Abstract

We evaluated acute hematological and long-term pulmonary toxicity of radioimmunotherapy in murine models of Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Activities up to 250 μCi were well tolerated by healthy A/JCr mice for 213Bi-18B7 and 188Re-18B7 monoclonal antibodies. In infected mice, doses up to 150 μCi produced only transient toxicity. The lungs of treated mice had no evidence of radiation fibrosis.

Cryptococcus neoformans infection presents a serious therapeutic challenge in immunocompromised patients in whom antifungal therapy is not effective. It was recently demonstrated that treatment of C. neoformans-infected mice with a monoclonal antibody (MAb) to the capsular polysaccharide, labeled with either rhenium-188 (188Re) or bismuth-213 (213Bi), significantly prolonged the survival of lethally infected mice and reduced organ fungal burden (3). That study established a proof of principle for the usefulness of radioimmunotherapy (RIT) against an infection but invited questions about the safety of the approach. Here, we have evaluated the acute hematological and long-term pulmonary toxicity of RIT in murine models of C. neoformans infection.

To study the acute hematological toxicity of RIT, seven groups of five A/JCr female mice were infected intravenously with 105 C. neoformans cells. The intravenous infection results in rapid death of infected animals and is a standard model for antifungal susceptibility testing (7). Twenty-four hours after infection, groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 received intraperitoneal injections of 100, 150, 200, and 250 μCi of 213Bi-18B7 MAb, respectively; groups 5 and 6 received 100 and 200 μCi of 188Re-18B7, respectively; and group 7 was left untreated. The amount of cryptococcal polysaccharide-specific MAb 18B7 per injection was 30 to 50 μg, and the injection volume was 0.2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. Platelet counts were done to assay for potential bone marrow toxicity (6) on days 3, 7, and 14 posttreatment. To compare the hematological toxicity of this therapy in mice infected with C. neoformans and in healthy mice, eight groups of five healthy A/JCr mice were injected with 100, 150, 200, and 250 μCi of 213Bi-18B7 or 188Re-18B7 MAbs, with group 9 being left untreated, and the platelets were counted on days 3, 7, and 14 posttreatment. Student's t test for unpaired data was used to analyze differences in the number of platelets. Differences were considered statistically significant when P values were <0.05.

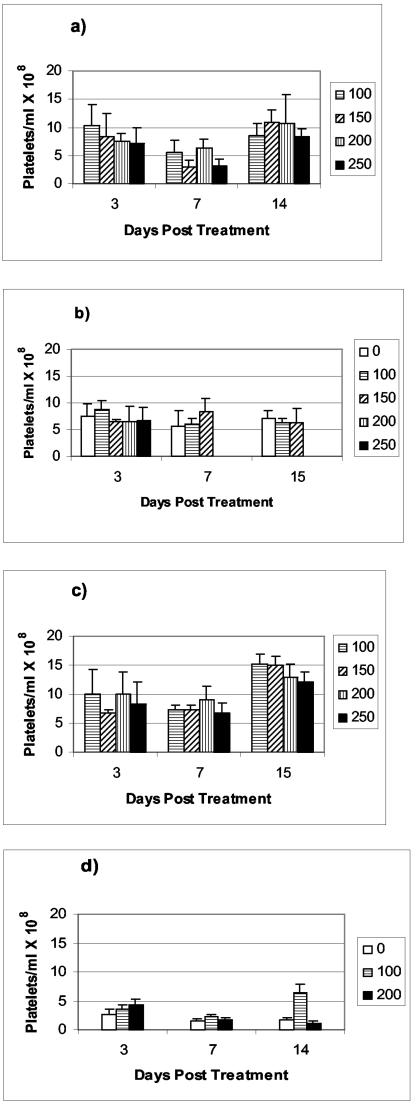

The serum platelet counts in healthy A/JCr mice and mice systemically infected with C. neoformans are presented in Fig. 1. Activities up to 250 μCi were well tolerated by healthy mice for both 213Bi-18B7 and 188Re-18B7 MAbs (Fig. 1a and c). A significant decrease in platelet counts was observed for all treatment groups at day 7 relative to untreated control mice and to the levels at day 3 (P < 0.01). This result is consistent with the reported nadirs in platelet and peripheral white blood cell counts, which are usually reached 1 week after radiolabeled antibody administration to tumor-bearing animals (1, 9). The platelet numbers recovered for all 213Bi-18B7- and 188Re-18B7-treated healthy animals on day 14. The tolerance of radiation was different when mice systemically infected with C. neoformans were treated with the same doses of radiolabeled MAb (Fig. 1b and d). For the 213Bi-18B7 treatment, the 200- and 250-μCi doses proved to be radiotoxic, with all mice in these two groups dying by day 7. However, doses of 100 and 150 μCi did not produce mortality and did not cause significant decreases in platelet counts (P = 0.07). For the 188Re-18B7-treated animals, the 200-μCi dose caused a significant drop in platelet counts (P = 0.02) at day 7, which did not normalize by day 14 and thus might attest to the possible radiotoxicity of this dose. The platelet number normalized by day 14 in mice treated with 100 μCi of 188Re-18B7, consistent with transient toxicity. These measurements parallel our previous results (3) on therapy of C. neoformans-infected A/JCr mice with 213Bi-18B7 and 188Re-18B7 MAbs, where administration of 100-μCi doses of 213Bi-18B7 and 188Re-18B7 MAbs resulted in most of the animals surviving while a 200-μCi dose was apparently too toxic and caused death of treated animals.

FIG. 1.

Platelet counts in A/JCr mice. Healthy mice (a and c) and C. neoformans-infected mice (b and d) received various doses of 213Bi-18B7 (a and b) or 188Re-18B7 (c and d). A “0” indicates infected nontreated mice. C. neoformans-infected mice treated with 200 and 250 μCi of 213Bi-18B7 (b) died by day 7 posttreatment. The platelet count in healthy nontreated A/JCr mice was (8.8 ± 2.4) × 108 platelets/ml.

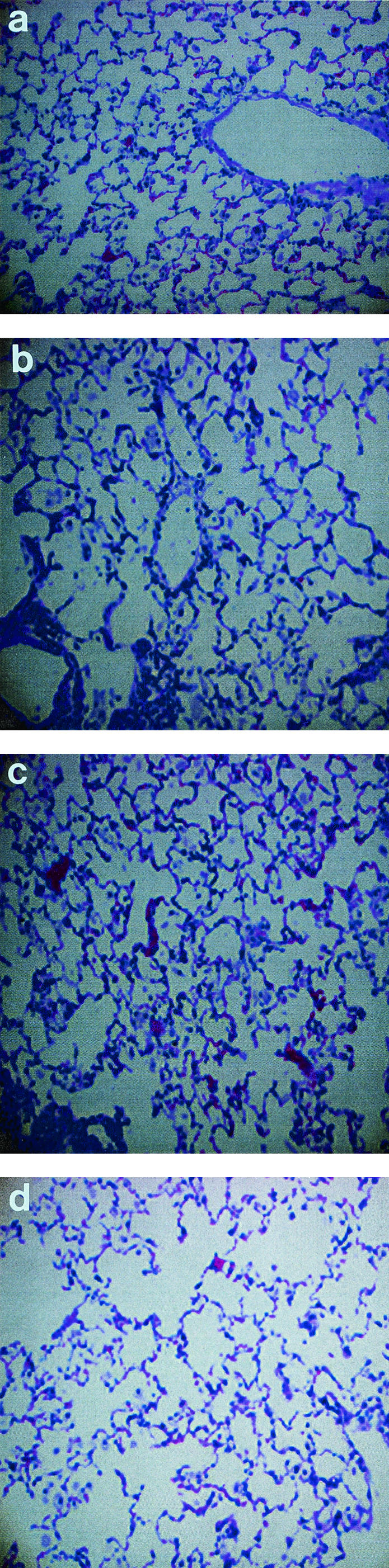

We considered the possibility that RIT may promote lung fibrosis in treated animals. Lungs are the target organ for C. neoformans infection and can develop fibrosis several months after treatment with external beam radiation therapy (5). To evaluate this potential complication we used a pulmonary model of C. neoformans where mice are infected intratracheally (IT). In this model, C. neoformans is mostly localized to the lungs on day 5 postinfection, and as a result up 10% of the injected dose/g is found in the lungs at 24 h after treatment with radiolabeled MAbs, versus 1.5% of the injected dose/g in the lungs of systemically infected mice (3). Eight groups of five BALB/c mice were infected IT with 106 C. neoformans, and on day 5 postinfection, groups 1, 2, and 3 were treated with 50, 100, and 200 μCi of 213Bi-18B7 MAb, respectively; groups 4, 5, and 6 were treated with the same activities of 188Re-18B7, respectively, while groups 7 and 8 were left untreated. All mice were subsequently maintained on fluconazole to control infection (10 mg/kg in their drinking water). After 5 months the mice were sacrificed, and their lungs were removed, fixed with buffered formalin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and analyzed histologically. There was no evidence of radiation fibrosis in the lungs of radiation-treated mice compared to control animals (Fig. 2). The absence of fibrosis can be explained by the relatively low doses of particulate radiation delivered by radiolabeled antibodies to the sites of the infection during RIT—the doses are in the range of 2.5 to 5 Gy (∼0.1 to 0.2 Gy/h) (2). For comparison, high-dose radiation, which is typical for external beam radiation therapy, delivers 60 Gy/h (8).

FIG. 2.

Micrographs of hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained lungs from BALB/c mice infected IT with C. neoformans and treated with radiolabeled antibodies. Mice were sacrificed 5 months after RIT. (a) Infected control for Bi group (no RIT); (b) 200 μCi of 213Bi-18B7; (c) infected control for Re group (no RIT); (c) 200 μCi of 188Re-18B7.

Important determinants of the extent and duration of myelosuppression following RIT in cancer patients include bone marrow reserve (based on prior cytotoxic therapy and extent of disease involvement), total tumor burden, spleen size, and radioimmunoconjugate stability (4). Clearly, the application of RIT to human cryptococcosis or other infectious diseases will require optimization of the dose to minimize toxicity. However, we are encouraged that these initial studies in mice suggest that RIT for infection is relatively well tolerated and may have a significantly higher therapeutic index than RIT for cancer. The results suggest a relatively high margin of safety for this novel antimicrobial therapy.

Acknowledgments

Actinium-225 for construction of a 225Ac/213Bi generator was obtained from the Institute for Transuranium Elements, Heidelberg, Germany.

The research was in part supported by NIH grants AI52042 (E.D.), AI52733 (J.D.N.), and AI033774 (A.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Behr, T. M., M. Behe, M. G. Stabin, E. Wehrmann, C. Apostolidis, R. Molinet, F. Strutz, A. Fayyazi, E. Wieland, S. Gratz, L. Koch, D. M. Goldenberg, and W. Becker. 1999. High-linear energy transfer (LET) alpha versus low-LET beta emitters in radioimmunotherapy of solid tumors: therapeutic efficacy and dose-limiting toxicity of 213Bi- versus 90Y-labeled CO17-1A Fab′ fragments in a human colonic cancer model. Cancer Res. 59:2635-2643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dadachova, E., R. W. Howell, R. A. Bryan, A. Frenkel, J. D. Nosanchuk, and A. Casadevall. Susceptibility of human pathogens Cryptococcus neoformans and Histoplasma capsulatum to gamma radiation versus radioimmunotherapy with alpha- and beta-emitting radioisotopes. J. Nucl. Med., in press. [PubMed]

- 3.Dadachova, E., A. Nakouzi, R. A. Bryan, and A. Casadevall. 2003. Ionizing radiation delivered by specific antibody is therapeutic against a fungal infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:10942-10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knox, S. J., and R. F. Meredith. 2000. Clinical radioimmunotherapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 10:73-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koenig, T. R., R. F. Munden, J. J. Erasmus, B. S. Sabloff, G. W. Gladish, R. Komaki, and C. W. Stevens. 2002. Radiation injury of the lung after three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy. Am. J. Roentgenol. 178:1383-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miale, J. B. 1982. Laboratory medicine hematology, p. 864. The CV Mosby Company, St. Louis, Mo.

- 7.Mukherjee, J., L. S. Zuckier, M. D. Scharff, and A Casadevall. 1994. Therapeutic efficacy of monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan alone and in combination with amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:580-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murtha, A. D. 2000. Review of low-dose-rate radiobiology for clinicians. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 10:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharkey, R. M., R. D. Blumenthal, T. M. Behr, G. Y. Wong, L. Haywood, D. Forman, G. L. Griffiths, and D. M. Goldenberg. 1997. Selection of radioimmunoconjugates for the therapy of well-established or micrometastatic colon carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 72:477-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]