Abstract

Globally, health and social inequities are growing and are created, actively maintained, and aggravated by existing policies and practices. The call for evidence-based policy making to address this injustice seems a promising strategy to facilitate a reversal of existing strategies and the design of new effective programming. Acting on evidence to address inequities requires congruence between identifying the major drivers of disparities and the study of their causes and solutions. Yet, current research on inequities tends to focus on documenting disparities among individuals or subpopulations with little focus on identifying the macro-social causes of adverse population health. Moreover, the research base falls far short of a focus on the solutions to the complex multilevel drivers of disparities. This paper focuses upon recommendations to refocus and improve the public health research evidence generated to inform and create strong evidence-based recommendations for improving population health.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, Health inequalities, Evidence, Social epidemiology

Introduction

Globally, health inequities are growing.1,2 These inequities in the local, national, and global arenas are created, actively maintained, and aggravated by existing policies and practices. The call for evidence-based policy making to address this injustice seems a promising strategy to facilitate a reversal of existing practices and the design of new effective interventions.1 Yet, the field of knowledge translation has long documented the chasm between researcher-generated evidence about health problems or their solutions on the one side and awareness and utilization of this body of knowledge by policy makers and program planners on the other.3–5 While this knowledge translation literature has largely been concerned with the clinical practice setting, there has been increasing focus on population and public health.6–11 Worries about researchers and practitioners or policy makers operating in different universes have been the basis of research and commentary in and outside of the health fields for some time.3,4 According to this growing literature, problems contributing to these gaps include a lack of understanding among researchers about the process of policy making and policy makers’ evidence needs; a lack of knowledge among policy makers or practitioners about relevant scientific evidence, including syntheses of evidence to inform program planning or policy; the absence of policy concerns from systems of reward and motivation among academic researchers; and insufficient interaction between researchers and policy makers to clarify and match evidence needs. There has been ample response in the form of recommendations, with varying feasibility, to remedy the situation, such as creation of policy briefs summarizing research evidence, better “integration” of policy makers or practitioners to co-create knowledge and evidence, providing more guidance to practitioners or policy makers about how to use and implement the scientific evidence, and teaching researchers about the policy making process.12–14 Moreover, diagnoses of the drivers of “know-do gaps” are increasingly responsive to heightened concern over health inequities. This concern now also shapes knowledge translation frameworks and agendas.6,9 In other words, alarm over the growth and intractability of health and social inequities is changing health knowledge, especially during this worldwide economic downturn, where the gaps continue to widen and the wealthy are taking an ever greater share of the pie.1,15,16 Acting on evidence to address inequities requires congruence between identifying the major drivers of disparities and the study of their causes and solutions. Unfortunately, if we were to derive information about the drivers of inequity from the public health or epidemiologic literature, we might conclude that they all occur at the individual level, given the excess of studies in the disparities literature focusing on personal attributes or behaviors.17 Thus, a quick review of the “causes of the causes” of disparities will help frame a subsequent discussion about the research that public health scientists might generate to inform solutions to the growth of health inequities.

Health and Social Inequities: What Are the Major Trends and Causes?

It is no secret that we are in the middle of a worldwide economic recession characterized by exceptional levels of unemployment, a rise in homelessness and housing instability, and widening wealth gaps. The media is awash in headlines reflecting the consequences of the current economic downturn: “US Housing Crisis Is Now Worse Than Great Depression,”18 “More Middle Class Families ‘Will Become Homeless’ Due to Recession,”19 “Length of Unemployment Continues to Break Records.”20 The article from which the latter attention grabber was drawn estimates that, on average, unemployed people must now search for jobs 40 or more weeks. Yet even prior to the recession, large proportions of the global population were experiencing chronic poverty and the consequences of the erosion of many countries’ social safety nets.21 In 2009, the WHO’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health released their report, Closing the Gap in a Generation, which studied the causes of growing global social and health disparities.1 The report identified several drivers of and solutions to inequities, examples of which are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Call for action on the social determinants of health to close global health disparities

| Greater availability of affordable housing through investment in urban slum upgrades, including provision of water, sanitation, and electricity |

| Full and fair employment and decent work, resulting from employment being made a central goal of national and international social and economic policy making |

| Secure work for men and women with a living wage that takes into account the real and current cost of healthy living, ensured by appropriate economic and social policies |

| Universal comprehensive social protection policies |

| Progressive taxation, built by achieving greater capacity in this area at the national level |

| Healthy and safe behaviors to be promoted equitably, including promotion of physical activity, encouragement for healthy eating, and reduction of violence and crime through good environmental design and regulatory controls, including control of alcohol outlets |

| Increased global aid at 0.7 % of GDP, to be achieved by nations honoring existing commitments |

| Health care systems based on the principles of equity, disease prevention, and health promotion with universal coverage and focusing on primary health care, regardless of ability to pay |

| Health equity impact assessments of major global, regional, and bilateral economic agreements9,76 |

| Empowerment of all groups in society through fair representation in decision making |

| Gender equity, to be promoted through enforced legislation |

Examples from the WHO Report on Closing the Gap in a Generation, 20091

These actions proposed by the WHO’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDOH) reflect years of synthesizing the scientific evidence on “causes of the causes” of health disparities. Each action reflects the key issues plaguing nations around the globe during the economic crisis, like employment and taxation, which are also topics of discussion and debate.15,16,22–24 Unfortunately, implementation of such policies currently appears to be on the losing end of policy making discussions in favor of policies that widen the economic gaps between a rich minority and the rest of the population.25

What Are the Current Gaps in Evidence in the Epidemiology and Public Health Literature to Inform Solutions to SDOH?

A major goal of public health research is to generate evidence to support action to improve population well-being, which includes evidence to address social determinants of health. But just how well is public health research, and epidemiologic research in particular, as it is the foundational science of public health, doing in terms of producing solid evidence to inform decision making about determinants of and solutions to health disparities? We might have the greatest expectations of social epidemiology to generate ample evidence to inform solutions to social and health disparities, given its focus on the social determinants of health. Yet, a great proportion of social epidemiologic research is on the downstream determinants of health, and too few studies examine the macro-social determinants.17,26–29 Moreover, many studies are descriptive, in that they document associations between social determinants and well-being, while too few propose or assess specific social interventions. One epidemiologist recently noted that while our field faces “a feast of descriptive studies of socio-economic causes of ill health we still face a famine of evaluative intervention studies.”30 Thus, to generate evidence on solutions to the problem of growing health disparities, researchers within our field will require newer frameworks to inform our work and newer methods to support alternative research agendas.17

Public health researchers should generate evidence that is closely aligned with what policy makers and program planners can use. Fortunately, a growing literature now describes the types of evidence most needed by those whose work is to design and implement policies and programs to address social and health disparities. Selected learnings from this literature are presented below, along with a discussion of whether and how public health and epidemiology researchers can match those particular evidence needs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Type of evidence that public health and epidemiology scientists should produce for solutions to complex social determinants of health and health inequities

| A comprehensive picture on the multilevel determinants of health inequities, produced by piecing together from different types and sources of evidence |

| Evaluations of existing macro-social policies and programs that (1) go beyond demonstrating effectiveness to reveal underlying theories of causation and/or uncover the specific “effective” ingredients in programs and policies and (2) provide short- and long-term guidance for their implementation, tailoring, and adaptation |

What Specific Evidence Do Policy Makers and Program Planners Who Are Concerned with Social Determinants Want?

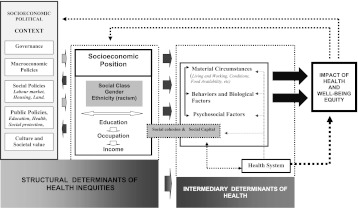

Policy makers and researchers recognize the complexity of social determinants of health (see Figure 1). Not only are drivers of health disparities operating at multiple levels but they also impact upon developmental trajectories and operate over the life course.28,31,32 While data of all types exist to describe different aspects of the social determinants impact on individual well-being, studies typically generate evidence for one small piece of the larger picture. Epidemiology, a disease oriented field, tends toward specialization in the study of particular diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer) or exposures (e.g., violence, workplaces). Rarely is the evidence pieced together to examine shared or unique pathways and determinants. Even reviews of the literature often focus on one disease or one exposure. And while diverse evidence exists across public health disciplines, too rarely are the pieces put together to create a comprehensive view of social determinants.33–35 Yet, policy makers and those who seek to act on the evidence need more information on how a specific program or policy might impact upon policies/programs within and across sectors and vice versa.33,34 When asked about the types of evidence that might have the greatest impact on policy making, senior researchers have suggested that one way to improve the presentation of evidence to policy makers is to assemble an “evidence jigsaw.”11,35 How would this jigsaw look? Data and evidence of relevance to policy making and program design would be pulled from myriad sources and even disciplines, then woven together into a comprehensive, coherent description of their action and interaction. One barrier that may have precluded such efforts in the past is scientists’ preoccupation with the “evidence hierarchy” (i.e., with Randomized Trials at the top). While this issue may be important for ensuring maintenance of professional standards, policy makers are prone to use all types of evidence to inform their work, with no regard to the scientific hierarchies often imposed by epidemiologists.7,11 Research emerging from transdisciplinary efforts, as opposed to multi- or interdisciplinary research, might facilitate the generation of this type of integrated knowledge. Transdisciplinary research includes researchers from varying disciplines, policy makers, or members of affected communities who collaborate “using shared conceptual frameworks drawing together disciplinary theories, concepts, and approaches to address a common problem” (p. 1351).36 Because scientists are often experts in their own field and are best at evaluating evidence generated from methods within their own disciplines, transdisciplinary teams enable the best evidence to be brought forth and combined to create a more holistic picture of the problem for policy makers and program planners to consider.36,37

FIGURE 1.

CSDOH framework on health inequity.

Second, policy makers need greater evaluation data to inform their work. Thus, in addition to identifying the key macro-social drivers of health and health disparities, policy makers, and program planners in particular, seek evidence that tells them how these factors impact upon population and individual well-being.8,17,38,39 While public health and epidemiologic researchers have done a better job in this area with the emergence of systematic reviews, including reviews of social interventions,40 this may not be enough. Specifically, policy makers, when asked about major gaps in evaluation knowledge, have reported that “lack of evidence may extend beyond issues of effectiveness.” They “pointed to a need for stronger theoretical underpinnings for existing quantitative research and for methodological work on policy evaluation, to take account of plausible causal pathways to ill health” (p. 814).11 In other words, policy makers need evaluations that can hold water at the policy level, that can help them link the macro-social to action in a given area. Thus, as eye opening as the book Spirit Level has been in providing powerful empirical support for the key role of inequality (versus poverty) in determining population well-being, it is unclear how jurisdictions might implement the specific interventions the authors call for to reduce inequalities, such as minimizing the gap between worker and CEO pay, more widespread use of employee owned companies, increasing the minimum wage and increasing taxes on the wealthy.2 This observation has been confirmed by prominent health disparities researchers, who have noted that it is important to “nurture an evaluation culture,” even suggesting that all programs have a mandatory evaluation requirement,35 as was the case in the past with some national programs (e.g., 41,42). If all current policies and programs that have the potential to impact on social well-being were required to be evaluated, we might begin to accumulate the evidence needed to inform decisions to improve population health.

A large proportion of epidemiologic research is, indeed, devoted to randomized trials, even of social interventions and community trials, as well as to evidence syntheses of interventions and programs concerned with the social determinants of health. Yet policy makers and program planners are asking for specific kinds of evidence to emerge from these efforts. It is not enough to know that a particular program or policy is effective. It is critical to know just how and why it is effective, revealing the exact ingredients of its success.43 This information can enable effective implementation of policies or programs, or support suitable program adaptations. In epidemiology, evidence syntheses often focus on how effective programs are, with less or no attention to synthesizing the underlying theories of programs.38 Calls for greater study of theories in evaluation started late in the last century (e.g., 44), and since then, evaluation of program theory has grown.45 The recent surge in realist evaluations and realist reviews of complex health programs that focus on “what works, for whom, and why” is also evidence of the growth of this trend.46–50 For example, in the area of partner violence screening in health care settings, evidence from at least six traditional systematic reviews from the period 2003 to 2009 were being interpreted by evidence synthesis bodies as providing insufficient evidence to support screening efforts.51 Yet, a reevaluation of those data using realist review methodology, which focused on the theory of why and how screening programs worked, identified strong evidence to support programs with multiple “comprehensive” program components. While far from perfect, such approaches can augment and improve upon the current evidence being generated about programs and their effectiveness.38 The key is to generate more evaluative evidence that taps into theory and reveals the key program mechanisms that facilitate improvement in outcomes in a way that also focuses on upstream determinants of health and health disparities.

This brings us to the second area of evaluation research where scientists can improve the evidence that they make available to policy makers and program planners: implementation. One of the major challenges identified in the establishment of complex programs is the lack of specific guidance and support for implementation of program components, or suitable adaptations while maintaining fidelity to efficacious program components.52,53 This may be particularly true for complex, multi-sector, cross-sectoral interventions.10 One approach that combines evaluation of complex programs with built-in periods of assessment and readjustment is Developmental Evaluation.54,55 This approach has been used for complex social interventions to both facilitate early learning and course correction of the intervention and to facilitate the determination of the key ingredients of both success and failure in multiple contexts. The At Home/Chez soi study in Canada, a complex multi-sector, multilevel, “Housing First” (HF) intervention for homeless adults with severe mental illness, is one example. This $100 million program, implemented in five sites with diverse homeless populations, services, and resources across Canada, is using multi-method developmental evaluation to produce knowledge about how HF works and how best to implement HF in each of these diverse settings while maintaining program fidelity.56,57 Important lessons have already been learned about mobilization and coordination across multiple sectors when supporting this population.56 This information, in turn, will be used to reveal the key components that are required for sustainability and scaling up supports to homeless populations across Canada. This large-scale intervention benefits from the recent advances in methods and approaches appearing in the evaluation literature, in particular on the social determinants of health.17,32 Previous large-scale efforts, such as the Healthy Start infant mortality prevention program that provided $441.5 million to 15 demonstration programs across the USA from 1991 to 1997,58 were evaluated for their ultimate impact but revealed too little about which aspects of the programs worked and how successful components could be adapted for implementation elsewhere.

How Can We Apply These Recommendations to Generate Stronger Evidence Now?

The purpose of this paper is not to set out a comprehensive agenda for the future of policy-relevant public health and epidemiologic research. Still, we can apply the three recommendations described above to examples of how they might generate actionable knowledge about how to modify or strengthen existing policies to reduce disparities. There is no shortage of candidates of policies directly contributing to or shaping social and health inequities, as outlined in any number of documents, reports, academic papers, and political policy agendas.2,15,16,22,59

With regards to piecing together disparate evidence to create a comprehensive view of the possible solutions to a problem (the jigsaw), we might turn to the issue of tobacco. Tobacco consumption is one of the major causes of significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Given the limited uptake and effectiveness of smoking cessation efforts, the key to reducing its impact on morbidity and mortality is to promote primary prevention efforts. Since almost 90 % of smokers start their habits before age 18, at least in high-income countries, we need to consider primary prevention efforts toward teens and pre-teens. Yet, bringing together the evidence on the vast number of interventions targeting youth, which operate at multiple levels, in order to form a more coherent picture of the best options for investing in primary prevention is daunting. Furthermore, given that youth smoking rates can vary substantially by geographic area (provincial rates vary by up to 20 percentage points),60 the specific context of program implementation must be taken into consideration. Table 3 provides examples of interventions specifically relevant for prevention of tobacco use among youth. Some interventions listed actually increase tobacco use and need to be modified or eliminated to minimize their effects on smoking.61–67

Table 3.

Examples of programs that may prevent youth tobacco consumption

| Level of intervention | Example of intervention |

|---|---|

| Youth | Smoking cessation programs for youth |

| Advertisements to youth about tobacco (which increases youth consumption) | |

| Penalties for possession or use of tobacco by youth | |

| Family | Family-based programs to strengthen non-smoking attitudes/behaviors |

| Community | School-based educational programs |

| Laws restricting tobacco sales to youth | |

| Mass media campaigns to discourage youth smoking | |

| Multi-component school or community programs to reduce youth tobacco uptake | |

| Sporting organization policies on smoking | |

| Regulation of indoor air of facilities, including schools, with regard to tobacco | |

Each of the interventions in the table has been evaluated for its effectiveness in preventing (or promoting) consumption of tobacco by youth. Conclusions about program or policy effectiveness have been reached using the widely accepted evidence hierarchies, with randomized trials purported to provide the strongest evidence. The strongest evidence is in favor of smoking cessation programs, as many youth smokers express a desire and/or have attempted to quit.63 Exposure to pro smoking ads increases the risk of smoking among youth and could be more strictly regulated.64 Implementing smoke-free indoor spaces and excise taxes on tobacco products are two promising interventions.62 But mixed results have been found for the effectiveness of laws to limit youth access to tobacco via restrictions on retailers.66 Not only does the strength of evidence for these myriad programs vary but no programs, except for the multi-component community programs that include several “sectors” within a given community, also have been examined for joint effects of efforts to prevent youth tobacco consumption. While summaries of this evidence exist separately for each type of program (i.e., Cochrane reviews), or even as a review of program options (IOM), these provide little guidance about which interventions or policies should receive the highest priority for a given community, or how to develop a program of interventions to build on existing community strengths. Despite the wealth of evidence then, it is currently too easy to miss the mark in terms of selecting and implementing the right combination of programs and policies to prevent and reduce smoking among youth. As well, while this evidence has been generated according to the highest academic standards, there is likely other relevant evidence, generated with less rigor but of high relevance to local settings, and this should be included in a comprehensive view of the options to addressing smoking among youth. In the area of generating more evidence on upstream determinants of health and social inequalities, there are multiple policies and practices that could serve as candidates for examination. There is also strong support, among all sectors of society, to take action on macro-social determinants to ensure a more equitable society.68 A long-standing tension remains over the question of what strategy to adopt to best address issues such as growing wealth inequalities, underemployment, and poverty: increase social spending on programs like welfare, housing, or unemployment benefits, or institute tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy minority and wait for benefits to “trickle down” to those with less by “stimulating” spending and the economy? In recent times, tax cuts and even “bailouts” of the wealthy have been the predominant strategy, while there has been no growth or, worse, cuts in social spending. Wages among the middle classes have been declining over the past several decades, and the minimum wage has not been substantially increased.16,69 These policies and programs could be fully evaluated to assess their relative contributions to population well-being and growth of social and health disparities over time. Only limited evaluations of such policies and programs are currently underway, allowing only glimpses into narrow questions about the success of policy impact on disparities. The data suggest that tax cuts for the wealthy is a major driver of growing income disparities, but this growing trend is not well linked to population health. Nor have the simultaneous trends of falling middle-class wages and the chronically low minimum wage been linked to population well-being. Rigorous evaluations of these complex policies and practices are needed if researchers want evidence to inform the public and decision makers about the impact of such policies in their future. We need multilevel evaluations that are integrated across sectors and strongly linked to trends in population health and well-being. While public health and epidemiologic researchers are used to undertaking such evaluations using large population-based registries, newer methods such as case studies and systems analysis should be adopted and refined for this purpose to augment what we are currently generating.70,71

The third type of evidence needed by policy makers and program planners concerns implementation of macro-social programs and policies. One macro-social policy that has received extensive support across North America is the Living Wage ordinance, which was first launched in the USA in the late 1980s and has spread to over 120 communities in the USA since that time.72 A living wage, which ranges between 50 and 250 % of the federal minimum wage depending on the geographic area, is meant to ensure that families have enough income to meet basic needs.72 Living wage ordinances across the USA usually require municipal service contractors, economic development recipients, and selected employers to pay wages and sometimes additional benefits to their employees. While limited in scope, numerous benefits to those receiving a living wage and to the community have been documented, with particular impact on the economic well-being of both employees and employers. Meanwhile, some anticipated negative impacts, such as massive job loss and excessive costs to municipalities, have not panned out. Perhaps because of their complexity and the myriad context-specific factors that shape the development and execution of each living wage ordinance, implementation has not been straightforward. Yet only in the last few years have experiences of multiple living wage cases been summarized and made available. These summaries include some mention of the challenges to and facilitators of successful implementation.73,74 But if initiatives with demonstrated benefits to poverty and inequalities are to grow, both in number and in scope, more information about implementation is needed. Outstanding questions remain about the best way to overcome some of the greatest challenges in implementation, including enforcement of policies, monitoring of compliance, reaching all employers covered by the mandate, and expanding the ordinance to cover a larger proportion of the local workforce. Furthermore, impacts beyond short-term improvements in economic well-being of living wage workers have yet to be documented. Until information and evidence is generated about how best to address these challenges and to improve their scope and mandates, living wage ordinances, for all their potential to significantly impact economic inequities, will remain small in scope and impact.72,75

Conclusions

Policy makers and program planners have noted a need for research on social determinants of health to shift from primarily describing associations with health to generating evidence to solve these problems. To generate such evidence, social epidemiologists and public health researchers could benefit from efforts to expand knowledge around macro-social impacts on health and population well-being. Research should not stop at demonstrating whether and how a program or policy improves well-being. More detailed information is also needed to facilitate adaptation, tailoring, and implementation of those programs and policies to local settings and target populations.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research under grant #101693, entitled “Power, Politics, and the Use of Health Equity Research.”

References

- 1.Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson R, Pickett K. Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szanton P. Not Well Advised: The City as Client—an Illuminating Analysis of Urban Governments and Their Consultants. San Jose: Authors Choice; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownson R, Royer C, Ewing R, McBride T. Researchers and policymakers: travelers in parallel universes. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi B, Gupta A, Ward B. Good thinking: six ways to bridge the gap between scientists and policy makers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:179–180. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Exworthy M. Policy to tackle the social determinants of health: using conceptual models to understand the policy process. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23:318–327. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansen M, van Oers H, Kok G, de Vries N. Public health: disconnections between policy, practice and research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8(37). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Murphy K, Fafard P. Knowledge translation and social epidemiology: taking power, politics, and values seriously. In: O’Campo P, Dunn J, editors. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Toward a Science of Change. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogilvie D, Craig P, Griffin S, Macintyre S, Wareham N. A translational framework for public health research. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(116). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Petticrew M. When are complex interventions ‘complex’? When are simple interventions ‘simple’? Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(4):397–398. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Macintyre S, Graham H, Egan M. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 1: the reality according to policymakers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:811–816. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best A, Hiatt R, Norman C. Knowledge integration: conceptualizing communications in cancer control systems. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(3):313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham I, Logan J, Harrison M, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2006;26:13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitton C, Adair C, McKenzie E, Patten S, Perry B, Adair E. Knowledge transfer and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. 2007;85(4):729–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alternative Federal Budget 2011: Rethink, Rebuild, Renew: A Post-Recession Recovery Plan. Ottawa: Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishel L, Shierholz H. Sustained, High Joblessness Causes Lasting Damage to Wages, Benefits, Income and Wealth. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Campo P, Dunn J, eds. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Toward a Science of Change. New York: Springer; 2011.

- 18.Cox J. US Housing Crisis Is Now Worse Than the Great Depression. www.cnbc.com; 2011.

- 19.Hough A. More middle class families ‘will become homeless’ due to recession. The Telegraph, 2011.

- 20.Rampell C. Length of unemployment continues to break records. The New York Times. August 5, 2011.

- 21.Shah A. Today, over 22,000 children died around the world. Global Issues: Social, Political, Economic and Environmental Issues That Affect Us All. Available at: http://www.globalissues.org/article/715/today-over-22000-children-died-around-the-world.

- 22.Fieldhouse A, Shapiro I. The Facts Support Raising Revenues from the Highest-Income Households. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute & The Century Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krugman P. The Hijacked Crisis. New York Times. August 11, 2011.

- 24.Stiglitz J. Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%. Vanity Fair; May 2011.

- 25.Yalnizyan A. The Rise of Canada’s Richest 1%. Ottawa: Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berkman LF. Seeing the forest and the trees: new visions in social epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:1–2. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.House JS. Understanding social factors and inequalities in health: 20th century progress and 21st century prospects. J Heal Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):125–142. doi: 10.2307/3090192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Putnam S, Galea S. Epidemiology and the macrosocial determinants of health. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29(3):275–289. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz SD, Carpenter KM. The right answer for the wrong question: consequences of type iii error for public health research. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bonneux L. From evidence based bioethics to evidence based social policies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:483–485. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9155-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S163–S175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muntaner C, Sridharan S, Chung H, et al. The solution space: developing research and policy agendas to eliminate employment-related health inequalities. Int J Heal Serv. 2010;40(2):309–314. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.2.j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong R, Doyle J, Lamb C, Waters E. Multi-sectoral health promotion and public health: the role of evidence. J Public Health. 2006;28(2):168–172. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ministerial Summit on Health Research. The Mexico statement on health research: knowledge for better health: strengthening health systems Available at: http://www.who.int/rpc/summit/agenda/Mexico_Statement-English.pdf

- 35.Whitehead M, Petticrew M, Graham H, Macintyre SJ, Bambra C, Egan M. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 2: assembling the evidence jigsaw. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(10):817–821. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.015297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenfield P. The potential for transdisciplinary research for sustaining and extending linkages between the health and social sciences. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35(11):1343–1357. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90038-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirst M, Schafer-McDaniel N, Hwang S, O’Campo P. Converging Disciplines: A Transdisciplinary Research Approach to Urban Health Problems. Berlin: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirst M, O’Campo P. Realist review methods for complex health problems. In: O’Campo P, Dunn J, editors. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Toward a Science of Change. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy K, Wolfus B, Lofters A. From complex problems to complex problem-solving: transdisciplinary practice as knowledge translation. In: Kirst M, Schafer-McDaniel N, Hwang S, O’Campo P, editors. Converging Disciplines: A Transdisciplinary Research Approach to Urban Health Problems. Berlin: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noonan E, Bjorndal A. The Campbell Collaboration. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/details/editorial/839335/The-Campbell-Collaboration.html. Accessed August 15, 2011.

- 41.Aronson R, Wallis AB, O’Campo P, Whitehead T, Schafer P. Ethnographically informed community evaluation: a framework and approach for evaluating community based initiatives. Matern Child Healt J. 2007;11(2):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKey R, Condelli L, Ganson H, Barrett B, McConkey C, Plantz M. The Impact of Head Start on Children, Families and Communities. Final Report of the Head Start Evaluation, Synthesis and Utilization Project. Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saari E, Kallio K. Developmental impact evaluation for facilitating learning in innovation networks. Am J Eval. 2011;32:227–245. doi: 10.1177/1098214010387658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen H-T. Theory-Driven Evaluations. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coryn C, Noakes L, Westine C, Schroter D. A systematic review of theory-drive evaluation practice from 1990–2009. Am J Eval. 2011;32(3):199–226. doi: 10.1177/1098214010389321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Protocol—realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards (RAMESES) BMC Med Res Methodology. 2011;11(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranmuthugala G, Cunningham FC, Plumb JJ, et al. A realist evaluation of the role of communities of practice in changing healthcare practice. Implementation Sci. 2011;6(49). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. Internet-based medical education: a realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances. BMC Med Education. 2010;10(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.O’Campo P, Kirst M, Schaefer-McDaniel N, Firestone M, Scott A, McShane K. Community-based services for homeless adults experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders: a realist approach to synthesizing evidence. J Urban Health. 2009;86(6):965–989. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Campo P, Kirst M, Tsamis C, Chambers C, Ahmad F. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Preventive Services US. Task force. Recommendation statement: screening for family and intimate partner violence. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):382–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gamble JAA. A Developmental Evaluation Primer. Montréal: JW McConnell Family Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patton MQ. Developmental evaluation. Eval Pract. 1994;15(3):311–319. doi: 10.1016/0886-1633(94)90026-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keller C, Goering P, Hume C, et al. Initial implementation of Housing First in five Canadian cities: how do you make the shoe fit, when one size does not fit all? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012; in press.

- 57.Macnaughton EGP, Nelson G. Using mixed methods within the At Home/Chez Soi Housing First project: a strategy to evaluate the implementation of a complex population health intervention for people with lived experience of homelessness and mental illness. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2012; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Devaney B, Howell E, McCormick M, Moreno L. Reducing Infant Mortality: Lessons Learned from Healthy Start. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherk J. How Congress Can Support, Not Hinder, Labor Market Recovery. Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Health Canada. Tobacco Control Programme, Health Canada Supplementary Tables, Youth Smoking Survey 2006–07. Table 4a. Smoking status by province, grades 5–9, Canada, 2006-07. 2008-12-22. Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/_survey-sondage_2006-2007/table-04-eng.php.

- 61.Brinn MP, Carson KV, Esterman AJ, Chang AB, Smith BJ. Mass media interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(11):CD001006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Carson KV, Brinn MP, Labiszewski NA, Esterman AJ, Chang AB, Smith BJ. Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;(7):CD001291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Lantz PM. Youth Smoking Prevention Policy: Lessons Learned and Continuing Challenges. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lovato C, Linn G, Stead LF, Best A. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(4):CD003439. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Priest N, Armstrong R, Doyle J, Waters E. Policy interventions implemented through sporting organisations for promoting healthy behaviour change. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD004809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions for preventing tobacco sales to minors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(1):CD001497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Thomas RE, Baker PRA, Lorenzetti D. Family-based programmes for preventing smoking by children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(1):CD004493. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.McCall L, Kenworthy L. Americans’ social policy preference in the era of rising inequality. Perspectives on Politics. 2009;7(3):459–484. doi: 10.1017/S1537592709990818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Russell E, Dufour M. Rising Profit Shares, Falling Wage Shares. Toronto: Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leischow S, Best A, Trochim W, et al. Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2S):S196–S203. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schulz A, Northridge M. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(3):455–471. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chapman J, Thompson J. The Economic Impact of Local Living Wages. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zabin C, Martin I. Living Wage Campaigns in the Economic Policy Arena: Four Case Studies from California. Berkeley: Center for Labor Research and Education, Institute of Industrial Relations, University of California; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luce S. The role of community involvement in living wage ordinances. Ind Relat. 2005;44(1):32–58. doi: 10.1111/j.0019-8676.2004.00372.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pollin R. Evaluating living wage laws in the United States: good intentions and economic reality in conflict? Econ Dev Q. 2005;19(1):3–24. doi: 10.1177/0891242404268641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oxman A, Lavis J, Lewin S, Fretheim A. SUPPORT tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 10: taking equity into consideration when assessing the findings of a systematic review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(Suppl 1):S10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]