Abstract

Immune cell-mediated tissue injury is the common feature of different inflammatory diseases, yet the pathogenetic mechanisms and cell types involved vary significantly. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) represents a group of inflammatory diseases that are characterized by increased numbers of pathogenic eosinophilic granulocytes in the peripheral blood and diverse organs. Based on clinical and laboratory findings, various forms of HES have been defined, yet the molecular mechanism and potential signaling pathways that drive eosinophil expansion remain largely unknown. Here we show that mice deficient of the serine/ threonine-specific protein kinase NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) develop a HES-like disease, reflected by progressive blood and tissue eosinophilia, tissue injury and premature death at around 25–30 weeks of age. Similar to the lymphocytic form of HES, CD4+ T-cells from NIK-deficient mice express increased levels of T-helper 2 (Th2)-associated cytokines, and eosinophilia and survival of NIK deficient mice could completely be prevented by genetic ablation of CD4+ T-cells. Experiments based on bone marrow chimeric mice, however, demonstrated that inflammation in NIK-deficient mice depended on radiation-resistant tissues, implicating that NIK-deficient immune cells mediate inflammation in a non-autonomous manner. Surprisingly, disease development was independent of NIKs known function as IkappaB kinase (IKK)-α kinase, as mice carrying a mutation in the activation loop of IKKα, which is phosphorylated by NIK, did not develop inflammatory disease. Our data show that NIK activity in non-hematopoietic cells controls Th2-cell development and prevents eosinophil-driven inflammatory disease, most likely using a signaling pathway that operates independent of the known NIK substrate IKKα.

Introduction

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) represents a group of rare diseases characterized by increased numbers of eosinophils in the peripheral blood and tissue in the absence of known causes of eosinophilia, such as parasitic helminth infection or allergic disorders (1). The clinical manifestations vary significantly depending on the severity of the eosinophilia and the organs affected, and range from cutaneous symptoms, such as eczema, pruritus and angioedema to pulmonary, gastrointestinal and cardiac complications (2–4). Depending on the clinical presentation, laboratory findings and response to treatment, several distinct subtypes can be distinguished, the two most common forms being the myeloproliferative and the lymphocytic variants of HES (2, 4, 5). While the eosinophilia observed in the myeloproliferative form is due to an intrinsic defect in eosinophils, the lymphocytic variant of HES is characterized by an expansion of T-helper (Th) 2-biased CD4+ T-cells that aberrantly produce high levels of interleukin (IL)-5, which in turn mediate secondary eosinophilia (5–9). As such, the lymphocytic variant of HES appears to be a Th2-mediated inflammatory disease.

CD4+ T-cells play key roles in the regulation of physiological immune responses, but also contribute to immune-pathology as observed during chronic inflammatory diseases, e.g. autoimmune and atopic diseases, or the above mentioned HES. Dependent on factors provided by the cell environment, activation of naïve CD4+ T-cells leads to differentiation into various Th subsets, such as Th1 or Th2 cells that exert distinct effectors functions (10). Interferon (IFN) γ-secreting Th1 cells are particularly important for immune responses against intracellular pathogens, whereas Th2 cells, which preferentially produce cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, support growth and effector functions of eosinophils and mast cells. Hence, Th2 cells are critically involved in immune responses triggered by helminthes or allergens. While an aberrant T-cell differentiation into Th2 cells most likely causes the secondary blood and tissue eosinophilia and subsequent organ dysfunction observed during HES, the etiology of the initial Th2 T-cell deregulation is less well understood.

As described in this paper, we found that mice deficient of the serine/threonine-specific kinase NIK develop a spontaneous progressive HES-like disease with blood and tissue eosinophilia accompanied by organ destruction and premature death. NIK is a key component of the so-called alternative NF-κB signaling pathway (11–14) that is induced by a subset of TNFR family members, including BAFF-R, LTβR, CD40 and RANK, which control diverse functions, including development of the lymphatic system. (15–19). Alymphoplasia (Nikaly/aly) mice, which harbor a loss of function mutation in Nik (20, 21), and NIK-deficient mice, lack lymph nodes, show disorganized spleen and thymus architecture, and B-cells derived from these mice exhibit impaired maturation and survival (20, 22–29). Activation of mentioned TNFR family members leads to stabilization and activation of NIK, which phosphorylates and activates IKKα (14, 30). Activation of IKKα in turn leads to phosphorylation and limited proteolysis of NF-kB2/ p100, resulting in the release of the RELB-binding N-terminal p52 moiety. The heterodimer of p52 and RELB translocates to the nucleus and initiates gene transcription (31). Accordingly, Nik−/− and Nikaly/aly mice show a complete defect in p100 processing ((12) and unpublished data). Nikaly/aly mice were shown to develop a spontaneous inflammatory disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltrations in various organs (32–34), which has been attributed to a failure of the alternative NF-κB pathway in the thymic stroma enviroment, resulting in combined defects in negative and positive selection of autoreactive and regulatory T-cells (Treg), respectively (22, 24). Despite the development of this spontaneous inflammatory condition, also referred to as ‘autoimmune disease’, Nikaly/aly mice are refractory to disease development in autoimmune disease models of arthritis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and graft-versus host disease (35–38), which in part may be explained by reduced production of IL-2 by T-cells from NIK-deficient mice, as well as reduced generation of Th17 cells (22, 24, 36, 39). The resistance of NIK-deficient mice to disease development in autoimmune disease models, however, appeared to reflect a less well characterized function of NIK in dendritic cells (DC), rather than a T-cell intrinsic defect (35). Nevertheless, adoptive transfer of CD4+ Nikaly/aly T-cells into Rag2−/− mice (34) was found to be sufficient to induce inflammatory disease, suggesting that NIK deficient CD4+ T-cells exert a hitherto uncharacterized effector function that triggers inflammatory disease.

We sought to further study the inflammatory disease development in Nik−/− mice and to determine the role of CD4+ T-cells in disease progression. We found that inflammation in NIK deficient mice, as reflected by increased numbers of leukocytes in peripheral blood and diverse tissues, was largely due to increased eosinophil numbers, thereby resembling a progressive HES-like disease, eventually resulting in tissue destruction and premature death. In this paper we characterize the eosinophilic inflammation in NIK-deficient mice, the phenotype of Nik−/− CD4+ T-cells and the contribution of radiation-resistant and hematopoietic tissue to inflammatory disease development. Furthermore, we investigate the role of NIK’s known downstream target, i.e. IKKα, for its contribution to disease. Together, our data suggest that NIK’s function in radiation-resistant tissue is essential for prevention of T-cell mediated HES-like disease, which however does not depend on NIK’s known function as an IKKα kinase.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Nik−/− mice (Map3k14tm1Rds), generated by Yin and colleagues (26), were kindly provided by Amgen and backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 mice background for 9 generations. IKKαAA/AA mutant mice (40) were a kind gift from Michael Karin (University of California, San Diego, CA). C57BL/6 mice and Rag1−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). MHC class II−/− mice (B6.129-H2-Ab1tm1Gru) and SJL (SJL/JCrNTac) mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY). Mice were kept under pathogen free conditions and survival and disease development were monitored for the indicated time points. Disease onset was determined by signs of thickening of the eyelids, fur loss or skin rash. All animal studies were conducted under protocols approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

T-cell isolation

Single cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen by straining tissues through a 100 µm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Red blood cells were lyzed using LCK lysis buffer (Lonza) and CD4+ T cells were isolated by positive selection with anti-CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FCS (Hyclone), 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and antibiotics (penicillin G (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin sulfate (100 IU/ml), Invitrogen).

Cytokine measurement

Purified CD4+ T-cells were stimulated with plate-bound αCD3/αCD28 (10µg/ml, eBioscience) for 72 hours and the concentration of IL-5, IL-10, IFNγ (BD Biosciences), IL-4 and IL-13 (eBioscience) was determined from the supernatant by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histology and Complete Blood Cell Counts

16 weeks-old mice were perfused with 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Tissues were sectioned at 5 µm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), rat anti-mouse MBP polyclonal antibody (clone MT-14.7, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) or goat anti-mouse CD3 (Santa Cruz) to detect eosinophil and T-cell infiltrations respectively. Peripheral blood was collected by retroorbital bleeding. Complete blood cell counts (CBC) were measured using the Forcyte Hematology System (Oxford Science). Differential blood counts were determined manually by a trained pathologist by microscopic examination of Wright’s stained peripheral blood smears. At least 100 white blood cells were counted.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single cell suspensions of the spleen were prepared and blocked with antibodies against CD16/CD32 (eBioscience), followed by staining for cell surface expression of CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (RM4–5), GR-1 (Ly6G, RB6-8C5), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MAL-14) (eBioscience) and CD8 (53-6.7), Siglec-F (E50-2440), CCR3 (CD193) (83103) (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Generation of bone marrow chimera mice

Bone marrow chimeras were generated by reconstituting irradiated (950 Gy) 6- to 10-week-old CD45.1+SJL or CD45.2+Nik−/− recipient mice with 1x106 bone marrow cells from SJL or Nik−/− donor mice. Chimerism was verified by analysis of CD45.2 expression on peripheral blood cells by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ±SEM and were compared using Student’s t test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

NIK deficient mice develop progressive systemic eosinophilia

Mice lacking functional NIK were shown to develop an inflammatory multiorgan disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltrations in various organs, such as the liver, lung, pancreas and the salivary glands (32–34). Here we sought to further characterize the development of inflammatory disease in Nik−/− mice over time, including the cellular composition of the leukocytic organ infiltrations and the role of T-cells in this process. We found that NIK deficient mice develop a progressive disease characterized by thickening of the eyelids, fur loss and skin inflammation around 11.4 ± 0.6 weeks resulting in premature death around 21.2 ± 5 weeks (Fig. 1, A and B). There was no significant difference in disease development between male and female mice (Fig. 1C). Complete and differential blood counts showed a 1.9-fold increase in white blood cells in Nik−/− mice; interestingly, this increase was due to elevated numbers of myeloid cells, in particular the number of monocytes and eosinophils, which were increased 4.5-fold and 7.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 1D). Eosinophils displayed a typical surface phenotype of GR-1int Siglec-F+ cells with variable expression levels of CCR3, possibly reflecting different maturation stages (Fig. 1E)(41). No significant difference was detectable in the number of neutrophilic granulocytes or lymphocytes in the peripheral blood. Histological examination revealed that virtually all organs were infiltrated with mononuclear cells. Consistent with results obtained from Nikaly/aly mice (33), these infiltrates contained CD3+ T-cells (Fig. 1F and G); importantly, however, the infiltrates also contained eosinophilic granulocytes, as confirmed by MBP staining, which were dominating in all organs investigated (Fig. 1F and G).

FIGURE 1. NIK deficient mice develop a progressive inflammatory disease characterized by blood and tissue eosinophilia and premature death.

A, Thickening of the eyelids, fur loss and skin inflammation as typically observed in Nik−/− mice at around 12 weeks of age. B, Survival curve of Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice. C, Age at disease onset as determined by thickening of eyelids, fur loss or skin inflammation in male and female mice. D, White blood cell count (WBC) and differential cell count of peripheral blood of 12–16 weeks old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice. NE, neutrophilic granulocytes; LY, lymphocytes; MO, monocytes; EO, eosinophils; n=9, data represent mean±SEM. E, Flow cytometry analysis of spleens of 12 week old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice for immature (GR-1int Siglec-F+ CCR3−) and mature (GR-1int Siglec-F+ CCR3+) eosinophils. n=5, data represent mean±SEM. F, Representative H&E stain and eosinophil-specific anti-MBP stain of indicated organs of 16 week old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice. All images are shown at 40x magnification. G, Representative T-cell specific anti-CD3 stain of the lung and liver of 16 week old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice shown at 40x magnification.

Particularly strong infiltrations were seen in the lung (perivascular, interstitial and alveolar), liver (portal), spleen and skin, which were accompanied by apparent alterations of the physiological tissue structure and integrity (Fig. 1F and G). Taken together, Nik−/− mice develop a progressive blood and tissue eosinophilia accompanied by multiorgan damage and premature death.

T-cells in NIK deficient mice exhibit a Th2-biased phenotype and a reduced CD4+/ CD8+ ratio

As shown above, Nik−/− mice develop infiltrations of T-cells and eosinophils in multiple organs. Given that Th2-cell-derived IL-5 is a major maturation and differentiation factor for eosinophils we next evaluated the cytokine profile of CD4+ T-cells isolated from the spleen of Nik−/− and littermate control mice in response to αCD3/αCD28 stimulation. We found significantly increased levels of IL-5, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-10 and reduced levels of IFNγ in supernatants of Nik−/− CD4+ T-cells (Fig. 2A). This apparent Th2 bias of Nik−/− T-cells was already detectable in two week old mice, thereby preceding symptoms of described inflammatory disease, which becomes apparent at around 11 weeks of age (Fig. 1B and 2B).

FIGURE 2. Th2-biased T-cell phenotype and reduced CD4+/ CD8+ T-cell ratio in NIK-deficient mice.

A, Purified CD4+ T-cells from 6–16 week old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice were left untreated (co) or stimulated with αCD3/αCD28 for 72 hours and cytokine levels were determined by ELISA. n=9, data represent mean±SEM, *p≤0.005, **p≤0.001, ***p≤0.0005. B, Purified CD4+ T-cells from 2 week old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice were stimulated with αCD3/αCD28 in triplicate wells and analyzed as described in A. C, Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes from 6–12 week old Nik+/+ and Nik−/− mice. Total splenocytes (left panel), CD3+-gated cells (middle panel) or CD3+ CD4+-gated cells (right panel) are shown. n=3, data represent mean±SEM. CD8+ NIK+/+ vs. CD8+ NIK−/− *** p=0.0005, CD4+ NIK+/+ vs. CD4+ NIK−/− *** p= 0.0002.

Overall, the progressive blood and tissue eosinophilia in the presence of a Th2-biased T-cell phenotype in Nik−/− mice resembled the human lymphocytic form of HES. Since this form of HES has also been found to be associated with a decrease in the CD4+/ CD8+ ratio in several HES patients (7) we next determined the percentage of CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ T-cells in the spleen by flow cytometry. Indeed, we found a reduced CD4+/ CD8+ T-cell ratio in NIK deficient mice, while the overall percentage of CD3+ cells was comparable between wildtype (wt) and Nik−/− mice (Fig. 2D). We also observed a consistent reduction in the number of CD62Llow CD44high effector memory T-cells in Nik−/− mice, a phenotype which has not described in HES patients so far (Fig 2.D). Additional atypical T-cell subpopulations as described in select patients with the lymphocytic form of HES, such as CD3−CD4+, CD3−CD8+ or CD3+ CD4− CD8− populations were however not detected in Nik−/− mice (7).

Taken together, Nik−/− mice display a T-cell phenotype similar to the one observed in the lymphocytic human form of HES, with CD4+ T-cells producing high levels of Th2-associated cytokines, including IL-5, and a reduced CD4+/ CD8+ T-cell ratio.

CD4+ T-cells are critically involved in the development of inflammatory disease in Nik−/− mice

To further determine whether the spontaneous progressive eosinophilia and Th2 bias in Nik−/− mice is the result of an intrinsic defect of Nik−/− eosinophils or due to described changes in T-cell biology, we crossed Nik−/− mice into T-cell deficient mice and examined survival, development of eosinophilia and multiorgan inflammation. Intercrossing Nik−/− mice into both, Rag1−/− mice, which lack T- and B-cells, as well as into MHC class II (MHCII) deficient mice, which lack CD4+ T-cells, completely protected the mice from disease development (Fig. 3A-D). While Nik−/− Rag1+/+ and Nik−/− MhcII+/+ mice succumbed to disease between 16–36 weeks, Nik−/− Rag1−/− mice as well as Nik−/− MhcII−/− mice were completely protected from premature death (Fig. 3, A and C). Accordingly, histological analysis of Nik−/− Rag1−/− mice and Nik−/− MhcII−/− mice showed no signs of inflammation or eosinophilic infiltration in any organs, as shown for the lung and liver (Fig. 3, B and D and data not shown). These results show that CD4+ T-cells are critically involved in disease development in Nik−/− mice. The results also indicate that the progressive eosinophilia is not the result of an intrinsic defect in Nik−/− eosinophils, but rather the consequence of altered CD4+ T-cell biology.

FIGURE 3. Inflammation in Nik−/− mice depends on CD4+ T-cells.

A, Nik−/− mice were crossed to Rag1−/− mice and survival of offspring was monitored for 40 weeks. Nik−/− Rag+/+ (n=5), Nik−/− Rag−−/− (n=10). B, Histological analysis based on H&E and MBP staining of lung and liver of 16 week old Nik−/− Rag+/+ and Nik−/− Rag−/− mice. Representative data obtained from 6 mice are shown. C, Nik−/− mice were crossed to MhcII−/− mice and survival of offspring was monitored for 40 weeks. Nik−/− MhcII+/+ (n=10), Nik−/−MhcII−/− (n=10). D, Histological analysis based on H&E and MBP staining of lung and liver of 16 week old Nik−/− MhcII+/+ and Nik−/−MhcII−/− mice. Representative data obtained from 3 mice are shown.

Th2-deviation and inflammatory disease in Nik−/− mice depends on non-hematopoietic cells

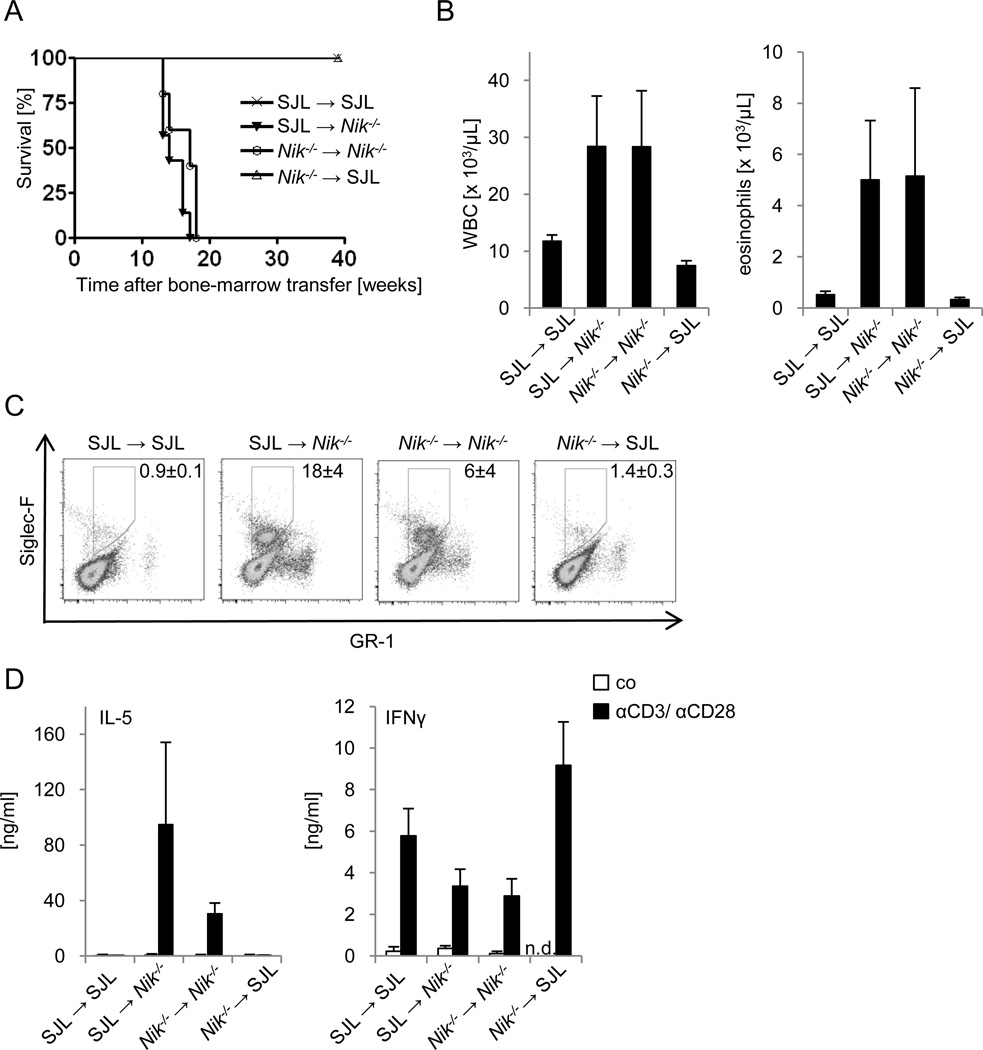

As shown by the experiments based on T-cell deficient mice, NIK-deficient eosinophils are not sufficient to mediate inflammatory disease, but depend on NIK-deficient CD4+ T-cells. To test whether inflammation is due to intrinsic defects of hematopoietic cells, including T-cells, we generated chimeric mice by adoptive transfer of bone marrow from CD45.1+ SJLwt and CD45.1− Nik−/− mice into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ SJL wt or CD45.1− Nik−/− recipient mice, and analyzed survival, T-cell dependent cytokine production and eosinophil expansion. As shown in Fig. 4, all phenotypic changes associated with the inflammatory disease described in Nik−/− mice correlated with the NIK-deficient genotype of radioresistant, non-hematopoietic tissues, but were not affected by the genotype of bone marrow-derived cells. Nik−/− mice that were reconstituted with SJL wt or NIK-deficient bone marrow cells died prematurely around 15 weeks after transfer (Fig. 4A). In contrast, SJL wt mice that had received bone marrow from SJL wt or Nik−/− mice survived without any apparent disease symptoms. Survival correlated with the appearance of increased numbers of eosinophils in the peripheral blood and spleen of Nik−/− mice, irrespective of the genotype of bone marrow cells transferred (Fig. 4B, C). Moreover, SJL wt and NIK-deficient CD4+ T-cells isolated from Nik−/− recipient mice produced very high levels of IL-5, while IFNγ levels were reduced (Fig. 4D). In contrast, SJL wt and NIK-deficient CD4+ T-cells isolated from SJL wt recipient mice produced much lower amounts of IL-5, but higher amounts of IFNγ (Fig. 4D). Thus, the major characteristics of the described HES-like disease found in Nik−/− mice depend on radio-resistant, non-hematopoietic cells, while T-cells and eosinophils are required for disease development, but are insufficient to trigger disease autonomously.

FIGURE 4. Radiation-resistant cells in NIK-deficient mice trigger inflammatory disease.

A, Lethally irradiated wt (SJL) and Nik−/− mice were reconstituted with bone marrow cells of the indicated genotypes, and survival was monitored for 40 weeks. n=4–7. B, White blood cell count and differential cell count of peripheral blood of bone marrow chimeric mice described in A at 8 weeks after bone marrow transfer. n=4–7, data represent mean±SEM. C, Splenocytes of bone marrow chimeric mice described in A were analyzed by flow cytometry 8 weeks after transfer. n=2–3, chimerism was >90%. Live cells were gated and are represented as mean±SEM. D, Purified CD4+ T-cells from bone marrow chimeric mice described in A were isolated 8 weeks after transfer and either left untreated (co) or stimulated with αCD3/αCD28 for 72 hours, and IL-5 and IFNγ levels were determined by ELISA. n=2–3, data represent mean±SEM.

Disease in Nik−/− mice proceeds independent of its downstream target IKKα

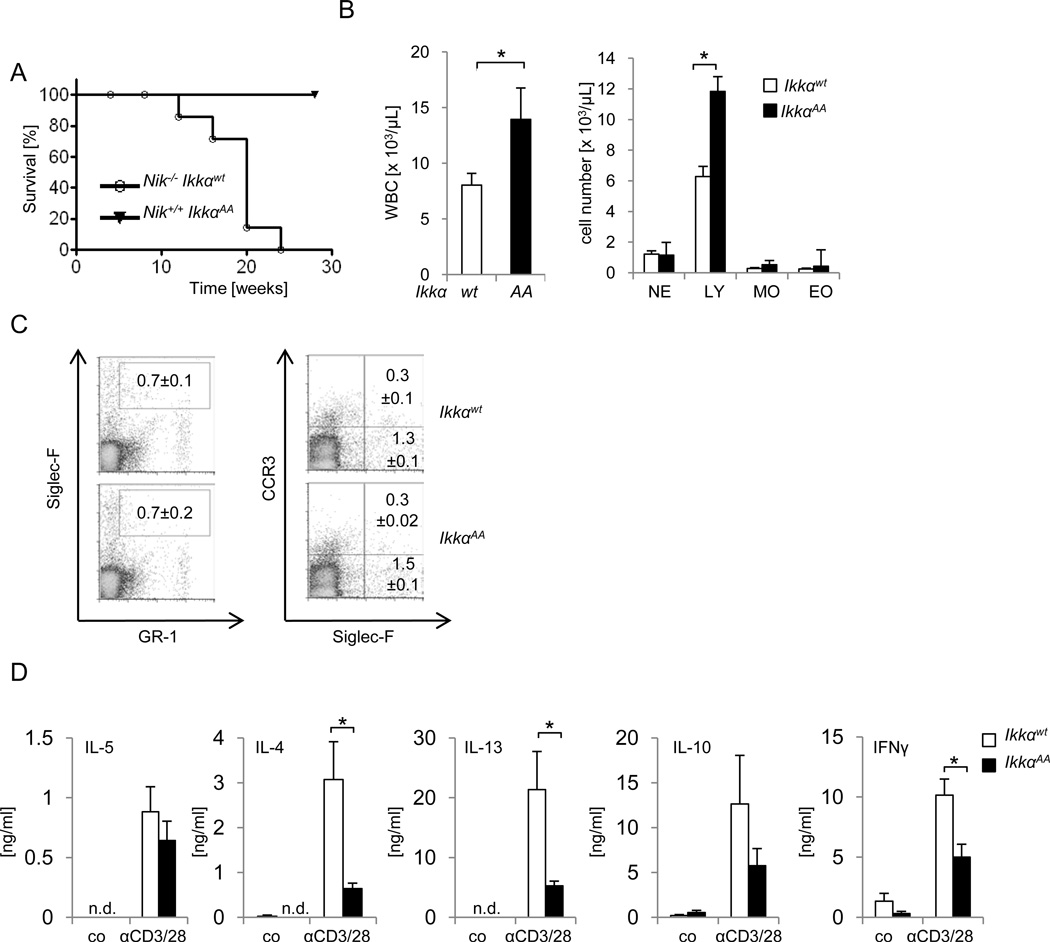

We next wanted to test if NIKs inhibitory role on Th2 development was mediated by its known function as IKKα kinase. Ikkα−/− mice die perinatally due to defects in skeletal and epidermal development (42–44). We therefore used IkkαAA/AA knock-in mice that carry point mutations in the IKKα activation loop (Ser176 /Ser180) thereby disabling NIK-mediated IKKα activation (11, 40). Comparable to cells from Ikkα−/− and Nik−/− mice, IkkαAA/AA cells exhibit defects in p100 processing; moreover, comparable to Nik−/− mice, IkkαAA/AA mice show defects in lymphoid organogenesis and B-cell maturation and survival (11). Interestingly, IkkαAA/AA mice neither died prematurely nor did they develop any of the typical skin and eye lesions observed in Nik−/− mice (data not shown). This was not due to residual differences in the background of the different mouse strains used, as offspring of intercrossings of Nik−/− mice and IkkαAA/AA mice showed the same phenotype (Fig. 5A and data not shown). While Nik−/− Ikkαwt/wt mice died between 12 and 24 weeks, no death was observed in the Nik+/+IkkαAA/AA mice for more than 30 weeks (Fig. 5A). More detailed analysis of the peripheral blood in IkkαAA/AA mice showed some increase in leukocyte numbers, which were however mainly due to increased numbers of lymphocytes, rather than granulocytes or monocytes (Fig. 5B). Eosinophil cell numbers in IkkαAA/AA mice were comparable to wt mice, both in peripheral blood and spleen, and no signs of eosinophilic organ infiltration were detected (Fig. 5B, C). We next analyzed the cytokine profile of CD4+ T-cells from IkkαAA/AA mice and their respective wt littermate controls. In contrast to the increased production of αCD3/αCD28-induced Th2 cytokines observed in Nik−/− CD4+ cells, IkkαAA/AA CD4+ T-cells did not show any increase in the release of Th2 cytokines (Fig. 5D). In fact, levels of both, Th1- and Th2-associated cytokines, i.e. IL-5, IL-4, IL-13, IL-10 and IFNγ, were reduced upon αCD3/αCD28 stimulation in comparison to their wt littermate controls. Taken together, the data implicate that NIK controls Th2 differentiation and inflammatory disease independent of its known function through IKKα phosphorylation.

FIGURE 5. Disease in Nik−/− mice proceeds independent of IKKα phosphorylation.

A, Nik−/− mice were crossed to IkkαAA/AA (IkkαAA) mice. Survival of Nik−/− Ikkαwt/wt (n=7), Nik−/− IkkαAA/AA (n=9) mice was monitored over 30 weeks. B, White blood cell count (WBC) and differential cell count of peripheral blood of 6–16 week old Ikkαwt/wt (wt) and IkkαAA/AA (AA) mice. NE, neutrophilic granulocytes; LY, lymphocytes; MO, monocytes; EO, eosinophils; n=7, data represent mean±SEM. C, Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes from 16 week old Ikkαwt/wt and IkkαAA/AA mice for immature (GR-1int Siglec-F+ CCR3−) and mature (GR-1int Siglec-F+ CCR3+) eosinophils, n=3, data represent mean±SEM. D, Purified CD4+ T-cells from 12–16 week old IKKαwt/wt and IKKαAA/AA mice were left untreated (co) or stimulated with αCD3/αCD28 for 72 hours and cytokine levels were determined by ELISA. n=5, data represent mean±SEM, *p≤0.005.

Discussion

In this study, we define NIK as an anti-inflammatory protein, whose function is essential for regulation of Th2-development and protection from Th2-associated inflammatory disease. This disease shares several key characteristics of human HES, including increased numbers of eosinophils in the peripheral blood, and eosinophilic infiltrations in virtually all organs including the skin, lung, liver and spleen. Eosinophilic infiltrations were accompanied by progressive changes in organ architecture and fibrosis, most likely a consequence of toxic mediators produced by eosinophils, such as eosinophil peroxidase or MBP (45, 46). Two earlier histological studies had described organ-specific eosinophilic infiltration in the stroma of the epididymis/ vas deferens (47) and in the skin (48) in Nikaly/aly mice, rather than revealing the general inflammation apparent in the Nik−/− mice described here. Whether these disparities reflect an incomplete defect of the signaling function of Nikaly/aly, which harbors a point mutation in the C-terminal part of NIK that contributes to IKKα binding (21, 49), or reflects the more restricted scope of mentioned studies is currently unclear.

Similar to the lymphocytic form of HES, Nik−/− CD4+ T-cells produce significantly increased levels of Th2 cytokines, including IL-5, which controls survival, maturation, recruitment, expansion and activation of eosinophils (Fig. 2A)(50, 51). Although IL-5 can be produced by other cell types such as basophils, mast cells and NK cells, the main producer of IL-5 and initiators of eosinophil recruitment into tissues appear to be Th2 T-cells, at least as far as investigated during allergic inflammation (52). A critical contribution of Th2 cells to the eosinophilia in Nik−/− mice is strongly supported by the observation that Nik−/− mice intercrossed into T-cell deficient mice, i.e. Rag1−/− mice and MhcII−/− mice, are resistant to eosinophilic inflammation and premature death (Fig. 3A-D). These data also suggest that expansion of eosinophils is not a cell-autonomous function of NIK-deficient eosinophils. Interestingly, experiments based on bone marrow chimeras further show that all parameters of the inflammatory disease described, i.e. Th2 deviation, eosinophil expansion and premature death, are triggered through radiation-resistant, but not hemotopoietic tissues. As such, inflammation observed in NIK-deficient mice is mediated by T- cells in a non-autonomous fashion. An important role for peripheral T-cells in the pathogenesis of the inflammatory disease in NIK mutant mice, sometimes referred to as ‘autoimmune disease’, has been supported by several animal and clinical studies. Adoptive transfer of Nikaly/aly CD4+ cells into Rag2−/− mice was shown to result in severe mononuclear cell infiltrations and tissue destruction in various organs 4–10 weeks after transfer (34). Also, HES patients have successfully been treated with agents that are known to suppress T-cell activation, e.g. cyclosporine or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA) (53–56), supporting the idea that T-cells contribute to HES disease.

Even though Nik−/− and Nikaly/aly mice develop a T-cell dependent inflammatory disease, the adaptive immune responses to foreign antigen were found to be impaired in these mice (29), and both, Nik−/− and Nikaly/aly mice, are resistant to EAE and graft versus host disease (35–37). Disease resistance was attributed to a failure to induce Th17 cells, and also to a reduced capacity to up-regulate IL-2 upon TCR activation, referred to as T-cell anergy. T-cell anergy was suggested to be a result of a defect in T-cell development due to altered function of NIK-deficient thymic DC (35). Consistent with these reports, we found that NIK-deficient CD4+ T-cells produce lower levels of IL-2 and IFNγ than wt cells upon αCD3/αCD28 stimulation (Fig. 2A and data not shown). However, we also found that reduced production of these cytokines was accompanied by exaggerated production of Th2 cytokines, strongly suggesting rather a classic Th2 deviation, than T-cell anergy as the primary phenotype of Nik−/− CD4+ T-cells. The role of NIK in the prevention of Th2 responses is further supported by the fact that gene-vaccination using NIK as an adjuvant induces Th1 immune responses (57).

Given the strong Th2 bias observed in Nik−/− mice one would assume a more efficient immune response upon worm infections, which are mediated primarily by Th2 cells, in NIK deficient mice. However, Th2 responses were also found to be impaired in Nikaly/aly mice in a model of Trichinella spiralis infection (58). Although described results may again reflect differences between Nik−/− and Nikaly/aly mice, another possibility is that more complex immune responses, as required during pathogen challenge, may depend on the integrity of various lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches, which are missing in NIK-deficient mice. As such, it is currently unclear whether impaired cellular immune responses to foreign antigen are due to an intrinsic defect in immune cells, including T-cells, or merely a consequence of described defects in lymphoid organ development.

Interestingly, the response of Nik−/− T-cells to foreign antigen in the EAE model could be restored upon expression of NIK in DC (35). Moreover, changes in DC cell biology in Nikaly/aly mice has also been reported by Tamura et al, who found that the overall number of DC, surface expression of CD80, CD86 and MHC class II, and the ability to present antigen was reduced in cells from Nikaly/aly mice (59), suggesting that NIK deficiency in DC leads to impaired adaptive immunity to foreign antigen. While NIK expression in DC seems to be important for the generation of adaptive immune responses to foreign antigen, NIK-expressing DC seem not to be the cause for the development of the spontaneous multiorgan inflammation observed in Nik−/− or Nikaly/aly mice ((28) and data shown here). Thymus transfer experiments showed that engraftment of thymus from Nikaly/aly mice in nude mice was sufficient to induce leukocytic organ infiltration, possibly reflecting the inflammatory disease described here for Nik−/− mice (28). Those results suggest that thymic stroma cells, specifically medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTEC), control the aberrant T-cell biology, rather than DC. Although it may in principle be possible that DC were also adoptively transferred as part of the organ, these thymic transfer experiments in combination with our results based on bone marrow chimeric mice, strongly suggests non-hematopoietic cells, most likely thymic stroma cells, as disease initiating factor.

In the above mentioned thymus transfer study, the multiorgan inflammation observed in NIK mutant mice was interpreted as a result of impaired tolerance induction and impaired generation of natural Treg (nTreg) due to reduced expression of the autoimmune regulator (Aire) in thymic stroma cells, which controls thymic expression of tissue restricted self antigens (28, 60). Although impaired tolerance induction and reduced levels of regulatory T-cells are feasible explanations for the inflammatory phenotype observed in NIK mutant mice, there are several observations that should be noted. First, although Aire−/− mice also develop a generalized inflammatory, autoimmune disease with lymphocytic infiltrations (61, 62), T-cells in these mice exhibit a prominent Th1 phenotype with enhanced secretion of IFNγ (63). Second, we did observe a similar decline in the number of Treg in IKKαAA/AA mutant mice (Supplementary Fig.1), which however do not develop signs of inflammation (Fig. 4). As such, it is unlikely that impaired tolerance induction and impaired generation of natural Treg (nTreg) due to reduced expression of Aire is the sole reason for observed Th2 deviation in Nik−/− mice. The data obtained from IkkαAA/AA mutant mice also support the idea that Treg numbers are regulated via a classic NIK-IKKα pathway, while the observed HES-like disease in NIK-deficient mice is not (see below).Taking our data and described studies together, it seems possible that the inflammatory phenotype of NIK−/− mice is the result of a combination of impaired deletion of self-reactive T-cells in a NIK-deficient thymus stroma environment, the absence of sufficient priming by DC towards Th1- and other T helper-fates, and the reduced numbers of Treg, which together leads to the expansion of autoreactive, Th2-biased T-cells and (consecutive) IL-5-driven eosinophils, which ultimately mediate a HES-like inflammatory disease.

Somewhat surprising, disease development in Nik−/− mice was independent of NIK’s classical function as an IKKα kinase, suggesting that NIK controls Th2 responses by mechanisms independent of phosphorylation and activation of IKKα. Characterized functions of NIK in the regulation of lymphoid organogenesis, B-cell development and generation of Th17 cells were all found to depend on critical phosphorylation in the activation loop of IKKα, which are mutated in IkkαAA/AA mice (11, 64). Although IKKα was shown to regulate effector functions independent of NIK (65), a signaling pathway allowing NIK to act independent of IKKα has not been characterized. In contrast to Nikaly/aly mice, a recent study found that IkkαAA/AA mutant mice mount normal primary antibody responses (66), suggesting that NIK might act independent of IKKα, at least in B-cells. Although our data do not entirely rule out the possibility that IKKα is required for NIK-dependent prevention of inflammation, it appears that the classic phosphorylation-dependent signaling cascade triggered through NIK-mediated IKKα phosphorylation is either not relevant, or compensated by other mechanisms, i.e. an IKKα-independent signaling pathway. More sophisticated mouse models, e.g. based on tissue specific IKKα knock-out strains, or biochemical identification of additional NIK substrates will be required to address this question.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Amgen and Michael Karin for providing us with the Nik−/− and IkkαAA/AA mice respectively. We also thank the ARC for animal care and assistance and the Veterinary Pathology histology core facility at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

This work was supported by the NIH grant AI083443 to H.H., and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Abbreviations used in this article

- HES

hypereosinophilic syndrome

- NIK

NF-kappaB-inducing kinase

- IKKα

IkappaB kinase α

References

- 1.Simon HU, Rothenberg ME, Bochner BS, Weller PF, Wardlaw AJ, Wechsler ME, Rosenwasser LJ, Roufosse F, Gleich GJ, Klion AD. Refining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 126:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2011 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 86:677–688. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH, Gleich GJ, Huss-Marp J, Kahn JE, Leiferman KM, Nutman TB, Pfab F, Ring J, Rothenberg ME, Roufosse F, Sajous MH, Sheikh J, Simon D, Simon HU, Stein ML, Wardlaw A, Weller PF, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;124:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.022. e1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM. The hypereosinophilic syndromes: current concepts and treatments. Br. J. Haematol. 2009;145:271–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. Recent advances in pathogenesis and management of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Allergy. 2004;59:673–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon HU, Yousefi S, Dommann-Scherrer CC, Zimmermann DR, Bauer S, Barandun J, Blaser K. Expansion of cytokine-producing CD4-CD8- T cells associated with abnormal Fas expression and hypereosinophilia. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1071–1082. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon HU, Plotz SG, Dummer R, Blaser K. Abnormal clones of T cells producing interleukin-5 in idiopathic eosinophilia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:1112–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cogan E, Schandene L, Crusiaux A, Cochaux P, Velu T, Goldman M. Brief report: clonal proliferation of type 2 helper T cells in a man with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;330:535–538. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrezenmeier H, Thome SD, Tewald F, Fleischer B, Raghavachar A. Interleukin-5 is the predominant eosinophilopoietin produced by cloned T lymphocytes in hypereosinophilic syndrome. Exp. Hematol. 1993;21:358–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Paul WE. Peripheral CD4+ T-cell differentiation regulated by networks of cytokines and transcription factors. Immunol. Rev. 238:247–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senftleben U, Cao Y, Xiao G, Greten FR, Krahn G, Bonizzi G, Chen Y, Hu Y, Fong A, Sun SC, Karin M. Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Sun SC. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-kappaB2 p100. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hacker H, Karin M. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re13. doi: 10.1126/stke.3572006re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hacker H, Tseng PH, Karin M. Expanding TRAF function: TRAF3 as a tri-faced immune regulator. Nat Rev Immunol. 11:457–468. doi: 10.1038/nri2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C, Li ZW, Karin M, Ware CF, Green DR. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayagaki N, Yan M, Seshasayee D, Wang H, Lee W, French DM, Grewal IS, Cochran AG, Gordon NC, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, Dixit VM. BAFF/BLyS receptor 3 binds the B cell survival factor BAFF ligand through a discrete surface loop and promotes processing of NF-kappaB2. Immunity. 2002;17:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claudio E, Brown K, Park S, Wang H, Siebenlist U. BAFF-induced NEMO-independent processing of NF-kappa B2 in maturing B cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:958–965. doi: 10.1038/ni842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novack DV, Yin L, Hagen-Stapleton A, Schreiber RD, Goeddel DV, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. The IkappaB function of NF-kappaB2 p100 controls stimulated osteoclastogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:771–781. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coope HJ, Atkinson PG, Huhse B, Belich M, Janzen J, Holman MJ, Klaus GG, Johnston LH, Ley SC. CD40 regulates the processing of NF-kappaB2 p100 to p52. EMBO J. 2002;21:5375–5385. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyawaki S, Nakamura Y, Suzuka H, Koba M, Yasumizu R, Ikehara S, Shibata Y. A new mutation, aly, that induces a generalized lack of lymph nodes accompanied by immunodeficiency in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:429–434. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinkura R, Kitada K, Matsuda F, Tashiro K, Ikuta K, Suzuki M, Kogishi K, Serikawa T, Honjo T. Alymphoplasia is caused by a point mutation in the mouse gene encoding Nf-kappa b-inducing kinase. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:74–77. doi: 10.1038/8780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Valdepenas C, Martin AG, Ramakrishnan P, Wallach D, Fresno M. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase is involved in the activation of the CD28 responsive element through phosphorylation of c-Rel and regulation of its transactivating activity. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4666–4674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Valdepenas C, Casanova L, Colmenero I, Arriero M, Gonzalez A, Lozano N, Gonzalez-Vicent M, Diaz MA, Madero L, Fresno M, Ramirez M. Nuclear factor-kappaB inducing kinase is required for graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica. 95:2111–2118. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada T, Mitani T, Yorita K, Uchida D, Matsushima A, Iwamasa K, Fujita S, Matsumoto M. Abnormal immune function of hemopoietic cells from alymphoplasia (aly) mice, a natural strain with mutant NF-kappa B-inducing kinase. J. Immunol. 2000;165:804–812. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koike R, Nishimura T, Yasumizu R, Tanaka H, Hataba Y, Watanabe T, Miyawaki S, Miyasaka M. The splenic marginal zone is absent in alymphoplastic aly mutant mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:669–675. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin L, Wu L, Wesche H, Arthur CD, White JM, Goeddel DV, Schreiber RD. Defective lymphotoxin-beta receptor-induced NF-kappaB transcriptional activity in NIK-deficient mice. Science. 2001;291:2162–2165. doi: 10.1126/science.1058453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura Y, Qu N, Terayama H, Naito M, Yi SQ, Moriyama H, Itoh M. Structure of thymic cysts in congenital lymph nodes-lacking mice. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2008;37:126–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2007.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajiura F, Sun S, Nomura T, Izumi K, Ueno T, Bando Y, Kuroda N, Han H, Li Y, Matsushima A, Takahama Y, Sakaguchi S, Mitani T, Matsumoto M. NF-kappa B-inducing kinase establishes self-tolerance in a thymic stroma-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 2004;172:2067–2075. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinkura R, Matsuda F, Sakiyama T, Tsubata T, Hiai H, Paumen M, Miyawaki S, Honjo T. Defects of somatic hypermutation and class switching in alymphoplasia (aly) mutant mice. Int. Immunol. 1996;8:1067–1075. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.7.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ling L, Cao Z, Goeddel DV. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase activates IKK-alpha by phosphorylation of Ser-176. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3792–3797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao G, Fong A, Sun SC. Induction of p100 processing by NF-kappaB-inducing kinase involves docking IkappaB kinase alpha (IKKalpha) to p100 and IKKalpha-mediated phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30099–30105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furukawa M, Sakamoto A, Kita Y, Ohishi Y, Matsumura R, Tsubata R, Tsubata T, Iwamoto I, Saito Y, Sumida T. T-cell receptor repertoire of infiltrating T cells in lachrymal glands, salivary glands and kidneys from alymphoplasia (aly) mutant mice: a new model for Sjogren's syndrome. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1996;35:1223–1230. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.12.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuneyama K, Kono N, Hoso M, Sugahara H, Yoshida K, Katayanagi K, Gershwin ME, Saito K, Nakanuma Y. aly/aly mice: a unique model of biliary disease. Hepatology. 1998;27:1499–1507. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsubata R, Tsubata T, Hiai H, Shinkura R, Matsumura R, Sumida T, Miyawaki S, Ishida H, Kumagai S, Nakao K, Honjo T. Autoimmune disease of exocrine organs in immunodeficient alymphoplasia mice: a spontaneous model for Sjogren's syndrome. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:2742–2748. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofmann J, Mair F, Greter M, Schmidt-Supprian M, Becher B. NIK signaling in dendritic cells but not in T cells is required for the development of effector T cells and cell-mediated immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1917–1929. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin W, Zhou XF, Yu J, Cheng X, Sun SC. Regulation of Th17 cell differentiation and EAE induction by MAP3K NIK. Blood. 2009;113:6603–6610. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greter M, Hofmann J, Becher B. Neo-lymphoid aggregates in the adult liver can initiate potent cell-mediated immunity. PLoS biology. 2009;7:e1000109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aya K, Alhawagri M, Hagen-Stapleton A, Kitaura H, Kanagawa O, Novack DV. NF-(kappa)B-inducing kinase controls lymphocyte and osteoclast activities in inflammatory arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1848–1854. doi: 10.1172/JCI23763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto M, Yamada T, Yoshinaga SK, Boone T, Horan T, Fujita S, Li Y, Mitani T. Essential role of NF-kappa B-inducing kinase in T cell activation through the TCR/CD3 pathway. J. Immunol. 2002;169:1151–1158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Y, Bonizzi G, Seagroves TN, Greten FR, Johnson R, Schmidt EV, Karin M. IKKalpha provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression during mammary gland development. Cell. 2001;107:763–775. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voehringer D, van Rooijen N, Locksley RM. Eosinophils develop in distinct stages and are recruited to peripheral sites by alternatively activated macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;81:1434–1444. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1106686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda K, Takeuchi O, Tsujimura T, Itami S, Adachi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Yoshikawa K, Terada N, Akira S. Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKalpha. Science. 1999;284:313–316. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Q, Lu Q, Hwang JY, Buscher D, Lee KF, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Verma IM. IKK1-deficient mice exhibit abnormal development of skin and skeleton. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1322–1328. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu Y, Baud V, Delhase M, Zhang P, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Johnson R, Karin M. Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKKalpha subunit of IkappaB kinase. Science. 1999;284:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frigas E, Motojima S, Gleich GJ. The eosinophilic injury to the mucosa of the airways in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma. Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 1991;13:123s–135s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valent P. Pathogenesis, classification, and therapy of eosinophilia and eosinophil disorders. Blood Rev. 2009;23:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itoh M, Miyamoto K, Ooga T, Iwahashi K, Takeuchi Y. Spontaneous accumulation of eosinophils and macrophages throughout the stroma of the epididymis and vas deferens in alymphoplasia (aly) mutant mice: I. A histological study. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1999;42:246–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1999.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi S, Ueda A, Ueda M, Nawa K. Pathology of spontaneous dermatitis in CBy.ALY-aly mice. Exp. Anim. 2008;57:159–163. doi: 10.1538/expanim.57.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luftig MA, Cahir-McFarland E, Mosialos G, Kieff E. Effects of the NIK aly mutation on NF-kappaB activation by the Epstein-Barr virus latent infection membrane protein, lymphotoxin beta receptor, and CD40. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:14602–14606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. The eosinophil. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:147–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gleich GJ. Mechanisms of eosinophil-associated inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000;105:651–663. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg HF, Phipps S, Foster PS. Eosinophil trafficking in allergy and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;119:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.048. quiz 1311-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donald CE, Kahn MJ. Successful treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome with cyclosporine. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2009;337:65–66. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318169569a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zabel P, Schlaak M. Cyclosporin for hypereosinophilic syndrome. Ann. Hematol. 1991;62:230–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01729838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nadarajah S, Krafchik B, Roifman C, Horgan-Bell C. Treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome in a child using cyclosporine: implication for a primary T-cell abnormality. Pediatrics. 1997;99:630–633. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ueno NT, Zhao S, Robertson LE, Consoli U, Andreeff M. 2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine therapy for idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leukemia. 1997;11:1386–1390. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andreakos E, Williams RO, Wales J, Foxwell BM, Feldmann M. Activation of NF-kappaB by the intracellular expression of NF-kappaB-inducing kinase acts as a powerful vaccine adjuvant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:14459–14464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603493103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Korenaga M, Akimaru Y, Shamsuzzaman SM, Hashiguchi Y. Impaired protective immunity and T helper 2 responses in alymphoplasia (aly) mutant mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Immunology. 2001;102:218–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamura C, Nakazawa M, Kasahara M, Hotta C, Yoshinari M, Sato F, Minami M. Impaired function of dendritic cells in alymphoplasia (aly/aly) mice for expansion of CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Autoimmunity. 2006;39:445–453. doi: 10.1080/08916930600833390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Metzger TC, Anderson MS. Control of central and peripheral tolerance by Aire. Immunol. Rev. 241:89–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Turley SJ, von Boehmer H, Bronson R, Dierich A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science. 2002;298:1395–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1075958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramsey C, Winqvist O, Puhakka L, Halonen M, Moro A, Kampe O, Eskelin P, Pelto-Huikko M, Peltonen L. Aire deficient mice develop multiple features of APECED phenotype and show altered immune response. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:397–409. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Devoss JJ, Shum AK, Johannes KP, Lu W, Krawisz AK, Wang P, Yang T, Leclair NP, Austin C, Strauss EC, Anderson MS. Effector mechanisms of the autoimmune syndrome in the murine model of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. J. Immunol. 2008;181:4072–4079. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li L, Ruan Q, Hilliard B, Devirgiliis J, Karin M, Chen YH. Transcriptional regulation of the Th17 immune response by IKK(alpha) J. Exp. Med. 208:787–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoshino K, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto M, Tanaka T, Saito M, Hemmi H, Ohara O, Akira S, Kaisho T. IkappaB kinase-alpha is critical for interferon-alpha production induced by Toll-like receptors 7 and 9. Nature. 2006;440:949–953. doi: 10.1038/nature04641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mills DM, Bonizzi G, Karin M, Rickert RC. Regulation of late B cell differentiation by intrinsic IKKalpha-dependent signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:6359–6364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700296104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.