Abstract

Objective

To compare patient’s retrospectively reported baseline quality of life before intensive care hospitalization with population norms and proxy reports.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

13 intensive care units at 4 teaching hospitals in Baltimore, MD, USA.

Patients

140 acute lung injury survivors and their designated proxies.

Interventions

Around the time of hospital discharge, both patients and proxies were asked to retrospectively estimate patients' baseline quality of life before hospital admission using the EQ-5D quality of life instrument.

Measurements and Main Results

Mean patient-rated EQ-5D visual analog scale scores and utility scores were significantly lower than population norms, but were significantly higher than proxy ratings. However, the magnitude of difference in average utility scores between patients and either population norms or proxies were not clinically important. For the 5 individual EQ-5D domains, kappa statistics revealed slight to fair agreement between patients and proxies. Bland-Altman plots demonstrated that for both the visual analog scale and utility scores, proxies underestimated scores when patients reported high ratings and overestimated scores for low patient ratings.

Conclusion

Patients retrospectively reported worse baseline health status before acute lung injury than population norms and better status than proxy reports; however, the magnitude of these differences in health status may not be clinically important. Proxies had only slight to fair agreement with patients in all 5 EQ-5D domains, attenuating patients’ more extreme ratings towards moderate scores. Caution is required when interpreting proxy retrospective reports of baseline health status for survivors of acute lung injury.

Keywords: Critical care; Quality of life; Acute lung injury; Proxy; Respiratory distress syndrome, adult; Health status

Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) survivors experience worse quality of life (QOL) than age- and sex-matched population norms.(1–8) Compared to other ICU patients, acute lung injury (ALI) patients represent those most likely to have the poorest QOL because of high illness severity, extended ICU stay, and frequent new morbidity after hospitalization.(4;5;9;10)

Reliably benchmarking patient’s QOL during their recovery ideally involves comparisons with pre-hospitalization baseline measures. Baseline QOL is also important because it can aid in prognostication and decision making in the ICU.(2) However, most ICU admissions are emergent and unexpected. Hence, baseline QOL cannot be obtained directly from the patient at admission. Alternatively, baseline QOL can be obtained retrospectively from survivors or from proxies. However, QOL obtained from these alternative methods may be subject to bias.

In our own study of ALI survivors, we found only fair to moderate agreement between patient and proxy estimates of the patients’ baseline QOL measured by the SF-36.(11) This finding is consistent with another cohort of ALI survivors.(12) However, QOL ratings were comparable between patient and proxy in studies with non-ALI patients such as elective surgery(13), chronic disease(14) and general ICU patients.(15–18)

With these conflicting data on patient and proxy agreement, we sought to further evaluate patient versus proxy assessments of baseline QOL in ALI survivors using the EQ-5D survey. The EQ-5D is much shorter than the SF-36 with only 3 response options for each question; hence, it might produce better patient-proxy agreement. Our study has two specific objectives: (1) to compare baseline EQ-5D QOL measures of ALI survivors versus age- and sex-matched population norms, and (2) to evaluate the agreement of proxy versus patient estimates of baseline QOL.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

Data for this analysis was obtained from an ongoing prospective cohort study, (19) which consecutively enrolled ALI patients from 13 intensive care units at four teaching hospitals in Baltimore, USA. Eligible patients were ≥ 18 years old and mechanically ventilated with ALI as defined by the American-European Consensus Conference criteria.(20) Relevant exclusion criteria evaluated at the time of ALI diagnosis included preexistence of: 1) comorbid disease with a life expectancy of <6 months; 2) communication or language barrier; 3) cognitive impairment; and 4) no fixed address. The institutional review boards (IRB) of the Johns Hopkins University and all participating institutions approved of this study.

Patients were generally consented after discharge from ICU.(21) Thereafter, consented patients provided the name and contact information for their closest proxies. At the time of this study, only one version of the EQ-5D was available, which is now known as the EQ-5D-3L. This EQ-5D instrument was generally administered in person to patients and before hospital discharge, while proxies, who were generally not available in hospital after patient consent, were interviewed via phone. Both patients and proxies were instructed to estimate baseline QOL, defined as just before the onset of the illness that resulted in patients’ ALI hospitalization. Proxies were explicitly instructed to respond using the patient’s perspective.(22;23)

The EQ-5D QOL(24) instrument consists of two sections: the descriptive system and the visual analogue scale (VAS). The descriptive system assesses the following five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each domain is assessed using a single question with three possible response options: no problems, some problems, or extreme problems. The individual domains can be converted to a utility score, a continuous range from −0.59 to 1.00, with 1.00 indicating “full health” and 0 representing death.(25) A negative EQ-5D utility score represents a health state valued as worse than dead. The VAS records the respondent’s self-rated health state on a 0 to 100 scale where the endpoints are labeled ‘Best imaginable health state’ (100) and ‘Worst imaginable health state’ (0).

Statistical Analysis

For both the VAS and utility scores, the mean of paired differences between patient and proxy and between patient and age- and sex-matched population norms(26) were compared using t-tests. Additionally, the mean of paired differences in the utility scores was compared to the estimated EQ-5D minimal important difference (MID) of 0.074, (27) using a t-test.

For each EQ-5D domain, the mean difference between each patient-proxy pair was calculated. Agreement between patient and proxy responses was measured using the Cohen’s kappa statistic (unweighted and weighted).(28) The kappa statistic can range from −1 (complete disagreement), to 0 (no agreement), to +1 (perfect agreement).(29) For the weighted kappa, weights were assigned using a standard method for linear weighting proposed by Cicchetti and Allison.(30) Given that each EQ-5D domain consists of 3 response options, the weights used were 1 for perfect agreement, 0.5 for responses that differed by 1 response level and 0 for comparing the maximum difference of 2 response levels (i.e. “no problems” vs. “extreme problems”). Based on the kappa statistic, patient-proxy agreement was qualitatively described according to recommendations from Landis and Koch: poor (κ < 0), slight (κ 0 – 0.2), fair (κ 0.21-0.4), moderate (κ 0.41 – 0.60), substantial (κ 0.61-0.8), or almost perfect (κ ≥ 0.81).(29)

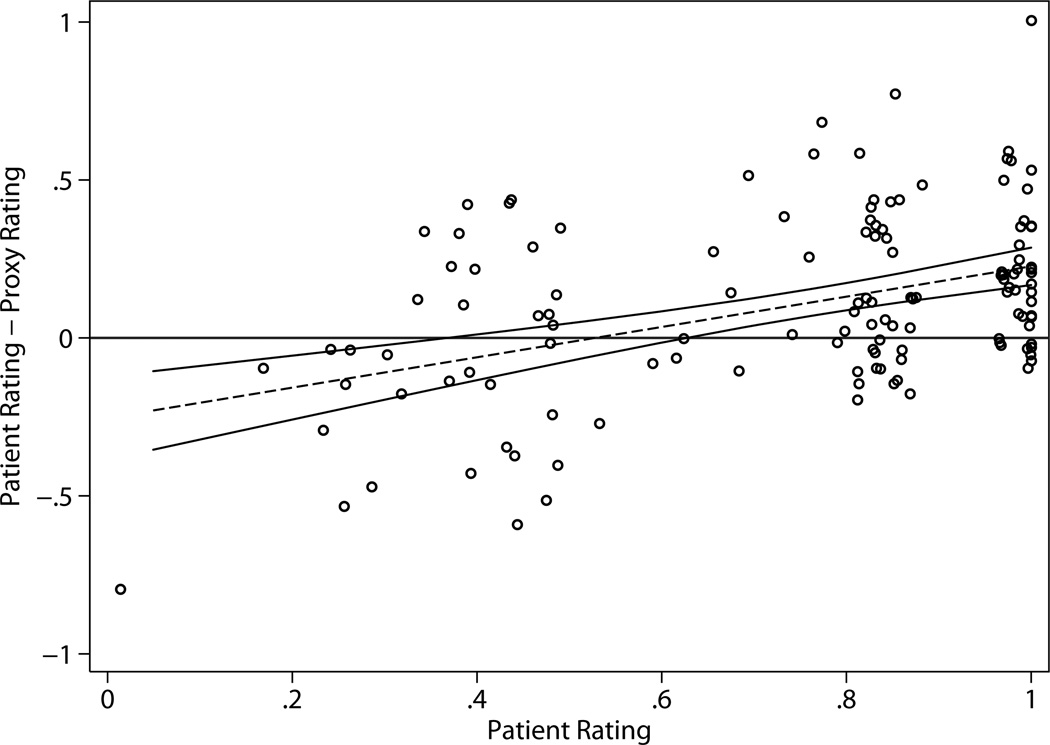

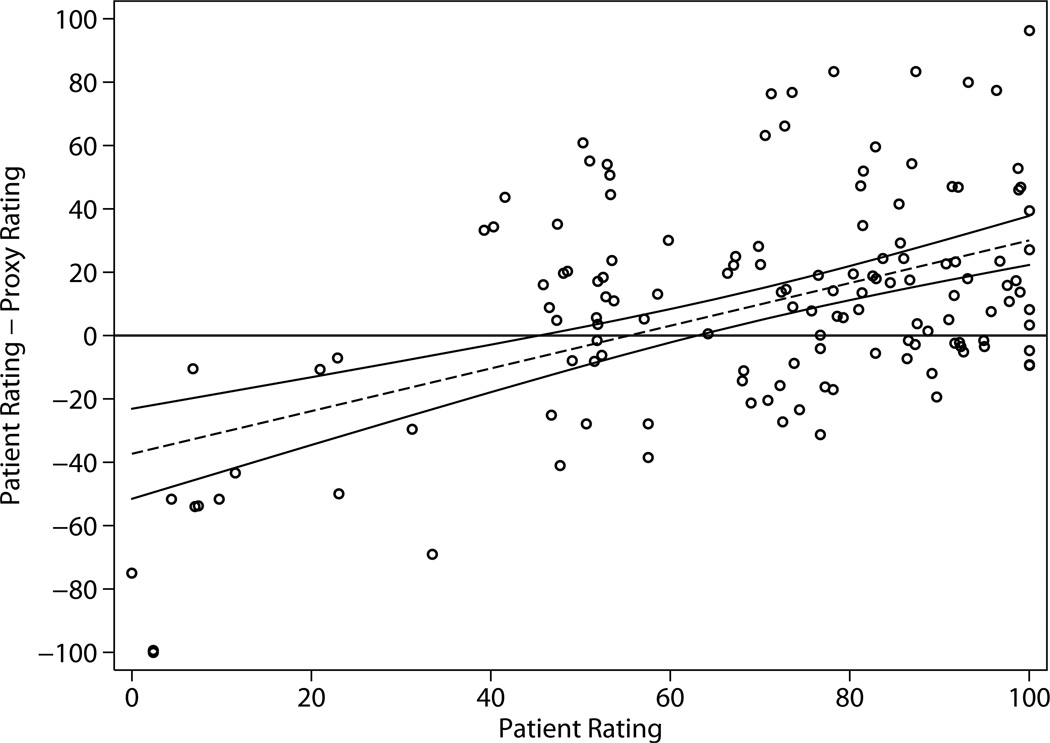

In addition, Bland-Altman plots were used to explore the relationship between differences in patient and proxy responses as a function of the patient response.(31) A traditional Bland-Altman plot would display the average of the patient and proxy responses along the horizontal axis. However, for this analysis, it was assumed that the patient response is measured without error, so that the patient response is most reflective of the true underlying quality of life and most appropriate for the x-axis. For the Bland-Altman plots, linear regression models were used to estimate the mean difference in patient and proxy responses as a function of the patient response.

For all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using STATA version 10.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 187 participants were potentially eligible for this patient-proxy QOL analysis. Of these, 40 were not eligible for the following reasons: patient cognitive impairment (n=24); no proxy available (n=9); death or hospice care prior to completion of surveys (n=7). Only 7 (5%) of 147 were excluded due to either the patient or proxy declining to complete the survey. Hence, the EQ-5D data were analyzed for 140 patient-proxy pairs. Patients were mechanically ventilated for an average (standard deviation) of 12.6 (11.3) days. Table 1 describes baseline characteristics of the patients included in this study.

Table 1.

Description of study participants

| Baseline characteristic | N=140a |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) years | 49 (40, 60) |

| Male, no. (%) | 75 (54) |

| Race, no. (%) | |

| White | 88 (63) |

| African-American | 50 (36) |

| Other | 2 (1) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 3) |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR) | 23 (17, 27) |

| ICU admission diagnosis, no. (%) | |

| Respiratory, including pneumonia | 80 (57) |

| Gastrointestinal | 18 (13) |

| Sepsis (non-pulmonary source) | 10 (7) |

| Infectious disease | 9 (6) |

| Trauma | 6 (4) |

| Cardiovascular | 4 (3) |

| Other | 13 (9) |

| ICU type, no. (%) | |

| Medical | 111 (79) |

| Surgical | 19 (14) |

| Trauma | 10 (7) |

Abbreviations: APACHE II – Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; IQR – Interquartile Range

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

When comparing patient reports versus matched population norms (Table 2), the mean paired difference in VAS score was 10.6 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): −14.9, −6.3) points lower in patients. The mean paired difference in utility scores was 0.108 (95% CI: −0.151, −0.065) points lower in patients than the population norms, but this difference was not significantly greater than the estimated EQ-5D minimal important difference of 0.074 (p=0.121).(27)

Table 2.

Patient versus population norms for baseline quality of life using EQ-5D

| EQ-5D section | Na | Mean Patient Score |

Mean Age- and Sex-Matched Population norm |

Mean paired difference [95% CI] (population - patient) |

P value for difference > 0b |

P value for difference ≥ MIDc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Analogue Score | 136 | 69.2 | 79.8 | 10.6 [14.9, 6.3] | <0.001 | N/A |

| Utility Score | 134 | 0.752 | 0.860 | 0.108 [0.151, 0.065] | <0.001 | 0.121 |

Abbreviations: CI – confidence intervals. MID - minimal important difference

Four patients were missing VAS scores and 6 had missing data for at least one domain, which prevents calculation of the utility score

P-value for testing if the mean paired difference is greater than zero

P-value for testing if the mean paired difference is greater than the minimum important difference 0.074 (27)

The distribution of responses among proxies within each patient response option is presented in Table 3. The mean-paired difference for the patient-proxy comparison (Table 4) demonstrated significantly better ratings by patients for both the VAS and the utility scores, with a mean paired difference of 9.3 (95% CI: 3.5, 15.1) and 0.108 (95% CI: 0.060, 0.155), respectively. However, the magnitude of the mean-paired difference in utility score was not larger than the EQ-5D minimal important difference of 0.074 (p=0.165).(27)

Table 3.

Distribution of responses among the EQ-5D domains in patients and proxies

| Patient Responses |

Proxy Responses |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Problem | Some Problem | Extreme Problem | ||

| Mobility, n | 140 | |||

| No Problem | 74% | 65% | 30% | 5% |

| Some Problem | 24% | 18% | 64% | 18% |

| Extreme Problem | 2% | 33% | 0% | 67% |

| Self-care, n | 140 | |||

| No Problem | 88% | 83% | 14% | 3% |

| Some Problem | 11% | 40% | 47% | 13% |

| Extreme Problem | 1% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| Usual Activities, n a | 139 | |||

| No Problem | 78% | 69% | 19% | 12% |

| Some Problem | 18% | 40% | 48% | 12% |

| Extreme Problem | 4% | 33% | 33% | 33% |

| Pain/Discomfort, n a | 136 | |||

| No Problem | 54% | 42% | 46% | 12% |

| Some Problem | 25% | 24% | 50% | 26% |

| Extreme Problem | 21% | 18% | 39% | 43% |

| Anxiety/Depression, n a | 139 | |||

| No Problem | 60% | 55% | 36% | 8% |

| Some Problem | 30% | 31% | 40% | 29% |

| Extreme Problem | 10% | 7% | 36% | 57% |

Usual activities and anxiety/depression were missing 1 patient/proxy pair and pain/discomfort had 4 missing pairs.

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Table 4.

Patient versus proxy comparison for baseline quality of life using EQ-5D

| Na | Mean Patient Score |

Mean Proxy Score |

Mean paired difference [95% CI] (patient – proxy) |

P value for difference > 0 b |

P value for difference ≥ MIDc |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Analogue Score | 136 | 69.2 | 59.9 | 9.3 [3.5, 15.1] | 0.002 | N/A |

| Utility Score | 134 | 0.752 | 0.644 | 0.108 [0.060, 0.155] | <0.001 | 0.165 |

Abbreviations: CI – confidence intervals. MID - minimal important difference

Four patients were missing VAS scores and 6 had missing data for at least one domain, which prevents calculation of the utility score

P-value for testing if the mean paired difference is greater than zero

P-value for testing if the mean paired difference is greater than the minimum important difference 0.074 (27)

The weighted kappa statistics revealed that patient-proxy agreement was “slight” to “fair” for all 5 EQ-5D domains (kappa range: 0.20 – 0.34) with relatively similar results from the unweighted kappa (range: 0.16 – 0.32; Table 5). Analysis of Bland-Altman plots for both the VAS and utility scores reveals that for both EQ-5D utility and VAS scores, proxy evaluations tended to attenuate the patient ratings. For example, when patients reported VAS scores greater than 60, most proxies provided lower scores, which are represented by the open circle symbols appearing above the horizontal line on the plot that represents no difference between patient and proxies. Points below this horizontal line indicate that proxies provided higher scores than patients which occurred universally when patients reported low VAS scores (e.g. scores less than 40).

Table 5.

Agreement between patient and proxy baseline quality of life assessment using EQ-5D

| EQ-5D domain | N | Kappa [95% CI] | Weighteda Kappa [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | 140 | 0.32 [0.19, 0 .45] | 0.34 [0.21, 0.46] |

| Self-Care | 140 | 0.27 [0.13, 0.40] | 0.29 [0.15, 0.42] |

| Usual Activities | 139 | 0.22 [0.09, 0 .34] | 0.20 [0.08, 0.33] |

| Pain/Discomfort | 136 | 0.16 [0.05, 0.27] | 0.22 [0.10, 0.35] |

| Anxiety/Discomfort | 139 | 0.20 [0.08, 0.32] | 0.29 [0.16, 0.41] |

Abbreviations: CI – confidence intervals.

A weight of 1 is assigned for perfect agreement, 0.5 for responses differing by one level, and 0 for a difference of two levels that is the largest possible disagreement. (30)

Discussion

This prospective cohort study examined patient-proxy agreement in retrospectively reported baseline EQ-5D QOL of 140 ALI patients. Patients reported worse baseline QOL than population norms. The 140 patient-proxy pairs in this cohort had only slight to fair agreement in all 5 domains of EQ-5D with proxies responses biased toward the EQ-5D response option of “some problem” when the patient chose either “no” or “extreme” problems. On average, proxies (versus patients) reported lower baseline VAS and utility scores. However, the magnitude of this difference in utility scores was not clinically important.(27)

The importance of establishing accurate baseline QOL status of ICU patients motivates this analysis. In this study, patients retrospectively reported worse baseline QOL than the normal population, consistent with prior studies.(2;5;6;8;11;32) Consequently, using population norms as a substitute for a patient’s baseline QOL status may exaggerate the QOL impairments frequently observed during recovery after ICU.(2;4–8) Proxies may be potential source of patient baseline status. However, prior studies have reported varying degrees of agreement on QOL between proxies and patients.(11–18)

Despite the EQ-5D being markedly shorter and having fewer response options than the SF-36, there was only slight to fair agreement in all five domains between patients and proxies in this study. However in a population of trauma patients, agreement among the EQ-5D domains between patient and proxy were moderate to substantial.(33) Moreover, in a prior study evaluating agreement between patient- and proxy-reported baseline EQ-5D for general ICU patients, there was moderate to good agreement in mobility, self-care, usual activities, and pain/discomfort domains, and fair agreement for anxiety/depression domain, and very similar VAS scores.(15) These results were replicated by the same group with a larger cohort.(34) In our study, patient-proxy pairs had fair agreement in all the domains, with mobility having the best agreement and pain having the worst agreement. These results may differ from ours due to differences in patient populations, including higher severity of illness in our cohort. Additionally, proxies in our study were interviewed via phone after the patients’ ICU discharge, while in the other ICU studies, proxy interviews were conducted via a self-administered survey immediately after ICU admission. Consequently, it may be that our study found proxies to be unreliable sources of patient’s baseline EQ-5D because our study design and cohort of patient were substantially different from the prior research that did not demonstrate problems with patient and proxy agreement in using the EQ-5D instrument.

There are several potential limitations of this study. First, there is no estimated EQ-5D MID for ICU survivors. We do not know if the MID cited in this study (27) is applicable for ICU patients, but provided it as a reference point for consideration. Second, data was not available for 25% of survivors. However, the majority of these missed assessments were unavoidable due to death, discharge to hospice, or cognitive impairment, which is consistent with other studies.(34;35) Only 5% of eligible patients or proxies declined to provide EQ-5D responses, comparable to similar studies.(15) Third, this study did not collect data on the nature of the relationship between patient and proxy, but interviewers made earnest attempts to reach the closest proxy available, as designated by the patient for this purpose. Furthermore, other literature has shown that patient-proxy relationship has no effects on agreement.(17;18;34) Lastly, the difference in mode of administration may have influenced our results since patient interviews were conducted in-person while proxies’ were conducted by phone.(36) However, by allowing for more than one mode of administration, the study offered flexibility to patients and proxies, which potentially minimized non-response bias, given that proxies were infrequently available for in-person assessments.

Conclusions

Our comparison of patient-proxy agreement in retrospective reporting of ALI patient’s baseline QOL prior to hospital admission revealed slight to fair agreement for all EQ-5D domains with evidence of proxy reports biased towards less extreme responses. These findings indicate that caution should be exercised if retrospectively obtaining baseline QOL data from proxies for survivors of acute lung injury.

Figure 1. Bland-Altman Plots for EQ-5D Utility and VAS scores.

1a: EQ-5D utility score

1b: EQ-5D visual analogue scale score

These figures display the relationship between patient-rated EQ-5D score and the difference between patient- and proxy-rated scores. The dashed line is the fitted linear regression of the relationship, while the upper and lower lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Acknowledgment

We thank all patients and proxies who participated in the study and the dedicated research staff who assisted with the study: Mr. Doug Ammerman, Ms. Rachel Bell, Ms. Kim Boucher, Dr. Abdulla Damluji, Ms. Carinda Field, Ms. Lisa Fiol-Powers, Ms. Mirinda Gillespie, Ms. Kristin Giuliani, Ms. Tajrina Hai, Ms. Thelma Harrington, Ms. Toni Harrison, Ms. Lauren Heinrich-Smith, Dr. Kashif Janjua, Dr. Praveen Kondreddi, Ms. Cassie Kryzak, Ms. Frances Magliacane, Ms. Stacey Murray, Ms. Hannah Reddick, Ms. Omoleye Roberts, Ms. Amaris Rosario, Dr. Shabana Shahid, Ms. Winnie Shu, Ms. Michelle Silas, Dr. Siddharth Sura, Mr. Jerold Weier, Ms. Robyn Weisman, Dr. Addisu Workneh, and Ms. Rebecca Zimmerman.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Acute Lung Injury SCCOR Grant # P050 HL 73994). Dr. Needham was supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funding bodies had no role in the study design, manuscript writing or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Chaboyer W, Elliott D. Health-related quality of life of ICU survivors: review of the literature. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2000 Apr;16(2):88–97. doi: 10.1054/iccn.1999.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofhuis JG, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, Schrijvers GJ, Rommes JH, Bakker J. The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: a long-term follow-up study. Chest. 2008 Feb;133(2):377–385. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaarlola A, Pettila V, Kekki P. Quality of life six years after intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Aug;29(8):1294–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Sedrakyan A, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, Herridge MS, Needham DM. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: A systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2005 May;31(5):611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Dennison CR, Mendez-Tellez PA, Herridge MS, Guallar E, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006 Aug;32(8):1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner EH, Warrillow S, Denehy L. Health-related quality of life in Australian survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2011 Aug;39(8):1896–1905. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b8421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N.Engl.J.Med. 2011 Apr 7;364(14):1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, Maclennan G, Vale L. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2010 Jan 20;14(1):R6. doi: 10.1186/cc8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davydow DS, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review. Psychosom.Med. 2008 May;70(4):512–519. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011 Feb;39(2):371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gifford JM, Husain N, Dinglas VD, Colantuoni E, Needham DM. Baseline quality of life before intensive care: A comparison of patient versus proxy responses. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:855–860. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cd10c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scales DC, Tansey CM, Matte A, Herridge MS. Difference in reported pre-morbid health-related quality of life between ARDS survivors and their substitute decision makers. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1826–1831. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott D, Lazarus R, Leeder SR. Proxy respondents reliably assessed the quality of life of elective cardiac surgery patients. J.Clin.Epidemiol. 2006 Feb;59(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sneeuw KC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease. J.Clin.Epidemiol. 2002 Nov;55(11):1130–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badia X, Diaz-Prieto A, Rue M, Patrick DL. Measuring health and health state preferences among critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1996 Dec;22(12):1379–1384. doi: 10.1007/BF01709554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofhuis J, Hautvast JL, Schrijvers AJ, Bakker J. Quality of life on admission to the intensive care: can we query the relatives? Intensive Care Med. 2003 Jun;29(6):974–979. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1763-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capuzzo M, Grasselli M, Carrer S, Gritti G, Alvisi R. Quality of life before intensive care admission: agreement between patient and relative assessment. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1288–1295. doi: 10.1007/s001340051341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers J, Ridley S, Chrispin P, Scotton H, Lloyd D. Reliability of the next of kins' estimates of critically ill patients' quality of life. Anaesthesia. 1997 Dec;52(12):1137–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.240-az0374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Needham DM, Dennison CR, Dowdy DW, Mendez-Tellez PA, Ciesla N, Desai SV, Sevransky J, Shanholtz C, Scharfstein D, Herridge MS, et al. Study protocol: The Improving Care of Acute Lung Injury Patients (ICAP) study. Crit Care. 2006 Feb;10(1):R9. doi: 10.1186/cc3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am.J Respir.Crit Care Med. 1994 Mar;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan E, Shahid S, Kondreddi VP, Bienvenu OJ, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Informed consent in the critically ill: a two-step approach incorporating delirium screening. Crit Care Med. 2008 Jan;36(1):94–99. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295308.29870.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McPhail S, Beller E, Haines T. Two perspectives of proxy reporting of health-related quality of life using the Euroqol-5D, an investigation of agreement. Med Care. 2008 Nov;46(11):1140–1148. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d69a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickard AS, Knight SJ. Proxy evaluation of health-related quality of life: a conceptual framework for understanding multiple proxy perspectives. Med Care. 2005 May;43(5):493–499. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160419.27642.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990 Dec;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. A social tariff for EuroQol: results from a UK general population survey. University of York: Centre for Health Economics; 1995. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanmer J, Lawrence WF, Anderson JP, Kaplan RM, Fryback DG. Report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for 7 health-related quality-of-life scores. Med.Decis.Making. 2006 Jul;26(4):391–400. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual.Life Res. 2005 Aug;14(6):1523–1532. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7713-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol.Bull. 1968 Oct;70(4):213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977 Mar;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cicchetti DV, Allison T. A new procedure for assessing reliability of scoring EEG sleep recordings. American Journal of EEG Technology. 1971;(11):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehler M, Geise A, Hadzionerovic D, Aljukic E, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, Strauss R. Health-related quality of life of patients with multiple organ dysfunction: individual changes and comparison with normative population. Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr;31(4):1094–1101. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059642.97686.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabbe BJ, Lyons RA, Sutherland AM, Hart MJ, Cameron PA. Level of agreement between patient and proxy responses to the EQ-5D health questionnaire 12 months after injury. J.Trauma Acute.Care Surg. 2012 Apr;72(4):1102–1105. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182464503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz-Prieto A, Gorriz MT, Badia X, Torrado H, Farrero E, Amador J, Abos R. Proxy-perceived prior health status and hospital outcome among the critically ill: is there any relationship? Intensive Care Med. 1998 Jul;24(7):691–698. doi: 10.1007/s001340050646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001 Dec 5;286(21):2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanmer J, Hays RD, Fryback DG. Mode of administration is important in US national estimates of health-related quality of life. Med.Care. 2007 Dec;45(12):1171–1179. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181354828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]