Abstract

The sulfonamide antibiotics inhibit dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), a key enzyme in the folate pathway of bacteria and primitive eukaryotes. However, resistance mutations have severely compromised the usefulness of these drugs. Here, we report structural, computational and mutagenesis studies on the catalytic and resistance mechanisms of DHPS. By performing the enzyme-catalyzed reaction in crystalline DHPS, we have structurally characterized key intermediates along the reaction pathway. Results support an SN1 reaction mechanism via formation of a novel cationic pterin intermediate. We also show that two conserved loops generate a substructure during catalysis that creates a specific binding pocket for p-aminobenzoic acid, one of the two DHPS substrates. This substructure, together with the pterin-binding pocket, explains the roles of the conserved active site residues, and reveals how sulfonamide resistance arises.

Drug resistance has led to a decrease in the clinical utility of virtually all marketed antibacterial agents (1), and the sulfonamide class of antibiotics (sulfa drugs) was an early victim of this phenomenon (2, 3). Sulfa drugs interrupt the essential folate pathway in bacteria and primitive eukaryotes, and target the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) which catalyzes the condensation of 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8–dihydropterin-pyrophosphate (DHPP) with p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) in the production of the folate intermediate, 7,8-dihydropteroate (4). Sulfa drugs target both gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infections, and combination therapies such as co-trimoxazole, a mixture of the sulfa drug sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitor trimethoprim, are effective against many pathogenic microorganisms (5). However, DHPS mutations have been frequently characterized in many clinical isolates, relegating sulfonamide-based therapies to second or third line options.

Co-trimoxazole has proven to be effective against several emerging threats including community acquired multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (6, 7) and Pneumocystis jiroveci infections in immune-compromised patients (8). DHPS therefore remains an important drug target, and we are developing new inhibitors that target the DHPP-binding pocket of the enzyme (9–11). Understanding the DHPS catalytic mechanism and the mechanistic basis of sulfa drug resistance is crucial for these drug discovery efforts. DHPS has a TIM barrel α/β structure, and many of the drug resistance point mutations are located within two flexible and conserved loops that appear to make important contributions to the active site (9, 11–15). The inability to observe these loops in their catalytic and/or substrate-bound conformations in the available crystal structures has hampered efforts to understand the structural basis of catalysis and sulfa drug resistance.

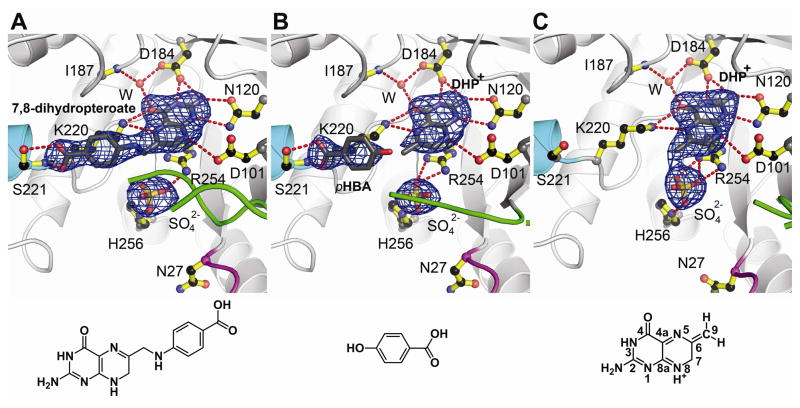

DHPS catalyzes the formation of a bond between the amino nitrogen of pABA and the C9 carbon of DHPP with the elimination of pyrophosphate. It has been suggested that the reaction proceeds by an SN2-like mechanism (14), but the NH2 group of pABA is a poor nucleophile and crystal structures of DHPS with the substrate analog 6-hydroxymethyl-pterin-pyrophosphate (PtPP) and the product analog pteroate suggest that the required attack geometry is sterically disfavored (9). To visualize DHPP and pABA in the active site, both compounds were soaked into our Bacillus anthracis DHPS (BaDHPS) crystals (table S1) (16). Both molecules in the asymmetric unit (molecules ‘A’ and ‘B’) were found to have performed catalysis leaving the product 7,8-dihydropteroate bound at the active site (Fig. 1A). This was unexpected because these crystals are grown at pH 9.0 and in 1.4 M sulfate, conditions that would be expected to hinder catalysis. The co-structure closely resembles the pteroate co-structure (9), and both have a sulfate ion instead of the eliminated pyrophosphate of DHPP in the anion-binding pocket. A new feature is the partial ordering of loop2 in molecule A that packs onto the pABA moiety which is now sandwiched between loop2 and Lys220. This is the first indication that one role of loop2 is to stabilize the binding of pABA at the active site.

Fig. 1.

Products generated by crystalline BaDHPS. A. The product 7,8-dihydropteroate after soaking crystals in DHPP, pABA and Mg2+. B. DHP+ and pHBA after soaking crystals in DHPP, pHBA and Mg2+. C. DHP+ after soaking crystals in DHPP and Mg2+. In each figure, loop1 is shown in magenta, loop2 is shown in green, the N-terminus of helix αLoop7 is shown in teal, and a sulfate ion occupies the anion binding pocket. The Fo-Fc electron densities were generated from refined structures in which the indicated ligands were omitted, and are contoured at 3σ. Below each figure is the structure of the key molecule bound in the complex. DHP+ is bound in both B and C, but the structure is only shown in C with the pterin ring atoms numbered.

To investigate whether pABA is locked into place before product formation, we replaced pABA with p-hydroxybenzoic acid (pHBA), a less-reactive pABA analog (16). The structure (table S1) showed that pHBA indeed binds in the same location as pABA with a partially ordered loop2 clamping it in place (Fig. 1B). The structure also revealed that DHPP had lost its pyrophosphate group in both molecules A and B leaving the dihydropterin core in the pterin-binding pocket. There is no evidence of an OH group at C9 which would result from hydrolysis of an unstable carbocation. This structure confirms that the pyrophosphate is not removed by an SN2 nucleophilic attack but is eliminated in a manner consistent with an SN1 reaction.

We explored alternatives to an SN2 mechanism by performing quantum chemical modelling of the initial step of a “pure” SN1 reaction: the cleavage of the C9—O bond of DHPP in the absence of pABA (figs. S1 and S2) (16). Three key results resulted from these computational analyses; first, the barrier to bond breaking is only ~24 kcal mol−1; second, the essential Mg2+ ion (17) adds the leaving pyrophosphate α-oxygen to its coordination shell, thereby acting as a Lewis acid and assisting pyrophosphate elimination; third, the carbocation formed at the C9 position is stabilized by charge delocalization into the pterin ring. This predicted scenario is analogous to the SN1 mechanism of the prenyltransferases (18, 19). Natural bond order analyses (20) before and after bond-breaking indicate resonance stabilization of the carbocation that includes a partial iminium character of N8. We propose that this cationic intermediate, which we shall refer to as DHP+, is the dihydropterin core species that we observe in the crystal structure.

The calculations suggest that DHPS can slowly release pyrophosphate from DHPP independent of pABA binding at the active site. To test this, we soaked BaDHPS crystals in DHPP without pABA (16), and the structure (table S1) revealed that pyrophosphate had indeed been released from DHPP (Fig. 1C). Loop2 was completely disordered which supports its role in helping to lock pABA onto the surface of Lys220. The calculations also support the essential role of the Mg2+ ion (17) and we confirmed this experimentally for BaDHPS (fig. S3A) (16). To visualize the effect of removing Mg2+, we pre-soaked crystals in EDTA to remove Mg2+, and then added EDTA and DHPP for a further three hours soaking (16). The resulting structure (table S1) showed that pyrophosphate is still cleaved from DHPP but remains trapped in the anion-binding pocket where it appears to stabilize the conformations of loop1 and loop2 (fig. S4). Therefore, Mg2+ is not absolutely required for the cleavage of pyrophosphate from DHPP but may play a key role in its release from the enzyme.

We have also completed two crystal structures of Yersinia pestis DHPS (YpDHPS) (16): the apo structure (fig. S5A, table S2) and the complex with pteroate (fig. S5B, table S2). Although both structures closely resemble those of BaDHPS (9), two features particularly recommend them for mechanistic studies: loop1 and loop2 are both unconstrained by crystal contacts in the apo structure and free to adopt functional conformations; and the crystals are grown in more physiological conditions, pH 6 – 7 and 12% PEG 20,000.

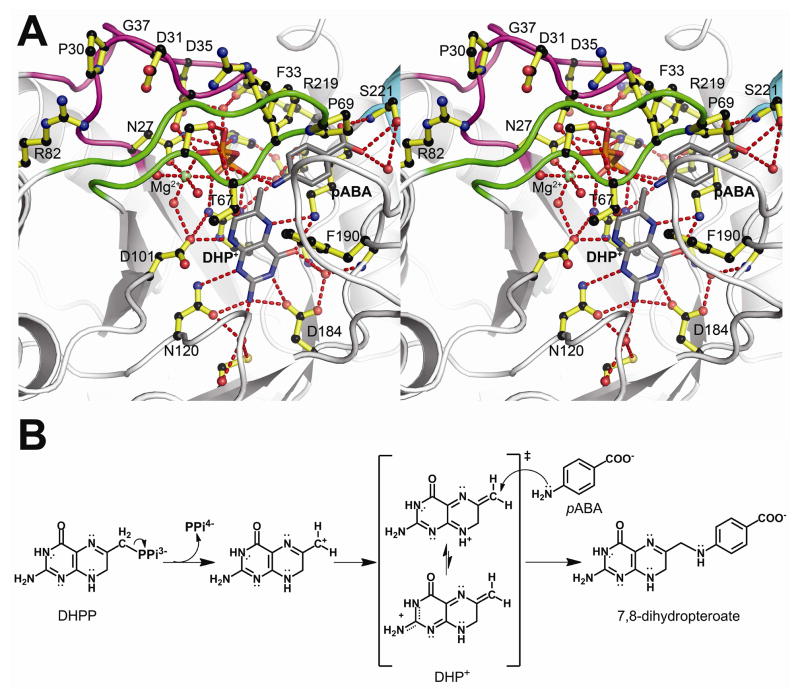

Soaking DHPP and pABA into YpDHPS crystals gave a structure (table S2) that apparently shows the enzyme near the transition state (Fig. 2A, fig. S6A and movie S1). In both molecules in the asymmetric unit, pABA, DHP+, pyrophosphate, and a Mg2+ ion are all present within a highly organized loop1 and loop2 substructure prior to product formation. The released pyrophosphate occupies a pocket comprising residues Ser32, Ser34 and Asp35 from loop1 (the latter two residues via an ordered water molecule), Ser66 and Thr67 from loop2, and Arg254 and His256 from the anion binding site (we use BaDHPS numbering and the sequence alignment is shown in fig. S7). The Mg2+ ion is octahedrally coordinated with the two distal oxygen atoms of the pyrophosphate, the Oδ1 oxygen of Asn27 and three water molecules. The entire active site is covered by the distal end of loop1 encompassing Pro30 to Gly37 that forms a β-ribbon structure. The component residues make a number of stabilizing interactions; Asp31 is clamped between Arg68 and Arg82, Ser32 interacts with the pyrophosphate as noted above, Ser34 interacts with Arg219 and Asp35 interacts with Asn27.

Fig. 2.

The DHPS catalytic mechanism. A. Stereoview of the Y. pestis (Yp) DHPS ordered active site generated from YpDHPS crystals soaked in DHPP, pABA and Mg2+. Loop1 (magenta), loop2 (green) and an octahedrally coordinated Mg2+ ion (green ball) are all organized by the pyrophosphate (orange/red), and a pABA molecule is bound within a specific binding pocket. Note that loop1 caps the active site via a distal β-ribbon substructure, and the distal Pro69 of loop2 engages the bound pABA. The residue numbering corresponds to BaDHPS. B. The proposed SN1 chemical reaction catalyzed by DHPS. Pyrophosphate is first removed from DHPP. The resulting cationic intermediate species can adopt the DHP+ resonance forms shown in the square brackets in which the positive charge is delocalized into the pterin rings and stabilized by the pterin-binding pocket. The amine group of pABA finally attacks DHP+ at the C9 carbon atom to generate the product, 7,8-dihydropteroate.

The YpDHPS complex structure (Fig. 2A) explains three key features of the catalytic mechanism and the active site. First, it explains that an essential role of Mg2+ is to order the loop1/loop2 substructure, as well as to stabilize the leaving pyrophosphate. The conformations and locations of the active site residues, the bound substrates and the Mg2+ ion closely match those of the computed state in which the C—O bond has been broken (fig. S2D, RMSD 0.77 Å) (16). Second, it explains why the residues within the two loops are so highly conserved. Finally, it explains why the pABA-binding site has been so difficult to visualize - it is only fully formed in this complex. Phe33 from loop1, Pro69 from loop2, Lys220 and Phe189 are all highly conserved, and combine to form the pABA-binding pocket. Also, loop1 forms a protective lid over the active site with a restricted entrance that matches the shape and chemistry of pABA. Consistent with our previous results (9), the carboxylate moiety of pABA is accommodated by Ser221 and the helix dipole of helix αLoop7.

Our data show that the role of the pterin-binding pocket is to first bind DHPP and then promote the release of pyrophosphate by stabilizing a carbocation on the C9 carbon. The likely roles of the conserved Asp184 and Asp101 are to stabilize resonance forms that move the positive charge away from this primary carbocation and toward the N3/2-amino and N8 nitrogen atoms, respectively, either by ionic interactions or by proton abstraction (16). The electrophilic DHP+ intermediate can then react with the incoming pABA nitrogen via nucleophilic conjugate addition. We showed experimentally (16) that the release of pyrophosphate, and presumably the dissolution of the intermediate state substructure, is promoted by pABA (fig. S3B). The SN1 mechanism that we propose is shown in Fig. 2B.

We prepared eight active site BaDHPS mutants to test this proposal (16). The kinetic parameters were measured using an assay that monitors pyrophosphate release (16), and the results are summarized in Table 1. Parallel assays were performed in the presence of high (200 μM) pABA and high (50 μM) DHPP to allow independent measurements of the binding affinities of the two substrates. In general, the mutations support the proposed mechanism and the intermediate state substructure shown in Fig. 2A. Loop1 mutations N27A, F33A, F33L and D35A, and loop2 mutation S66A, all primarily affect the binding of pABA and have little effect on the binding of DHPP. Each of these residues, directly or indirectly, contributes to the pABA-binding site. The pterin-pocket mutants, D101N and D184N, were designed to investigate the effect of removing these negative charges. D184N is unable to bind DHPP because the asparagine side chain adopts a rotamer that prevents its interaction with the pterin ring (table S1 and fig. S8). However, D101N shows efficient binding to both DHPP and pABA but has a much reduced kobs. Finally, K220Q shows reduced binding to pABA and DHPP, consistent with the role of Lys220 in binding both substrates.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of wild-type and mutant BaDHPS

| Enzyme | DHPP

|

pABA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kobs(s−1) | Km(μM) | kobs(s−1) | Km(μM) | |

| WT | 0.545 ± 0.0068 | 3.16 ± 0.150 | 0.520 ± 0.0136 | 1.78 ± 0.218 |

| N27A | 0.007 ± 0.0001 | 5.82 ± 0.237 | ND | |

| F33A | 0.239 ± 0.0032 | 3.94 ± 0.192 | 0.789 ± 0.0327 | 507.90 ± 33.070 |

| F33L | 0.318 ± 0.0041 | 4.83 ± 0.210 | 0.563 ± 0.0086 | 185.90 ± 6.422 |

| D35A | 1.100 ± 0.0156 | 4.24 ± 0.210 | 0.999 ± 0.0117 | 71.21 ± 2.956 |

| S66A | 0.443 ± 0.0086 | 2.76 ± 0.215 | 0.459 ± 0.0088 | 14.45 ± 0.767 |

| D101N | 0.087 ± 0.0021 | 1.63 ± 0.192 | 0.086 ± 0.0010 | 3.57 ± 0.141 |

| D184N | ND* | ND | ||

| K220Q | 0.086 ± 0.0023 | 35.47 ± 1.735 | 0.177 ± 0.0111 | 410.20 ± 42.480 |

Too low activity

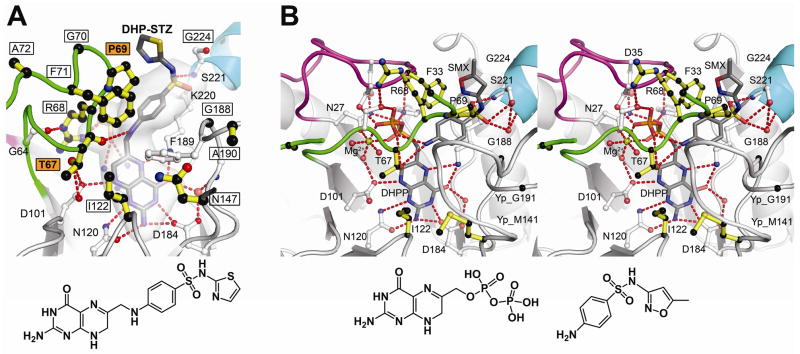

To investigate the mechanism of the sulfa drugs, we soaked BaDHPS crystals in DHPP and sulfathiazole (STZ) and determined the structure (table S1) (16). Molecule A revealed a clear DHP-STZ product (Fig. 3A) similar to that of the normal product (Fig. 1A) whereas molecule B revealed the bound drug before complex formation, similar to the pHBA complex (Fig. 1B). This supports previous studies which showed that sulfa drugs can replace pABA as DHPS substrates (21, 22). We then soaked DHPP and SMX into YpDHPS crystals and obtained a structure (table S2, Fig. 3B, fig. S6B and movie S2) similar to that observed with DHPP and pABA (Fig. 2A) (16). In molecules A and B, DHPP is bound, and loop1 and loop2 are ordered by pyrophosphate and an octahedrally coordinated Mg2+ion, but only molecule B contains SMX in the pABA-binding pocket. A difference from the YpDHPS pABA/DHPP structure (Fig. 2A) is that pyrophosphate remains attached to DHPP, but this has little effect on the loop conformations because both the location and Mg2+ coordination of the pyrophosphate are unaffected.

Fig. 3.

Sulfa drug mechanism and resistance. A. B. anthracis (Ba) DHPS crystals soaked in DHPP and sulfathiazole (STZ) reveal a covalent DHP-STZ adduct bound at the active site and stabilized by an ordered loop2. The boxed labeled residues are sites of sulfa drug resistance, and two major sites are labeled in boxed orange. The molecular envelope (light grey) encompasses the pterin- pABA- and anion-binding pockets. Note that the thiazole ring of STZ extends outside this pocket directly adjacent to Pro69. The structure of DHP-STZ is shown below the figure. B. Stereoview of the Y. pestis (Yp) DHPS active site occupied by DHPP, sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and an octahedrally coordinated Mg2+ ion. The structure is very similar to that shown in Fig. 2A that contains pABA in place of SMX. One difference from the pABA structure is that DHPP is intact with the pyrophosphate covalently attached. The residue numbering corresponds to BaDHPS. The structures of DHPP and SMX are shown below the figure. In both figures, loop1 is shown in magenta, loop2 is shown in green, and the N-terminus of helix α Loop7 is shown in teal.

The YpDHPS sulfa drug complex reveals the drug binding site. SMX perfectly fits the pABA-binding pocket with the negatively-charged oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group matching the pABA carboxyl group and their common phenyl groups engaging the same hydrophobic pocket in the loop1/loop2 substructure. Fig. 3B shows that the common sites of resistance are all clustered around this substructure. Phe33, Thr67 and Pro69 are frequently observed sites of resistance mutations (14) and form key elements of the pABA binding site. It has been observed that resistance is typically associated with regions of a drug that extend beyond the substrate envelope (23). Fig. 3A reveals that the thiazole and methoxazole rings of STZ and SMX, which have no counterparts in pABA, are positioned outside the DHPS substrate envelope and located such that mutations at Phe33 and Pro69 can significantly impede sulfa drug binding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca DuBois, Charles Pemble, Stefan Gajewski and Darcie Miller for assistance with the YpDHPS structure determination; John Bollinger and Eric Enemark for technical assistance; Dalia Hammoudeh and Charles Rock for helpful discussions; and staff at SERCAT for assistance with synchrotron data collection. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI070721 (S.W.W and R.E.L.), Cancer Center (CORE) Support Grant CA21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Data were collected at Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID and 22-BM beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Supporting institutions may be found at www.ser-cat.org/members.html. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. Coordinates and structure factors for all the structures described have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, and the PDB accession codes are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Footnotes

Materials and Methods

References

References and Notes

- 1.Rice LB. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:476. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sköld O. Drug Resist Updat. 2000;3:155. doi: 10.1054/drup.2000.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huovinen P. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1608. doi: 10.1086/320532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand N. Burg’s Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. 1996;2:527. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masters PA, O’Bryan TA, Zurlo J, Miller DQ, Joshi N. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:402. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyun DY, Mason EO, Forbes A, Kaplan SL. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:57. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181826e5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappas G, Athanasoulia AP, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME. J Chemother. 2009;21:115. doi: 10.1179/joc.2009.21.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merali S, Zhang Y, Sloan D, Meshnick S. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1075. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babaoglu K, Qi J, Lee RE, White SW. Structure. 2004;12:1705. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hevener KE, et al. J Med Chem. 2010;53:166. doi: 10.1021/jm900861d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pemble CWt, et al. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achari A, et al. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:490. doi: 10.1038/nsb0697-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hampele IC, et al. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:21. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baca AM, Sirawaraporn R, Turley S, Sirawaraporn W, Hol WG. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:1193. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy C, Minnis D, Derrick JP. Biochem J. 2008;412:379. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science online.

- 17.Rebeille F, Macherel D, Mouillon JM, Garin J, Douce R. EMBO J. 1997;16:947. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mash EA, Gurria GM, Poulter CD. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1981;103:3927. doi: 10.1021/ja00445a056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poulter CD, Wiggins PL, Le AT. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1981;103:3926. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F. Chemical Reviews. 1988;88:899. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bock L, Miller GH, Schaper KJ, Seydel JK. J Med Chem. 1974;17:23. doi: 10.1021/jm00247a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roland S, Ferone R, Harvey RJ, Styles VL, Morrison RW. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:10337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romano KP, Ali A, Royer WE, Schiffer CA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006370107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.