Abstract

The purpose of this study was to advance our understanding of nonmedical use of prescription medications by identifying distinguishing characteristics of two subtypes of adolescent nonmedical users of prescription opioids described by Boyd and McCabe1. A web-based, self-administered survey was completed by 2,597 7th – 12th grade students. Sensation seeking nonmedical users were best characterized by rule breaking and aggressive behaviors and possible substance dependence. Medical users and nonmedical self treating users were best characterized by somatic complaints, anxiety/depressive symptoms, and history of sexual victimization.

Keywords: prescription opioids, motives, adolescents, substance abuse, problem behaviors

Introduction

The nonmedical use of prescription opioids among adolescents has been a growing health concern over the last decade.2,3,4 National estimates indicate that in 2010 approximately 6.2% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 and 9.5% of 12th graders have engaged in the nonmedical use of controlled pain medications.3,5 Furthermore, opioid analgesics are the class of controlled medications most likely to be used, misused, and/or abused by adolescents and young adults.3,5,6

Background

In 2008, Boyd and McCabe, researchers with a long-standing interest in the nonmedical use of controlled medications, posed a descriptive model pertaining to this form of substance misuse and abuse. They posited that there are several subtypes of nonmedical users. Their model, based on previous studies with adolescent and young adult populations,7,8,9,10 stipulates at least two different groups that engage in nonmedical use of controlled medications: those adolescents who misuse their own controlled medications, or alternatively, those who misuse someone else's medicine. However, Boyd and McCabe also contend that these two groups can be further divided by their motivations to engage in nonmedical use - 1) those using to self-treat a perceived medical symptom versus 2) those engaging in sensation-seeking or recreational drug use.

There are few empirical studies that test Boyd and McCabe's model on subtypes of nonmedical users. The few studies that have examined subtypes have only identified distinguishing characteristics and behaviors for the sensation-seekers.7,8,9,11,12,13 These studies indicate that the likelihood of using opioids nonmedically is increased if youths have high rates of illicit drug use,10,14,15 favorable attitudes towards drug use,4 high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms,15 or a history of delinquency.10,15 However, research on the correlates of nonmedical use suggests that the presence of a self-treating subtype. For example, nonmedical use of opioids has been associated with being female,4,16 utilizing mental health treatment,4 having a history of being sexual victimized by peers,17 or witnessing violence.15 Thus, while researchers have been better able to clarify the distinguishing characteristics of nonmedical sensation-seekers, additional research is needed to differentiate self-treaters from medical users and non-users.

Hypothesis development

To identify characteristics and behaviors that would best distinguish self-treaters from sensation-seekers, theoretical frameworks used to understand adolescent substance use were drawn upon for the current study. Problem behavior theory (PBT)18,19 has been used to understand high rates of illicit drug use, delinquency, and early sexual activity among adolescent nonmedical users of controlled medications.7,12,13 According to this line of thinking, nonmedical use of prescription medications is one of a variety of adolescent risk behaviors that co-occur because of an underlying problem behavior syndrome. Problem Behavior Theory might best be used to understand sensation-seekers and their behaviors. A self-medication model has previously been used to explain nonmedical prescription use of opioids,15,17 and may be useful in understanding self-treaters and their behaviors. Based on the self-medication model, prescription opioids are thought to be used to self-treat physical pain symptoms and psychological symptoms following traumatic or stressful events. Thus, nonmedical use of prescription opioids among adolescents, particularly female adolescents, may be related to their conscious or unconscious attempt to address physical, psychological, or psychosomatic symptoms.

Current study

The purpose of the current study was to expand the range of characteristics and behaviors examined with the intent of differentiating self-treaters and sensation-seekers from medical users and nonusers. Using discriminant function analysis (DFA), the goal was to identify those characteristics that were best able to differentiate the self-treaters from sensation-seekers, particularly in terms of emotional and behavioral problems, physical health symptoms, health risk behaviors, and victimization by peers.

Two hypotheses guided the study. In line with problem behavior theory, we first hypothesized that nonmedical users of prescription opioids who use for reasons other than relieving pain (i.e., sensation-seekers) would be best described by characteristics previously associated with this syndrome, including rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior, alcohol and illicit drug use, and early sexual behaviors. Based on the self-treatment model, the second hypothesis was that nonmedical users who use to relieve physical pain (i.e., self-treaters) would be best described by characteristics previously associated with the use of substances as a means of treating physical and psychological symptoms. These variables include physical pain, depression, somatization, and victimization by peers. These two subtypes of nonmedical users (sensation-seekers and self-medicators) were contrasted with each other as well as with medical users of prescription opioids and adolescents who had not used prescription opioids.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a web-based, self-administered survey of middle and high school students enrolled in two school districts in Southeastern Michigan from December 2009 to April 2010. Approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan, a Certificate of Confidentiality, parental consent, and student assent were obtained prior to any data collection. The web-based survey was administered in the school setting during a class period or lunch period in an area that provided privacy. The survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete and was supervised by the research team. Data from the survey were transmitted to a private research firm using a hosted Internet site running under secure sockets layers (SSL) to ensure safe transmission of data. To maintain confidentiality, students were provided with a unique identification number that they used to enter the survey. Students were not compensated for participation in the survey.

Participants

All students attending the two school districts in 7th - 12th grades were invited to participate; 2,597 students completed the survey representing a 62% response rate based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guideline #2. The sample was evenly distributed by sex (49.6% male and 50.4% female) and grade (17.1% 7th graders, 17.9% 8th graders, 17.6% 9th graders, 15.1% 10th graders, 16.0% 11th graders, and 16.4% 12th graders). Sixty-five percent (65.0%) were White/Caucasian, 29.5% were African-American, 3.7% were Asian, 1.3% were Hispanic, and .5% were American Indian/Alaskan Native. The average age was 14.8 (SD=1.9) years. Comparison of respondents and nonrespondents indicated that nonresponse was significantly associated with race/ethnicity (χ2 = 23.9, df = 3, p < .05): Hispanics had a higher nonresponse rate (62.5%) compared to Whites (49.0%), Blacks (41.1%), and Asians (41.7%). Response status was not associated with sex and age.

Instruments

Prescription Opioid Use Groups

A four-level categorical variable was created using three questions pertaining to opioid use in the past 12 months. This variable construction approach has been employed previously9 and was used for the current study to allow for comparisons to previous research. The first question asked about medical use of prescription opioids: “The following questions are about the use of prescribed medicines. We are not interested in your use of over the counter medicines that can be bought in drug or grocery stores without a prescription, such as aspirin, Sominex®, Benadryl®, Tylenol PM®, cough medicine etc. How many times in the past 12 months has a doctor, dentist, or nurse prescribed the following types of medicine for you?” The respondent was then asked about various classes of drugs, one of which was described as prescribed pain medications (e.g., opioids such as Vicodin®, OxyContin®, Tylenol 3® with codeine, Percocet®, Darvocet®, morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone). The second question asked about nonmedical use of opioids with the following: “Sometimes people use prescription medications that were meant for other people, even when their own Health Professional (e.g., doctor, dentist, nurse) has not prescribed it for them. How many occasions in the past 12 months have you used the following types of medicines, not prescribed to you?” Using the same format as the question about medical use, respondents were asked about a variety of drug classes, one of which was prescription opioid use, and were provided with the same seven response options. If opioids had been used nonmedically, respondents were asked about the reasons why they had used with the following question: “Please provide the reason(s) why you used pain medication not prescribed to you. (Select all that apply). 1) because it relieves pain, 2) because it helps me sleep, 3) because it helps decrease anxiety, 4) because it gives me a high, 5) because it counteracts the effects of other drugs, 6) because it is safer than street drugs, 7) because of experimentation, 8) because I am addicted. 9) other.” Respondents were allowed to report more than one motive. The four-level categorical use variable was created with the following algorithm: 1) adolescents who indicated that they had not used opioids in the past 12 months either medically or nonmedically were assigned to the nonuser group; 2) adolescents who had used at least once in the past 12 months medically, but not nonmedically, were assigned to the medical user group; 3) adolescents who had nonmedically used at least once in the past 12 months to relieve pain only were assigned to the self-treater group; and 4) adolescents who had used at least once nonmedically in the past 12 months for reasons other than to relieve pain were assigned to the sensation-seeker group.

Emotional and Behavioral Problems

The Youth Self Report (YSR) version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was included in the self-administered survey and was used to measure anxious/depressed symptoms, withdrawn/depressed symptoms, somatic complaints, rule-breaking behaviors, and aggressive behaviors. The CBCL is a commonly used instrument for measuring various types of behavioral and emotional problems, and the acceptable psychometric properties of the YSR version as well as other versions have been well documented.20

Physical Pain

Pain symptoms were measured with a six item index previously used in the National Youth Survey (NYS).21 The index asks about the prevalence of physical health symptoms in the past 30 days (e.g., headaches, sore throat, trouble with sinus congestion, chest colds) with response options of none, 1 day, 2 days, 3–5 days, 6–9 days, 10 to 19 days, or 20+ days. A sum score was created with the six items.

Victimization

Respondents were asked about their own experiences of being victimized by other students in terms of social, physical, and sexual aggression.22,23 The social scale consisted of three items (e.g., “how often in the previous month have students told stories about you that were untrue?”), and the physical scale consisted of three items (e.g., “how often in the previous month have other students hit, pushed, or kicked you on purpose?”). Sexual victimization by peers was measured with a modified version of the Sexual Experiences Survey that has been described in depth previously.23 Respondents were to report acts that occurred with peers of the opposite sex and who were approximately the same age. The scale consisted of six items that ranged from sexual harassment (e.g., “Made sexual jokes or teasing comments about you even though you did not want it”), to unwanted sexual touching (e.g., “Kissed, hugged, or sexually touched you even though you did not want it?”), to rape (e.g., “Made you have sexual intercourse even though you did not want it”). The inter-item reliabilities for the social, physical, and sexual victimization scales were .74, .74, and .83 respectively.

Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use

A measure of binge drinking, adapted from the College Alcohol Study, was included to measure the frequency of binge drinking (i.e., at least four drinks per occasion for females and at least five drinks per occasion for males) that occurred in the past two weeks.24 Marijuana and other illicit drug use were measured with items from the Monitoring the Future study.3 Marijuana use was assessed with a single item that asked about use in the past 12 months. A measure of lifetime use of illicit drugs (other than marijuana) was created by asking respondents about the use of 10 different illicit drugs, including cocaine, LSD, other psychedelics, methamphetamines (crystal), heroin, inhalants, ecstasy, GHB, rohypnol, and anabolic steroids. A count of the number of illicit drugs ever used was created.

Risk for Substance Dependence

The CRAFFT instrument was used to measure risk for alcohol and illicit drug dependence.25 The CRAFFT instrument is a six item self- report instrument with items such as “Do you ever use alcohol/drugs while you are by yourself, alone?” The scale was created by summing the items and the inter-item reliability for this instrument was .77.

Early Sexual Activity

Information regarding the respondents' sexual activity was measured with a seven item Guttman-type scale that asked whether the respondent had ever engaged in various sexual activities, ranging from kissing to various stages of petting and sexual intercourse.26 Response options included: never, once, 2–3 times, 4 or more times. A sum score was created and the inter-item reliability for this scale was .95.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 18.0 was used to perform all data analysis. Frequencies and cross tabulations were conducted prior to hypothesis testing to describe the opioid use groups in terms of demographic characteristics. ANOVA tests were conducted to examine differences among the four user groups on the predictor variables. Discriminant function analysis (DFA) was used to test the hypotheses, as this statistical test is most suitable for identifying the optimal combination of the predictor variables to differentiate predetermined groups (such as the opioid user types). Finally, the relationship between the significant discriminant functions and demographic characteristics were examined with ANOVA tests and bivariate correlations.

Results

Approximately 14% (n=373) of the sample reported medical use of prescription opioids in the past 12 months, while 5% (n=148) of the sample reported nonmedical use of prescription opioids in the past 12 months. The most common reason for nonmedical use was “to relieve pain” (n=91, 62.8%), followed by “to get high” (n=23, 15.9%) and “to experiment” (n=16, 11.0%). In terms of the opioid user classification, 82.5% (n=2158) were identified as nonusers, 12.3% (n=323) were identified as medical users, 2.7% (n=70) were identified as nonmedical self-treaters, and 2.5% (n=66) were identified as nonmedical sensation-seekers. Respondents reporting both self-treatment and sensation-seeking motivations (n=21) were classified as sensation-seekers.

Gender was significantly associated with the opioid use group (χ2 = 51.5, DF=3, p<.001): female respondents represented 65.9% of the medical users, 70.0% of the self-treaters, and 62.1% of the sensation-seekers, but only 47.7% of the nonusers. Grade level also was associated with the opioid user group (F = 10.2, DF = 3, p<.001). Post-hoc Bonferroni tests indicated that the sensation-seeking group (M = 10.1) and medical user group (M=9.84) were significantly higher in grade level than the nonuser group (M=9.37) at the p<.05 level; however, the self-treater group was not significantly different than the other three groups. Race/ethnic background was not associated with the opioid user group.

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations of the predictor variables as a function of the four-level categorical opioid use variable. In general, all prescription opioid user groups scored higher than nonusers on many of the predictor variables. While not presented in Table 1, 70.7% (n=29) of the sensation-seekers reported a positive screen on the CRAFFT (positive for 2 or more items), in contrast to 17.7% (n=55) of medical users, 20.7% (n=19) of self-treaters, and 10.0% (n=211) of nonusers of pain medication (χ2 = 153.5, DF=3, p<.001). Moreover, sensation-seeking nonmedical users were significantly higher than the medical users and self-treaters on many of the predictor variables.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of predictor variables as a function of opioid user groups.

| Nonusers (n=2158) | Medical Users (n=323) | Nonmedical Self-treaters (n=70) | Nonmedical Sensation-Seekers (n=66) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Anxious/Depressed (YSR) | 3.98abc | 4.08 | 5.92a | 5.53 | 5.71b | 4.41 | 7.50c | 5.65 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed (YSR) | 3.12abc | 2.79 | 3.98a | 3.28 | 4.14b | 2.76 | 5.22c | 3.13 |

| Somatic Complaints (YSR) | 2.82abc | 2.74 | 4.69a | 4.01 | 4.56b | 3.36 | 5.17c | 4.10 |

| Rule Breaking (YSR) | 3.63abc | 3.35 | 4.85a | 4.15 | 4.91be | 3.85 | 10.25c | 6.52 |

| Aggressive Behavior (YSR) | 5.05abc | 4.27 | 6.26ad | 4.96 | 7.64be | 4.39 | 10.38c | 6.28 |

| Physical Symptoms | 1.92ab | .83 | 2.30ac | 1.31 | 2.09d | .91 | 2.82bcd | 1.31 |

| Binge Drinking | .03ad | .17 | .06b | .25 | .09c | .28 | .43abc | .05 |

| Marijuana Use | .09ad | .29 | .16b | .37 | .14c | .35 | .51abc | .50 |

| Illicit Substance Use* | .03a | .29 | .06b | .23 | .06c | .23 | .31abc | .47 |

| CRAFFT score | .40a | 1.00 | 1.72b | 1.36 | .81ce | 1.22 | 2.45abc | 2.33 |

| Early Sexual Behavior | 2.21ad | 1.08 | 2.55b | 1.07 | 2.39c | 1.11 | 3.10abc | 1.03 |

| Sexual Victimization | 1.25abc | .53 | 1.44a | .68 | 1.45b | .75 | 1.57c | .83 |

| Social Victimization | 1.79acd | .80 | 1.96bc | .80 | 2.06d | .80 | 2.39ab | .93 |

| Physical Victimization | 1.35a | .57 | 1.43 | .69 | 1.47 | .71 | 1.57a | .71 |

Note: Means with the same subscript differ significantly at the p<.05 level. Total number of cases in analyses ranged from 2530 to 2597 due to missing cases on some of the predictor variables.

Illicit substance use excludes marijuana use.

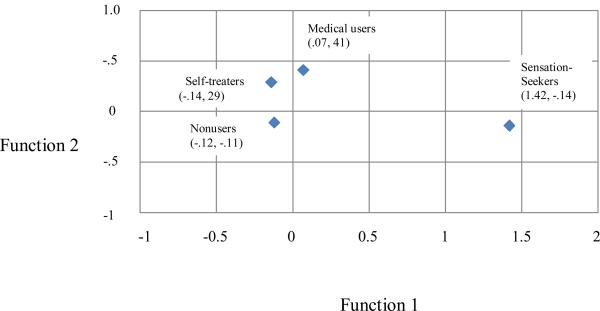

The DFA identified two significant functions (See Table 2), which are discussed below in terms of the two study hypotheses. The group centroids plot from the DFA is presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Correlations between Discriminating Variables and Discriminant Functions (Function Structure Matrix).

| Variable | Function 1a | Function 2b |

|---|---|---|

| Rule Breaking Behavior (YSR) | .80* | −.09 |

| CRAFFT score | .70* | −.05 |

| Illicit Drug Use | .58* | −.14 |

| Aggressive Behavior (YSR) | .54* | .07 |

| Physical Symptoms | .50* | .42 |

| Marijuana Use | .43* | −.15 |

| Binge Drinking | .39* | .03 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed (YSR) | .38* | .30 |

| Social Victimization | .36* | −.06 |

| Physical Victimization | .20* | .06 |

| Somatic Complaints (YSR) | .34 | .78* |

| Anxious/Depressed (YSR) | .42 | .49* |

| Sexual Victimization | .17 | .25* |

| Early Sexual Activity | .23 | −.26 |

Wilks's λ = .83, χ2 = 190.98, DF=42, p<.001.

Wilks's λ = .94, χ2 = 61.69, DF=26, p<.001.

Largest absolute correlation between each variable and any function.

Figure 1.

Group centroids plot from discriminant function analysis.

Hypothesis 1

Sensation-seeking nonmedical users of opioids would best be described by characteristics previously associated with PBT, including rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior, alcohol and illicit drug use, and early sexual behaviors. The first discriminant function best distinguished sensation-seekers. The opioid group with the highest group centroid for the first function was the sensation-seekers (1.42), followed by the medical users (.07), the nonusers (−.12), and the self-medicating nonmedical users (−.14). Predictor variables with the highest association with the first function were rule-breaking behaviors, high risk for substance dependence (i.e., CRAFFT score), number of illicit drugs used in lifetime, and aggressive behaviors. ANOVA tests indicated that race/ethnicity was significantly associated with the first function, F (2, 2634) = 6.81, p<.001, with White respondents scoring significantly higher on average than African-American respondents (−.22 versus −.33 respectively). Moreover, the interaction term for race/ethnicity by grade was significantly associated with the first function, F (10, 2634) = 3.01, p<.001. For White respondents, the first function increased with grade (.20, p<.001), but the association between grade and the first function was not significant for the other race/ethnic groups.

Hypothesis 2

Self-treaters would be best described by characteristics previously associated with the use of substances as a means of treating physical and psychological symptoms, including self-reported physical pain symptoms, depression, somatization, and sexual victimization by peers. The opioid group with the highest group centroid for the second function were medical users (.41) and the self-treaters (.29), while the sensation-seekers (−.14) and nonusers (−.11) were lower on this function. The predictor variables that were highly associated with the second function were somatic complaints, anxious/depressed symptoms, and sexual victimization. Female respondents were significantly higher on the second function than male respondents (females = .34, males = −.22), F (1, 2597) = 292.72, p<.001. Grade was also positively associated with the second function, F (1, 2597) = 74.17, p<.001. Moreover, the interaction term of gender by grade was significant F (1, 2597) = 8.05, p<.01. There was a significant negative association between grade and the second function for male respondents (r= −.24, p<.001), but the association between these variables was not significant for the female respondents. Thus, the significant interaction term indicates that the discriminant function was more characteristic of younger male adolescents than older male adolescents, but was equally characteristic of younger and older female adolescents.

Discussion

The purpose of this study on the nonmedical use of controlled pain (opioid) medications was to differentiate between the individual characteristics associated with adolescents who use opioids to self-treat in contrast to adolescents who use for sensation-seeking reasons. Discriminant function analysis was conducted to distinguish among four subtypes of adolescent prescription opioid users: nonusers, medical users only, nonmedical self-treaters, and nonmedical sensation-seekers. We found two significant discriminant functions that differentiated these groups in a manner that coincides with Boyd and McCabe's theoretical model regarding subtypes.

While representing almost half of all nonmedical prescription opioid users in this study (66 of 136), the sensation-seeking group demonstrated significant psychosocial disturbances that were notable in terms of their severity and breadth. The most distinguishing features of this group were their propensity towards rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior, risk for substance dependence and use of illicit drugs. These findings are in line with previous research9,11,12,13 indicating that sensation-seekers were significantly more likely than self-treaters to report higher levels of substance use and other forms of adolescent problem behaviors. As all of the variables on this function involved the inability to self-regulate (i.e., law breaking behavior, aggressiveness, and risk for substance dependence) suggests that behavioral disinhibition may play a critical role in this group's opioid use. Thus, it may be that the Behavioral Disinhibition Model (BDI),27,28 a model with greater specificity on the nature and origin of (a subset of) problem behaviors than PBT, would be particularly useful in understanding this subtype's opioid use. The BDM proposes that there is a spectrum of externalizing disorders (e.g., conduct disorder, early onset substance use disorders, impulsivity, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) that tend to co-occur and reflect an inability to control socially undesirable behavior. The BDI model is similar to PBT in that both explain adolescent behavior that goes against social norms. However, the BDI model focuses on a specific cluster of externalizing behaviors and more extreme forms of pathology, whereas PBT focuses on a wider scope of adolescent problem behaviors that can range from mild to severe disturbance. Using the BDI model to understand this subtype's opioid use would allow for more targeted prevention and treatment efforts. For example, the BDI model suggests that adolescents with this subtype would have an early onset of opioid misuse (early adolescence) and a rapid progression toward opioid abuse over the course of adolescence. Moreover, the BDI model indicates that risk factors for opioid misuse and abuse among this subtype could be identified during childhood, and include other types of behavioral disinhbition (e.g, ADHD, rule breaking behaviors).

Unique to this study are the findings pertaining to the nonmedical users of prescription opioids who report that they use to relieve physical pain. Self-treaters were best described with a second discriminant function that included somatic symptoms, anxious/depressed symptoms, and a history of sexual victimization by peers. These findings coincide with previous research reporting an association between traumatic experiences and nonmedical opioid use.15,17 Interestingly, medical users of prescription opioids and nonmedical users who use to relieve pain were both equally high on this second factor. These findings indicate that adolescents' use of prescription opioids to relieve physical pain, regardless of how they obtained the medication, was associated with internalizing symptoms and history of victimization. Our study is unable to speak to the nature of the relationship between adolescents' prescription opioid use and these internalizing symptoms, but it does have direct clinical implications. Previous research has indicated that pain symptoms are associated with depression among adolescents,29 suggesting that prescription opioid use and depression may share pain symptoms as a common cause. Alternatively, it could be that somatic symptoms and depression emerge as a result of sexual victimization, and the use of opioids – whether obtained through a prescription or not -- provides a means of treating these symptoms. Regardless, health professionals should inquire about depressive symptoms and victimization experiences when adolescents present themselves with physical pain symptoms and are seeking medications, as we found that medical users of opioids were just as likely as self-medicating nonmedical users to score high on this second discriminant function.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study that should be noted. First, this study relied on self-report and the surveys were completed in school, so findings may underestimate characteristics prevalent among youth who are commonly absent from school. Moreover, our study was conducted in two school districts within the Midwest; a nationally representative study is necessary to determine the generalizability of these findings. Finally, we focused our research on prescription opioids; it is unclear to what extent our findings are applicable to other prescription drug classes. Regardless, this study provides important information on the distinguishing characteristics of two subtypes of nonmedical opioid users.

Conclusions and implications

There has been considerable concern over adolescents' nonmedical use of prescription opioids, in particular because of its dramatic increase since the mid-1990s,3,4 and because it is highly correlated with excessive substance use, the risk of substance use disorders, and other adolescent problem behaviors.4,7,11,12 Findings from this study demonstrate that it is critical for the field to identify adolescents' motivations to nonmedically use prescription opioids when assessing the prevalence and nature of the problem. While this point has been made previously,8,11,12,30 the current study demonstrates that failure to do so results in the blending of two distinct profiles of nonmedical users, and a misunderstanding of both. Our study indicated that only half of adolescent nonmedical prescription opioid users have more extreme forms of behavioral problems. While the remaining half also showed signs of behavioral problems, they were less severe and of a different nature; specifically, these nonmedical users reported somatic and anxious/depressed symptoms and a history of sexual victimization by peers. Moreover, these two distinct profiles of nonmedical users call for distinct forms of intervention; while sensation-seekers would benefit from external regulation of behavior (e.g., firm limit setting) to compensate for the lack of self- regulation, self-treaters would benefit from intervention strategies that focused on identifying the cause of their physical and psychological symptoms that contribute to their opioid use, and may benefit from an evaluation for pain management. These more targeted approaches to understanding and preventing nonmedical prescription opioid use among adolescents are likely to yield more fruitful results than strategies that fail to recognize the heterogeneity among nonmedical prescription opioid users.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health: R01DA024678 (PI: C.J. Boyd) and R01DA031160 (S.E. McCabe).

References

- 1.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE. Coming to terms with the nonmedical use of prescription medications. Sub Abuse Treat Prevent Pol. 2008;3:22. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-22. Available at: http://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/3/1/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(Suppl.):S4–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Secondary school students. Vol. I. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung HE, Richter L, Vaughan R, Johnson P, et al. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among teenagers in the United States: Trends and correlates. J Adol Hlth. 2005;37:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2011. (NSDUH Series H-41). HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Caiola E, Joynt M, Halterman JS. Prescribing of controlled medications to adolescents and young adults in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1108–1116. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd CJ, Young A, Grey M, McCabe SE. Adolescents' nonmedical use of prescription medications and other problem behaviors. J Adol. Health. 2009;45:539–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Adolescents' motivations to abuse prescription medications. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2472–2480. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Teter CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription pain medication by youth in a Detroit-area public school district. Drug Alc Depend. 2006;81:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Illicit use of opioid analgesics by high school seniors. J Sub Abuse & Treat. 2005;28:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Motives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Addict Behav. 2007;32:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA, Teter CJ. Motives for nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States: self-treatment and beyond. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:739–744. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Subtypes of nonmedical prescription drug misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inciardi JA. Prevelance of narcotic analgesic abuse among students, individual or polydrug abuse? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:498–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.5.498-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCauley JL, Danielson CK, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero KJ, et al. The role of traumatic event history in non-medical use of prescription drugs among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. J Child Psych Psychiatry. 2010;51:84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Patkar AA. Non-prescribed use of pain relievers among adolescents in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young AM, Grey M, Boyd CJ, McCabe SE. Adolescent sexual assault and the medical and nonmedical use of prescription medication. J Addict. Nurs. 2010;21:1–7. doi: 10.3109/10884601003628138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan JE, Brooke SG, Molina BSG. Children's introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 12:374–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jessor R. A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Develop Rev. 1992;12:374–390. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achenbach TM. Integrative Guide to the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Univ Vermont, Dept. of Psych; Burlington, VT.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott D. National Youth Survey. ICPSR06542-v3. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 1987. [distributor], 2009-04-01. doi:10.3886/ICPSR06542.v3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein S, Young A, Boyd C. Relational aggression at school: Associations with school safety and social climate. J Youth and Adol. 2008;37:641–654. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young A, Grey M, Abbey A, Boyd C. Alcohol-related sexual assault among adolescents: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Correlates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:39–48. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, et al. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. Am J Public Hlth. 1995;85:982–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, et al. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Udry JR, Bearman PS. New methods for new research on adolescent sexual behavior. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early- onset addition: Common and specific influences. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abn Psych. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers SW, Gilman DK, Hershey AD. Headache and psychological functioning in children and adolescents. Headache. 2006;46:1404–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zacny JP, Lichtor SA. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids: Motive and ubiquity issues. J Pain. 2008;9:473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]