Abstract

In Mexico mycetomas are mostly produced by Nocardia brasiliensis, which can be isolated from about 86% of cases. In the present work, we determined the sensitivities of 30 N. brasiliensis strains isolated from patients with mycetoma to several groups of antimicrobials. As a first screening step we carried out disk diffusion assays with 44 antimicrobials, including aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, penicillins, quinolones, macrolides, and some others. In these assays we observed that some antimicrobials have an effect on more than 66% of the strains: linezolid, amikacin, gentamicin, isepamicin, netilmicin, tobramycin, minocycline, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin-tazobactam, nitroxolin, and spiramycin. Drug activity was confirmed quantitatively by the broth microdilution method. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, linezolid, and amikacin, which have been used to treat patients, were tested in an experimental model of mycetoma in BALB/c mice in order to validate the in vitro results. Linezolid showed the highest activity in vivo, followed by the combination amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and amikacin.

Mycetoma is an important cause of dermatological consultation in many tropical and subtropical countries (17). Therapy for mycetoma caused by Nocardia brasiliensis has traditionally been based on the use of sulfonamides, such as dapsone, DDS, sulfamethoxypyridazine, and sulfadoxine (10, 11, 15, 16, 37). Streptomycin in combination with dapsone or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) has also been used to treat patients with actinomycetomas, particularly those cases produced by Streptomyces somaliensis (19), with a cure rate of about 63.2%. More recently, the use of SXT for the treatment of actinomycetoma has been reported (18, 25, 36). In our dermatology clinic we have used the combination amikacin-SXT to treat severe cases of mycetoma or those cases involving subjacent organs and have obtained a cure rate of about 95% (36; O. Welsh, and L. Vera-Cabrera, Abstr. 15th Cong. Int. Soc. Hum. Anim. Mycol., abstr. 354, 2003). However, in many cases the use of these drugs may run the risk of development of bacterial resistance or side effects (21, 37); therefore, it is important to assay other drugs in order to select more potent, less toxic antimicrobials.

Considering this background, we have begun to evaluate in vitro and with an experimental murine model the activities of alternative antimicrobials for the treatment of actinomycetoma caused by N. brasiliensis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms

In this work, we used 30 strains of N. brasiliensis isolated from patients with mycetoma referred to our clinical dermatology department. Since a subtaxon of N. brasiliensis, N. pseudobrasiliensis, has recently been described, we took care to include only N. brasiliensis sensu stricto strains in this study. The strains were identified by conventional biochemical tests (22), and their identities were confirmed by DNA sequencing of a region located between nucleotides 70 and 334 of the N. brasiliensis 16S RNA gene (GenBank accession number Z36935). This fragment was amplified with primers NOC-3 (5′-ACG GGT GAG TAA CAC GTG-3′) and NOC-4 (5′-AGT CTG GGC CGT GTC TCA GTC-3′), which are specific for sequences located in conserved areas, although DNA sequencing of some internal regions allowed us to differentiate most of the Nocardia species.

The strains were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar for 7 to 10 days, and a suspension of each strain was made in 20% skim milk. These bacterial suspensions constituted our stock cultures, which were kept at −70°C in cryovials until use.

Disk diffusion method

The N. brasiliensis strains were grown on Sabouraud agar for 7 days at 30°C, and several colony fragments were transferred to a sterile test tube. The bacterial mass was ground with a glass stick, and approximately 2 ml of saline solution was then added. The suspension was centrifuged at 100 × g for 10 min; and the turbidity of the supernatant, which mainly contained short fragments and nocardial cells, was adjusted to that of the 0.5 McFarland standard. One milliliter of this suspension was added to a 150-mm petri dish with Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% blood agar. After the plate surface was dry, paper disks containing the antimicrobials were placed on it, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. The inhibition zone diameters were measured at the end of this incubation period. Fine growth or haze was ignored when the readings were made. The interpretation was based on the NCCLS guidelines for gram-positive organisms, since there are no approved NCCLS guidelines for Nocardia. The following antimicrobials were used in this study: amikacin (30 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (20/10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), carbenicillin (100 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), imipenem (10 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), netilmicin (30 μg), ticarcillin-clavulanate (75/10 μg), SXT (1.25/23.75 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), and tetracycline (30 μg) were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Cockeysville, Md.). Aztreonam (30 μg), cefamandole (30 μg), cefotiam (30 μg), cefpirome (30 μg), cefsulodin (30 μg), ceftiofur (30 μg), enoxacin (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), isepamicin (30 μg), kanamycin (30 μg), moxalactam (30 μg), amdinocillin (10 μg), minocycline (30 μg), nitroxolin (20 μg), ofloxacin (10 μg), oxolinic acid (10 μg), pefloxacin (5 μg), pipemidic acid (20 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 μg), pristinamycin (15 μg), spectinomycin (100 μg), spiramycin (100 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), teicoplanin (30 μg), tobramycin (10 μg), and virginiamycin (15 μg) were obtained from Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur (Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Levofloxacin (5 μg) and cefepime (30 μg) disks were obtained from Productos Biológicos de México, S.A. (Mexico City, Mexico). Linezolid was kindly donated by Pharmacia Upjohn (Kalamazoo, Mich.), and disks containing 30 μg of the drug were prepared in-house.

Broth microdilution method

Amikacin, amoxicillin, gentamicin, netilmicin, spiramycin, trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, tobramycin, carbenicillin, minocycline, and nitroxolin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Products (St. Louis, Mo.). Isepamicin was obtained from Schering-Plough (Mexico City, Mexico). Premade amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (2:1; Augmentin) plates for MIC determinations were obtained from Dade Microscan (West Sacramento, Calif.). The linezolid MICs for the N. brasiliensis isolates included in this study have been reported elsewhere and therefore were not determined in the present work (30).

The broth microdilution method that we used has been described before (6, 7, 30). Briefly, we used fresh colonies on Sabouraud agar (7 days old) to prepare the inoculum. The bacterial suspension was diluted to obtain a solution with a final concentration of 1 × 104 to 5 × 104 CFU per well in 0.1 ml. This solution was added to microplate wells (Microtest Primaria; Becton Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, N.J.) containing an equal volume of broth and serial dilutions of the drugs to be tested. As a growth control we inoculated in the same way a well containing cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth without drug. After 3 days of incubation at 35°C, the plates were read and the MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of drug that totally inhibited nocardial growth. For the sulfonamides we considered the MIC to be the lowest concentration that inhibited 80% of the growth compared with the growth in the control well. We used Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 as external controls. All the antimicrobials except SXT were tested at concentrations of 0.25 to 64 μg/ml. The combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (which were used at a ratio of 1:20) was tested at concentrations ranging from 0.3/0.015 to 152/8 μg/ml.

Combination assays

We used a previously described (8) checkerboard method to determine the effects of the combinations of two drugs on N. brasiliensis,. Briefly, the drugs to be tested were diluted twofold from column 1 to column 10 of each microplate well. Twofold dilutions of drug B were then added to rows 1 to 8 and the wells were inoculated with 10 μl of the inoculum (1 × 104 to 5 × 104 CFU per well). The plates were incubated at 35°C for 3 days. In order to better visualize the presence of growth, Alamar blue was added to the plates. The fractional inhibitory concentrations of each combination were then calculated.

Experimental therapy for mycetoma caused by N. brasiliensis in BALB/c mice

Experimental mycetoma was produced by injecting 20 mg (wet weight) of a N. brasiliensis suspension into the left hind footpad of female BALB/c mice (age, 6 to 8 weeks) (12). The mice were divided into groups of 15 animals each, and 1 week later, the drugs were administered subcutaneously at a dose of 25 mg/kg of body weight twice a day for 4 weeks. A control group of animals was inoculated with saline solution.

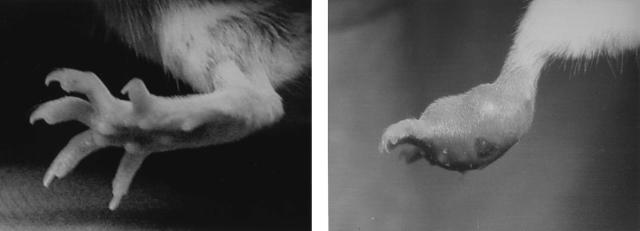

Ninety days after inoculation the mycetoma lesions were scored from 0 to 4+, depending on the level of development of the mycetoma lesions, from the presence of minimal or no inflammation to the extensive formation of abscesses, respectively (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Production of mycetoma lesions in infected BALB/c mice after 90 days of inoculation. Left photo, a mouse with no lesions; right photo, a mouse with a 4+ lesion.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was applied to determine significant differences among the experimental groups.

RESULTS

Disk diffusion method

A total of 44 antimicrobials belonging to different chemical groups were tested (Table 1). All aminoglycosides with the exception of kanamycin and streptomycin were active against 100% of the strains; kanamycin and streptomycin were active against less than 5% of the strains. Minocycline was also very active (93%), while tetracycline showed a low level of activity (38%). Beta-lactams did not show good activities against the N. brasiliensis strains unless they were combined with beta-lactamase inhibitors, in which case a significant increase in activity was observed, particularly when the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid was used. As expected, SXT was active against most of the strains. Two other compounds, nitroxolin and spiramycin, were active against more than 60% of the strains. Antimicrobials in the cephalosporin, macrolide, carbapenem, and quinolone groups had no activity or only low levels of activity against the N. brasiliensis strains tested.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of the N. brasiliensis strains to several antimicrobials determined by disk diffusion assays

| Antimicrobial | % Susceptible |

|---|---|

| More active drugs | |

| Aminoglycosides | |

| Amikacin | 100 |

| Gentamicin | 100 |

| Isepamicin | 100 |

| Netilmicin | 100 |

| Tobramycin | 100 |

| Tetracyclines (minocycline) | 93 |

| Beta-lactams | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 97 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 72 |

| Ticarcillin-Clavulanate | 45 |

| Quinolins (nitroxolin) | 72 |

| Sulfonamides (SXT) | 83 |

| Oxazolidinones (linezolid) | 100 |

| Less active drugs | |

| Aminoglycosides2 | |

| Streptomycin | 3 |

| Kanamycin | 0 |

| Aminocyclitols (spectinomycin) | 10 |

| Penicillins | |

| Ampicillin | 0 |

| Carbenicillin | 3.4 |

| Mecillinam | 0 |

| Cephalosporins | |

| Cefotaxim | 28 |

| Ceftiofur | 21 |

| Cefpirome | 17 |

| Cefepime | 17 |

| Ceftriaxone | 10 |

| Cefamandole | 3.4 |

| Cefotiam | 3.4 |

| Ceftazidime | 0 |

| Cefsulodin | 0 |

| Latamoxef | 10 |

| Glycopeptides (teicoplanin) | 3 |

| Macrolides | |

| Spiramycin | 66 |

| Erythromycin | 0 |

| Carbapenems | |

| Imipenem | 10 |

| Aztreonam | 0 |

| Quinolones | |

| Levofloxacin | 48 |

| Ofloxacin | 21 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 17 |

| Enoxacin | 0 |

| Pefloxacin | 0 |

| Streptogramins | |

| Virginiamycin | 0 |

| Pristinamycin | 0 |

Linezolid is known to be highly active against N. brasiliensis (7, 30). We included this drug in the disk diffusion assays because the inhibition zone diameters achieved with this drug have not yet been reported. All the strains tested were sensitive to linezolid (MIC at which 90% of strains tested are inhibited [MIC90], 2 μg/ml; MIC50, 1 μg/ml) (30) and showed large inhibition zone diameters (range, 30 to 42 mm; mean ± standard deviation, 37 mm).

Broth microdilution method

Antimicrobials with activities against more than 60% of the strains tested were assayed by the broth microdilution method (Table 2). The MICs of amikacin, gentamicin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and SXT were under the breakpoints established for Nocardia spp. for all the N. brasiliensis strains tested (6, 24). Although the breakpoints for isepamicin and netilmicin for Nocardia have not yet been established, the MICs of the two drugs for the N. brasiliensis strains were under the breakpoint for amikacin and the strains can probably be considered sensitive to the two drugs. Nitroxolin and spiramycin also showed good activities against the clinical isolates.

TABLE 2.

Activities of antimicrobial agents against clinical isolates of N. brasiliensis determined by the broth microdilution method

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |

| Amikacin | 0.125-4 | 2 | 4 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 1-32 | 2 | 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25->64 | 16 | 64 |

| Gentamicin | 0.125-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Isepamicin | 0.125-4 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Minocycline | 0.125-32 | 1 | 8 |

| Netilmicin | 0.25-4 | 4 | 4 |

| Nitroxolin | 1-16 | 4 | 4 |

| Spiramycin | 0.25->64 | 2 | 64 |

| SXT | 1.15/0.62 | 9.5/0.5 | 9.5/0.5 |

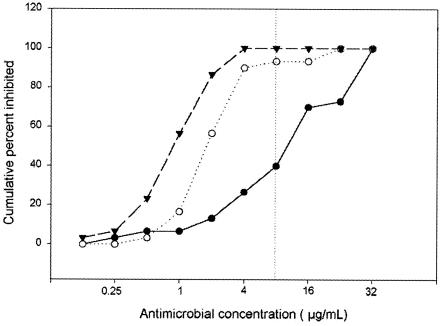

In our study most of the strains were resistant to ceftriaxone in the disk diffusion assays; however, since other investigators have published data supporting the sensitivity of N. brasiliensis to this cephalosporin (6, 7, 33), we included this drug in the broth microdilution assays. The cumulative MICs of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, amikacin, and ceftriaxone for the N. brasiliensis isolates are presented in Fig. 2. When a breakpoint of 8 μg/ml for the three antimicrobials was considered (24), ceftriaxone was the least active of the three, with less than 50% of the strains being intermediate or resistant to this drug.

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity of N. brasiliensis to amikacin (▾), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (○), and ceftriaxone (•). The graph shows the cumulative MICs of each drug for the strains. The breakpoints for these three drugs are represented by a dotted vertical line.

Assays with drug combinations

Given that combination therapy seems to work better for actinomycetoma, we selected amikacin, SXT, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and linezolid to determine the effects of combinations of these drugs on N. brasiliensis. Table 3 shows that some of the combinations tested, particularly amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in combination with linezolid, had synergistic activities. None of the combinations had a remarkable synergistic effect against the clinical isolates.

TABLE 3.

Effects of combinations of several drugs on the MICs for N. brasiliensis isolatesa

| Antimicrobial combination | No. of animals in which the drug combination had the following effect:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Synergistic | Additive | Antagonistic | |

| Amikacin-SXT | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid-SXT | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Linezolid-SXT | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Linezolid-amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 9 | 2 | 0 |

A total of 11 mice were tested.

Effects of the drugs on the natural course of N. brasiliensis mycetoma in BALB/c mice

By the methodology used to infect the animals, mycetoma lesions appeared as early as 1 month after the initial inoculation. We monitored the infections for up to 9 months and observed that after 90 days (data not shown) the mycetoma lesions that had formed did not heal spontaneously; on the contrary, they continued to grow and formed very large, deforming mycetomas.

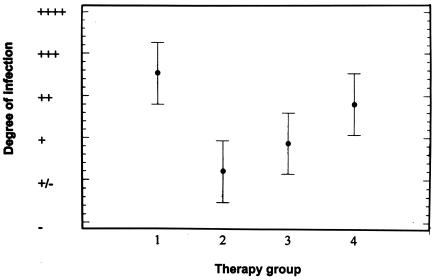

The results of the study of the effects of 4 weeks of therapy on the development of mycetoma in BALB/c mice are shown in Table 4. We observed the production of 4+ lesions in 9 of 15 animals injected with saline solution. Only two animals in the group treated with linezolid had 4+ lesions. When the results were analyzed by the ANOVA test (Fig. 3), the results for the group treated with linezolid were significantly different from those for the control group. The results for the animals treated with amikacin and amoxicillin-clavulanate were intermediate.

TABLE 4.

Effects of the antimicrobials on the natural course of N. brasiliensis infection in BALB/c mice

| Degree of infection | No. of animalsa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline solution | Linezolid (25 mg/kg) | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (25 mg/kg) | Amikacin (25 mg/kg) | |

| 4+ | 9 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 3+ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2+ | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 1+ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| ± | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Negative | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

The numbers of animals with the indicated degree of infection in each treatment group.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the results for the animal model by the ANOVA test. The intervals shown are based on the least significant difference obtained by the Fisher method. The following treatments are represented on the x axis: 1, saline solution; 2, linezolid, 25 mg/kg; 3, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, 25 mg/kg; and 4, amikacin, 25 mg/kg.

DISCUSSION

Many in vitro studies of the sensitivities of Nocardia to antimicrobials have been reported; however, in most of them the investigators have used N. asteroides or other Nocardia species as the test organism or have included few (n < 20) N. brasiliensis strains (2, 3, 4, 5, 29, 31, 34, 35). In the present work we studied the sensitivities of local N. brasiliensis strains to a wide range of antimicrobials. We observed that the strains were particularly sensitive to aminoglycosides, including the recently developed aminoglycoside isepamicin. In our 20 years of experience in treating mycetoma with the combination amikacin-SXT, most of the N. brasiliensis actinomycetoma cases have been sensitive to this combination therapy; one patient, however, was successfully treated with netilmicin (Welsh and Vera-Cabrera, Abstr. 15th Cong. Int. Soc. Hum. Anim. Mycol.). Sisomicin and netilmicin are structurally different from the rest of the aminoglycosides; therefore, the existence of cross-resistance between amikacin and netilmicin is less probable, which correlates with this clinical observation. No other aminoglycosides have been used in clinical trials, but because of the high degrees of sensitivity of the N. brasiliensis strains to these agents, these antimicrobials, particularly the less toxic compounds, such as isepamicin and arbekacin, could potentially be useful for the treatment of actinomycetoma (21).

The beta-lactams were poorly active in our study; one of the penicillins tested, carbenicillin, was active against only 3.4% of the N. brasiliensis clinical isolates. In contrast, Wallace et al. (32), who also used the disk diffusion technique, found that 100% of the N. brasiliensis strains tested (n = 29) were sensitive (inhibition halo, more than 16 mm). Under our conditions (carbenicillin disk of 100 μg), 16 strains did not produce any inhibition zone at all, and only 5 strains showed an inhibition zone of more than 16 mm. These results were confirmed with our quality control strains, E. coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, and suggest the existence of differences in the sensitivities of N. brasiliensis strains to the antimicrobials, depending on the geographical source. Differences in sensitivity results for cefotaxime and ceftriaxone between our study and previous studies were also found. These drugs have been reported to be active against 100% of the N. brasiliensis strains tested (6, 20, 33); however, in the present work these drugs did not have remarkable activities, and in the case of ceftriaxone, more than 50% of the strains were intermediate or resistant by the broth microdilution method. Cefotaxime was of particular interest; 37% of the strains tested (data not shown) presented no inhibition halo in the disk diffusion assays, while the rest of the isolates presented large zones of inhibition (range, 11 to 52 mm; mean, 23.6 mm). It is possible that the species N. brasiliensis contains subspecies, as has been demonstrated before for the species formerly known as the N. asteroides complex (38), although this possibility was not studied further.

Increases in sensitivity were observed when beta-lactams were tested in combination with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, particularly with the combination amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. This in vitro finding has been reported previously (33), and on the basis of these data, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid has successfully been used as treatment for a few cases of cutaneous N. brasiliensis infection (9, 26, 39). However, more extensive clinical trials should be carried out since the combination amoxicillin-clavulanic acid is not active in vitro against 100% of strains, and secondary resistance has seldom been reported to occur (28).

Nitroxolin and spiramycin, two drugs not previously tested against Nocardia, were active against more than 66% of the strains by the disk diffusion method, and the MICs of both drugs by the broth microdilution method were excellent. These findings make these agents good candidates for testing in an animal model in order to determine their usefulness in vivo.

Quinolones such as ciprofloxacin, enoxacin, ofloxacin, and pefloxacin did not show any significant activity against the N. brasiliensis isolates. These drugs have been reported to be particularly active against gram-negative microorganisms (1, 13), and quinolones have traditionally been known to be poorly active against N. brasiliensis. New quinolones, such as gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, and BMS-284756, have shown more promising activities (29; L. Vera-Cabrera, E. González, S. H. Choi, and O. Welsh, submitted for publication).

Teicoplanin, a relatively new glycopeptide, showed very poor activity against the N. brasiliensis isolates. These results confirm a previous observation of the sensitivities of several Nocardia species to this agent (14).

The results of the present study show that other antimicrobials may be useful for the treatment of N. brasiliensis infections. Although in vitro activity is strongly indicative of in vivo activity, as has been demonstrated in the case of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, amikacin, and SXT, it is necessary to confirm the potential clinical use of any of these drugs with animal studies. In our in vivo experiments with the murine mycetoma model, we observed that amikacin had very low levels of activity against the development of lesions. Although this drug has been shown to be active against N. brasiliensis in in vitro assays and in patients, it is possible that the drug did not work in mice because it is metabolized very rapidly and does not reach levels in plasma or infected tissue sufficient to inhibit nocardial growth. It would be important to determine the pharmacokinetics of amikacin or any other drug tested in plasma or tissue in this BALB/c mouse model before its effect on the natural course of infection is studied.

As opposed to amikacin, linezolid produced good results in the experimental model, and the results obtained with linezolid were even better than those obtained with the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, which has been demonstrated to be active against human N. brasiliensis infections. Studies of the pharmacokinetics of linezolid at a dose of 5 mg/kg in mice have resulted in a half-life of 0.63 h and a maximum concentration in serum of 5.19 mg/ml (J. J. Lee, J. H. Kim, S. H. Choi, W. B. Im, and J. K. Rhee, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1315, 2002). These conditions seem to be enough to stop the production of lesions in the mouse footpad. Linezolid administered at a dose of 600 mg to humans has a half-life of 5.4 h, a maximum concentration in serum of 21.2 mg/ml, and a minimum concentration in serum of 4 μg/ml for about 12 h (27); these findings are promising for the use of linezolid for the treatment of human infections, since the levels in serum remain above the MIC for the N. brasiliensis isolates for 12 h. Moylett et al. (23) have reported on the use of linezolid (600 mg administered twice a day orally for 2 months) to treat a patient with cutaneous N. brasiliensis infection that resulted in clinical cure. No other studies on the clinical use of linezolid for the treatment of N. brasiliensis infection have been conducted, although on the basis of the results obtained in the in vitro and mouse model assays, the use of oxazolidinones like linezolid for the treatment of mycetoma caused by N. brasiliensis seems to be promising.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by grant 31015-M from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) and grant SA 600-01 from the Programa de Apoyo a la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (PAICYT), U.A.N.L.

We thank Robert Chandler-Burns for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alos, J. I. 2003. Quinolones. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 21:261-268. (In Spanish.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambaye, A., P. C. Kohner, P. C. Wollan, K. L. Roberts, G. D. Roberts, and F. D. Cockerill. 1997. Comparison of agar dilution, broth microdilution, disk diffusion, E-test, and BACTEC radiometric methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of clinical isolates of the Nocardia asteroides complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:847-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach, M. C., L. D. Sabath, and M. Finland. 1982. Susceptibility of Nocardia asteroides to 45 antimicrobial agents in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:554-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkey, P., D. Moore, and K. Rolston. 1988. In vitro susceptibilities of Nocardia species to newer antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1078-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boiron, P., and F. Provost. 1982. In vitro susceptibility testing of Nocardia spp. and its taxonomic implication. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 22:623-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown-Elliott, B. A., and R. J. Wallace. 1992. Broth microdilution MIC test for Nocardia spp., p. 5.12.1-5.12.7. In H. D. Isenberg (ed.), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Brown-Elliott, B. A., S. C. Ward, C. J. Crist, L. B. Mann, R. W. Wilson, and R. J. Wallace. 2001. In vitro activities of linezolid against multiple Nocardia species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1295-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering. 1996. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 330-396. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 4th ed. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 9.Gomez, A., A. Saul, A. Bonifaz, and M. Lopez. 1993. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomycetoma. Int. J. Dermatol. 32:218-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Ochoa, A., J. Shields, and P. Vázquez. 1952. Acción de la 4-4 diamino-difenil-sulfona frente a Nocardia brasiliensis (estudios in vitro en la infección experimental y en clínica). Gac. Med. Mex. 52:345-353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Ochoa, A. 1955. Effectiveness of DDS in the treatment of chromoblastomycosis and of mycetoma caused by Nocardia brasiliensis, p. 321-327. In Therapy of fungus diseases, an international symposium. Little, Brown & Co., Boston, Mass.

- 12.González Ochoa, A. 1969. Producción experimental del micetoma por Nocardia brasiliensis en el ratón. Gac. Med. Mex. 99:773-781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoban, D. J. 1989. Comparative in vitro activity of quinolones. Clin. Investig. Med. 12:10-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen, K. T., H. Schonheyder, C. Pers, and V. F. Thomsen. 1992. In vitro activity of teicoplanin and vancomycin against gram-positive bacteria from human clinical and veterinary sources. APMIS 100:543-552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavalle, P., A. Saul, and J. Peniche. 1961. La sulfadimetoxipiridazina en el tratamiento de los micetomas, p. 525-535. In I Congress of Mexican Dermatology, Mexico City, Mexico.

- 16.Lavalle, P. 1966. Clinical aspects and therapy of mycetoma. Dermatol. Int. 5:117-120. (In Spanish.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.López-Martínez, R., L. J. Méndez-Tovar, P. Lavalle, O. Welsh, A. Saul, and E. Macotela-Ruiz. 1992. Epidemiología del micetoma en México: estudio de 2105 casos. Gac. Med. Mex. 128:477-481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahgoub, E. S. 1972. Treatment of actinomycetoma with sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 21:332-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahgoub, E. S. 1976. Medical management of mycetoma. Bull. W. H. O. 54:303-311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeil, M. M., J. M. Brown, W. R. Jarvis, and L. Ajello. 1990. Comparison of species distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility of aerobic actinomycetes from clinical specimens. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12:778-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mingeot-Leclercq, M. P., and P. M. Tulkens. 1999. Aminoglycosides: nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1003-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra, S. K., R. E. Gordon, and D. A. Barnett. 1980. Identification of nocardiae and streptomycetes of medical importance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11:728-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moylett, E. H., S. E. Pacheco, B. A. Brown-Elliott, T. R. Perry, E. S. Buescher, M. C. Birmingham, J. J. Schentag, J. F. Gimbel, A. Apodaca, M. A. Schwartz, R. M. Rakita, and R. J. Wallace, Jr. 2003. Clinical experience with linezolid for the treatment of Nocardia infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:313-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NCCLS. 2003. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard. NCCLS document M24-A. NCCLS, Wayne, Pa. [PubMed]

- 25.Ndiaye, B., M. Develoux, M. A. Langlade, and A. Kane. 1994. Actinomycotic mycetoma. A propos of 27 cases in Dakar; medical treatment with cotrimoxazole. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 121:161-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolt, D., R. M. Wadowsky, and M. Green. 2000. Lymphocutaneous Nocardia brasiliensis infection: a pediatric case cured with amoxicilin/clavulanate. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:1023-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pigrau, C. 2003. Oxazolidinones and glycopeptides. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 21:157-164. (In Spanish.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steingrube, V. A., R. J. Wallace, B. A. Brown, Y. Pang, B. Zeluff, L. C. Steele, and Y. Zhang. 1991. Acquired resistance of Nocardia brasiliensis to clavulanic acid related to a change in beta-lactamase following therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:524-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valera, L., E. Gradelski, E. Huczko, T. Washo, H. Yigit, and J. Fung-Tomc. 2002. In vitro activity of a novel des-fluoro(6) quinolone, garenoxacin (BMS-284756), against rapidly growing mycobacteria and Nocardia isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:140-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vera-Cabrera, L., A. Gomez-Flores, W. G. Escalante-Fuentes, and O. Welsh. 2001. In vitro activity of PNU-100766 (linezolid), a new oxazolidinone antimicrobial, against Nocardia brasiliensis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3629-3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace, R. J., E. J. Septimus, D. M. Musher, and R. R. Martin. 1977. Disk diffusion susceptibility testing of Nocardia species. J. Infect. Dis. 135:568-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace, R. J., K. Wiss, R. Curvey, P. H. Vance, and J. Steadham. 1983. Differences among Nocardia spp. in susceptibility to aminoglycosides and beta-lactam antibiotics and their potential use in taxonomy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 23:19-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace, R. J., D. R. Nash, W. K. Johnson, L. C. Steele, and V. A. Steingrube. 1987. β-Lactam resistance in Nocardia brasiliensis is mediated by β-lactamase and reversed in presence of clavulanic acid. J. Infect. Dis. 156:959-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace, R. J., Jr., and L. C. Steele. 1988. Susceptibility testing of Nocardia species for the clinical laboratory. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace, R. J., Jr., L. C. Steele, G. Sumter, and J. M. Smith. 1988. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Nocardia asteroides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1776-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welsh, O., E. Sauceda, J. Gonzalez, and J. Ocampo. 1987. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 17:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welsh, O. 1991. Mycetoma: current concepts in treatment. Int. J. Dermatol. 30:387-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson, R. W., V. A. Steingrube, B. A. Brown, Z. Blacklock, K. C. Jost, Jr., A. McNabb, W. D. Colby, J. R. Biehle, J. L. Gibson, and R. J. Wallace, Jr. 1997. Recognition of a Nocardia transvalensis complex by resistance to aminoglycosides, including amikacin, and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2235-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wortman, P. D. 1993. Treatment of Nocardia brasiliensis mycetoma with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, amikacin and amoxicillin and clavulanate. Arch. Dermatol. 129:564-567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]