me and OMe), 3.19 and 3.21 (each t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO, Me). EIMS: m/z 846 [MH+ – Cl].

8-vinylbenzoporphyrin indium(III) acetate derivative 4

The title compound was obtained by reacting BPD 1 (60 mg) with indium(III) acetate (300 mg), using the procedure described above gave 33% of the title compound 4. UV-vis (CH3OH): λmax, nm (ε × 104) 656 (2.76). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ, ppm 9.80 and 9.76 (each s, 1 H, meso-H), 9.20 and 8.78 (each s, 1 H, meso-H), 8.07 (m, 1 H, CH=H2), 7.76 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0, CH=H), 7.39 (d, 1 H, J = 6.0, CH=CH), 6.21 (d, 1 H, J = 16, CH=H2), 6.19 (d, 1 H, J = 12, CH=CH2), 5.05 (s, 1 H, CHCO2Me), 4.50 and 4.44 (each t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 4.20, 3.86, 3.66, 3.64, 3.50, 3.42, 2.94 and 1.80 (each s, 3 H, Me and OMe), 3.20 (m, 4 H, CH2CH2CO, Me). EIMS: m/z 846 [MH+ – OAc].

8-(1′-hexyloxyethyl)benzoporphyrin indium(III) chloride derivative 5

In a 100 mL reaction flask, BPD hexyl derivative 2 (60.0 mg) was dissolved in 15 mL toluene, and sodium acetate (500 mg), anhydrous K2CO3 (500 mg) and indium(III) chloride (300 mg) were added. The reaction mixture was refluxed under argon for 12 h. The reaction was monitored to completion by UV-vis spectroscopy. The reaction mixture was neutralized with acetic acid, and washed with water (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over sodium sulfate. The solvents were then removed under high vacuum at room temperature. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography using 5% methanol-dichloromethane as mobile phase to give the title compound 5 in 32% yield. UV-vis (CH3OH): λmax, nm (ε × 104) 658 (2.31). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ, ppm 9.75, 9.68, 9.26 and 8.84 (each s, total 4 H, meso-H), 7.78 and 7.49 (each d, 1 H, J = 6.4, MeCO2C=CHCH), 5.96 [q, 1 H, J = 6.0, CH(CH3)O], 5.04 (s, 1 H, CHCO2Me), 4.30 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 4.04 (s, 3 H, Me), 4.18 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2-CO2Me), 3.43–3.85 (each s, total 28 H, Me, OMe), 3.21 (m, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 3.14 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 0.72–2.04 [m, total 19 H, Me and (CH2)5Me]. EIMS: m/z 948 [MH+ – Cl].

8-(1′-hexyloxyethyl)benzoporphyrin indium(III) acetate derivative 6

The title compound was obtained by reacting BPD hexyl ether 2 (60 mg) with indium(III) acetate (300 mg), using the procedure described above gave 35% of derivative 6. UV-vis (CH3OH): λmax nm (ε × 104) 661 (2.76). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ, ppm 10.18, 9.77, 9.30 and 8.84 (each s, total 4 H, meso-H), 7.78 and 7.48 (each d, 1 H, J = 6.4, MeCO2C=CHCH), 5.96 [q, 1 H, J = 6.0, CH(CH3)O], 5.04 (s, 1 H, CHCO2Me), 4.30 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 4.04 (s, 3 H, Me), 4.18 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 3.43–3.85 (each s, total 28 H, Me, OMe), 3.21 (m, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 3.14 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2CO2Me), 0.72–2.04 [m, total 19 H, Me and (CH2)5Me]. EIMS: m/z 948 [MH+ – OAc].

In vitro PDT and cell viability assay

Colon26 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Colon26 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5.0 × 103 cells per well in complete medium. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, photosensitizers were added at variable concentrations for 24 h in the dark. The medium that contained the photosensitizers was replaced with fresh medium. The cells were illuminated with a halogen light at 400 to 700 nm with various fluence rates (1–4 J/cm2). After light exposure, the cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in the dark and the phototoxicity was determined by the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay [18]. Dose response cell survival curves were generated using Microsoft Excel software.

In vitro photobleaching

For each photosensitizer, 5 μM solution was prepared separately in 17% fresh FBS and in methanol separately. The prepared solutions were irradiated under similar light exposure (75 mW/cm2) at various times points in a cuvette. After each time point the rate of photobleaching for each solution was measured by absorption spectrometry. The absorption at the variable time points for each photosensitizer (prepared drug solution) were recorded and plotted by using Microsoft Excel Software.

Co-localization of photosensitizers using AMNIS® image stream cytometry

Colon26 cells were seeded in six well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells per well in complete medium. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, photosensitizers were added at 0.50 μM for 24 h in the dark at 37 °C with Fluospheres (1/10000 dilution of stock, for lysosome staining). Prior to harvesting, cells were incubated with Mitotracker Red (5 nM, for mitochondrial staining) for 15 min at 37 °C. Cell were harvested and re-suspended in 60 μL of PBS containing 2% FBS. Each sample was transferred to 1.5 mL siliconized microfuge tubes and samples were processed using the AMNIS® Image Stream Cytometry. For compensation, single color controls were made for Fluospheres, Mitotracker Red, and each photosensitizer. All prepared samples were kept over ice. For analysis of data the IDEAS® software was used for determination of co-localization.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

BPD dimethyl ester was a gift from Professor David Dolphin, QLT, Vancouver, Canada. It was converted into the corresponding hexyl ether derivative and In(III) analogs.

In general the efficiency of indium insertion in porphyrin core is quite high yielding the resulting product(s) in the range of 70 to 80%. However, the conversion of BPD dimethyl ester derived from protoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester to the corresponding indium analog was only 30%, which could be due to a drastic change in the planarity of the tetrapyrrolic skeleton. The structures of the free base and the corresponding metalated analogs were confirmed by NMR and mass spectrometry analyses. The BPD dimethyl ester has its long wavelength absorption at 680 nm (emission: 690 nm). Conversion of the vinyl group with (1′-hexyloxyethyl) group exhibited a hypsochromic shift of 6 nm and the long wavelength absorption was observed at 674 nm (emission: 688 nm), which showed further blue shift of 5 nm on converting these compounds to the corresponding indium analogs 3 and 5 with significantly reduced fluorescence. The electronic absorption spectra of photosensitizers 1, 2, 3, 5 at equimolar concentrations are illustrated in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

(a) Synthesis, (b) electronic absorption and (c) fluorescence spectra of BPD analogs

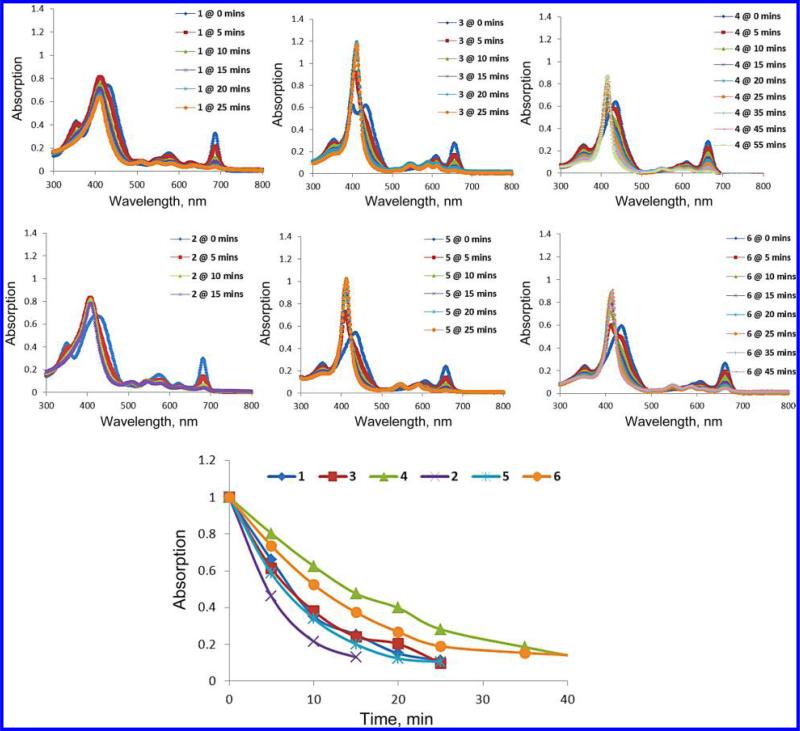

It has been well-established that three critical elements are required for the initial photodynamic processes to occur: a drug that can be activated by light, light with an appropriate wavelength and oxygen. The stability of photosensitizer during the light treatment could also play an important role in enhancing the PDT efficacy. Therefore, the rate of photobleaching of the free base and the corresponding metalated analogs during the light exposure was investigated in both organic and physiological conditions. To test photostability, a 17% solution of Bovine Calf Serum in PBS was made to maximal dis-aggregation replicating physiological conditions when undergoing treatment. The 5 μM solutions of all compounds were made and individually tested for stability. However, in in vitro photostability testing, as in the phototoxicity studies, BPD-DME had poor aqueous solubility and was not tested in Bovine Calf Serum. To compensate, the BPD-ma was used. When tested, the compound solution was placed to a 3 cm height in a fluorescence spectrophotometer cell. The solution was placed under magnetic stir at a constant rate and at a constant distance of 14 cm away from the laser tip. The solution was then irradiated with a 75 mW/cm2 laser light and the rate of photobleaching at variable time points were recorded. From the results summarized in Figs 1 and 2, it can be seen that compared to free base the corresponding metalated analogs were significantly more stable. As expected, replacing the vinyl group in BPD dimethyl ester 1 with 1′-hexyloxyethyl group 2 did not make any significant difference in the rate of photobleaching.

Fig. 1.

The rate of photobleaching of the free base vs. metalated photosensitizers in 17% aqueous Bovine Calf Serum (BCS)

Fig. 2.

The rate of photobleaching of the free base 1, 2 vs. metalated 3–6 photosensitizers in methanol

In vitro photosensitizing efficacy

The photosensitizing efficiencies of BPD dimethyl ester, the hexyl ether analog 2 and the corresponding In(Cl) and In(OAc) were investigated by MTT assay in Colon26 tumor cells at 24 h post-incubation. The photosensitizing efficacy of these photosensitizers was compared at various concentrations (0.001562 μM, 0.003125 μM, 0.00625 μM, 0.0125 μM, 0.025 μM, 0.05 μM, 0.1 μM, 0.2 μM, 0.4 μM, and 0.8 μM). In brief, the cells were incubated with the compounds for 24 h at 37.5 °C in CO2. After 24 h, the cells were irradiated with various light doses (0.5 J, 1 J, 2 J, and 4 J/cm2) to deliver the required light fluency. After treatment, new media was added to all plates including the dark plate used as the control. The cells were incubated for 48 h before the MTT assay was conducted. To confirm the results, this process was repeated two more times under the same conditions. As can be seen, the metalated analogs of both the dimethyl ester and the hexyl ether derivatives showed more phototoxicity in comparison to their corresponding free base compounds. With regards to the counter ions, there was little to no difference in cell death induced by either the In(III)Cl or the In(III)OAc analogs. The in vitro phototoxicity results are summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

In vitro photosensitizing efficacy of BPD analogs 1–6 at variable concentrations. The Colon-26 tumor cells were exposed to light 2 J/cm2 at 24 h postincubation of the photosensitizers, and the MTT assay was performed after 24 h. None of these compounds showed any dark toxicity: drug alone, no light exposure (data not shown)

Intracellular localization

By using fluorescence or confocal microscopy it has been shown that BPD monocarboxylic acid localizes in mitochondria. To investigate the impact of the corresponding dimethyl ester and its hexyl ether and metalated analogs in site of localization of BPD dimethyl ester 1, the corresponding hexyl ether analog 2 and the respective In(III)Cl complexes 3 and 5 respectively was investigated in Colon26 cells with mitochondrial and lisosomal probes. The fluorescence images of the photosensitizer, mitochondrial probe and the merged images are shown in Fig. 4. As can be seen, the increasing the overall hydrophobicity of the molecule or insertion of indium as central metal did not make any significant difference in site of localization of the photosensitizer. None of these photosensitizers show any specificity to lysosomes and these results are incorporated in the Supporting information section of the manuscript.

Fig. 4.

Comparative intracellular localization (false color images) of BPD dimethyl ester (BPD-DME) 1, hexyl ether derivative of BPD-DME 2, In(III)Cl of BPD-DME 3 and In(III) Cl of hexyl ether derivative of BPD-DME 5 with MtoTracker Red (mitochondrial probe) in Colon26 cells after incubation for 24 h clearly shows mitocondrial localization of all the analogs

CONCLUSION

The replacement of the vinyl group present at position-8 with the 1′-hexyloxyethyl group showed a slight increase in in vitro PDT efficacy. However, conversion of these analogs to the corresponding indium derivatives produced a significant increase in PDT efficacy. These results are similar to those reported in PDT agents derived from pyropheophorbide-a. As reported previously, the enhanced PDT efficacy of these agents could be due to their longer life of excited triplet state resulting to higher singlet oxygen generating abilities, a key cytotoxic agent for PDT. These compounds are currently being evaluated for detailed in vivo, tumor uptake, PDT efficacy at variable drug /light doses and these results will be published in a biological journal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Janet Morgan for her help in localization studies. The financial support from NIH (CA 55791), CA55791S (Supplemental funds) and the shared resources of the RPCI Support Grant (P30CA16056) is highly appreciated.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor Karl M. Kadish on the occasion of his 65th birthday

Supporting information

Supplementary material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://www.worldscinet.com/jpp/jpp.shtml.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ethirajan M, Chen Y, Joshi P, Pandey RK. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:340–362. doi: 10.1039/b915149b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandey RK, Goswami LN, Chen Y, Gryshuk A, Missert JR, Oseroff A, Dougherty TJ. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006;38:445–467. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternberg ED, Dolphin D, Bruckner C. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4151–4202. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter AM, Kelly B, Chow J, Liu DJ, Powers GHN, Dolphin D, Levy JG. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1987;79:1327–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan EH. US Sensory Disord. 2006:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandey RK, Zheng G. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 6. Academic Press; 2000. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey RK, Sumlin AB, Potter WR, Bellnier DA, Henderson BW, Constantine M, Aoudia M, Rodgers MR, Smith KM, Dougherty TJ. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996;63:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandey RK, Bellnier DA, Smith KM, Dougherty TJ. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991;53:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb08468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey RK, Sumlin A, Shiau F-Y, Dougherty TJ, Smith KM. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 1992;2:491–494. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey RK, Mettath SK, Gupta S, Dougherty TJ, Smith KM. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 1995;5:860–867. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson BW, Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Sharma A, Pandey RK, Vaughan LA, Weishaupt KR, Dougherty TJ. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4000–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty TJ, Pandey RK, Nava H, Smith JA, Douglass HO, Edge SB, Bellnier DA, Cooper M. Proc. SPIE. 2000;3909:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Loewen GL, Nava H, Oseroff A, Pandey RK, Dougherty TJ. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1806–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loewen GM, Pandey RK, Bellnier DA, Henderson BW, Dougherty TJ. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006;38:364–370. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Che Y, Zheng X, Dobhal MP, Gryshuk A, Morgan, Dougherty TJ, Pandey RK. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:3692–3695. doi: 10.1021/jm050039k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenfeld A, Morgan J, Goswami LN, Zheng X, Ohulchanskyy T, Prasad PN, Pandey RK. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006;82:626–634. doi: 10.1562/2005-09-29-RA-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srivatsan A, Ethirajan M, Pandey SK, Dubey S, Zheng X, Liu T-H, Shibata M, Missert J, Morgan J, Pandey RK. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2011;8:1186–1197. doi: 10.1021/mp200018y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessel D, Reiners JJ. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007;83:1024–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessel D, Vicente MG, Reiners JJ. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006;38:482–488. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessel D, Oleinick NL. In: Photodynamic Therapy, Methods and Protocols. Gomer CJ, editor. Springer; New York: 2010. Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.