Summary

From the very early days of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) research, it was recognized that different protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms might be involved in the activation of NF-κB. Pharmacological tools and pseudosubstrate inhibitors suggested that these kinases play a role in this important inflammatory and survival pathway; however, it was the analysis of several genetic mouse knockout models that revealed the complexity and interrelations between the different components of the PB1-network in several cellular functions, including T-cell biology, bone homeostasis, inflammation associated with the metabolic syndrome, and cancer. These studies unveiled, for example, the critical role of PKCζ as a positive regulator of NF-κB through the regulation of RelA but also its inflammatory suppressor activities through the regulation of the interleukin-4 signaling cascade. This observation is of relevance in T cells, where p62, PKCζ, PKCλ/ι, and NBR1 establish a mesh of interactions that culminate in the regulation of T-cell effector responses through the modulation of T-cell polarity. Many questions remain to be answered, not just from the point of view of the implication for NF-κB activation but also with regard to the in vivo interplay between these pathways in pathophysiological processes like obesity and cancer.

Keywords: PKC, NF-κB, p62, Par-4, osteoclastogenesis, carcinogenesis, inflammation

Introduction

The protein kinase C (PKC) family of proteins is a group of serine/threonine kinases that encompasses around 2% of the human kinome and forms a part of the AGC kinases, along with protein kinase A and protein kinase G (1). PKCs are highly conserved in eukaryotes with different species showing divergent complexity, ranging from one isoform in S. cerevisiae to 12 in mammals (2). All of these isoforms share a highly conserved catalytic domain and a more divergent regulatory domain at the N-terminus. These relatively conserved domains are linked through more variable hinge regions. The regulatory domain contains different structural domains that influence the sensitivity of each PKC to different stimuli, as well as their mechanism of regulation and function. There are layers of complexity and variations from one isoform to the other, but the pioneering work of Nishizuka and others in the early 1980s (3, 4) provided the basic framework for understanding the activation and structural properties of this family of kinases.

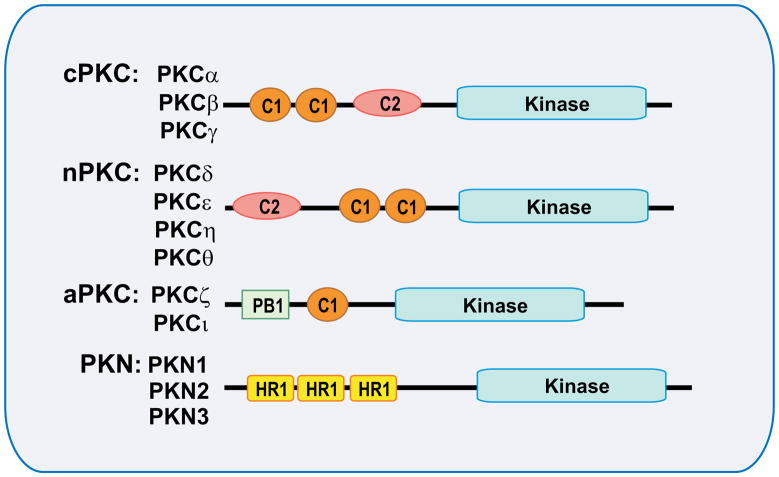

The 12 mammalian PKC genes can be subdivided into four distinct subgroups based on the different topology of their regulatory domains (Fig. 1): the conventional or classical (cPKCs), the novel (nPKCs), the atypical (aPKCs), and the PKN group. The cPKCs include PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCγ and have a conserved region 1 (C1) as a tandem repeat that is structurally a double zinc-finger and a binding pocket for the PKC effector diacylglycerol (DAG) and phospholipids (5,6). They also contain a C2 domain that makes this subfamily responsive to calcium (7). The nPKCs comprise PKCδ, PKCε, PKCη, and PKCθ. Similar to the cPKCs, the novel PKCs are activated by DAG and phospholipids, but they are calcium-independent. The aPKCs include PKCζ and PKCι (also known as PKCλ in mice). They are insensitive to calcium and DAG, most likely due to the lack of a C2 domain and to the single zinc-finger structure of the C1 domain. This group also contains a distinct structural domain called Phox/Bem 1 (PB1) at the N-terminus that is specific for this subfamily and that links these two isoforms (ζ and ι) to a network of PB1-containing proteins (8, 9) (see below). The PKN subfamily members (PKN1, PKN2 and PKN3) possess three leucine-zipper-like heptapeptide repeat 1 domains (HR1) at their regulatory region, which bind Rho-GTP and regulate phosphorylation by PDK1 (10).

Fig. 1. Structure of the protein kinase C (PKC).

Schematic representation of the different PKC subfamilies and their domain structural organization. The PKC family is divided into four structurally and functionally distinct subgroups according to their regulatory domains: the classical isoforms (cPKC), novel isoforms (nPKC), atypical isoforms (aPKC) and the PKC-related kinases (PKN). Conserved region 1 (C1) confers binding to diacylglycerol and phospholipids, and C2 senses calcium. PB1 (Phox/Bem domain 1) is specific of aPKC and acts as a dimerization domain. Homology region 1 (HR1) confers small-GTPase binding properties to PKN.

Activation of PKCs

The mechanisms involved in PKC activation have been extensively studied (11, 12). The current model proposes that, when inactive, PKC is auto-inhibited by its pseudosubstrate (an isoform-specific sequence present in the regulatory domain), which blocks the substrate-binding pocket in the kinase domain (13). This inactive state is preceded by a priming process through a series of serine/threonine transphosphorylation and autophosphorylation events that are required for maturation and stabilization (11, 12). To achieve a competent state, the kinase domain has to be phosphorylated on three (cPKCs and nPKCs) or two (aPKCs and PKNs) Ser or Thr sites, which stabilize the active kinase conformation. This process seems to require two upstream kinases. One is phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) to phosphorylate the activation loop in the kinase domain (14), and the other is the mammalian target of rapamycin 2 complex (mTORC2), which regulates phosphorylation of the turn motif and hydrophobic sites (when present) in the C-terminal tails of these kinases (15, 16). In the case of aPKCs and PKNs, an acidic phosphomimetic Asp or Glu is present in the hydrophobic motif instead of a phosphorylatable Ser or Thr. This acidic residue seems to bind the PDK-1-interacting fragment (PIF) pocket of PDK1, bypassing the requirement for the hydrophobic site phosphorylation (17, 18). Other regulatory or scaffolding components probably exist to regulate access to the PIF.

The activation step takes place in response to the binding of lipid second messengers, allosteric effectors, or both, to specific domains at the regulatory region depending on the isotype. For those PKCs activated by DAG (cPKCs and nPKCs), increases in plasma-membrane DAG levels trigger the intracellular relocalization and activation. Sources of DAG include tyrosine-kinase receptor or G-protein-coupled receptor activation through the stimulation of phospholipase γ (PLCγ) or PLCβ. There are other less well-characterized mechanisms to generate DAG, such as the combined action of phospholipase D (PLD) and phosphatidic acid hydrolase (PAP). PLCs produce the membrane lipid DAG and the soluble messenger inositol triphosphate upon cleavage of phosphoinositide 4,5-biphosphate. Increased DAG levels reversibly recruit cPKCs and nPKCs to the membrane through their zinc-finger (C1) domains (19). This membrane recruitment is generally considered as the primary event for cPKC and nPKC activation, although it does not fully explain the diverse intracellular localization of the different isoforms (20). Other protein modifications, such as tyrosine phosphorylation or proteolysis, might also be critical factors in mediating PKC activation (19).

The aPKCs, which cannot be activated by DAG, have been suggested to be sensitive to other lipids such as phosphatidylinositols (PIs) (21), phosphatidic acid (22), arachidonic acid, and ceramide (23, 24). In addition, interaction with specific binding partners could be an important mechanism to modulate activation and to confer spatial and temporal specificity to otherwise promiscuous kinases. For example, the C1 domain of the aPKCs that harbors a zinc-finger binds the protein Par-4, which blocks aPKC enzymatic activity (25). Par-4 is, therefore, a specific inhibitor of the aPKCs, most probably because its binding to the zing-finger competes with other stimuli. The other site for modulation by adapters is the PB1, but binding to this domain primarily affects localization and not the enzymatic activity of the aPKCs (26).

The PB1-domain network

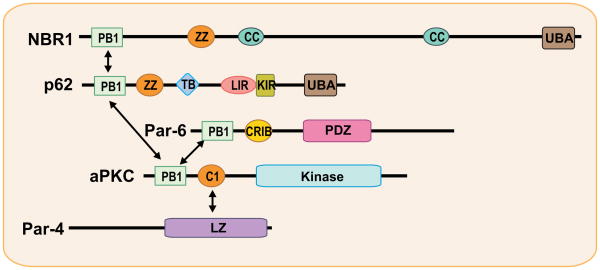

The PB1 protein-protein interaction domain is unique to the aPKC subfamily of PKCs (Fig. 1). The identification of this domain has opened new avenues for exploring the specific functions of these kinases. Each adapter and regulator that has been found to interact with the PB1 domain sheds light on the physiological roles of the aPKCs. The PB1 domain is a modular scaffold domain, named after the prototypical domains found in Phox and Bem1p, which mediates polar heterodimeric interactions (8, 27). Besides the aPKCs, PB1s are found in adapter/scaffold proteins (such as p62, NBR1, and Par-6), and also in other kinases of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, including MEK5α and MEKK3. This domain comprises about 80 amino acid residues and is conserved among animals, fungi, and plants. The human genome contains at least 13 PB1-containing proteins. Structurally, PB1 domains display the topology of a ubiquitin-like-β-grasp fold and are grouped into three types: type I (or type A), type II (or type B), and type I/II (or type AB) (9). The type I domain group contains a conserved acidic DX(D/E)GD segment (called the OPCA motif) that interacts with a conserved lysine residue of a type II domain. Type I includes the PB1 domains of p40phox, MEK5, and NBR1, whereas type II occurs in p67phox, Par-6, MEKK2, and MEKK3. The type I/II PB1 domain, containing both the OPCA motif and the invariant lysine, is present in the aPKCs, p62, and TFG (8). Heterodimeric assembly occurs between type I and type II PB1 domains and is considered to be a cellular mechanism for imposing spatial and temporal specificity during signaling (Fig. 2). The dimerization involves specific electrostatic interactions between the conserved acidic region of the OPCA motif from a type I domain with the conserved Lys residue from a type II domain. In addition, type I/II domains can homodimerize, at least theoretically. Indeed, p62 forms homo-oligomers, although such self-association has not been described for the aPKCs or other proteins with this type of PB1 (28, 29).

Fig. 2. The atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) signaling platform.

Schematic showing domain organization and network signaling mediated by aPKC and their adapters and regulators. The aPKCs interact with the PB1-containing adapters p62 and Par-6 to regulate specific functions. The scaffold p62 binds NBR1, a highly structurally related molecule with similar domain organization. Par-4 is a regulator and inhibitor of the aPKCs through binding to their C1 domain. C1, conserved region 1; PB1, Phox/Bem domain 1; LZ, leucine zipper; CRIB, Cdc42/Rac interactive binding; PDZ, PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1; ZZ, ZZ-type zinc finger; TB, TRAF6-binding; LIR, LC3-interacting region; KIR, Keap-interacting region; UBA, ubiquitin-associated; CC, coiled coil.

p62 and Par-6 are selective adapters for the aPKCs (30–33). Par-6 has been shown to be central to the control of cell polarity and, through its PB1 domain, allocates the aPKCs specifically in polarity-related functions. The p62/aPKC signaling platform plays a critical role in NF-κB activation (34). p62 interacts with PKCζ and PKCι, but not with any of the other closely related PKC family members. It is not a substrate and does not seem to significantly affect the intrinsic kinase activity of the aPKCs (33). A p62 ortholog has been identified in C. elegans (T12G3.1) and in Drosophila [Ref(2)P], with both of these containing a conserved PB1 domain (35, 36). Moreover, p62 harbors a number of domains that support its role as a scaffold in aPKC signaling (34). Thus, the formation of aPKC complexes with different adapters, scaffold proteins, and regulators, such as Par-6, p62, and Par-4, serves to confer specificity and plasticity to the actions of these kinases and to establish a signaling network (37). However, the factors that determine which complex is formed at a given time remain to be identified.

Personal and historical narrative

Early studies on NF-κB activation by aPKCs

The initial studies on the role of the aPKCs in NF-κB signaling were done in our laboratory back in the 1990s and used Xenopus laevis oocytes as the model system (38). We designed the first peptides against the pseudosubstrate sequence to selectively block the activity of the different PKC isoforms (39). This strategy was later broadly used incorporating myristoylated forms of the peptides to achieve cell permeability. Until that time, most of the experimental approaches to studying the PKCs involved their purported downregulation by chronic treatment with phorbol esters. However, it later became apparent that this strategy does not affect the aPKCs, because they do not bind phorbol esters. By using microinjection of specific inhibitor peptides into oocytes, we showed that an aPKC was required for insulin/Ras-induced NF-κB activation in Xenopus laevis (38). Subsequent transfection experiments using kinase-defective dominant-negative mutants, overexpression experiments, or antisense approaches further supported a role for the aPKCs in the control of NF-κB activation (40–45).

These early studies were intended to establish the differential role of this subfamily of PKCs as a new pathway linked to NF-κB, and efforts were aimed at understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of these isotypes on the NF-κB cascade, as well as the level at which the effect was manifested. Initial reports suggested that PKCζ was upstream of the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) and able to bind the IKKβ to modulate its activation (46, 47). Later results using gene-deficient mice confirmed these initial observations while at the same time revealing a more complex and, most probably, tissue-specific role. Thus, PKCζ is required for IKK activation in the lung in response to tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), but not in fibroblasts, in which its main function is to regulate NF-κB transcriptional activity at the level of RelA phosphorylation (48, 49).

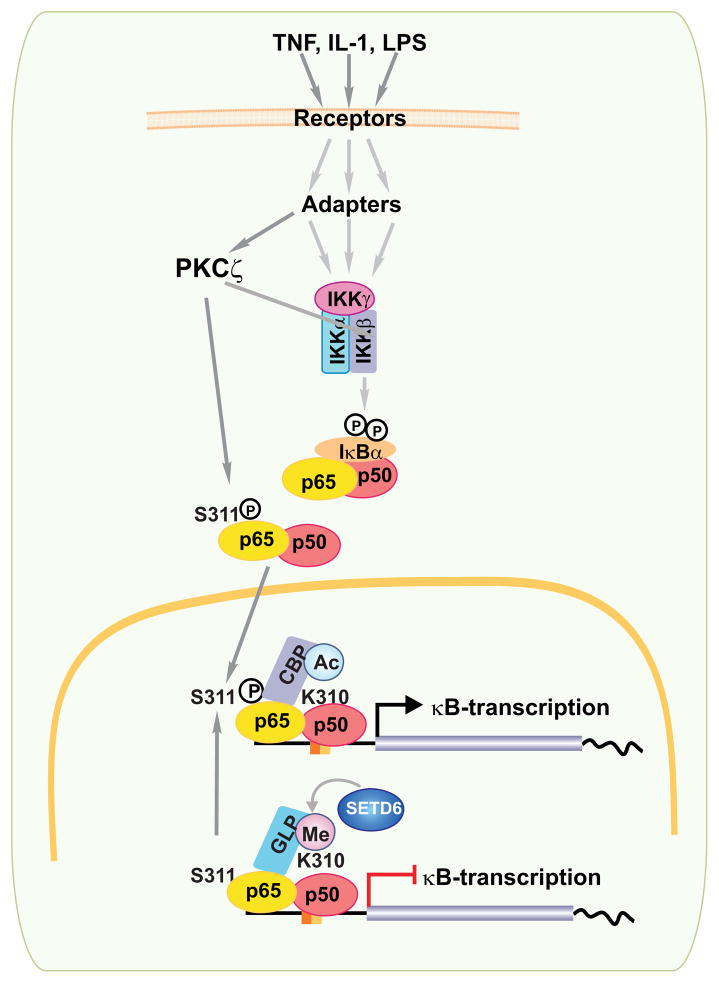

Transcriptional control of NF-κB by PKCζ: Ser311

NF-κB regulates the expression of thousands of genes; thus, mechanisms need to be in place to fine-tune a process that is initially controlled by an all-or-nothing nuclear translocation pathway (50, 51). Results from several laboratories including ours (52–54) show that phosphorylations of the RelA subunit of the NF-κB complex fulfill that purpose. Under basal conditions, dimers of p50 NF-κB subunits are bound to gene regulatory elements in the chromatin. This prevents undesired uncontrolled activity by recruiting histone deacetylase (HDAC), which keeps the expression of κB-dependent genes inhibited in the absence of stimuli due to the deacetylation of histones (55). According to the model put forward by Ghosh and co-workers (52, 55, 56), RelA is phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA) and/or mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase at Ser276 once p50-RelA heterodimers are released from IκB. This promotes the interaction of RelA with the transcriptional coactivator CBP (55). This interaction results in increased CBP-mediated histone acetylation, which in turn results in the generation of an ‘open’ permissive chromatin structure that allows the full transcriptional activity of the NF-κB complex (55). In addition to RelA serine 276 phosphorylation, serine 311 is also phosphorylated in response to TNFα(49). This serine residue is specifically targeted by PKCζ, which has been shown, through genetic manipulations, to be required for full NF-κB transcriptional activity in vivo and in cell culture experiments (57). Interestingly, both phosphorylation residues reside in the Rel homology dimerization domain (RHD) and are required for the recruitment of CBP (49, 52).

Phosphorylation of serine 311 occurs in a region proximal to the site where other post-translational modifications take place to modulate the strength and duration of NF-κB nuclear activity (58, 59). Among these modifications, acetylation of Lys310 is one the best characterized (50). It is required for the full transcriptional potential of NF-κB and is important for modulating NF-κB-dependent inflammatory response (50, 60). In addition, Lys 314 and 315 are methylated by SET9 to terminate the NF-κB signal (61, 62). Both acetylation and methylation have been shown to have a functional interplay with phosphorylation to fine tune transcriptional activation. Thus, for example, acetylation of Lys310 is blocked in the absence of Ser276 phosphorylation, as this phosphorylation event is required to recruit CBP/p300 and allow acetylation at Lys 310 (63). In addition, acetylation at this residue impairs methylation of Lys 314 and 315, which are important events for the ubiquitination and degradation of chromatin-associated RelA (59). Recent results show another layer of control via crosstalk between phosphorylation of serine 311 and monomethylation at lysine 310 (64). An unbiased screening of human protein lysine methyltransferases led to the discovery of SET domain-containing 6 (SETD6) as the methyltransferase responsible for the monomethylation of chromatin-associated RelA at lysine 310 (64). Importantly, the methylated form of RelA resides in a histone H3-rich region near the promoters of several NF-κB genes, which suggests that methylated RelA represses gene expression under basal conditions (65). Consistent with this hypothesis, the inactivation of SETD6 leads to increased κB-dependent transcription under basal conditions and, importantly, under stimulated conditions as well (64). These observations indicated that the lysine 310-serine 311 sequence could be a ‘hotspot’ for the transcriptional regulation of NF-κB by chromatin acetylation-methylation. Methylated lysine 310 binds a protein termed GLP, which along with its partner G9a, promotes the methylation of H3 at lysine 9 in chromatin regions with repressed transcription (66). Therefore, lysine 310 methylation of RelA by SETD6 under basal conditions results in the recruitment of GLP, which methylates histone H3 and consequently keeps chromatin in a ‘closed’ state incompatible with active transcription (64). When cells are incubated with TNF, GLP is released; the chromatin is ‘opened’ and efficient activation of κB-dependent gene transcription takes place (Fig. 3). The role of PKCζ in this model is critical because its activation in TNF-treated cells leads to the phosphorylation of serine 311, which displaces GLP from RelA allowing the demethylation of chromatin and the ensuing enhanced transcription of κB-genes (64). A recent study in which the SETD6-RelA peptide complex structure was determined suggests a structural basis for the methyl-phospho switch between Lys310 and Ser311 to regulate the localized chromatin state and gene expression (67). In summary, the PKCζ-mediated phosphorylation of serine 311 promotes the opening of chromatin by increasing its acetylation, mediated by CBP recruitment, and inhibiting its methylation through the release of GLP from methylated lysine 310. These are important observations, but the physiological significance of lysine 310 methylation and serine 311 phosphorylation in vivo still needs to be determined at an organismal level by analyzing knockin mice with point mutations in those sites. In addition, more mechanistic details are necessary for a detailed understanding of the precise molecular mechanism whereby phosphorylated serine 276 and serine 311 cooperate to recruit CBP, as well as how the phosphorylation of serine 311 controls the functional interaction of SETD6 and GLP with RelA. In any case, a role for this new pathway in inflammation has been demonstrated in genetically PKCζ-deficient cells, which are incapable of an adequate inflammatory response to TNF and IL-1. Moreover, this pathway also appears to play a role in cancer, as a reduction in SETD6 in transformed cells led to increased tumorigenic potential in vitro and in vivo (64). The possible correlation of SETD6 or GLP levels with tumor patient survival as well as the existence of potential mutations in lysine 310 or the hyperphosphorylation of serine 311 in patient tumor samples needs to be determined to establish the relevance of these novel modifications to human cancer.

Fig. 3. Role of PKCζ in NF-κB activation.

The binding of different ligands to their respective receptors in the plasma membrane triggers the recruitment of specific adapters for each receptor that orchestrate the formation of a signalosome complex that includes two catalytic (IKKα and IKKβ) and one regulatory subunit (IKKγ). This complex phosphorylates IκB, which is subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded through the proteasome system, releasing NF-κB (the more classical components of which are p65-p50 heterodimers), which is free now to translocate to the nucleus and interact with elements in the promoter of inflammatory and survival genes harboring κB-elements in their promoters. PKCζ phosphorylates p65 at Serine 311 (S311), an important residue for recruiting the CBP coactivator complex. This event promotes acetylation of Lysine 310 (K310) to activate transcription. Under basal conditions, p65 is methylated (Me) at K310 by SETD6, promoting recruitment of GLP, which leads to the repression of κB-dependent transcription. Upon ligand binding, phosphorylation of S311 by PKCζ blocks methylation to activate the system. Depending on tissue specificity PKCζ could also act as an IKK kinase.

The aPKC pathway in the control of NF-κB in Drosophila

The NF-κB pathway is remarkably conserved in Drosophila and is critical for the control of the innate immune response (68). The RelA homologs in Drosophila, dorsal-related immunity factor (Dif) and dorsal, are essential for the synthesis of the antimicrobial peptide drosomycin in response to the activation of the Toll pathway by fungal pathogens (69, 70). Both dorsal and Dif are retained in the cytosol by the IκB homologue cactus, whose phosphorylation and subsequent degradation release these transcription factors allowing their translocation to the nucleus (69, 70). Parallel to the Toll pathway, there is a another pathway in Drosophila that involves the kinase dTAK1, which serves to control the degradation of relish (70). Relish is the fly homolog of NF-κB1/NF-κB2 and is required for the synthesis of immune response proteins, namely antimicrobial peptides, including diptericin (69). Interestingly, knocking down the Drosophila aPKC (DaPKC) ortholog with RNA interference (RNAi) in Schneider cells inhibits drosomycin expression but not that of diptericin, indicating that DaPKC is located specifically in the Toll antifungal pathway (35). DaPKC knockdown does not affect cactus or relish degradation but does inhibit drosomycin transcriptional activity (35). Furthermore, DaPKC phosphorylates Dif, the fly homolog of RelA, which suggest a conserved role for the aPKCs in the regulation of NF-κB transcriptional activity (35). In this regard, the p62 ortholog, Ref(2)P binds not only DaPKC but also the fly homologue of TRAF6 (dTRAF2). Overexpression of Ref(2)P is sufficient to activate drosomycin, and its depletion severely impairs Toll signaling, which is more evidence for the conservation of the aPKC pathway and the importance of this kinase in the regulation of NF-κB and the innate immune response (35, 71).

Proof of concept and new pathways unveiled in knockout mice

The phenotypic analysis of PKCζ-deficient mice confirmed the role of PKCζ in the control of NF-κB in vivo in the immune system, specifically in B cells (57). The first indication of such a role came from the analysis of PKCζ total knockout (KO) mice. These mice displayed alterations in the development of secondary lymphoid organs, showing morphological defects in the spleen’s marginal zone and Peyer’s patches, and a reduced percentage of mature B cells (72, 73). Interestingly, this correlated with deficient B-cell survival and proliferation in response to B-cell receptor activation but not to the stimulation of other receptors (73). In vivo, PKCζ deficiency resulted in an impaired adaptive response with significant decreases in the production of immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgA. With regard to the phenotype of PKCζ-deficient T cells (see below), there were also deficiencies in IgE (73). Biochemically, it was found that expression of at least three κB-dependent genes was impaired in PKCζ-deficient B cells in response to B-cell receptor (BCR) activation, with little or no changes in the nuclear translocation of NF-κB (73). This observation is consistent with the notion that PKCζ does not control IKK activation, except in the lung where PKCζ is abundantly expressed, or in overexpression experiments. Instead, it controls the regulation of NF-κB transcriptional activity by phosphorylation of serine 311 (49, 72).

The role of PKCζ in B-cell proliferation and NF-κB activation contrasts with the lack of effect of PKCζ deficiency on T-cell proliferation (73). However, our data showed that PKCζ KO does have a measurable and reproducible effect on T-cell differentiation towards the T-helper 2 (Th2) lineage (74). We found that the loss of PKCζ impaired the in vitro polarization to Th2 without effecting Th0 or Th1 differentiation (74). Interestingly, we also observed defects in the activation of GATA3, a hallmark or Th2 differentiation (75). The nuclear translocation of RelA was also impaired in PKCζ-deficient cells (74). However, since the activation of other transcription factors such as c-Maf and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (Stat6) was also impaired, this strongly suggested that the role of PKCζ was not restricted to NF-κB activation during Th2 differentiation but, rather, that PKCζ was playing a more fundamental role in this process. Consistent with this idea, we found that PKCζ was important for IL-4 signaling, which, along with signals emanating from the T-cell receptor (TCR), is essential for the activation of the Th2 differentiation program (74). We showed that Stat6 phosphorylation in response to IL-4 stimulation was impaired even in mature, undifferentiated, PKCζ-deficient T cells as compared with their wildtype (WT) controls (74). The precise mechanism has not been totally clarified, but it has been shown to involve the recruitment of PKCζ to the activated IL-4 signaling complex and the direct phosphorylation of Janus kinase 1 (Jak1) by PKCζ, which modulates Jak1 activation to phosphorylate Stat6 (76). These observations have important repercussions in vivo. For example, PKCζ deficiency impaired the ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice, a typical in vivo Th2 response (74). Adoptive transfer experiments demonstrated that this effect was not due to PKCζ deficiency in the stroma but, instead, to a genuine autonomous T-cell effect (74). Collectively, these observations unveiled a previously unanticipated role for PKCζ in a pathway separate from the NF-κB pathway. The fact that PKCζ is also important in IL-4 signaling indicates that it is a versatile kinase that influences processes in addition to the inflammatory response.

The novel role for PKCζ in IL-4 signaling is also important in T-cell–mediated fulminant hepatitis, another physiologically relevant in vivo response. The discovery of the role for PKCζ in this pathological situation came from analyzing the effects of PKCζ deficiency in mice injected with concanavalin A (ConA), a well-established model of fulminant hepatitis (77). Previous studies have suggested that the activation of NF-κB was a suppressor of liver apoptosis in fulminant hepatitis (78, 79). However, in contrast to expectations, even though PKCζ-deficient mice showed impaired NF-κB activation in the liver, which should have resulted in impaired survival, they showed reduced damage to the liver and a healthier state than their WT controls (76). This finding indicated that even though PKCζ is required for NF-κB activation, it must play an additional role in a pathway required for T-cell–induced hepatitis. Interestingly, we showed that the loss of PKCζ inhibited the induction of serum IL-5 and liver eotaxin, two important mediators of liver damage (76). As eotaxin is synthesized by hepatocytes and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, whereas IL-5 is produced by natural killer T (NKT) cells, these results imply that the loss of PKCζ affects the function of both liver and NKT cells. The adoptive transfer of PKCζ-deficient liver mononuclear cells (including a large proportion of NKT cells) into PKCζ KO mice was unable to restore ConA-induced hepatitis, whereas the adoptive transfer of WT mononuclear cells into PKCζ-deficient mice did restore liver damage (76). This outcome is similar to the Stat6−/− mouse phenotype (80), thus supporting the idea that PKCζ is a physiologically relevant regulator of Stat6. We also observed more liver damage in PKCζ-deficient mice under these conditions, as compared with WT mice, due to the inhibition of NF-κB, which deprived the liver of its protecting signals (81). Taken together, these findings reinforce the notion that PKCζ plays a physiologically relevant role as a dual regulator of NF-κB and Stat6.

Mice in which the negative regulator of aPKC, Par-4, had been knocked out revealed a phenotype biochemically consistent with the aPKCs being responsible for an important step in NF-κB activation. Embryo fibroblasts from Par-4–deficient mice displayed increased NF-κB activation and decreased stimulation of C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (82, 83). Interestingly, when the immunological phenotype of these mutant mice was analyzed, it was clear that Par-4 deficiency resulted in an increased proliferative response of peripheral T cells when challenged through the TCR, accompanied by enhanced cell cycle entry and inhibition of apoptosis, with augmented IL-2 secretion (84). From a biochemical point of view, the TCR-triggered activation of NF-κB was increased, resulting in a corresponding increase in IL-4 production. These results are in good agreement with Par-4 inhibiting the ability of PKCζ to modulate the IL-4 signaling pathway and Th2 differentiation, and with a role for the aPKCs in NF-κB activation and mature T-cell proliferation (74, 84). However, they contrast with our observations that the loss of PKCζ does not affect mature T-cell proliferation or NF-κB activation (85). These paradoxical findings could be explained by the fact that Par-4, in addition to targeting PKCζ in T cells, would also inhibit PKCλ/ι, the latter being responsible for the enhanced proliferative effects of Par-4-deficient mature T cells.

To address this important question, we analyzed the phenotype of mice in which PKCλ/ι was selectively ablated in activated T cells. For this study, we crossed PKCλ/ιfl/fl mice with CreOX40 mice in which the expression of Cre was under the control of the Tnfrsf4 locus (86). OX-40 is expressed almost exclusively in activated T cells, especially CD4+ cells, only upon stimulation (86). This strategy resulted in a mutant mouse line in which PKCλ/ι was expressed at normal levels in immature thymocytes and naive T cells and, as predicted, was deleted only upon T-cell activation, thus avoiding embryonic lethality and preventing potential confounding effects resulting from the deletion of PKCλ/ι during development or in resting cells (87). Surprisingly, these mice did not show a proliferative defect, but like PKCζ-deficient mice, they had impaired Th2 differentiation in vitro and in vivo in the disease model of ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation (87). However, and again surprisingly, the mechanism whereby PKCλ/ι impinged on the Th2 differentiation program was quite different from that of PKCζ. PKCλ/ι, in contrast to PKCζ, was not required for IL-4 activation of Stat6. Rather, its genetic ablation led to a global shutdown in the activation of a myriad of Th2-relevant transcription factors such as nuclear factor for activated T cells (NFAT), NF-κB, and Stat6, in addition to the master regulatory gene in Th2 differentiation, GATA3 (87). These results indicated that PKCλ/ι, whose levels, like those of PKCζ, are increased during Th2 differentiation, affects some fundamental T-cell function that, when impaired, results in a global inhibition of transcriptional signaling.

One fundamental T-cell function that could be affected by the loss of PKCλ/ι is T-cell polarity, a mechanism essential for T-cell activation and in which the aPKCs have been genetically implicated in lower organisms (88, 89). Of great functional relevance in this regard, we showed that the ability of the polarity marker Scribble to localize to one of the poles of the activated T cell was severely impaired in PKCλ/ι-deficient T cells (87). Also, the asymmetric polarization of CD44 relative to CD3 was diminished in the mutant T cells, as was the proper localization of Crtam, another recently discovered marker of late polarization (87). Collectively, these results indicate that PKCλ/ι deficiency in activated T cells leads to impaired polarity during late T-cell activation, which results in a general shutdown of the Th2 transcriptional machinery. Therefore, although PKCλ/ι is a direct upstream IKK kinase in vitro (47) and PKCζ is necessary for the activation of NF-κB transcriptional activity by phosphorylation of serine 311 in vitro and in vivo (49, 72), the role of PKCλ/ι in vivo, at least in T cells, is more complex and related to the role in regulating cell polarity for the aPKCs that was suggested in lower organisms. This role seems to be restricted to PKCλ/ι since the loss of PKCζ had no effect on T-cell polarity, although it was essential for IL-4 signaling towards Stat6 in Th2 differentiation (74, 87).

PKCζ, an anti-inflammatory signaling molecule in adipocytes

The fact that PKCζ plays a critical role in IL-4 signaling is relevant to asthma as well as other pathological situations. Recently, we found that PKCζ is an important anti-inflammatory molecule in obesity-induced inflammation and the ensuing insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (90). These findings are based on studies highlighting the importance of adipose tissue inflammation in the induction of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance during obesity (91–95). Interestingly, the genetic inactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorγ (PPARγ) or PPARδ in macrophages prevented the alternative activation of macrophages (type 2), which resulted in a tonic type 1 hyperinflammatory state, and the ensuing glucose intolerance and insulin resistance during obesity (96, 97). There are, however, other scenarios, such as in JNK-deficient mice, in which inflammation is orchestrated by the adipocytes, which control the inflammation-induced insulin resistance in the liver through the generation of IL-6 (93). It is likely, depending on the different signaling pathways, that the hematopoietic system, the stroma, or both are responsible for these processes. Our data showed that PKCζ KO mice exhibit a hyperinflammatory state during obesity that correlates with a glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. In addition, we showed that even though PKCζ is involved in the generation of M2 macrophages, PKCζ ablation in the non-hematopoietic compartment but not in the hematopoietic system was sufficient to drive inflammation and IL-6 synthesis in the adipose tissue, which, based on the phenotype of PKCζ/IL-6 double KO mice, accounts for insulin resistance during obesity (90). Therefore, PKCζ emerges as a positive regulator of NF-κB, and also as a as a critical negative modulator of IL-6 in the control of obesity-induced inflammation in adipocytes through its positive role in IL-4 signaling, which is also relevant in allergic responses and Th2 differentiation, as well as in T-cell mediated fulminant hepatitis.

aPKC adapters and NF-κB in T-cell activation and beyond

Our own work and that of others led to the identification of two PB1-containing scaffolds for the aPKCs: Par-6 and p62 (98). Par-6 has been implicated in the control of T-cell polarity in several systems (88). However, there is still no genetic in vivo evidence in mammals that it is actually relevant for T-cell polarity (88, 98). Our data showing that PKCλ/ι is, in fact, important in T-cell polarity suggest that Par-6 might also be functionally relevant to that function (87). Future studies should address this important function using conditional KO models such as that reported here for PKCλ/ι.

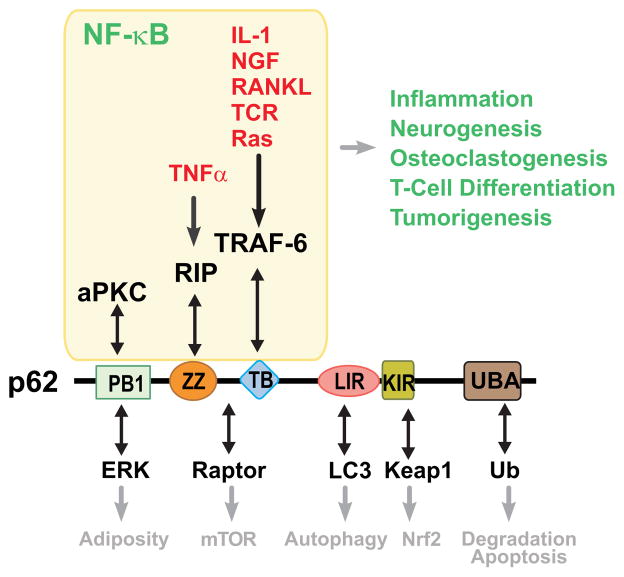

Because p62 binds both aPKCs, it is conceivable that it also plays a role in T-cell differentiation towards the Th2 lineage. Early studies from our laboratory using overexpression and anti-sense–mediated downregulation of p62 demonstrated that it is an important player in TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation owing to its ability to interact with the intermediary receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) (99). Of relevance for the in vivo phenotype of p62-deficient mice, we found that it binds TNF receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6), the IL-1 and LPS intermediary in the NF-κB pathway (100). It should be borne in mind that p62 is a complex scaffold protein that has several structural modules that serve to engage diverse signaling pathways (34) (Fig. 4). However, its ability to interact with TRAF6 is especially relevant from a pathophysiological point of view, due to the role of TRAF6 and NF-κB in bone remodeling through the control of osteoclastogenesis, and the fact that a series of well-defined mutations in p62 are associated with the Paget’s disease of bone (PDB), a genetic disorder characterized by aberrant osteoclastogenesis and bone homeostasis (101, 102). This is a pathway controlled by receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANK-L) that is essential for osteoclastogenesis (103). Of relevance for the role of p62 in NF-κB activation in vivo, we have shown that RANK-L triggers the formation of a p62-aPKC-TRAF6 complex in RAW 264.7 cells and primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (104). The in vitro and in vivo expression of p62 with a PDB mutation resulted in hyperactivated NF-κB and gain-of-function osteoclastogenesis, which is in agreement with the phenotype of the human disease (104–106). Mechanistically, p62 promotes its own oligomerization and that of TRAF6 leading to enhanced E3 ubiquitin-ligase activity that is important for NF-κB activation (107, 108). Of special relevance for T-cell biology, p62 levels are induced in T-cell differentiation, and its genetic ablation in mice results in impaired ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in vivo and Th2 differentiation ex vivo (109). Therefore, p62, similar to PKCζ and PKCλ/ι, emerges as an important component of the signaling cascades regulating Th2 function and asthma (74, 87, 109).

Fig. 4. p62 is a signaling hub.

Schematic showing domain organization and network signaling mediated by p62. The signaling adapter p62 is a critical mediator of important cellular functions owing to its ability to establish interactions with various signaling intermediaries. p62 plays a key role in NF-κB through specific binding to aPKC, RIP and TRAF6 to control inflammation, neurogenesis, osteoclastogenesis, T-cell differentiation and tumorigenesis. PB1, PB1 dimerization domain; ZZ, ZZ-type zinc finger; TB, TRAF6-binding; LIR, LC3-interacting region; KIR, Keap-interacting region; UBA, ubiquitin-associated.

The connection between p62 and NF-κB is also relevant in cancer (110). Levels of p62 are high in several human tumor types, especially in human lung cancers where more than 60% of lung adenocarcinomas and more than 90% of squamous cell carcinomas show elevated p62 protein levels (111). Consistent with a role for p62 in cancer through its ability to regulate the TRAF6-NF-κB axis, we showed that the loss of p62 in a Ras-inducible lung cancer mouse model resulted in resistance to carcinogenesis in this system, likely as a consequence of impaired Ras-induced TRAF6 and IKK activation and the ensuing stimulation of NF-κB (111). This led to increased ROS production by the p62-deficient cancer cell due to the lack of NF-κB-dependent ROS detoxifying enzymes, which resulted in enhanced apoptosis in Ras-expressing p62-deficient pneumocytes and fibroblasts (111). In addition to its role in lung tumorigenesis, p62 has also been shown to be involved in multiple myeloma (112). But in this case its actions are not in the tumor cell but in the stroma (112). That is, knocking down p62 in stromal cells from multiple myeloma patients abrogated the support of myeloma cell growth, as a consequence of reduced production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNFα, and RANK-L, which correlated with the inhibition of aPKC activity in the stromal cells (112). This finding suggests an unexplored role for p62 and the aPKCs in the tumor microenvironment, which is particularly relevant in light of new information implicating members of the NF-κB cascade in multiple myeloma.

Several studies have demonstrated that p62 interacts with NBR1, another PB1-containing adapter that cannot interact with the aPKCs (113). The modular organization of NBR1 is quite similar to that of p62, which suggests that they might be involved in similar pathways or even perform redundant functions. To address this question, our laboratory has generated an NBR1fl/fl mouse line that we have used to test the potential role of this protein in Th2 differentiation. As in the case of PKCλ/ι, NBR1 was selectively deleted in activated T cells and their ability to differentiate to Th2 cells was determined. Interestingly, like T cells deficient in PKCλ/ι, PKCζ, or p62, the genetic inactivation of NBR1 also led to impaired Th2 differentiation ex vivo and in vivo, as assessed by a reduced response to ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in vivo (114). From a mechanistic point of view, the loss of NBR1 did not affect NF-κB activation but did inhibit GATA3 as well as NAFTc1 and Stat6 activation (114). The effects on Stat6 were secondary to reduced IL-4 levels in the mutant T cells (114). However, NBR1 actions on NFATc1, although not yet totally defined, seemed to be more direct (114). Intriguingly, as for PKCλ/ι, the loss of NBR1 resulted in defects in T-cell polarity, which in contrast to PKCλ/ι deficiency, did not lead to NF-κB inhibition (114, 115). Therefore, subtle variations in the polarity complex give rise to different transcriptional signaling alterations all resulting in impaired Th2 differentiation and reduced allergic responses in vivo (114). Collectively, these studies highlight a very interesting link between T-cell polarity and transcriptional control. A key question is how these complexes interact to provide this important layer of gene expression control so critical for T-cell differentiation. The first aspect of this mechanism is the recruitment of the different players to the immunological synapse (IS) as part of the polarity process. In this regard, the loss of NBR1 had no effect on the recruitment of PKCλ/ι to the IS (114). Likewise, the genetic inactivation of PKCλ/ι did not affect the IS translocation of NBR1 (114). This observation is consistent with a model whereby NBR1 and PKCλ/ι are mutually independent. However, the translocation of p62 to the IS was dependent on NBR1 but independent of PKCλ/ι (114). Surprisingly, the translocation of PKCλ/ι was independent of p62, but that of NBR1 was not (114). Together, these results show that the likely interaction between p62 and NBR1 is required for their translocation to the IS, whereas the translocation of PKCλ/ι is independent of both adapters, which, likewise, translocate independently of PKCλ/ι. The second aspect of this mechanism is polarity itself determined by the recruitment of polarity markers such as scribble and talin to the IS. In this regard, it is clear from our previous data that the lack of NBR1 or p62 during T-cell activation leads to a significant reduction in the recruitment of these two polarity markers to the IS, indicating that upon T-cell activation, NBR1 is normally translocated to the IS, independently of PKCλ/ι but in conjunction with p62. This could explain why NBR1 or p62 deficiency leads to impaired polarity during late T-cell activation. It also implies that they are likely anchored to different adapters in the IS. Consistently, detailed biochemical studies demonstrated the interaction of PKCλ/ι with p62 as well as that of p62 with NBR1, but NBR1 was never shown to interact with PKCλ/ι (114). Therefore, although upon T-cell activation NBR1 and PKCλ/ι are able to interact with their common partner, they do not make direct contact with each other, even though both are located in the IS and both are critical for normal Th2 function. Although these observations establish for the first time the existence of a PB1 domain-mediated complex important for Th2 differentiation, there are still many unanswered questions with regard to how these complexes influence polarity and transcriptional activation through NF-κB or NFAT1c. It is expected that whereas the loss of p62 impairs NF-κB activation by the TCR, that of NBR1 does not, although both require each other to be recruited to the IS. Therefore, p62 must be in two different complexes binding either PKCλ/ι or NBR1 (114). At the IS, the two complexes would control different aspects of NFATc1 signaling. On the one hand, PKCλ/ι controls NFATc1 at the transcriptional level through the nuclear translocation of NF-κB (87), whereas NBR1 is likely to be responsible for the specific activation of NFATc1 in an NF-κB-independent manner (114).

Par-4, a negative regulator of NF-κB through the aPKCs

Our analysis of the phenotype of Par-4–deficient mice definitively tested the in vivo role of the aPKCs in NF-κB activation, at least in the immune response (84). The interaction of Par-4 with the zinc-finger domain of PKCζ, PKCλ/ι, or both resulted in repression of the enzymatic activity of both aPKCs that, in turn, provoked the inhibition of NF-κB function (82). Consequently, the loss of Par-4 in embryo fibroblasts from KO mice led to enhanced PKCζ and NF-κB activities, with functional repercussions on cell survival (83). However, possibly the most compelling evidence for the existence of a Par-4/aPKC cassette in the control of NF-κB in vivo came from the analysis of the immune response in mice deficient in Par-4 or doubly deficient in Par-4 and PKCζ, as compared to their WT counterparts and PKCζ single KO mice. First, we showed that Par-4 and PKCζ KO mice displayed opposite immunological phenotypes in vivo and ex vivo (73, 84). Whereas PKCζ-deficient mice were characterized by impaired B-cell proliferation and function (73) as well as impaired Th2 differentiation (74), Par-4–deficient mice had increased B-cell proliferation and their T cells overproduced the Th2 cytokine IL-4 in vitro and ex vivo (116).

Collectively these observations indicate that Par-4 is a physiologically relevant, naturally occurring negative regulator of inflammation through its ability to negatively affect the aPKC-NF-κB tandem. However, Par-4 was initially identified as a pro-apoptotic molecule in cell cultures (25, 117), and our in vivo mouse work has established that this is also true in vivo, specifically in prostate cancer (118). This is not totally unexpected as NF-κB is a prosurvival transcription factor and it is known that its ablation in vitro and in vivo gives rise to increased apoptosis, although its role in cancer seems to be organ or tissue specific (119). In this context, our data analyzing the tumor phenotype of Par-4-deficient mice adds another layer to the regulatory pathways controlling carcinogenesis through NF-κB and its crosstalk with other relevant signaling pathways. Interestingly, we found that upon aging, at least 80% of Par-4 KO females developed endometrial hyperplasia and at least 36% developed endometrial adenocarcinomas after 1 year of age (120). Also, Par-4 KO males had a high incidence of prostate hyperplasia and intraepithelial neoplasias (121), strongly suggesting that Par-4 is in fact a tumor suppressor. This was confirmed in human cancers in which Par-4 was found to be downregulated in 40% of human endometrial carcinomas (120), and it was lost in a 60% of human prostate carcinomas (118) and in 47% of non-small cell lung carcinomas (122). In this case, there is a clear correlation between the loss of Par-4 and tumor type, since 41% of the adenocarcinomas were negative for Par-4 expression whereas only 6% of squamous cell carcinomas showed negative staining for Par-4. Also, when the adenocarcinomas were stratified by grade, it was clear that 74% of grade III tumors had lost Par-4 expression, whereas 59% of grade I-II tumors were negative for Par-4 (122). Therefore, the role of Par-4 as a potential tumor suppressor linked to its ability to modulate cell survival through the aPKC-NF-κB cassette is likely relevant in human cancers. Recent in vivo results from our own laboratory in physiologically relevant mouse models confirmed this hypothesis and revealed the existence of unexpected signaling crosstalk orchestrated by the Par-4-aPKC module important for cancer and the associated inflammatory response. This evidence was obtained in two mouse cancer models relevant to the types of human tumors in which we have found inhibition of Par-4 expression. One is the PTEN-deficiency-driven prostate cancer model. In this model we found that Par-4 deficiency resulted in a phenotype very similar to that of PTEN-heterozygous mice, which developed only benign prostate lesions (118). However, the concomitant homozygous inactivation of Par-4 in a heterozygous PTEN background led to invasive prostate carcinoma in mice (118). These are very important observations because they establish a physiologically relevant cooperation between Par-4 and PTEN in the development of prostate cancer in mice and likely in humans.

Consistent with the data from human lung cancers, Par-4 not only inhibits PTEN-deficiency-driven carcinogenesis but also keeps the tumorigenic process at bay even when it is activated by an oncogenic signal. In this regard, we have also shown that the loss of Par-4 clearly enhanced lung carcinogenesis in a highly relevant mouse model of this disease (122). Sine Par-4 is reduced primarily in adenocarcinomas and because this type of lung cancer is the one that best correlates with the expression of oncogenic Ras (123), we hypothesized that loss of Par-4 would promote tumorigenesis triggered by this oncogene and possibly others. This hypothesis was supported by crossing the Par-4 KO mice with a model of pulmonary adenocarcinoma in which oncogenic Ras was introduced by a knockin strategy and was inducibly expressed in an endogenous manner (124). Upon Ras expression, these mice develop lung adenomas and adenocarcinomas, with the likely target cell being the type II pneumocyte (124, 125). This is a physiologically relevant model for human cancer, as it has been reported that, in addition to Clara cells, type II pneumocytes are the most likely precursors of human lung adenocarcinomas (125–127). Interestingly, mice lacking Par-4 showed increased lung adenocarcinomas in this model, which was associated with enhanced cell proliferation in vivo as determined by increased Ki67 staining compared with WT lungs (128).

These findings demonstrate that Par-4 loss results in benign neoplasias and enhanced tumorigenesis in at least two mouse models driven by either the loss of a tumor suppressor or the induction of an oncogene. Also, we have shown that Par-4 is lost in human tumors. As Par-4 is a negative regulator of NF-κB through aPKC, the critical question is whether these novel effects account for enhanced NF-κB production in Par-4–deficient tumors. As the loss of Par-4 leads to synergistic cooperation with PTEN heterozygosity for the induction of prostate carcinomas, it could be predicted that they would also cooperate to activate NF-κB if this were the causative mechanism of the enhanced tumorigenicity of the double mutant prostates. Our laboratory demonstrated that this was indeed the case, as we found that whereas the single insufficiency of Par-4 or PTEN was enough to modestly activate NF-κB, this activation was synergistically enhanced in the double-mutant prostates, even at the preneoplastic stage, indicating that enhanced NF-κB activation was not a consequence but likely the cause of the cooperation between the two tumor suppressors (118). This concept was further supported by the analysis of a large array of human prostate tumor samples, reinforcing the physiological relevance of these findings (118). This cooperation was cell autonomous, as demonstrated in several mouse and human cell culture model systems in which it was also shown that the genetic or pharmacological inactivation of NF-κB dramatically reduced Par-4/PTEN deficiency-driven tumorigenicity (118). Mechanistically, PTEN is a negative regulator of Akt activation, and we found its activity to be enhanced in the PTEN mutant prostates (118). Surprisingly, we also found enhanced Akt activity in the Par-4 KO prostates. Importantly, activation of Akt was additive in the double Par-4/PTEN mutant prostates, not synergistic like that of NF-κB (118). These observations indicate that (i) Akt is a novel downstream target of Par-4 and (ii) Akt activation does not correlate with the synergistic induction of prostate adenocarcinomas. Previous observations also indicate that the transgenic expression of activated Akt in prostate is not sufficient to drive formation of invasive carcinomas (129). It is possible, as proposed by Baldwin’s laboratory, that there was cross-talk between Akt and NF-κB in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer cells (130) and that this would be exacerbated in the context of Par-4 deficiency through the aPKCs. It was found that Par-4 can actually control Akt because this is a substrate of PKCζ (122). That is, PKCζ has been shown to phosphorylate Ser473 and Ser124 in vivo and in vitro, and these phosphorylations are antagonized by Par-4 (122). Ser473 is also targeted by the Torc2 complex, and our experiments using rictor knockdown strategies demonstrated that PKCζ is not the major contributor to phosphorylation at this site but that it is for Ser124 (122, 131). The phosphorylation of this residue, along with that of Thr450, is important in facilitating the phosphorylation of Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and mTorc2, respectively (131, 132). Therefore, the Par-4/PKCζ complex emerges as a critical cassette in the control of Akt and NF-κB in at least two types of neoplasias, prostate and lung. These observations also unveil the complexity of the aPKC’s actions, which are not limited to the activation of NF-κB, but which also include the regulation of Akt the Jak1/Stat6 pathway.

Perspectives: conclusions and outstanding questions

It is clear from this review that the atypical PKCs regulate different mechanisms depending on the cell system and organ, likely due in part to the fact that they are relatively promiscuous kinases whose activities must be regulated by the interaction with adapters. Specifically, PKCζ has both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, which complicates the interpretation of the mouse KO phenotypes but, at the same time, underscores the complexity of the inflammatory process. PKCζ is also a tumor suppressor and future studies should elucidate the contributions of its connection to NF-κB and/or Stat6 in carcinogenesis, especially from the point of view of the different cell types that populate the tumor microenvironment. Also, the connection between the aPKCs and p62 in inflammation and cancer should be addressed using genetic in vivo models, as should the link between novel PB1-containing adapters, such as NBR1, in metabolism and cancer.

Acknowledgments

NIH Grants R01CA132847 (J.M.), R01AI072581 (J.M.), R01DK088107 (J.M.), R01CA134530 (M.T.D.-M.), and a Department of Defense Grant DoD-PC080441 (M.T.D.-M.) funded this work. We thank Maryellen Daston for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hanks SK, Hunter T. Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 1995;9:576–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellor H, Parker PJ. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem J. 1998;332:281–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3320281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishizuka Y. The role of protein kinase C in cell surface signal transduction and tumour promotion. Nature. 1984;308:693–698. doi: 10.1038/308693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura S, Yamamura H. Yasutomi Nishizuka: father of protein kinase C. J Biochem. 2010;148:125–130. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kikkawa U, Takai Y, Tanaka Y, Miyake R, Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C as a possible receptor protein of tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11442–11445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leach KL, James ML, Blumberg PM. Characterization of a specific phorbol ester aporeceptor in mouse brain cytosol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4208–4212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castagna M, Takai Y, Kaibuchi K, Sano K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Direct activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7847–7851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sumimoto H, Kamakura S, Ito T. Structure and function of the PB1 domain, a protein interaction module conserved in animals, fungi, amoebas, and plants. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:re6. doi: 10.1126/stke.4012007re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terasawa H, et al. Structure and ligand recognition of the PB1 domain: a novel protein module binding to the PC motif. EMBO J. 2001;20:3947–3956. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn P, Mellor H, Casamassima A, Parker PJ. Rho GTPase control of protein kinase C-related protein kinase activation by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11064–11070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newton AC. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem J. 2003;370:361–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parekh DB, Ziegler W, Parker PJ. Multiple pathways control protein kinase C phosphorylation. EMBOJ. 2000;19:496–503. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pears CJ, Kour G, House C, Kemp BE, Parker PJ. Mutagenesis of the pseudosubstrate site of protein kinase C leads to activation. Eur J Biochem. 1990;194:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Good JA, Ziegler WH, Parekh DB, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Parker PJ. Protein kinase C isotypes controlled by phosphoinositide 3-kinase through the protein kinase PDK1. Science. 1998;281:2042–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facchinetti V, et al. The mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 controls folding and stability of Akt and protein kinase C. EMBO J. 2008;27:1932–1943. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikenoue T, Inoki K, Yang Q, Zhou X, Guan KL. Essential function of TORC2 in PKC and Akt turn motif phosphorylation, maturation and signalling. EMBO J. 2008;27:1919–1931. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balendran A, Biondi RM, Cheung PC, Casamayor A, Deak M, Alessi DR. A 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) docking site is required for the phosphorylation of protein kinase Czeta (PKCzeta) and PKC-related kinase 2 by PDK1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20806–20813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biondi RM, Cheung PC, Casamayor A, Deak M, Currie RA, Alessi DR. Identification of a pocket in the PDK1 kinase domain that interacts with PIF and the C-terminal residues of PKA. EMBO J. 2000;19:979–988. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:281–294. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang QJ, Bhattacharyya D, Garfield S, Nacro K, Marquez VE, Blumberg PM. Differential localization of protein kinase C delta by phorbol esters and related compounds using a fusion protein with green fluorescent protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37233–37239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi H, Brewer KA, Exton JH. Activation of the zeta isozyme of protein kinase C by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limatola C, Schaap D, Moolenaar WH, van Blitterswijk WJ. Phosphatidic acid activation of protein kinase C-zeta overexpressed in COS cells: comparison with other protein kinase C isotypes and other acidic lipids. Biochem J. 1994;304:1001–1008. doi: 10.1042/bj3041001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller G, Ayoub M, Storz P, Rennecke J, Fabbro D, Pfizenmaier K. PKC zeta is a molecular switch in signal transduction of TNF-alpha, bifunctionally regulated by ceramide and arachidonic acid. EMBO J. 1995;14:1961–1969. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozano J, et al. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for kappa B-dependent promoter activation by sphingomyelinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19200–19202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiazMeco MT, et al. The product of par-4, a gene induced during apoptosis, interacts selectively with the atypical isoforms of protein kinase C. Cell. 1996;86:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. The atypical protein kinase Cs - Functional specificity mediated by specific protein adapters. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:399–403. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. The atypical protein kinase Cs. Functional specificity mediated by specific protein adapters. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:399–403. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson MI, Gill DJ, Perisic O, Quinn MT, Williams RL. PB1 domain-mediated heterodimerization in NADPH oxidase and signaling complexes of atypical protein kinase C with Par6 and p62. Mol Cell. 2003;12:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamark T, et al. Interaction codes within the family of mammalian Phox and Bem1p domain-containing proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34568–34581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macara IG. Par proteins: partners in polarization. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R160–R162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohno S. Intercellular junctions and cellular polarity: the PAR-aPKC complex, a conserved core cassette playing fundamental roles in cell polarity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:641–648. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puls A, Schmidt S, Grawe F, Stabel S. Interaction of protein kinase C zeta with ZIP, a novel protein kinase C- binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6191–6196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez P, De Carcer G, Sandoval IV, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. Localization of atypical protein kinase C isoforms into lysosome- targeted endosomes through interaction with p62. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3069–3080. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. p62 at the crossroads of autophagy, apoptosis, and cancer. Cell. 2009;137:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avila A, Silverman N, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. The Drosophila atypical protein kinase C-ref(2)p complex constitutes a conserved module for signaling in the toll pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8787–8795. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8787-8795.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian Y, et al. C. elegans screen identifies autophagy genes specific to multicellular organisms. Cell. 2010;141:1042–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT, Wooten MW. Of the atypical PKCs, Par-4 and p62: recent understandings of the biology and pathology of a PB1-dominated complex. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1426–1437. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominguez I, Sanz L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Diaz-Meco MT, Virelizier JL, Moscat J. Inhibition of protein kinase C zeta subspecies blocks the activation of an NF-kappa B-like activity in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1290–1295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berra E, et al. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for mitogenic signal transduction. Cell. 1993;74:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz-Meco MT, et al. A dominant negative protein kinase C zeta subspecies blocks NF-kappa B activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4770–4775. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Folgueira L, et al. Protein kinase C-zeta mediates NF-kappa B activation in human immunodeficiency virus-infected monocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:223–231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.223-231.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sontag E, Sontag JM, Garcia A. Protein phosphatase 2A is a critical regulator of protein kinase C zeta signaling targeted by SV40 small t to promote cell growth and NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 1997;16:5662–5671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anrather J, Csizmadia V, Soares MP, Winkler H. Regulation of NF-kappaB RelA phosphorylation and transcriptional activity by p21(ras) and protein kinase Czeta in primary endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13594–13603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin AG, San-Antonio B, Fresno M. Regulation of nuclear factor kappa B transactivation. Implication of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase C zeta in c-Rel activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15840–15849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaVallie ER, et al. Protein kinase Czeta is up-regulated in osteoarthritic cartilage and is required for activation of NF-kappaB by tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24124–24137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz-Meco MT, et al. zeta PKC induces phosphorylation and inactivation of I kappa B-alpha in vitro. EMBO J. 1994;13:2842–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lallena MJ, Diaz-Meco MT, Bren G, Pay CV, Moscat J. Activation of IkappaB Kinase beta by Protein Kinase C Isoforms. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2180–2188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leitges M, et al. Immunodeficiency in protein kinase cbeta-deficient mice. Science. 1996;273:788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Essential role of RelA Ser311 phosphorylation by zetaPKC in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 2003;22:3910–3918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen LF, Greene WC. Shaping the nuclear action of NF-kappaB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkins ND. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:6717–6730. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong H, Voll RE, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol Cell. 1998;1:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Essential role of RelA Ser311 phosphorylation by zeta PKC in NF-kappa B transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 2003;22:3910–3918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vermeulen L, De Wilde G, Damme PV, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. Transcriptional activation of the NF-κB p65 subunit by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) EMBO J. 2003;22:1313–1324. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong H, May MJ, Jimi E, Ghosh S. The phosphorylation status of nuclear NF-kappa B determines its association with CBP/p300 or HDAC-1. Mol Cell. 2002;9:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhong H, SuYang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. The transcriptional activity of NF-kappaB is regulated by the IkappaB- associated PKAc subunit through a cyclic AMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 1997;89:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leitges M, et al. Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappaB pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;8:771–780. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang XD, Tajkhorshid E, Chen LF. Functional interplay between acetylation and methylation of the RelA subunit of NF-kappaB. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2170–2180. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01343-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gringhuis SI, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, van Het Hof B, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. C-type lectin DC-SIGN modulates Toll-like receptor signaling via Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. Immunity. 2007;26:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang XD, Huang B, Li M, Lamb A, Kelleher NL, Chen LF. Negative regulation of NF-kappaB action by Set9-mediated lysine methylation of the RelA subunit. EMBO J. 2009;28:1055–1066. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ea CK, Baltimore D. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity through lysine monomethylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18972–18977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen LF, Greene WC. Assessing acetylation of NF-kappaB. Methods. 2005;36:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levy D, Kuo AJ, Chang Y, Schaefer U, Kitson C, Cheung P. SETD6 lysine methylation of RelA couples GLP activity at chromatin to tonic repression of NF-kappaB signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:29–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tachibana M, et al. Histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP form heteromeric complexes and are both crucial for methylation of euchromatin at H3-K9. Genes Dev. 2005;19:815–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tachibana M, Matsumura Y, Fukuda M, Kimura H, Shinkai Y. G9a/GLP complexes independently mediate H3K9 and DNA methylation to silence transcription. EMBO J. 2008;27:2681–2690. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang Y, et al. Structural basis of SETD6-mediated regulation of the NF-kB network via methyl-lysine signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6380–6389. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoffmann JA. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;426:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nature02021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ganesan S, Aggarwal K, Paquette N, Silverman N. NF-kappaB/Rel proteins and the humoral immune responses of Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;349:25–60. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hetru C, Hoffmann JA. NF-kappaB in the immune response of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harbor Persp Biol. 2009;1:a000232. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goto A, Blandin S, Royet J, Reichhart JM, Levashina EA. Silencing of Toll pathway components by direct injection of double-stranded RNA into Drosophila adult flies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6619–6623. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leitges M, et al. Targeted disruption of the zeta PKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappa B pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;8:771–780. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martin P, et al. Role of zeta PKC in B-cell signaling and function. EMBO J. 2002;21:4049–4057. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martin P, et al. Control of T helper 2 cell function and allergic airway inflammation by PKCζ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9866–9871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501202102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ho IC, Glimcher LH. Transcription: tantalizing times for T cells. Cell. 2002;109 (Suppl):S109–S120. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duran A, et al. Crosstalk between PKCzeta and the IL4/Stat6 pathway during T-cell-mediated hepatitis. EMBO J. 2004;23:4595–4605. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tiegs G, Hentschel J, Wendel A. A T cell-dependent experimental liver injury in mice inducible by concanavalin A. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:196–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI115836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maeda S, Chang L, Li ZW, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M. IKKbeta is required for prevention of apoptosis mediated by cell-bound but not by circulating TNFalpha. Immunity. 2003;19:725–737. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M. IKKbeta couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:977–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jaruga B, Hong F, Sun R, Radaeva S, Gao B. Crucial role of IL-4/STAT6 in T cell-mediated hepatitis: up-regulating eotaxins and IL-5 and recruiting leukocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171:3233–3244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109 (Suppl):S81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Diaz-Meco MT, et al. The product of par-4, a gene induced during apoptosis, interacts selectively with the atypical isoforms of protein kinase C. Cell. 1996;86:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garcia-Cao I, Lafuente M, Criado L, Diaz-Meco M, Serrano M, Moscat J. Genetic inactivation of Par4 results in hyperactivation of NF-κB and impairment of JNK and p38. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:307–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lafuente MJ, Martin P, Garcia-Cao I, Diaz-Meco MT, Serrano M, Moscat J. Regulation of mature T lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation by Par-4. EMBO J. 2003;22:4689–4698. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martin P, et al. Role of zeta PKC in B-cell signaling and function. EMBO J. 2002;21:4049–4057. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Klinger M, Kim JK, Chmura SA, Barczak A, Erle DJ, Killeen N. Thymic OX40 expression discriminates cells undergoing strong responses to selection ligands. J Immunol. 2009;182:4581–4589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang JQ, Leitges M, Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Loss of PKC lambda/iota impairs Th2 establishment and allergic airway inflammation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1099–1104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805907106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Suzuki A, Ohno S. The PAR-aPKC system: lessons in polarity. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:979–987. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Humbert PO, Dow LE, Russell SM. The Scribble and Par complexes in polarity and migration: friends or foes? Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee SJ, et al. PKCzeta-regulated inflammation in the nonhematopoietic compartment is critical for obesity-induced glucose intolerance. Cell Metab. 2010;12:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Qatanani M, Lazar MA. Mechanisms of obesity-associated insulin resistance: many choices on the menu. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1443–1455. doi: 10.1101/gad.1550907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sabio G, et al. A stress signaling pathway in adipose tissue regulates hepatic insulin resistance. Science. 2008;322:1539–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1160794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schenk S, Saberi M, Olefsky JM. Insulin sensitivity: modulation by nutrients and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2992–3002. doi: 10.1172/JCI34260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kang K, et al. Adipocyte-derived Th2 cytokines and myeloid PPARdelta regulate macrophage polarization and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2008;7:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Odegaard JI, et al. Alternative M2 activation of Kupffer cells by PPARdelta ameliorates obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2008;7:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]