Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To explore the experience of living with a cancer diagnosis within the context of a pre-existing functional disability and to identify strategies to promote health in this growing population of cancer survivors.

Research Approach

Qualitative descriptive

Setting

Four sites in the United States

Participants

19 female cancer survivors with pre-existing disabling conditions

Methodologic Approach

Four focus groups were conducted. The audiotapes were transcribed and analyzed using content analysis techniques.

Main Research Variables

cancer survivor, disability, health promotion

Findings

Analytic categories included living with a cancer diagnosis, health promotion strategies, and wellness program development for survivors with pre-existing functional limitations. Participants described many challenges associated with managing a cancer diagnosis on top of living with a chronic disabling functional limitation. They identified strategies they used to maintain their health and topics to be included in health promotion programs tailored for this unique group of cancer survivors.

Conclusions

The “double whammy” of a cancer diagnosis for persons with pre-existing functional limitations requires modification of health promotion strategies and programs to promote wellness in this group of cancer survivors.

Interpretation

Nurses and other health care providers must attend to patients’ pre-existing conditions as well as the challenges of the physical, emotional, social, and economic sequelae of a cancer diagnosis.

Keywords: cancer, functional disability, health promotion, survivor

Over 47 million Americans have one or more disabilities, a number projected to increase over the next 20 years (Brault, 2008). Similarly, the incidence of cancer in the U.S. will continue to rise, resulting in an 81% increase in cancer survivors by 2020 (Levit, Smith, Benz, & Ferrell, 2010). The intersection of multiple co-morbidities in this aging population will require a health care work force well-versed in managing complex care needs and health promotion strategies that maximize quality of life.

As an underserved population, persons with disabilities experience health disparities. They are more likely than non-disabled persons to experience delays in obtaining health care, receive fewer cancer screening exams and tests, use tobacco, be overweight, and experience psychological distress (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Further, this group may be less likely to receive standard cancer care, such as less breast-conserving surgery or radiation for breast cancer, and experience higher cancer-related rates of mortality (Chirikos, Roetzheim, McCarthy, & Iezzoni, 2008; Iezzoni et al., 2008a, 2008b; McCarthy et al., 2007). Reasons for these disparities are complex and may include problems with physical access to care, poor quality of cancer screening services, delay in treatment, and other medical considerations that impact treatment choices (Drainoni et al., 2006; Iezzoni et al., 2008a; Liu & Clark, 2008).

Cancer survivorship studies reveal challenges faced by short- and long-term survivors. Although many long-term survivors indicate that they are in good health, others live with numerous sequelae of the disease and treatment: pain, fatigue, peripheral neuropathies, lymphedema, gastrointestinal problems, sleep disturbances, bladder dysfunction, and menopause (Brearley et al., 2011; Harrison et al., 2011). At one year post-diagnosis, people with one or more comorbid conditions have a higher symptom burden than those with none (Shi et al., 2011). Some survivors experience psychosocial concerns: fear of recurrence, sexual problems, depression, problems with social relationships, and loneliness (Foster, Wright, Hill, Hopkinson, & Roffe, 2009; Harrison et al., 2011; Rosedale, M., 2009). Survivors are also more likely to experience work disability than individuals without cancer history (Short, Vasey, & Belue, 2008), and may face diminished employment opportunities, difficulty obtaining health and life insurance, and high out-of-pocket costs for health care (Hewitt & Ganz, 2006).

Although we have some understanding of health issues among cancer survivors and persons with disabilities, little is known about the needs of persons who have a pre-existing functional disability who then develop a cancer diagnosis and undergo treatment. These survivors seem to be absent from cancer survivor studies because demographic profiles do not typically specify functional disability as a pre-existing condition. Studies suggest that the challenges associated with living with a functional disability could uniquely impact the cancer experience and subsequent health promotion needs and services for this growing population. For example, women with mobility impairments who are breast cancer survivors may experience physical access barriers to care such as difficulties with imaging equipment and procedures and transferring to exam tables (Iezzoni, Kilbridge, & Park, 2010). Further, in a recent study of predictors of quality of life for long-term cancer survivors with preexisting disabling conditions, Becker, Kang, and Stuifbergen (2012) found that participants had poorer physical well-being than survivors without such preexisting conditions.

Despite the challenges associated with cancer survivorship, health promotion activities can positively impact survivors by improving quality of life, psychological function, and fatigue (Alfano et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2011; Conn, Hafdahl, Porock, McDaniel, & Nielsen, 2006; Groff et al., 2009; Harding, 2012). Similarly, wellness interventions tailored to persons with chronic and disabling conditions can positively impact health (Stuifbergen, Morris, Jung, Pierini, & Morgan, 2010). However, little is known about the experience of cancer survivorship in persons with pre-existing functional disabilities or how to best tailor health promotion interventions to meet their needs. Hence, the purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to

-

■

explore the experience of living with a cancer diagnosis within the context of a pre-existing functional disability;

-

■

identify strategies these individuals use to promote health; and

-

■

identify topics to be included in a wellness intervention program tailored to this group of cancer survivors.

This study defined functional disability broadly, using the operational definition from Federal surveillance studies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005): “Are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems”. The conceptual orientation was based on an explanatory model of health promotion and quality of life in chronic disabling conditions (Stuifbergen, Seraphine, Harrison, & Adachi, 2005; Stuifbergen, Becker, Rogers, Timmerman, & Kullberg, 1999). The model suggests that quality of life in disabled persons results from a complex interaction between illness severity, antecedent factors such as resources, barriers, social support, and self efficacy, and health-promoting behaviors.

Methods

Data were collected as part of a study of health promotion for cancer survivors with pre-existing disabling conditions. The study began with a nationwide survey of factors predicting health-promoting behaviors and quality of life among cancer survivors who had completed active treatment. As described elsewhere, 145 adult cancer survivors with chronic and disabling conditions prior to their cancer diagnosis and treatment completed surveys by mail (Becker et al., 2012). In the study’s second phase, focus group participants were recruited to discuss their experience with living with a cancer diagnosis within the context of a pre-existing functional disability, and provided information that could be used to adapt a wellness intervention for people with disabilities to the needs of cancer survivors with other prior disabling conditions.

Focus group methodology was chosen to capitalize on the richness that can come from a group’s discussion of complex health issues. The focus groups were held in Chicago, Villanova, Pennsylvania, Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Austin, Texas. Three disability research programs assisted in the organization of focus groups in their respective communities. The fourth focus group was organized by the researchers in their own community. Following Institutional Review Board approval, participants were recruited by the local staff of disability research programs and via the researchers’ contacts with individuals who participated in the study’s earlier survey phase. A flier describing the focus group study and the inclusion criteria was given to all participating research projects. Participant inclusion criteria included a self-reported cancer diagnosis and a functional disability prior to the cancer diagnosis, the completion of active treatment, an ability to speak English, and an age of at least 21 years. Given the study’s qualitative approach and focus group format, we recruited a convenience sample of 19 participants split between the 4 groups. The sample size was based on the number of participants who could be recruited at each study site; no participants dropped out of the study. Participants received a $75 money order for participating.

Procedure

All focus groups were held in locations convenient to people with disabilities in their respective communities. Three were held in universities/medical centers; the fourth was held in a local independent living center. Because transportation can be a barrier to participation in research for people with functional limitations, transportation reimbursement was also offered.

The second author, an experienced focus group moderator, developed the focus group guide and conducted three of the focus groups. The fourth author, also an experienced focus group moderator, was trained by the second author and conducted the fourth group. Homogeneity of moderation was ensured by using identical interview questions and by reviewing the transcribed group discussions for consistency with the interview process and questions. All focus groups met once, were tape-recorded, and lasted from 60 to 90 minutes. In addition, assistant moderators were recruited at the local sites to take field notes and to assist the moderator with meeting logistics. Two participants who had sensory impairments (visual and hearing) participated with the assistance of accommodations that included large print for written materials and auditory implants that magnified sound. Focus group participants completed a brief background survey that provided demographic information, type of cancer diagnosis, stage of cancer, type of treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, radiation, surgery), degree of assistance needed, and time since diagnosis and completion of active treatment. The focus group interview questions were developed by Stuifbergen, Harrison, Becker, and Carter (2004) for a study that refined a similar wellness intervention for persons with chronic and disabling conditions. The sessions were modified slightly to make them specific to cancer survivorship. At each focus group session, the moderator welcomed the participants and obtained informed consents. She then reviewed the focus group procedures with them. The sessions began with an ice-breaking question: “How long have you been a cancer survivor?” The moderator then moved to these questions:

What is it like to live with cancer and a pre-existing functional limitation?

What do you do to take care of your health?

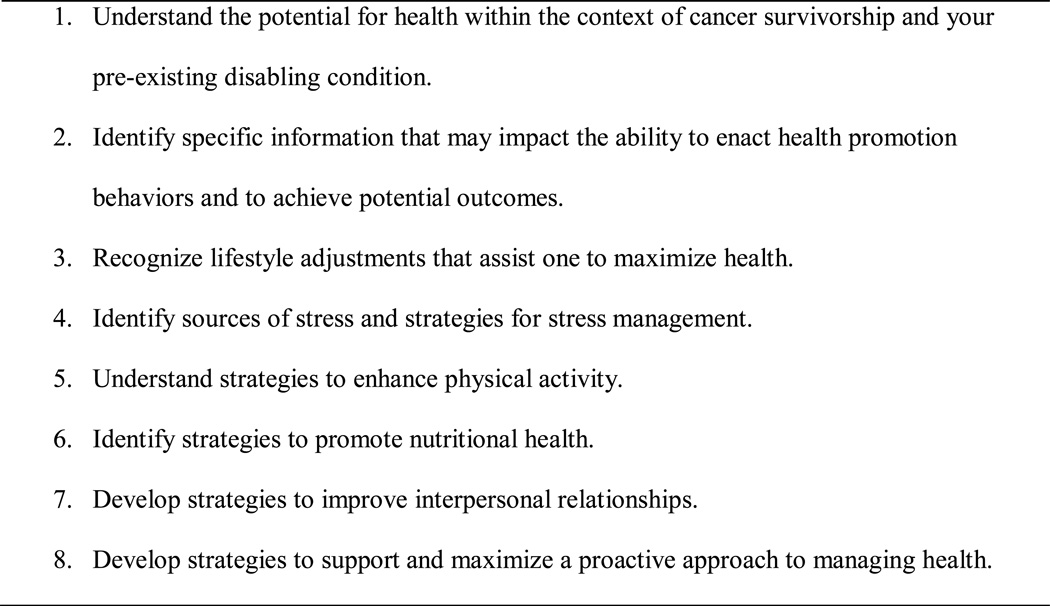

The moderator then asked the participants to consider a list of topics covered in the wellness intervention originally designed by Stuifbergen et al. (1999) (see Figure 1). Participants were asked whether these topics addressed important issues for cancer survivors like themselves. They were asked whether other topics should be included, and what the most important topics for cancer survivors with disabilities might be. At the session’s end, participants received survivorship information about local resources and a link to the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship’s survivor toolkit, as well as a $75 money order.

Figure 1.

Wellness Program Topics

Data Analysis

A research assistant transcribed tape recordings from three of the four focus groups. The fourth tape could not be transcribed, because of equipment failure. However, the moderators’ notes plus the notes from two note-takers remained available for analysis. The moderators compared the transcriptions with their notes to check for accuracy. Data were analyzed inductively using Patton’s (2002) qualitative content analysis procedures. The interview transcripts were reviewed line by line for significant phrases and statements. These data chunks were coded with tentative labels and combined into like groupings to form core categories of information that addressed the three study aims. To promote the findings’ trustworthiness, the first author independently analyzed the data and met with the second author to discuss coding results, preliminary analytic categories, and tentative findings, and to finalize the results. Any differences between the two authors’ interpretation of the data were resolved by re-reviewing the focus group transcriptions and creating a shared understanding of the issue in question. The results were also compared with written responses to open-ended questions and other comments on the 145 mailed surveys; these responses were consistent with the focus group data. Because 11 focus group participants also participated in the mailed survey, their survey comments were not included in this comparison.

Results

Study participants were predominantly non-Hispanic, white, well-educated older women (see Table 1). Although the study was not limited to women, no men volunteered to participate. The participants’ pre-existing functional disabilities were mainly neuromuscular or orthopedic, including multiple sclerosis, spinal cord impairment, arthritis, and post-polio syndrome. The majority of the 19 participants were breast cancer survivors, diagnosed an average of 10 years earlier. The content analysis results are presented in three sections, according to each study aim (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic Information (N = 19)

| N | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.5 (9.6) | |

| Age when diagnosed with primary disabling condition (years) | 37.5 (14.5) | |

| Time since cancer diagnosis (years) | 9 (9.5) | |

| Focus group location | ||

| Austin, TX | 4 | |

| Villanova, PA | 4 | |

| Chicago, IL | 6 | |

| Ann Arbor, MI | 5 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 4 | |

| Asian American | 1 | |

| White | 13 | |

| Education | ||

| High school | 2 | |

| College or some college | 11 | |

| Masters or doctorate | 6 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 2 | |

| Widowed | 3 | |

| Married | 8 | |

| Divorced | 5 | |

| Live with significant other | 1 | |

| Source of functional impairment | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | 4 | |

| Arthritis | 3 | |

| Post-polio syndrome | 3 | |

| Spinal cord impairment | 2 | |

| * Other | 7 | |

| Type of cancer | ||

| Breast | 11 | |

| Colorectal | 2 | |

| Bladder | 2 | |

| Gynecologic | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 1 | |

| Thyroid | 1 | |

| Kidney | 1 | |

| ** Type of cancer treatment | ||

| Surgery | 18 | |

| Chemotherapy | 7 | |

| Radiation | 8 |

Other sources included blindness, hearing impairment, chronic back pain, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, bacterial meningitis, and bone disease.

Most participants received more than one type of treatment.

Note: all participants were female.

Table 2.

Analytic Categories

|

Living With a Cancer Diagnosis

Four analytic categories were derived from the data: the double whammy, cancer care challenges associated with a pre-existing disability, the impact of cancer treatment, and the importance of advocacy and social support. The term, “double whammy,” refers to the experience of managing a cancer diagnosis on top of living with a chronic disabling functional limitation. This constituted a strong undercurrent throughout the group dialogues in all four focus groups. One participant said:

We all think we are dealing with more than one thing but sometimes if we have a physical handicap, physically, you are dealing with a double whammy in a way that other people can’t understand. You’re already stressed out trying to deal with polio problems or, you know, “Oh my gosh I’ve gotta get a CAT scan but there is no parking nearby. How can I get there?” My strength is already gone from having the polio and now you have to deal with your cancer, so it’s heavier to deal with.

Other participants made similar observations and discussed the devastating impact of receiving a cancer diagnosis and struggling to manage both clinical care issues and the emotional effects of a dual diagnosis. Comments included, “It seems like it is always something [else];” and “Oh my God, here we go;” and “I don’t want to do one more thing, but I guess that’s not a choice.”

The cancer diagnosis and treatment experience precipitated challenges for the participants. They recounted difficulties in obtaining care from cancer care providers who seemed unable to understand or accommodate the needs of persons with pre-existing functional limitations and disabling diseases.

I was already experiencing post-polio syndrome and probably about 18 surgeries [before breast cancer surgery] but I am angry because I feel no matter what I say to any person in the medical profession, it goes in one ear and out the other perhaps because they haven’t had the personal experience to believe what I’m saying is still important.

This participant then described a harrowing experience with post-anesthesia care following breast surgery that illustrated staff misunderstanding of her respiratory compromise associated with post-polio syndrome. Some described difficult hospitalization experiences in which providers appeared indifferent to participants’ needs for assistance with self-care activities; others described problems with accessing facilities that had substantial barriers for people with mobility and visual impairments. Many worried about their oncologists’ ability to recommend cancer treatment that took their underlying diseases into account. One woman with MS worried about managing her MS treatment regimen along with her breast cancer care:

It was difficult to sort through what medicines I was taking for MS versus what medicines I was going to be taking for cancer and ended up sorting through those and figuring out which ones I could leave off for the MS and that was in the cancer cartel.

Participants described their experiences with cancer treatments within the context of their pre-existing conditions. Many recounted challenges associated with post-surgical care:

So, getting though the treatment, I stayed with friend of mine who is a nurse, as I was on crutches and it was hard with my MS because I don’t have a whole lot of upper body strength. So the crutches weren’t the most ideal things for me to have, so that made it difficult, too.

The difficulty of decisions about chemotherapy and radiation therapy also surfaced. Some participants explained how these treatments adversely impacted their already compromised functional mobility and energy levels:

It’s cumulative. You have fatigue anyway, but just with chemo and radiation, it just takes its toll. And that’s scary to lose. You may gain it back when you quit, but sometimes not.

Finally, the importance of advocacy and social support was clear within the double whammy context. Participants described their efforts to be their own advocates and educate their cancer care providers about their pre-existing conditions. One woman struggled with obtained appropriate pain medication when she had a mastectomy and reconstructive surgery. Although the pain medication regimen for her chronic arthritic pain worked well, hospitalization for cancer surgery created new problems:

The fact that I’m on this pain control regimen, doctors wanted to ignore it, I’m sure they wanted to ignore it, he didn’t want to deal with somebody with Fentanyl patch and Oxycodone, just didn’t want to deal with that. So if you don’t advocate for yourself, forget it.

She later observed, “Sometimes you get tired of fighting for yourself and trying to educate everybody.” Others echoed this sentiment, yet emphasized the need to “become your own case manager and advocate.” Important social support for surviving the added challenges of a cancer experience included family, friends, and spiritual connections. “It’s important to have somebody you trust to go through the process with you for the cancer treatment and when you’re doing intense procedures and making treatment decisions.”

Health Promotion Strategies

Strategies that participants used to promote health while surviving cancer included physical activity, nutritional support, management of their health care providers and medical regimens, and lifestyle adjustment. Examples of preferred physical activities included walking, water exercise, biking, and swimming. However, some of these activities posed a challenge due to functional limitations and problems with accessibility of health clubs and other exercise settings. Participants with neuromuscular disorders shared their difficulties in finding warm water swimming pools. However, the participants from Chicago mentioned a local fitness center that emphasized accessibility and focused on the needs of people with disabilities. Their experiences underscore the major role the environment plays in health promotion for people with disabilities. Dietary strategies varied somewhat, but typically included the importance of eating fruits and vegetables, foods without additives, and dietary supplements.

The importance of managing multiple health care providers and medical regimens dominated much of the discussion. Participants encountered cancer care providers insensitive to their other medical needs and limitations. As participants moved through cancer treatment and beyond, they emphasized the importance of communication in coordinating care between specialists and primary care providers. Determining the etiology of new symptoms was particularly challenging in the context of multiple diagnoses managed by different specialists.

One of the things I really don’t like about MS, it just makes you almost sound like a martyr if you really sit down and talk to a doctor and say “here’s what I’m feeling”. And sometimes they say “well that’s just life.” Well, no, I don’t think so, you know, it isn’t. Adding on the cancer problems makes you think you could either hide and just keep quiet or really kind of assert, “No, I really think you need to look at this; you need to allow the possibility that there may be some additional problems here”.

Health promotion strategies also included life-style adjustments such as stress reduction, energy conservation, and requesting help. Participants explained that stress and fatigue diminished their sense of wellness and that they engaged in activities such as relaxation exercises, pacing activities throughout the day to allow for periodic rest, yoga, and acupuncture. Some described having been reluctant to reach out to others for emotional support or assistance with cancer care needs. They observed that they had learned to overcome such reluctance and change their hesitancy to accept help. One described responding to an offer of meals from her son’s school:

I said “Oh No! I don’t need that. No, I’m not getting sick from chemo and I’m fine.” And one woman was so persistent. Finally I agreed to one meal per week and you know what? And that was the most wonderful thing. And it took a load off my mind.

Wellness Program Development for Survivors with Pre-Existing Functional Limitations

Participants reviewed the proposed topics (Figure 1) for a wellness program tailored to their needs and offered feedback and further suggestions. Although they concurred with the proposed topics, they emphasized the importance of teaching individuals how to manage their care via self-advocacy and education, and to find accessible health care settings with providers sensitive to their needs.

Getting to the doctors is a huge issue. I had stopped seeing my surgeon because his office is not accessible. I now question if I had to go through radiation and chemotherapy again, how would I do it, not being as mobile as I was, when I did have a cancer for the first time.

They offered caveats about the physical activity and nutrition topics, including the importance of tailoring activities and nutritional intake to meet unique needs and limitations and how to find resources for assistance with this. Participants also suggested topics specific to cancer, including the importance of ongoing cancer surveillance, use of survivor support groups, management of economic and insurance issues unique to individuals with multiple chronic conditions, and dealing with the fear of possible cancer reoccurrence.

To me it’s a concern in the economics of the health care industry when you have a chronic disabling condition and you also have cancer. Is there going to be limitations on what gets covered? If you already look on the bottom line on your insurance and you’re one of the people that the numbers are a little bigger… are there going to be things that are going to be curtailed?

Discussion

The diagnosis of cancer along with a pre-existing functional limitation represented a double whammy for these participants. Difficulties in finding health care providers equipped to manage both the cancer and other underlying conditions surfaced in the four focus groups. This finding is similar to that of Iezzoni and colleagues, who showed that mobility impairment and physical access barriers can adversely impact the process of diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from breast cancer (Iezzoni et al., 2010; Iezzoni, Park, & Kilbridge, 2011). Unfortunately, many health care providers are poorly prepared to care for people with prior disabling conditions. Barriers to good care include negative attitudes about working with people with disabilities, communication barriers, and lack of disability-related training and teaching materials in academic nursing and medical programs (Iezzoni, 2006; Larson, Carrothers, & Premo, 2002; Martin, Rowell, Reid, Marks, & Reddihough, 2005; Shakespeare, Iezzoni, & Groce, 2009; Smeltzer, Robinson-Smith, Dolen, Duffin, & Al-Maqbali, 2010).

In a recent American Cancer Society survey, both primary care physicians and oncologists reported concerns about being adequately prepared to provide appropriate cancer survivor care (Virgo, Lerro, Klabunde, Earle, & Ganz, 2011). Nonetheless, provision of health promotion services to cancer survivors is an integral component of survivorship care (Ganz, Casillas, & Hahn, 2008; McCabe & Jacobs, 2008). New educational efforts must be made to provide nurses and other health care providers with skills and tools to care for survivors who may have multiple co-morbidities and functional limitations. In addition, implementation of oncology nurse navigation services for these survivors with complex medical conditions has great potential for removing barriers to care, improving interdisciplinary communication, and enhancing care outcomes (Lee et al., 2011; Pedersen & Hack, 2010). As such, future studies should evaluate the impact of navigation services in this population.

The concept of self-advocacy appeared in the discussion of all of the focus group questions. Survivors spoke at length of trying to educate cancer care providers about their unique needs and included self-advocacy as a health promotion strategy and an important component of wellness programs for cancer survivors with pre-existing functional limitations. This importance of self-advocacy has been found in other studies of healthcare experiences in people with functional impairments (Sharts-Hopko, Smeltzer, Ott, Zimmerman, & Duffin, 2010) and was characterized as “fighting for everything” in a study of women severely affected by multiple sclerosis (Edmonds, Vivat, Burman, Silber, & Higginson, 2007). Self-advocacy has long been identified as important for cancer survivors (Hoffman & Stovall, 2006). As such, nurses who design wellness programs for cancer survivors with other pre-existing conditions must address self-advocacy strategies for both sets of needs. Such strategies can be as simple as providing participants with names of care settings that successfully accommodate persons with functional limitations (e.g., having adjustable exam tables that allow easier transfer from a wheelchair) or as complex as teaching advocacy strategies to influence public policy.

The participants suggested that wellness programs include an emphasis on managing the economic impact of having both a cancer diagnosis and a pre-existing co-morbid condition that may also necessitate ongoing care interventions. Worries about dual diagnoses prompted concerns about insurability and growing out-of-pocket expenses not covered by third-party payers. This concern is supported by a recent study of health disparities in access to care for cancer survivors in the U.S.; investigators found that over 2 million cancer survivors did not access one or more needed medical services because of financial troubles (Weaver, Rowland, Bellizzi, & Aziz, 2010). Although wellness programs for cancer survivors should include existing strategies for obtaining necessary care, health policy changes must support appropriate care for the growing number of cancer survivors and persons with disabilities. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 is designed to improve accessibility, quality, and affordability of health care for persons with disabilities (American Association of People with Disabilities, 2011); however, political and judicial challenges to the Act leave its fate uncertain.

In sum, the concept of health promotion resonated with study participants. They provided multiple examples of how they work to take care of their health. Their challenges to staying healthy offer areas where nurses and other health care providers can partner with them to enhance their health. Given the possibility that various forms of cancer-related disability and altered function may have an added effect on pre-existing disabilities, future studies should investigate this phenomenon further and address how to best promote health in these complex cancer survivors.

Limitations

The present findings are limited to its participants’ voices. Because participants were mostly white, well-educated women living in urban/suburban areas with high-quality healthcare facilities, larger studies including more diverse groups are warranted. Although the focus group format capitalizes on a social context that encourages participants to reflect on one another’s ideas, it may also limit the information any one participant can share or inhibit the expression of minority opinions (Patton, 2002).

Conclusion

This study reveals nuances associated with the experience of a cancer diagnosis within the context of a pre-existing functional limitation. As survivors told about this “double whammy,” they revealed important lessons for their health care providers. Health promotion strategies encompassed many of the tactics that other cancer survivors employ, yet the need for adapting such measures to the unique issues associated with functional limitations and preexisting, often debilitating chronic diseases is evident. Suggestions for modifying wellness programs for these cancer survivors include attention to the pre-existing conditions as well as the challenges of the physical, emotional, social, and economic sequelae of a cancer diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to the following individuals who assisted with the focus groups: Dr. James Rimmer, University of Illinois at Chicago, Dr. Suzanne Smelzer, Villanova University College of Nursing, Lisa Wetzel-Effinger, Villanova University College of Nursing, Dr. Claire Kalpakjian, University of Michigan, Mary Burton, University of Michigan, Carolyn Grawi, Ann Arbor Center for Independent Living, Yochai Eisenberg, University of Illinois at Chicago, Dr. Carol Gill, University of Illinois at Chicago, Vijay Vasudevan, University of Illinois at Chicago, Shauna O’Neal, The University of Texas at Austin, Tiffany Scott, The University of Texas at Austin, Ana Todd, The University of Texas at Austin.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, 1R21CA133381, Dr. Becker, PI.

References

- Alfano CM, Day JM, Katz ML, Herndon JE, Bittoni MA, Oliven JM, Paskett ED. Exercise and dietary change after diagnosis and cancer-related symptoms in long-term survivors of breast cancer: CALGB 79804. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:128–133. doi: 10.1002/pon.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of People with Disabilities. Health reform explained. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.aapd.com/site/c.pvI1IkNWJqE/b.6125841/k.5AB9/Health_Reform_Explained.htm.

- Becker H, Kang S, Stuifbergen A. Predictors of quality of life for long-term cancer survivors with preexisting disabling conditions. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39:E122–E131. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E122-E131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearley SG, Stamataki Z, Addington-Hall J, Foster C, Hodges L, Jarrett N, Amir Z. The physical and practical problems experienced by cancer survivors: A rapid review and synthesis of the literature. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2011;15:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault M. Americans with disabilities: 2005. 2008 Retrieved from U.S. Census Bureau website: http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p70-117.pdf.

- Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Pescatello SM, Ferrer RA, Johnson BT. Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention. 2011;20:123–133. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikos TN, Roetzheim RG, McCarthy EP, Iezzoni LI. Cost disparities in lung cancer treatment by disability status, sex, and race. Disability and Health Journal. 2008;1:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Porock DC, McDaniel R, Nielsen PJ. A meta-analysis of exercise interventions among people treated for cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;45:699–712. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drainoni M, Lee-Hood E, Tobias C, Bachman SS, Andrew J, Maisels L. Cross-disability experiences of barriers to health-care access: consumer perspectives. J. ournal of Disability Policy Studies. 2006;17:101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, Silber E, Higginson IJ. 'Fighting for everything': Service experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2007;13:660–667. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Wright D, Hill H, Hopkinson J, Roffe L. Psychosocial implications of living 5 years or more following a cancer diagnosis: A systematic review of the research evidence. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2009;18:223–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Casillas J, Hahn EE. Ensuring quality care for cancer survivors: Implementing the survivorship care plan. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2008;24:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff D, Battaglini C, Sipe C, Peppercorn J, Anderson M, Hackney A. “Finding a new normal”: Using recreation therapy to improve the well-being of women with breast cancer. Annual in Therapeutic Recreation. 2009;18:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Harding M. Health-promotion behaviors and psychological distress in cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39:E132–E140. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E132-E140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SE, Watson EK, Ward AM, Khan NF, Turner D, Adams E, Rose PW. Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: A questionnaire survey. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2091–2098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Ganz P. From cancer patient to cancer survivor - Lost in transition: An American Society of Clinical Oncology and Institute of Medicine Symposium. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B, Stovall E. Survivorship perspectives and advocacy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:5154–5159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni LI. Make no assumptions: Communication between persons with disabilities and clinicians. Assistive Technology. 2006;18:212–219. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2006.10131920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni L, Kilbridge K, Park E. Physical access barriers to care for diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women with mobility impairments. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37:711–717. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.711-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni LI, Ngo LH, Li D, Roetzheim RG, Drews RE, McCarthy EP. Early stage breast cancer treatments for younger Medicare beneficiaries with different disabilities. Health Services Research. 2008a doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni LI, Ngo LH, Li D, Roetzheim RG, Drews RE, McCarthy EP. Treatment disparities for disabled Medicare beneficiaries with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008b;89(4):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni LI, Park ER, Kilbridge KL. Implications of mobility impairment on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Journal Of Women's Health. 2011;20:45–52. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson M, Carrothers L, Premo B. Providing primary health care for people with physical disabilities: A survey of California physicians. Pomona, CA: Center for Disability Issues and the Health Professions; 2002. Retrieved from http://www.cdihp.org/pdf/ProvPrimeCare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Ko I, Lee I, Kim E, Shin M, Roh S, Chang H. Effects of nurse navigators on health outcomes of cancer patients. Cancer Nursing. 2011;34:376–384. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit L, Smith AP, Benz EJJr, Ferrell B. Ensuring quality cancer care through the oncology workforce. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2010;6:7–11. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SY, Clark MA. Breast and cervical cancer screening practices among disabled women aged 40–75: Does quality of the experience matter? Journal of Women's Health. 2008;17:1321–1329. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HL, Rowell MM, Reid SM, Marks MK, Reddihough DS. Cerebral palsy: What do medical students know and believe? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2005;41:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: Models and programs. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2008;24:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy EP, Ngo LH, Chirikos TN, Roetzheim RG, Li D, Drews RE, Iezzoni LI. Cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among persons with Social Security Disability Insurance on Medicare. Health Services Research. 2007;42:611–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pederson A, Hack TF. Pilots of oncology care: A concept analysis of the patient navigator role. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37:55–60. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosedale M. Survivor loneliness of women following breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2009;36:175–183. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare T, Iezzoni LI, Groce NE. Disability and the training of health professionals. Lancet. 2009;374:1815–1816. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)62050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharts-Hopko NC, Smeltzer S, Ott BB, Zimmerman V, Duffin J. Healthcare experiences of women with visual impairment. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2010;24:149–153. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181d82b89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, Stein KD, Kaw C, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: A report from the American Cancer Society's Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:2779–2790. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short PF, Vasey JJ, Belue R. Work disability associated with cancer survivorship and other chronic conditions. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:91–97. doi: 10.1002/pon.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeltzer SC, Robinson-Smith G, Dolen MA, Duffin JM, Al-Maqbali M. Disability-related content in nursing textbooks. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2010;31:148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuifbergen AK, Becker H, Rogers S, Timmerman G, Kullberg V. Promoting wellness for women with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 1999;31:73–79. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuifbergen AK, Harrison T, Becker H, Carter P. Adaptation of a wellness intervention for women with chronic disabling conditions. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2004;22:12–31. doi: 10.1177/0898010104263230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuifbergen AK, Morris M, Jung JH, Pierini D, Morgan S. Benefits of wellness interventions for persons with chronic and disabling conditions: a review of the evidence. Disability and Health Journal. 2010;3:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuifbergen AK, Seraphine A, Harrison T, Adachi E. An explanatory model of health promotion and quality of life for persons with post-polio syndrome. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Disability and health. 2011 Retrieved from http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=9.

- Virgo KS, Lerro CC, Klabunde CN, Ganz PA. Barriers in providing breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care: Perceptions of US primary care physicians and medical oncologists. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(supp) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6954. CAR9006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM. Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:3493–3504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]