Abstract

Signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family (SLAMF) receptors and the specific adapter SLAM-associated protein (SAP) modulate the development of innate-like lymphocytes. Here, we show that the thymus of Ly9-deficient mice contains an expanded population of CD8 single-positive cells with the characteristic phenotype of innate memory-like CD8+ T-cells. Moreover, the proportion of these innate CD8+ T-cells increased dramatically after infection with mouse cytomegalovirus. Gene expression profiling of Ly9-deficient mice thymi showed a significant up-regulation of IL-4 and PLZF. Analyses of Ly9−/−IL4ra−/− double-deficient mice revealed that IL-4 was needed to generate the thymic innate CD8+ T-cell subset. Furthermore, increased numbers of iNKT cells were detected in Ly9-deficient thymi. In wild-type mice IL-4 levels induced by αGalCer injection could be inhibited by a monoclonal antibody against Ly9. Thus, Ly9 plays a unique role as an inhibitory cell-surface receptor regulating the size of the thymic innate CD8+ T-cell pool and the development of iNKT cells.

Introduction

Innate-like T cells are derived from double-positive (DP) thymocytes, and are selected by non-classical MHC class I molecules. These cells have several characteristics that distinguish them from conventional T cells including a highly restricted TCR repertoire and the rapid generation of effector functions after TCR stimulation without previous exposure to antigen. CD1d-resticted invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, MHC Ib restricted CD8 T cells (H2-M3 restricted) and MHC Ia-restricted innate-like CD8+ T cells are among these T cell types with innate features. The latter population represents a subset of thymic single-positive (SP) CD8 cells characterized by the constitutive expression of high levels of activation markers, which are indicative of a memory-like phenotype (1). Disruption of either the IL-4 or the Cd1d genes in BALB/c mice leads to a reduction in thymic CD8 SP T cells, demonstrating that the cytokine IL-4 secreted by iNKT cells is needed for their development (2, 3). Consistently, recent studies have shown that IL-4 produced by promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF)+ iNKT cells drives CD8+ T cells to acquire an innate-like phenotype (reviewed in 4).

The homotypic interaction between the SLAM receptors (SLAMF1 and SLAMF6), expressed on cortical DP thymocytes and iNKT cell precursors, and the downstream signaling SAP adaptor are essential to the positive selection required for iNKT cell development (5–7). Recently, it has been demonstrated that the innate CD8+ thymocytes driven by iNKT cells need SAP in order to properly develop (8). However, nothing is known about the specific contribution of other SLAM family members to the development of innate-like T lymphocytes.

Ly9 (SLAMF3, CD229) is a homophilic cell surface receptor present on all thymocytes and highly expressed on innate-like lymphocytes such as iNKT cells (9, 10). Our findings show that in contrast to SLAMF1 and SLAMF6, Ly9 plays a negative rather than a positive role in the signaling pathways required for innate-like lymphocyte development in the thymus.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Ly9−/− mice (129xB6), provided by Dr. McKean (11), were backcrossed for 12 generations to BALB/c or C57BL/6 backgrounds. IL-4R-deficient mice (BALB/c-Il4ratm1Sz/J, IL4ra−/−) obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, were crossed with Ly9−/− mice to generate Ly9xIL-4Rα double-deficient mice (Ly9−/−IL4ra−/−). All mice were maintained in a pathogen-free facility. Experiments were conducted on animals aged 8–12-weeks-old and in compliance with institutional guidelines as well as with national laws and policies.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies using standard methods. R-PE labeled CD1d/αGalCer tetramer (Proimmune) was used to detect iNKT cells. For intracellular staining with anti-PLZF, Eomes or IFNγ, cells were made permeable with an intracellular staining buffer (eBioscience). Data were acquired using a FACSCanto II (BD) flow cytometer. Anti-mouse mAbs were obtained from BD Pharmingen, ImmunoTools and eBioscience. The mouse anti-mouse Ly9 mAb (clone Ly9.7.144, IgG1 isotype) was generated in our laboratory.

Gene expression analysis

Cells RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity RNA-to cDNA Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), while PCR reactions were assembled with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Samples were loaded onto TaqMan® Low Density Arrays and run in duplicate on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification was based on the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method using GAPDH as an endogenous control.

Lymphocyte and iNKT cell activation

IFNγ intracellular levels were measured by FACS in CD8 SP thymocytes treated ex vivo with PMA (100 ng/ml), Ionomycin (500 ng/ml) (Sigma) and Golgi Stop (BD) for 4 h. Isolated thymocytes and splenocytes (105/well) were also stimulated with different doses of the iNKT cell ligand αGalCer, (KRN7000, Enzo Life Sciences) for 48 h. Mice were i.p. injected with 250 µg of Ly9.7.144 mAb or mouse IgG1 control 48 h before administrating 6 µg of αGalCer. IL-4, IFNγ (BioLegend), and IL-17 (R&D Systems) production was detected by ELISA.

MCMV infections

Female mice were i.p. injected with 1–2×106 PFU of tissue culture-propagated MCMV (Smith strain) in 500 µl of DMEM. IFNγ levels were measured by ELISA (BioLegend). Mice were sacrificed at day 4 post-infection and thymic populations were analyzed by FACS.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups were performed with an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test with a p-value < 0.05 as the cutoff for statistical significance.

Results and Discussion

Ly9 shapes the size of the innate CD8+ T pool

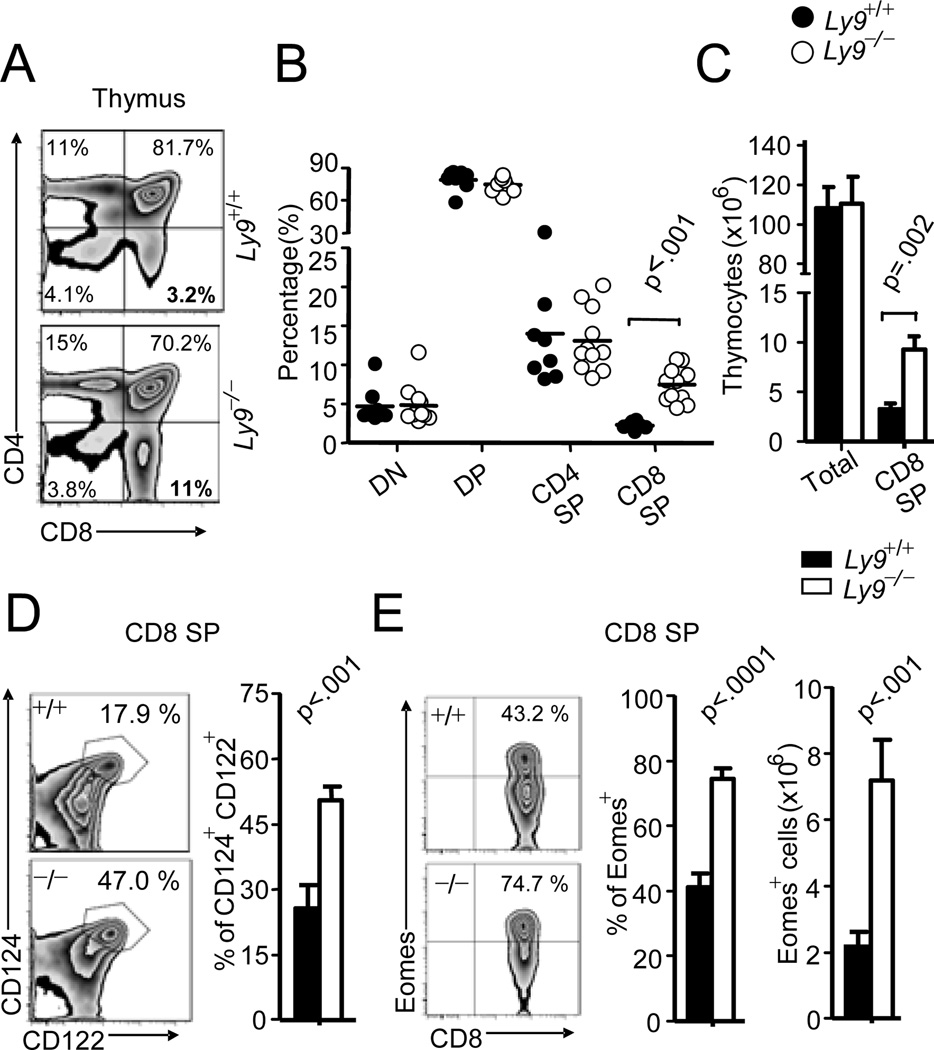

Ly9-deficient (Ly9−/−) mice on a BALB/c background developed normally but showed a striking difference in the distribution of thymocyte subsets in comparison to wt mice (Fig. 1A). An expanded population of CD8 SP thymocytes having no apparent defect in the development of the remaining thymic subsets was detected (Fig. 1B). This increased percentage of CD8 SP T cells, also apparent in cell numbers (Fig. 1C), was specific of the thymus, since it could not be observed in the blood or spleen (data not shown). A similar expanded population of thymic CD8+ T cells has also been shown to be present in several gene-deficient mice, including the Kruppel-like Factor 2 (KLF2)-, IL-2-Inducible T-cell kinase (ITK)-, CREB-Binding Protein (CBP)-, Inhibitor of DNA binding 3 (Id3)- and NF-kB1-deficient mice (reviewed in 1). Analysis of the CD8 SP T cell compartment in Ly9−/− mice confirmed that the increased CD8 SP population displayed the phenotypic characteristics of CD8+ memory-like T cells, as judged by expression of using CD122 and CD124 (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, these CD8 SP cells corresponded to a subset that expressed intermediate amounts of CD3 (CD3int), not only readily apparent in the Ly9−/− mice but also present in wt BALB/c mice (Supplemental Fig. 1A, 1B). By contrast, no differences in CD3 expression levels were detected on splenic CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Further analysis of the CD3intCD8 SP thymocytes showed that the majority of cells display the phenotype CD122highCD124highCD24lowCD62LhighCD69low, providing further evidence that these cells correspond to innate-like CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1C). In addition, we observed that the expression levels of CD122 and CD124 were higher in the CD3intCD8 SP thymocytes from the Ly9-deficient mice compared to those of the wt mice (Supplemental Fig. 1C). The observation that CD8+ innate-like T cells expressed intermediate amounts of CD3 has not been noted in previous studies. Consistent with this phenotype, the Ly9-deficient thymocyte population contained a more than three-fold higher number of CD8 SP cells expressing Eomes, a transcription factor characteristic of innate-like CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1E). This cell subset was further characterized by their negative expression of the transcription factor t-bet (Supplemental Fig. 1D). Notably, the expansion of the innate-like CD8+ T cells in Ly9-deficient mice could not be found in age-matched Ly9-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background (Supplemental Fig. 1E). Taken together the data show that the innate CD8+ T pool in the thymus is regulated by the hemophilic receptor Ly9.

Figure 1. Ly9 gene regulates the size of innate-like CD8+ T cell pool in thymus.

(A) CD4 and CD8 expression in thymocytes from wt (Ly9+/+) and Ly9-deficient (Ly9−/2212) BALB/c mice. (B) Percentage of CD8−CD4− (DN), CD8+CD4+ (DP), CD4 and CD8 (SP) cells in Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/−. (C) Cell numbers of total thymocytes and CD8 SP cells (n=6). (D) Representative data of CD124 and CD122 expression in CD8 SP thymocytes (left panels) and frequencies of CD8+ CD124+ CD122+ cells from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− (n=6) (right panel). (E) Expression of Eomes in CD8 SP thymocytes (left panels), cumulative data of percent cells (middle panel) and absolute numbers (right panel) of Eomes+ CD8 SP from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− (n=12) are shown. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. Experiments were conducted on animals aged 8–12-weeks-old.

Murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection induces a predominant pool of thymic innate-like CD8+ T cells in vivo

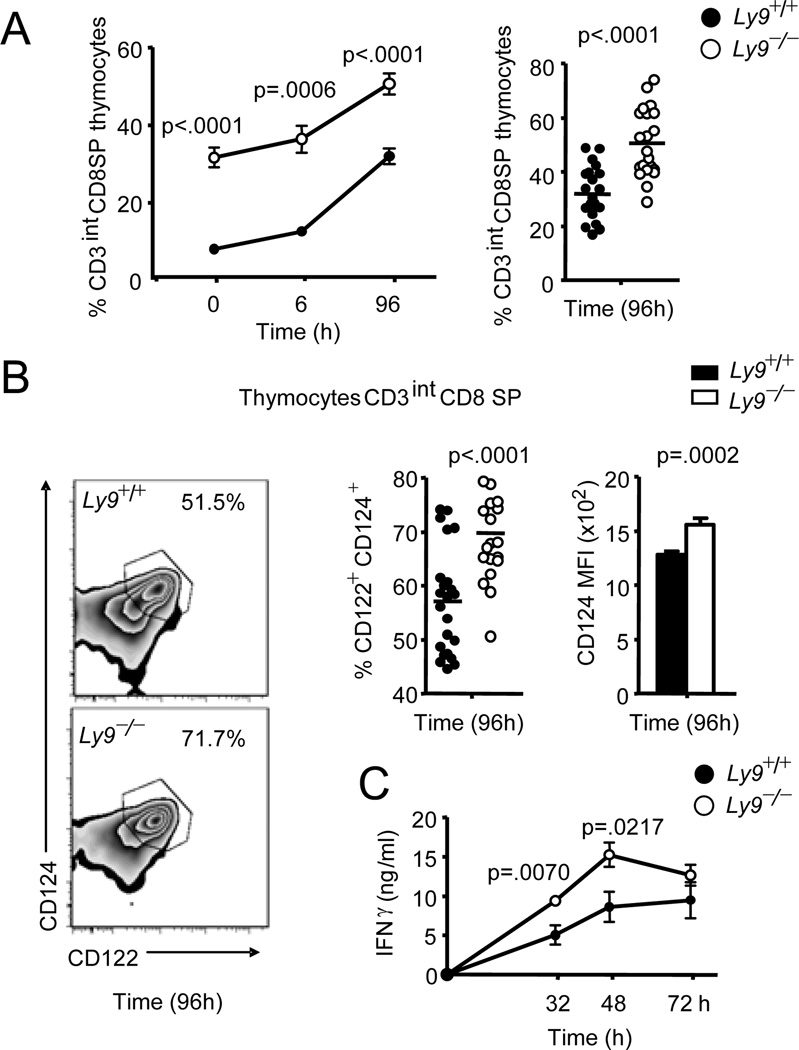

Although thymic innate memory CD8+ T cells are unlikely to play a significant role in secondary infections, they may do so during early phases of primary infections. The presence of elevated numbers of innate-like CD8+ T cells in the Ly9−/− mice, gave us the opportunity to test the behavior of these cells in response to a viral infection. Although iNKT cells have been found to participate in the initial response to MCMV infection, the role of memory-like CD8+ T cells during viral infections has not been examined (12). Thus, we determined the kinetics of memory-like CD8+ T cells in the course of a primary MCMV infection. The infection induced a rapid and large increase in the proportion of CD3intCD124highCD122high CD8 SP thymocytes, which was significantly higher in Ly9−/− versus Ly9+/+ mice (Fig. 2A, 2B). Moreover, in Ly9−/− mice these cells also expressed higher levels of CD124 compared with wt mice (Fig. 2B). An atrophy of the thymus induced by the MCMV infection, also reported by others, was observed (13). Further experiments are required to test the differential maturation and migration of thymic subsets induced by MCMV infection.

Figure 2. MCMV infection augments the ratio of the innate-like CD8+ T cells in the thymus.

(A) Frequencies of CD3int CD8+ cells among thymocytes from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− mice at the indicated time points after infection. (B) Contour plot of CD124 and CD122 expression in gated CD3int CD8+ cells (left panels), cumulative data of CD3int CD8+ CD124+ CD122+ percent cells (middle panel) and mean fluorescence intensity of CD124 expression in gated CD3int CD8+ cells from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− mice 96 h after infection (right panel). (C) Analysis of IFNγ plasma levels from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− mice (n=6 per group) at various time points after viral infection. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

A time course analysis revealed that Ly9−/− responded with higher levels of IFNγ compared with wt mice (Fig. 2C). Analysis of the viral load in different organs 96 h post-infection showed slightly lower virus in the Ly9−/− mice compared to their wt counterparts. However, these differences were not statistically significant (data not shown). Further studies will be needed to analyze the specific impact of these cells on controlling viral replication, in particular during the neonatal and early life stages before conventional memory networks are established (1). This is the first report to show that viruses are capable of inducing an important increase in the proportion of in thymic innate CD8+ cells and demonstrates that these cells may function as viral sensors in an innate cell-like manner.

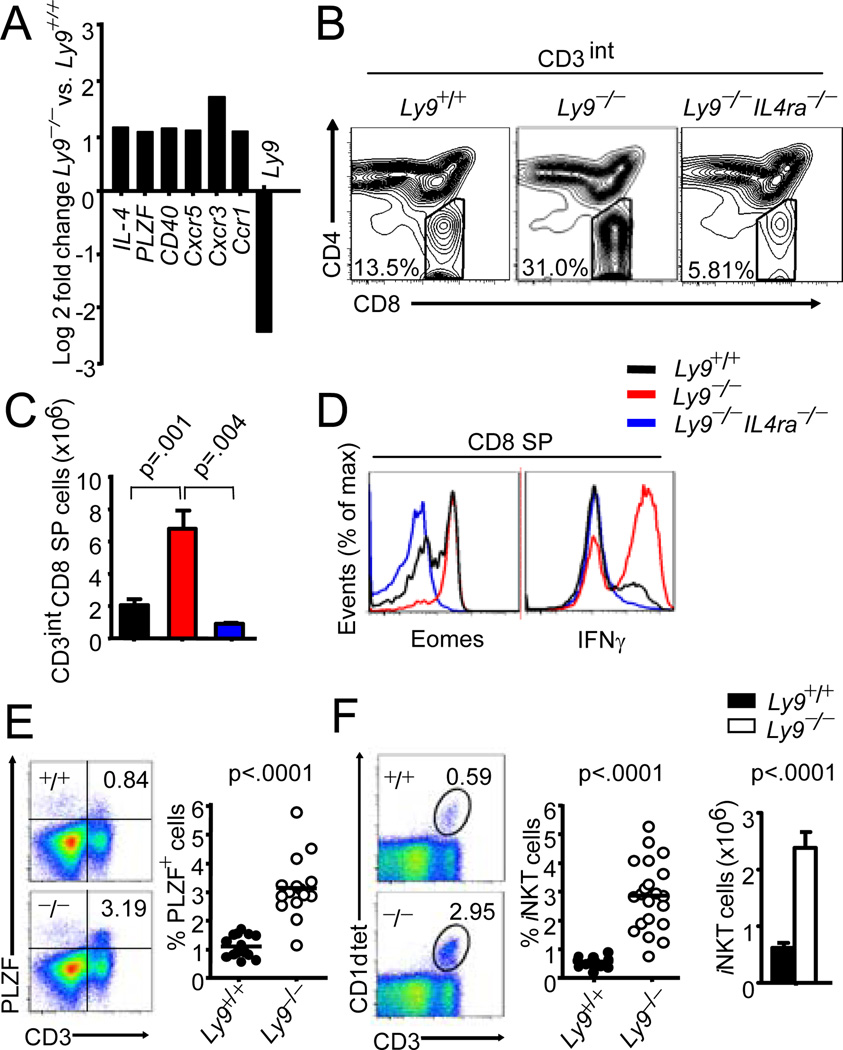

Ly9 deficiency causes the expansion of PLZF+ iNKT cells

To gain insight into the mechanism of the perturbed T-cell development observed in the Ly9-deficient mice, we performed gene expression profile analysis. The expression of 44 genes was compared between the thymi from Ly9-deficient and wt BALB/c mice (Supplemental Table I). We observed a significant up-regulation of a subset of genes associated with effector/memory CD8+ T cells and iNKT cells, such as PLZF and IL-4 (Fig. 3A). These two genes are specifically expressed by thymic iNKT cells and both are essential to their development and effector functions (4). Remarkably, the lack of Ly9 induced the up-regulation of several genes encoding the chemokine receptors Cxcr3 and Cxcr5, which are known markers of effector/memory CD8+ T cells. The most significant increase found was that of Cxcr3, which has similarly been reported to increase in the thymic innate-like CD8+ cells of KLF2-deficient mice (14). Interestingly, thymic iNKT cells express Cxcr3 that retains these cells in the thymus (15). Moreover, an increase in Cxcr5 has also been reported in the CD8 SP T cells of Id3-deficient thymocytes (16).

Figure 3. Ly9 is critical for thymic iNKT cell numbers, a major source of IL-4 required for innate-like CD8+ T cell expansion in Ly9−/− mice.

(A) Genes differentially expressed between Ly9−/− and Ly9+/+ thymocytes. (B) Contour plots of CD4 and CD8 expression in gated CD3 intermediate thymocytes (CD3int) from Ly9+/+, Ly9−/− and Ly9−/−IL4ra−/− thymocytes (C) Absolute CD3int CD8 SP cell numbers and (D) expression of Eomes and IFNγ in CD8 SP thymocytes (Black bar/line; Ly9+/+, red bar/line; Ly9−/− and blue bar/line; Ly9−/−IL4ra−/−). (E) Representative data of PLZF and CD3 expression (left panels) and cumulative data of PLZF+ percent cells from thymocytes of Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− mice (right panel). (F) Representative iNKT staining (left panel), frequency (middle panel) and absolute iNKT cell numbers (right panel) from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− thymi. Data are representative of two (A), three (B, C, D) or at least four (E, F) independent experiments.

The expansion of a population of innate CD8 SP T cells in several deficient mice (Klf2, Itk and Id3) has been attributed to an IL-4-dependent mechanism. These studies demonstrate that the acquisition of the innate T CD8+ phenotype was not an intrinsic defect in these cells, but rather stemmed from an expanded population of IL-4 producing iNKT cells. Thus, to further understand the requirements for the expansion of innate-like CD8+ T cells in Ly9−/− mice, we crossed Ly9−/− mice with others deficient in the IL-4 receptor. This completely prevented the expansion of CD3intCD8 SP cells (Fig. 3B, 3C). Moreover, the increased levels of Eomes found in the Ly9-deficient mice were undetectable in the Ly9−/−IL-4ra−/− mice (Fig. 3D). Consistent with this result, the percentage of CD8 SP T cells producing IFNγ after ex vivo activation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin, was dramatically reduced in the double-deficient cells (Fig. 3D). All these data clearly demonstrate that in a Ly9-deficiency setting IL-4 is an essential requirement for the generation of an expanded memory-like or innate-like CD8+ population. We also observed a three to six-fold increase in percentage of thymic PLZF+ and CD1d tetramer+ iNKT cells and a six-fold increase in the numbers of iNKT cells in Ly9−/− mice (Fig. 3E, 3F), indicating that expansion of the CD8 SP cells was unlikely due to an increased functional capacity of the iNKT cells, but rather resulted from an increase in the number of these cells. In contrast, we only observed a slight increase in the number of iNKT cells in the Ly9−/− C57BL/6 mice, which may be unable to support an expansion of thymic innate CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1F). The number of PLZF+ γδ T cells, a subset also involved in thymic IL-4 secretion, was not significantly altered (data not shown). Additionally, no significant alteration was found in the expression of SAP, SLAMF1 or 6 in Ly9-deficient mice (Supplemental Table I and data not shown). Thus, in contrast to the positive regulators SLAMF1 and 6, Ly9 [SLAMF3] is a negative regulator of iNKT cell development in the thymus.

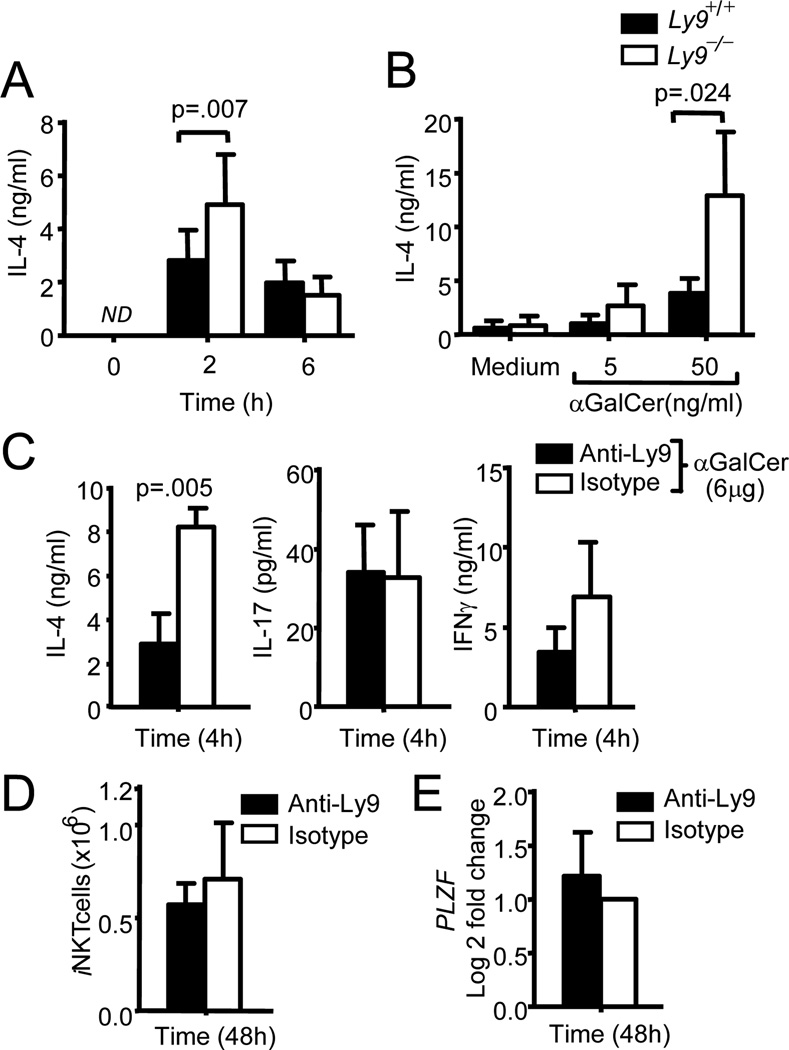

Ly9 deletion enhances cytokine production by stimulated iNKT cells

Given the important roles played by iNKT cells and IL-4 in the development of innate-like CD8+ T cells we next sought to determine the response of Ly9-deficient mice to αGalCer, a specific iNKT cell agonist. Compared with wt mice, Ly9-deficient mice presented an enhanced production of IL-4 2 h after in vivo injection with αGalCer (Fig 4A). Consistent with our in vivo results, the ex vivo activation of Ly9−/− thymocytes with αGalCer also induced significantly higher levels of IL-4 as compared with thymocytes of wt mice (Fig. 4B). In contrast, no significant difference in the in vitro production of IL-4 after αGalCer activation could be observed in splenocytes, where only a moderate increase in the iNKT cell numbers was detected in the Ly9-deficient mice and no alteration in activation markers was observed (Supplemental Fig. 1G). Thus, these results suggest that the increased levels of IL-4 largely resulted from elevated numbers of iNKT cells in Ly9-deficient mice and were likely unrelated to the hyper-reactivity of these cells.

Figure 4. Ly9 deletion enhances cytokine production in iNKT stimulated cells.

(A) IL-4 in plasma from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− mice (n=11) i.p. injected with αGalCer (6µg). Blood samples were collected at the indicated time points. (B) IL-4 levels in the culture supernatants of thymocytes from Ly9+/+ and Ly9−/− (n=7) activated with αGalCer for 48h. (C) IL-4 (left panel), IL-17 (middle panel) and IFNγ (right panel) measured in plasma from Ly9+/+ mice injected with anti-Ly9 or a matching isotype (each group treatment n=12) 48 h before administration of αGalCer. Blood was obtained 4 h after αGalCer stimulation. (D)iNKT cell numbers or (E) changes of PLZF mRNA expression levels after anti-Ly9 or a matching isotype treatment for 48 hours previous to αGalCer administration. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Importantly, we demonstrate here that IL-4 production could be modulated by the in vivo treatment with an anti-Ly9 mAb. The injection of wt mice with anti-Ly9 monoclonal antibody (Ly9.7.144) was able to induce a significant decrease in the production of IL-4 but not in IL-17 or IFNγ after αGalCer administration (Fig. 4C). No effect of this mAb was observed in Ly9-deficient mice, supporting its specificity. This decrease in IL-4 production was most likely due to the agonistic effect of this mAb. This non-cytotoxic mAb did not significantly affect the numbers of iNKT cells or the levels of PLZF in thymus (Fig. 4D, 4E). We have previously shown that mAbs against human Ly9 (CD229) negatively regulate TCR signaling, thereby inhibiting ERK phosphorylation (17).

Collectively, our data suggest that a Ly9 deficiency may alter the threshold for thymic selection, resulting in a strong positive selection of those iNKT cells that would normally have been negatively selected, thus indirectly resulting in an augmented commitment of innate-like CD8 SP thymocytes via the production of high levels of IL-4. This proposed role of Ly9 is consistent with our observation that immature thymic iNKT cells (stage 0) expressed very high levels of Ly9 compared with mature cells (Supplemental Fig. 1H).

In conclusion, the Ly9 cell-surface receptor emerges as a uniquely important element for the modulation of innate T-cell function, acting as an inhibitory molecule that regulates iNKT development and innate-like CD8 T cell expansion. Further studies will be required to establish the molecular mechanisms by which Ly9 regulates innate lymphocyte development and effector functions. Nevertheless, this work demonstrates that Ly9 is a potential target for therapeutic intervention in diseases where iNKT cell numbers play a relevant role including cancer, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Lázaro and J. de Salort for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia through grants SAF2009-7071 (P. Engel) and SAF2011 (to A. Angulo) nd by a grant from the NIH (PO-092510 to PE and CT). X. Romero was supported by the Beatriu de Pinos fellowship (2010 BP-B).

Abbreviations used

- SLAM

signaling lymphocytic activation molecule

- SAP

SLAM-associated protein

- iNKT

invariant natural killer T

- PLZF

promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger

- Eomes

eomesodermin

- αGalCer

alpha-galactosylceramide

- MCMV

murine cytomegalovirus

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Lee YJ, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Alternative memory in the CD8 T cell lineage. Trends. Immunol. 2011;32:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreich MA, Odumade OA, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. T cells expressing the transcription factor PLZF regulate the development of memory-like CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:709–716. doi: 10.1038/ni.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai D, Zhu J, Wang T, Hu-Li J, Terabe M, Berzofsky JA, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. KLF13 sustains thymic memory-like CD8(+) T cells in BALB/c mice by regulating IL-4-generating invariant natural killer T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1093–1103. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alonzo ES, Sant'Angelo DB. Development of PLZF-expressing innate T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griewank K, Borowski C, Rietdijk S, Wang N, Julien A, Wei DG, Mamchak AA, Terhorst C, Bendelac A. Homotypic interactions mediated by Slamf1 and Slamf6 receptors control NKT cell lineage development. Immunity. 2007;27:751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horai R, Mueller KL, Handon RA, Cannons JL, Anderson SM, Kirby MR, Schwartzberg PL. Requirements for selection of conventional and innate T lymphocyte lineages. Immunity. 2007;27:775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kageyama R, Cannons JL, Zhao F, Yusuf I, Lao C, Locci M, Schwartzberg PL, Crotty S. The Receptor Ly108 Functions as a SAP Adaptor-Dependent On-Off Switch for T Cell Help to B Cells and NKT Cell Development. Immunity. 2012;36:986–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verykokakis M, Boos MD, Bendelac A, Kee BL. SAP protein-dependent natural killer T-like cells regulate the development of CD8(+) T cells with innate lymphocyte characteristics. Immunity. 2010;33:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero X, Zapater N, Calvo M, Kalko SG, de la Fuente MA, Tovar V, Ockeloen C, Pizcueta P, Engel P. CD229 (Ly9) lymphocyte cell surface receptor interacts homophilically through its N-terminal domain and relocalizes to the immunological synapse. J.Immunol. 2005;174:7033–7042. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sintes J, Vidal-Laliena M, Romero X, Tovar V, Engel P. Characterization of mouse CD229 (Ly9), a leukocyte cell surface molecule of the CD150 (SLAM) family. Tissue Antigens. 2007;70:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham DB, Bell MP, McCausland MM, Huntoon CJ, van Deursen J, Faubion WA, Crotty S, McKean DJ. Ly9 (CD229)-deficient mice exhibit T cell defects yet do not share several phenotypic characteristics associated with SLAM- and SAP-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2006;176:291–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyznik AJ, Tupin E, Nagarajan NA, Her MJ, Benedict CA, Kronenberg M. The mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J. Immunol. 2008;181:4452–4456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price P, Olver SD, Gibbons AE, Teo HK, Shellam GR. Characterization of thymic involution induced by murine cytomegalovirus infection. Immunology and Cell Biology. 1993;71:155–165. doi: 10.1038/icb.1993.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinreich MA, Takada K, Skon C, Reiner SL, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. KLF2 transcription-factor deficiency in T cells results in unrestrained cytokine production and upregulation of bystander chemokine receptors. Immunity. 2009;31:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drennan MB, Franki AS, Dewint P, Van Beneden K, Seeuws S, van de Pavert SA, Reilly EC, Verbruggen G, Lane TE, Mebius RE, et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR3 retains invariant NKT cells in the thymus. J Immunol. 2009;183:2213–2216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyazaki M, Rivera RR, Miyazaki K, Lin YC, Agata Y, Murre C. The opposing roles of the transcription factor E2A and its antagonist Id3 that orchestrate and enforce the naive fate of T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:992–1001. doi: 10.1038/ni.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martín M, Del Valle JM, Saborit I, Engel P. Identification of Grb2 as a novel binding partner of the signaling lymphocytic activation molecule-associated protein binding receptor CD229. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5977–5986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.5977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.