A plant phospholipase D (PLDα1) is activated by salt stress, and the produced lipid phosphatidic acid (PA) binds to a microtubule-associated protein MAP65-1. The PA and MAP65-1 interaction is essential for the regulation of microtubule organization and salt tolerance. This finding couples lipid signaling to the cytoskeleton and reveals a lipid-mediated signaling pathway that responds to stress.

Abstract

Membrane lipids play fundamental structural and regulatory roles in cell metabolism and signaling. Here, we report that phosphatidic acid (PA), a product of phospholipase D (PLD), regulates MAP65-1, a microtubule-associated protein, in response to salt stress. Knockout of the PLDα1 gene resulted in greater NaCl-induced disorganization of microtubules, which could not be recovered during or after removal of the stress. Salt affected the association of MAP65-1 with microtubules, leading to microtubule disorganization in pldα1cells, which was alleviated by exogenous PA. PA bound to MAP65-1, increasing its activity in enhancing microtubule polymerization and bundling. Overexpression of MAP65-1 improved salt tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana cells. Mutations of eight amino acids in MAP65-1 led to the loss of its binding to PA, microtubule-bundling activity, and promotion of salt tolerance. The pldα1 map65-1 double mutant showed greater sensitivity to salt stress than did either single mutant. These results suggest that PLDα1-derived PA binds to MAP65-1, thus mediating microtubule stabilization and salt tolerance. The identification of MAP65-1 as a target of PA reveals a functional connection between membrane lipids and the cytoskeleton in environmental stress signaling.

INTRODUCTION

The plasma membrane is a biological barrier that separates a cell from the external environment. It is also a location where extracellular stimuli are sensed. When plants are exposed to saline conditions, Na+ enters the root cells via cation channels or Na+ transporters (Horie and Schroeder, 2004; Munns and Tester, 2008). Most of the Na+ that enters root cells is pumped back out via plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporters or is sequestered into vacuoles, which are regulated by a series of signal molecules, such as the salt overly sensitive pathway (Zhu, 2003; Apse and Blumwald, 2007).

Relatively little is known about the function of lipids in salinity response and tolerance. Recent work has demonstrated that phospholipase D (PLD) and its hydrolysis product, phosphatidic acid (PA), function as lipid messengers in response to developmental and environmental stimuli (Munnik, 2001; Wang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). The expression of several PLD genes is induced by salt stress (Katagiri et al., 2001). A lack of PLDα1 and PLDα3 leads to low PA accumulation and results in sensitivity to salinity (Hong et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2010). A salt-induced increase in PA levels has been suggested to affect the transcript level of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which plays important roles in cell growth and the stress response (Hong et al., 2008). Moreover, mitogen-activated protein kinase 6 (MPK6) has been identified as a direct target of PA in salinity signaling. PA binds to and activates MPK6, which phosphorylates the SOS1 transporter in vitro. Yu et al. (2010) found that a pldα1 mutant had a lower level of MPK6 activity and more Na+ accumulation in its leaves than did wild-type plants. These findings have established a link between lipid signaling, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, and salt tolerance (Morris, 2010).

Microtubule organization and biogenesis is important to cell growth, division, and the stress response (Dixit and Cyr, 2004; Ehrhardt and Shaw, 2006; Hashimoto and Kato, 2006; Shoji et al., 2006; Rodríguez-Milla and Salinas, 2009). The cytoplasmic accumulation of salt caused by SOS1 mutation induces dysfunctions of the cortical microtubules (Shoji et al., 2006). During the response to salt stress, plant cells undergo microtubule depolymerization and reorganization, and both processes are believed to be essential for plant survival under salt stress (Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011). Microtubule organization is regulated by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) (Dixit and Cyr, 2004; Sedbrook, 2004). Members of the MAP65 family participate in the polymerization and bundling of microtubules (Smertenko et al., 2004; Van Damme et al., 2004a; Mao et al., 2005). The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains nine MAP65-related genes with diverse features and functions (Hussey et al., 2002). MAP65s show different colocalizations with microtubule arrays, as observed using protein immunolocalization. MAP65-1, MAP65-2, MAP65-5, and MAP65-8 are predominantly associated with cortical microtubules. MAP65-3 and MAP65-4 are associated with mitotic microtubules and prophase spindle microtubules, respectively, while MAP65-6 colocalizes with mitochondria, as well as interphase and mitotic microtubules, and enhances the resistance of microtubules to NaCl in vitro (Van Damme et al., 2004b; Mao et al., 2005; Smertenko et al., 2008; Lucas et al., 2011).

MAP65-1 binds to and bundles microtubules by forming ∼25-nm cross-bridges between microtubules to stabilize them (Chang-Jie and Sonobe, 1993; Smertenko et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2005; Lucas et al., 2011). Moreover, the microtubule-bundling activity of MAP65-1 is modulated by MAPK during cytokinesis. The phosphorylation by MAPK regulates both the binding of MAP65-1 to microtubules and its targeting to the midzone, thereby affecting mitosis (Smertenko et al., 2006). Mutations in MAPs or MAPKs lead to a wide range of cellular phenotypes related to growth, such as branching of root hairs and swelling of diffusely growing epidermal cells (Lucas and Shaw, 2008; Sedbrook and Kaloriti, 2008). However, little is known about how microtubules are regulated in response to salt stress.

A 90-kD protein from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) has been identified as a MAP with PLD activity. Screening an Arabidopsis cDNA expression library with an antibody against the 90-kD protein produced a partial clone encoding PLDδ (Gardiner et al., 2001). Arabidopsis PLDδ is associated with the plasma membrane, as revealed by immunoblotting of proteins from membrane fractions and transient expression of yellow fluorescent protein–fused PLDδ in tobacco leaves (Wang and Wang, 2001; Guo et al., 2011). Thus, PLD may be a linker connecting microtubules with the plasma membrane (Paredez et al., 2006).

On the other hand, pharmacological experiments have shown that treating tobacco cells with n-butanol, which is transferred by PLD to the phosphatidyl moiety of a phospholipid to produce a phosphatidylbutanol instead of PA, leads to dissociation of cortical microtubules from the membrane (Dhonukshe et al., 2003). Adding PA reduces the effect of n-butanol on microtubule organization (Dhonukshe et al., 2003; Komis et al., 2006). These observations indicate that PA plays important roles in the regulation of microtubule organization. However, key questions remain: Genetic evidence for and the molecular mechanism by which PLD interacts with microtubules have yet to be established; whether PLD interacts directly with microtubules, indirectly via PA or a complex, or acts as a signal molecule for the regulation of microtubule organization needs to be determined; and, finally, how the interactions between lipids and microtubules regulate salt tolerance must be elucidated.

Here, we report that the lipid messenger PA is a regulator cross-linking the plasma membrane and microtubules in response to salt stress. We show that ablation of PLDα1 renders cortical microtubules unstable under salt stress. PA derived from PLDα1 binds to MAP65-1 and promotes its microtubule-polymerizing and bundling activity to stabilize microtubules, thereby playing an essential role in plant adaptation to salt stress.

RESULTS

PLDα1 Is Essential for Reorganization of Microtubules in Response to Salt Stress

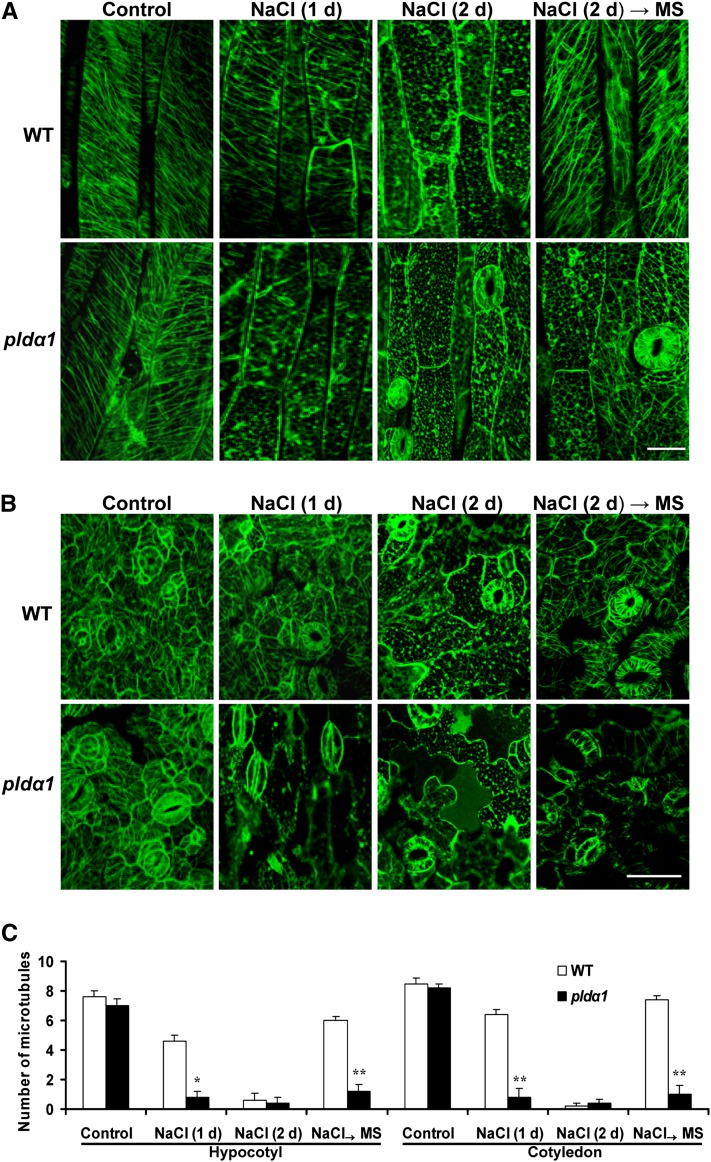

Both PLD and cortical microtubules play essential roles in the response to salt stress (Hashimoto and Kato, 2006; Munnik and Testerink, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2010). To investigate whether PLD and microtubules interact in response to salt stress, we compared cortical microtubule patterns between the wild type and salt-sensitive pldα1 mutant in Arabidopsis (Bargmann et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2010). The 35S:GFP-TUA6 (for green fluorescent protein fused to the Arabidopsis alfa-tubulin 6 isoform) transgene was crossed into the pldα1 mutant background to visualize microtubules. The homozygous pldα1 mutant with GFP-TUA6 was confirmed by PLDα1 protein and activity determination, as well as GFP observation (Figures 1A and 1B; see Supplemental Figure 1 online). To quantify the effect of salt stress on the stability of cortical microtubules in wild-type and pldα1 mutant Arabidopsis, we counted the number of cortical microtubules in epidermal cells of hypocotyls and cotyledons (Figure 1C). Under normal conditions, wild-type and pldα1 plants showed no obvious differences with respect to microtubule organization and density (Figures 1A to 1C). However, treatment of pldα1 plants with 50 mM NaCl for 1 d induced massive depolymerization of microtubules, forming fewer microtubules than in wild-type plants (Figures 1A to 1C). When NaCl treatment was prolonged for 2 d, wild-type cells also displayed disorganized microtubules. However, organization was recovered in wild-type plants but not in plda1 plants after NaCl was removed from the growth medium (Figures 1A to 1C) or in seedlings that were exposed to NaCl treatment for 7 d (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). These results indicate that PLDα1 is involved in reorganizing microtubules after depolymerization induced by salt stress.

Figure 1.

Knockout of PLDα1 Results in Depolymerization of Cortical Microtubules under Salt Stress.

(A) and (B) Confocal images of GFP-TUA6–labeled cortical microtubules. Seven-day-old wild-type (WT) and pldα1 seedlings were grown in MS medium with 50 mM NaCl for 1 or 2 d. For recovery experiments, seedlings treated with NaCl for 2 d were transferred to MS medium for another 2 d before observation. The epidermal cells in hypocotyls (A) and the cotyledon (B) were observed. Bars = 10 µm for hypocotyls and 100 µm for cotyledons.

(C) Quantification of cortical microtubules. The data shown in (A) and (B) were quantified by Image Tool software (n > 40 cells from three samples). The number of cortical microtubules was determined by counting the microtubules across a fixed line (∼10 μm in hypocotyl and ∼20 μm in cotyledon) vertical to the orientation of most of the cortical microtubules of the cell. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the wild type at the same conditions. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Error bars represent ±sd.

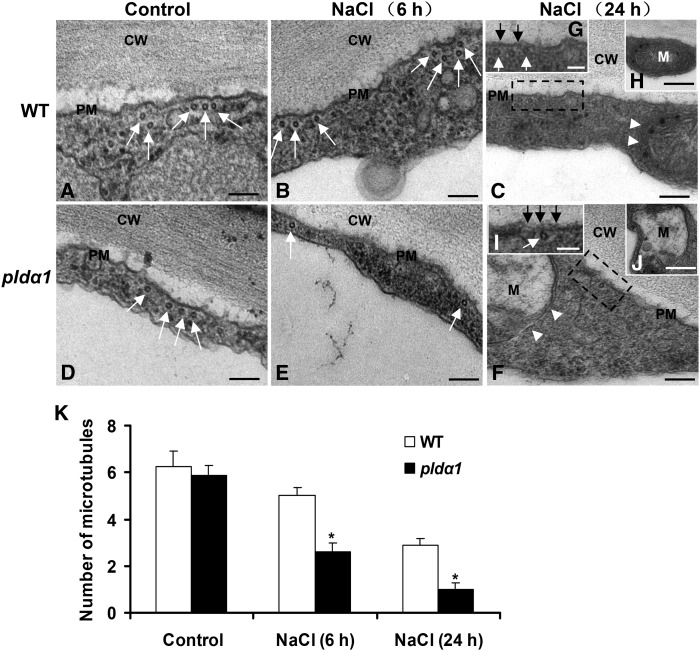

Microtubules of hypocotyl epidermal cells were further visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The cortical microtubules were associated with the plasma membrane in both wild-type and pldα1 cells (Figures 2A and 2D). These microtubules were bundled with a spacing distance of ∼25 nm. Treatment of pldα1 plants with NaCl for 6 h led to fewer microtubules near the plasma membrane than did treatment of wild-type cells (Figures 2E and 2K). Longer (24 h) salt treatment induced structural changes in the plasma membrane and mitochondria in pldα1 cells (Figures 2F, 2I, and 2J). Compared with pldα1 cells, the microtubule organization, plasma membrane, and mitochondrial structures of wild-type cells remained normal under salt treatment (Figures 2C, 2G, and 2H). Taken together, these results indicate that PLDα1 is essential for reorganizing microtubules in response to salt stress.

Figure 2.

Transmission Electron Micrographs of Cortical Microtubules in Hypocotyl Epidermal Cells.

(A) to (C) Microtubules in wild-type (WT) cells. Seedlings were treated with 50 mM NaCl for 6 h (B) or 24 h (C) before TEM observation.

(D) to (F) Microtubules in pldα1 cells. Salt treatment was the same as in wild-type seedlings.

(G) to (J) Detailed visualization of cell structures in (C) and (F).

(G) and (I) Enlargements of the region of the plasma membrane boxed with dashed lines in (C) and (F), respectively.

(H) and (J) The intact mitochondria indicated with white arrowheads in (C) and (F), respectively.

CW, cell wall; M, mitochondria; PM, plasma membrane. Bars = 100 nm in (A) to (F), 50 nm in (G) and (I), and 200 nm in (H) and (J). White arrows denote microtubules, and black arrows denote the PM.

(K) Quantification of cortical microtubules of the wild type and pldα1 shown in (A) to (F). The number of cortical microtubules in a fixed unit (∼1 μm) was determined by counting the microtubules beneath the plasma membrane (n > 30 cells from three samples). The asterisk indicates that the mean value is significantly different from that of the wild type at the same conditions. P < 0.05. Error bars represent ±sd.

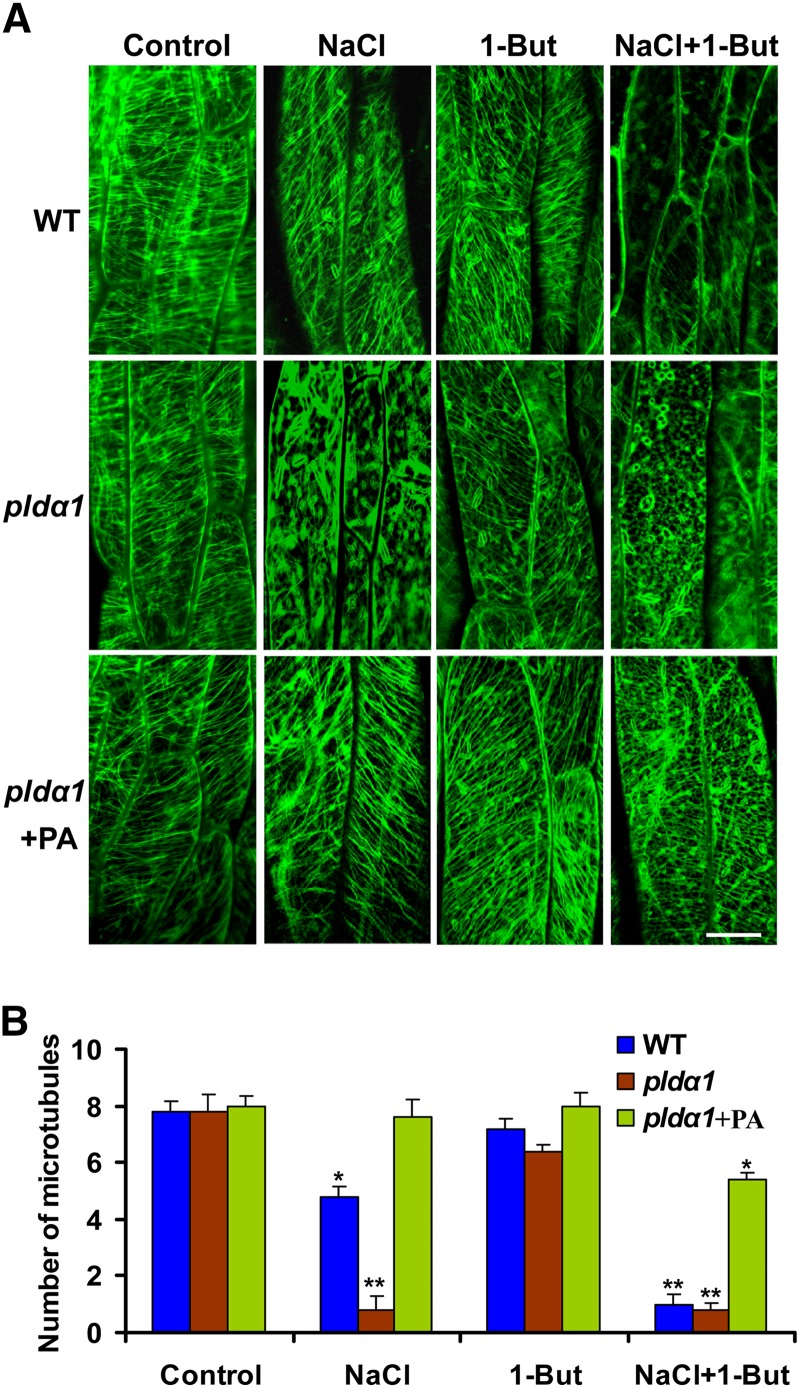

PA Alleviates NaCl-Induced Microtubule Depolymerization

PLD signaling in animal and plant cells is mediated by its product PA (Testerink and Munnik, 2005; Wang et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). To test if PLDα1-derived PA is involved in regulating microtubule organization in Arabidopsis, we investigated the effect of PA on microtubule organization. When 20 μM palmitoyl-linoleoyl PA (16:0-18:2 PA), a PA species increased in wild-type cells by NaCl treatment (Yu et al., 2010), was added to full-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium before NaCl treatment, the salt-disrupted microtubule organization in pldα1 cells was recovered (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

PA Regulates the Organization of Cortical Microtubules.

(A) Effect of PA and 1-butanol (1-But) on the organization of cortical microtubules in hypocotyl epidermal cells. Seedlings were treated with 0.1% 1-butanol together with 50 mM NaCl for 24 h. For PA treatment, the pldα1 seedlings were grown on MS medium containing 20 µM PA before the treatment. The GFP-TUA6–labeled cortical microtubules were analyzed by confocal microscopy. WT, the wild type. Bar = 10 µm.

(B) Quantification of cortical microtubules in hypocotyl epidermal cells shown in (A) by Image Tool software (n > 40 cells from three samples). The number of cortical microtubules was determined by counting the microtubules across a fixed line (∼10 μm) vertical to the orientation of the most cortical microtubules of the cell. The asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the control. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Error bars represent ±sd.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

The compound 1-butanol promotes phosphatidylalcohol production instead of PA from PLD, thereby reducing the amount of PA in cells (Munnik et al., 1995). Therefore, we used 1-butanol to further test the effect of PA on microtubule organization. Treatment with 1-butanol at 0.1% had no obvious effect on microtubule arrays in wild-type and pldα1 cells. However, a higher concentration of 1-butanol (0.4%) or cotreatment with NaCl and 1-butanol (0.1%) led to serious microtubule depolymerization and root elongation in both the wild type and pldα1 (Figures 3A and 3B; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). The application of PA alleviated the microtubule depolymerization in pldα1 cells caused by 1-butanol in both the presence and absence of exogenous NaCl (Figures 3A and 3B). By contrast, the compound 2-butanol, which is not a substrate of PLD, had no obvious effect on cortical microtubules (see Supplemental Figures 3A and 3B online). These results suggest that PA derived from PLDα1 acts as a positive regulator in stabilizing microtubules against depolymerization during NaCl stress.

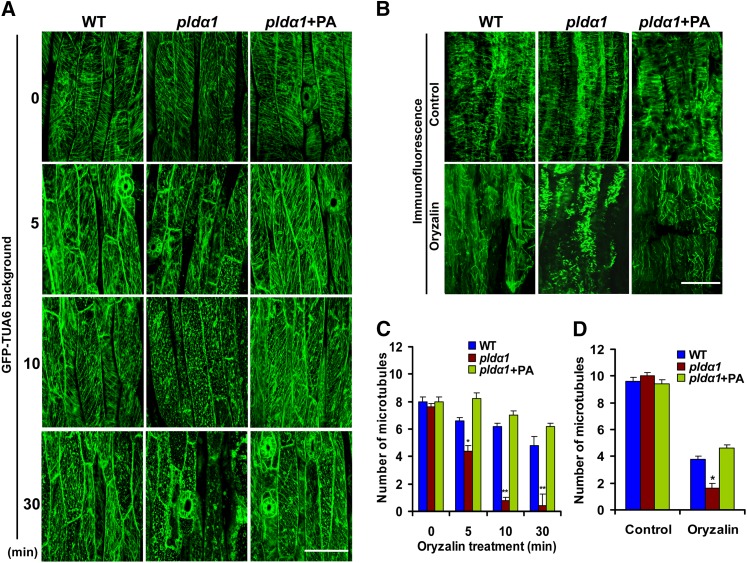

PLDα1/ PA Regulate Microtubule Stability

We further explored PLDα1- and PA-regulated microtubule organization by employing the microtubule-disrupting reagent oryzalin. Treatment with oryzalin led to a transient increase in PLDα activity (see Supplemental Figure 4A online). In pldα1 cells treated with 10 μM oryzalin, the cortical microtubules began to undergo depolymerization at 5 min. After oryzalin treatment for 10 min, the vast majority of cortical microtubules were disrupted. By contrast, the cortical microtubules in wild-type cells were largely unaffected after oryzalin treatment for at least 10 min. Longer treatment (30 min) with oryzalin started to disrupted cortical microtubules in wild-type cells (Figures 4A and 4C). Application of PA to the medium increased microtubule resistance to oryzalin in pldα1 cells (Figures 4A and 4C). These results support the notion that PA stabilizes the microtubules.

Figure 4.

pldα1 Cells Are Hypersensitive to the Microtubule-Disrupting Drug Oryzalin.

(A) Visualization of GFP-TUA6–labeled cortical microtubules of hypocotyl cells after oryzalin treatment. The cortical microtubules were observed by confocal microscopy after incubation with 10 µM oryzalin with or without PA for 0 to 30 min. WT, the wild type. Bar = 50 µm.

(B) Visualization of immunofluorescence-labeled cortical microtubules of hypocotyl cells after oryzalin treatment. Bar = 50 µm.

(C) and (D) Quantification of cortical microtubules of the wild type and pldα1 in hypocotyl epidermal cells as treated in (A) and (B), respectively, by Image Tool software (n > 40 cells from at least three seedlings). The number of cortical microtubules was determined by counting the microtubules across a fixed line (∼10 μm) vertical to the orientation of most of the cortical microtubules of the cell. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the wild type. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Error bars represent ±sd.

To test whether a GFP-TUA6 tag in the transgenic seedlings would affect microtubules, we investigated the microtubule pattern by treating seedlings with oryzalin, followed by immunofluorescence labeling using tubulin antibody. A change in microtubule pattern was found, which was similar to that found in GFP-TUA6 labeling (Figures 4B and 4D), suggesting that the GFP-TUA6 tag did not affect microtubules.

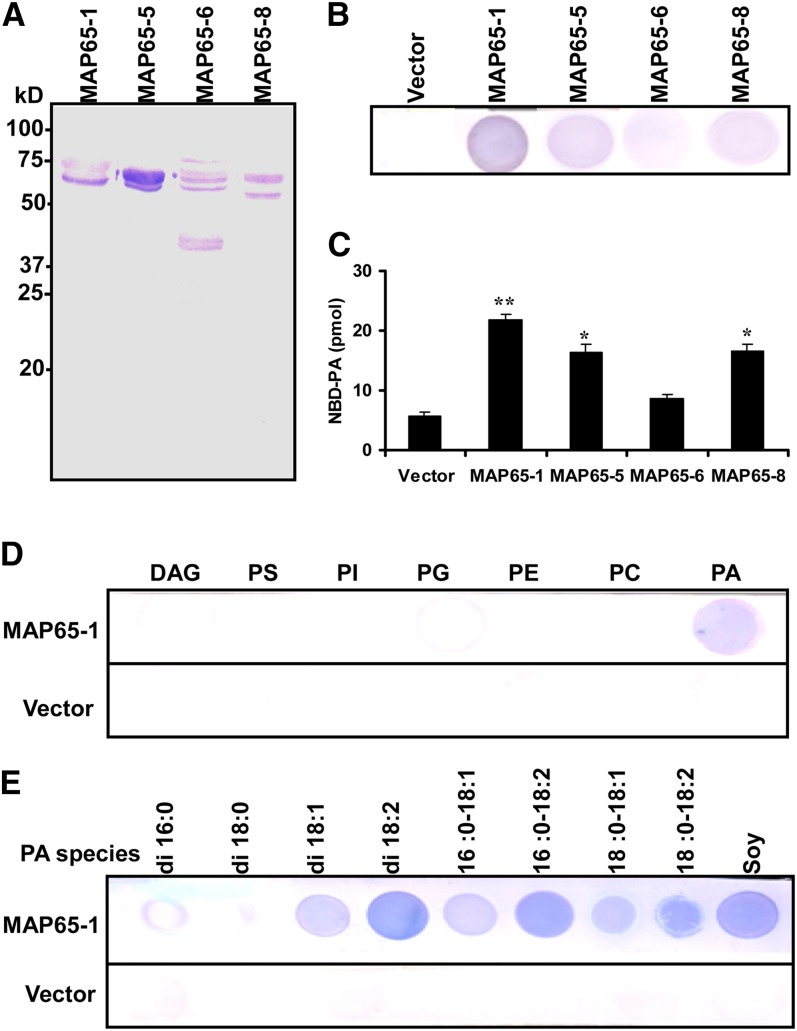

PA Binds to MAP65-1

To investigate the mechanism by which PA stabilizes microtubules, we examined the interaction between PA and MAPs. Members of the MAP65 family that participate in microtubule organization (i.e., those members predominantly associated with cortical microtubules) were chosen for the lipid binding test. We expressed recombinant proteins of MAP65-1, MAP65-5, MAP65-6, and MAP65-8 containing a 6-His tag at the N terminus in Escherichia coli and then purified them. Although immunoblotting analyses indicated that there was some degradation in MAP65 fusion proteins (Figure 5A), the filter binding results showed that PA bound to MAP65-1 more strongly than to other MAP65s (Figure 5B). The PA–MAP65 interactions were further examined by liposome immunoprecipitation. Equal amounts of purified MAP65s were incubated with lipid vesicles composed of fluorescent 12[(7-nitro-2-1, 3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]dodecanoyl phosphatidic acid (NBD-PA) and phosphatidyl choline (PC) at a 2:1 ratio. The bound NBD-PA was pelleted by immunoprecipitation and quantified using a fluorescence spectrophotometer. As shown in Figure 5C, among these MAP65s, MAP65-1 showed the strongest binding to PA.

Figure 5.

PA Binds to MAP65-1.

(A) Immunoblot of His-tagged MAP65s expressed in E. coli.

(B) PA binding to MAP65 proteins on filters. Natural PA from soybean (10 μg) was spotted onto nitrocellulose and incubated with an equal amount of purified MAP65s. The proteins bound to lipids were detected by immunoblotting using anti-His antibody. The protein from empty pET28a vectors was used as a control.

(C) Binding of MAP65 proteins to PA liposomes. Equal amounts of MAP65s were incubated with vesicles comprised of 50 µM NBD-PA and 25 µM PC, followed by immunoprecipitation and quantification by fluorescence spectrophotometry. Data are the means ± sd of five replicates. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the control (vector). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

(D) MAP65-1 protein binding to different lipids on filters. Lipids (10 μg) spotted onto nitrocellulose were incubated with MAP65-1 as described in (B). DAG, diacylglycerol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine.

(E) MAP65-1 protein binding to different PA species on filters: dipalmitoyl PA (di16:0 PA), distearoyl PA (di18:0 PA), dioleoyl PA (di18:1 PA), dilinoleoyl PA (di18:2 PA), palmitoyl-oleoyl PA (16:0-18:1 PA), palmitoyl-linoleoyl PA (16:0-18:2 PA), stearoyl-oleoyl PA (18:0-18:1 PA), stearoyl-linoleoyl PA (18:0-18:2 PA), and soy PA (l-α-PA).

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

To characterize the specificity of MAP65-1 binding with PA, different phospholipids were tested using a filter binding assay. The results showed that MAP65-1 bound to PA but not to diacylglycerol, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, or PC. Weak binding was found between MAP65-1 and phosphatidylglycerol (Figure 5D). Furthermore, MAP65-1 bound to PA in which the fatty acyl chain is palmitoyl-oleoyl (16:0-18:1), palmitoyl-linoleoyl (16:0-18:2), stearoyl-oleoyl (18:0-18:1), or stearoyl-linoleoyl (18:0-18:2), but not distearoyl (di18:0) (Figure 5E).

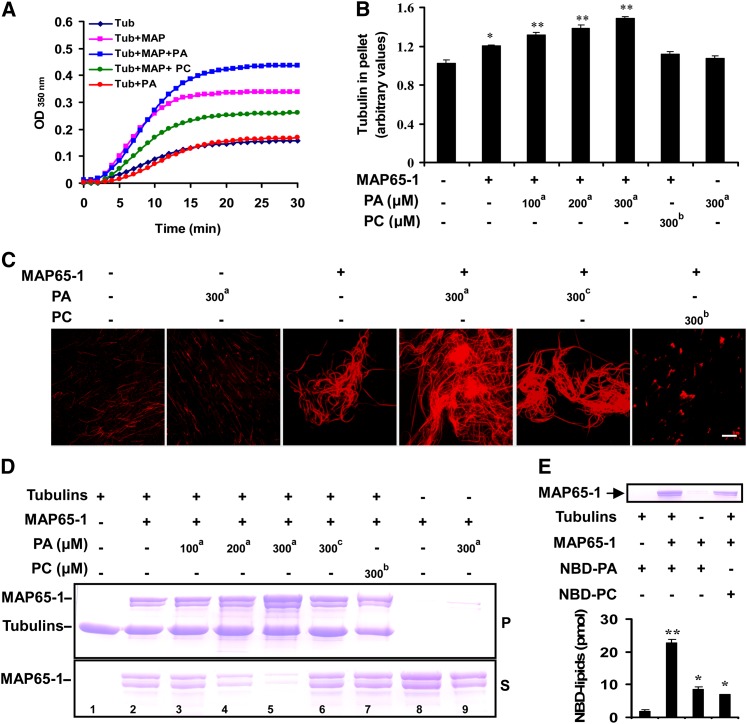

Effects of PA-MAP65-1 Binding on Microtubule Polymerization and Bundling

We next asked if PA bound to MAP65-1 affects microtubule polymerization and bundling. To address this question, the effect of PA on polymerization in the presence or absence of MAP65-1 was assessed using a turbidimetric assay. A total of 2 μM MAP65-1 was added to a solution containing 30 μM porcine brain tubulin, and the turbidity of the solution was monitored at 350 nm. As shown in Figure 6A, MAP65-1 promoted an increase in turbidity of the polymerizing microtubule mixture relative to the control (tubulin only). In the presence of MAP65-1, 16:0-18:2 PA further increased turbidity 10 min after PA was added, with the PA effect being dose dependent (Figure 6A; see Supplemental Figure 5A online). On the other hand, 16:0-18:2 PA itself had no effect on the turbidity increase in the absence of MAP65-1 (Figure 6A). Interestingly, 16:0-18:2 PC inhibited the turbidity increase caused by MAP65-1 (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

PA Mediates Microtubule Polymerization in the Presence of MAP65-1.

(A) The effect of PA on MAP65-1–induced tubulin polymerization. The turbidity of a 30 μM tubulin solution and of a tubulin solution after adding 2 μM MAP65-1 with or without 300 μM 16:0-18:2 PA was monitored at 350 nm and at 37°C. As a negative control, 300 μM 16:0-18:2 PC was used. MAP, MAP65-1; Tub, tubulin.

(B) The amount of polymerized tubulin promoted by MAP65-1 and 16:0-18:2 PA. The indicated phospholipids were added along with tubulins to polymerization buffer containing 2 μM MAP65-1 and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 100,000g, the tubulins in the pellet were quantified. Data are the means ± sd from three independent experiments. The a and b in top right corner of each number represent 16:0-18:2 PA and 16:0-18:2 PC, respectively. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the control (tubulin only). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

(C) PA increases MAP65-1 microtubule-bundling activity. Confocal images show the organization of tubulin labeled with rhodamine at 37°C. Microtubules were polymerized in a 1 μM tubulin solution only or with 300 µM 16:0-18:2 PA, 2 μM MAP65-1, MAP65-1 plus 300 μM 16:0-18:2 PA, MAP65-1 plus 300 µM di 18:0 PA, or MAP65-1 plus 300 µM 16:0-18:2 PC, respectively. The a, b, and c in the top right corner of each number represent 16:0-18:2 PA, 16:0-18:2 PC, and di 18:0 PA, respectively. Bar = 10 µm.

(D) PA promotes binding of MAP65-1 to microtubules. Paclitaxel-stabilized microtubules polymerized from 1 μM tubulin were incubated with 2 μM MAP65-1 alone or together with PA or PC, as indicated. After centrifugation, the supernatants and pellets were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE. Tubulins and MAP65-1 are indicated with arrows. The a, b, and c in the top right corner of each number represent 16:0-18:2 PA, 16:0-18:2 PC, and di 18:0 PA, respectively. P, pellets; S, supernatants.

(E) Quantification of fluorescent PA bound to MAP65-1 cosedimented with paclitaxel-stabilized microtubules. PA vesicles (including 10 μM NBD-PA and 5 μM PC) were incubated with microtubules with or without 1 μM MAP65-1. After centrifugation, the NBD-PA in the pellets was quantified by fluorescence spectrophotometry. PC vesicles (including 10 μM NBD-PC and 5 μM PC) were used as a control. Data are the means ± sd of three replicates. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the control (microtubules plus PA vesicles). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. The top panel indicates the presence of MAP65-1 in the pellets.

To examine the specificity of microtubule organization promoted by PA-MAP65-1, we tested the effect of PA on the activities of MAP65-6 and MAP65-8, which bound to PA much more weakly than did MAP65-1. Neither MAP65-6 nor MAP65-8 affected the turbidity of the microtubule mixtures, and PA did not improve their activities (see Supplemental Figure 5B online).

The increase in turbidity may have been due to an increase in the total amount of microtubule polymers or the bundling of assembled microtubules. Therefore, we assayed the amount of tubulin in pellets after centrifugation to test whether polymerization was promoted by MAP65-1 and PA. As shown in Figure 6B, the addition of MAP65-1 increased the amount of pelleted tubulin, and 16:0-18:2 PA further promoted this effect in a dose-dependent manner. However, 16:0-18:2 PC inhibited MAP65-1-promoted tubulin sedimentation (Figure 6B).

To test whether the interaction between PA and MAP65-1 affected the MAP65-1 microtubule-bundling activity, the microtubules were labeled with rhodamine and observed by confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 6C, tubulins polymerized into microtubules at 37°C. After MAP65-1 was added, the microtubules were arranged into bundles (Figure 6C). The application of 16:0-18:2 PA with MAP65-1 caused the microtubules to become hyperbundled into net-like arrays. However, 16:0-18:2 PA by itself had no effect on tubulin polymerization or microtubule bundling (Figure 6C). Di18:0 PA, which did not bind to MAP65-1 in vitro, had little effect on MAP65-1–induced microtubule bundling (Figure 6C). However, PC, the preferred substrate of PLDα1, inhibited MAP65-1–induced bundles and instead induced small bulk-like microtubules (Figure 6C). These results suggest that PA may enhance tubulin polymerization involving MAP65-1 by increasing MAP65-1 microtubule-bundling activity.

To investigate how PA promotes MAP65-1 activity, cosedimentation experiments were performed. Paclitaxel-stabilized microtubules appeared mostly in the pellets. Although the majority of MAP65-1 proteins cosedimented with the microtubules, some MAP65-1 still remained in the supernatant (Figure 6D). When 16:0-18:2 PA was added to the mixture containing MAP65-1 and microtubules, the amount of MAP65-1 protein in the pellets increased, while that in the supernatant decreased. However, di18:0 PA and 16:0-18:2 PC, which did not bind to MAP65-1 in vitro, had little effect on the amount of cosedimented MAP65-1, compared with 16:0-18:2 PA. Furthermore, little MAP65-1 was detected in the pellets after application of 16:0-18:2 PA in the absence of microtubules (Figure 6D). However, the MAP65-1 that cosedimented with PA did not lead to a turbidity increase (see Supplemental Figure 5C online). This result indicates that a PA-induced turbidity increase (Figure 6A) is majorly due to PA-promoted MAP65-1 binding to microtubules and not to the aggregation of MAP65-1 by PA.

To quantify the amount of PA bound to and cosedimented with MAP65-1, analysis of fluorescent NBD-PA was performed with a fluorescence spectrophotometer. As shown in Figure 6E, ∼22 pmol NBD-PA cosedimented with microtubules when 1 μM MAP65-1 was added to the incubation medium. In the absence of MAP65-1, only one-tenth as much NBD-PA cosedimented with the microtubules. As a negative control, the amount of NBD-PC that cosedimented with microtubules in the presence of MAP65-1 was only ∼7 pmol, which is similar to the amount of NBD-PA found in a pull-down experiment with MAP65-1 without microtubules (Figure 6E). Taken together, these data suggest that PA promotes the polymerization and bundling activities of MAP65-1 by increasing MAP65-1 binding to microtubules.

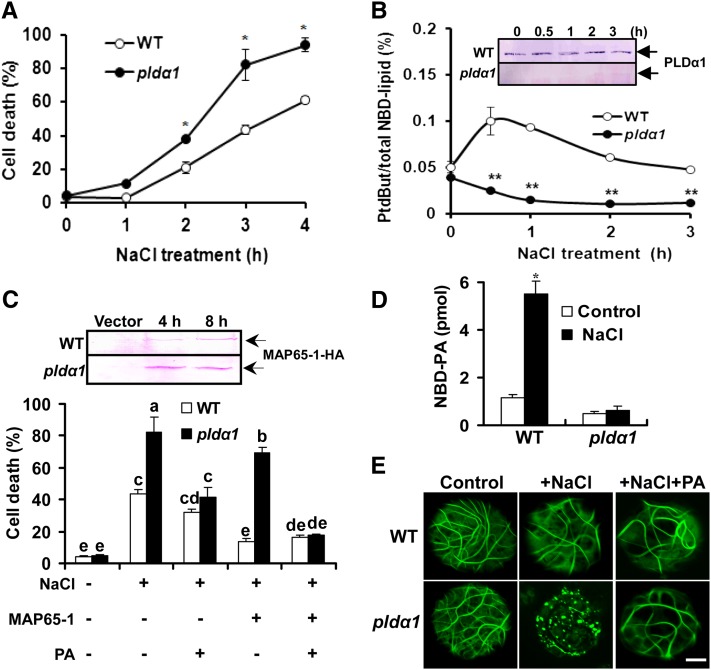

Interaction between PA and MAP65-1 Promotes Cell Tolerance to Salt Stress

To address whether the PA-MAP65-1 interaction was essential for salt tolerance in plants, we used Arabidopsis protoplasts. As shown in Figure 7A, treatment with NaCl led to cell death in a time-dependent manner, and more dead cells were found in pldα1 than in wild-type cells. To determine whether PLD is activated in response to salt stress, protoplasts were labeled with fluorescent NBD-PC as a substrate of PLDα (Munnik et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 7B, PLD activity was transiently activated in wild-type cells after NaCl treatment. The level of PLDα1 protein remained unchanged during NaCl treatment (Figure 7B, inset), suggesting that NaCl promotes the specific activity of PLDα1 (i.e., by activating rather than by increasing synthesis of the enzyme). By contrast, the PLD activity of pldα1 decreased in response to NaCl treatment (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Interaction between PA and MAP65-1 Enhances Cell Resistance to Salt Stress.

(A) Death of mesophyll protoplasts treated with 25 mM NaCl. The surviving cells were visualized by fluorescein diacetate staining. Data are the means ± sd from five replicates. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the wild type (WT) at the same conditions. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

(B) NaCl-induced PLD activity. Activity is expressed as the percentage of phosphatidylbutanol fluorescence to total NBD fluorescence. Data are the means ± sd of five replicates. Two asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the wild type at the same conditions at P < 0.01. The PLDα1 protein from protoplasts was detected by immunoblot using an anti-PLDα1–specific antibody after treatment with 25 mM NaCl (inset).

(C) The interaction between PA and MAP65-1 decreased NaCl-induced cell death. After HA-tagged MAP65-1 was overexpressed for 8 h, the protoplasts were incubated with or without 50 μM PA for 30 min at room temperature, followed by 25 mM NaCl treatment for 3 h. Data are the means ± sd from three independent experiments. Columns with different letters are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05). The expressed MAP65-1 in wild-type and pldα1 cells was detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (top panel).

(D) Quantification of NBD-PA bound to MAP65-1 in protoplasts. The NBD-PA that immunoprecipitated with MAP65-1 was quantified by thin layer chromatography fluorescence assay. Data are the means ± sd from three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates that the mean value is significantly different from that of the control at P < 0.05.

(E) Confocal images of MAP65-1-GFP overexpression in protoplasts. The protoplasts of the wild type and pldα1 were supplemented with 25 mM NaCl after overexpression or incubated with 50 μM PA for 30 min before NaCl treatment. Bar = 10 μm.

To explore the role of the interaction between PA and MAP65-1 in salt tolerance, we next expressed hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged MAP65-1 in wild-type and pldα1 protoplasts (Figure 7C, top panel). The overexpression of MAP65-1 protein resulted in decreased cell death in both the wild type and pldα1. However, the death ratio in MAP65-1– expressing cells of plda1 was approximately fivefold higher than that of the wild type. When PA was added, NaCl-induced cell death in pldα1 protoplasts overexpressing MAP65-1 decreased to a level similar to that in wild-type protoplasts (Figure 7C, bottom panel). These results suggest that the interaction between PA and MAP65-1 is required to increase salt tolerance and that PLDα1 is essential for the interaction to take place.

To further examine PA-MAP65-1 binding in cells, protoplasts expressing MAP65-1-HA were incubated with NBD-PC. The NBD-PA produced from NBD-PC hydrolysis by PLD and coprecipitated with MAP65-1 using an HA antibody was detected by thin layer chromatography. Under control conditions, the amount of PA bound to MAP65-1 in wild-type protoplasts was 1.1 pmol, which was 2.5-fold higher than that in pldα1 protoplasts. Moreover, NaCl treatment significantly enhanced the amount of PA associated with MAP65-1 in wild-type protoplasts but not in pldα1 protoplasts (Figure 7D). These data further support the conclusion that the cells’ response to salt involves PLDα1-derived PA binding to MAP65-1.

PA–MAP65-1 Interaction Promotes Salt Tolerance by Stabilizing Microtubules

We then asked whether the interaction between PA and MAP65-1 increases salt tolerance by stabilizing microtubules. We overexpressed MAP65-1 tagged with GFP (MAP65-1-GFP) in protoplasts to observe its localization with microtubules. In both wild-type and pldα1 protoplasts, MAP65-1-GFP localized to structures containing microtubule arrays, and there was no difference between these two kinds of protoplasts (Figure 7E). Salt had no apparent effect on the MAP65-1-GFP–localized structures in wild-type protoplasts, but the amount of intact microtubule arrays decreased. However, treatment with NaCl for 3 h induced dot-like structures in pldα1 protoplasts, suggesting the dissociation of MAP65-1 from microtubules and/or microtubule disorganization. Preincubation with PA prevented the NaCl-induced disruption of MAP65-1-GFP structures in pldα1 protoplasts (Figure 7E).

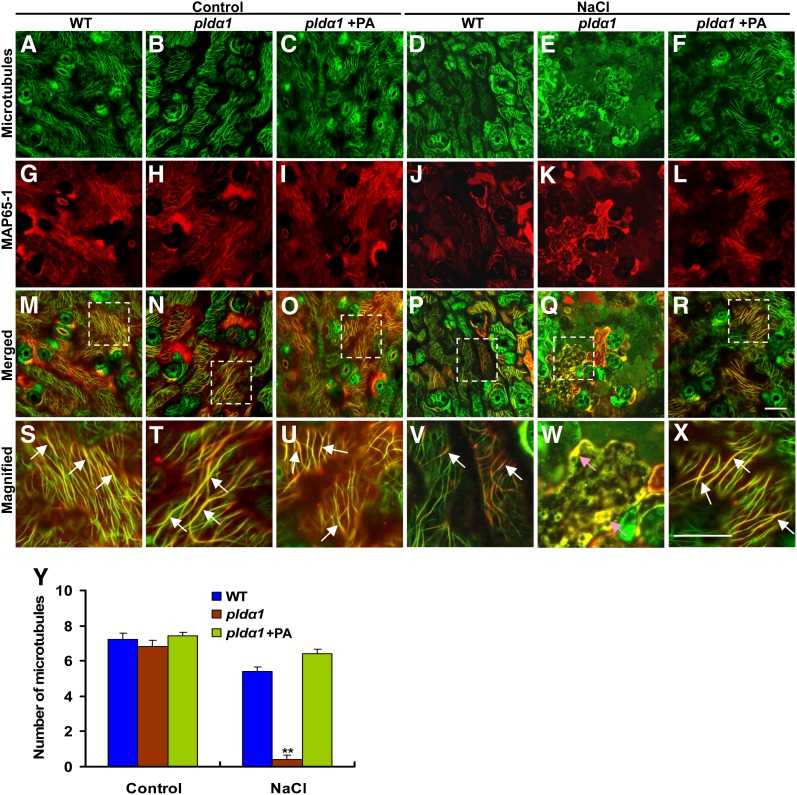

To examine if the disruption of MAP65-1-GFP localization caused by salt in pldα1 cells is due to microtubule depolymerization, MAP65-1 dissociation from microtubules, or both, we expressed mCherry-tagged MAP65-1 under the control by its native promoter, using an in planta transient transformation assay (Zhang et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 8, MAP65-1(red) colocalized with the cortical microtubules (shown by GFP-TUA6) in cotyledon pavement cells. The pattern of MAP65-1 distribution was similar in both the wild type and pldα1 mutant (Figures 8G and 8H). Salt treatment (50 mM NaCl for 24 h) induced slight microtubule depolymerization and less and weaker colocalization of MAP65-1 along intact microtubules in wild-type cells (Figures 8D and 8V). In pldα1 cells, intact microtubule arrays were almost totally lost, with dot-like structures appearing instead (Figure 8E). The yellow dots indicated by pink arrows in pldα1 cells were probably a few MAP65-1 proteins bound to depolymerized microtubules (Figure 8W). Pretreatment with PA partially recovered the array structures and MAP65-1 colocalization with microtubules in the mutant (Figures 8F and 8X).

Figure 8.

Pattern of MAP65-1 and Microtubule Localization in Cotyledons.

(A) to (L) Wild-type (WT) and pldα1 seedlings in the GFP-TUA6 background (green; [A] to [F]) were transformed with mCherry:MAP65-1 (red; [G] to [L]) using an in planta transient transformation assay (Zhang et al., 2009). Fluorescence was visualized after seedlings were exposed to 50 mM NaCl for 1 d. For PA treatment, pldα1 seedlings were grown in MS medium containing 20 μM PA for 7 d before the transient transformation assay and NaCl treatment.

(M) to (R) Colocalization of MAP65-1 with microtubules (GFP-TUA6).

(S) to (X) The detailed visualization of MAP65-1 binding to microtubules boxed in (M) to (R), respectively. White arrows point to microtubules bound by MAP65-1. Pink arrows in (W) point to the sites where MAP65-1 binds to depolymerized microtubules. Bar = 100 μm.

(Y) Quantification of cortical microtubules shown in (A) to (F) by Image Tool software (n > 40 cells from three samples). The number of cortical microtubules was determined by counting the microtubules across a fixed line (∼20 μm) vertical to the orientation of most of the cortical microtubules of the cell. Asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the wild type at the same conditions. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Error bars represent ±sd.

Collectively, these results suggest that salt stress induces microtubule depolymerization and MAP65-1 dissociation from microtubules, and PLDα1-derived PA interacts with MAP65-1, which enhances MAP65-1 activity in microtubule stabilization and consequently increases cell resistance to salt stress.

MAP65-1 Amino Acids Are Necessary for PA Binding

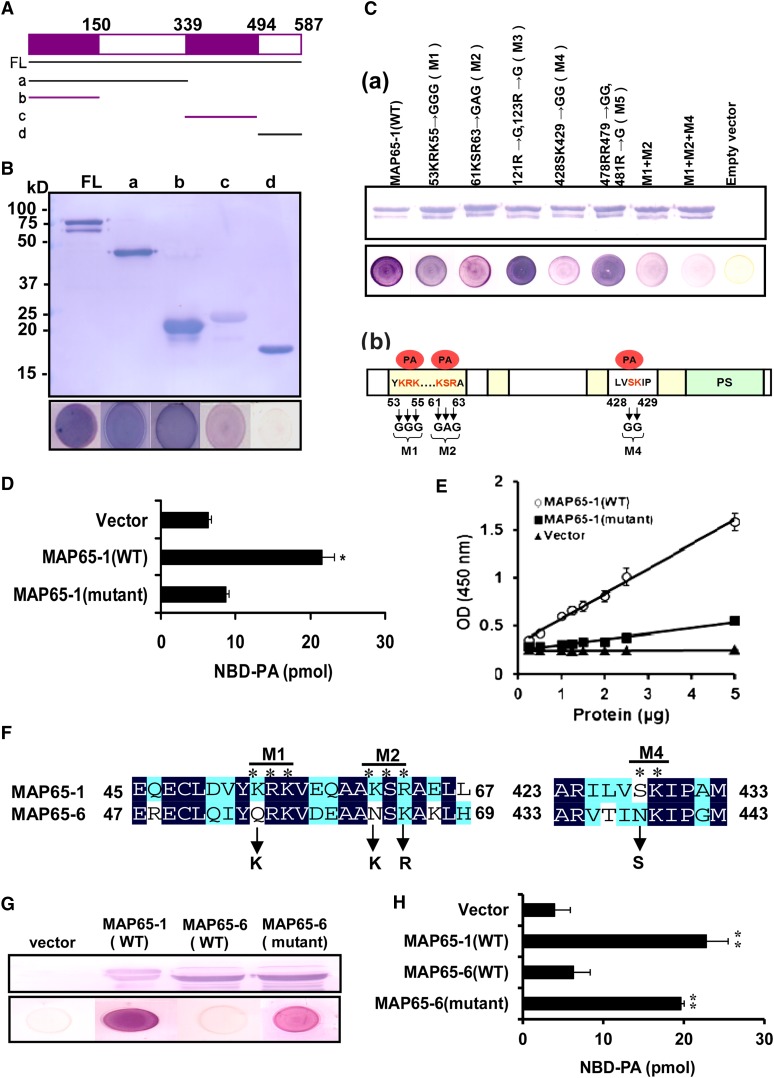

We next tried to investigate the PA binding regions in MAP65-1 by employing deletion mutagenesis. Fusion proteins consisting of different fragments (a, b, c, and d) of MAP65-1 with an attached His tag were expressed in E. coli. Results of filter binding experiments showed that the PA binding moiety resided mainly in fragments b (residues 1 to 150) and c (residues 340 to 494) (Figures 9A and 9B).

Figure 9.

Amino Acids Required for PA Binding in MAP65-1.

(A) Schematic representation of MAP65-1 fragments used for PA-MAP65-1 binding assays. FL, full-length MAP65-1 protein (residues 1 to 587); a, residues 1 to 339; b, residues 1 to 150; c, residues 340 to 494; d, residues 495 to 587.

(B) Immunoblot of His-tagged recombinant MAP65-1 fragments (top panel) and 16:0-18:2 PA binding to these fragments on filters (bottom panel).

(C) Detection of PA binding sites in MAP65-1 by site-directed mutagenesis. (a) Top panel: Immunoblot of wild-type (WT) and mutated MAP65-1 expressed in E. coli. Bottom panel: Binding of the mutated MAP65-1 proteins to PA on filters. (b) Schematic representation of MAP65-1. The coiled-coil motif and sites of phosphorylation (PS) by protein kinases are colored yellow and green, respectively. The amino acids for PA binding are highlighted (red), and the amino acid substitutions of MAP65-1 are indicated.

(D) Quantification of fluorescent NBD-PA binding to MAP65-1 proteins by immunoprecipitation. MAP65-1 (wild type) and mutated MAP65-1 (mutant, M1+M2+M4) were expressed in E. coli. The NBD-PA bound to MAP65-1 proteins was immunoprecipitated and quantified by fluorescence spectrophotometry. Data are means ± sd from five replicates. An asterisk indicates that the mean value is significantly different from that of the control (vector) at P < 0.05.

(E) Binding of MAP65-1 (wild type) and MAP65-1 (mutant) proteins to 16:0-18:2 PA by ELISA assay. PA was coated on a 96-well plate and incubated with His-tagged wild-type MAP65-1 or mutant MAP65-1 (M1+M2+M4), followed by incubation with anti-His antibody and spectrometric measurements. Data are means ± sd from five replicates.

(F) Amino acid alignment of the PA binding region in MAP65-1 and corresponding regions in MAP65-6. The mutations in the MAP65-6 sequence are indicated.

(G) PA binding to MAP65-6 on filters. Top panel: Immunoblotting of His-tagged recombinant proteins MAP65-1 (wild type), MAP65-6 (wild type), and MAP65-6 [mutant; site-directed mutagenesis is indicated in (F)]). Bottom panel: 16:0-18:2 PA binding to proteins.

(H) Quantification of fluorescent NBD-PA binding to MAP65-1 (wild type), MAP65-6 (wild type), and MAP65-6 (mutant) by immunoprecipitation. Data are means ± sd from five replicates. Two asterisks indicate that the mean value is significantly different from that of the vector at P < 0.01.

Known PA binding domains share no apparent sequence homology, but the PA recognition motif usually contains the basic amino acids Arg, His, and Lys (Li et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Some PA binding domains also contain hydrophobic residues adjacent to basic amino acids, which may subsequently associate with PA via nonionic interactions (Ghosh et al., 1996; Kooijman et al., 2007). We therefore mutated some basic amino acids in fragments b and c to Gly or Ala, as indicated in Figure 9C. The mutation of M1 (from residues 53KRK55 to 53GGG55) or M2 (from residues 61KSR63 to 61GAG63) slightly reduced the binding of PA, whereas the mutation of M4 (from residues 428SK429 to 428GG429) resulted in a dramatic decrease in PA-MAP65-1 binding. The mutation of M3 (from residue Arg-121 to Gly) or M5 (from residue Arg-123 to Gly) had no effect on PA binding. A combined mutation (M1, M2, and M4) of MAP65-1 (Figure 9C, b) caused near total loss of ability to bind PA (Figure 9C). These results were confirmed by liposome immunoprecipitation (Figure 9D) and ELISA-based assay (Figure 9E; see Supplemental Figure 6A online). As a control lipid, PC bound to neither wild-type nor mutant MAP65-1 (see Supplemental Figure 6B online).

We next mutated four amino acids in MAP65-6, which showed weak binding to PA (Figure 5B), into the PA-bound amino acids in MAP65-1 (Figure 9F). The mutant MAP65-6 showed a great increase in PA binding (Figures 9G and 9H) and remained unchanged in promoting microtubule polymerization (see Supplemental Figure 7 online). These data confirm the importance of these amino acids in PA binding and the specificity of PA-MAP65-1 in regulating microtubule organization.

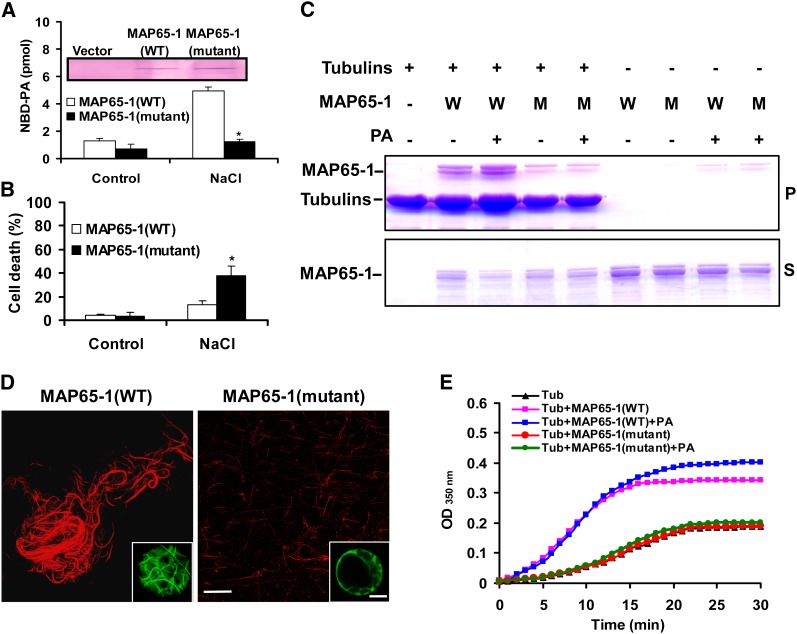

Mutation of PA Binding Domain Reduces MAP65-1 Activities in Salt Tolerance and Microtubule Organization

To investigate the effect of mutation of PA binding domain in MAP65-1 on its activities in salt tolerance and microtubule organization, we initially expressed HA-tagged wild-type and mutant MAP65-1 (bearing eight amino acid mutations) proteins in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The level of expressed proteins was similar, as measured by immunoblotting (Figure 10A, inset). In the absence of NaCl, the amount of PA bound to wild-type MAP65-1 was approximately twice that bound to mutant MAP65-1. Treatment with NaCl for 3 h resulted in an approximately threefold increase in the amount of NBD-PA bound to wild-type MAP65-1 compared with the control but had no effect on that bound to mutant MAP65-1 (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

Disruption of PA Binding Impairs MAP65-1 Activities in Microtubule Bundling and Salt Tolerance

(A) Quantification of NBD-PA bound to wild-type and mutant MAP65-1 in protoplasts. Expression of MAP65-1 (wild type [WT]) and MAP65-1 (mutant; simultaneous mutations of M1, M2, and M4 as indicated in Figure 9) proteins overexpressed in protoplasts was detected by anti-HA antibody (inset). After proteins were expressed, protoplasts were incubated with NBD-PC before NaCl treatment. The NBD-PA from hydrolysis of NBD-PC was precipitated by anti-HA antibody. Data are the means ± sd from three independent experiments. The asterisk indicates that the mean value is significantly different from that of MAP65-1 (wild type) at P < 0.05.

(B) Abolishing PA-MAP65-1 binding impaired the MAP65-1–alleviated cell death caused by NaCl. Wild-type and mutant MAP65-1 proteins were expressed in protoplasts before salt treatment for 3 h. Data are means ± sd from five replicates. An asterisk indicates that the mean value is significantly different from that of MAP65-1 (wild type) at P < 0.05.

(C) Microtubule cosedimentation assay using MAP65-1 (wild type) and MAP65-1 (mutant). Pellets and supernatants were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. W, MAP65-1 (wild type); M, MAP65-1 (mutant). P, pellets; S, supernatants.

(D) The MAP65-1 (mutant) protein did not bundle microtubules in vitro or in vivo. Microtubules were polymerized in a 1 μM tubulin solution with 2 μM MAP65-1 (wild-type or mutant protein). The rhodamine-labeled microtubules were visualized by confocal microscopy. Insets in right bottom, confocal images of wild-type and mutant MAP65-1-GFP overexpression in protoplasts, respectively. Bars = 10 µm.

(E) Turbidity of tubulin polymerization in the presence of MAP65-1 (wild type) and MAP65-1 (mutant).

We next examined whether the mutation in MAP65-1 is functionally important to salt tolerance. Protoplasts expressing the mutant MAP65-1 showed a higher level of cell death under salt stress than those expressing wild-type MAP65-1 (Figure 10B). Unexpectedly, this mutant MAP65-1 protein could not bind and bundle microtubules (Figures 10C and 10D) or increase the turbidity of the tubulin assembly (Figure 10E). When mutant MAP65-1-GFP was expressed in protoplasts, it could not bind to microtubules to form the array structures as wild-type MAP65-1-GFP (Figure 10D, insets in right bottom). It is possible that one or more of these eight residues is involved in MAP65-1 binding to microtubules. To address this question, proteins mutated at the M1, M2, and M4 locales, or simultaneously at the M1 and M2 locales, were tested for their microtubule binding capacity. The results showed that none of these mutations affected their microtubule binding activity (see Supplemental Figure 8 online). Therefore, the abolition of microtubule bundling required the simultaneous mutation of all eight residues; presumably, these combined mutations not only eliminated PA binding, but also affected the MAP65-1 tertiary conformation related to microtubule binding.

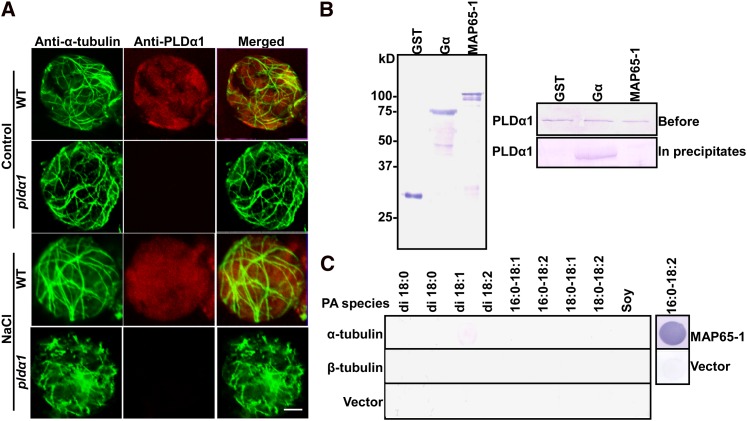

PLDα1 Does Not Bind to Microtubules or MAP65-1

To address whether the PLDα1 protein itself associates with and regulates microtubules, double immunofluorescence staining was performed using anti-α-tubulin and PLDα1 antibodies. In confocal observations, PLDα1 was detected in wild-type but not in pldα1 cells. No colocalization of PLDα1 and microtubules was observed (Figure 11A). Salt treatment induced slight microtubule depolymerization in wild-type cells and serious microtubule disruption in pldα1 cells but did not change localization between PLDα1 and microtubules (Figure 11A).

Figure 11.

PLDα1 and PA Do Not Bind to Microtubules

(A) Confocal images of double immunofluorescence staining of microtubules (green) and PLDα1 (red) in protoplasts. The images were taken 3 h after treatment with 25 mM NaCl. WT, the wild type. Bar = 20 μm.

(B) PLDα1 does not bind to MAP65-1. GST, GST-Gα, or GST-MAP65-1 was expressed in E. coli (left). PLDα1 with a His tag was incubated with GST, GST-Gα, or GST-MAP65-1, pulled down with glutathione agarose, and then subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-PLDα antibody (right).

(C) α- and β-tubulin proteins do not bind to PA. PA species (10 μg) were spotted onto nitrocellulose, followed by incubation with α- or β-tubulin protein solution. The interaction was detected by anti-α-tubulin or anti-β-tubulin antibody. An equal amount of MAP65-1 tagged with 6×His was used as the positive control, and an empty vector was used as the negative control.

To investigate whether PLDα1 interacted with MAP65-1, PLDα1 tagged with 6×His (Figure 11B) was incubated with a glutathione S-transferase (GST) vector, GST-MAP65-1, or GST-Gα (α subunit of G protein). As a positive control, PLDα1 was detected in beads containing GST-Gα (Zhao and Wang, 2004). No PLDα1 was coimmunoprecipitated with GST-MAP65-1 or GST vector (Figure 11B), suggesting that PLDα1 did not bind to MAP65-1 in vitro.

To determine if PA associated with α- or β-tubulin, different PA species were incubated with tubulins for protein-filter binding, followed by detection with anti-α- or anti-β-tubulin antibody, respectively. As shown in Figure 11C, compared with the interaction between PA and MAP65-1, none of the PA species bound to α- or β-tubulin. Taken together, these results indicate that PLDα1 does not bind to microtubules and that the interaction between PA and microtubules occurs via binding to MAP65-1.

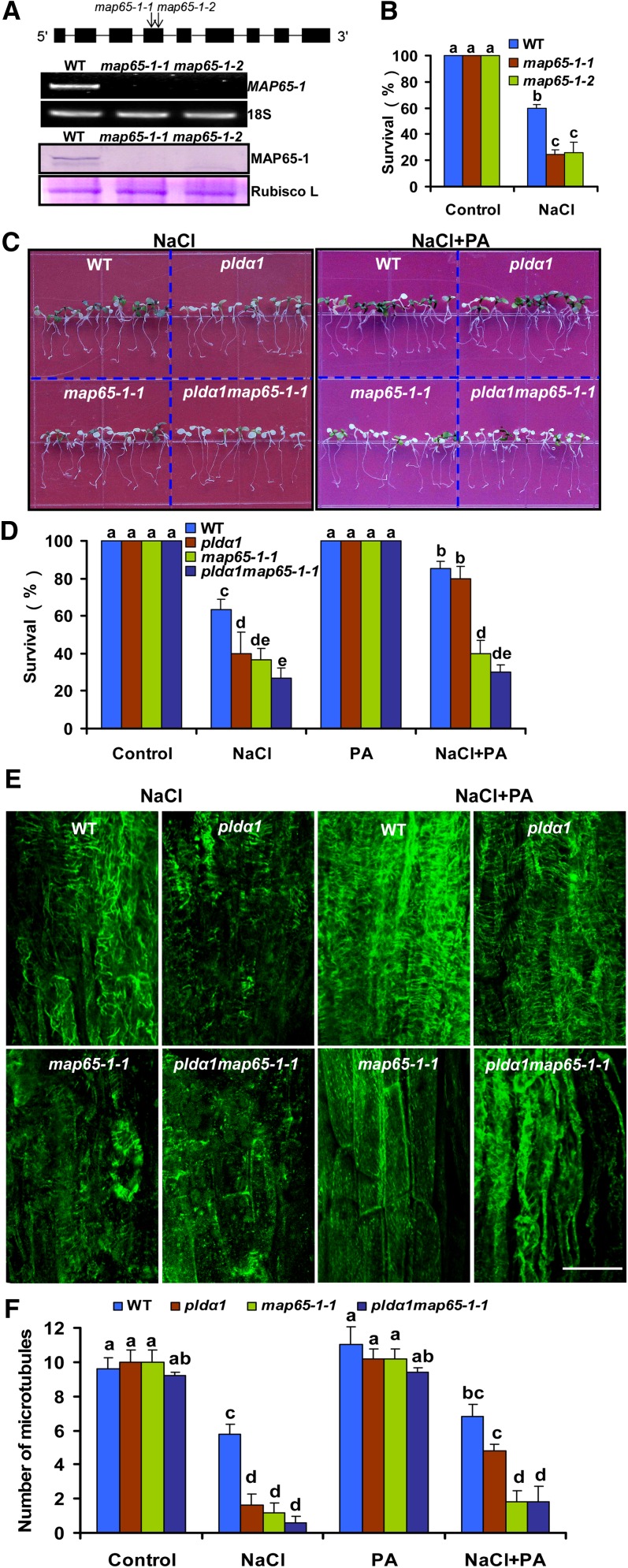

The pldα1map65-1 Double Mutant Shows Hypersensitivity to Salt Stress

The function of MAP65-1 in salt tolerance was investigated using two lines of T-DNA insertion mutants (map65-1-1, SALK_006083; map65-1-2, SALK_118225) after confirmation by RT-PCR and immunoblotting (Figure 12A). Prolonged salt treatments caused leaf chlorosis and bleaching, leading to plant death. More map65-1-1 and map65-1-2 seedlings died than did wild-type seedlings after exposure to 200 mM NaCl for 14 d (Figure 12B; see Supplemental Figure 9A online). In addition, knockout of MAP65-1 resulted in more microtubules being disrupted than in the wild type after seedlings were treated with NaCl or oryzalin (see Supplemental Figures 9B and 9C online). A pldα1 map65-1-1 double mutant was produced by crossing and confirmed by immunoblotting (see Supplemental Figure 10A online). The double mutant showed an additive salt-sensitive phenotype compared with pldα1 and map65-1-1 seedlings (Figures 12C and 12D). Pretreatment with 16:0-18:2 PA increased salt tolerance in pldα1, but not in map65-1-1 or pldα1 map65-1-1 mutants (Figures 12C and 12D); however, this did not affect the growth of either genotype in the absence of salt treatment (see Supplemental Figure 10B online).

Figure 12.

The pldα1 map65-1 Mutant Shows More Sensitivity to Salt Stress.

(A) Detection of the map65-1s mutant. Top panel: The gene structure of Arabidopsis MAP65-1. MAP65-1 contains nine exons and eight introns, which are represented by filled boxes and lines, respectively. Two arrows indicate the sites of T-DNA insertion in the MAP65-1 gene in map65-1-1 and map65-1-2 mutants. Middle panel: RT-PCR analysis of MAP65-1 gene expression in the wild type (WT), map65-1-1, and map65-1-2 mutants. The data are representative of three replicates with at least 10 seedlings used for each genotype each time. Bottom panel: An immunoblot of MAP65-1 using anti-MAP65-1 antibody. 18S rRNA and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (Rubisco L) were used as an internal control for RT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively.

(B) Survival ratio of the wild type, map65-1-1, and map65-1-2 after NaCl treatment. Seven-day-old seedlings were transferred to MS medium containing 200 mM NaCl. Photographs were taken 14 d after the transfer. Data are means ± sd from five replicates.

(C) Phenotypes of the wild type, pldα1, map65-1-1, and pldα1 map65-1-1 after NaCl treatment. Seven-day-old seedlings were transferred to MS medium containing 200 mM NaCl. Photographs were taken 14 d after the transfer. For PA treatment, the seedlings were grown in MS medium containing 20 μM 16:0-18:2 PA for 7 d before treatment with 200 mM NaCl.

(D) Survival ratio of wild type, pldα1, map65-1-1, and pldα1 map65-1-1 after the treatment indicated in (C). Data are means ± sd from five replicates.

(E) Confocal images of cortical microtubules in hypocotyl epidermal cells of the wild type, pldα1, map65-1-1, and pldα1 map65-1-1 by immunofluorescence labeling with anti-α-tubulin antibody. For PA treatment, the seedlings were grown in MS medium containing 20 μM 16:0-18:2 PA for 7 d before 50 mM NaCl treatment.

(F) Quantification of cortical microtubules of the wild type, pldα1, map65-1-1, and pldα1 map65-1-1 in hypocotyl epidermal cells as treated in (E). Confocal images for the control and PA treatment are shown in Supplemental Figure 10C online.

Columns with different letters in (B), (D), and (F) are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05).

To examine whether knockout of MAP65-1 affects microtubule organization under salt stress, we compared microtubule changes among the wild type, map65-1-1, and pldα1 map65-1-1 by immunofluorescence labeling. Microtubules of hypocotyl epidermal cells showed similar patterns in the wild type and three mutants (see Supplemental Figure 10C online). In pldα1 map65-1-1, almost no intact microtubules were found in NaCl-treated seedlings (Figure 12E). However, pretreatment with PA alleviated the sensitivity of microtubules to NaCl in pldα1 but not in map65-1-1 or pldα1 map65-1-1 (Figures 12E and 12F). These genetic results suggest that the PA–MAP65-1 interaction plays an essential role in stabilizing microtubules and salt tolerance in plants.

DISCUSSION

Microtubules anchored to the plasma membrane constitute the majority of the plant interphase arrays (Ehrhardt and Shaw, 2006; Hashimoto and Kato, 2006; Paredez et al., 2006; Beck et al., 2010). The cortical microtubule arrays respond to diverse developmental and extracellular stimuli, including plant hormones and biotic and abiotic stresses (Ehrhardt and Shaw, 2006). Physical linkages between microtubules and the membrane were recently observed using high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (Barton et al., 2008). Only a few candidate proteins have been proposed as potential linkers between the plasma membrane and microtubules, for example, PLD (Gardiner et al., 2001) and the membrane-integrated formin (At-FH4) (Deeks et al., 2010). However, it is still unclear how these proteins act as linkers and what their functions are. In this study, we demonstrated that lipid PA acts as a linker between the plasma membrane and microtubules via MAP65-1, which is essential for salt stress signaling in Arabidopsis.

Lipid Signaling Is Essential for Microtubule Organization under Salt Stress

Salt stress affects microtubule organization. The cytosolic salt imbalance caused by insufficient Na+/H+ antiport activity results in microtubule depolymerization and salt sensitivity in the sos1 mutant (Zhu, 2003; Shoji et al., 2006). The loss of functional PFD3 and PFD5, which are involved in microtubule biogenesis, leads to fewer and disorganized microtubules, as well as hypersensitivity to salt (Rodríguez-Milla and Salinas, 2009). These results suggest an essential role of microtubule stabilization in plant tolerance to salt. On the other hand, artificial stabilization of microtubules with paclitaxel increases seedling death under salt stress, suggesting that early microtubule depolymerization is an important step in the salt stress response (Wang et al., 2007). Microtubule depolymerization is probably caused by SPR1 degradation regulated by the 26S proteosome (Wang et al., 2011) and is followed by the formation of new microtubule networks, which are essential for seedling survival under salt stress (Wang et al., 2007). During the initial microtubule depolymerization, Ca2+ channel opening and Ca2+ increase is a possible cue (Wang et al., 2007; see Supplemental Figure 4B online). Therefore, microtubule arrays are expected to be organized and controlled temporally in plant cells in response to salt stress.

The question arises of how microtubule polymerization-depolymerization dynamics are precisely controlled under salt stress. NaCl itself cannot be a regulator because polymerization of purified bovine tubulin in vitro is not inhibited by NaCl at concentrations as high as 400 mM (Shoji et al., 2006). SOS1, a transmembrane protein with a long cytoplasmic tail, has also been ruled out by site mutation experiments (Shoji et al., 2006).

Results from this study suggest that PLDα1 is involved in the regulation of microtubule organization under salt stress. PLDα1 was activated when seedlings or cells were challenged with NaCl (Yu et al., 2010; Figure 7B; see Supplemental Figure 11A online). The entry of NaCl into cells could activate PLDα1 directly, as this activity was stimulated by in vitro NaCl treatment as low as 0.1 mM (see Supplemental Figure 11B online). Early work also demonstrated that total PLD activity in tobacco cells was activated by salt (Dhonukshe et al., 2003). Ca2+ can act as an activator of PLDα by binding to the C2 domain (Wang et al., 2006). Microtubule depolymerization is known to be a cause for Ca2+ entry into the cytosol by increasing Ca2+ channel activity (Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011). PLD activation is important for microtubule organization, as loss of PLDα1 resulted in serious microtubule disorganization under salt stress. The depolymerized tubulins inhibited PLD activity in vitro (see Supplemental Figure 12 online). This inhibition of PLD activity by tubulins seems to conflict with the fact that oryzalin, which induces microtubule depolymerization, stimulates PLD activity in seedlings (see Supplemental Figure 4A online). This discrepancy is probably due to the fact that different substances (natural tubulins versus chemical oryzalin) and environments (in vivo versus in vitro) were used in these experiments. Oryzalin (and salt stress) did induce microtubule depolymerization but also induced other physiological processes, such as Ca2+ increase in the cytosol (see Supplemental Figure 4B online; see also Supplemental Methods 1 and Supplemental References 1 online). The activation of PLDα by oryzalin was inhibited by Ca2+ channel inhibitor (see Supplemental Figure 4A online), suggesting that oryzalin’s effects are the result of combined physiological processes, which do not exist in the in vitro environments used for tubulin treatment.

In Arabidopsis, PLDα and PLDδ are the most abundant PLDs. The ablation of PLDα1 or PLDδ did not affect the levels of α- or β-tubulin, even under salt stress (see Supplemental Figure 13 online). Gardiner et al. (2001) characterized a 90-kD protein in tobacco as a MAP that appears to be identical to PLDδ in Arabidopsis. However, our work here showed that PLDδ was not activated by salt treatment (see Supplemental Figures 11C and 11D online). In addition, microtubule organization and density under salt stress (or oryzalin treatment) was not affected by knockout of the PLDδ gene (see Supplemental Figures 14B, 14C, and 14E to 14G online). These observations suggest that specifically PLDα1 may be involved in the salt stress response. In early work, Katagiri et al. (2001) found that both dehydration and high salt stress increased PLDδ mRNA accumulation. Antisense silencing of PLDδ led to lower PA accumulation induced by dehydration, but it is still unclear if PLDδ regulates salt tolerance in plants. The results of this work showed that knockout of PLDδ did not affect seedling survival under salt stress conditions compared with the wild type (see Supplemental Figure 14D online). The inconsistency of PLDδ mRNA accumulation and salt tolerance could be due to posttranscriptional regulation of this protein during the stress. At present, however, we cannot exclude the possibility that PLDδ functions in an unknown manner during the salt response. For example, double mutants of PLDα1 and PLDδ are more sensitive to salt than are single mutants according to root growth, suggesting PLDα and PLDδ may interact directly or indirectly in response to salt stress (Bargmann et al., 2009). The cooperation between PLDα1 and PLDδ through glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases has been found in abscisic acid–induced stomatal closuring (Guo et al., 2012).

PA, the product of PLDα, is a key regulator of microtubule polymerization. We showed that genetic and pharmacological inhibition of PA generation results in microtubule depolymerization, which is consistent with results in tobacco cells (Dhonukshe et al., 2003) and algae (Peters et al., 2007). In leek (Allium porrum) leaves, 1-butanol converts microtubules from the transverse to longitudinal orientation, presumably by promoting microtubule detachment from the membrane (Sainsbury et al., 2008). In tobacco cells, the cortical microtubules are released from the plasma membrane and depolymerized in the presence of 1-butanol and are restored to normal patterns after 1-butanol is removed (Dhonukshe et al., 2003). By contrast, exogenous PA recovered NaCl-disrupted microtubule arrays in plda1, in which the PA level was much lower than that in wild-type cells. In addition, our TEM observations revealed that the lack of NaCl-induced production of PA in pldα1 resulted in less frequent association of microtubules with the plasma membrane, which might in turn lead to membrane damage and cell death caused by salt treatment. Taking these results together, we conclude that PLDα1-derived PA is essential for the regulation of microtubule organization under salt stress.

PA and MAP65-1 Interaction Modulates Microtubule Organization and Salt Tolerance

PA enhances the polymerization of the actin cytoskeleton in pollen tubes (Huang et al., 2006). PA binds to a capping protein and dissociates it from the barbed ends of the actin filament, promoting the addition of a profilin-actin complex onto the barbed ends, resulting in filament elongation (Huang et al., 2003, 2006). More recently, genetic evidence shows that the capping protein acts as a PA biosensor to transduce lipid signaling into changes in actin cytoskeleton dynamics (Li et al., 2012). In this study, we demonstrated that PA promotes microtubule organization in a different way. It regulates microtubule bundling and polymerization together with MAP65-1. Moreover, the interaction between PA andMAP65-1 is important for salt tolerance.

PA itself could not bind or bundle microtubules. It could not mitigate the microtubule disruption caused by salt in the map65-1 mutant, suggesting that MAP65-1 is necessary for PA-mediated stabilization of microtubules. It has been reported that MAP65-1 stabilizes microtubules against various destabilizing agents (Van Damme et al., 2004a). Our experimental results show that MAP65-1 is involved in salt tolerance by stabilizing microtubules. Salt stress reduced MAP65-1 binding to microtubules, and knockout of MAP65-1 resulted in microtubule depolymerization under salt stress. Furthermore, knockout of MAP65-1 or disruption of the MAP65-1 association with microtubules led to salt hypersensitivity. These results indicate that MAP65-1 positively regulates salt tolerance via microtubules. Moreover, overexpression of MAP65-1 increased salt tolerance in Arabidopsis cells, supporting this notion. The increase in salt tolerance following overexpression of MAP65-1 was more obvious in wild-type cells than in pldα1 cells, suggesting that PLDα1/PA is essential to MAP65-1 promotion of salt tolerance. Genetic evidence also indicates that double knockout of PLDα1 and MAP65-1 caused an additive salt sensitivity, compared with either single mutant. However, PLDα1 itself did not bind to MAP65-1. Low salt tolerance in pldα1 cells was related to its low PA level (Yu et al., 2010), and the addition of PA improved salt tolerance in pldα1 cells overexpressing MAP65-1. Taken together, the data all point to the conclusion that mutual regulation of PA and MAP65-1 is required for resistance to salt stress by stabilization of microtubules.

The importance of the PA-MAP65-1 interaction in salt tolerance was proved by mutagenesis of eight amino acids in MAP65-1, which resulted in the loss of its activity in PA binding and promotion of salt tolerance. The essentiality of these amino acids for PA binding was examined by another mutagenesis (i.e., mutation of MAP65-6 [weak PA binding] to the same amino acids as MAP65-1 in corresponding sites led to an increase in PA binding). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the mutation in MAP65-1 alters the three-dimensional structure of the protein, disrupting its ability to bind PA. Mutation of the eight amino acids in MAP65-1 reduced its activity in microtubule bundling, suggesting possible changes in tertiary conformation. On the other hand, these results also imply that, in vivo, PA binding to these amino acids may increase the intensity of MAP65-1 association with microtubules by altering the protein conformation. It is necessary to further detail the structural mechanisms of PA and MAP65-1 interaction in the salt response.

Nine MAP65s have specific localizations and different roles in cell development in Arabidopsis (Smertenko et al., 2004, 2006, 2008; Van Damme et al., 2004b; Mao et al., 2005). A MAP can show different activity in microtubule bundling after a posttranslational modification of the protein during the cell cycle (Ho et al., 2012). Neither MAP65-6 nor MAP65-8 could regulate microtubule polymerization, regardless of the presence or absence of PA. On the other hand, accumulation of another MAP, SPR1, causes salt stress hypersensitivity (Wang et al., 2011). These results imply that these MAPs may regulate different steps in the salt response; for example, SPR1 may regulate microtubule depolymerization and MAP65-1 microtubule polymerization. Both processes are essential for plant tolerance to salt stress. Thus, our data, together with those of others, demonstrate the specificity and importance of the interaction between PA and MAP65-1 for cortical microtubule stabilization in the salt stress response.

The Interaction between PA and MAP65-1 Reveals a Regulatory Mechanism for MAPs

MAP65-1 is phosphorylated by MAPKs, especially MPK4 and MPK6 (Smertenko et al., 2006; Beck et al., 2010), their putative orthologs NRK1/NTF6 (Sasabe et al., 2006), and cyclin-dependent protein kinase (Mao et al., 2005). The phosphorylation of MAP65-1 reduces its microtubule-bundling activity and enhances destabilization and turnover of microtubules at the phragmoplast equator, thereby promoting mitosis (Sasabe et al., 2006; Smertenko et al., 2006). Genetic evidence has shown that a deficiency of MAPK kinase kinases (ANP2/ANP3) induces a lesser phosphorylation status of MAP65-1, heavy bundling of microtubules, and abnormal cell growth patterns, suggesting that ANP2/ANP3 affects microtubule organization via MAP65-1 (Beck et al., 2010). More recently, a MAPK kinase (MKK6) was identified as a linker between MAPK kinase kinase and MAPK during cytokinesis (Kosetsu et al., 2010), although this MAPK kinase has yet to be tested for the regulation of MAPs and microtubules. These results emphasize the importance of both microtubule assembly and dynamics regulated by the coordinated action of microtubule-MAPs and MAPK signaling during cytokinesis and cell growth.

Under salt stress, however, a reduction in cell elongation and division is one strategy by which plants may survive (Munns and Tester, 2008). DELLA proteins, which are negative regulators of growth, integrate salt-activated ethylene and ABA signaling to restrain cell proliferation and expansion that drive plant growth (Achard et al., 2006). This enhanced growth repression is distinct from passive growth rate reduction caused by salt-induced perturbation of the physiological processes that drive growth. Instead, the growth restraint conferred by DELLA proteins may enable a redirection of resources to support mechanisms that promote survival under adversity and decrease water consumption and toxic Na+ absorption, thereby promoting salt tolerance (Achard et al., 2006; Munns and Tester, 2008). The stabilization of microtubules not only constrains the cell volume but also promotes stability of the cell structure under stress, providing a measure of guarantee for vital processes. A nonprotein regulator of MAP65-1 identified in this work, the lipid PA, promotes MAP65-1 activity in microtubule polymerization and bundling, which is vital for plants to survive under salt stress. It is plausible that microtubule polymerization and depolymerization is changeable, dependent on developmental and environmental signals.

PA regulation of MAP65-1 is different from the regulation by MAPK cascades discussed above. The identified domains in MAP65s include microtubule binding domains and phosphorylated domains (Sasabe et al., 2006; Smertenko et al., 2006, 2008). In Arabidopsis MAP65s, microtubule binding domains contain two regions, MTB1 and MTB2, distal and proximal, respectively, to the C terminus (Smertenko et al., 2008). In MAP65-1, MTB2 harbors the phosphorylation sites (residues 495 to 587) that control its activity (Smertenko et al., 2006, 2008). In tobacco MAP65-1, Thr-579 has been identified as a site that is phosphorylated by NRK1/NTF6 MAPK (Sasabe et al., 2006). The PA binding regions in MAP65-1 identified in this study (residues 1 to 150 and 340 to 494) are different from the microtubule binding or phosphorylated regions. This suggests that the structural base for PA regulation of MAP65-1 is different from that for MAPK cascades.

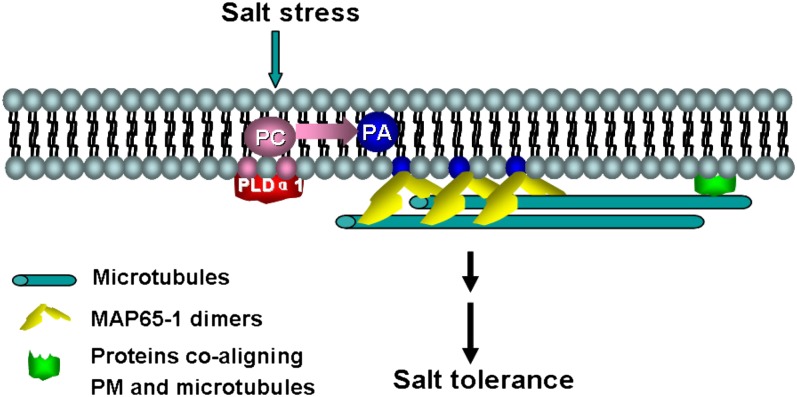

In conclusion, we propose a model for PLD/PA interaction with microtubules in response to salt stress. In this model, NaCl stimulates PLDα1 activity directly or by other signaling pathways (for example, Ca2+ signaling), leading to a local increase in PA concentration in the plasma membrane. PA binds to MAP65-1, enhances its activity in microtubule polymerization and bundling, and consequently results in better survival under salt stress (Figure 13). Some questions remain be addressed in future studies, such as whether PA affects the polarity of microtubules in the MA65-1–induced bundles and if PA regulates MAPs and microtubules via other signal pathways in response to salt stress.

Figure 13.

Schematic Illustration of the Interaction between PA and MAP65-1 in Response to Salt Stress.

PLDα1 is activated by salt stress signaling to produce PA, which binds to MAP65-1. The interaction between PA and MAP65-1 strengthens the stability of microtubules to promote salt tolerance. PM, plasma membrane.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) seeds were germinated in MS medium (2% sugar and 1% agar) at 4°C for 2 d and then grown in a growth room at a light intensity of 160 μmol m−2s−1 and a day/night regime of 14 h/10 h (24°C/21°C). Protoplasts were isolated from the leaves of 4- to 6-week-old plants.

The pldα1 mutant was reported previously (Zhang et al., 2009). The map65-1 and pldδ mutants were obtained from ABRC at Ohio State University. The homozygous map65-1-1 and map65-1-2 lines were confirmed by a PCR-based approach and immunoblotting. Primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) were designed using the SALK T-DNA verification primer design program (signal.salk.edu/tdnaprimers.2.html): MAP65-1-RT-L/MAP65-1-RT-R and left border primer LB3.1. The 18S rRNA was used as an internal control, with primers 18S-RT-L/18S-RT-R pld(delta) mutant information and its confirmation is shown in Supplemental Methods 1 and Supplemental References 1 online. The pld mutants (pldα1 and pldδ) were crossed with transgenic Arabidopsis expressing GFP-tagged α-tubulin (35S:GFP-TUA6) for the observation of cortical microtubules. The homozygous pldα1 map65-1 double mutant was confirmed both by PCR and immunoblotting.

Salt Treatment and Microtubule Observation

Both wild-type and pldα1 (pldδ) seedlings expressing 35S:GFP-TUA6 were grown on MS medium for 7 d and then transferred to MS medium with 50 mM NaCl. After the indicated treatment, the cortical microtubules in cotyledons and hypocotyls of both genotypes were observed under a confocal microscope (TCS SP2; Leica) with an excitation at 488 nm and emission at 535 nm. For the microtubule recovery experiments, after pretreatment with 50 mM NaCl for 2 d, the seedlings of both genotypes were transferred to MS medium without NaCl for another 2 d before the microscopy.

Seedling Survival Assay

To investigate the roles of PLDs and MAP65-1 and their interactions in salt tolerance, 7-d-old seedlings of the wild type, pldα1, pldδ, map65-1-1 (and map65-1-2), and pldα1map65-1-1, none of which contained 35S:GFP-TUA6, were exposed to 200 mM NaCl for 14 d. Seedling survival was measured in at least 30 seedlings of each genotype with three replicates.

RNA Isolation, Gene Cloning, and Vector Construction

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis plants by the TRIzol method, and reverse transcription was performed using 5 micrograms total RNA and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCR amplifications were performed according to standard protocols in thermocyclers using Taq DNA polymerase or Pyrobest DNA polymerase (TaKaRa).

MAP65-1, MAP65-5, MAP65-6, and MAP65-8 were cloned from Arabidopsis cDNA by PCR. The primers for cloning were MAP65-1-FL-L/MAP65-1-FL-R, His-MAP65-5-L/His-MAP65-5-R, His-MAP65-6-L/His-MAP65-6-R, and His-MAP65-8-L/His-MAP65-8-R, respectively. The PCR products were first cloned into a Promega pGEM-T Easy Vector according to the kit’s instructions and were then verified by sequencing. The four cDNAs of MAP65s were introduced into the pET28a vector (Novagen) between the BamHI and SalI sites. Fusion proteins with His tags at the N and C termini were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3; Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The MAP65-1 fragments were amplified by PCR using MAP65-1 cDNA as a template. The primers MAP65-1-FL-L/-R, MAP65-1-FL-L/MAP65-1-a-R, MAP65-1-FL-L/MAP65-1-b-R, MAP65-1-c-L/-R, and MAP65-1-d-L/MAP65-1-FL-R were for MAP65-1 (full length), MAP65-1 (amino acids 1 to 150), MAP65-1 (amino acids 1 to 339), MAP65-1 (amino acids 340 to 494), and MAP65-1 (amino acids 495 to 587), respectively. The cDNAs of these MAP65-1 fragments were constructed into the vector pGEX-4T (Amersham Biosciences). MAP65-6 and MAP65-8 were introduced into pGEX-4T using primers GST-MAP65-6-F/R and GST-MAP65-8-F/-R.

To characterize PA binding sites in MAP65-1, the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to generate the site-directed mutants. Using MAP65-1 cDNA as the template, the primers for M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5 mutations were 65-1-M1-F/65-1-M1-R, 65-1-M2-F/65-1-M2-R, 65-1-M3-F/65-1-M3-R, 65-1-M4-F/65-1-M4-R, and 65-1-M5-F/65-1-M5-R, respectively. The primers 65-6-M1-F/65-6-M1-F, 65-6-M1-F/65-6-M1-F, and 65-6-M1-F/65-6-M1-F were used for the MAP65-6 mutations.

To determine the function of MAP65-1 in salt tolerance in cells, MAP65-1 with a HA tag fused to the C terminus was transiently expressed in protoplasts under control of the 35S promoter (Zhang et al., 2004). The primers for MAP65-1-HA and MAP65-1-GFP were MAP65-1-HA-L/-R and MAP65-1-GFP-L/-R, respectively.

For immunoprecipitation experiments, PLDα1 cDNA was first cloned into pBluescript SK (Zhao and Wang, 2004) using primers His-PLDα1-L/-R and was then introduced into the pET28a vector between the BamHI and SalI sites. The Gα cDNA obtained from ABRC at Ohio State University was fused into pGEX-4T between the EcoRI and XhoI sites using primers GST-Gα-L/-R. PLDδ cDNA was cloned from Arabidopsis leaves and constructed into pGEX-4T using PLDδ-L/-R primers.

The sequences of all of the primers used in this article are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Assay of Lipid-Protein Binding

The binding of MAP65s, truncated MAP65-1, and mutant MAP65-1 (M1, M2, and M4 combined mutations) to lipids was performed using nitrocellulose filters, liposome binding, and ELISA approaches, as described previously (Zhang et al., 2009).

Microtubule Polymerization and Observation

Porcine brain tubulins were purified according to previously published methods (Castoldi and Popov, 2003).

For the microtubule polymerization assay, MAP65-1 at a concentration of 2 μM plus 16:0-18:2 PA was added to a 30 μM tubulin solution in PME buffer (100 mM PIPES-KOH, pH 6.9, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA) containing 1 mM GTP. MAP65-1 and PA alone or MAP65-1 plus 16:0-18:2 PC were used as controls. Turbidimetric analysis was used to monitor microtubule polymerization by measuring the absorbance at 350 nm and at 37°C using a spectrophotometer (TECAN Infinite M200 multifunctional microplate reader).

For microtubule observation, rhodamine-labeled tubulin was polymerized in PME buffer containing 1 mM GTP in the presence or absence of 5 μM MAP65-1 plus PA (or PC) at 37°C for 30 min. Then, the samples were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde for observation by confocal microscopy.

Cosedimentation Assay

An analysis of the cosedimentation of the fusion proteins with microtubules was performed according to previously published protocols (Mao et al., 2005). The purified proteins were centrifuged at 200,000g at 4°C for 20 min before use. After polymerization and stabilization with paclitaxel, 5 μM microtubules was incubated with PMEP buffer (PME plus 20 μM paclitaxel) containing MAP65-1 fusion protein at a concentration of 0 or 2 μM plus 16:0-18:2 PA, di18:0 PA, or PC, respectively, at room temperature for 20 min. After centrifugation at 100,000g for 20 min, the supernatant and pellets were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The amount of fusion protein bound to the microtubules was determined by gel scanning, and the binding ratio was analyzed with an Alpha Image 2200 documentation and analysis system.

For the lipid-MAP65 and lipid-MAP65 microtubule interaction assay, phospholipids were sonicated in PME buffer and added to reaction buffer for 30 min before cosedimentation experiments.

To detect PA bound to MAP65-1, lipid vesicles including 10 µM NBD-PA and 5 µM PC were sonicated in PME buffer, followed by centrifugation at 40,000g. The supernatants were incubated with 2 µM paclitaxel-stabilized microtubules with or without MAP65-1 for 30 min at room temperature. The mixtures were then centrifuged at 20,000g to precipitate the microtubules, and the NBD-PA bound to MAP65-1 was quantified by fluorescence spectrophotometry. Lipid vesicles composed of 10 µM NBD-PC and 5 µM PC were used as negative controls.

Pull-Down Experiments

The expression and purification of His-PLDα1 and GST-Gα proteins and the pull-down experiments were performed as described previously (Zhao and Wang, 2004). For cosedimentation of PLDα1 with MAP65-1, the coprecipitation buffer contained 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2, and protease inhibitors (5 µg each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and antipain). Purified GST-MAP65-1-agarose beads were incubated with bacterially expressed PLDα1 with His tag in the coprecipitation buffer for 3 h at 4°C, and the beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed three times with the coprecipitation buffer containing 0.01% Triton X-100.

The proteins in the beads were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PLDα antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by the secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. Proteins were quantified by the Bradford method using the reagent from Bio-Rad.

Protoplast Isolation, Transient Expression of MAP65-1, and Calculation of Cell Survival

Mesophyll protoplasts were isolated from Arabidopsis leaves, followed by transfection with MAP65-1-HA (wild-type or mutant MAP65-1), according to procedures described previously (Zhang et al., 2004). To test the MAP65-1 protein level in protoplasts, equal amounts of total protein from protoplast lysates were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride filters. The filters were blotted with anti-HA antibody and then incubated with a second antibody conjugated to an alkaline phosphatase. MAP65-1-HA proteins were detected by staining for phosphatase activity.