Abstract

AIM: To investigate endoscopic findings in patients with Schatzki rings (SRs) with a focus on evidence for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

METHODS: We consecutively approached all adult patients scheduled for elective outpatient upper endoscopy for a variety of indications at the German Diagnostic Clinic, Wiesbaden, Germany between July 2007 and July 2010. All patients with endoscopically diagnosed SRs, defined as thin, symmetrical, mucosal structures located at the esophagogastric junction, were prospectively registered. Additional endoscopic findings, clinical information and histopathological findings with a focus on esophageal eosinophilia (≥ 20 eosinophils/high power field) were recorded. The criteria for active EoE were defined as: (1) eosinophilic tissue infiltration ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf; (2) symptoms of esophageal dysfunction; and (3) exclusion of other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease was excluded by proton pump inhibitor treatment prior to endoscopy. The presence of ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf in esophageal biopsies in patients that did not fulfil the criteria of EoE was defined as esophageal hypereosinophilia.

RESULTS: A SR was diagnosed in 171 (3.3%; 128 males, 43 females, mean age 66 ± 12.9 years) of the 5163 patients that underwent upper gastrointestinal-endoscopy. Twenty of the 116 patients (17%) from whom esophageal biopsies were obtained showed histological hypereosinophilia (≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf). Nine of these patients (8 males, 1 female, mean age 49 ± 10 years) did not fulfill all diagnostic criteria of EoE, whereas in 11 (9%) patients with ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf, a definite diagnosis of EoE was made. Three of the 11 patients (27%) with definite EoE had no suspicious endoscopic features of EoE. In contrast, in the 25 patients in whom EoE was suspected by endoscopic features, EoE was only confirmed in 7 (28%) patients. Patients with EoE were younger (mean age 41.5 ± 6.5 vs 50.5 ± 11.5 years, P = 0.012), were more likely to have a history of allergies (73% vs 29%, P = 0.007) and complained more often of dysphagia (91% vs 34%, P = 0.004) and food impaction (36% vs 6%, P = 0.007) than patients without EoE. Endoscopically, additional webs were found significantly more often in patients with EoE than in patients without EoE (36% vs 11%, P = 0.04). Furthermore, the SR had a tendency to be narrower in patients with EoE than in those without EoE (36% vs 18%, P = 0.22). The percentage of males (73% vs 72%, P = 1.0) and frequency of heartburn (27% vs 27%, P = 1.0) were not significantly different in both groups. The 9 patients with esophageal hypereosinophilia that did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria of EoE were younger (mean age 49 ± 10 years vs 58 ± 6 years, P = 0.0008) and were more likely to have a history of allergies (78% vs 24%, P = 0.003) than patients with < 20 eosinophils/hpf. Predictors of EoE were younger age, presence of dysphagia or food impaction and a history of allergies.

CONCLUSION: A significant proportion of patients with SRs also have EoE, which may not always be suspected according to other endoscopic features.

Keywords: Schatzki ring, Dysphagia, Esophageal eosinophilia, Eosinophilic esophagitis, Food impaction

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of a lower esophageal Schatzki ring (SR) ranges from 4%-15%, depending on the diagnostic method and population investigated. In the majority of cases, it does not cause any symptoms, however, it is also one of the most common causes of intermittent dysphagia and food impaction[1-3]. The etiology and pathogenesis still remain unclear. Gastroesophageal reflux disease has been suggested as an etiological factor[4]. However, prospective studies have documented an association with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in less than two-thirds of patients[5,6]. Therefore, additional pathogenetic factors should be considered.

More recently, an association of SRs with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has been reported[7,8], although the causal relationship between the two entities is under discussion[9-11].

The aim of this study was to obtain additional endoscopic findings and assess the prevalence of EoE in patients with SRs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

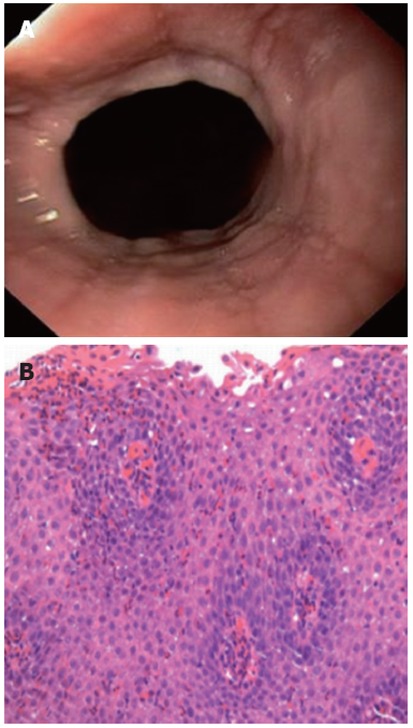

We consecutively approached all adult patients scheduled for elective outpatient upper endoscopy for a variety of indications at the German Diagnostic Clinic, Wiesbaden between July 2007 and July 2010. We recruited all patients in which we could endoscopically identify a lower esophageal SR. A SR was defined as a thin, symmetric, mucosal structure located at the esophagogastric junction (Figure 1A)[12]. Data including sex, medical history, medications, allergies, additional endoscopic findings and esophageal biopsy results were recorded.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic image and histological image of eosinophilic esophagitis. A: Endoscopic image showing a lower esophageal Schatzki ring and linear furrowing of the esophageal mucosa, an endoscopic feature associated with eosinophilic esophagitis; B: Histological image of an esophageal biopsy, showing eosinophilic esophagitis with numerous intraepithelial eosinophils (> 50 eosinophils/high power field, hematoxylin and eosin, × 400).

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained (approved by the Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Forschung an der Deutschen Klinik für Diagnostik; GFF Approval No. IRB-2012-I), medical records were reviewed to assess symptoms, medical history, medications and endoscopic findings of all patients with SRs in whom esophageal biopsies were obtained to determine the prevalence of EoE. Patients with concomitant eosinophilic infiltration in the stomach or duodenum and patients with known Barrett’s esophagus were excluded.

Endoscopy

Endoscopic findings for patients consenting to participate in the study were prospectively recorded in an electronic database (Clinic Win Data, E+L GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). All endoscopies were performed by senior gastroenterologists with a GIF 160 or GIF 180 Olympus upper endoscope (Olympus Corp., Hamburg, Germany) with an outer diameter of 9.5 mm. The internal diameter of the SR was estimated during endoscopy. A narrow ring was defined as being difficult to pass through with the endoscope and a wide ring was easy to pass through with the endoscope. A sliding hiatal hernia was diagnosed when gastric mucosa folds extended for more than 1.5 cm above the diaphragm[13].

Erosive esophagitis was classified according to the criteria of the Los Angeles classification system[14,15]. An esophageal web was defined as an eccentric, mucosal narrowing proximal to the esophagogastric junction having a maximum thickness of 1.5 mm[16]. The diagnosis of a diverticulum was based on the presence of a pouch in the esophagus (Zenker’s diverticulum: pouch in the pharyngoesophageal area; midesophageal diverticulum: pouch in the mid esophagus; epiphrenic diverticulum: pouch just proximal to the diaphragm)[16]. EoE was assumed with the presence of linear furrows, whitish exudates, trachealization or a small calibre esophagus[17].

Following the standard procedure in our department, all patients in whom no otherwise obvious cause of their symptoms could be detected (e.g., reflux esophagitis, malignant or peptic strictures) and who had no recent exposure to anticoagulants had esophageal biopsies. This was done using a standard biopsy protocol, which included 2 duodenal biopsies, 2 gastric biopsies and a total of 4 esophageal biopsies (2 distal within 5-8 cm proximal to the esophagogastric junction, and 2 mid > 10 cm proximal the esophagogastric junction).

Histopathological assessment

Biopsy specimens were submitted for routine processing and pathology evaluation with a request to evaluate for EoE. All histopathological analyses were performed by senior pathologists. The peak count of intraepithelial eosinophils/high power field (× 400 magnifications on the Optiphot-2 microscope, ocular × 10 with Plan × 40 objective; Nikon, Japan) was determined in the area of highest density of eosinophils using the most densely populated hpf. Histological suspicion of EoE was the presence of 20 or more eosinophils/hpf[10,17]. In biopsy specimens with ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf, a thorough histopathological review was performed by a second senior pathologist according to further histological features associated with EoE, including a particular affiliation of eosinophils to aggregate in the surface layers of the epithelium, the presence of microabscesses (defined by ≥ 4 eosinophils/cluster), findings of epithelial hyperplasia (basal-zone expansion of 30% and papillary height elongation of > 70%) and lamina propria fibrosis[18,19](Figure 1B).

Definition of EoE

Criteria of active EoE were defined as: (1) eosinophilic tissue infiltration ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf; this cut-off was chosen as the study was designed prior to the publication of the AGA guidelines[17]; (2) symptoms of esophageal dysfunction (dysphagia, food impaction and PPI-resistant heartburn); and (3) exclusion of other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was excluded by proton pump inhibitor treatment prior to endoscopy.

The presence of ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf in esophageal biopsies in patients that did not fulfil the criteria of EoE was defined as esophageal hypereosinophilia.

Statistical analysis

Numeric variables are described as the mean ± SD and the number of observations (n). Categorical variables are described using frequencies (n) and percentages (%). In order to assess whether group differences were compatible with pure chance, we performed exploratory tests. Therefore, all reported P-values are descriptive. Association of age with categorical variables was assessed by the two-sample Wilcoxon test. Association of categorical variables was tested using Fisher’s exact test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 5163 patients underwent upper gastrointestinal-endoscopy in our department. A SR was diagnosed in 171 (3.3%) patients (128 males, 43 females, mean age 66 ± 12.9 years). Reflux esophagitis was present in 45 patients (who were then excluded from the analysis) and an additional 10 patients were excluded because of the presence of peptic stenosis (n = 1), Barrett´s esophagus (n = 6), and esophageal malignancy (n = 1). Two patients were on anticoagulation therapy and therefore a biopsy specimen was not taken.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the 116 patients enrolled are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all enrolled patients with Schatzki rings n (%)

| Variables | Schatzki ring (n = 116) |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 55.2 ± 4.9 |

| Gender (M/F) | 84/32 |

| History of allergy | 34 (29) |

| Dysphagia | 47 (41) |

| History of food impaction | 9 (8) |

| Heartburn | 31 (27) |

| No symptoms of esophageal dysfunction | 31 (27) |

M/F: Male/female.

The endoscopically estimated diameter of the lower esophageal ring was wide in 93 (80%) and narrow in 13 (11%) patients. The most frequent additional endoscopic finding was a sliding hiatal hernia in 95 (82%) patients. Sixteen (14%) of 116 patients showed esophageal webs and 3 (3%) patients had esophageal diverticula. One of the 3 patients with esophageal diverticula showed a Zenker’s diverticulum and, in 2 patients, midesophageal diverticula were diagnosed. EoE was assumed in 25 (21%) patients because of the presence of specific endoscopic features.

In 20 (17%; 16 males, 4 females, mean age 39 ± 6 years) of the 116 patients, hypereosinophilia (≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf) could be shown in the esophageal biopsies. The results of the histopathological analysis of these specimens are shown in Table 2. Biopsy specimens of the stomach and duodenum of these patients showed no evidence of eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Crohn’s disease or infection.

Table 2.

Histopathological features

| Patient ID | Age (yr) | Gender | Met the clinical criteria of EoE | Eosinophils/hpf | Further histological findings suspicious of EoE |

| 1 | 35 | M | Yes | 25 | H |

| 2 | 57 | M | Yes | 25 | S |

| 3 | 37 | M | Yes | 40 | H |

| 4 | 34 | M | Yes | 60 | M1, S, H |

| 5 | 31 | F | Yes | 20 | None |

| 6 | 43 | M | Yes | 50 | H |

| 7 | 44 | M | Yes | 45 | S, H |

| 8 | 43 | F | Yes | 45 | S, H, F |

| 9 | 48 | M | Yes | 55 | S, H, F |

| 10 | 23 | F | Yes | 35 | H |

| 11 | 35 | M | Yes | 60 | H |

| 12 | 60 | M | No | 20 | S, H |

| 13 | 44 | M | No | 20 | H |

| 14 | 46 | M | No | 25 | S, H, F |

| 15 | 47 | M | No | 60 | H |

| 16 | 39 | M | No | 45 | H |

| 17 | 29 | M | No | 45 | H |

| 18 | 35 | M | No | 60 | S, H |

| 19 | 39 | M | No | 25 | H |

| 20 | 39 | F | No | 30 | H |

Histopathological features of the 20 patients with a SR and hypereosinophilia (≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf) in the biopsy specimen of the esophagus. M: Male; F: Female; EoE: Eosinophilic esophagitis; F: Fibrosis of lamina propria; H: Epithelial hyperplasia; M1: Microabscess; S: Superficial layering of eosinophils; hpf: High power field.

Eleven of these 20 patients met the diagnostic criteria of EoE. Table 3 shows the baseline characteristics of the 11 patients with SRs and EoE. From the 25 patients in whom EoE was assumed because of the endoscopic features, EoE was confirmed in 7 (28%) patients. Three of the 11 patients (27%) with defined EoE had no suspicious endoscopic features of EoE.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics

| Patient ID | Age (yr) | Gender | Dysphagia | History of food impaction | History of allergy | Endoscopic findings suspicious of EoE |

| 1 | 35 | M | + | - | + | Furrows |

| 2 | 57 | M | + | - | + | None |

| 3 | 37 | M | + | + | - | Trachealization |

| 4 | 34 | M | - | + | + | Furrows, trachealization |

| 5 | 31 | F | + | + | + | Furrows |

| 6 | 43 | M | + | - | - | Whitish exudates |

| 7 | 44 | M | + | - | + | None |

| 8 | 43 | F | + | - | + | None |

| 9 | 48 | M | + | - | + | Furrows |

| 10 | 23 | F | + | - | + | Furrows |

| 11 | 35 | M | + | + | - | Furrows |

Baseline characteristics of the 11 patients with a Schatzki ring and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). M: Male; F: Female.

When compared with the remainder of the 116 patients, the 11 patients with documented EoE were of younger age, more often showed an allergic predisposition, and complained to a larger degree of dysphagia and food impaction (Table 4). Whereas no gender difference (27% vs 28% females, P = 1.0) was demonstrated between both groups, EoE was diagnosed in 50% of the patients < 45 years of age vs 3% in patients 45 years or older (relative risk 10).

Table 4.

Demographics, clinical and endoscopic findings n (%)

| Variable | SR with EoE (n = 11) | SR without EoE (n = 105) | P value |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 41.5 ± 6.5 | 50.5 ± 11.5 | 0.012 |

| Gender (M/F) | 8/3 | 76/29 | 1.0 |

| History of allergy | 8 (72.7) | 24 (29) | 0.007 |

| Dysphagia | 10 (90.9) | 36 (34.3) | 0.004 |

| History of food impaction | 4 (36.4) | 6 (5.7) | 0.007 |

| Heartburn | 3 (27.3) | 28 (26.7) | 1.0 |

| Ring narrow | 4 (36.4) | 19 (18.1) | 0.22 |

| Webs | 4 (36.4) | 12 (11.4) | 0.044 |

Demographics and clinical and endoscopic findings for patients with a Schatzki ring (SR) with and without eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). M: Male; F: Female.

Endoscopically, additional webs were found significantly more often in patients with EoE than in patients without EoE (36% vs 11%, P = 0.04). Furthermore patients with EoE had a tendency to have narrower SR than patients without EoE (36% vs 18%, P = 0.22). Nine patients (8 males, 1 female, mean age 49 ± 10 years) showed ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf in the histological examination, but did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria of EoE because gastroesophageal reflux disease could not be excluded prior to the esophageal biopsy sampling (6 patients) or the patients had no symptoms of esophageal dysfunction (3 patients had abdominal pain). Four (44%) of the 9 patients with esophageal hypereosinophilia complained of dysphagia and one of the 4 also had heartburn. One (11%) of the 9 patients had a history of food impaction and another (11%) had heartburn. The endoscopically estimated diameter of the lower esophageal ring was wide in 5 (56%) and narrow in 4 (44%) patients and 3 (33%) patients exhibited additional esophageal webs. EoE was assumed in 4 (44%) of those patients because of the endoscopic features.

Patients with esophageal hypereosinophilia were younger (mean age 49 ± 10 years vs 58 ± 6 years, P = 0.0008), were more likely to have a history of allergies (78% vs 24%, P = 0.003) and were more frequently found to have additional webs (33% vs 9%, P = 0.009) and more narrow SRs (44% vs 16%, P = 0.05) than patients with < 20 eosinophils/hpf. Furthermore, patients with esophageal hypereosinophilia had a tendency to complain less often of heartburn (11% vs 27%, P = 0.23). The number of males (89% vs 71%, P = 0.4), frequency of dysphagia (44% vs 33%, P = 0.5) and rate of food impaction (11% vs 5%, P = 0.4) were not significantly different in both groups.

Three of the 6 patients in whom GERD could not be excluded prior to biopsy sampling had relief of their symptoms after proton pump inhibitor treatment in standard doses for 4 wk following the endoscopy.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the prevalence of a lower esophageal SR was 3.3%, which is in the lower range of that reported in the literature[20]. SRs are seen in up to 14% of routine barium radiographs[2], however, similar to the presented data, symptomatic rings are less common and endoscopic examinations seem to be less accurate in diagnosing a ring[21,22]. This might be because endoscopic visualization of mucosal rings depends on proper distension of the esophagogastric region beyond the caliber of the ring, which is often not accomplished. This is especially true for the detection of wider rings[23].

SRs are frequently associated with erosive reflux esophagitis. Histologically, this might be reflected by increased tissue eosinophilia[24]. Therefore, those patients were excluded from further analysis. In 17.1% of the patients in whom esophageal biopsies were obtained, an esophageal hypereosinophilia with ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf was demonstrated. However, there also was significant overlap with EoE in more than half of those patients.

As was demonstrated in a previous study with a different cohort of patients, a SR is frequently associated with other esophageal disorders[25]. In the current investigation, erosive esophagitis was found in a quarter of the patients. Because of the frequent association, gastroesophageal reflux has been discussed by some authors as the main etiological factor for the development of a SR ring[4,25], while others have pointed out that GERD is only present in less than two-thirds of these patients and, therefore, might not be the only cause for the development of the ring[5,6]. However, inflammation, as a main pathogenic factor in the development of a SR, might be supported by the fact that, in the present study, esophageal hypereosinophilia with ≥ 20 eosinophils/hpf was a common finding in patients in whom esophageal biopsies were obtained, but only half of them met the diagnostic criteria for EoE according to the AGA guidelines[17].

In 6 of the 9 patients with esophageal hypereosinophilia, gastroesophageal reflux disease could not be excluded prior to the esophageal biopsy sampling and 3 patients complained of abdominal pain instead of symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. Because of this, they could not be diagnosed with EoE. Although some of these patients might have GERD, it is possible that some of these patients had early EoE. Particularly with regard to the fact that in 3 patients with an esophageal hypereosinophilia there was a surface layering of eosinophils, and in one a lamina propria fibrosis could be demonstrated, the findings were more typical of EoE than GERD[19]. Therefore, it could be assumed that the prevalence of EoE might actually be higher than 9% in the presenting group of patients with SRs. The association between SRs and EoE in children was first described by Nurko et al[7]. In a further prospective study that evaluated the etiology of esophageal bolus obstruction in adults, SRs were diagnosed in 9 of 37 patients, five (55.5%) of whom also exhibited EoE[9]. In contrast, such an association was not found in the investigation of Sgouros et al[9]. These discrepancies were explained by differences in life style and the age distribution of the populations under investigation[10]. Especially the latter argument could be supported by the results of Mackenzie et al[8]. Although it remains under debate whether the association between SRs and EoE is merely a coincidental finding of two common diseases or whether they share a common pathophysiology, in our opinion these data support the latter.

In the last decade, EoE has been increasingly recognized as a cause of dysphagia and food impaction. It is a chronic, immune/allergen mediated clinic-pathological disease of the esophagus characterized by dense eosinophilic inflammation[8]. The prevalence of EoE in an asymptomatic European population has been described as 0.4% and as 6.5% in a US population undergoing upper endoscopy for a variety of indications[26,27].

However, similar to the SR, the etiology of EoE is not completely understood and the connection between GERD and SRs, as well as the connection between GERD and EoE is still under debate[22,28]. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of this association because biopsies should be taken from the esophagus in patients with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction despite the presence of a SR. This may be obvious in cases that present with endoscopic features suspicious of EoE, such as linear furrows, trachealization, white plaques or a narrow caliber esophagus[18,29], but EoE may be present even in the absence of such features. Similar to other studies[30,31], the current investigation demonstrated that one-third of the patients do not present endoscopic features suspicious of EoE. Thus, the presence of EoE would have been missed in those patients if no biopsies had been obtained. We therefore suggest that routine biopsies should be taken from the esophagus in all symptomatic patients even in the presence of a SR, because EoE might be additionally present, even in the absence of other suggestive endoscopic features.

On the other hand, among the 25 patients that had endoscopic features suggestive of EoE, the diagnosis was confirmed by means of biopsy in only 28%. Therefore, endoscopic findings might not be reliable for supporting a diagnosis of EoE.

In the present study, the patients with SRs and EoE presented with symptoms of dysphagia, food impactions, and heartburn, all of which have been described as leading symptoms in both clinical entities[3,18,32]. Similar to previous observations of EoE, patients with SRs and EoE were younger and had a history of allergies more often than patients with SRs alone[18,29,30]. However, EoE was diagnosed in patients with SRs older than 50 years, in whom EoE was of unclear significance. It could be speculated that these patients had a late onset of the disease or that it represents a late diagnosis of a long-standing disease. The latter explanation might be more reasonable, due to the fact that EoE in adults is chronic and often indolent, especially when patients adapt their chewing habits over time[33].

In contrast to other studies of EoE[29,34], there was no gender preference in cases with SR and EoE, in comparison to those with SRs alone. This observation, however, might be due to a male preponderance for patients with SRs in the current investigation.

Endoscopically, patients with EoE had a tendency to have narrower rings than patients without EoE. Additional webs could be found significantly more often in patients with EoE than in patients without EoE. Although, 5%-15% of patients presenting with dysphagia are found to have esophageal webs[16], the etiology is often unknown. At least one study also showed a possible association with EoE[35], which was not confirmed by others[28,36]. However, in our opinion, narrow SRs and esophageal webs should raise the suspicion of EoE.

This study has its limitation in that 24 h esophageal pH monitoring was not available; therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the patients with esophageal hypereosinophilia might have had GERD instead of EoE. We attempted to overcome this limitation by administering PPI before the endoscopy.

In summary, the current data strongly suggest that the association of SRs and EoE in adults is not a chance finding but is a rather frequent coincidence that should be considered whenever one is confronted with a patient exhibiting a SR. Endoscopic findings might not be reliable for supporting a diagnosis of EoE. Therefore, it appears advisable to obtain esophageal biopsies, not only in the presence of typical endoscopic features of EoE, but also whenever a SR is detected in symptomatic patients, especially when a ring is narrow or patients are younger and have a history of allergies.

COMMENTS

Background

The Schatzki ring (SR) is the most common cause of episodic dysphagia to solid food, but its etiology and pathogenesis remain unknown. The most common theory as to its origin suggests inflammation, with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as the main cause of inflammation. However, an association with GERD could only be documented in less than two-thirds of the patients, suggesting that additional pathogenetic factors must be considered.

Research frontiers

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an emerging inflammatory esophageal disorder that can cause fibrosis with thickening of the esophageal mucosa, submucosa and muscularis. Therefore, EoE as a pathogenic factor for the development of SRs would support the “inflammation theory”. However, the causal relationship between SRs and EoE in adults is controversial.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Recent reports have demonstrated an association of SRs with EoE in children. The present study shows that a significant proportion of adult patients with SRs also exhibit EoE and that endoscopic findings are not reliable for supporting a diagnosis of EoE. Furthermore, predictors of an association of SRs with EoE were younger age, presence of dysphagia or food impaction, narrow rings and a history of allergies.

Applications

The study results suggest that esophageal biopsies should be obtained, not only in the presence of typical endoscopic signs for EoE, but also whenever a SR is detected in symptomatic patients, especially if the ring is narrow and if the patient is younger and has a history of allergies.

Peer review

This paper enrolled one hundred seventy-one patients with endoscopically diagnosed SRs who were prospectively registered and followed. EoE was diagnosed in 9% of the patients with SRs, some of whom did not present with typical endoscopic features of EoE. Therefore esophageal biopsies are warranted in patients presenting with SRs, not only in the presence of endoscopic findings suggestive of EoE, but also whenever a SR is detected.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Frank Zerbib, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Hopital Saint Andre, CHU de Bordeaux, 1 rue Jean Burguet, 33075 Bordeaux Cedex, France; Seng-Kee Chuah, MD, Division of Hepatogastroenterology, Chang Kaohsiung Gang Memorial Hospital, 123, Ta-Pei Road, Niaosung Hsiang, Kaohsiung 833, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Schatzki R, Gary JE. Dysphagia due to a diaphragm-like localized narrowing in the lower esophagus (lower esophageal ring) Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1953;70:911–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyting WS, Baker GM, Mccarver RR, Daywitt AL. The lower esophagus. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1960;84:1070–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schatzki R. The lower esophageal ring. Long term follow-up of symptomatic and asymptomatic rings. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;90:805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall JB, Kretschmar JM, Diaz-Arias AA. Gastroesophageal reflux as a pathogenic factor in the development of symptomatic lower esophageal rings. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1669–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ott DJ, Ledbetter MS, Chen MY, Koufman JA, Gelfand DW. Correlation of lower esophageal mucosal ring and 24-h pH monitoring of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckardt V, Dagradi AE, Stempien SJ. The esophagogastric (Schatzki) ring and reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1972;58:525–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, Husain K, Buonomo C, Fox VL, Antonioli D, Fortunato C, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of Schatzki ring with eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:436–441. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200404000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackenzie SH, Go M, Chadwick B, Thomas K, Fang J, Kuwada S, Lamphier S, Hilden K, Peterson K. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia--a prospective analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sgouros SN, Bergele C, Mantides A. Schatzki’s rings are not associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:535–536; author reply 536. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katzka DA. Eosinophil: the new lord of (esophageal) rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:802–803. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal RK, Glancy JJ, Spiro HM. Lower esophageal ring. 1. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:1298–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197006042822305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright RA, Hurwitz AL. Relationship of hiatal hernia to endoscopically proved reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24:311–313. doi: 10.1007/BF01296546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobin RW. Esophageal rings, webs, and diverticula. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:285–295. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199812000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odze RD. Pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis: what the clinician needs to know. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:485–490. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parfitt JR, Gregor JC, Suskin NG, Jawa HA, Driman DK. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: distinguishing features from gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study of 41 patients. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:90–96. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer P. Frequency of the asymptomatic lower esophageal contractile ring. N Engl J Med. 1956;254:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195604122541503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVault KR. Lower esophageal (Schatzki’s) ring: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Dig Dis. 1996;14:323–329. doi: 10.1159/000171563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YM, Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Munitz HA. Multiphasic examination of the esophagogastric region for strictures, rings, and hiatal hernia: evaluation of the individual techniques. Gastrointest Radiol. 1985;10:311–316. doi: 10.1007/BF01893119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott DJ, Chen YM, Wu WC, Gelfand DW, Munitz HA. Radiographic and endoscopic sensitivity in detecting lower esophageal mucosal ring. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:261–265. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, DeMeester SR, Hagen J, Lipham J, DeMeester TR, Chandrasoma P. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scharschmidt BF, Watts HD. The lower esophageal ring and esophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1978;69:544–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Walker MM, Agréus L. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: the population-based Kalixanda study. Gut. 2007;56:615–620. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, Baker TP, Maydonovitch C, Lake JM, Wong RK, Osgard EM. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in an adult population undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohm M, Richter JE. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: overview, current limitations, and future direction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2635–2644; quiz 2645. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasha SF, DiBaise JK, Kim HJ, De Petris G, Crowell MD, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK. Patient characteristics, clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a case series and systematic review of the medical literature. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peery AF, Cao H, Dominik R, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Variable reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light and narrow-band imaging for patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sgouros SN, Bergele C, Mantides A. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: what is the clinical significance? Endoscopy. 2006;38:515–520. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Croese J, Fairley SK, Masson JW, Chong AK, Whitaker DA, Kanowski PA, Walker NI. Clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:516–522. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)01870-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, Heer P, Simon HU, Zwahlen M, Beglinger C, Schoepfer AM. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–1350.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitellas KM, Bennett WF, Bova JG, Johnston JC, Caldwell JH, Mayle JE. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis. Radiology. 1993;186:789–793. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.3.8430189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan S, Orenstein SR, Di Lorenzo C, Kocoshis SA, Putnam PE, Sigurdsson L, Shalaby TM. Eosinophilic esophagitis: strictures, impactions, dysphagia. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:22–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1021769928180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]