Abstract

Direct and indirect exposure to gun violence have considerable consequences on individual health and well-being. However, no study has considered the effects of one’s social network on gunshot injury. This study investigates the relationship between an individual’s position in a high-risk social network and the probability of being a victim of a fatal or non-fatal gunshot wound by combining observational data from the police with records of fatal and non-fatal gunshot injuries among 763 individuals in Boston’s Cape Verdean community. A logistic regression approach is used to analyze the probability of being the victim of a fatal or non-fatal gunshot wound and whether such injury is related to age, gender, race, prior criminal activity, exposure to street gangs and other gunshot victims, density of one’s peer network, and the social distance to other gunshot victims. The findings demonstrate that 85 % all of the gunshot injuries in the sample occur within a single social network. Probability of gunshot victimization is related to one’s network distance to other gunshot victims: each network association removed from another gunshot victim reduces the odds of gunshot victimization by 25 % (odds ratio = 0.75; 95 % confidence interval, 0.65 to 0.87). This indirect exposure to gunshot victimization exerts an effect above and beyond the saturation of gunshot victimization in one’s peer network, age, prior criminal activity, and other individual and network variables.

Keywords: Social networks, Firearms, Gun violence, Homicide, Street gangs

Introduction

Gun violence remains a serious public health and safety problem in the USA. In 2009, a total of 9,146 people were murdered with firearms, and it is estimated another 48,158 were treated in hospitals for gunshot wounds received in assaults.1,2 Furthermore, exposure to gun violence and homicide is associated with a host of negative health outcomes including PTSD, depression, psychobiological distress, anxiety, cognitive functioning, and suicide, as well as other negative social behaviors such as school dropout, increased sexual activity, running away from home, and engagement in criminal and deviant behaviors.3–5

Leading social scientific explanations of gun violence commonly associate a heightened probability of gunshot victimization with individual (e.g., age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status), situational (e.g., the presence weapons, drugs, or alcohol), and community (e.g., residential mobility, population density, and income inequality) risk factors.6–9 Yet, the majority of individuals in high-risk populations never become gunshot victims. Indeed, research suggests that gun violence is intensely concentrated within high-risk populations.10,11 For example, recent studies in Boston found that from 1980 to 2008, only 5 % of city block faces and street corners experienced 74 % of gun assault incidents12 and that 50 % of homicide and nearly 75 % of gun assaults were driven by less than 1 % of the city’s youth population (aged 15–24), most of whom were gang involved and chronic offenders.13 To better understand how gunshot injury is distributed within high-risk populations, we conducted a study to determine whether the risk of gunshot victimization is related to characteristics of one’s social networks.

Studies on the health effects of social networks suggest that the clustering of certain health behaviors—such as obesity, smoking, and depression—is related not only to risk factors but also the contours of one’s social network.14–17 There are several reasons why the risk of gunshot victimization is related to one’s social network. First, interpersonal violence tends to occur between people who know each other suggesting that the context of social relationships is important in understanding the dynamics of gun violence.18,19 Second, the normative conditions surrounding gun use are transmitted through processes of peer influence, especially among young men with criminal histories.20 Third, guns themselves are durable objects that often diffuse through interpersonal connections suggesting that obtaining a gun—a necessary precursor to using a gun—must also occur through interpersonal relationships.21 Yet, despite the growing interest in social network analysis in the study of public health, no study has yet employed formal network models to understand how processes of peer influence and normative diffusion might influence the risk of gunshot injury.

The present study analyzes the salience of social networks on differential risks of gunshot injury among a population of 763 individuals in Boston. We examine several aspects of individuals’ social networks including: network density, the saturation of gang members in one’s network, and the social distance between an individual and other gunshot victims. We hypothesize that the structure and composition of an individual’s social network will influence one’s exposure to and risk of gunshot injury and thereby better explain the concentration of gunshot injury within risk high-risk populations.

Methods

Setting

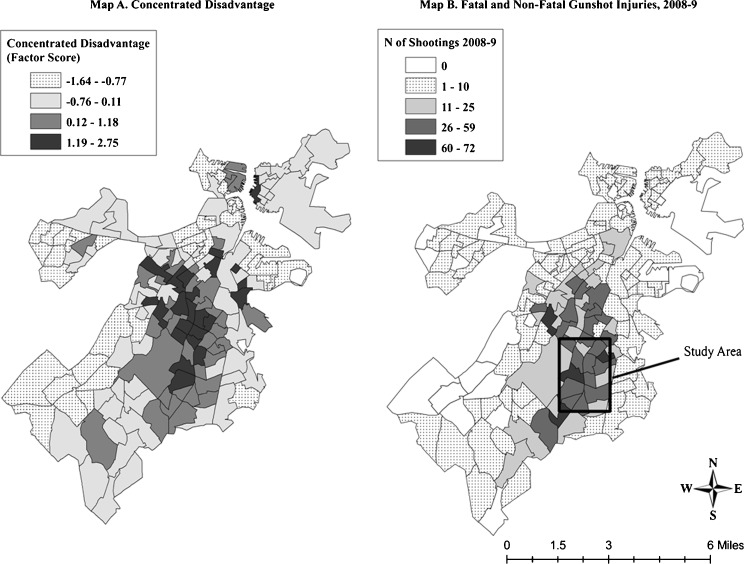

The present study examines gunshot victimization among a network of individuals from Boston’s Cape Verdean community (see, Figure 1). Cape Verde is an archipelago of islands located off the West Coast of Africa that was a colony of Portugal until 1975. As of 2000, Boston is home to an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 persons of Cape Verdean descent. Boston’s Cape Verdean population is concentrated in two communities—the Bowdoin-Geneva and Upham’s Corner neighborhoods—that are associated with many traditional violent crime “risk factors.” For example, in the Bowdoin-Geneva neighborhood 20 % of the population lives below the federal poverty line, 52 % live in a single-family household, and 42 % of the population has less than a high-school diploma.22 As seen in Figure 1, and consistent with prior neighborhood-level research.7,23 such socio-demographic characteristics tend to be higher in high-crime neighborhoods. Put another way, neighborhoods with high levels of socio-economic disadvantage also tend to have higher levels of crime and violence.

Figure 1.

Concentrated disadvantage and number of gunshot injuries in Boston.

The study communities were selected for three main reasons. First, as just described, the study area exhibits many of the aggregate level risk factors commonly associated with elevated levels of crime and violence. Second, as seen in Map B in Figure 1, the community also exhibits some of the highest concentration of gunshot injuries in Boston and, in fact, this area is driving much of the city’s current violence problem. In particular, the study neighborhoods struggle with youth street gang problems: fatal and non-fatal shootings involving Cape Verdean gang-involved youth more than tripled from 12 shootings in 1999 to 47 shootings in 2005.24 Finally, although the study area is situated ecologically within the a larger predominately African American section of Boston, violence within the study area tends to occur almost entirely between members of the Cape Verdean population.25 Thus, the study community represents a high-risk community in a larger urban area whose violence tends to occur within an identifiable population.

Data Collection

Data come from two sources provided by the Boston Police Department: Field Intelligence Observation (FIOs) cards and records of fatal and non-fatal gunshot injuries. FIOs are records of non-criminal encounters or observations made by the police; these reports include information such as: reason for the encounter, location, and the names of all individuals involved. Since these data include only observations by the police, the FIO data provide a conservative measure of one’s social networks as individuals have more friends and associates whom the police do not observe. Ties between individuals were derived for all situations in which two or more individuals were observed in each other’s presence by the police and recorded in FIO data—those two people observed by the police in the same time and place are taken to be “associates.” Extant qualitative research in sociology, anthropology, and criminology suggests that “hanging out”—standing on street corners while associating with one’s friends—is an important social behavior among young urban males as well as a key mechanism driving street-level violence.20,26–29

To generate the social networks of high-risk individuals in the study communities, we employed a two-step sampling method frequently used in the study of other high-risk populations such as drug users and sex workers.30 The initial sampling seeds consisted of the entire population of Cape Verdean gang members known to the police (N = 238). Step 1 entailed pulling all FIOs in the year 2008 for these 238 individuals to generate a list of their immediate associates. This step was repeated (Step 2) to gather the “friends’ friends” of the original seeds to create a final social network of 763 individuals. Previous research suggests that such a two-step approach adequately captures the vast majority of information necessary to understand the underling social processes.31

The FIO data were then merged with data on all known fatal and non-fatal gunshot injuries reported to the police enabling us to determine which individuals in our social network were the victims of gunshot violence in the years 2008–2009. During the study time period, two of the individuals in the sample were the victims of fatal gunshot wounds and 38 were victims of non-fatal injuries.

Models

We use rare event logistic regression32 to model the determinates of gunshot victimization in the sample population. Two sets of models are presented. The first set presents the results on the entire population of 763 individuals, while the second set presents the results of a subsample of 579 of the population that comprise a single larger network. To account for temporal ordering, the network was constructed using data from 2008 and regressed on the victimization data for 2008–2009. Network calculations and visualizations were conducted using the statnet software in the statistical package, R.33 Regression analyses were conducted using Stata 10.34

Variables

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and range for all variables used in our analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for each variable used in descriptive and regression analyses

| Mean (SD) | Range (minimum and maximum) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| Fatal or non-fatal gunshot victim | 0.05 (0.22) | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Independent variables | ||

| Degree: number of observed ties | 2.89 (3.22) | 0, 24 |

| Age: age in years | 24.87 (6.33) | 15, 53 |

| Gender: whether or not the individual is female (as compared with male) | 0.06 (0.24) | 0 = male, 1 = female |

| Cape Verdean: whether or not the individual is of Cape Verde decent (as compared with all other races and ethnicities) | 0.50 (0.50) | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Prior arrest: whether or not individual has at least one prior arrest | 0.31 (0.46) | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Ego-network density: percentage of all network ties that are present as a proportion of all possible ties. | 0.23 (0.37) | 0, 1 |

| Gang member: individual identified by police as a gang member. | 0.311 (0.46) | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Percent of gang members in network: percent of Alters who are gang members as identified by police | 0.45 (0.41) | 0, 1 |

| Percent of network containing shooting victim: the percentage of individuals immediate social network that contains shooting victims | 0.08 (0.21) | 0, 1 |

| Distance to shooting/homicide victim: the average shortest distance between an individual and a shooting/homicide victim | 4.69 (2.91) | 0, 10.74 |

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether or not an individual was the victim of either a fatal or non-fatal gunshot wound in 2008–2009. Approximately 5 % of the sample were victims of gun violence. The current study combines fatal and non-fatal injuries; analysis of only non-fatal shooting found no discernible differences in the results.

Independent Variables

Individual Level Covariates

Our models include several individual-level control variables associated with gun violence: age, gender, race/ethnicity, and whether or not the individual has ever been arrested. Age is consistently a strong predictor of violent victimization: rates of homicide victimization peak between 18 and 24, and decline steadily thereafter. We square age (in years) to capture this non-linear relationship. Gender is measured as a binary variable (1 = female and 0 = male). The vast majority of network members are male (94 %). Ethnicity is measured as a binary variable indicating whether or not the subject was of Cape Verdean ancestry (1 = yes and 0 = no). Half of the study population is of Cape Verdean decent and the remainder is mainly African-American. Finally, we include a binary dummy variable to indicate whether or not the subject has at least one prior arrest with the Boston Police Department (1 = yes and 0 = no). A full third of the sample has at least one prior arrest.

Network Measures

On average, any individual in the network has ties to approximately three associates, though the standard deviation is equally large. This distribution of ties in the network—presented in the Appendix—is consistent with prior research that finds that most individuals in networks have a small number of ties, while a small number of individuals have an exceedingly large number of ties.35 In the present data, however, some caution is in order as the ties themselves are based on police observations—i.e., the number of ties may be influenced how police go about their duties and investigations.36 As such, we weigh our sample according to this degree distribution to account for any bias attributable to policing efforts.

Four social network measures are included in the analyses: network density, the percentage of one’s associates who are known gang members, the percentage of one’s immediate associates who have been gunshot victims, and the average “social distance” from the subject to other shooting victims.

Network density is a basic property that reflects the overall intensity of the connected actors: the more connected the network, the greater the density.37 Dense networks are often associated with cohesive subgroupings and cliques.38 Formally, network density is measured as the sum of ties that are present in the network divided by the possible number of ties.37 Here, we measure the ego-network density as the density of ties in the immediate social network surrounding each individual.37

We also measure the percentage of one’s immediate associates who are gang members. This measure extends the prior research on the negative consequences of gang membership39 by capturing a saturation effect: greater exposure to gang members in one’s social network should also increase one’s exposure to gun violence.

Exposure to gunshot violence is measured in two ways. First, we measure the effect of exposure to gunshot violence in one’s immediate social network as the percentage of an individual’s immediate associates who were gunshot victims—i.e., someone whom they were observed associating with in public. Second, we extend this idea to include a measure of social distance to gunshot victims, measured as the average number of shortest paths (mean geodesic distance) from the subject to all gunshot victims in the social network.37 In large social networks, individuals can be connected indirectly in many different ways and, therefore, information and influence can potentially travel different paths in the network between any two individuals. Research demonstrates that a wide variety of health and social behaviors are affected by people in the our social networks who are a few handshakes removed.14,40

Formally, we measure social distance as the mean geodesic distance between each individual in the sample to all gunshot victims. The geodesic distance refers to the shortest path between two nodes, where the distance between two nodes ni and nj is measured simply as d(i, j). The shortest distance, then, is the smallest value of d(i, j). We calculated the measure in the following manner. First, we computed the entire distance matrix for the social network; in this case a 786 by 786 matrix where each cell value represents the distance d(i, j) between two nodes. These data are symmetric meaning, that in all cases d(i,j) = d(j, i). Next we complied a binary vector of the 786 individuals in the network indicating whether each of the individuals was the victim of a shooting (1 = yes and 0 = no). Finally, because there are multiple shooting victims and multiple paths connecting individuals to these multiple shooting victims, we calculated the mean average geodesic distance of all possible shortest distances to all shooting victims; such an approach thus allows us to capture all potential avenues of indirect exposure. For disconnected parts of the network, we calculate this measure within each component. Our basic working hypothesis in this study is that individuals who are, on average, closer to shooting victims will be at greater risk of becoming victims themselves.

Results

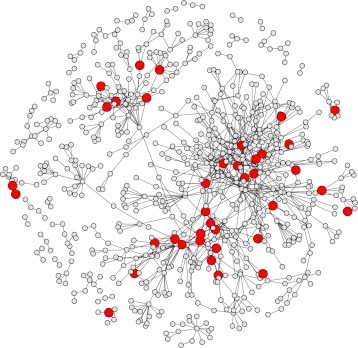

The network of 763 individuals generated from the sampling method is presented in Figure 2. Each of the nodes represents a unique individual and each of the ties linking two nodes indicates at least one observation of two individuals observed socializing together. A total of 1,869 ties were extracted from the data. Gunshot victims are represented as the larger red nodes in the network. Figure 2 is comprised of 57 unique subnetworks (components), although 76 % of individuals are connected in the single large network consisting of 579 individuals (large component). The majority of gunshot victims (85 %) are found in the large component . The average geodesic distance between any individual in the network and a gunshot victim is 4.69. Taken together, these findings suggest that the majority of individuals in this network are connected in a single large network and, on average, any person is roughly five handshakes removed from a gunshot victim.

Figure 2.

The social network of high-risk individuals in Cape Verdean community in Boston, 2008.

Predicting Gunshot Victimization

Table 2 shows the odds ratios (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for models that regressed gunshot victimization on the full set of explanatory variables on both the entire network and the largest component. Examination of the individual-level predictors for both models show that, the odds of being a gunshot victim decreases with age (OR= 0.99; 95 % CI, 0.997 to 0.999) and increases with prior contact with the criminal justice system (OR = 1.85; 95 % CI, 1.31 to 2.63). As expected, females in the network are less likely to be victims (OR = 0.85; 95 % CI, 0.299 to 2.41) and those of Cape Verdean decent are more likely to be victims (OR = 1.34; 95 % CI, 0.900 to 2.00). However, neither of these variables attain statistical significance, reflecting the gender and racial homogeneity of the sample.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of shooting/homicide victimization on individual and network characteristics

| Probability of gunshot victimization (OR (95 % CI)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete network (N = 763) | Largest component (N = 579) | |||

| OR (95 % CI) | p value | OR (95 % CI) | p value | |

| Individual level variables | ||||

| Age 2 | 0.998 (0.997, 0.999) | 0.000 | 0.998 (0.997, 0.999) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.85 (0.299, 2.41) | 0.761 | 1.21 (0.461, 2.56) | 0.719 |

| Cape Verdean | 1.34 (0.900, 2.00) | 0.148 | 1.03 (0.648, 1.66) | 0.871 |

| Ever been arrested | 1.85 (1.31, 2.63) | 0.001 | 1.88 (1.30, 2.73) | 0.001 |

| Network variables | ||||

| Ego-network density | 0.788 (0.441, 1.40) | 0.421 | 0.646 (0.323, 1.291) | 0.217 |

| Percent of gang members in network | 1.66 (0.991, 2.68) | 0.054 | 1.39 (0.765, 2.54) | 0.276 |

| Percent of immediate alters who have been shot | 2.44 (1.11, 5.36) | 0.026 | 1.39 (0.557,3.45) | 0.481 |

| Distance to shooting/homicide victim | 0.912 (0.844, .985) | 0.024 | 0.754 (0.654, 0.869) | 0.000 |

| Log likelihood | −697.96 | −636.969 | ||

| LR Chi-square | 96.77 | 105.6 | ||

Ego-network density in both models is negatively related to gunshot victimization suggesting that density may, in fact, be protective of victimization (OR = 0.79; 95 % CI, 0.441 to 1.40); the p value of this variable, however, suggests that this effect is not significantly different than zero. When considering only the complete network, the saturation of gang members increases one’s odds of being shot (OR = 1.66; 95 % CI, 0.991 to 2.68), although the statistical significance of this effect drops when considering only the large component (OR = 1.39; 95 % CI, 0.765 to 2.54).

The magnitude of our two variables pertaining to network exposure to gunshot injuries differs slightly between the models in Table 2 of immediate alters who have been shot greatly increases one’s odds of also being a gunshot victim (OR = 2.44; 95 % CI, 1.11 to 5.36)): a 1 % increase in the number of one’s friends who are gunshot victims increases one’s own odds of victimization by approximately 144 %. This effect diminishes in the model for only the large network (OR = 1.38; 95 % CI, 0.557 to 3.45) and loses its statistical significance (p value = 0.481). This loss of statistical significance highlights the fact that individuals in smaller networks (i.e., not members of the larger component) have fewer avenues of indirect exposure and, therefore, direct exposure has a much more potent influence.

Both models in Table 2 support our main hypothesis that social distance is related to gun victimization: the closer one is to a gunshot victim, the greater the probability of one’s own victimization, net of individual and other network characteristics. In the whole network model, every one connection away from a shooting victim decreases the odds of getting shot by 8.8 % (OR = 0.912; 95 % CI, 1.11 to 5.36). This effect is more pronounced in the large component: every one connection removed from a gunshot victim decreasing one’s odds of getting shot by approximately 25 % (OR = 0.754; 95 % CI, 0.654 to 0.869). This relationship between distance to a shooting victim and probability of gunshot victimization is summarized in Figure 3 where the x-axis indicates the average distance to a shooting victim and the y-axis indicates the predicted probability of gunshot injury in the largest component model in Table 2. Because the large component is completely connected and contains the majority of shooting victims, the x-axis begins at four demonstrating that (a) everyone in the large networks is indirectly connected to a shooting victim and (b) the shortest average path to any victim is four connections. Figure 2 reveals two important features related to social distance. First, the association between social distance and the probability of gunshot victimization is more pronounced among gang members, suggesting that gang members may occupy unique positions within such networks that place them at greater risk. Second, for both gang and non-gang members, the effect of the risk begins to level off after approximately five network degrees. Regardless, the effect of indirect exposure to gunshot injuries is pronounced for both gang and non-gang members.

Figure 3.

The relationship between the predicted probability of being a shooting/homicide victim and distance to another shooting/homicide victim.

Discussion

Our data on high-risk individuals Boston’s Cape Verdean community reveals a social network of young men with a highly elevated risk of gunshot victimization. Network analysis shows the existence of a social network consisting of 763 individuals, the majority of whom are all connected in a single large network and, on average, individuals in this network are less than five handshakes away from the victim of a gun homicide or non-fatal shooting. Our findings demonstrate that the effect of this distance to a shooting victim greatly increases an individual’s own odds of becoming a subsequent gunshot victim: the closer one is to a gunshot victim, the greater the probability that person will be shot. Indeed, each network step away from a gunshot victim decreases one’s odds of getting shot by approximately 25 %.

The findings of this study are limited in three ways. First, our sampling clearly does not identify all individuals at risk of gunshot victimization. Situations not visible to police investigation—such as unreported domestic violence incidents—would not be captured in our data. Second, the use of FIO data circumscribes our measurement of social networks to those ties witnessed firsthand by police and, therefore, we probably underestimate the extent of social networks. Third, our findings may also be confined to the unique character of Boston’s Cape Verdean neighborhoods. However, these communities share many similarities with other high-crime and socially disadvantaged urban neighborhoods and recent research suggests that the network patterns described here extend to gang violence in Chicago.41

Limitations notwithstanding, these results imply that social networks are relevant in understanding the risk of gunshot injury in urban areas. The contours of our social networks—even when we cannot see them—affects our behavior. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the risk of gunshot victimization is not evenly distributed within high-risk populations. In the present study, those individuals in the largest social network, for instance, are at a much greater risk of victimization than either those in the smaller disconnected networks or of the general neighborhood population in large part because of the ways in which people are situated in social networks. How and why such networks affect the ways in which we assess the risk of gunshot injury is of importance for future research and public health. In particular, gun violence reduction strategies might be better served by directing intervention and prevention efforts towards individuals within high-risk social networks.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Commissioner Edward F. Davis, Superintendent Paul Fitzgerald, and Johnathan Sikorski of the Boston Police Department for their support and assistance in acquiring some of the data presented here. All authors of this project had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis. Professor Papachristos conducted all network and regression analysis. Professor Papachristos and Mr. Hureau coded and prepared all data. All of the authors shared in study design and writing of the results.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by a Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholar’s Fellowship and a grant awarded by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation both awarded to Professor Papachristos.

Appendix A

Figure 4.

The distribution of the number of network ties.

References

- 1.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Reports (http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2009/index.html). 2009. Accessed 18 December, 2010.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. (http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nonfatal.html). 2010. Accessed 18 December, 2010.

- 3.Sharkey P. The acute effect of local homicides on children’s cognitive performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(26):11733–11738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000690107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morenoff J. Neighborhood mechanisms and the spatial dynamics of birth weight. Am J Sociol. 2003;108(5):976–1017. doi: 10.1086/374405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook PJ, Laub JH. After the epidemic: recent trends in youth violence in the United States. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson RD, Krivo LJ. Macrostructural analyses of race, ethnicity, and violent crime: recent lessons and new directions for research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2005;31(1):331–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones-Webb R, Wall M. Neighborhood racial/ethnic concentration, social disadvantage, and homicide risk: an ecological analysis of 10 U.S. cities. J Urban Health. 2008;8(5):662–676. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9302-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duggan M. More guns, more crime. J Polit Econ. 2001;109(5):1086–1114. doi: 10.1086/322833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braga AA. Problem-oriented policing and crime prevention (2nd edition) Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisburd DL, Bushway S, Lum C, Yang S-M. Trajectories of crime at places: a longitudinal study of street segments in the city of seattle. Criminology. 2004;42:283–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00521.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braga AA, Papachristos AV, Hureau D. The concentration and stability of gun violence at micro places in Boston, 1980–2008. J Quant Criminol. 2010;26(1):33–53. doi: 10.1007/s10940-009-9082-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braga AA, Hureau D, Winship C. Losing faith? Police, black churches, and the resurgence of youth violence in Boston. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. 2008;6:141–172. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bearman P, Moody J. Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):89–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cobb NK, Grahm AL, Abrams DB. Social network structure of a large online community for smoking cessation. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(7):1282–1289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith KP, Christakis N. Social networks and health. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:405–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felson RB, Steadman HJ. Situational factors in disputes leading to criminal violence. Criminology. 1983;21(1):59–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1983.tb00251.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luckenbill DF. Criminal homicide as a situated transaction. Soc Probl. 1977;25(2):176–186. doi: 10.2307/800293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagan J, Wilkinson DL. Guns, youth violence, and social identity in inner cities. Crime and Justice. 1998;24:105–188. doi: 10.1086/449279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook PJ, Ludwig J, Venkatesh SA, Braga AA. Underground gun markets. Econ J. 2007;117:558–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02098.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bureau USC. Summary File 3 (SF3) 2000.

- 23.Sampson RJ, Lauritsen J, eds. Violent victimization and offending: individual-, situational-, and community-level risk factors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. Council NR, ed. Understanding and Preventing Violence: Social Influences No. 3.

- 24.Hureau D. Building community partnerships and reducing youth violence in Boston’s Cape Verdean neighborhoods. Cambridge, MA: The Kennedy School of Government, Harvard; 2006.

- 25.Papachristos AV, David H, Braga AA. Conflict and the Corner: The Impact of Intergroup Conflict and Geographic Turf on Gang Violence. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1722329 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1722329. 2010. Accessed 8 September, 2010.

- 26.Anderson E. Code of the streets. New York: Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horowitz R. Honor and the American Dream. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannerz U. Soulside: inquiries into ghetto culture and community. New York: Columbia University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkatesh SA. Off the books: the underground economy of the urban poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34:193. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsden PV. Recent developments in network measurements. In: Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wasserman S, editors. Models and methods in social network analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.King G, Zeng L. Logistic regression in rare events. Polit Anal. 2001;9(2):137–163. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a004868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.statnet: Software Tools for the Statistical Modeling of Network Data [computer program]. Version http://statnetproject.org2003.

- 34.Release 10 [computer program] College Station: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song CM, Havlin S, Makse HA. Self-similarity of complex networks. Nature. 2005;433(7024):392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature03248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morselli C. Inside criminal networks. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman JS. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(Supplement: Organizations and Institutions: Sociological and Economic Approaches to the Analysis of Social Structure):S95–S120.

- 39.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K. Gangs and delinquency in development perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Payne DC, Cornwell B. Reconsidering peer influences on delinquency: do less proximate contacts matter? J Quant Criminol. 2007;23:127–149. doi: 10.1007/s10940-006-9022-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papachristos AV. Murder by structure: dominance relations and the social structure of gang homicide. Am J Sociol. 2009;115(1):74–128. doi: 10.1086/597791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]