Abstract

Advances in positive psychology have grown exponentially over the past decade. The addictions field has experienced its own growth in a positive direction, embodied by the recovery movement. Despite parallel developments, and great momentum on both sides, there has been little crosspollination. This review introduces positive psychology and the recovery movement, describes the research on positive psychology in the addictions, and discusses future avenues of theory, research, and intervention based on a positive-psychology framework. A systematic review of positive psychology applied to substance use, addiction, and recovery found nine studies which are discussed according to the following themes: theoretical propositions, character strengths and drinking, positive psychology and recovery, positive interventions, and addiction: feeling good and feeling bad. The current scholarship is scant, but diverse, covering a wide range of populations (adults, adolescents, those in and out of treatment), topics (character strengths, recovery, positive affect), and addictive behaviors (work addiction, cigarette smoking, and alcohol use disorders). There is diversity, too, in country of origin, with work originating in the US, UK, Poland, and Spain. The rigorous application of the lens, tools, and approaches of positive psychology to addiction research generally, and to the aims of the recovery movement specifically, has potential for the development of theory and innovation in prevention and intervention. Further, because the work in positive psychology has primarily focused on microsystems, it may be primed to make contributions to the predominantly macro-systems focus of the recovery movement.

Keywords: Positive Psychology, Recovery Movement, Substance Use Disorders, Alcoholism, Drug Addiction, Recovery, Review

Over the past decade, a similar shift has occurred in psychology and in addiction studies. During this time, both fields independently recognized that their work was focusing disproportionately on illness and pathology, with scholars in psychology calling for the scientific study of the phenomenon of human flourishing (Keyes & Haidt, 2003), and scholars in addictions research calling for a new focus on recovery and sobriety (Galanter, 2007; White, 2008b). Within psychology, this shift has become the fast-growing subspecialty of positive psychology. Within the addictions, this shift has become the grassroots recovery movement.

The two movements have existed side-by-side with minimal crosspollination. For example, the Research Society on Alcoholism’s 34th annual scientific meeting took place June 25–29, 2011, in Atlanta, GA, USA. While a roundtable at this meeting addressed research on recovery, (“Improving the Rigor of Research on Recovery: Models, Dimensions, and Measures”), an electronic search for the term “positive psychology” through the conference proceedings describing 53 symposia, 4 plenaries, 2 roundtables, and 1,007 posters yielded no results. Conversely, the Second World Congress on Positive Psychology took place July 23–26, 2011, in Philadelphia, PA, USA and featured 6 plenaries, 24 symposia, 27 workshops, 15 lectures by invited speakers, and 316 posters. Based on a review of the final program, only one poster was dedicated to substance users (Hoxmark, Bergvik, Pettersen, & Wynn, 2011).

The Hoxmark poster and the theoretical and empirical work described in this review suggest that positive psychology has begun to be applied to theory, research, and intervention in substance use disorders. Although positive psychology and the recovery movement share similar interests and emphases, they differ in important ways that frame the current discussion. Within the field of addiction, the recovery movement is a multi-faceted grassroots effort led by individuals who are themselves in recovery from substance use disorders. The movement is built on a recovery-oriented, rather than a pathology-oriented, framework from which addiction and its resolution are understood. Working from an established set of values and goals, participants in the recovery movement work collectively to remove obstacles to treatment, support multiple paths to recovery, and make larger social systems more supportive of recovery lifestyles (White, 2007). While the movement adopts the disease model of addiction and situates addiction pathology at the level of the individual (rather than, for example, at the level of larger social forces such as poverty and inequality), the movement primarily focuses on macro-systemic change targeting policies, treatment systems, community resources, and larger social phenomena including stigma (White, 2008a, 2011b). While the recovery movement is primarily a social movement with a political advocacy agenda, it has an academic component. Researchers have begun to measure the impact of the movement and, in accordance with the movement’s basic tenets, have been inspired to design and test interventions that take a life-span, rather than an acute-care, approach to treating substance use disorders.

While the recovery movement has grass roots, positive psychology was sprouted in academic soil. Positive psychology quickly gained appeal among individuals in the general public who are eager to improve their lives, giving positive psychology the feeling of a social movement spreading beyond academia. As a social science, positive psychology provides the research community with conceptual frameworks, definitions of key constructs, measurement instruments, positive interventions, and a growing evidence base. While positive psychology focuses in part on positive organizations, its primary emphasis has been intra-psychic microlevel change at the level of the individual. The focus of the current review is the application of the science of positive psychology to rigorous addictions research and the ways in which the constructs, theories, and interventions of positive psychology dovetail with, and further the aims of, addiction studies and the recovery movement. As such, this review describes and marks the early influence of positive psychology on the addictions field. What follows is an introduction to the field of positive psychology (including scholarly critique and positive interventions), an introduction to the recovery movement and its evidence base, a review of extant research on efforts to apply positive-psychology approaches to the addictions, and proposed avenues for future research and intervention based on a positive psychology framework.

Positive Psychology

Martin Seligman, the psychologist and architect of learned helplessness theory (Seligman, 1975), assumed leadership of the American Psychological Association in 1998 (American Psychological Association, n.d.). He articulated that as president, his objective for his term was to focus the profession on the scientific study of wellbeing. In a theoretical continuum with severe mental illness on the left and optimal human thriving on the right, a hypothetical distribution of individuals populates a bell curve of illness and wellbeing. Seligman pointed out that previous research had focused on the left half of the curve and that the right side of the curve, populated by individuals in good health who are thriving, mostly had been neglected. Recognizing that there is more to mental health than the absence of mental illness, positive psychology is dedicated to the rigorous scientific study of “strengths, well-being, … optimal functioning” (Duckworth, Steen, & Seligman, 2005, p. 631) and flourishing (Keyes & Haidt, 2003). Flourishing individuals are “filled with emotional vitality … [and] functioning positively in the private and social realms of their lives” (p. 6).

Positive psychology distinguishes itself from the psychology that came before it, that is, the work dedicated to reducing suffering and decreasing pathology that was the aim of psychological work historically. This previous work is referred to by positive psychologists not as “negative psychology” but as “psychology as usual” (Seligman & Pawelski, 2003). Positive psychology does not intend to supplant psychology as usual but to become an important adjunct to it: “positive psychology is intended as a supplement, another arrow in the quiver, and not a replacement for this endeavor” (Seligman & Pawelski, 2003, p. 159). Pawelski (2008) adds: “The claim is not that positive psychology is the right way of doing psychology, and that all other ways are wrong. The claim, rather, is that positive psychology emphasizes some important perspectives that have long been under-emphasized and neglected in psychology” (emphasis in the original).

Long before positive psychology, the great philosophers (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle) and psychological thinkers (Freud, Jung, Adler, Frankl, Rogers, Maslow) articulated theories of the good life, pleasure, wholeness, purpose, health, and actualization (Duckworth, et al., 2005; Ryff, 2003). In addition, empirical work existed on adaptation, resilience, thriving, spirituality, and growth (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010b). Positive psychology’s contribution pulled these disparate areas of inquiry together under one umbrella (Peterson & Park, 2010) and provided a conceptual map around which the emerging field has organized. Duckworth et al. (2005) describe the role of the movement as follows:

Positive psychologists did not invent positive emotion or well-being or good character, nor were positive psychologists even among the first to usher in their scientific study. Rather, the contribution of positive psychology has been to champion these topics as worthy of mainstream scientific investigation, to bring them to the attention of various foundations and funding agencies, to help raise money for their study, and perhaps to provide an overarching conceptual structure (pp. 633–634).

Critiques of Positive Psychology

Positive psychology is a young field marked by exponential growth and widespread attention in the popular media, including cover stories in Time magazine (Wallis, 2005) and popular books for lay audiences (e.g., Lyubomirsky, 2008; Seligman, 2002). The combination of its rapid growth and lay popularity has spawned criticism and debate. As the current review will show, positive psychology is in the earliest stages of its influence on substance use research. Therefore it is an opportune time to take account of criticism so that new work building on positive psychology may heed the cautions raised in the scholarly discourse. While it is beyond the scope of the current review to describe the body of debate in depth, a summary and sources for further reading are provided. At least two worthwhile debates about positive psychology have taken place in print. In 2003, Psychological Inquiry (Volume 14, Number 2) showcased a critique of positive psychology written by Richard S. Lazarus, architect of stress and coping theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Lazarus criticized positive psychology for taking an overly simplistic approach to the complexities of human emotion and the harsh realities of human life (Lazarus, 2003a). Fourteen scholarly essays and Lazarus’ response to them follow (Lazarus, 2003b). A more recent debate focusing on positive psychology and health was published in Annals of Behavioral Medicine (2010, Volume 39). The discussion takes place over six papers including a supportive paper (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010b), a cautionary paper (Coyne & Tennen, 2010), and the authors’ responses to each other’s positions. Critics in this series point out methodological and measurement weaknesses in some individual studies and some meta-analyses and what the authors identify as a tendency in positive psychology to build on weak studies. In a similar vein, Ryff (2003) criticizes some positive psychologists for misrepresenting the ideas of the field as new when, in fact, there has been a long history of scholarly attention to human strengths. Some have associated positive psychology with socially conservative ideas including the preservation of the status quo, suggesting that a focus on, for example, increasing personal happiness may take the steam out of efforts to harness anger and other “negative” feelings to work for needed social change (Ehrenreich, 2009). While positive psychology identifies social institutions as one of its primary foci, scholars note that the institutions of interest are more “local and familial” and less “political, cultural, and economic” (Becker & Marecek, 2008, p. 1772).

Most critiques in one way or another trace back to the multi-dimensionality of positive psychology as both a popular self-help movement and a scholarly discipline. It seems there has been some blurring between positive psychology as a rigorous form of scientific inquiry and the larger positive psychology movement featuring the marketing of life-enhancing goods and services to the general public. Wide popular appeal for life improvement, and wide interest in paying for commodities that might lead to a happier life, may have led in some cases to the overstatement of research claims; in addition, media coverage, both in print and online, may quote scholarship out of context. Even those supportive in the positive psychology debate state, “We agree that there is a dangerous popular literature that oversells research findings and promotes dubious claims about positive thinking and health” (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010a, p. 28).

In response to criticism, scholars affirm scientific rigor as what differentiates positive psychology research from folk wisdom and lay positive thinking ideologies (Diener, 2010; Peterson & Park, 2010). In support of positive psychology, other scholars reiterate the central ideas that launched the field--that it is worthwhile to study positive functioning (Ryff, 2003), well-being (Peterson & Park, 2010) and health (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010b). Because the field is new and has been embraced by popular culture, critical thinking is essential both in assessing positive-psychological research and in building good science not only on its foundation, but on the foundation of the decades of relevant scholarship that preceded it.

Positive Interventions

Positive-psychological science seeks to understand and to intervene, with the objective of improving the life satisfaction and happiness of both well and clinical populations. A positive intervention is defined as “an intervention, therapy, or activity primarily aimed at increasing positive feelings, positive behaviors, or positive cognitions, as opposed to ameliorating pathology or fixing negative thoughts or maladaptive behavior patterns” (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009, p. 469). A subset of interventions has been identified as those that can be self-administered without professional administration. Referred to as “positive activity interventions,” or PAIs, these are defined as “relatively brief, self-administered, and nonstigmatizing exercises that promote positive feelings, positive thoughts, and/or positive behaviors, rather than directly aiming to fix negative or pathological feelings, thoughts, and behaviors” (Layous, Chancellor, Lyubomirsky, Wang, & Doraiswamy, 2011, p. 677). Examples of two widely-tested PAIs which may have potential for individuals with substance use disorders are the gratitude intervention, “Three Good Things,” and the optimism intervention, “Best Future Self.” The “Three Good Things” exercise, also known as the “Three Good Things in Life” exercise, instructs participants to “write down three things that went well each day and their causes every night for one week” (happierdotcom, 2009; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005, p. 416). The “Best Future Self” exercise instructs participants as follows:

Think about your life in the future. Imagine that everything has gone as well as it possibly could. You have worked hard and succeeded at accomplishing all of your life goals. Think of this as the realization of all of your life dreams. Now, write about what you imagined (King, 2001, p. 810).

Positive interventions such as these, along with exercises designed to promote kindness, generosity, and mindfulness (Layous, et al., 2011), have been tested in randomized control trials. For example, a 7-week loving-kindness meditation workshop was shown to increase positive emotions, which in turn predicted increases in psychological, cognitive, social, and physical resources, which went on to increase life satisfaction and decrease depression (Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, 2008). A meta-analysis of 51 randomized controlled studies of positive interventions extracted data from studies of individuals who were healthy and of individuals who suffered from depression. The meta-analysis reported, on average, moderate effect sizes for positive interventions (r=.29 for increases in well-being and r=.31 for decreases in depression) (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

While these results are promising, closer scrutiny of the literature reveals subtleties which suggest a more cautious endorsement of the interventions emerging from positive psychology. For example, studies testing the effects of similar interventions on different outcomes have reported contradictory results. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2006) found that a version of the “Best Possible Self” exercise outperformed a gratitude exercise, while Seligman and colleagues (2005) found that “Three Good Things,” a gratitude exercise, outperformed the “You at Your Best” intervention, which asks participants to describe a time in the past when they were at their best. Differences might be accounted for by variations in the exercises (“Best Possible Self” focuses on the future while “You at Your Best” focuses on the past) and in the outcomes measured.

In other studies, the makeup of the comparison condition reveals information about the potential of an intervention. In a body of research on gratitude, statistically significant differences have been reported not between those who received the gratitude interventions and control conditions, but between gratitude and “hassles” conditions (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Froh, Sefick, & Emmons, 2008). Hassles conditions ask individuals to list things that irritate, annoy, or bother them (Froh, et al., 2008). However, among groups more at risk than healthy populations, significant differences between gratitude exercises and controls have been observed. This has been found in studies of individuals with neuromuscular disease (Emmons & McCullough, 2003), hypertension (Shipon, 2007), lower positive affect (Froh, Kashdan, Ozimkowski, & Miller, 2009), and higher self-criticism (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011). In short, an emerging pattern suggests that those at a slight or great disadvantage, either because of physical illness, low positive affect, or high self-criticism, seem to benefit more from a gratitude intervention than healthier individuals.

With the exception of one pilot study of an 8-session positive intervention conducted with a group of adolescents with substance use problems in the UK (Akhtar & Boniwell, 2010) (described more fully in this review), neither positive interventions nor PAIs have been tested among individuals with substance use disorders. The possibility that those more at risk may have more to gain from positive interventions is an endorsement for exploring the value of such interventions among individuals in treatment for substance use disorders, as such individuals are suffering from a wide range of ill effects secondary to their substance use. However, clinicians should consider several points before employing these interventions with individuals with substance use disorders. There is evidence that these exercises work best for individuals who are highly motivated (Lyubomirsky, Dickerhoof, Boehm, & Sheldon, 2011), self-selected (Lyubomirsky, et al., 2011; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), and who continue the exercises independently upon conclusion of the formal intervention (Seligman, et al., 2005). It is not clear whether less motivated or more ambivalent individuals with substance use disorders would make the kind of effort required for maximum benefit. There are also socioeconomic considerations, as much of the positive psychology intervention research has been conducted among healthy college students or individuals surfing the web in search of such exercises. Many studies have delivered the intervention electronically using the web (Seligman, et al., 2005). It is not clear whether individuals with substance use disorders, after suffering socioeconomic deterioration as a result of their addictions, might have regular access to computers with the internet connection necessary to participate. Further, some positive interventions require written essays, such as the “Best Possible Self” and “You at Your Best” exercises. Exemplars of such essays quoted in the literature depict a level of excellence in written communication associated with higher levels of education (King, 2001; Seligman, 2004). Whether these interventions might work with individuals in substance use disorder treatment, especially those with less education and lower levels of literacy, is a good question for future research.

The Addiction Recovery Movement and Its Evidence Base

Beginning in the mid-1990s, but gaining momentum in the mid-2000s (White, 2008b), addiction recovery became a social movement separate and apart from positive psychology. The recovery movement comprises multiple dimensions which will be described below.

One phenomenon co-occurring with and contributing to the recovery movement is the growth of specialized mutual-aid recovery groups. White and Kurtz (2005) describe the proliferation of secular and religious mutual aid groups as well as new groups built on the 12-step model (White, Kelly, & Roth, n.d.). This growth is in accord with one of the core ideas of the recovery movement: that there are multiple paths to recovery (W. L. White, 2007). Further, the recovery movement has unified individuals across mutual-aid groups for the first time, so that, for example, Alcoholics Anonymous members, Narcotics Anonymous members, Women for Sobriety members, and Celebrate Recovery members now work, and in some cases, march, side-by-side with a shared identity as “people in recovery” (White, et al., n.d.). In another manifestation of the larger movement, a culture of recovery is taking newer and broader forms, including travel: “Sober Vacations, Getaways, and Retreats” (www.sobertravelers.org); radio: “Listen to the very best recovery and positive music” (www.take12radio.com); comedy: “Book a recovery comedian for your next recovery convention” (www.recoverycomedy.com); sports: “using basketball as a catalyst for rebuilding … lives” (White, 2011a); theater: “educating the public about addiction and recovery through dramatic performances and theater workshops” (www.improbableplayers.org); jewelry: “12-step gifts for any occasion” (www.12stepjewelry.com); and numerous other examples (White, et al., n.d.).

The recovery movement has organized itself into advocacy groups which actively work to support treatment-friendly legislation, fight stigma, and change public opinion. The national advocacy group is Faces and Voices of Recovery (FAVOR, 2011, n.d.), but over 125 smaller groups also exist (White, 2007), many of whom are members of the Association of Recovery Community Organizations. As a result of such advocacy, recovering individuals increasingly have a place at the table when policies and legislation are written and reformed (Valentine, 2011). Other phenomena of the movement are new recovery institutions, which address needs outside the purview of formal treatment and mutual-aid (White, et al., n.d.). These new institutions include recovery community centers, recovery homes, recovery schools, recovery ministries, and recovery industries (White, et al., n.d.). The recovery movement has had an influence on treatment, embodied by the idea of Recovery Management (RM), a philosophy of intervention which uses a continuity-of-care approach to adequately address the chronicity of addiction. RM involves early intervention in the addiction process and attends individuals past the traditional cut point of treatment discharge (White & Kelly, 2011). RM is a component of a larger organizing construct, Recovery Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC). ROSC is “a larger cultural and policy climate within which long-term addiction recovery [can] flourish in local communities” (White & Kelly, 2011, p. 72). ROSC refers to linkages between elements of the larger social world that affect and influence recovery: housing, employment, treatment, self-help, policy, and public opinion.

Evidence for the effectiveness of the recovery movement takes three forms: evidence for its core ideas, evidence of the impact of new recovery institutions, and outcome research on interventions that follow a continuity-of-care, versus an acute-care, model. It is beyond the scope of the current review to report extensively on these areas, however, examples from each category are provided as an overview.

Evidence for the Recovery Movement’s Core Ideas

One of the core ideas of the recovery movement is that “addiction recovery is a living reality for individuals, families, and communities” (White, 2007). A first empirical question is, how many people are recovering from substance use disorders? At least two scientific methods have been employed to answer this question: survey research and the synthesis of findings from literature reviews. The Partnership at Drugfree.org and The New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) surveyed 2,526 US adults in a nationally representative sample and found that 10% answered yes to the question, “Did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” (Feliz, 2012). This percentage, extrapolated to the US population suggests that 23.5 million people have overcome a drug or alcohol problem. White (2012) condensed the findings from 415 scientific reports published between 1868 and 2011 which documented rates of recovery or remission. He estimated that the percentage of adults in the general population in the US in remission from substance use disorders ranged from 5.3% to 15.3%. Both approaches to estimating recovery prevalence have limitations. Not all individuals who once had a problem, but no longer do, would identify as being in recovery. The literature-review-synthesis approach faced a similar challenge—definitions of recovery ranged from study to study as did research methodologies. The findings from both studies concur—10% falls within the range of 5.3% to 15.3%—and provide a starting place from which to estimate remission rates from substance use disorders in the US population.

Effects of New Institutions: Recovery Schools, Recovery Community Centers, and Recovery Homes

The Association of Recovery Schools is the membership organization of secondary and post-secondary institutions comprised of students “committed to being abstinent from alcohol and other drugs and working a program of recovery” (Association of Recovery Schools, n.d.). Collegiate recovery communities provide students with a safe space in a larger university environment often marked by heavy-drinking social norms (Cleveland, Harris, Baker, Herbert, & Dean, 2007). Research on the effectiveness of such communities is so far limited to descriptive profiles of community members (Cleveland, et al., 2007) and cross-sectional surveys (Cleveland, Wiebe, & Wiersma, 2010; Wiebe, Cleveland, & Dean, 2010). While this work provides preliminary data about such communities, including the finding that social support from alcohol and drug abstainers is important (Cleveland, et al., 2010), research in this area has been dominated by investigations of one of the largest and oldest Collegiate Recovery Communities in the US, namely, the group at Texas Tech University. As such, studies to date have been limited in terms of generalizability and limited to a sample of primarily Caucasian students (Cleveland, et al., 2007).

Another new recovery institution is the Recovery Community Center (RCC) which provides a range of free services to individuals in recovery including telephone support, job search coaching, sober housing search engines, recovery workshops, resource linkages, training, and volunteer opportunities. Among other aims, these services facilitate the entry of individuals in the community into treatment and bridge individuals from treatment discharge back into the community (Valentine, 2011). Preliminary empirical evidence has been in the form of service utilization data; in 2009, four sites in Connecticut together logged 35,000 visitors and, in 2008, volunteers logged over 13,000 hours of service to recovering patrons (Valentine, 2011).

Of all the new recovery institutions, recovery homes, specifically Oxford Houses, have the largest evidence base (W. L. White, personal communication, March 15, 2012). Oxford Houses are rental homes where individuals in recovery live, share expenses, and provide one another abstinence-specific social support and other forms of concrete and emotional assistance. Residents themselves manage the business of the household and there is no limit to length-of-stay. There are currently approximately 1,400 Oxford Houses in the US with 10,000 individuals residing in them (Jason, Olson, Mueller, Walt, & Aase, 2011). An experimental trial to test the efficacy of the Oxford House experience has been conducted with 150 individuals who completed residential treatment in Chicago (Jason, Olson, Ferrari, & Lo Sasso, 2006). Half were randomized to live in an Oxford House and half were randomized to receive aftercare treatment-as-usual. At the 24-month follow-up, the Oxford House group residents, compared with the control group, had lower rates of substance use (31.3% versus 64.8%), lower rates of illegal activity (0.9 days versus 1.8 days in the month before follow-up, Cohen’s d = .17), lower rates of incarceration (3% versus 9%), higher rates of employment (76.1% versus 48.6%), higher average earnings per month (a difference of $550), and higher rates of regaining custody of their children (30.4% versus 12.8%) (Jason & Ferrari, 2010). Retention in the study for both groups over the 24-month follow-up was over 90%.

Recovery Management Checkups (RMCs)

The recovery movement has advocated for treatment models that address addiction as a chronic, rather than acute, disorder. Recovery Management Checkups (RMCs) are quarterly meetings between counselors and individuals with substance use disorders that take place consistently for 2 or 3 years—longer than traditional aftercare models—and use each follow-up as an opportunity for intervention. RMCs involve locating the individual, assessing drug/alcohol use, using Motivational Interviewing techniques to provide feedback, negotiating barriers to treatment re-entry, and, if necessary, actively relinking the individual to treatment (Scott & Dennis, 2011). Longitudinal, randomized controlled trials comparing individuals who received full recovery checkups to those in a control group who received only follow-up interviews (Scott & Dennis, 2009) have been conducted in a sample of individuals from public programs who were mostly unemployed and heavy users. During the first trial, it was discovered that on-site drug testing improved assessment accuracy, and that transportation to treatment improved intake rates. In a second trial which incorporated these and other improvements, at the 2-year follow up, individuals who received recovery checkups were more likely than controls to re-enter treatment if needed, re-enter treatment more frequently, attend more days of treatment, attend more self-help meetings, achieve more days of abstinence, and live in the community for shorter periods in a state where they needed, but did not receive, treatment. These statistically significant differences were moderate in effect size, with Cohen’s d values ranging from .23 to .46. All of these relationships remained robust at the 3-year follow up except for total days of self-help meetings, which did not differ statistically between experimental and control groups at that time.

This research comprises early work in a new field—using primarily descriptive and correlational designs and a few randomized controlled trials. Despite limitations, findings suggests that a large number of individuals are in recovery, new recovery institutions seem to be filling a gap unfilled by traditional professional treatment and mutual-aid groups, and continuity-of-care intervention models may offer benefits beyond those provided by acute-care models.

Positive Psychology’s Conceptual Map, Applied to Addictions

Further description of positive psychology’s contributions illuminates its potential for addictions research generally and the recovery movement specifically. The conceptual map drawn by the founding positive psychologists is tripartite. The field pursues the science of positive emotion, character strengths, and positive institutions. These three domains are associated with three “kinds of lives” (Duckworth, et al., 2005, p. 635): “the pleasant life” and its attending positive emotions; “the engaged life” and the character strengths necessary for full engagement; and “the meaningful life” representing the positive institutions that allow individuals to thrive and to contribute. Each is described below with examples of its conceptual relevance to substance use, addiction treatment, and recovery.

The Pleasant Life

The pleasant life is studied as positive affect—good feelings—about the past, the present, and the future. Positive emotion about the present is further divided into somatic and complex pleasures. While the perils of alcohol tend to be forefront in the minds of addictions scholars, treatment professionals, and individuals personally affected, research on positive affect and alcohol reminds us that the majority of the population associates drinking with pleasure. This form of positive emotion is studied by positive psychologists as somatic pleasure, related to “immediate but momentary sensory delights” (Duckworth, et al., 2005, p. 635).

While somatic pleasure has a place in the positive psychology realm, Seligman and Pawelski (2003) caution that pleasure alone does not fully constitute a life well lived: “We believe that simple hedonic theory, without consideration of strength, virtue, and meaning, fails as an account of the positive life” (p. 160). The authors describe “shortcuts to feeling good” as experiences that “produce positive emotion in us without our going to the trouble of using our strengths and virtues. Shopping, drugs, chocolate, loveless sex, and television are examples” (p. 161). Without naming addiction as one potential peril, they continue, “there is a cost to getting happiness so cheaply … when the shortcuts become one’s principal road to happiness” (p. 161), thus providing concordance between positive psychology and theories of addiction.

The Engaged Life

The engaged life is associated with positive traits, articulated as strengths of character. Seligman and Peterson wrote a diagnostic manual of wellbeing, Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (2004b). The volume provides for mental flourishing what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders provides for mental illness: an operationalization of 6 virtues (wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence) and the 24 character strengths which comprise them. The virtue of wisdom comprises the character strengths of 1. open-mindedness, 2. perspective, 3. love of learning, 4. creativity, and 5. curiosity. Courage comprises 6. bravery, 7. persistence, 8. integrity, and 9. vitality. Humanity comprises 10. love, 11. social intelligence, and 12. kindness. Justice comprises 13. fairness, 14. citizenship, and 15. leadership. Temperance comprises 16. forgiveness, 17. humility, 18. prudence, and 19. self-regulation. Transcendence comprises 20. appreciation of beauty and excellence, 21. gratitude, 22. hope, 23. humor, and 24. spirituality.

Over the course of recovery from addiction, tremendous change takes place (Brown & Peterson, 1990; Miller, 2002). Using the lens of positive psychology, addiction and subsequent recovery can be understood in terms of the erosion and reacquisition of character strengths. Consider the iconic “Jellinek Curve” (Glatt, 1958). The U-shaped curve depicts the descent into alcoholism, marked by the behavioral milestones associated with deterioration, followed by the ascent into recovery, marked by milestones of reintegration and returning well-being. The behaviors catalogued along the descent can be seen as progressive deviations from the hallmarks of good character. Quoting from the chart, surreptitious drinking, drinking bolstered with excuses, grandiose and aggressive behavior, failing promises and resolutions, geographic escapes, avoidance of family and friends, inability to initiate action—all are painful examples of the absence of Seligman and Peterson’s (2004b) identified character strengths of bravery, integrity, citizenship, humility, prudence, and self-regulation. The ascent marks the restoration of good character. Specifically, honest desire for help, onset of new hope, absence of desire to escape, facing facts with courage, developing new interests, rebirth of ideals, application of real values, confidence of employers, and the endpoint, where an “enlightened and interesting way of life opens up with road ahead to higher levels than ever before—” (p. 140) resonate with Seligman and Peterson’s identified character strengths of bravery, integrity, citizenship, humility, prudence, self-regulation, curiosity, perspective, persistence, gratitude and hope. The applicability of the theory of character strengths to the phases of addiction and recovery illustrates the potential of positive psychology to contribute to the understanding of addiction and recovery.

The Meaningful Life

The meaningful life is the life of service to, and membership in, positive organizations. These include the family, the workplace, social groups, and society at large. Positive organizations provide an environment in which character strengths and positive emotions flourish. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), other 12-step groups, and recovery-oriented treatment facilities can be viewed as positive organizations. The application of positive psychology to the study of AA can elucidate the ways in which the fellowship and the program increase positive affect and promote character strengths. Treatment programs also can be examined to determine their role as positive organizations. Embedded in the idea of the meaningful life is the idea of service. Service is integrated into the AA recovery program and has been explored by social scientists as a pro-social behavior that has implications for beneficial recovery (Pagano, Post, & Johnson, 2011; Zemore & Pagano, 2009). Service to a community of peers, typically involving vocational and educational activity, is also a potent element of a number of treatment programs, particularly residential programs and therapeutic communities (De Leon, 2000). Service also is a prominent element in emerging recovery community centers, spawned by the recovery movement (Valentine, 2011).

Positive Research in the Addictions

Previous research on addiction and recovery has focused on positive themes. There is a rich body of work on spirituality and its relationship to recovery and improved drinking outcomes (Galanter & Kaskutas, 2008; Miller, 2002), a growing literature on the beneficial role of altruistic behaviors, specifically helping others in recovery (Pagano, et al., 2011; Zemore & Pagano, 2009), and a focus on quality of life as a predictor of commitment to abstinence and sustained remission (Laudet, Becker, & White, 2009; Laudet & Stanick, 2010). Work associated with the recovery movement examines the compound construct of “recovery capital,” comprised of social support, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning, and 12-Step affiliation, and its impact on life satisfaction (Laudet, Morgen, & White, 2006; Laudet & White, 2008). In addition, a search in the Psycinfo database cross-referencing alcohol and substance use disorders with hope, hardiness, forgiveness, resilience, purpose in life, positive activities, gratitude, and humor yields scientific contributions in each area (e.g., gratitude: Arminen, 2001; resilience: Beauvais & Oetting, 1999; positive activities: Hoxmark, Wynn, & Wynn, 2011; hardiness: Maddi, Wadhwa, & Haier, 1996; purpose in life: Martin, MacKinnon, Johnson, & Rohsenow, 2011; humor: Pollner & Stein, 2001; forgiveness: Webb, Robinson, & Brower, 2011; hope: Wilson, Syme, Boyce, Battistich, & Selvin, 2005). A surprising amount of the work studying positive themes in the addictions is not connected explicitly to the recovery movement nor to positive psychology. Scholarship which specifically identifies positive psychology and its conceptual framework to study substance use is just emerging. The following section provides an analysis of the first forays into this area.

Literature Review Search Strategy

A broad search strategy was employed to capture the fullest picture of positive psychology’s forays into addiction research. The search term “positive psychology” was cross-referenced with the terms “alcohol*,” “substance use,” “substance abuse,” “substance dependence,” “addict*,” “drug abuse,” “drug,” or “drug dependence” in Psycinfo and in Pubmed. No restrictions were placed on genre (book review, book chapter, dissertation, peer-reviewed journal article), developmental stage of subject (child, adolescent, adult), nature of intervention (prevention, treatment), type of addiction, nature of substance use (use, abuse, dependence) or original language. Work designated for inclusion in this review focused on substance use or addiction as the primary factor of interest and explicitly identified positive psychology as a conceptual lens used in the analysis or discussion. To keep the focus of the review on risk, prevention, and treatment, work that employed a positive psychology framework to understand the benefits of drug use (e.g., “The cannabis experience: The analysis of flow”, Hathaway & Sharpley, 2010) was excluded. Results of the review are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Current Literature on Positive Psychology and Substance Use, Addiction, and Recovery.

| Author(s) | Year | Genre | Empirical or Theoretical | Description | N | Substance | Population | Clinical Population? | Cites Positive Psychology foundation literature | Country of Origin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akhtar & Boniwell | 2010 | Journal article | Empirical | Pilot of a positive psychology intervention, convenience sample, experimental group and wait list control | 20 | Drugs and/or alcohol | Adolescents aged 14–20 in alcohol and drug treatment | Yes | Yes | U.K. |

| 2 | Ciarrocchi & Brelsford | 2009 | Journal article | Empirical | Coping using drugs and alcohol and spirituality/ religiousness as predictors of well-being. Cross-sectional survey research | 439–602 | Degree to which the R copes with the challenges of life via alcohol and drug use | Adults (college students and community members) | No | No | U.S.A. |

| 3 | Galanter | 2007 | Journal article | Theoretical | Presents a model of spiritually grounded recovery | N/A | Addiction in general | N/A | N/A | Yes | U.S.A. |

| 4 | Jiménez, Herrer, Hernández & Carvajal | 2005 | Journal article | Theoretical | Provides a definition of work addiction and suggests a positive psychology framework for intervention | N/A | Work addiction | N/A | N/A | Yes | Spain |

| 5 | Lindgren, Mullins, Neighbors, & Blayney | 2010 | Journal article | Empirical | Correlational study. Sought the relationships between two curiosity factors: absorption and exploration, and their correlations with sensation seeking, alcohol consumption and alcohol problems | 79 | Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems | Female college students | No | Yes | U.S.A. |

| 6 | Logan, Kilmer, & Marlatt | 2010 | Journal article | Empirical | Virtues of wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance and transcendence examined as protective factors and moderators of drinking. Cross-sectional survey | 425 | Alcohol consumption, risk, and drinking consequences | Undergraduate students | No | Yes | U.S.A. |

| 7 | McCoy | 2009 | Dissertation | Empirical | How flow, spiritual transcendence and hope correlate with variables known to be predictive of relapse. Cross-sectional survey. | 126 | Drugs/alcohol | Adults in recovery from drug and/or alcohol abuse, at least 6 months sober | No | Yes | U.S.A. (Sample comprised individuals in the U.S. and Canada) |

| 8 | Mojs, Stanisławska-Kubiak, Skommer, & Wójciak | 2009 | Journal article | Empirical | Cross sectional survey research. Compared former smokers, current smokers, and those who never smoked in terms of positive affect, negative affect, and happiness. | 14, 20, and 20 | Cigarette smoking | Adult smokers, former smokers, and non-smokers | Unclear whether these were smokers in the general population or patients. | Yes | Poland |

| 9 | Zemansky | 2006 | Dissertation | Empirical | Are length of sobriety and degree of AA affiliation related to positive personality factors? Cross-sectional survey. | 164 | alcohol | Adult members of Alcoholics Anonymous, at least 1 year sober | No | Yes | U.S.A. |

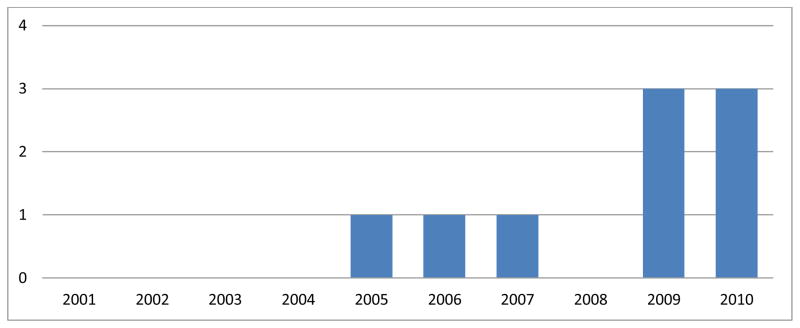

The works were published between 2005–2010, with a trend toward increasing presence in the research literature over time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of Scholarly Works Published on Positive Psychology and Addictions in the Past 10 Years which Met Inclusion Criteria

Review of the Literature

The literature will be discussed according to the following themes: theoretical propositions, character strengths and drinking, positive psychology and recovery, positive interventions, and addiction: feeling good and feeling bad. Specific names of measurement instruments used and Cronbach’s alphas for each study, when reported, are included.

Theoretical Propositions Uniting Positive Psychology and the Addictions

Galanter (2007) describes the AA experience using a model of spiritually-grounded recovery, situated in contrast to pathological and behavioral perspectives on addiction. A number of benefits gained from AA participation are described by Galanter as grounded in spirituality, such as supportive social networks, group ties, adoption of a new understanding of life, and increases in positive affect. Galanter suggests that AA may have a favorable impact on a range of positive variables, such as positive affect, well-being, subjective happiness, life satisfaction, social support, purpose in life, flow, spirituality, and character strengths.

Logan, Kilmer & Marlatt (2010) advance theory by describing each of the six character virtues as they relate to college student drinking. While the authors connect aspects of virtue to issues of college student drinking, the logic suggested can be generalized to other addictions and populations.

Character Strengths and Drinking

Is curiosity a strength or a liability among college students who drink? Curiosity, one of Seligman and Peterson’s (2004b) identified character strengths, is enigmatic in its relationship to substance use disorders. Curiosity is conceptually similar to sensation seeking, found to be associated with problematic drug and alcohol use, and yet is also associated with interest in the world, wisdom, and wonder. Lindgren, Mullins, Neighbors, & Blayney (2010) examined curiosity and tested its association with sensation seeking, drinking, and alcohol problems in a sample of 79 healthy female college students. Curiosity, measured by the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory (Kashdan, Rose, & Fincham, 2004), was studied according to its two component parts: absorption and exploration (α = .74 and .71, respectively). The researchers proposed a two-tailed hypothesis, uncertain whether absorption and exploration would bode well or poorly in their associations with alcohol-related problems (Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index; White & Labouvie, 1989; α = .89). Zero-inflated negative binomial regression models were used to predict the number of reported alcohol-related problems. Neither “absorption” nor “exploration” were significant in the logistic model (having alcohol-related problems or not), but in the counts model (number of alcohol-related problems), higher scores on “absorption” were related to more alcohol-related problems (B = .11) and higher scores on “exploration” were associated with fewer problems (B = −.23). Sensation seeking (Brief Sensation Seeking Scale; Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002; α = 70) was associated with more drinking problems, as expected (r = .29), but notably was not related to absorption or exploration.

Which of the 6 virtues proposed by Seligman and Peterson (Peterson & Seligman, 2004b) might protect against risky drinking? Logan, Kilmer & Marlatt (2010) surveyed 425 undergraduate students, and assessed them for the presence of 24 character strengths using the Values In Action Classification of Character Strength and Virtues instrument (Peterson & Seligman, 2004a). The 24 character strengths were aggregated to produce scores for the 6 virtues: wisdom (α = .82), courage (α = .79), humanity (α = .77), justice (α = .88), temperance (α = .72), and transcendence (α = .78). A modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was used to identify both abstinent respondents and drinkers with high blood-alcohol levels. Risk for alcohol-use disorders was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, Delafuente, & Grant, 1993; α = .84) and drinking consequences were assessed with the Young Adult Alcohol Problem Screening Test (Hurlbut & Sher, 1992; α = .86). Results are as follows. Students who abstained from drinking in the past month had significantly higher justice (Cohen’s d = .40), temperance (Cohen’s d = .51), and transcendence (Cohen’s d = .39) scores than students who drank. Although the abstinent students had higher scores on wisdom (Cohen’s d = .24), courage (Cohen’s d = .17), and humanity (Cohen’s d = .24), these differences were not significant. In the next set of analyses, abstinent drinkers were excluded and high-risk drinkers (who scored 8 or above on the AUDIT measure) were compared with all other drinkers. While high-risk drinkers scored lower on justice and transcendence than other drinkers, their scores were statistically significantly lower only on the measure of temperance (Cohen’s d = .56). In an analysis that excluded lighter drinkers and predicted drinking consequences, a significant interaction was reported between blood-alcohol levels and temperance scores: as peak blood-alcohol levels increased, negative consequences of drinking increased, but this relationship was weaker for those with higher temperance scores (B = −1.27), suggesting that the character strength of temperance may ameliorate some of the ill effects of the association between blood-alcohol levels and alcohol-related consequences. Strengths of the study include the use of a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of p < .008 and the finding of moderate effect sizes. Overall, these findings indicate that higher character strength was associated with less drinking. However the most robust findings were for the character virtue of temperance, which is comprised of forgiveness, humility, prudence, and self-regulation. By definition, it is a character strength marked by behavioral regulation which would be contrary to excessive drinking. While these studies were conducted with college students and not clinical populations, they suggest that character strengths may vary with the presence or absence of abstinence and/or alcohol-related problems, supporting the application of positive psychology to further work in the addictions.

Positive Psychology and Recovery

How do hope, flow, and spiritual transcendence associate with known predictors of relapse? McCoy (2009) administered a questionnaire to 126 recovering individuals with a minimum of 6 months’ abstinence. She sought to explore the contributions that hope (Adult Dispositional Hope Scale; Snyder et al., 1991), flow (a shortened form of the Flow Questionnaire; Delle Fave & Massimini, 2005), and spiritual transcendence (Spiritual Transcendence Scale; Piedmont, 1999) might make to the usual battery of variables well known to predict relapse (e.g., psychiatric symptoms; Brief Symptom Inventory; Derogatis, 1993) or to inhibit it (e.g., meaning in life, Meaning in Life Questionnaire; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006; social support, The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988; and abstinence self-efficacy, Brief Situational Confidence Questionnaire, Breslin, Sobell, Sobell, & Agrawal, 2000). Hope robustly correlated with key variables in the hypothesized directions, e.g., spiritual transcendence (r = .35), flow (r = .36), purpose in life (for the “presence” subscale (r = .51), social support (r = .49), self-efficacy (r = .32) and psychiatric symptoms (r = −.39). Spiritual transcendence and flow correlated neither with one another nor with the majority of the established predictors or relapse. Limitations of the study include the shortening of some measures by the researcher; also, mediators and causal relationships were difficult to establish with this cross sectional study. Results suggest that hope, a construct previously under-examined in the addictions, might be worth including in future research as a potentially potent predictor of good outcomes.

How do AA members rate on happiness, gratitude, optimism, purpose in life, and spirituality, constructs important both to positive psychology and to Alcoholics Anonymous? Zemansky (2006) surveyed 164 AA members with at least one year of sobriety and examined the associations of length of abstinence and depth of AA affiliation (Alcoholics Anonymous Affiliation Scale, Humphreys, Kaskutas, & Weisner, 1998 to constructs of central interest to positive psychology, including spirituality (Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire, Plante & Boccaccini, 1997), gratitude (Gratitude Questionnaire, McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002), optimism (Life Orientation Test, Scheier & Carver, 1985), life satisfaction (Satisfaction With Life Scale, (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985), and purpose in life (Purpose in Life instrument, Crumbaugh & Maholick, 1964). The statistical analytic approach tested the association between AA affiliation and each of the positive psychology outcomes using multiple regression while controlling for significant demographic variables. Using this approach, AA affiliation was significantly associated with optimism, gratitude, purpose in life, and spirituality, although beta weights were not reported. As a second step in each model, length of sobriety was added. Length of sobriety was not significant in any of the models.

Results should be understood cautiously in context of the sample, which comprised individuals who were high in household income and education: 57.4% earned more than $60k annually and 39% had masters or doctoral degrees. Further, the sample was made up of highly involved AA members. The majority (98.2%) had read AA literature, 92.7% had held an AA service commitment, 85.4% reported they had worked all 12 steps, and 81.7% reported practicing prayer and meditation on a daily basis. On the Alcoholics Anonymous Affiliation Scale, the sample achieved a mean of 8.1 out of a possible 9.0. The sample was thriving, reporting uniformly high levels of optimism, gratitude, purpose in life, happiness, and spirituality, which may have resulted in ceiling effects. The respondents’ scores were so high, in fact, that they outpaced comparison groups assessed in previous research on the measures of happiness, optimism, gratitude, and spirituality. While the study is limited by the homogenous sample, it provides empirical evidence of AA members’ flourishing. This may be explained by the concept of post traumatic growth, which describes the beneficial outcomes that can come from struggling with a life crisis (Snyder & Lopez, 2009). Future research may explore the ways in which the recovery experience might promote resilience and well-being. Such work would inform research on both positive psychology and the recovery movement.

Positive Interventions Applied to Addiction

Can positive interventions improve the lives of individuals with addictions? Jiménez, Herrer, Hernández, and Carvajal (2005) provide an introduction to work addiction including its definition, measurement, prevalence, and negative effects. They do not propose a specific positive intervention for work addiction, but do suggest using the positive psychology construct of “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991) as a place to start. They suggest that flow, which represents the experience of losing one’s self in pleasing, enjoyable activity, may be employed therapeutically to reintroduce a sense of intrinsic, healthy satisfaction and pleasure as it relates to work. This experience may counter harmful behaviors associated with work addiction.

Akhtar and Boniwell (2010) piloted a positive psychology intervention with 10 adolescents in substance use treatment in the U.K. and compared their results to 10 adolescents in a wait-list control group. The 8-week intervention promoted positive emotions, savoring, gratitude, optimism, strengths, relaxation, meditation, change, goal-setting, relationships, nutrition, physical activity, resilience, and growth. The authors collected qualitative and quantitative data on the impact of the intervention. The qualitative data were positive, with young people stating the intervention increased their sense of gratitude and happiness, and broadened their interest in the world as they grew more optimistic about the future. A few found the experience transformational and life-changing. The quantitative analyses compared experimental and control groups on the following outcomes: happiness (Subjective Happiness Scale, Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999), optimism (Life Orientation Test; Raistrick, Dunbar, & Davidson, 1983; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994), affect (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), and drinking (Short Alcohol Dependence Data, Raistrick, et al., 1983). Data were analyzed with a 2×2 ANOVA with experimental condition and time as predictors. Significant interactions between condition and time indicated that the experimental group experienced greater increases in happiness, optimism, and positive affect than the control group. The interaction between condition and time was not significant for negative affect, although the experimental condition had lower scores on negative affect than the controls at the conclusion of the intervention. The drinking data were analyzed with non-parametric tests and no differences between the groups were found, although the experimental group had lower scores than the control group at the conclusion of treatment. The effect sizes of the intervention for each outcome were as follows: happiness (d = 1.39), optimism (d = 1.52), positive affect (d = .80), negative affect (d = −.60), and alcohol dependence (d = −.67). In addition, participants in the experimental condition experienced “multiple successes ranging from gaining new jobs and accommodation, to passing exams and completing educational alignments” (pp. 22–23). The authors account for these unforeseen outcomes using broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), suggesting that as the ratio of positive emotions to negative emotions increased, an “upwards spiral of development” (p. 22) ensued. Compared to controls, participants in the experimental condition had greater increases in happiness, optimism, and positive affect, and experienced improvements in life domains beyond what was hypothesized prior to the positive psychology interventions. The study measured alcohol issues with a single measure, which is a limitation, as is the small sample size. Nevertheless, this study of positive psychology interventions is promising. Future research on positive interventions with individuals with substance use disorders can test multiple dimensions of drinking and drug use (such as drinks per drinking day, percent days abstinent, percent heavy drinking days) to ascertain which ones might be affected by positive interventions.

Addiction: Feeling Good and Feeling Bad

Individuals smoke and drink, presumably, to feel good. How do drinkers and smokers fare on measures of affect and well-being? Mojs, Stanisławska-Kubiak, Skommer, and Wójciak (2009) compared three groups: smokers (n=14), former smokers (n=20), and non-smokers (n=20) on three popular positive psychology constructs: happiness (a scale attributed to Fordyce) and positive and negative affect (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, attributed to Lee, Clark and Tellegen, cited in a Polish translation of Seligman’s Authentic Happiness). Former smokers were found to be happier than smokers (92.5% versus 62.5%), a statistically significant difference. Former smokers reported higher levels of both positive and negative affect than both non-smokers and smokers (positive affect: 35.5, 31.8, and 27.5; and negative affect: 19.0, 14.6, and 12.8, respectively). Although the authors did not report whether these differences were statistically significant, they conclude that part of stopping smoking may involve an emotional expansion which includes experiencing both positive and negative emotions more fully than while smoking.

Another counter-intuitive finding comes from a study of drinking. If drinking is associated with pleasure, then does drinking to cope help people feel better? In a survey comprised of college students and community members, Ciarrocchi and Brelsford (2009) found that drinking to cope with difficulties paradoxically reduces positive affect (B = −.08) and increases negative affect (B = .14) when controlling for age and personality factors. Ciarrocchi and Brelsford also provided evidence of the association between spirituality and affect. Multiple dimensions of spirituality (spiritual discontent (α = .64), faith maturity (α = .93), organizational religiousness (α = .76), private religious practices (α = .79), and daily spiritual experiences (α = .91); all subscales of the Brief Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality scale, Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group, 1999) were studied in relationship to a range of positive psychology outcomes: (purpose in life; Crumbaugh & Maholick, 1964; α = .89), satisfaction with life (Diener, et al., 1985; α = .87), and negative (α = .82) and positive (α = .88) affect (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998), while controlling for age, personality, and the degree to which one copes with problems by using drugs or alcohol (subscale of the Brief COPE; Carver, 1997; α = .94). Spiritual discontent, faith maturity, religious service attendance, private religious practices, and daily spiritual experiences were found to be significantly associated with purpose in life and positive affect, even when controlling for drug and alcohol use, although only spiritual discontent was significantly associated with satisfaction with life and negative affect. These findings speak to the positive, independent associations between spirituality and well-being, regardless of drug/alcohol use. A limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, limiting its ability to draw conclusions about causation.

The finding that spiritual dimensions are associated with positive affect has applications to recent studies of Alcoholics Anonymous. Galanter (2007) suggests that AA functions in part by increasing positive emotions. Spiritual/religious practices (such as prayer, meditation, and reading spiritual materials) have been found to function as a mediator of the effect of AA on drinking (Kelly, Stout, Magill, Tonigan, & Pagano, 2011; Krentzman, Cranford, & Robinson, 2011). Ciarrocchi and Brelsford’s (2009) work prompts the question of whether spiritual practices may mediate the relationship between AA and positive affect.

Discussion

Current Research is Scant, but Diverse

Adolescents, college drinking, smoking, work addiction, and recovery have been addressed in these nine studies. The range of populations and applications suggests a wide application for future integration of positive psychology and addictions research.

More, and Better, Research is Needed

One study in this review was conducted with a clinical population (Akhtar & Boniwell, 2010) and this was the only study designed to compare an experimental group with a wait-list control group. Clearly, more work is needed on community and treatment samples, as interventions could be focused on both groups. According to this review, the majority of empirical work in this area is cross-sectional survey research. Longitudinal designs, and more experimental work, especially to test interventions, are needed.

A Critical Eye is Necessary to Discern What is and is Not Positive Psychological Research

There is a great deal of work in addictions that, based on content alone, conceptually falls under the positive psychology umbrella but may not be explicitly identified as such. By definition, all of the work in the current review was situated within established positive psychology research and theory. Eight papers cited the founding positive psychologists directly and one paper cited them indirectly, through other citations. As the field grows, more and more research may cite the foundation studies indirectly, which may initially and unintentionally obfuscate established links to previous positive psychology research. Further, work may employ the term “positive psychology” but may not situate itself conceptually within established positive psychology research and theory. One theoretical paper excluded from the current review described positive emotions but did not address positive psychology explicitly in the body of the work, although “positive psychology” was indicated as a key word (Radziwillowicz & Szeliga, 2002). This may have occurred as a function of translation to English as the original work was written in Polish. Therefore, critical thinking, a thorough analysis of the nature and manner of citations, and precise descriptions of conceptual frameworks are necessary, especially at this early stage of the field.

The Application of Positive Psychology to the Addictions is a Multi-National Phenomenon

Thirty percent of the papers reviewed were of European origin. This reflects the international nature of positive psychology scholarship. It is likely that future contributions in this area will come from an international literature.

Positive Psychology offers a Framework from which to Study Addiction Recovery

Galanter (2007) writes, “the model of spiritually grounded recovery … emphasizes the achievement of meaningful or positive experiences, rather than a focus on observable, dysfunctional behaviors” (p. 266) and continues, “recovery can be understood as a process whereby an abstinent addicted person is moving toward a positive adaptation in life” (p. 266). These comments support the natural affiliation of the recovery movement and positive psychology. Applications of positive psychology to the recovery experience would further our understanding of successful recovery. The two dissertations on this topic in the current review were not, to our knowledge, later published in academic journals; however, peer-reviewed work on positive psychology and recovery is one area of scholarship that has potential for growth.

Initial work on Positive Interventions is Promising

The implications of the Akhtar and Boniwell (2010) study bear repeating. Their pilot of a positive intervention group with adolescents with substance use disorders was favorably reviewed by the participants who significantly outpaced the control group on a host of beneficial outcomes.

Future Research

Positive psychologists point out that “very little empirical research has explored the role of positive emotions and of strengths in prevention and treatment” (Duckworth, et al., 2005, p. 631). If this is true of prevention and intervention in general, it is especially true in addiction studies. The evidence-based positive interventions (Rashid, 2009; Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006; Seligman, et al., 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), and the group intervention for adolescents described in this review (Akhtar & Boniwell, 2010), have potential for further testing among individuals with substance use disorders.

Joseph and Wood (2010) have grappled with how to initiate positive psychology into traditional clinical psychology practice. They identified an important first step: to determine the extent to which current interventions in clinical psychology may already have a positive psychology component, without naming it as such. To what extent may substance use disorder “treatment-as-usual” already increase positive affect and build character strengths? A review of current evidence-based practices may show that integration is organically occurring.

Positive affect, optimism, hopefulness, emotional vitality, enjoyment of life, and other measures of psychological well-being have been shown to predict favorable outcomes in cases of heart disease, stroke, and mortality generally (Steptoe, 2010). Could positive psychology constructs be predictive of addiction treatment outcomes? Considering that individuals enter substance use treatment at the nadir of their lives, is it plausible that baseline measures of positive constructs would vary? If they do, could they predict outcomes? Research on the variability of positive psychology predictors at treatment entry is needed to better understand how individuals with addictive disorders are faring at that point, and whether these constructs have predictive power over later drinking or drug use.

Another potentially fruitful area of study would involve an analysis of motivational interviewing and positive psychology. To what degree are these movements conceptually and empirically similar? How can collaborations and integration of the two movements improve the lives of individuals who suffer from addictions? With reference to another recovery philosophy, how might positive psychology inform the study of natural recovery? Might positive psychology constructs predict the course of natural recovery?

Finally, there is significant potential for positive psychology to contribute to the work of the recovery movement, broadening and deepening its focus on depathologizing recovery from addictions. The recovery movement emphasizes recovery versus pathology and understands addiction as a chronic condition. However, recovery management and recovery-oriented systems of care paradigms may not fully honor this paradigm shift. For example, continuing care interventions, such as Recovery Management Checkups, adequately treat addiction as a chronic condition with a long-view to recovery but many still focus exclusively, or disproportionately, on pathology. McKay (2011) writes, “This emphasis in most continuing care treatments on addressing deficits is at odds to some degree with a more recovery-oriented approach, which focuses to a greater extent on identifying, nurturing, and further developing an individual’s skills, talents, and interests” (p. 170). McKay’s insight creates an opening for positive psychology principles, constructs, measures, and interventions to be applied to continuing care and other recovery movement initiatives.

Conclusion

Despite tremendous growth in both positive psychology and the recovery culture that has led to parallel social movements, as far as we are aware, only the work included in this review has thus far explicitly applied the discoveries of positive psychology to substance use, addiction treatment, and recovery. The search criteria employed in this review was broad, and yet only nine works met criteria for inclusion. This small number itself is illustrative of the state of the field. At a time when a search for “positive psychology” within amazon.com yields 948 hits and within Psycinfo yields 2554 hits, the current review suggests that the application of positive psychology to the addictions is a late entry to the positive psychology movement. However, late entry offers the benefit of building productively on previous research while heeding previous critiques. As noted, while the recovery movement employs the disease model of addiction, it has historically been an initiative for macro systemic change while positive psychology has historically promoted micro interventions designed to create change at the level of the individual. Thus, integration of the two movements can more comprehensively cover the micro-mezzo-macro continuum of care necessary to adequately address the costly social problem of addiction.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant number UL1RR024986 from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or the National Institutes of Health.

With special thanks to Fernando H. Andrade, Jaclyn C. Bradley, Kirk J. Brower, Daniel J. Clauw, James A. Cranford, Afton Hassett, Jakub Klimkiewicz, Fawn Landrum, Gregory Racz, Elizabeth A. R. Robinson, William L. White, and Yoav Ben Yosef. Thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful critiques and suggestions.

References

- Akhtar M, Boniwell I. Applying positive psychology to alcohol-misusing adolescents: A group intervention Groupwork: An Interdisciplinary. Journal for Working with Groups. 2010;20(3):6–31. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Former APA Presidents. n.d Retrieved August 8, 2011, from http://www.apa.org/about/governance/president/past-presidents.aspx.

- Arminen I. Closing of turns in the meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous: Member’s methods for closing ‘sharing experiences’. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2001;34(2):41. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Tedeschi RG. Of Babies and Bathwater: A Reply to Coyne and Tennen’s Views on Positive Psychology and Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010a;39(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Tedeschi RG. The Value of Positive Psychology for Health Psychology: Progress and Pitfalls in Examining the Relation of Positive Phenomena to Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010b;39(1):4–15. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Recovery Schools. Mission. n.d from http://www.recoveryschools.org/about_mission.html.

- Beauvais F, Oetting ER. Drugs use, resilience, and the myth of the golden child. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL, editors. Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Marecek J. Dreaming the American dream: Individualism and positive psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2(5):1767–1780. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00139.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin FC, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S. A comparison of a brief and long version of the Situational Confidence Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38(12):1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HP, Peterson JH. Rationale and procedural suggestions for defining and actualizing spiritual values in the treatment of dependency. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 1990;7(3):17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrocchi JW, Brelsford GM. Spirituality, religion, and substance copingas regulators of emotions and meaning making: Different effects on pain and joy. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling. 2009;30(1):24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Harris KS, Baker AK, Herbert R, Dean LR. Characteristics of a collegiate recovery community: Maintaining recovery in an abstinence-hostile environment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP, Wiersma JD. How Membership in the Collegiate Recovery Community Maximizes Social Support for Abstinence and Reduces Risk of Relapse. Substance Abuse Recovery in College: Community Supported Abstinence. 2010:97–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1767-6_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social Determinants of Alcohol-Consumption -the Effects of Social-Interaction and Model Status on the Self-Administration of Alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Tennen H. Positive Psychology in Cancer Care: Bad Science, Exaggerated Claims, and Unproven Medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39(1):16–26. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumbaugh JC, Maholick LT. An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1964;20(2):200–207. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(196404)20:2<200::aid-jclp2270200203>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperPerennial; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon G. The therapeutic community: theory, model, and method. New York: Springer Pub; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Delle Fave A, Massimini F. The investigation of optimal experience and apathy -Developmental and psychosocial implications. European Psychologist. 2005;10(4):264–274. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.10.4.264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. 4. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. What Is Positive About Positive Psychology: The Curmudgeon and Pollyana. Psychological Inquiry. 2010;14(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Steen TA, Seligman MEP. Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:629–651. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]