Abstract

SINEBase (http://sines.eimb.ru) integrates the revisited body of knowledge about short interspersed elements (SINEs). A set of formal definitions concerning SINEs was introduced. All available sequence data were screened through these definitions and the genetic elements misidentified as SINEs were discarded. As a result, 175 SINE families have been recognized in animals, flowering plants and green algae. These families were classified by the modular structure of their nucleotide sequences and the frequencies of different patterns were evaluated. These data formed the basis for the database of SINEs. The SINEBase website can be used in two ways: first, to explore the database of SINE families, and second, to analyse candidate SINE sequences using specifically developed tools. This article presents an overview of the database and the process of SINE identification and analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Short interspersed elements (SINEs) are mobile genetic elements invading genomes of most higher eukaryotes (exceeding 10% of some genomes). Although these genomic parasites can be deleterious to the cell, the long-term being in the genome has made SINEs a valuable factor of genetic variation, providing regulatory elements for gene expression, alternative splice sites, polyadenylation signals and even functional RNA genes (1–4). At the same time, the system and nomenclature of SINEs remain to a large extent unarticulated. SINEBase is a manually curated database of SINE families known to date. It aims to be a resource for scientists working on mobile elements as well as for a wide range of biologists analysing nucleic acid sequences. SINEBase can be considered as a compendium of SINEs; its toolset allows individual SINE sequences to be attributed to known SINE families and/or analysed.

Definitions

Retro(trans)posons are genetic elements that can amplify themselves in eukaryotic genomes, which requires an RNA intermediate, and thus, transcription and reverse transcription. Retrotransposons are divided into three classes: long terminal repeat (LTR) elements, long interspersed elements (LINEs) and SINEs. The elements that encode the enzyme activities, providing for the reverse transcription and integration of the DNA copy into the genome, are called autonomous transposons. Nonautonomous retroposons rely on the enzyme machinery of autonomous transposons. LTR retrotransposons and LINEs can be autonomous or nonautonomous; and their genomic copies are transcribed by the cellular RNA polymerase II (5,6).

SINEs are defined as relatively short (<700 bp) nonautonomous retroposons transcribed by the cellular RNA polymerase III (pol III) from an internal promoter, whereas their reverse transcription depends on the reverse transcriptase of partner LINEs. Eukaryotic genomes can harbor hundreds thousands (sometimes more) of SINE copies; copies originating from a common ancestral SINE can differ from each other by single-nucleotide alterations as well as by longer internal deletions or duplications (SINEs with such duplication are called quasidimeric). Some of them can become founders of new SINE subfamilies.

SINEs consist of two or more modules; typically, head, body and tail. The 5′-terminal head originates from one of cellular RNAs synthesized by pol III: tRNA, 7SL RNA or 5S rRNA. The origin of the body is either unknown or it descends from a partner LINE. SINEs with such a region mimic LINE RNA in the reverse transcription (7). The body can also contain a central domain shared by distant SINE families (CORE and similar domains). The 3′-terminal tail is a sequence of variable length consisting of simple (often degenerate) repeats. In addition, two SINEs can combine into a dimeric SINE, thus, giving rise to a new SINE family. SINEs consisting of the head and tail only are called simple, whereas dimeric, trimeric, etc. are complex SINEs. Various aspects of SINE structure, biology and evolution have been reviewed elsewhere (4,8,9).

We consider SINEs as (i) short (<1 kb) interspersed (nontandem) genomic repeats; (ii) present in at least 100 copies per genome (except certain genomes where repetitive elements are not abundant, e.g. Arabidopsis thaliana); (iii) with at least 60% identity with a tRNA species (10), 5S rRNA or 7SL RNA in at least 60-nt overlap (with a few exceptions where the element transcription by pol III was confirmed experimentally). We found that pol III promoters (e.g. boxes A and B) can serve only as an indication (but not a proof) that the sequence belongs to SINEs. (Even when more sophisticated methods of pol III promoter identification, e.g. with position frequency matrices, were used, the proportion of false positives and/or misses remained high for different ‘stringency’ values). SINEs should be distinguished from RNA pseudogenes: the pseudogenes are generated by the reverse transcription of the functional RNAs of cellular origin (e.g. 5S rRNA) rather than of SINE RNAs transcribed from their genomic copies. In practical terms, most SINEs have extra (body) sequences, whereas simple SINEs have characteristic substitutions/indels shared with their source gene but not with the cellular RNA gene. In addition, SINEs significantly outnumber RNA pseudogenes.

The notion of ‘SINE family’ is widely used but not clearly defined. We consider SINE family as a set of SINEs (i) of a common origin and (ii) consisting of the same modules (except the tail, which can vary even in the same species). Thus, similar SINEs with different LINE-derived regions (e.g. mammalian Ther-2 and Mar-1) belong to different families. Long insertions are considered as modules. At the same time, internal deletions or duplications within modules do not give birth to a new family; although a combination of complete or almost complete SINEs (complex SINEs) is considered as a new family (thus, pB1 and quasidimeric B1 are subfamilies of the same family, whereas dimeric Alu represents a distinct family). Finally, there are а few SINEs with similar structure but of independent origin (e.g. simple SINEs: ID in rodents, vic-1 in camels and DAS-I in armadillos), thus, considered as different families.

DATABASE OF SINE FAMILIES

Data acquisition

We extracted consensus sequences of SINE families largely from two sources, original publications and the Repbase Update (RU; ver. 16.07) database (11). In many cases, they were refined in the available sequence databases. The consensus sequences were compared with the sequences of other SINEs, LINEs, tRNA species, 5S rRNA and 7SL RNA to identify their modules. Similar sequences were aligned and the differences were analysed. The elements composed of the same modules were considered as the same SINE family. There were particularly knotty cases, e.g. the CHRS family. This SINE is a quasioligomer, it contains a ∼20-nt degenerate motif, which can be tandemly repeated more than 10 times. The variants differing in the number of these repeats were previously recognized as different SINE families (CHRS, CHR-2, CHRL, etc.). Multiple alignments clarifying such cases can be found in Supplementary Alignments S1. As a result, 175 SINE families were recognized according to the above definitions.

SINEBase organization

The heart of the database is the SINETable (also available as Supplementary Table S1) visualizing the main data about all SINE families known to date (length, distribution, copy number, schematic structure, etc.). The table contents can be limited to certain taxa and sorted by some characters (e.g. tail sequence). It contains links to SINE family-specific data (e.g. consensus sequence or publications) or to term descriptions. The databases of consensus sequences of SINE families, central domains and LINE-derived regions can be downloaded in the Download section, whereas individual consensus sequences and the multiple alignments are accessible as Supplementary Sequences S1 and Supplementary Alignments S2 and S3, respectively.

SINEBase tool

Based on our long-term experience in SINE analysis, we offer a toolset for the identification of SINE families and modules (SINESearch). This tool can also ascertain that the sequence of interest is not a SINE or that it belongs to an unknown SINE family. In the latter case, SINESearch can be used to analyse the modules of a new SINE.

It is a FASTA-based search that uses parameters other than the FASTA’s statistical significance test to select sequences. This obviates two limitations of FASTA (as well as BLAST etc.) in the case of relatively short and degenerate similarities between nucleotide sequences: a bias to short (almost) perfect matches, whereas the goal is full-length and significant similarities; and missing significant hits when the bank includes many sequences similar to query. The search banks include our collections of full-length SINEs and their modules (certain RNAs, central domains and LINE-derived regions).

SINESearch is simple to use and fast. The search parameters used, overlap length and sequence identity, are biologically sensible and allow easy adjustment of hit selection. Query sequence can be manually input or uploaded. SINESearch offers four banks: SINEBank (consensus sequences of SINE families), RNABank (human tRNA species (10) plus 7SL RNA and 5S rRNA), LINEBank (SINE consensus sequences derived from partner LINEs) and COREBank [consensus sequences of central (CORE, Deu-, V-, Ceph-, α- and β-) domains].

The recommended protocol for the analysis of putative SINE sequences (explained in detail in the Help section) includes the following steps: preliminary analysis of a sequence of interest to exclude non-SINE sequences; SINESearch against the SINEBank to identify SINEs that belong to known SINE families and SINESearch against other banks to identify individual modules of a putative SINE.

SINE data analysis

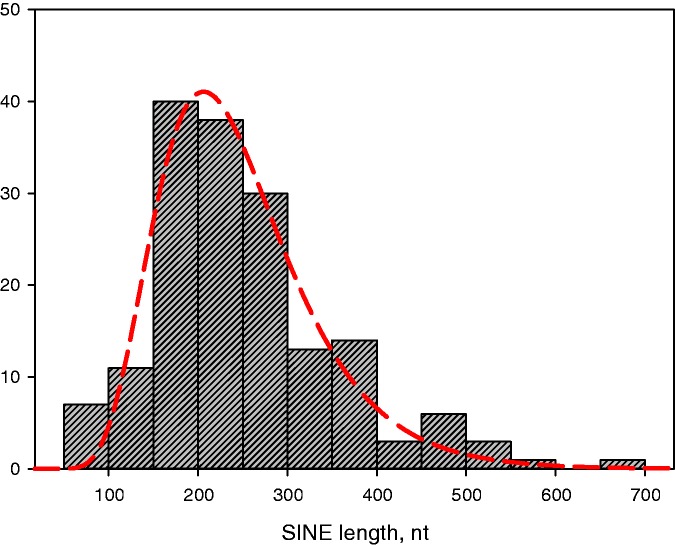

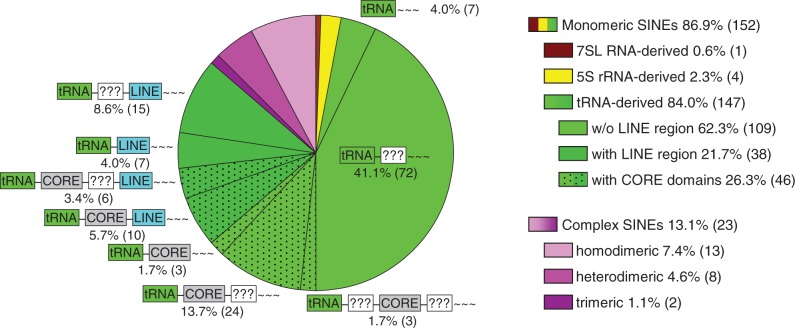

The length of SINE consensus sequences without tail ranges from 75 to 662 nt, with the mean length of 253 nt (Figure 1). In terms of structure (Figure 2), the majority of families are monomeric (87%) tRNA-derived (84%; green sectors in Figure 2) SINEs. There are roughly 3 times less SINE families with the LINE-derived region (dark green sectors) than without it (light green sectors), although this ratio can decrease as new partner LINEs become identified. More than a quarter families contain CORE and similar domains (dotted sectors). The most common SINE structure is a tRNA-derived head followed by a body of unknown origin and a tail (41%); other patterns range from 2 to 14%. Complex SINE families amount to 13% (purple sectors in Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Length distribution for 175 eukaryotic SINE families (without tail). The range is from 75 to 662 nt with the mean and median length of 253 and 236 nt, respectively.

Figure 2.

Occurrence of different SINE structures. Complex SINEs are highlighted by shades of purple; brown and yellow sectors represent 7SL RNA- and 5S rRNA-derived SINEs, respectively; tRNA-derived are shown in shades of green (dark and light hues correspond to SINEs with and without LINE-derived region, respectively). Dotted sectors indicate SINEs with CORE domains; schematic SINE structures (as in SINETable/Supplementary Table S1) are shown next to or over the corresponding sectors. Percentage is the fraction of a structure among 175 SINE families, and the number in parentheses is the number of SINE families representing the structure.

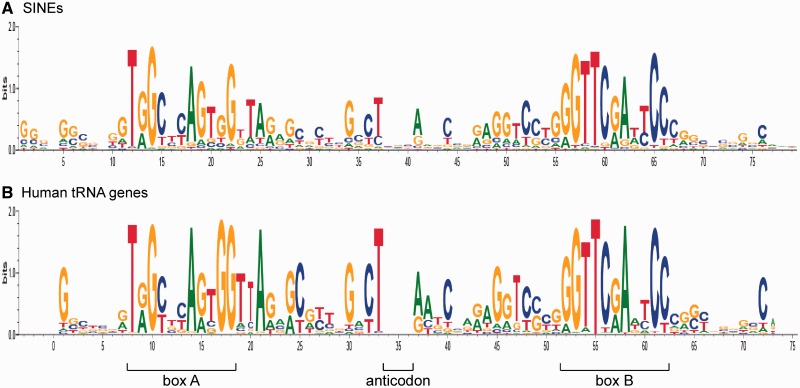

The collection of consensus sequences was further analysed in an attempt to identify similar patterns in their structure. All tRNA-derived sequences of SINE families were used to generate a sequence logo, which was compared with that of human tRNA genes (Figure 3; Supplementary Alignments S4). Overall, the same sequence pattern is observed in both cases, although it is less pronounced for SINEs (i.e. SINE sequences are more variable). SINEs have a short G-rich extra sequence at the 5′-end compared with tRNAs (and of course extra downstream sequences).

Figure 3.

Conservation of tRNA-derived sequences in SINEs. Sequence logos of (A) 175 tRNA-derived sequences in SINEs (including those in the second and third monomers of complex SINEs) and (B) 359 human tRNA genes (10) were generated by WebLogo 3.1 (13). The multiple alignments were edited to eliminate gaps in the logos. The original alignments of tRNAs and tRNA-derived sequences in SINEs are available in Supplementary Alignments S4.

Special surveys were carried out for the body region targeted at the central CORE-like domains and LINE-derived regions. This allowed us to identify such domains in certain SINEs, where they remained unnoticed (e.g. the CORE domain was found in several sea urchin SINEs), as well as to identify two new central domains named α and β. As a result, the new consensus sequences were generated for most central domains (CORE, Deu, V, Ceph, α and β) (Supplementary Alignments S2). A similar analysis of the body 3′ terminal regions allowed us to generate multiple alignments and consensus sequences for four LINE-derived regions corresponding to Bov-B, CR1 and two L2 LINEs (Supplementary Alignments S3).

Similar resources

The most comprehensive up-to-date database of repetitive genomic elements (REs) is RU (11). De facto, it has become the standard source for RE research and nomenclature. RU includes many other types of REs apart from SINEs, whereas SINE consensus sequences represent families and subfamilies from groups of organisms and individual genomes in the same pool. Clearly, SINEBase that covers only SINE families cannot be considered as a RU replacement. At the same time, our analysis revealed a number of discrepancies between SINEBase and RU, what we believe stem from certain errors and ambiguities in RU (Supplementary Table S2). (i) As many as 80 records annotated in RU as SINEs (527 by the analysis time) were not included in SINEBase as they correspond to other RE types (largely, LINEs); (ii) SINEBase assigns consistent names to the same SINEs in different species and to SINE subfamilies, which in RU can be assigned different names (only 130 RU records correspond to SINEBase families, whereas 258 correspond to subfamilies and species variants); (iii) A substantial fraction of SINEBase families (45 in total) are missing from RU; and (iv) Finally, SINEBase uses a straightforward SINE nomenclature, which in most cases relies on the previously described SINEs, whereas RU tends to rename them. As an example, the RU naming scheme (39) (which changed several times) includes 43 records starting from ‘SINE2-’ and a text with numerous SINE2-2_CQ, SINE2-2_NV and SINE2-2_SP is hard to read. We renamed such families by omitting the redundant ‘SINEx’. Supplementary Table S2 lists all RU records annotated as SINEs and describes their status in SINEBase.

Furthermore, the RepeatMasker program (http://www.repeatmasker.org) routinely used to identify SINEs relies on (slightly modified) RU records. RepeatMasker finds the best hit among RU sequences based on certain statistical parameters, such that a high similarity over short fragments can be considered more significant than a lower similarity throughout the element; this is particularly true for short sequences. At the same time, different SINE families can share the same (e.g. 5S rRNA-derived) module, and the sequences in this region can be highly similar, whereas those in the other regions are dissimilar. The situation is even worse for SINE subfamilies distinguished by diagnostic characters (often single nucleotide), as RepeatMasker considers them on par with random (non-diagnostic) mutations. Because many RU records belong to the same SINE family, the RepeatMasker can recognize a set of sequences of the same family as several different SINEs.

As a result, blind reliance on this tool often leads to confusing misidentifications of SINEs or even anecdotal errors in otherwise competent publications, e.g. hundreds thousands of Alu copies in the genomes of mouse and rat (rodents have a different much shorter B1 SINE; Alu is limited to primates) or a single 51-nt B2 in the human genome (SINEs are longer and repetitive; most likely it is a tRNA pseudogene) (12). We have designed the SINESearch tool to be free from these limitations.

SINEBase website

SINEBase is hosted on an Apache web server using CGI-Perl and JavaScript to generate dynamic HTML pages. It is fully functional with major web browsers. Some older browsers tested still allow the backbone functions of the site, whereas some decorations may not work (e.g. SINETable sorting). The database will be updated as new SINE data become available to us (at least biannually). We encourage the submission of new data on SINE families. SINEBase is freely available at http://sines.eimb.ru. There are no access restrictions for academic and commercial use. We kindly ask all users to cite this article if they use SINEBase in their publications.

CONCLUSION

As more and more genome sequences become available, the number of known SINEs will grow and new researchers will be involved in their analysis. SINEBase is aimed to bring some order to the system of SINEs and to set a basis for further studies on these genomic elements. The database of SINE consensus sequences and motifs will be updated as new SINEs are described. We will develop new tools to assist in SINE analysis (the identification of TSDs and internal duplications are first in the list). We appreciate feedback from SINEBase users to improve the service.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Caption 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Sequence 1, Supplementary Alignments 1–4 and Supplementary References [13–99].

FUNDING

Molecular and Cellular Biology Program of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Russian Foundation for Basic Research [project nos. 13-04-01678-а and 11-04-00439-a]. Funding for open access charge: Personal funds.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to Dr. Youri Kravatsky for his expert advice on web programming. All SINE elements originally published in Repbase have been reproduced with permission from the Genetic Information Research Institute, which reserves all rights in the material. We thank Drs. J. Jurka and V. V. Kapitonov for allowing access to their data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Makalowski W. Genomic scrap yard: how genomes utilize all that junk. Gene. 2000;259:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belancio VP, Hedges DJ, Deininger P. Mammalian non-LTR retrotransposons: for better or worse, in sickness and in health. Genome Res. 2008;18:343–358. doi: 10.1101/gr.5558208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okada N, Sasaki T, Shimogori T, Nishihara H. Emergence of mammals by emergency: exaptation. Genes Cells. 2010;15:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramerov DA, Vassetzky NS. SINEs. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. RNA. 2011;2:772–786. doi: 10.1002/wrna.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Mammalian retroelements. Genome Res. 2002;12:1455–1465. doi: 10.1101/gr.282402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gogvadze E, Buzdin A. Retroelements and their impact on genome evolution and functioning. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:3727–3742. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada N, Hamada M, Ogiwara I, Ohshima K. SINEs and LINEs share common 3' sequences: a review. Gene. 1997;205:229–243. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohshima K, Okada N. SINEs and LINEs: symbionts of eukaryotic genomes with a common tail. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005;110:475–490. doi: 10.1159/000084981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramerov DA, Vassetzky NS. Origin and evolution of SINEs in eukaryotic genomes. Heredity. 2011;107:487–495. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juhling F, Morl M, Hartmann RK, Sprinzl M, Stadler PF, Putz J. tRNAdb 2009: compilation of tRNA sequences and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D159–D162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naked Mole Rat Genome Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat. Nature. 2011;479:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piskurek O, Nishihara H, Okada N. The evolution of two partner LINE/SINE families and a full-length chromodomain-containing Ty3/Gypsy LTR element in the first reptilian genome of Anolis carolinensis. Gene. 2009;441:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogiwara I, Miya M, Ohshima K, Okada N. V-SINEs: a new superfamily of vertebrate SINEs that are widespread in vertebrate genomes and retain a strongly conserved segment within each repetitive unit. Genome Res. 2002;12:316–324. doi: 10.1101/gr.212302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi K, Terai Y, Nishida M, Okada N. A novel family of short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs) from cichlids: the patterns of insertion of SINEs at orthologous loci support the proposed monophyly of four major groups of cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:391–407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao F, Qi J, Schuster SC. Tracking the past: interspersed repeats in an extinct Afrotherian mammal, Mammuthus primigenius. Genome Res. 2009;19:1384–1392. doi: 10.1101/gr.091363.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikaido M, Nishihara H, Hukumoto Y, Okada N. Ancient SINEs from African Endemic Mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:522–527. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deininger PL, Jolly DJ, Rubin CM, Friedmann T, Schmid CW. Base sequence studies of 300 nucleotide renatured repeated human DNA clones. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;151:17–33. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasui Y, Nasuda S, Matsuoka Y, Kawahara T. The Au family, a novel short interspersed element (SINE) from Aegilops umbellulata. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001;102:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett JA, Kawahara T, Watanabe H, Yasui Y. A SINE family widely distributed in the plant kingdom and its evolutionary history. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;61:505–514. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-0026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kido Y, Himberg M, Takasaki N, Okada N. Amplification of distinct subfamilies of short interspersed elements during evolution of the Salmonidae. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;241:633–644. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matveev V, Okada N. Retroposons of salmonoid fishes (Actinopterygii: Salmonoidei) and their evolution. Gene. 2009;434:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krayev AS, Kramerov DA, Skryabin KG, Ryskov AP, Bayev AA, Georgiev GP. The nucleotide sequence of the ubiquitous repetitive DNA sequence B1 complementary to the most abundant class of mouse fold-back RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:1201–1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.6.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veniaminova NA, Vassetzky NS, Kramerov DA. B1 SINEs in different rodent families. Genomics. 2007;89:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramerov DA, Vassetzky NS. Structure and origin of a novel dimeric retroposon B1-dID. J. Mol. Evol. 2001;52:137–143. doi: 10.1007/s002390010142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krayev AS, Markusheva TV, Kramerov DA, Ryskov AP, Skryabin KG, Bayev AA, Georgiev GP. Ubiquitous transposon-like repeats B1 and B2 of the mouse genome: B2 sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7461–7475. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.23.7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee IY, Westaway D, Smit AF, Wang K, Seto J, Chen L, Acharya C, Ankener M, Baskin D, Cooper C, et al. Complete genomic sequence and analysis of the prion protein gene region from three mammalian species. Genome Res. 1998;8:1022–1037. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.10.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishihara H, Smit AF, Okada N. Functional noncoding sequences derived from SINEs in the mammalian genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:864–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.5255506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams DS, Eickbush TH, Herrera RJ, Lizardi PM. A highly reiterated family of transcribed oligo(A)-terminated, interspersed DNA elements in the genome of Bombyx mori. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;187:465–478. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90327-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, Liu T, Li D, Zhang Z, Xia Q, Zhou Z. BmSE, a SINE family with 3' ends of (ATTT) repeats in domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori) J. Genet. Genomics. 2010;37:125–135. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60031-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenstra JA, van Boxtel JA, Zwaagstra KA, Schwerin M. Short interspersed nuclear element (SINE) sequences of the Bovidae. Anim. Genet. 1993;24:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1993.tb00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng JF, Printz R, Callaghan T, Shuey D, Hardison RC. The rabbit C family of short, interspersed repeats. Nucleotide sequence determination and transcriptional analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;176:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krane DE, Clark AG, Cheng JF, Hardison RC. Subfamily relationships and clustering of rabbit C repeats. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1991;8:1–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavrent'eva MV, Rivkin MI, Shilov AG, Kobets ML, Rogozin IB, Serov OL. B2-like repetitive sequence in the genome of the American mink. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR. 1989;307:226–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassetzky NS, Kramerov DA. CAN–a pan-carnivore SINE family. Mamm. Genome. 2002;13:50–57. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-2111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimamura M, Abe H, Nikaido M, Ohshima K, Okada N. Genealogy of families of SINEs in cetaceans and artiodactyls: the presence of a huge superfamily of tRNA(Glu)-derived families of SINEs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1046–1060. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikaido M, Matsuno F, Abe H, Shimamura M, Hamilton H, Matsubayashi H, Okada N. Evolution of CHR-2 SINEs in cetartiodactyl genomes: possible evidence for the monophyletic origin of toothed whales. Mamm. Genome. 2001;12:909–915. doi: 10.1007/s0033501-1015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. A universal classification of eukaryotic transposable elements implemented in Repbase. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:411–412. doi: 10.1038/nrg2165-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmen MW, Bird A. Sequence analysis of transposable elements in the sea squirt, Ciona intestinalis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:1685–1694. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endoh H, Nagahashi S, Okada N. A highly repetitive and transcribable sequence in the tortoise genome is probably a retroposon. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;189:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasaki T, Takahashi K, Nikaido M, Miura S, Yasukawa Y, Okada N. First application of the SINE (short interspersed repetitive element) method to infer phylogenetic relationships in reptiles: an example from the turtle superfamily Testudinoidea. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:705–715. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piskurek O, Nikaido M, Boeadi, Baba M, Okada N. Unique mammalian tRNA-derived repetitive elements in dermopterans: the t-SINE family and its retrotransposition through multiple sources. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1659–1668. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitz J, Zischler H. A novel family of tRNA-derived SINEs in the colugo and two new retrotransposable markers separating dermopterans from primates. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;28:341–349. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izsvak Z, Ivics Z, Garcia-Estefania D, Fahrenkrug SC, Hackett PB. DANA elements: a family of composite, tRNA-derived short interspersed DNA elements associated with mutational activities in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1077–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borodulina OR, Kramerov DA. PCR-based approach to SINE isolation: simple and complex SINEs. Gene. 2005;349:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Churakov G, Smit AF, Brosius J, Schmitz J. A novel abundant family of retroposed elements (DAS-SINEs) in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:886–893. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serdobova IM, Kramerov DA. Short retroposons of the B2 superfamily: evolution and application for the study of rodent phylogeny. J. Mol. Evol. 1998;46:202–214. doi: 10.1007/pl00006295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakagami M, Ohshima K, Mukoyama H, Yasue H, Okada N. A novel tRNA species as an origin of short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs). Equine SINEs may have originated from tRNA(Ser) J. Mol. Biol. 1994;239:731–735. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borodulina OR, Kramerov DA. Short interspersed elements (SINEs) from insectivores. Two classes of mammalian SINEs distinguished by A-rich tail structure. Mamm. Genome. 2001;12:779–786. doi: 10.1007/s003350020029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tu Z. Genomic and evolutionary analysis of Feilai, a diverse family of highly reiterated SINEs in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:760–772. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tu Z, Li S, Mao C. The changing tails of a novel short interspersed element in Aedes aegypti: genomic evidence for slippage retrotransposition and the relationship between 3′ tandem repeats and the poly(dA) tail. Genetics. 2004;168:2037–2047. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ogiwara I, Miya M, Ohshima K, Okada N. Retropositional parasitism of SINEs on LINEs: identification of SINEs and LINEs in elasmobranchs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1238–1250. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kido Y, Aono M, Yamaki T, Matsumoto K, Murata S, Saneyoshi M, Okada N. Shaping and reshaping of salmonid genomes by amplification of tRNA-derived retroposons during evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:2326–2330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milner RJ, Bloom FE, Lai C, Lerner RA, Sutcliffe JG. Brain-specific genes have identifier sequences in their introns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:713–717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akasaki T, Nikaido M, Nishihara H, Tsuchiya K, Segawa S, Okada N. Characterization of a novel SINE superfamily from invertebrates: "Ceph-SINEs" from the genomes of squids and cuttlefish. Gene. 2010;454:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gogolevsky KP, Kramerov DA. Short interspersed elements (SINEs) of the Geomyoidea superfamily rodents. Gene. 2006;373:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Churakov G, Sadasivuni MK, Rosenbloom KR, Huchon D, Brosius J, Schmitz J. Rodent evolution: back to the root. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:1315–1326. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bejerano G, Lowe CB, Ahituv N, King B, Siepel A, Salama SR, Rubin EM, Kent WJ, Haussler D. A distal enhancer and an ultraconserved exon are derived from a novel retroposon. Nature. 2006;441:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nature04696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bradfield JY, Locke J, Wyatt GR. An ubiquitous interspersed DNA sequence family in an insect. DNA. 1985;4:357–363. doi: 10.1089/dna.1985.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Munemasa M, Nikaido M, Nishihara H, Donnellan S, Austin CC, Okada N. Newly discovered young CORE-SINEs in marsupial genomes. Gene. 2008;407:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warren WC, Hillier LW, Marshall Graves JA, Birney E, Ponting CP, Grutzner F, Belov K, Miller W, Clarke L, Chinwalla AT, et al. Genome analysis of the platypus reveals unique signatures of evolution. Nature. 2008;453:175–183. doi: 10.1038/nature06936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilbert N, Labuda D. Evolutionary inventions and continuity of CORE-SINEs in mammals. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:365–377. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gentles AJ, Wakefield MJ, Kohany O, Gu W, Batzer MA, Pollock DD, Jurka J. Evolutionary dynamics of transposable elements in the short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica. Genome Res. 2007;17:992–1004. doi: 10.1101/gr.6070707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gogolevsky KP, Vassetzky NS, Kramerov DA. 5S rRNA-derived and tRNA-derived SINEs in fruit bats. Genomics. 2009;93:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishihara H, Kuno S, Nikaido M, Okada N. MyrSINEs: a novel SINE family in the anteater genomes. Gene. 2007;400:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohshima K, Okada N. Generality of the tRNA origin of short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs). Characterization of three different tRNA-derived retroposons in the octopus. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;243:25–37. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsuchimoto S, Hirao Y, Ohtsubo E, Ohtsubo H. New SINE families from rice, OsSN, with poly(A) at the 3' ends. Genes Genet. Syst. 2008;83:227–236. doi: 10.1266/ggs.83.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gogolevsky KP, Vassetzky NS, Kramerov DA. Bov-B-mobilized SINEs in vertebrate genomes. Gene. 2008;407:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singer DS, Parent LJ, Ehrlich R. Identification and DNA sequence of an interspersed repetitive DNA element in the genome of the miniature swine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2780. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.6.2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mochizuki K, Umeda M, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E. Characterization of a plant SINE, p-SINE1, in rice genomes. Jpn. J. Genet. 1992;67:155–166. doi: 10.1266/jjg.67.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Motohashi R, Mochizuki K, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E. Structures and distribution of p-SINE1 members in rice genomes. Theoretical Appl. Genet. 1997;95:359–368. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sunter JD, Patel SP, Skilton RA, Githaka N, Knowles DP, Scoles GA, Nene V, de Villiers E, Bishop RP. A novel SINE family occurs frequently in both genomic DNA and transcribed sequences in ixodid ticks of the arthropod sub-phylum Chelicerata. Gene. 2008;415:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piskurek O, Austin CC, Okada N. Sauria SINEs: Novel short interspersed retroposable elements that are widespread in reptile genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 2006;62:630–644. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kosushkin SA, Borodulina OR, Grechko VV, Kramerov DA. A new family of interspersed repeats from squamate reptiles. Mol. Biol. (Mosk) 2006;40:378–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deragon JM, Landry BS, Pelissier T, Tutois S, Tourmente S, Picard G. An analysis of retroposition in plants based on a family of SINEs from Brassica napus. J. Mol. Evol. 1994;39:378–386. doi: 10.1007/BF00160270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deragon JM, Zhang X. Short interspersed elements (SINEs) in plants: origin, classification, and use as phylogenetic markers. Syst. Biol. 2006;55:949–956. doi: 10.1080/10635150601047843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lenoir A, Lavie L, Prieto JL, Goubely C, Cote JC, Pelissier T, Deragon JM. The evolutionary origin and genomic organization of SINEs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:2315–2322. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Myouga F, Tsuchimoto S, Noma K, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E. Identification and structural analysis of SINE elements in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Genes Genet. Syst. 2001;76:169–179. doi: 10.1266/ggs.76.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Daniels GR, Deininger PL. A second major class of Alu family repeated DNA sequences in a primate genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:7595–7610. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.21.7595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roos C, Schmitz J, Zischler H. Primate jumping genes elucidate strepsirrhine phylogeny. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10650–10654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403852101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Daniels GR, Deininger PL. Characterization of a third major SINE family of repetitive sequences in the galago genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1649–1656. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holt RA, Subramanian GM, Halpern A, Sutton GG, Charlab R, Nusskern DR, Wincker P, Clark AG, Ribeiro JM, Wides R, et al. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:129–149. doi: 10.1126/science.1076181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. A novel class of SINE elements derived from 5S rRNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:694–702. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ohshima K, Koishi R, Matsuo M, Okada N. Several short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs) in distant species may have originated from a common ancestral retrovirus: characterization of a squid SINE and a possible mechanism for generation of tRNA-derived retroposons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6260–6264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matveev V, Nishihara H, Okada N. Novel SINE families from salmons validate Parahucho (Salmonidae) as a distinct genus and give evidence that SINEs can incorporate LINE-related 3'-tails of other SINEs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1656–1666. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spotila LD, Hirai H, Rekosh DM, Lo Verde PT. A retroposon-like short repetitive DNA element in the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni. Chromosoma. 1989;97:421–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00295025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nisson PE, Hickey RJ, Boshar MF, Crain WR., Jr Identification of a repeated sequence in the genome of the sea urchin which is transcribed by RNA polymerase III and contains the features of a retroposon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1431–1452. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.4.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carpenter CD, Bruskin AM, Spain LM, Eldon ED, Klein WH. The 3' untranslated regions of two related mRNAs contain an element highly repeated in the sea urchin genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7829–7842. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.23.7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grechko VV, Kosushkin SA, Borodulina OR, Butaeva FG, Darevsky IS. Short interspersed elements (SINEs) of squamate reptiles (Squam1 and Squam2): structure and phylogenetic significance. J. Exp. Zool. 2011;316B:212–226. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Luchetti A, Mantovani B. Talua SINE biology in the genome of the Reticulitermes subterranean termites (Isoptera, Rhinotermitidae) J. Mol. Evol. 2009;69:589–600. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Luchetti A, Mantovani B. Molecular characterization, genomic distribution and evolutionary dynamics of Short INterspersed Elements in the termite genome. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2011;285:175–184. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smit AF, Riggs AD. MIRs are classic, tRNA-derived SINEs that amplified before the mammalian radiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:98–102. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yoshioka Y, Matsumoto S, Kojima S, Ohshima K, Okada N, Machida Y. Molecular characterization of a short interspersed repetitive element from tobacco that exhibits sequence homology to specific tRNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6562–6566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nishihara H, Terai Y, Okada N. Characterization of Novel Alu- and tRNA-Related SINEs from the Tree Shrew and Evolutionary Implications of Their Origins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:1964–1972. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Feschotte C, Fourrier N, Desmons I, Mouches C. Birth of a retroposon: the Twin SINE family from the vector mosquito Culex pipiens may have originated from a dimeric tRNA precursor. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:74–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kajikawa M, Okada N. LINEs mobilize SINEs in the eel through a shared 3' sequence. Cell. 2002;111:433–444. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Borodulina OR, Kramerov DA. Wide distribution of short interspersed elements among eukaryotic genomes. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin Z, Nomura O, Hayashi T, Wada Y, Yasue H. Characterization of a SINE species from vicuna and its distribution in animal species including the family Camelidae. Mamm. Genome. 2001;12:305–308. doi: 10.1007/s003350010272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]