Abstract

Objectives

Little is known about how opioid prescriptions for chronic pain are initiated. We sought to describe patterns of prescription opioid initiation, identify correlates of opioid initiation, and examine correlates of receipt of chronic opioid therapy (COT) among veterans with persistent non-cancer pain.

Methods

Using Veterans Affairs (VA) administrative data, we identified 5,961 veterans from the Pacific Northwest with persistent elevated pain intensity scores who had not been prescribed opioids in the prior 12 months. We compared veterans not prescribed opioids over the subsequent 12 months to those prescribed any opioid and to those prescribed COT (≥90 consecutive days).

Results

During the study year, 34% of the sample received an opioid prescription, and 5% received COT. Most first opioid prescriptions were written by primary care clinicians. Veterans prescribed COT were younger, had greater pain intensity, and high rates of psychiatric and substance use disorders (SUDs) compared to veterans in the other two groups. Among patients receiving COT, 29% were prescribed long-acting opioids, 37% received one or more urine drug screens, and 24% were prescribed benzodiazepines. Adjusting for age, sex, and baseline pain intensity, major depression (OR 1.24 [1.10–1.39]; 1.48 [1.14–1.93]) and nicotine dependence (1.34 [1.17–1.53]; 2.02 [1.53–2.67]) were associated with receiving any opioid prescription and with COT, respectively.

Discussion

Opioid initiations are common among veterans with persistent pain, but most veterans are not prescribed opioids long-term. Psychiatric disorders and SUDs are associated with receiving COT. Many Veterans receiving COT are concurrently prescribed benzodiazepines and many do not receive urine drug screening; additional study regarding practices that optimize safety of COT in this population is indicated.

Keywords: Chronic pain, Opioids, Veteran

Introduction

Chronic non-cancer pain may occur in up to half of patients treated in primary care settings, including veterans 1–3. Opioids are the most commonly utilized prescription medication for treatment of chronic pain 4, and in the past few decades, the use of opioids for chronic pain has increased dramatically. Unfortunately, there is little empirical information to guide clinicians regarding when to initiate or to continue opioids for their patients with chronic pain. Organizations have made efforts to develop chronic pain and opioid treatment guidelines 5–7. These guidelines advocate for conducting careful assessments, using opioids after other modalities have been tried, and/or as part of a multi-modal treatment plan, informing patients of risks and benefits of using opioids, taking extra precautions for patients at high risk for aberrant medication-related behaviors, and monitoring outcomes. Nonetheless, the efficacy and safety of long-term opioid therapy remains unclear 8–9.

In addition, little is known about the circumstances of opioid initiations for chronic pain, in particular, which clinicians initiate them and under what clinical circumstances. Some research has examined predictors of initiating and continuing prescription opioids, principally with non-VA patient populations, and has shown that important predictors include comorbid psychiatric disorders, problem drug use, and nicotine use 10–13. A more recent examination of opioid prescription patterns from a large managed care plan in NW Oregon and SW Washington found that psychological distress, unhealthy lifestyles, and healthcare utilization were incrementally associated with duration of prescription opioids 14. In two recent studies of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) Veterans treated in the VA healthcare system, prevalent prescription opioid use was common and associated with psychiatric and nicotine use disorders 15–16. In these latter studies, use of concurrent sedative hypnotics was common, multiple prescribers were often involved, and urine drug screening was administered infrequently, suggesting that many of these patients may not be receiving optimal chronic pain care 7, 17. However, information about incident opioid prescribing was not available in these recent studies.

The objectives of the current study were to 1) describe patterns of prescription opioid initiation, 2) identify correlates of prescription opioid initiation, and 3) identify correlates of chronic opioid therapy (>90 consecutive days) use among Veterans with persistent non-cancer pain who received care in a VA regional healthcare network.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the local VA Medical Center.

Subjects

Potential subjects were veterans who received any medical care at VA facilities (Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN]-20) in the Pacific Northwest (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska) during calendar year 2008. Patient data were extracted from the VISN-20 Data Warehouse, which is updated regularly and contains data from the main clinical software packages of regional VA healthcare facilities and two national VA databases 18. Patients with pain were identified using pain numeric rating scores (NRS) that were obtained as part of routine screening; over 95% of veterans with an outpatient visit in VISN-20 in 2008 had at least one NRS score. The NRS rates pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst possible pain 19. We selected patients who had NRS pain scores ≥4 recorded in at least three different months during 2008, consistent with common definitions of chronic or persistent pain that require at least three to six month duration of moderate to severe pain 20. A cutoff of four was used for this study due to its consistency with VA clinical practice and policy regarding indication for further evaluation of pain. Scores of four are also indicative of moderate to severe pain 7, 21. An index date was calculated for each subject, defined as the date of the last pain score ≥4 in calendar year 2008.

We identified a total of 24,130 veterans in VISN-20 who met our definition for having persistent pain in 2008. After excluding patients with cancer diagnoses (n=4,788), surgery (n=1,298), or participation in a VA opioid substitution programs (n=408) in the year prior to or during the 12-month study period, as well as veterans who died during the study year (n=510), we were left with 17,126 patients with persistent pain. Of these, 5,961 (35%) had not been prescribed any opioid by a VISN-20 clinician in the 12 months prior to the 2008 index date. Patients who were subsequently prescribed opioids during the 12-month study period following the index date were classified into two groups: patients prescribed opioid medications on a short-term basis (<90 days) (n=1,767) or patients prescribed opioid medications for 90 or more consecutive days (COT) (n=273). Ninety or more consecutive days has been used as an indicator of COT in previous studies 22,23. Prescriptions for tramadol or buprenorphine were excluded from the study because tramadol has weak opioid activity and in clinical practice is sometimes prescribed for reasons other than treatment of pain; buprenorphine is not FDA approved for the treatment of pain.

Demographic data included age, sex, race, marital status, and VA service-connected disability status. Diagnoses of common psychiatric and substance use disorders (including alcohol abuse/dependence) made by clinicians during healthcare contacts were collected for the 12 months prior to the index date. Inpatient and outpatient diagnoses were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification – 9th Revision. These diagnoses were also used to calculate a Charlson Comorbidity score, a measure of the overall burden of medical conditions 24. Body mass index (BMI) was computed based on height and weight data obtained in proximity to the time of the index date. VA pharmacy data were collected for the 12 months after the index date to obtain information on prescriptions of current opioids as well as non-opioid analgesics. Each opioid prescription dose was converted to a morphine equivalent dose 25. We also collected data on administrations of urine drug screens. The lists of ICD-9-CM codes utilized and specific medications examined in this study may be obtained upon request from the first author.

Statistical Analyses

Patients who were prescribed COT were compared to patients who were prescribed opioids for fewer than 90 days (short-term use) and to patients who did not receive an opioid prescription over the study period. Demographic and diagnostic data were analyzed with chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate demographic and clinical variables associated with receiving an opioid prescription. These analyses controlled for the effects of age, sex, and baseline pain intensity. Other variables that were entered into the models included diagnoses of major depressive disorder, nicotine dependence, and any substance use disorder (excluding caffeine and nicotine). Variables were included based on the results from the bivariate tests and relationships shown or suggested by prior literature. In some instances, we excluded diagnoses that may be associated with an increased likelihood of receiving a prescription because of a high degree of correlation with variables already included in the model (e.g., PTSD was not included because of its strong correlation with major depressive disorder). In the first model, we evaluated the likelihood of receiving any opioid prescription. For this model, COT and short-term groups were collapsed, and the reference group was comprised of patients who did not receive an opioid prescription. In the second model, we examined factors associated with receiving prescriptions for COT. The reference group was patients who did not receive an opioid prescription and in this model, we did not include patients who received short-term opioid prescriptions.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The majority of the sample was male (90%) and white (86%), and the average age was 56. Of the 5,961 patients in the sample, 1767 (30%) were prescribed opioids on a short-term (<90 days) basis, and 273 (4.6%) were prescribed COT (≥90 days) over the 12-month study period (Table 1). Patients not prescribed opioids were slightly older than patients prescribed opioids (p<0.001). COT patients were less likely to be married than patients receiving only short term or no opioids. (p=0.007). Otherwise, no significant demographic differences were detected when comparing patients prescribed opioids and patients not prescribed opioids.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Study Group

| No Opioid (n=3921) |

Short-term use (n=1767) |

COT (n=273) |

Test (df) |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (sd) | 56.8 (13.4) | 55.5 (13.3) | 54.6 (13.7) | F (2,5960)=7.9 | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 3473 (88.6) | 1547 (87.5) | 255 (93.4) | χ2 (2) = 8.0 | 0.018 |

| Marital Status, n (%) | χ2(2) = 21.2 | 0.007 | |||

| Single/Never Married | 467 (11.9) | 234 (13.2) | 46 (16.8) | ||

| Married | 1955 (49.9) | 836 (47.3) | 116 (42.5) | ||

| Separated/Divorced | 1178 (30.0) | 566 (32.0) | 83 (30.4) | ||

| Widow | 199 (5.1) | 95 (5.4) | 22 (8.1) | ||

| Unknown | 122 (3.1) | 36 (2.0) | 6 (2.2) | ||

| Race, n (%) | χ2(2) = 12.1 | 0.59 | |||

| White | 2607 (66.5) | 1192 (67.5) | 194 (71.1) | ||

| Black | 297 (7.6) | 164 (9.3) | 14 (5.1) | ||

| Other | 173 (4.4) | 73 (4.1) | 10 (3.7) | ||

| Unknown or Declined | 844 (21.5) | 338 (19.1) | 55 (20.1) |

Note. COT = Chronic opioid therapy: ≥90 consecutive days of an opioid prescription during study year.

Table 2 compares clinical pain variables and diagnoses among the three groups. The average number of days prescribed opioids in one year was 37.4 days (SD=39.7) for patients prescribed opioids short-term compared to 234.3 days (SD=75.5) for patients prescribed COT. Rates of pain diagnoses significantly differed between the three groups on all disorders assessed, except fibromyalgia, inflammatory bowel disease, and neuropathy. The COT group was more likely to be diagnosed with every pain condition assessed. The prevalence of nicotine use disorder was significantly greater in the COT group compared to the other two groups. Similarly, rates of mental disorder diagnoses were significantly higher in the COT group for major depressive disorder, PTSD, substance use disorder (which included alcohol abuse/dependence), and sleep disorders. The Charlson Comorbidity Score was higher in the COT group and the short-term use group compared to the non-opioid users (p<0.001). Patients prescribed COT also had a greater average reported pain intensity at their index dates compared to patients prescribed opioids short-term or patients not prescribed opioids (p=0.01).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics by Study Group

| No Opioid (n=3921) |

Short-term use (n=1767) |

COTa (n=273) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Diagnoses | ||||

| Fibromyalgia, n (%) | 148 (3.8) | 79 (4.5) | 10 (3.7) | 0.445 |

| Inflamm. Bowel Disease, n (%) | 69 (1.8) | 36 (2.0) | 3 (1.1) | 0.510 |

| Low Back Pain, n (%) | 1567 (40.0) | 729 (41.3) | 135 (49.5) | 0.008 |

| Migraine Headache, n (%) | 299 (7.6) | 170 (9.6) | 26 (9.5) | 0.031 |

| Neck or Joint Pain, n (%) | 1961 (50.0) | 995 (56.3) | 152 (55.7) | < 0.001 |

| Neuropathy, n (%) | 252 (6.4) | 110 (6.2) | 20 (7.3) | 0.785 |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 1512 (38.6) | 744 (42.1) | 124 (45.4) | 0.007 |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses | ||||

| Major Depressive Disorder, n (%) | 1297 (33.1%) | 641 (31.2%) | 117 (42.9%) | 0.001 |

| Dysthymic Disorder, n (%) | 214 (5.5%) | 101 (5.7%) | 17 (6.2%) | 0.823 |

| Bipolar Disorder, n (%) | 237 (6.0%) | 102 (5.8%) | 26 (9.5%) | 0.052 |

| Panic Disorder, n (%) | 77 (2.0%) | 45 (2.5%) | 8 (2.9%) | 0.260 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, n (%) | 981 (25.0%) | 495 (28.0%) | 84 (30.8%) | 0.012 |

| Other Anxiety Disorder, n (%) | 414 (10.6%) | 214 (12.1%) | 36 (13.2%) | 0.124 |

| Schizophrenia, n (%) | 169 (4.3%) | 56 (3.2%) | 8 (2.9%) | 0.084 |

| Sleep Disorder, n (%) | 316 (8.1%) | 173 (9.8%) | 32 (11.7%) | 0.021 |

| Substance use Disorder, n (%) | 641 (16.3%) | 338 (19.1%) | 78 (28.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Nicotine Disorder, n (%) | 915 (23.3%) | 445 (25.2%) | 102 (37.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Mean Body Mass Index, n (sd) | 31.5 (7.1) | 31.4 (7.0) | 30.5 (6.8) | 0.171 |

| Mean Pain Intensity Scoreb,(sd) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4.9 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.9) | 0.010 |

| Mean Charlson Comorbidity Score,(sd) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.5) | 0.028 |

Note.

COT = Chronic opioid therapy: ≥90 consecutive days of an opioid prescription during study year.

Pain is rated on a scale of 0 to 10 Numerical Rating System, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst possible pain.

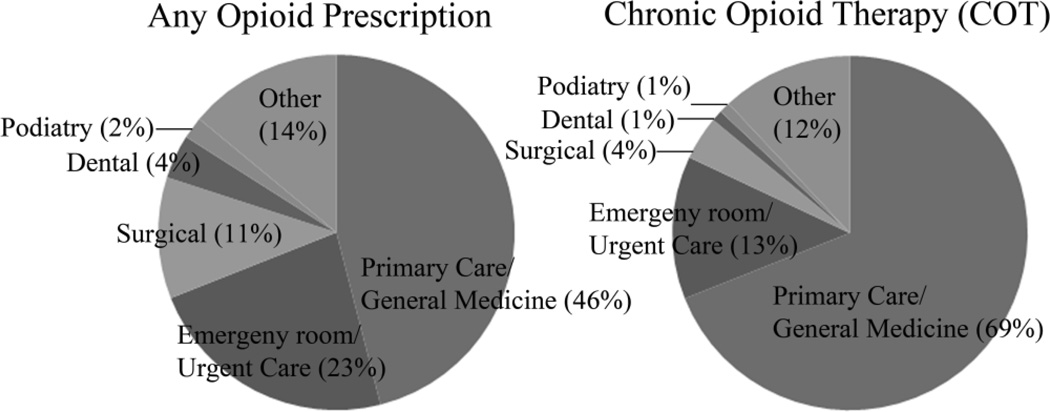

We examined the source of first opioid prescriptions among patients receiving opioid prescriptions (Figure 1). Among those with any opioid prescription, 46/2040 (2%) had their first opioid prescriptions written during the study period while inpatients, and within the COT group, 3/273 (1%) had them written while they were inpatients. Forty-six percent of patients who received any opioid received their first outpatient prescription from primary care clinicians, whereas 69% of COT patients received their first outpatient prescriptions from primary care clinicians. Emergency room clinicians were the second most common source of initial prescriptions for patients receiving any opioid (23%), and for patients receiving COT (13%).

Figure 1.

Setting for First Outpatient Opioid Prescription

Among the patients who received any opioid prescription, patients receiving only short-term prescriptions received slightly lower average daily morphine equivalent doses than those who received COT (23.1 mg [SD=22.2] vs. 26.4 mg [SD=22.1]; p=0.026). The range of average morphine equivalent dose for acute users was 2.5 mg to 167 mg per day compared to 4 mg to 174 mg per day for COT users. The most commonly prescribed opioid for both groups was hydrocodone followed by oxycodone (Table 3). The majority of short-term users were prescribed a short-acting opioid (98.2%) and few short-term users were prescribed a long-acting opioid (5.7%). Among patients receiving COT, 93% were prescribed at least one short-acting opioid while 29.3% were prescribed at least one long-acting opioid. Patients receiving COT were more likely to be prescribed a combination of a short-acting and long-acting opioid (22.3% versus 3.9%, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Types of opioid medications prescribeda

| Short-term use |

COTa | Test (df) |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Acting Opioids | 1736 (98.2%) | 254 (93.0%) | χ2(1)=26.8 | < 0.001 |

| Hydrocodone | 1205 (68.2%) | 199 (72.9%) | ||

| Oxycodone | 465 (26.3%) | 101 (37.0%) | ||

| Codeine Sulfate | 291 (16.5%) | 24 (8.8%) | ||

| Hydromorphone | 19 (1.1%) | 7 (2.6%) | ||

| Morphine Sulfate | 17 (1.0%) | 13 (4.8%) | ||

| Long-Acting Opioids | 100 (5.7%) | 80 (29.3%) | χ2(1)=164.3 | < 0.001 |

| Methadone | 43 (2.4%) | 47 (17.2%) | ||

| Morphine Sulfate (long acting) | 55 (3.1%) | 45 (16.5%) | ||

| Fentanyl | 6 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) | ||

| Oxycodone (long-acting) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 |

Note.

Any prescription over the study year

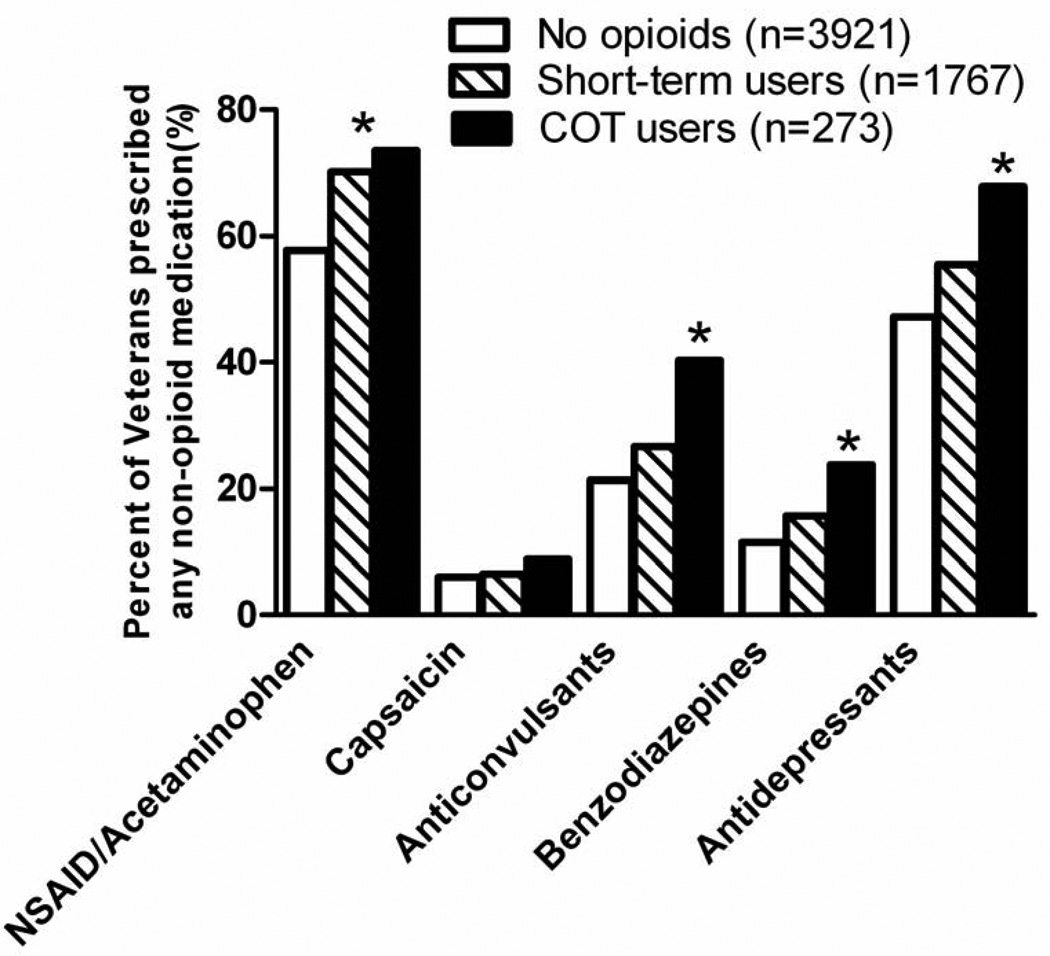

The proportions of CNCP patients receiving various non-opioid but often-used medications for pain are shown in Figure 2. Short-term opioid and COT patients were prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen more frequently than non-opioid users. Anticonvulsants and antidepressants were more frequently prescribed to COT patients compared to short-term users and non-opioid users. Benzodiazepine prescriptions were prescribed more frequently to COT patients than to short-term and non-opioid patients (23.8% versus 15.7% and 11.5%, χ2 (2) = 46.5, p< 0.001). There was an increased frequency of urine drug screens administered to COT patients (37%) compared to patients prescribed opioids short-term (23%), or patients not prescribed opioids (16%) (χ2 (2) = 96.8; p<0.001). Among patients who had at least one urine drug screen, there was no difference between groups in the likelihood of having a positive screen for illicit substances (9% versus 5% and 8%, χ2 (2) = 3.3, p = 0.19).

Figure 2.

Tables 4 and 5 display the results of the logistic regression analyses examining factors associated with receipt of opioid prescriptions over the study period. In the first model, after adjusting for age, sex, and baseline pain intensity score, previous year diagnosis of substance disorder (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.03–1.38) and diagnosis of major depressive disorder (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.00–1.26) were significantly associated with greater odds of being prescribed any opioid over the study period. In the second model, which evaluated the likelihood of receiving COT, being male (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.11–3.05), baseline pain intensity scores (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.03–1.19), and diagnoses of nicotine dependence (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.21–2.10), substance use disorder (OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.09–2.02), and major depressive disorder (OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.04–1.75) were each associated with greater odds of receiving COT.

Table 4.

Odds of being prescribed any opioid over the study period (n=5,961)

| Beta (Standard Error) |

Wald | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01 (.01) | 7.5 | 0.006 | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) |

| Male | 0.02 (.09) | 0.1 | 0.835 | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) |

| Pain Intensity | 0.01 (.02) | 0.8 | 0.374 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 0.12 (.06) | 4.0 | 0.047 | 1.13 (1.00–1.26) |

| Nicotine Dependence | 0.10 (.07) | 2.3 | 0.134 | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) |

| Any Substance Use Disorder | 0.18 (.08) | 5.2 | 0.023 | 1.19 (1.03–1.38) |

Note. Reference group = No opioid prescriptions.

Table 5.

Odds of being prescribed chronic opioid therapy (>90 days) over the study period (n=4,194)*

| Beta (Standard Error) |

Wald | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.01 (.01) | 2.8 | 0.092 | 0.99 (0.98–61.00) |

| Male | 0.61 (.26) | 5.7 | 0.017 | 1.84 (1.11–3.05) |

| Pain Intensity | 0.10 (.04) | 8.2 | 0.004 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 0.30 (.13) | 5.1 | 0.025 | 1.35 (1.04–1.75) |

| Nicotine Dependence | 0.47 (.14) | 10.9 | 0.001 | 1.59 (1.21–2.10) |

| Any Substance Use Disorder | 0.40 (.16) | 6.3 | 0.012 | 1.49 (1.09–2.02) |

Note. Reference group = No opioid prescriptions.

short-term users excluded from this analysis.

Discussion

We found that about one-third of the veterans with persistent pain who were not prescribed opioids in 2008 received one or more opioid prescriptions in the subsequent 12 months. Most initial opioid prescriptions were written by primary care clinicians. In adjusted models, diagnoses of substance use disorder and major depression were associated with receiving any opioid prescription. Only 5% of patients with persistent pain went on to receive COT. Male sex, greater baseline pain intensity, nicotine dependence, substance use disorder, and major depression diagnoses were associated with COT initiations. Of the patients prescribed COT, fewer than one-third were prescribed long-acting opioids, one-third were administered one or more urine drug screens, and one-quarter were prescribed benzodiazepines.

Our results are generally consistent with prior studies of primarily non-VA patient populations showing that prescription opioid use is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders including substance use disorders and nicotine 10, 26, 27, 13, 28, 11, 15, 16. This is noteworthy considering that chronic pain treatment guidelines emphasize the need to exercise special caution when treating patients with SUD. An additional study 12 showed that patients with painful lumbar spine conditions self-reported 12-month incident prescribing rates of 8%, and another study 29 conducted at two large Pacific Northwest health plans showing one-year incident rates of long-term prescription opioid use (defined similarly as in our study) ranged from 6.3 to 12.1 per 1000. While the rates of incident prescribing found in these latter studies are lower than the rates we found, we utilized a study sample whose members had moderate to severe persistent pain at baseline as opposed to a sample of patients who may or may not have had pain at baseline.

The mechanisms underlying the relationship between psychiatric disorders and prescription opioid use are not clear. Mental disorders have been associated with a higher prevalence of various somatic symptoms including pain 30, and it is possible that in some cases opioids are used to treat poorly differentiated constellations of pain and emotional symptoms 31. Indeed, Turk and Okifuji 32 found, in a study of 191 patients from a multidisciplinary pain facility, that patients’ nonverbal communications of pain, distress and suffering were the primary predictors of physician opioid prescribing behavior. Furthermore, while the relationship between nicotine and pain and prescription opioid use has been well documented, the mechanisms underlying this relationship are not clear. Nicotine may be a marker for substance use disorder or other psychiatric disorder, or there may be alterations in pain processing due to exposure to chronic cigarette smoke and nicotine’s analgesic properties resulting in cross-tolerance with opioids 33. In our study we found that nicotine dependence remained significantly associated with opioid prescription in a model including substance use disorder and major depression, suggesting that nicotine use may have an independent effect on opioid initiation.

We found mixed results regarding the extent to which patients initiating opioids receive care that is optimally safe and effective. Pain treatment guidelines frequently recommend, in coordination with clinical judgment, that when pain is persistent long-acting opioids be considered to minimize the use of concurrent sedative-hypnotics, and to utilize urine drug screening for selected patients6, 34. Possible theoretical advantages of long-acting opioids include more stable opioid levels, increased tolerance to adverse effects, and reduced reinforcement of pain behaviors35. Yet there is little empiric evidence to support the use of long-acting over short-acting opioids36, and clinicians may consider this lack of evidence when prescribing opioids. In our sample, 29% of patients prescribed COT received a long-acting opioid. Furthermore, 24% of patients prescribed COT received concomitant benzodiazepine medications, which is concerning given that overdose deaths (including those related to opioids) have been linked to the use of multiple sedating medications37–39.

We also found the rate of urine drug screening to be relatively low. It has been suggested that patients have urine drug screening prior to opioid initiation and receive regular monitoring. Certainly, patients considered “high risk” should receive urine drug screening more frequently. While this concept of risk has not been well-defined, given the high rate of comorbid substance use disorders among patients with chronic pain 40, and that 29% of patients in the current sample receiving COT were diagnosed with a substance use disorder, these data support previous work demonstrating that urine drug screening is underutilized 41–43. Finally, patients who received opioids were more likely to receive adjuvant pain medications. While this is consistent with recommendations that opioids be used as one part of a comprehensive plan containing non-medication and non-opioid medication components, it may also reflect the medical and psychiatric complexity of patients who may be refractory to, or who have had multiple trials of, non-opioid pain treatment.

We found that although slightly less than half of opioid prescriptions used short-term were written by primary care providers, two-thirds of opioid prescriptions resulting in COT were initiated by primary care providers. This is important because pain treatment guidelines often advise that opioids be initiated only after trials of non-opioid medications, as part of a comprehensive pain treatment strategy, and framed as a trial dependent on monitoring outcomes over time 6, 34. While this treatment approach may be feasible in primary care settings, it would be less practical if most opioid prescriptions were started in emergency rooms or inpatient settings. The finding that opioids are primarily initiated in primary care supports the development of guidelines geared toward primary care practice. It also supports the feasibility of providing interventions and structures in primary care that facilitate proactive planning around opioid use and its monitoring.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. This was a retrospective study using administrative data. Participants were predominantly male, white veterans receiving VA healthcare in the Pacific Northwest portion of the U.S.; generalizability to patients in other regions or outside of the VA may be limited. Our findings are dependent on the extent, accuracy and validity of the data available in the VA administrative dataset. For example, because prescription medication information was obtained from administrative data, we were not able to evaluate patient adherence to prescribed medications. It is also difficult to distinguish between the use of two medications simultaneously versus concurrent use of two medications, and we could not determine the reasons particular adjunctive medications (e.g., antidepressants) were prescribed. It is also possible that the group of veterans who did not receive opioids in the full year prior to the index date were different from other patients who would otherwise have received opioids earlier in their pain care—perhaps this group of Veterans was more likely to be opioid averse. This could help to explain why the COT initiation rate was only 5% over the study period. An alternative method of examining factors associated with opioid initiations would be to examine incident prescribing among the larger group of veterans, not just those with persistent pain. Patients may have received opioids from a non-VA provider, which would not be detectable in these analyses. Finally, we did not assess the use of non-pharmacological treatments for pain, which may have been associated with opioid prescribing patterns and have clinical implications.

Conclusion

Relatively few veterans treated in the VA who have persistent pain and who are not prescribed opioids subsequently receive COT over a one-year period. Clinical factors associated with initiating COT include increased pain intensity, nicotine dependence, SUD, and major depression diagnoses. Most COT is initiated by primary care clinicians. Efforts to study and increase the safety and effectiveness of COT are indicated, as many patients are not receiving urine drug screening or may be concurrently prescribed benzodiazepines, which may place them at high risk for adverse consequences. Specifically, our findings suggest the value of clinicians conducting thorough assessments for important comorbidities such as depression and substance use disorder, and conducting ongoing monitoring of pain-related outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments/Sources of Support: This work was supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Portland VA Medical Center. Dr. Morasco received support from award K23DA023467 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Jonathan Duckart, MPS, was supported by grant REA 06-174 from the VA Health Services Research and Development service.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerns RD, Otis J, Rosenberg R, Reid MC. Veterans' reports of pain and associations with ratings of health, health-risk behaviors, affective distress, and use of the healthcare system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003 Sep-Oct;40(5):371–379. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.09.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: Results from the Veterans Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark JD. Chronic pain prevalence and analgesic prescribing in a general medical population. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002 Feb;23(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turk DC. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2002 Nov-Dec;18(6):355–365. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL. A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997–2002. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004 Aug;28(2):176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou R. 2009 Clinical Guidelines from the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine on the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: What are the key messages for clinical practice? Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009 Jul-Aug;119(7–8):469–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. 2010 http://www.healthquality.va.gov/Chronic_Opioid_Therapy_COT.asp.

- 8.Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain. 2004 Dec;112(3):372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martell BA, O'Connor PG, Kerns RD, et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jan 16;146(2):116–127. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166(19):2087–2093. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breckenridge J, Clark JD. Patient characteristics associated with opioid versus nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug management of chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2003 Aug;4(6):344–350. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00638-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krebs EE, Lurie JD, Fanciullo G, et al. Predictors of long-term opioid use among patients with painful lumbar spine conditions. J Pain. 2010 Jan;11(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP, Sullivan MD. Epidemiology of regular prescribed opioid use: results from a national, population-based survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008 Sep;36(3):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deyo RA, Smith D, Johnson ES, et al. Opioids for Patients with Back Pain in Primary Care: Prescribing Patterns and Use of Services. J Am Board Family Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.100232. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu PC, Lang C, Hasson NK, Linder SH, Clark DJ. Opioid use in young veterans. J Opioid Manag. 2010 Mar-Apr;6(2):133–139. doi: 10.5055/jom.2010.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macey TA, Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Dobscha SK. Patterns and Correlates of Prescription Opioid Use in OEF/OIF Veterans with Chronic Noncancer Pain. Pain Med. 2011 Oct;12(10):1502–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department Of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Integrated Service Network-20 Data Warehouse. http://moss.v20.med.va.gov/v20dw/default.aspx.3, 3/28/11.

- 19.Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986 Oct;27(1):117–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of chronic pain. Pain. 1986;(Supplement 3):S1–S225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleeland CS, Reyes-Gibby CC, Schall M, et al. Rapid improvement in pain management: the Veterans Health Administration and the institute for healthcare improvement collaborative. Clin J Pain. 2003 Sep-Oct;19(5):298–305. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edlund MJ, Sullivan M, Steffick D, Harris KM, Wells KB. Do users of regularly prescribed opioids have higher rates of substance use problems than nonusers? Pain Med. 2007 Nov-Dec;8(8):647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Korff M, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, et al. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2008 Jul-Aug;24(6):521–527. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318169d03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morasco BJ, Corson K, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Association between substance use disorder status and pain-related function following 12 months of treatment in primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. J Pain. 2011 Mar;12(3):352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007 Jun;129(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010 Jan;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b99f35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Unutzer J. Regular use of prescribed opioids: association with common psychiatric disorders. Pain. 2005 Dec 15;119(1–3):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 Dec;18(12):1166–1175. doi: 10.1002/pds.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Lee S, et al. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain. 2007 Jun;129(3):332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan M, Katon W. Somatization: The path between distress and somatic symptoms. Am Pain Soc J. 1993;2:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turk DC, Okifuji A. What factors affect physicians' decisions to prescribe opioids for chronic noncancer pain patients? Clin J Pain. 1997 Dec;13(4):330–336. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Y, Weingarten TN, Mantilla CB, Hooten WM, Warner DO. Smoking and pain: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology. 2010 Oct;113(4):977–992. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ebdaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VA/DoD. Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Washington, DC: VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline Working Group, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs and Health Affairs, Department of Defense (DoD) Office of Quality and Performance publication, Version 2.0. 2010. May, [Accessed August 11, 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Von Korff M, Merrill JO, Rutter CM, Sullivan M, Campbell CI, Weisner C. Time-scheduled vs. pain-contingent opioid dosing in chronic opioid therapy. Pain. 2011 Jun;152(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou R, Clark E, Helfand M. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting oral opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003 Nov;26(5):1026–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Apr 11;171(7):686–691. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Jan 19;152(2):85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM. Increase in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the United States, 1999–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2009 Sep;(22):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morasco BJ, Gritzner S, Lewis L, Oldham R, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment outcomes for chronic non-cancer pain in patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Pain. 2011 Mar;152(3):488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krebs EE, Ramsey DC, Miloshoff JM, Bair MJ. Primary Care Monitoring of Long-Term Opioid Therapy among Veterans with Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2011 May;12(5):740–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Starrels JL, Becker WC, Weiner MG, Li X, Heo M, Turner BJ. Low Use of Opioid Risk Reduction Strategies in Primary Care Even for High Risk Patients with Chronic Pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Sep;26(9):958–964. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Dobscha SK. Adherence to clinical guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic pain in patients with substance use disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Sep;26(9):965–971. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1734-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]