Abstract

Background

Since the RpoN-RpoS regulatory network was revealed in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi a decade ago, both upstream and downstream of the pathway have been intensively investigated. While significant progress has been made into understanding of how the network is regulated, most notably, discovering a relationship of the network with Rrp2 and BosR, only three crucial virulence factors, including outer surface protein C (OspC) and decorin-binding proteins (Dbps) A and B, are associated with the pathway. Moreover, for more than 10 years no single RpoS-controlled gene has been found to be critical for infection, raising a question about whether additional RpoS-dependent virulence factors remain to be identified.

Methodology/Principal Findings

The rpoS gene was deleted in B. burgdorferi; resulting mutants were modified to constitutively express all the known virulence factors, OspC, DbpA and DbpB. This genetic modification was unable to restore the rpoS mutant with infectivity.

Conclusions/Significance

The inability to restore the rpoS mutant with infectivity by simultaneously over-expressing all the three virulence factors allows us to conclude RpoS also regulates essential genes that remain to be identified in B. burgdorferi.

Introduction

The Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi has three σ factors, including the major factor, RpoD (σ 70), and two alternative factors, RpoN (σ 54) and RpoS (σ 38). A pioneering study by Norgard and colleagues published in 2001 successfully associated the two alternative factors to form a regulatory network, in which RpoS expression depends on RpoN and controls expression of at least three important surface lipoproteins including outer surface protein C (OspC), and decorin-binding proteins (Dbps) A and B [1], This started the era of intensively investigating both up- and down-stream of the RpoN-RpoS pathway [2]. Yang et al. promptly added the response regulator Rrp2 to the pathway, in which Rrp2 controls the activity of RpoN, which in turn controls RpoS expression [3]. Recently Yang and colleagues further showed Rrp2 can simply be activated by acetyl-phosphate [4]. Another line of study by at least two independent groups showed BosR is essential for expression of RpoS [5]–[8]. A third line of investigation led by Samuels showed small RNA is also involved in regulation of RpoS [9]. These studies have significantly advanced understanding of how the RpoN-RpoS network is regulated but also highlight the complicated nature of the network.

In contrast to significant progress made towards understanding of the upstream regulation of the RpoN-RpoS pathway, very little information has been gained regarding virulence genes regulated by the pathway since initial identification of the network. Fisher et al. by using microarray analysis showed RpoN and RpoS can either independently regulate many genes or form an RpoN-RpoS regulatory cascade to regulate even more genes [10]. By using the same technique Radolf and colleagues identified 137 genes, whose expression is differentially regulated by RpoS [11]. While this screening technique was unable to expand knowledge on the spectrum of virulence genes controlled by RpoS, when careful studies focusing on an individual gene was conducted, several genes, including bba64, bb0844, bba07and bbk32 (fibronectin-binding protein gene have been confirmed to be RpoS-dependent [12]–[14] since the RpoN-RpoS pathway was discovered more than a decade ago [1]. Among these newly identified RpoS-regulated factors, only BBA07 and BBK32 were shown some roles in mammalian infection [13], [15]–[17].

No new crucial virulence factor controlled by RpoS has been identified after 10 years of intensive investigation, raising a question about whether the RpoN-RpoS pathway also regulates additional important genes. As deletion of the ospC gene alone abrogates infectivity, the essential role of RpoS in mammalian infection can be simply explained as its role in controlling OspC expression [18]. Moreover, lack of either DbpA or DbpB dramatically reduces infectivity, and deletion of both causes an accumulative effect [19]–[22]. To examine whether RpoS regulates essential genes that remain to be identified, the rpoS gene was first deleted. A resulting mutant was then modified to constitutively express ospC, dbpA and dbpB, and inoculated into mice. The inability to restore infectivity by simultaneously over-expressing the three crucial virulence factors indicated that other essential gene(s) controlled by the RpoN-RpoS pathway remains to be identified.

Materials and Methods

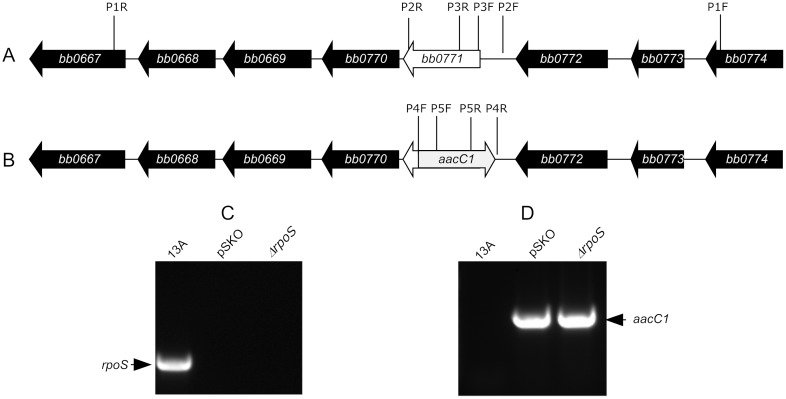

Construction of disruption plasmid pSKO

To delete the rpoS gene, a disruption plasmid, pSKO, was constructed. Briefly, a 6485-bp fragment with introduced Acc65I and NheI restriction sites at the ends, consisting of a partial sequence of the open-reading frame (ORF) bb0767, the entire ORFs for bb0768, bb0769, bb0770 bb0771 (rpoS), bb0772 and bb0773, and a part of the ORF bb0774, was PCR amplified using the primers P1F and P1R (Fig. 1A; Table 1). The resulting amplicon was digested with the restriction enzymes Acc65I and NheI, purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA), and cloned into the vector pNCO1T, as described previously [19], creating an intermediate construct, pNCO1TS. It was then used as a template to generate to a fragment with bb0771 deleted by using the primers P2F and P2R. A gentamicin cassette (aacC1) was amplified from the vector pBSV2G (a gift from P. Rosa and P. Stewart) with use of the primers P4F and P4R [23]. The two amplicons were pooled, purified, digested with BamHI and NcoI, and ligated to complete construction of pSKO.

Figure 1. Generation of rpoS mutant.

(A) Diagram of the rpoS locus (bb0771) and adjacent ORFs. The binding sites of six primers, i.e. P1F to P3F and P1R to P3R, are also indicated. (B) Diagram of the disrupted rpoS locus, showing a major portion of rpoS gene is replaced with the aacC1 cassette (grey arrow). The small arrow points a residual portion of rpoS. The binding sites of primers P4F, P5F, P5R and P4R are also indicated. (C&D) PCR analysis of rpoS mutant. The 13A spirochetes, the disruption plasmid pSKO, and ΔrpoS were used as DNA sources and subjected to PCR amplification using the primers P3F and P3R producing an amplicon of 111 bps (C), and the primers P5F and P5R generating an amplicon of 517 bps (D).

Table 1. Primers used in the study a.

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

| P1F | ATGGTACCAGGAAGTGAAGGCAT |

| P1R | ACGCTAGCAAGCTGGATGCAATA |

| P2F | AACCATGGCAAGGCCAAAGCTTTGAG |

| P2R | ACGGATCCAACAGAACTTGGAATATCATC |

| P3F | CAGTAAGAGAACACAAGCTAATTACT |

| P3R | GTCGCAAGTTTGCATTTATCATCT |

| P4F | AACAGGATCCTAGGTAATACCCGAGCTTC |

| P4R | AACCATGGTCTGACGCTCAGTGGAA |

| P5F | TCACGGTGTTATGGAAATAG |

| P5R | GACTGCGAGATCATAGATATAG |

| P6F | AAGGATCCTTGGAGGAAATTGATGGAA |

| P6R | CCTCTAGACCACTGACTTACAAGTAGAC |

| P7F | AAGGTACCAAGATAGAGAGAGAAAAGTG |

| P7R | TAGGATCCTTAAGGTTTTTTTGGACTTTCT |

| P8F | AAGGATCCTAAATTTAATAGAAGGAGGAA |

| P8R | AACTGCAGGTCTTGATTATCGGGCGAAGAG |

The underlined sequences are restriction enzyme sites: Acc65I sites (P1F and P7F), BamHI sites (P2R, P4F, P6F, P7R and P8F), NcoI sites (P2F and P4R), a NheI site (P1R), a PstI site (P8R), and an XbaI site (P6R).

Deletion of the rpoS locus

The B. burgdorferi B31 13A spirochetes were grown to late-logarithmic (log) phase in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly H (BSK-H) complete medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 33°C. The clone 13A was derived from a highly transformable clone, the B. burgdorferi B31 5A13, which harbors 20 plasmids but lacks lp25 [24]. Further loss of lp56 makes the clone 13A more transformable [25]. Approximately 10 µg of pSKO DNA was electroporated into the 13A spirochetes harvested from a 40-ml culture; resulting gentamicin-resistant clones were screened as described previously [19]. The plasmid content of resulting mutants was analyzed as previously described [26]. The replacement of rpoS with the aacC1 cassette was confirmed by PCR using the primers P3F and P3R unique for rpoS (Fig. 1A; Table 1), and P5F and P5R specific for the aacC1 cassette (Fig. 1B).

trans-Complementation of rpoS mutant and modification of the mutant to simultaneously express OspC, DbpA and DbpB

Two constructs were generated as illustrated in Fig. 2. Briefly, a 1329-bp sequence, containing the entire rpoS gene including the upstream, coding and downstream regions, was amplified with use of the primers P6F and P6R (Table 1), digested with BamHI and XbaI, purified, and cloned into the shuttle vector pBBE22 [27], after the vector was digested with the same enzymes, to complete construction of pBBE22-rpoS (Fig. 2A).

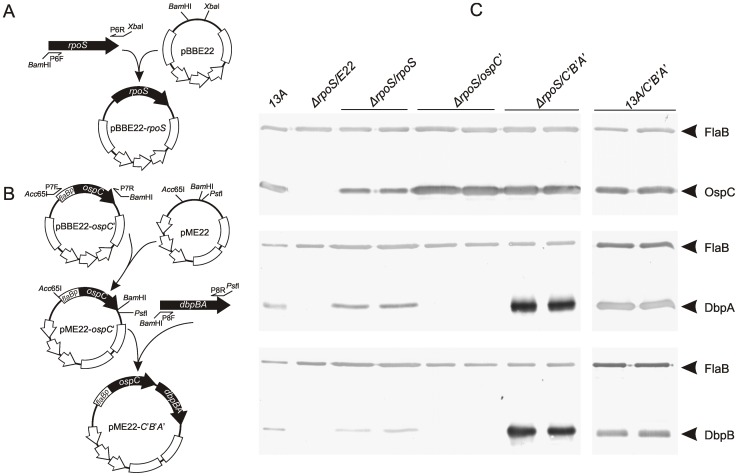

Figure 2. trans-Complementation of the rpoS mutant and modification of the mutant to constitutively express OspC and to simultaneously express OspC, DbpA and DbpB.

(A&B) Construction of pBBE22-rpoS and pME22-C′B′A′. All restriction enzyme sites and primer binding sites used for plasmid construction are labeled. (C) Confirmation of OspC, DbpA and DbpB production by immunoblotting. The parental clone 13A and transformants ΔrpoS/E22, ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/ospC′, ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ and 13A/C′B′A′ were grown to late-log phase in BSK-H complete medium, harvested by centrifugation and subjected to immunoblot analyses probed with a mixture of FlaB mAb and OspC mAb (top), or mouse anti-DbpA (middle) or -DbpB sera (bottom).

To construct pME22-C′B′A′, the fragment flaBp-ospC was amplified from pBBE22-ospC′ with use of the primers P7F and P7R, digested with Acc65I and BamHI, purified, and cloned into the shuttle vector pME22, to create pME22-ospC′ (Fig. 2B). pBBE22-ospC′ and pME22 were generated in our earlier studies [19], [28]. A 1418-bp promoterless dbpBA operon, including the entire dbpBA coding region, the space between the two gene, 25 bps of upstream sequence (from the dbpB start codon) and 218 bps of downstream sequence (from the dbpA stop codon), was amplified from borrelial DNA with use of the primer P8F and P8R, digested with BamHI and PstI, purified, and cloned into pME22-ospC′, to complete construction of pME22-C′B′A′ (Fig. 2B). All inserts were sequenced to ensure that the inserts and their flanking sequences were as designed.

Four constructs, pBBE22, pBBE22-rpoS, pBBE22-ospC′ and pME22-C′B′A′, were electroporated into the rpoS mutant; resulting transformants were identified as previously described [25]. pME22-C′B′A′ was also electroporated into the parental clone 13A as a control. Plasmid analyses were performed as described in our earlier study [26]. Restoration of OspC, DbpA and DbpB expression due to introduction of pBBE22-rpoS, overexpression of OspC due to introduction of pBBE22-ospC′, and simultaneous overexpression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB due to introduction of pME22-C′B′A′ were confirmed by immunoblot analyses, performed as described in our earlier studies [19], [25].

Growth rate estimation

B. burgdorferi was grown at 33°C to late log phase (approximately 108 cells/ml) in BSK-H medium, and then diluted to 105 cells/ml with the medium. Cell numbers were determined once a day for 10 days under dark-field microscopy.

Adaptation of B. burgdorferi in host-adapted mammalian environment

Host-adapted spirochetes were prepared in a dialysis membrane chamber (DMC) as described by Akins et al [29]. The Spectra/Por® 6 Standard Grade Regenerated Cellulose dialysis membrane with molecular weight cut-off of 8 kDa (Spectrum Laboratories Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA) was treated with 5 mM EDTA and then autoclaved. Using the standard aseptic surgical procedure, a sterilized DMC was filled with 5 ml of 103 spirochetes per ml suspended in complete BSK-H medium, and implanted into the peritonea of a Sprague-Dawley rat (6–8 weeks old; Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine at Louisiana State University, Baton rouge, LA). The DMC was harvested at different time points ranging from 2 to 10 weeks. All animal procedures described here and below were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Louisiana State University.

Infection study

Severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice on a BALB/c background (age, 4 to 6 weeks; provided by the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA) each received one single intradermal/subcutaneous injection of 105 spirochetes. Inoculated animals were euthanized 1 month post-inoculation; heart, tibiotarsal joint and skin specimens were aseptically collected for spirochete culture as described previously [26].

Estimation of tissue spirochetal load

Heart, joint, and skin specimens were harvested from infected mice and extracted for DNA. DNA was quantified for the copy numbers of flaB and murine actin genes by quantitative PCR (qPCR) as described previously [26]. The tissue spirochete burden was expressed as flaB DNA copies per 106 host cells (2×106 actin DNA copies).

Quick clearance study

BALB/c SCID mice were given two intradermal/subcutaneous injections of 105 spirochetes. The two inoculation sites were at least 2 cm apart. Animals were sacrificed 24 and 48 hours later; inoculation site skin tissues were harvested for spirochete isolation as described previously [26].

Results and Discussion

Generation of rpoS mutant

Thirteen gentamicin-resistant clones were obtained from electroporation of pSKO into the 13A spirochetes. Plasmid content analyses led to selection of one clone, namely, ΔrpoS, which had lost cp9, lp5 and lp21, in addition to lp25 and lp56. The replacement of rpoS with the aacC1 cassette was confirmed by PCR using the primers unique for rpoS (Figure 1C), and P5F and P5R specific for the aacC1 cassette (Figure 1D).

trans-Complementation of the rpoS mutant and modification of the mutant to simultaneously produce OspC, DbpA and DbpB

Because the parental clone 13A and ΔrpoS lost lp25, the plasmid that carries the gene bbe22 coding for a nicotinamidase essential for survival of B. burgdorferi in the mammalian environment, the recombinant plasmids pBBE22 and pME22, which harbor a copy of bbe22, were used as shuttle vectors [19], [27]. pME22 was modified from pBBE22 by replacing the restriction enzyme site XbaI with two sites, Acc65I and PstI. This modification made it easy to insert a large insert into the vector. The features of the constructs are summarized in Table 2. pBBE22-rpoS and pME22-C′B′A′ were generated as illustrated in Figure 2. pBBE22-rpoS was constructed by cloning the full-length rpoS gene into pBBE22. pME22-C′B′A′ was created by first cloning a promoterless ospC gene fused with the flaB promoter into pME22 from pBBE22-ospC′, followed by inserting a promoterless dbpBA gene. This construct was designed in this way in order to use a single flaB promoter to drive constitutive OspC, DbpA and DbpB expression. pBBE22-ospC′ were constructed in an earlier study [27], [28].

Table 2. Constructs and clones used in the study.

| Construct or clone | Description | Source |

| pBBE22 | pBSV2 carrying a bbe22 copy | Reference [27] |

| pME22a | pBSV2 carrying a bbe22 copy | Reference [19] |

| pBBE22-ospC′ | pBBE22 carrying promoterless ospC fused with flaB promoter | Reference [28] |

| pME22-C′B′A′ | pME22 carrying promoterless ospC, dbpB and dbpA fused with flaB promoter | This study |

| 13A | Cloned from the B. burgdorferi B31 5A13 | Reference [25] |

| ΔrpoS | rpoS mutant | This study |

| ΔrpoS/rpoS | ΔrpoS receiving pBBE22 carrying a wild-type rpoS copy | This study |

| ΔrpoS/E22 | ΔrpoS receiving pBBE22 | This study |

| ΔrpoS/ospC′ | ΔrpoS expressing ospC driven by flaB promoter | This study |

| ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ | ΔrpoS expressing ospC, dbpB and dbpA driven by flaB promoter | This study |

pME22 was modified from pBBE22 by removing the bbe22 copy from the Acc65I site to the AatII in order to make the Acc65I site available for cloning [19].

The four constructs were electroporated into ΔrpoS. pME22-C′B′A′ was also introduced into the parental clone 13A. Between 13 and 23 transformants were obtained from transformation with each construct. Plasmid analyses led to identification of one or two clones receiving each construct. These nine clones had the same plasmid content as ΔrpoS, which lost cp9, lp5, lp21, lp25 and lp56. Restoration of OspC, DbpA and DbpB expression resulting from transformation was confirmed by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 2C, the clone ΔrpoS/E22 didn't express any of the three surface lipoproteins as it received the empty plasmid pBBE22. As expected, transformation with the construct pBBE22-rpoS restored the ΔrpoS mutant with production of all the three lipoproteins. As the function of pBBE22-ospC′ to drive OspC expression was already confirmed in our previous study [28], introduction of this construct, also as expected, resulted in abundant OspC production. This was the first time a single promoter was used to drive expression of three fused genes in B. burgdorferi. As designed, pME22-C′B′A′ did successfully confer the ΔrpoS mutant with constitutive production of OspC, DbpA and DbpB (Figure 2C). As a control, pME22-C′B′A′ was introduced into 13A. Although the parental strain contained the normal rpoS gene, whose product was expected to drive active production of the three as well as other RpoS-dependent lipoproteins, introduction of the construct did result in high levels of OspC, DbpA and DbpB production as it did in the rpoS mutant, probably because of the space limitation on the spirochetal surface where the three antigens have to share with other lipoproteins.

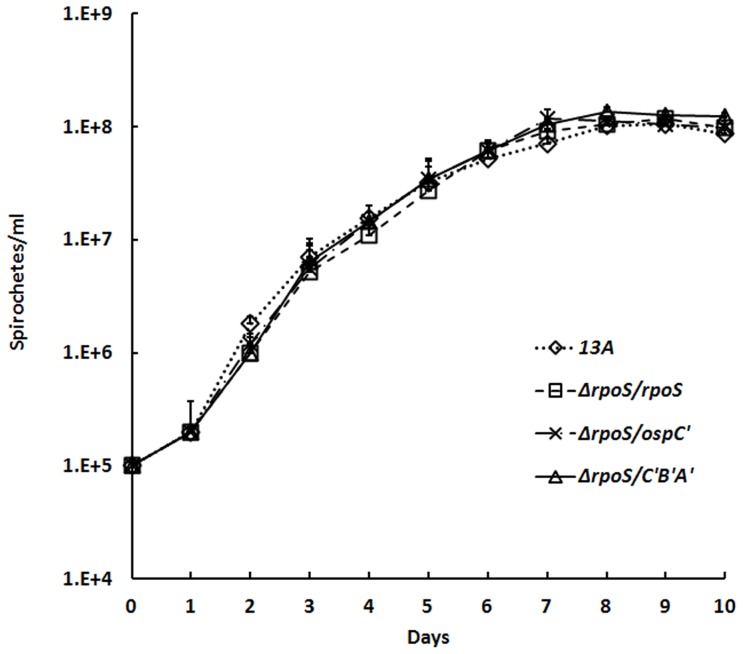

Simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB doesn't alter in vitro growth

We didn't notice any growth defects of the transformants during selection processes. Nevertheless, to rule out any possibility of growth defects resulting from modification of simultaneously constitutive expression of the lipoproteins, we carefully examined in vitro growth rates. As shown in Figure 3, all the three examined transformants, ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/ospC′ and ΔrpoS/C′B′A′, produced similar growth curves as the parental clone 13A.

Figure 3. Modification of the rpoS mutant to constitutively produce surface lipoproteins doesn't alter its growth rate.

The parental clone 13A and transformants ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/ospC′ and ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ were cultured in BSK-H at 33°C. Cell numbers were determined once a day for 10 days under dark-field microscopy.

Simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB fails to restore the rpoS mutant with infectivity

To examine if abundant production of the three critical virulence factors is able to overcome the absence of RpoS, groups of six SCID mice were inoculated with a single intradermal/subcutaneous dose of 105 organisms of the clone ΔrpoS/E22, ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/ospC′, ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ and 13A/C′B′A′. Immunodeficient mice were used because constitutive expression of the three surface lipoproteins or even OspC alone may lead to clearance by specific antibodies induced during infection of immunocompetent mice [28]. Mice were sacrificed 1 month post-inoculation; heart, tibiotarsal joint and skin specimens were harvested for spirochete culture. All of the six mice that received ΔrpoS/rpoS were infected, demonstrating that the ΔrpoS was fully competent via complementation with a wild-type rpoS gene (Table 3). In contrast, none of the six mice that were inoculated with the clone ΔrpoS/E22 produced a positive tissue, a result that is consistent with previous studies showing that RpoS is essential for mammalian infection. None of the 12 mice that were challenged with the clone ΔrpoS/ospC′ or ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ produced a positive culture, indicating that either constitutive production of OspC or simultaneously abundant expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB is unable to override the requirement for RpoS in murine infection.

Table 3. Simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB was unable to restore the rpoS mutant with infectivity a.

| No. of cultures positive/total specimens examined | No. of mice infected/total mice inoculated | ||||

| Clone | Heart | Joint | Skin | All sites | |

| ΔrpoS/rpoS | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 18/18 | 6/6 |

| ΔrpoS/E22 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/18 | 0/6 |

| ΔrpoS/ospC′ | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/18 | 0/6 |

| ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/18 | 0/6 |

| 13A/C′B′A′ | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 18/18 | 6/6 |

Groups of six SCID mice were inoculated with 105 organisms of the transformant ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/E22, ΔrpoS/ospC′, ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ or 13A/C′B′A′ and sacrificed 1 month later. Heart, tibiotarsal joint and skin specimens were harvested for spirochete culture.

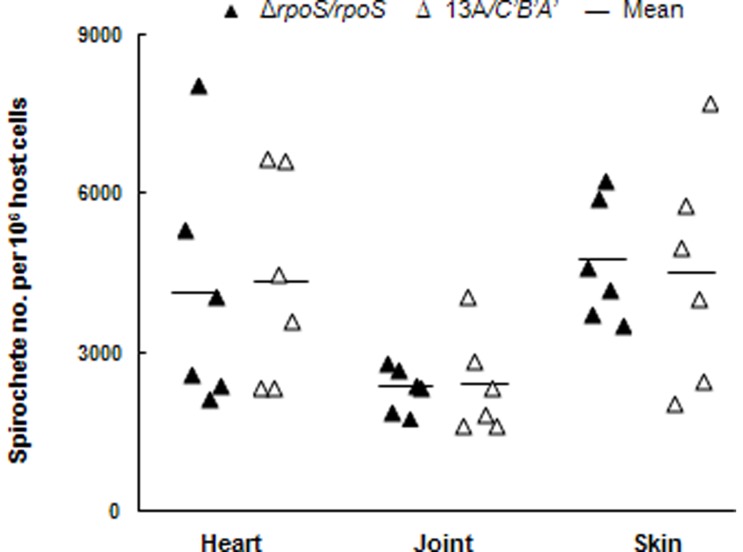

All the mice that received 13A/C′B′A′ produced culture-positive tissues. DNA samples were prepared from the heart, joint and skin specimens of infected mice and analyzed for tissue bacterial loads. As shown in Figure 4, simultaneously constitutive expression of the three lipoproteins didn't significantly alter tissue colonization of the parental spirochetes. To rule out the possibility that mutants might have been selected, spirochetes were isolated from mice that were inoculated with the transformant 13A/C′B′A′ and further characterized. PCR amplification confirmed the presence of the introduced construct pME22-C′B′A′ and immunoblotting showed high levels of OspC, DbpA and DbpB expression (data not shown), demonstrating that pME22-C′B′A′ was well maintained during murine infection.

Figure 4. Simultaneously constitutive expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB doesn't significantly alter tissue colonization in SCID mice.

Groups of six BALB/c SCID mice were infected either with transformant ΔrpoS/rpoS or 13A/C′B′A′ for 1 month. DNA samples were prepared from the heart, joint and skin specimens and analyzed for spirochete flaB and murine actin DNA copies by qPCR. The data are expressed as spirochete numbers per 106 host cells.

Simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB is unable to protect the rpoS mutant from quick clearance

A previous study showed increasing production of DbpA driven by the flaB promoter reduces the ID50 but severely impairs dissemination, probably because the modification enhances the interaction of the pathogen with host decorin [30]. This led us to speculate that increased production of the lipoproteins, especially DbpA and DbpB, may impair dissemination and restrict spirochetes at the inoculation site. To rule out this possibility, groups of six SCID mice were given two intradermal/subcutaneous injections of 105 spirochetes of the clone ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/ospC′ and ΔrpoS/C′B′A′. Animals were euthanized at 24 or 48 hours later; inoculation site skin specimens were harvested for spirochete culture. As a positive control, the ΔrpoS/rpoS bacteria were consistently grown from all of the 12 inoculation sites harvested at 24 and 48 hours post-inoculation (Table 4). In contrast, none of the 24 sites from the 12 remaining mice produced a positive culture, indicating quick clearance of bacteria from the inoculation site.

Table 4. Simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB was unable to protect the rpoS mutant from quick clearance a.

| Clone | No. of sites positive/Total no. of sites examined at post-inoculation hours | |

| 24 hours | 48 hours | |

| ΔrpoS/rpoS | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| ΔrpoS/E22 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| ΔrpoS/ospC′ | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ | 0/6 | 0/6 |

Groups of six SCID mice each received two intradermal/subcutaneous injections of the transformant ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/E22, ΔrpoS/ospC′ or ΔrpoS/C′B′A′. Approximately 105 organisms were administered in each inoculation; two inoculation sites were at least 2 cm apart. Three animals from each group were euthanized at 24 and 48 hour post-inoculation; skin specimens were harvested from inoculation sites and cultured for spirochetes in BSK-H complete medium.

The remaining concern, albeit minor, was whether quick clearance of bacteria resulted from longtime, intensive genetic manipulation of B. burgdorferi, a process that potentially attenuates the pathogen. To rule out this possibility, the transformants ΔrpoS/rpoS, ΔrpoS/ospC′ and ΔrpoS/C′B′A′ were first grown in DMC for 2, 4 and 10 weeks. The purpose to add this treatment was not to alter OspC, DbpA and DbpB expression levels, but to give spirochetes time to adapt to the mammalian environment. Resulting host-adapted B. burgdorferi was inoculated into the skin of SCID mice. Animals were euthanized at 24 or 48 hours later; inoculation site skin specimens were harvested for spirochete culture. As a positive control, the ΔrpoS/rpoS bacteria were consistently grown from all of the 12 inoculation sites harvested at 24 and 48 hours post-inoculation (data not shown). In contrast, none of the 24 sites from the remaining 12 mice produced a positive culture. The study allowed us to conclude that simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB is unable to protect the rpoS mutant from quick clearance in murine skin.

Ten plus years of intensive investigation resulted in no additional critical RpoS-dependent virulence genes to be found, leading to a speculation whether the regulatory network regulates unknown essential virulence factors. Simultaneous expression of OspC, DbpA and DbpB is unable to restore the rpoS mutant with infectivity or to protect from quick clearance. Our study clearly demonstrates that RpoS controls essential virulence factors that remain to be identified.

Funding Statement

This work was in part supported by RO1 AI077733 from the National Institutes of Health. No additional external funding received for this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hubner A, Yang X, Nolen DM, Popova TG, Cabello FC, et al. (2001) Expression of Borrelia burgdorferi OspC and DbpA is controlled by a RpoN-RpoS regulatory pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 12724–12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Samuels DS (2011) Gene regulation in Borrelia burgdorferi . Annu Rev Microbiol 65: 479–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang XF, Alani SM, Norgard MV (2003) The response regulator Rrp2 is essential for the expression of major membrane lipoproteins in Borrelia burgdorferi . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 11001–11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu H, Caimano MJ, Lin T, He M, Radolf JD, et al. Role of acetyl-phosphate in activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway in Borrelia burgdorferi . PLoS Pathog 6: e1001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. He M, Ouyang Z, Troxell B, Xu H, Moh A, et al. (2011) Cyclic di-GMP is essential for the survival of the Lyme disease spirochete in ticks. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ouyang Z, Kumar M, Kariu T, Haq S, Goldberg M, et al. (2009) BosR (BB0647) governs virulence expression in Borrelia burgdorferi . Mol Microbiol 74: 1331–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Samuels DS, Radolf JD (2009) Who is the BosR around here anyway? Mol Microbiol 74: 1295–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hyde JA, Shaw DK, Smith Iii R, Trzeciakowski JP, Skare JT (2009) The BosR regulatory protein of Borrelia burgdorferi interfaces with the RpoS regulatory pathway and modulates both the oxidative stress response and pathogenic properties of the Lyme disease spirochete. Mol Microbiol 74: 1344–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lybecker MC, Samuels DS (2007) Temperature-induced regulation of RpoS by a small RNA in Borrelia burgdorferi . Mol Microbiol 64: 1075–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher MA, Grimm D, Henion AK, Elias AF, Stewart PE, et al. (2005) Borrelia burgdorferi sigma 54 is required for mammalian infection and vector transmission but not for tick colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 5162–5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caimano MJ, Iyer R, Eggers CH, Gonzalez C, Morton EA, et al. (2007) Analysis of the RpoS regulon in Borrelia burgdorferi in response to mammalian host signals provides insight into RpoS function during the enzootic cycle. Mol Microbiol 65: 1193–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banik S, Terekhova D, Iyer R, Pappas CJ, Caimano MJ, et al. BB0844, an RpoS-regulated protein, is dispensable for Borrelia burgdorferi infectivity and maintenance in the mouse-tick infectious cycle. Infect Immun 79: 1208–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu H, He M, He JJ, Yang XF Role of the surface lipoprotein BBA07 in the enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi . Infect Immun 78: 2910–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gautam A, Hathaway M, McClain N, Ramesh G, Ramamoorthy R (2008) Analysis of the determinants of bba64 (P35) gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi using a GFP reporter. Microbiology 154: 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seshu J, Esteve-Gassent MD, Labandeira-Rey M, Kim JH, Trzeciakowski JP, et al. (2006) Inactivation of the fibronectin-binding adhesin gene bbk32 significantly attenuates the infectivity potential of Borrelia burgdorferi . Mol Microbiol 59: 1591–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li X, Liu X, Beck DS, Kantor FS, Fikrig E (2006) Borrelia burgdorferi lacking BBK32, a fibronectin-binding protein, retains full pathogenicity. Infect Immun 74: 3305–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hyde JA, Weening EH, Chang M, Trzeciakowski JP, Hook M, et al. Bioluminescent imaging of Borrelia burgdorferi in vivo demonstrates that the fibronectin-binding protein BBK32 is required for optimal infectivity. Mol Microbiol 82: 99–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grimm D, Tilly K, Byram R, Stewart PE, Krum JG, et al. (2004) Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 3142–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shi Y, Xu Q, McShan K, Liang FT (2008) Both decorin-binding proteins A and B are critical for the overall virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi . Infect Immun 76: 1239–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shi Y, Xu Q, Seemanapalli SV, McShan K, Liang FT (2006) The dbpBA locus of Borrelia burgdorferi is not essential for infection of mice. Infect Immun 74: 6509–6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blevins JS, Hagman KE, Norgard MV (2008) Assessment of decorin-binding protein A to the infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine models of needle and tick infection. BMC Microbiol 8: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weening EH, Parveen N, Trzeciakowski JP, Leong JM, Hook M, et al. (2008) Borrelia burgdorferi lacking DbpBA exhibits an early survival defect during experimental infection. Infect Immun 76: 5694–5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elias AF, Bono JL, Kupko JJ 3rd, Stewart PE, Krum JG, et al. (2003) New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi . J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 6: 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Purser JE, Norris SJ (2000) Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 13865–13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu Q, McShan K, Liang FT (2007) Identification of an ospC operator critical for immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 64: 220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu Q, Seemanapalli SV, Lomax L, McShan K, Li X, et al. (2005) Association of linear plasmid 28-1 with an arthritic phenotype of Borrelia burgdorferi . Infect Immun 73: 7208–7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Purser JE, Lawrenz MB, Caimano MJ, Howell JK, Radolf JD, et al. (2003) A plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase (PncA) is essential for infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a mammalian host. Mol Microbiol 48: 753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu Q, Seemanapalli SV, McShan K, Liang FT (2006) Constitutive expression of outer surface protein C diminishes the ability of Borrelia burgdorferi to evade specific humoral immunity. Infect Immun 74: 5177–5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akins DR, Bourell KW, Caimano MJ, Norgard MV, Radolf JD (1998) A new animal model for studying Lyme disease spirochetes in a mammalian host-adapted state. J Clin Invest 101: 2240–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu Q, Seemanaplli SV, McShan K, Liang FT (2007) Increasing the interaction of Borrelia burgdorferi with decorin significantly reduces the 50 percent infectious dose and severely impairs dissemination. Infect Immun 75: 4272–4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]