Abstract

The synaptic cell adhesion molecules encoded by the protocadherin gene cluster are hypothesized to provide a molecular code involved in the generation of synaptic complexity in the developing brain. Variation in copy number and sequence content of protocadherin cluster genes among vertebrate species could reflect adaptive differences in protocadherin function. We have completed an analysis of zebrafish protocadherin cluster genes. Zebrafish have two unlinked protocadherin clusters, DrPcdh1 and DrPcdh2. Like mammalian protocadherin clusters, DrPcdh1 has both α and γ variable and constant region exons. A consensus protocadherin promoter motif sequence identified in mammals is also conserved in zebrafish. Few orthologous relationships, however, are apparent between zebrafish and mammalian protocadherin proteins. Here we show that protocadherin cluster genes in human, mouse, rat, and zebrafish are subject to striking gene conversion events. These events are restricted to regions of the coding sequence, particularly the coding sequences of ectodomain 6 and the cytoplasmic domain. Diversity among paralogs is restricted to particular ectodomains that are excluded from conversion events. Conversion events are also strongly correlated with an increase in third-position GC content. We propose that the combination of lineage-specific duplication, restricted gene conversion, and adaptive variation in diversified ectodomains drives vertebrate protocadherin cluster evolution.

The evolution of the vertebrate brain from its invertebrate ancestors required a vast increase in the number and complexity of neuronal subtypes, synaptic connections, and the neural networks they comprise (Nieuwenhuys et al. 1998). These advances likely involved the expansion of particular classes of genes involved in brain development as well as the emergence of novel genes. Differences in brain development and function among vertebrates may be attributable to adaptive differences in particular genes shared among many vertebrate species. The members of the protocadherin gene cluster are compelling candidates to provide the molecular code required for the generation and maintenance of synaptic specificity in brain development (Kohmura et al. 1998; Wu and Maniatis 1999). The human protocadherin (Pcdh) gene cluster consists of 53 tandemly arrayed, single-exon paralogous genes organized into three subclusters, designated α, β, and γ, on chromosome 5 (Wu and Maniatis 1999). Each large, “variable” exon encodes an extracellular domain consisting of six cadherin-like ectodomain repeats, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic tail. At the 3′ end of both the α and γ subclusters are an additional three short exons that are alternatively cis-spliced to each α and γ variable exon, providing a “constant” cytoplasmic region (Wu and Maniatis 1999; Tasic et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002a). Each variable exon is transcribed from its own promoter, and all protocadherin cluster promoters share a highly conserved core motif (Wu et al. 2001; Noonan et al. 2003). The organization and gene content of the mouse and human protocadherin clusters are similar, indicating that the function of protocadherin cluster genes in brain development is conserved among all mammals (Wu et al. 2001).

Protocadherin proteins are thought to form homophilic interactions at synapses, providing a molecular means to distinguish subsets of neurons based on the combinations of protocadherins they express (Obata et al. 1995; Kohmura et al. 1998). Recent advances in the understanding of protocadherin function evoke a more sophisticated version of this hypothesis (Wang et al. 2002b; Phillips et al. 2003). Mice bearing a homozygous deletion of the Pcdhγ cluster show normal brain development and synaptogenesis until late in the embryonic stage (Wang et al. 2002b). We recently determined that 21% of Europeans carry a deletion of three α protocadherin genes, Pcdhα8, α9, and α10, with no apparent phenotypic effect (Noonan et al. 2003). Late-embryonic-stage mice that are null for all of the Pcdhγ genes, however, suffer massive apoptosis of spinal interneurons and show some evidence of neurodegeneration in the brain (Wang et al. 2002b). Spinal interneurons, but not hippocampal neurons, lacking the Pcdhγ cluster die in culture, indicating a direct requirement for Pcdhγ proteins in neuronal survival (Wang et al. 2002b). A significant proportion of Pcdhγ expression is nonsynaptic and intracellular, indicating that these proteins have other functions besides synaptic cell adhesion (Wang et al. 2002b; Phillips et al. 2003). Studies of hippocampal neurons in culture, however, show Pcdhγ proteins localized at subsets of excitatory synapses (Phillips et al. 2003). Pcdhγ proteins are also expressed on presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes at a subset of excitatory synapses in the hippocampus. In these cases, Pcdhγ proteins may mediate cell–cell interactions (Phillips et al. 2003). Protocadherin α and γ transcripts and proteins are expressed in overlapping but distinct patterns in the brain, and individual neurons have been shown to express multiple Pcdhα proteins (Kohmura et al. 1998; Tasic et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002b). These results suggest a new model in which Pcdh proteins are required for neuronal maturation and synaptic modification rather than synaptogenesis (Wang et al. 2002b; Kallenbach et al. 2003; Phillips et al. 2003). In this model, protocadherin cluster proteins are not structural components of synapses, but serve to identify and modify an enormous number of neuronal and synaptic subpopulations in the developing and adult brain (Phillips et al. 2003).

The protocadherin cluster is one example of a striking feature of vertebrate genomes: the presence of tandem arrays of paralogous genes encoding proteins of similar function that provide combinatorial complexity to some biological system. The classic examples, immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene clusters, generate the enormous range of antigen recognition molecules required to mount an effective immune response in an environment of multiple, rapidly evolving pathogens (for review, see Flajnik 2002). Olfactory receptor gene clusters provide the molecular means to detect minute amounts of numerous odorants, such as chemoattractants and toxins (Buck and Axel 1991). Each of these tandem arrays encode proteins involved in highly specific interactions such as receptor-ligand, antibody-antigen, and, for protocadherins, cell adhesion and possibly ligand recognition (Senzaki et al. 1999). Specificity in these interactions requires sequence diversity among paralogs, which generates the molecular and biological diversity the cluster provides. Diversity among protocadherin cluster paralogs provides the information comprising the hypothesized protocadherin synaptic code. Mechanisms that generate diversity among paralogs in a tandem array, increasing or decreasing the information content in that array, include gene duplication, diversification among duplicated paralogs, and gene conversion (Ohno 1970; Ohta 1980; Slightom et al. 1980; Nei et al. 1997). These processes are often lineage-specific, resulting in differences in gene number and sequence content even among closely related species. Differences in olfactory receptor gene number are common even among primate species, and these genes have undergone considerable gene conversion events in humans (Sharon et al. 1999; Newman and Trask 2003). Protocadherin cluster genes show variable copy number among mouse, rat, and human, with an expansion of the Pcdhβ cluster in mouse and rat and an additional Pcdhα gene in rat (Wu et al. 2001; our present results). Differences in gene number and sequence diversity may be greater among more distantly related vertebrate species, and these differences may reflect adaptive differences in protocadherin function.

To investigate the diversity of vertebrate protocadherin cluster genes and the mechanisms that drive protocadherin cluster evolution, we are determining the structure of the protocadherin clusters in multiple vertebrate species. Protocadherin clusters are absent from the genomes of invertebrate model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, and also from the genomes of invertebrate chordates such as Ciona savignyi (Hill et al. 2001). Therefore, the protocadherin cluster may be a vertebrate innovation, driving the substantial increase in central nervous system complexity in vertebrates relative to other species. We have completed sequencing and assembly of a cluster of protocadherin genes in zebrafish, and have constructed maximum likelihood phylogenies of zebrafish, human, mouse, and rat protocadherin cluster proteins. We find that some general features of mammalian protocadherin clusters, including variable and constant region exon structure, are conserved in zebrafish. However, our results also indicate that lineage-specific adaptive variation, gene duplication, and especially gene conversion all contribute to extensive differences in protocadherin cluster variable exon sequence content among diverse vertebrate species.

RESULTS

Characterization of Zebrafish Protocadherin Cluster Genes

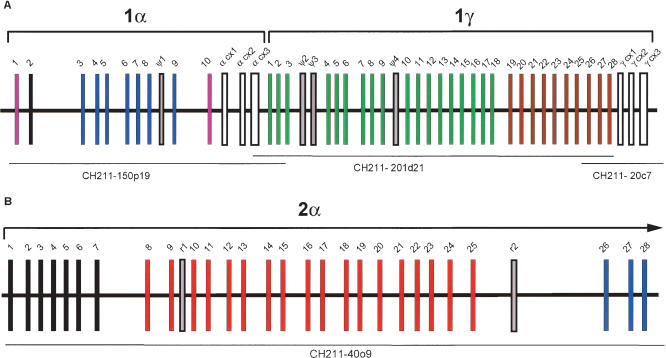

Teleosts have undergone a whole-genome duplication event in their evolution (Amores et al. 1998). This raises the possibility that zebrafish and other teleosts possess two divergent protocadherin clusters, as opposed to a single cluster as occurs in terrestrial vertebrates. Consistent with this hypothesis, we have identified 66 predicted protocadherin variable exon sequences arrayed in two unlinked clusters, DrPcdh1 and DrPcdh2, in the zebrafish genome. Here we provide the general organization of DrPcdh1 and DrPcdh2 and their relationship to mammalian protocadherin clusters. Both zebrafish Pcdh clusters are similar to protocadherin clusters in mammals, including, in the case of DrPcdh1, the characteristic arrangement of variable and constant exons. The DrPcdh1 cluster maps to linkage group 10 (LG10; Zebrafish Genome Fingerprinting Project; see Methods) and consists of 38 predicted variable exon sequences distributed in two subclusters, DrPcdh1α and DrPcdh1γ (Fig. 1A). By complete sequencing, we found 10 variable DrPcdh1α exons and one pseudogene followed by three short constant region exons. These constant exons encode a predicted polypeptide that is 60% identical to the human Pcdhα constant region. DrPcdh1γ is located directly 3′ of DrPcdh1α and consists of 28 variable exons and three predicted pseudogenes, followed by three short exons encoding a predicted polypeptide 53% identical to the human Pcdhγ constant region. We also completed sequencing and assembly of a BAC clone that maps to LG14 and contains an additional 28 predicted protocadherin variable exons (Fig. 1B). These exons are clearly part of a distinct second protocadherin cluster in zebrafish, DrPcdh2.

Figure 1.

Organization of protocadherin gene clusters in zebrafish. Subgroups of paralogous variable exons are indicated by color. Constant region exons are in white. Pseudogenes (ψ) are in gray. (A) Zebrafish Pcdh1α and Pcdh1γ. (B) Partial zebrafish Pcdh2. Sequenced BAC clone names and their locations are shown below each gene cluster.

We searched GenBank and the zebrafish EST assemblies at the Washington University Zebrafish Genome Resources Project (see Methods) for ESTs corresponding to our gene predictions. We found ESTs corresponding to DrPcdh1α2, 1α7, 1α10, DrPcdh1γ19, 1γ20, 1γ21, DrPcdh2–1, 9, and 26. We also searched for ESTs containing α and γ constant region sequences. We found multiple ESTs containing the DrPcdh1γ constant region, as well as ESTs containing an α constant region that is 82% identical on the amino acid level to the DrPcdh1α constant region. These ESTs include transcripts in which DrPcdh2 variable exons are spliced to this second α constant region. Based on this result, these exons appear to comprise a second Pcdhα cluster, which we designate DrPcdh2α. The DrPcdh2α constant region is likely located 3′ of our DrPcdh2α BAC sequence. These results clearly indicate that there has been an expansion in the number of α protocadherin genes in zebrafish relative to mammals.

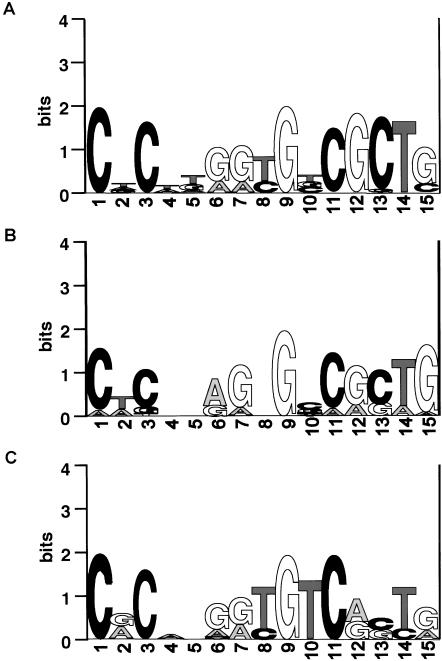

In mammals, each protocadherin variable exon has its own promoter (Wu et al. 2001; Tasic et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002a; Noonan et al. 2003). Each promoter and variable exon together form the fundamental protocadherin cluster repeat unit, which duplicates and subsequently diversifies in protocadherin cluster evolution. All mammalian protocadherin promoters are therefore paralogs, and, with few exceptions, share a common CGCT motif upstream of the transcription start site (Wu et al. 2001; Tasic et al. 2002). We selected 351 bp directly upstream of the predicted translation start of each zebrafish protocadherin variable exon and used MEME to search for shared motifs (Bailey and Elkan 1994). Figure 2 shows the results of MEME searches on human Pcdh (Fig. 2A), DrPcdh1 (Fig. 2B), and DrPcdh2α (Fig. 2C) proximal upstream sequences. Our results demonstrate that the CGCT motif in mammals is part of a larger 15-bp promoter element that is conserved among zebrafish and human protocadherin promoters. Comparing all three motifs, it is clear that particular bases are completely conserved at various positions in this element among almost all promoters examined. The CNC configuration at the 5′ end of the motif is almost universally conserved, as are the G two base pairs upstream of the CGCT element. Core promoter motifs in DrPcdh2α show some divergence from core motifs in mammalian and DrPcdh1 promoters (Fig. 2C). However, the overall level of conservation, spanning over 400 million years of evolution, indicates that the basic mechanism of protocadherin cluster regulation is highly conserved, even though the exons themselves are diverged.

Figure 2.

WebLogo plots of consensus mammalian Pcdh (A), DrPcdh1 (B), and DrPcdh2α (C) core promoter motifs identified using MEME. Mammalian Pcdh and zebrafish Pcdh1 promoter motifs are virtually identical, but the zebrafish Pcdh2α motif has a divergent CGCT box.

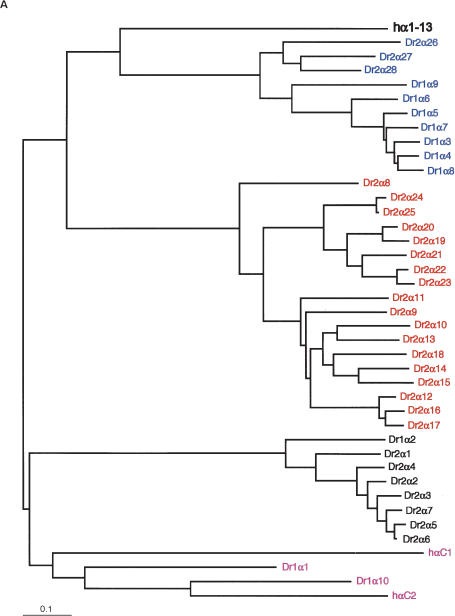

Phylogenies of mammalian protocadherin cluster genes usually reflect the evolutionary relationships among the species involved. For example, mouse and rat Pcdhα1 are more similar to each other than they are to human Pcdhα1, and all three are more similar to each other than they are to any other Pcdhα paralog (Wu et al. 2001; our present results). Orthologs are therefore identifiable across species. To determine the evolutionary relationship of zebrafish protocadherin cluster genes both to each other and to their mammalian counterparts, we translated each predicted variable exon in silico, removed the signal sequence, and made two large CLUSTALW alignments: one of DrPcdh1α, DrPcdh2α, and human Pcdhα proteins, and one of DrPcdh1γ, human Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ proteins. Human and zebrafish ectodomain and cytoplasmic sequences align well, with many substitutions but few gaps. We input these alignments into SEMPHY (Friedman et al. 2002; see Methods) and obtained the maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny for each, shown in Figure 3. Zebrafish protocadherin variable exons encode proteins with six cadherin-like ectodomains and a cytoplasmic domain of a size nearly identical to that of the comparable domains of mammalian protocadherins (data not shown). In most cases, however, zebrafish orthologs cannot be assigned to human protocadherin cluster proteins. In the ML tree of human and zebrafish Pcdhα proteins, human Pcdhα1–13 are grouped on their own branch separate from all DrPcdh1α and DrPcdh2α protocadherins (Fig. 3A). This topology could reflect independent expansions of protocadherin variable exons in each lineage, or lineage-specific adaptive differences in protocadherin ectodomain sequences. In contrast, human PcdhαC2 appears to have a definable zebrafish ortholog, DrPcdh1α10 (Fig. 3A). DrPcdh1α1 is also similar to human αC1 and αC2. There are five C-type protocadherins in humans and mice: αC1 and αC2 are located 5′ of the Pcdhα constant region, and γC3, γC4, and γC5 are located 5′ of the Pcdhγ constant region. These C-type variable exons are considerably diverged from other Pcdhα and Pcdhγ genes. DrPcdh1α10 is adjacent to the DrPcdh1α constant region, and its similarity to human αC2 indicates that the C-type protocadherins as a class are as ancient as α and γ protocadherins, and may be more highly conserved. However, the positioning of a C-type protocadherin, DrPcdh1α1, at the 5′ end of the DrPcdh1α cluster is a departure from the organization of C-type protocadherins in mammals.

Figure 3.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenies of zebrafish and human protocadherin cluster proteins. Members of paralog subgroups are indicated by color as in Figure 1. For clarity, subtrees of human protocadherin subgroups are shown as single branches in each tree, except for human C-type protocadherins, which are shown individually in purple. Trees are rooted by midpoint. (A) Protein tree of DrPcdh1α, DrPcdh2α, and human Pcdhα. (B) Protein tree of DrPcdh1γ, human Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ.

DrPcdh1α and DrPcdh2α descend from an ancestral tandem array duplicated in the teleost whole-genome duplication (WGD) event. Thus, we expected to see some interleaving of DrPcdh1α and DrPcdh2α proteins in this tree, reflecting their common ancestry. The tree topology, however, shows that either rapid diversification of genes between the duplicated clusters, or more likely post-WGD tandem duplications and deletions, occurred in each cluster. DrPcdh2α proteins consist of three paralog subclasses, 2α1–2α7, 2α8–2α25, and 2α26–2α28 (Fig. 3A). DrPcdh2α1–2α7 are most closely related to DrPcdh1α2, and clearly derive from subsequent duplications of the ancestral WGD-derived paralog. DrPcdh2α26–28 are closely related to DrPcdh1α3–1α9, and both groups also have arisen from additional cluster-specific expansions. DrPcdh2α8–2α25 are more distantly related to DrPcdh1α and human Pcdhα proteins. There has been a substantial expansion and diversification of Pcdhα protocadherins in zebrafish relative to humans, who have only 12 or 15 Pcdhα genes (Noonan et al. 2003).

In the ML tree of DrPcdh1γ, hPcdhβ, and γ protein sequences, for the most part zebrafish and human protocadherins are on separate nodes (Fig. 3B). Human Pcdhβ and γ proteins are more similar to each other than they are to any zebrafish protocadherin, indicating that β protocadherins are a mammalian, or at least terrestrial vertebrate, innovation. This is also true of the division of γ protocadherins into A and B subtypes, which are not present in zebrafish. DrPcdh1γ proteins fall into three separate paralogous subclasses: 1γ1–1γ3, 1γ4–1γ18, and 1γ19–1γ28. 1γ4–1γ18 are all highly similar to each other. Although they are related to mammalian Pcdhβ and Pcdhγ proteins, they have undergone considerable diversification, and many of these genes, such as 1γ16–1γ18, appear to be recent duplicates. 1γ19–1γ28 are related in the ML tree to human γC4 and γC5 (Fig. 3B). These genes may be the highly divergent descendants of an ancestral C-type protocadherin, or may comprise a distinct class of protocadherins not observed in mammals (Fig. 3B).

Distribution of Gene Conversion Events in Mammalian and Zebrafish Protocadherin Cluster Genes

Tandem gene arrays are subject to gene conversion, often as part of a process of concerted evolution in which paralogs in each species become more similar to each other than to their orthologs in related species (Smith 1974; Ohta 1980; Slightom et al. 1980; Fitch et al. 1990; Drouin et al. 1999). To determine the extent to which gene conversion contributes to the evolution of protocadherin cluster genes, we used GeneConv to search for shared identical elements among the members of the DrPcdh1α, DrPcdh1γ, DrPcdh2α, and mammalian Pcdhα, Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ paralog subclasses (Sawyer 1989). We found a very large number of elements greater than 95 nucleotides in length shared among paralogs within each group, with the same sequence element often shared among multiple paralogs (data not shown). Surprisingly, these elements are not randomly distributed throughout the coding regions of these genes, but are clustered at the 3′ end, involving sequences coding for ectodomains 5 and 6 as well as the cytoplasmic tail.

The number and distribution of these shared identical elements could be due to greater functional constraint on particular regions of each protein, residual similarity among very recent duplicates, or frequent gene conversion. Each of these possibilities yields testable predictions. Functional constraint at the protein level does not act on synonymous sites, which will therefore show a greater number of substitutions relative to nonsynonymous sites (Miyata et al. 1980). Constrained regions are also likely to be functionally orthologous, and therefore highly conserved, among closely related species. Recent duplicates are more similar across their entire length, not in particular regions (Nei et al. 1997). Gene conversion occurs within individuals and is more likely to happen between similar paralogs, as increased sequence similarity facilitates ectopic strand invasion (Ahn et al. 1988; Elliott et al. 1998). Therefore, orthology breaks down in converted regions, the opposite outcome of functional constraint.

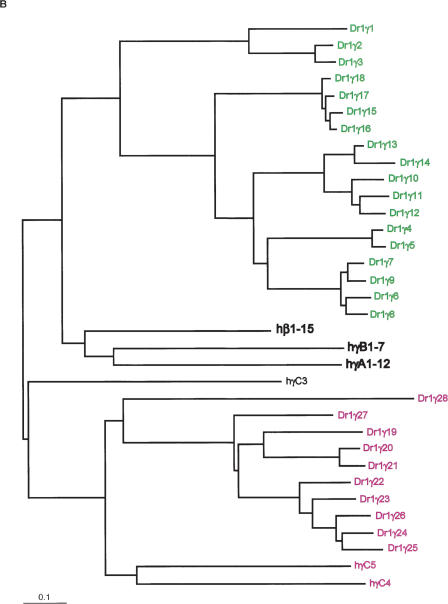

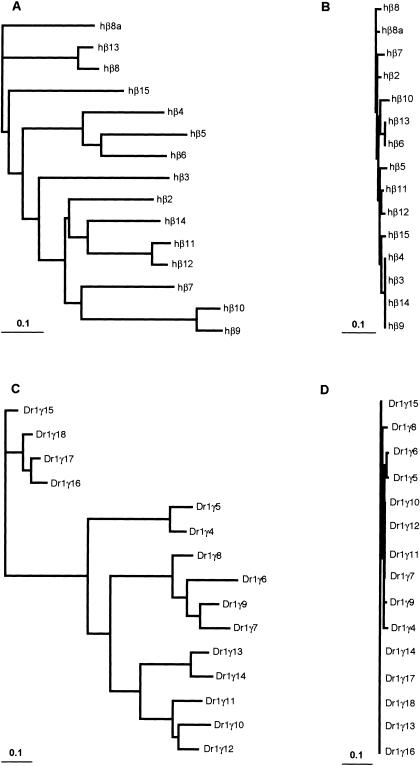

We built CLUSTALW protein alignments of each ectodomain (EC) and cytoplasmic domain from human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα, β, γA, and γB (excluding C-type protocadherins), DrPcdh1α3–1α9, DrPcdh1γ4–1γ18, DrPcdh1γ19–1γ27, and DrPcdh2α8–2α25. We built nucleotide alignments in RevTrans (see Methods) using each protein alignment as a template, and we generated ML gene trees for each ectodomain in SEMPHY. We observed substantial differences in the number of substitutions per site, depicted as branch lengths in each tree, among the ectodomains in each subgroup. Within each species, human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα ectodomains 1 and 5 are nearly identical, as are ectodomain 6 sequences among DrPcdh1α3–1α9 and DrPcdh2α8–α25. Human, mouse, and rat PcdhγA and PcdhγB paralogs also have homogenized sixth ectodomains. The ML gene trees for ectodomains 3 and 6 for human Pcdhβ and DrPcdh1γ 4–1γ18 are shown in Figure 4. Both human Pcdhβ (Fig. 4A) and DrPcdh1γ (Fig. 4C) paralogs are diverse in their third ectodomain, as expected from independent substitution in ancient duplicates. In contrast, ectodomain 6 is homogeneous within each group. Human Pcdhβ EC6 sequences are nearly identical (Fig. 4B); the branch lengths in this tree for β3, β4, β9, and β14 EC6 are zero, indicating a complete absence of substitutions among these sequences. This homogenization is even more extreme among DrPcdh1γ4-γ18 EC6 sequences (Fig. 4D). In both cases, paralogs that are considerably diverged in their third ectodomain, such as β4 and β9 (Fig. 4A,B) and DrPcdh1γ14 and DrPcdh1γ16 (Fig. 4C,D), have identical sixth ectodomains.

Figure 4.

Ectodomain-specific sequence homogenization in protocadherin cluster genes. The human Pcdhβ ectodomain (EC) 3 gene tree (A) reflects the sequence diversity among Pcdhβ paralogs. Pcdhβ ectodomain 6, however, is almost completely homogenized (B), with otherwise diverse Pcdhβ genes (e.g., β3 and β9) having identical EC6 sequences. This phenomenon is pronounced in zebrafish, where DrPcdh1γ genes with very divergent EC3 domains (C) have nearly identical EC6 domains (D).

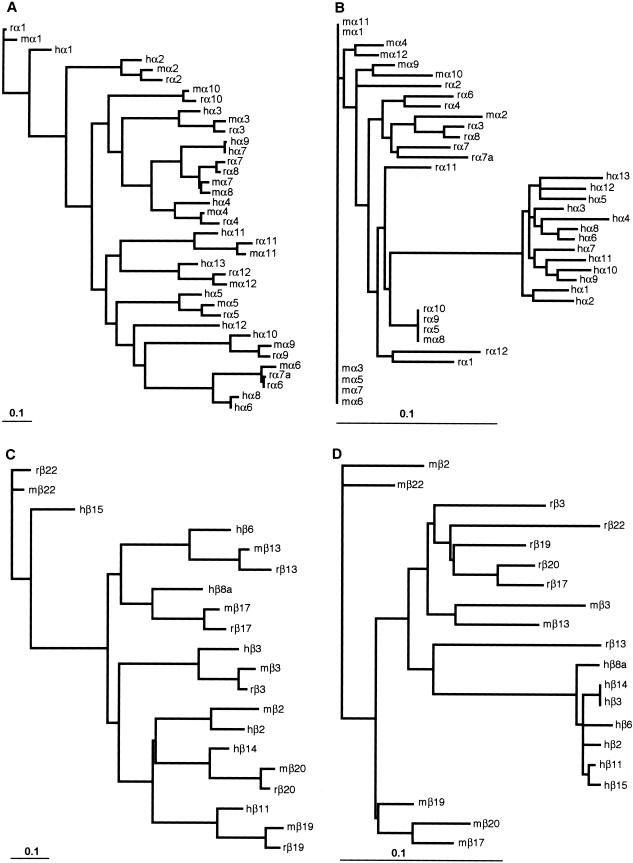

Our results demonstrate that ectodomain-specific sequence homogenization is a common feature of all protocadherin cluster genes. This sequence homogenization is also lineage-specific, resulting in nearly identical ectodomains among paralogs in the same species and divergence among homogenized ectodomains between orthologs. The orthologous relationships observed among full-length human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα genes are largely recapitulated in the EC3 gene tree (Fig. 5A). Orthology breaks down entirely, however, in ectodomain 5 (Fig. 5B), even between mouse and rat. For the most part, mouse and rat Pcdhα EC6 domains are more similar within each species, with complete homogenization evident among some paralogs (Fig. 5B). Breakdown of orthology is also evident in human, mouse, and rat Pcdhβ ectodomain 6 (Fig. 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Sequence homogenization in protocadherin cluster genes is lineage-specific. The gene tree of human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα (A) and Pcdhβ (C) EC3 domains recapitulates the orthologous relationships among the full-length genes. These relationships break down in Pcdhα EC5 (B) and Pcdhβ EC6 (D) domains, where paralogs within each species are more similar to each other than they are to their orthologs in related species.

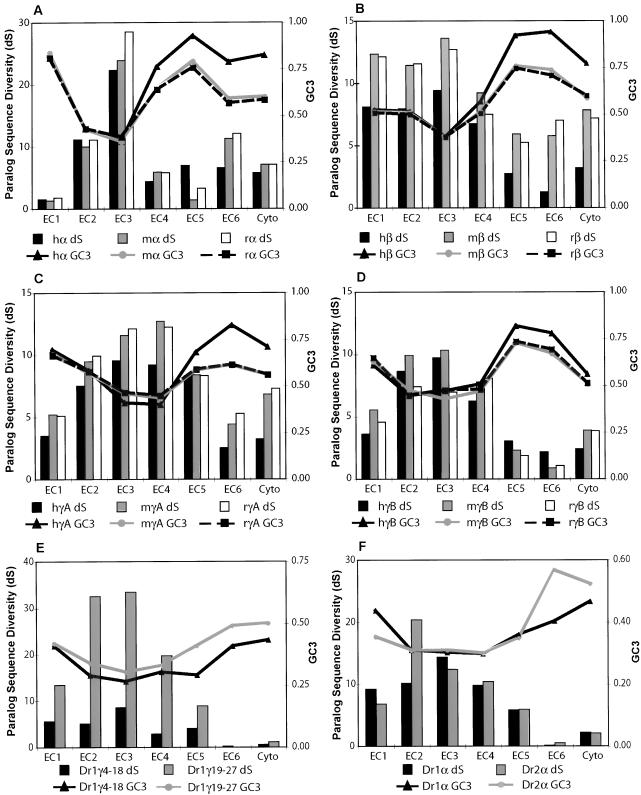

To determine whether the ectodomain- and lineage-specific homogenization we observe is due to functional constraint on protein sequences, we estimated the number of synonymous (dS) and nonsynonymous (dN) substitutions per site for each ectodomain gene tree and alignment by using codeml (Yang 1997). We then calculated the total sequence diversity at synonymous sites for each ectodomain in each paralog subgroup, expressed as the total length of the synonymous-site gene tree. Our results are shown in Figure 6. Within each subgroup in each species, neutral diversity varies substantially across domains. Different protocadherin subgroups also show different patterns of sequence homogenization. Human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα paralogs show very little neutral diversity in ectodomains 1, 4, and 5 (Fig. 6A), whereas Pcdhβ paralogs have divergent first ectodomains. In all cases, however, there is a strong trend toward reduced neutral diversity in 3′ ectodomain and cytoplasmic coding sequences. This is especially true for zebrafish protocadherins, which have almost completely homogenized EC6 and cytoplasmic sequences within each subgroup. In the most extreme case, the neutral diversity among DrPcdh2α8–2α25 ectodomain 6 sequences is zero (Fig. 6F). Ectodomain 3, however, shows no evidence of homogenization in any subgroup. EC3 provides most of the total neutral diversity among human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα paralogs (Fig. 6A), and appears to provide much of the phylogenetic signal between orthologs as well (Fig. 5A). The second and third ectodomains of DrPcdh2α8–2α25 are very divergent (Fig. 6F), in some cases only 50% identical on the protein level. The absence of a clear orthologous relationship between most mammalian and zebrafish protocadherins is not due to lineage-specific homogenization, as even the most divergent zebrafish ectodomains are more similar to each other than they are to any mammalian ectodomain (data not shown). Mammalian C-type protocadherins do not appear to be as subject to homogenization as other variable exons, but the limited number of C-type protocadherins in each species limits our ability to reliably detect conversion events in these genes (data not shown).

Figure 6.

The correlation of paralogous sequence diversity at synonymous sites and third-position GC content implicates gene conversion in Pcdh homogenization. Neutral paralog sequence diversity vs. third-position GC content (GC3) is shown for ectodomains 1–6 and the cytoplasmic domain from various protocadherin paralog subgroups. (A) Human, mouse, and rat Pcdhα. (B) Human, mouse, and rat Pcdhβ. (C) Human, mouse, and rat PcdhγA. (D) Human, mouse, and rat PcdhγB. (E) Zebrafish Pcdh1γ. (F) Zebrafish Pcdh1α and Pcdh2α.

Sequence homogenization at neutral sites strongly suggests that the patterns of homogenization we observe are the result of repeated gene conversion events, rather than functional constraint on protein sequence content. Gene conversion has been detected in genes coding for other cell adhesion molecules (Gally and Edelman 1992; Gallin 1998). Gene conversion is also indicated by the fact that homogenization is occurring among closely related paralogs, which are more likely to participate in ectopic conversion events due to their increased sequence similarity (Ahn et al. 1988; Elliott et al. 1998). In zebrafish, homogenization is also occurring among paralogs in close physical proximity (Figs. 1A,B; 6E,F), and gene conversion events between two paralogs appear to become more frequent as physical distance between the paralogs decreases (Galtier 2003). The localization of conversion events into discrete regions, however, suggests that a strong constraint exists on their distribution in protocadherin cluster genes.

Increased GC Content at Third Positions Accompanies Gene Conversion Events in Protocadherin Cluster Genes

There is substantial evidence that gene conversion events lead to increased GC content at codon third positions in the converted regions (Eyre-Walker 1993; Galtier et al. 2001; Smith and Eyre-Walker 2001; Birdsell 2002; Galtier 2003; Marais 2003). The molecular mechanism is unknown, but may be due to a GC bias in mismatch repair, which is required to resolve allelic and ectopic conversion events (Brown and Jiricny 1988; Sugawara et al. 1997; Galtier et al. 2001). Third positions are under little selective constraint and will therefore reflect this bias. We calculated average third-position GC content (GC3) for each ectodomain and cytoplasmic domain in each paralog subgroup and plotted it against neutral paralog sequence diversity, as shown in Figure 6. In each case we see the same trend: As diversity decreases, third-position GC content increases, such that there is an extreme bias in third-position GC content in homogenized regions. The average GC3 in the highly homogenized human Pcdhβ ectodomain 6 is 94%, compared to 38% in the divergent ectodomain 3 (Fig. 6B). This trend is consistent across species, with human, mouse, and rat protocadherin paralogs showing a nearly identical distribution of diversity and GC3 content (Fig. 6A–D). GC3 content is also elevated in homogenized zebrafish ectodomains (Fig. 6E,F), although the effect is apparently tempered by an overall AT bias in zebrafish (data not shown).

We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients between GC3 content and paralog ectodomain sequence diversity. Overall, we find a very strong negative correlation between paralogous neutral sequence diversity and third-position GC content in mammalian protocadherin cluster domains (Table 1). The correlation between GC3 and neutral sequence diversity for the human Pcdhβ paralogs is –0.98 (one-tailed P < 3e-6). There is a similar, albeit weaker, negative correlation in zebrafish protocadherin genes. The effect of this correlation is seen in Figure 6. In all mammalian paralog subgroups, ectodomains with high neutral sequence diversity have a GC3 value between 40% and 50%. Invariably, as neutral sequence diversity decreases, GC3 content increases. This is true even in ectodomains with intermediate neutral sequence diversity relative to the most divergent and most homogenized ectodomains. In these moderately homogenized domains, GC3 content increases, but is not as high as it is in completely homogenized ectodomains. These data strongly indicate that the level of neutral sequence diversity in a particular ectodomain is determined by the degree to which gene conversion events are maintained in that ectodomain, which also determines the level of bias in GC3 content. In zebrafish, GC3 content is not as tightly correlated with neutral sequence diversity. GC3 content is invariant in some cases even among ectodomains with varying neutral sequence diversity (Fig. 6E). In completely homogenized ectodomains, however, GC3 content increases substantially (Fig. 6E,F).

Table 1.

Pearson Correlation (r) Between Synonymous Paralogous Sequence Diversity and Third Position GC Content (GC3) for Protocadherin Cluster Paralog Subgroups

| Subgroup | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| hPcdhα1-13 | -0.837 | 0.006 |

| hPcdhβ2-15 | -0.984 | 3.00E-06 |

| hPcdhγA1-12 | -0.855 | 0.004 |

| hPcdhγB1-7 | -0.780 | 0.014 |

| mPcdhα1-12 | -0.886 | 0.002 |

| mPcdhβ2-22 | -0.936 | 0.0003 |

| mPcdhγA1-12 | -0.905 | 0.001 |

| mPcdhγB1-8 | -0.850 | 0.004 |

| rPcdhα1-12 | -0.844 | 0.005 |

| rPcdhβ3-22 | -0.850 | 0.004 |

| rPcdhγA1-12 | -0.919 | 0.0006 |

| rPcdhγB1-8 | -0.882 | 0.002 |

| DrPcdh1γ4-18 | -0.692 | 0.035 |

| DrPcdh2α8-25 | -0.936 | 0.0003 |

| DrPcdh1α3-10 | -0.657 | 0.046 |

| DrPcdh1γ19-27 | -0.790 | 0.011 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified 66 protocadherin cluster genes arrayed into two clusters in the zebrafish genome (Fig. 1). These zebrafish genes show limited orthology with mammalian protocadherin cluster genes. Nevertheless, it appears that some general features of protocadherin cluster organization are conserved among all vertebrates. For instance, zebrafish and mammalian protocadherin promoters share a highly conserved core motif (Fig. 2). We demonstrated earlier that mammalian protocadherin promoters show an increase in transcriptional activity upon neuronal differentiation in a cell-based reporter assay (Noonan et al. 2003). Because neuron-specific expression is likely to be a common feature of all protocadherin cluster genes in all vertebrates, it is not surprising that the regulatory element that confers this specificity is tightly constrained. The variable and constant exon structure and the alternatively spliced forms of each protocadherin transcript that result from this organization are apparently highly conserved as well. The mouse Pcdhα constant region has been shown to interact with the Fyn tyrosine kinase (Kohmura et al. 1998), and the Pcdhα and Pcdhγ constant region protein sequences are well conserved between zebrafish and humans. Therefore, constant region-mediated interactions with cytoplasmic signaling and structural proteins may be fundamental to protocadherin function and common to all vertebrates.

The most mutable components of protocadherin clusters among vertebrate species are the number and sequence composition of the variable exons. If protocadherin cluster proteins provide the molecular code in the development and maintenance of synaptic connections through putatively homophilic interactions across the synaptic cleft, it is the diversity among variable exon paralogs that generates combinatorial complexity in this code. In this regard, the zebrafish and mammalian protocadherin molecular codes are radically different. Although Pcdhα and Pcdhγ genes exist in both lineages and are orthologous as groups (Fig. 3; data not shown), as individual genes they are divergent. Mammals also have entire classes of protocadherin cluster genes that zebrafish apparently lack (Pcdhβ and the division of Pcdhγ into γA and γB; Wu and Maniatis 1999). The information content provided by each paralog, therefore, is lineage-specific, and the divergence of mammalian and zebrafish protocadherins could be the result of adaptive specialization of mammalian versus nonmammalian protocadherin cluster genes. This specialization would manifest in protocadherin proteins with different homophilic or heterophilic adhesive properties, resulting in lineage-specific protocadherin molecular codes in brain development.

Sequence differences among orthologous protocadherins in multiple vertebrate lineages may reflect adaptive differences in protocadherin function that contribute to lineage-specific structural and functional specializations in the brain. Although many of the fundamental regions of the brain appear to be present in all vertebrates, these regions are highly specialized within each vertebrate lineage (Striedter 1998). The result of this specialization is that homologous relationships between brain structures in divergent vertebrate species are sometimes difficult or impossible to establish. For example, the mammalian brain has a large, laminar isocortex with no obvious homolog in the brains of nonmammalian vertebrates (Nieuwenhuys et al. 1998). Protocadherins could play a role in the development of this unique structure. There are species differences in the development of particular brain structures as well. Zebrafish have a nonlaminar telencephalon that develops through a process of eversion, rather than evagination as in terrestrial vertebrates.

The divergence of zebrafish and mammalian variable exons that we observe could be due to adaptive variation erasing the phylogenetic signal between orthologs. There have also been multiple independent expansions of protocadherin genes in each lineage. Some DrPcdh1γ variable exons are clearly recent duplicates: Although they show the same patterns of homogenization as all other protocadherins, they show much less neutral paralog diversity overall (Figs. 3B,4C,6E). Because multiple, highly similar duplicates are likely to form “heterophilic” associations with each other, recent duplicates provide no additional homophilic interactions to distinguish subsets of neurons or synapses. The larger number of recent duplicates in zebrafish results in a less diverse set of protocadherins relative to mammals. This redundancy, coupled with a limited requirement for uniquely homophilic protocadherins relative to mammals, may allow zebrafish to tolerate substantial changes in protocadherin cluster gene number with no effect on fitness. However, outside of their homogenized regions, some DrPcdh1α and DrPcdh2α variable exons are divergent (Figs. 3A,6F; data not shown), indicating that they are ancient duplicates with diversified functions. Therefore, some of the zebrafish-specific expansion must provide an adaptive benefit, possibly by driving the development and function of teleost-specific neuronal pathways. Additional duplication events provide more raw material for adaptive evolution of protocadherin function, including the emergence of novel diversified paralogs, in each species.

Adaptive variation interacts with gene conversion in the process of protocadherin evolution. We have discovered clear evidence that gene conversion is common in protocadherin cluster genes. It is equally clear that some regions of protocadherin cluster genes, such as ectodomain 3, are excluded from conversion events. These regions provide most of the phylogenetic signal among mammals. Two possibilities present themselves. The first is that gene conversion events are needed to homogenize regions of each paralog class that have identical, essential yet lineage-specific functions among paralogs. In this model, ectodomain 6 mediates adhesion within each paralog subgroup, for example Pcdhβ to Pcdhβ, whereas ectodomain 3 mediates specific homophilic interactions. This is in contrast to the adhesion mechanism of classical cadherins, in which ectodomain 1 mediates homophilic interactions (Boggon et al. 2003). Gene conversion, therefore, acts to constrain protein sequence diversity. It does not matter that homogenized regions are lineage-specific, because protocadherin paralogs have to associate only with other paralogs in the same organism. In a strictly homophilic adhesion model, however, it seems that specific interactions could best be achieved by diversification among paralogs. It is possible that heterophilic associations occur in some circumstances among the members of each paralog subgroup. A definitive answer to this question awaits a rigorous examination of protocadherin adhesion.

The second possibility, which is not exclusive of the first, is that duplicated genes are prone to frequent gene conversion events, which, all else being equal, will be distributed among the duplicates according to their relative sequence similarity. Genes are homogenized within each paralog subgroup, which are more similar to each other than they are to the members of other subgroups. In zebrafish protocadherins, homogenization events also occur among genes in close physical proximity, possibly independent of any functional similarity among the proteins. Conversion events are selected against in diversified ectodomains because diversity is required in these domains for proper homophilic adhesion and to maintain the combinatorial complexity in brain development the proteins provide. These diversified domains show adaptive differences among distantly related vertebrate lineages. In this model, gene conversion events are very frequent, but are restricted to regions where protein sequence diversity is not functionally relevant. In our opinion, the data strongly support this conclusion. Diversified ectodomains are always orthologous among mouse, rat, and human, indicating that they have a precisely defined and well conserved function. A gene conversion tract that extended into a diversified ectodomain would effectively knock out that paralog and result in a duplication of the paralog contributing the donor sequence to the conversion event. A limited number of such events would probably have little deleterious effect, but their accumulation would limit the number of unique homophilic interactions available to the organism, which ultimately is disadvantageous.

In conclusion, our results indicate that protocadherin cluster genes undergo concerted evolution due to gene conversion in some parts of their coding sequences. These conversions are most likely attributable to the density of related paralogs in each cluster. Other regions, such as the core ectodomains of each molecule that provide the unique information specifying homophilic adhesion, are insulated from conversion events by selection. These regions are subject to adaptive variation among lineages, generating lineage-specific protocadherin molecular codes that contribute to differences in brain development, structure, and function among species. Lineage-specific gene duplications provide additional material for diversification of protocadherin cluster information content among vertebrate species. Therefore, the combination of lineage-specific duplication, restricted gene conversion, and adaptive variation in diversified ectodomains drives vertebrate protocadherin evolution. The expansion and adaptive evolution of large gene families, arranged both in tandem arrays and scattered throughout the genome, is a driving force in the evolution of vertebrate diversity (Ohno 1970). Several of these families, such as G-protein coupled receptors and Krüppel-type zinc finger proteins, have hundreds of genes that provide an ample reservoir for generating within- and between-species differences. Understanding the mechanisms that generate functional diversity among gene family members involved in complex systems is an essential first step toward an understanding of the molecular basis of speciation in vertebrates.

METHODS

BAC Isolation and Sequencing

We used a local implementation of TBLASTN v.2.2.5 (Altschul et al. 1997) to search the Ensembl zebrafish whole-genome shotgun trace database (http://trace.ensembl.org) for sequencing reads predicted to encode protein fragments similar to human protocadherin cluster proteins. We designed overgo probes from a subset of the high-scoring sequences we obtained and screened the CHORI-211 zebrafish BAC library (Children's Hospital of Oakland Research Institute) using standard protocols (McPherson et al. 2001). We obtained 52 BAC clones and verified these by using PCR with primers designed against the high-scoring zebrafish protocadherin trace sequences. We chose a large-insert clone with many positive PCR hits, CH211–201d21, for our initial round of sequencing. We used STS content mapping based on draft sequence from this clone and XhoI restriction digests of all positive clones to assemble a minimum tiling path. For sequencing, BAC DNA was hydrodynamically sheared with a Hydroshear Instrument (GeneMachines), size selected (3–4kb), and subcloned into the plasmid pIK96 (Stanford Human Genome Center, http://www-shgc.stanford.edu). Randomly selected plasmid subclones were sequenced in both directions with universal primers and BigDye Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems) to an average sequence depth of 10X. Sequences were then assembled and edited using the Phred/Phrap/Consed suite of programs (Ewing and Green 1998; Ewing et al. 1998; Gordon et al. 1998). Following manual inspection of the assembled sequences, finishing was performed by resequencing plasmid subclones and by walking on plasmid subclones or the large insert clone using custom primers. All finishing reactions were performed with dGTP BigDye Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems). Finished clones contain no gaps and are estimated to contain less than one error per 100,000 bp. The four BAC clones we sequenced for this study are CH211–150p19 (AC144823), CH211–201d21 (AC144828), CH211–20c7 (AC144826), and CH211–40o9 (AC146480). CH211–150p19, 201d21, and 20c7 form one contig that contains all or nearly all of one zebrafish protocadherin cluster, DrPcdh1. These clones have since been mapped to linkage group 10 by the Zebrafish Genome Fingerprinting Project (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio/WebFPC/zebra/large.shtml). CH211–40o9 maps to linkage group 14 and contains 28 additional predicted protocadherin variable exons.

Protocadherin Cluster Gene Prediction and Sequence Annotation

We used TBLASTN to identify large single-exon genes encoding proteins similar to human Pcdh variable and constant region protein sequences in our assembled BAC sequence. We also searched our assembled sequence for large open reading frames using OrfFinder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and compared the results of both methods. For the most part, the TBLASTN results were unambiguous. In cases of multiple in-frame translation start sites, we chose the translation start that resulted in a signal sequence of similar length and sequence composition as those of nearby paralogs. We used our predicted exons in TBLASTN and BLASTN searches of zebrafish ESTs from the Washington University Zebrafish Genome Resources Project (http://zfish.wustl.edu/) and from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). We obtained rat genomic sequence from the UCSC Genome Browser (Kent et al. 2002; http://genome.ucsc.edu/, June 2003 freeze) and searched for protocadherins with TBLASTN as above. We extracted, managed, and translated protocadherin exon sequences and annotated genomic sequence using custom Perl scripts.

Sequence Analysis and Phylogenetic Tree Construction

We used 351 base pairs of sequence upstream from each known and predicted translation start site of human, mouse, rat, and zebrafish Pcdh variable exons to search for conserved motifs using MEME (Bailey and Elkan 1994; http://www.meme.sdsc.edu/meme/website/intro.html). We input the core motif MEME identified into WebLogo (Schneider and Stephens 1990; http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi) to generate logograms for mammalian Pcdh, DrPcdh1, and DrPcdh2 promoters. To determine the phylogeny of full-length zebrafish and human Pcdh proteins, we removed the signal sequence from each protein and built CLUSTALW alignments (Chenna et al. 2003; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/), which we then used to estimate the maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny in SEMPHY with default parameters (Friedman et al. 2002). We used TreeEdit to draw and root each tree by midpoint (http://evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk/). We initially identified shared identical sequences among protocadherin cluster genes using GeneConv (Sawyer 1989; http://www.math.wustl.edu/~sawyer/geneconv). We identified protocadherin domains in each protein with HMMER2.2 (Durbin et al. 1998; http://hmmer.wustl.edu/) using pfamA hidden Markov model PF00028 (cadherin domain) and extracted each domain by using custom Perl scripts. We built nucleotide alignments of each ectodomain with RevTrans, a Python application that aligns coding sequences based on the protein alignment (Wernersson and Pedersen 2003; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/RevTrans/). We estimated ML gene trees in SEMPHY using the Kimura 2-parameter model of nucleotide substitution with a transition-transversion ratio of 2. We estimated synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates for each tree and average third-position GC content for each alignment by using CODEML (Yang 1997; http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software/paml.html).

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Stanford Human Genome Center Sequencing Group for their outstanding technical contributions to this project. We thank Dr. Arend Sidow for helpful comments on the manuscript, Drs. William Talbot and Marcus Feldman for providing insight and support, Christopher Brown and Gregory Cooper for excellent discussions and technical assistance, and the members of the Myers lab for discussions and support. This work was supported by the Stanford Genome Training Program (NIH training grant 5 T32 HG00044 to J.P.N.) and the NIH Centers for Excellence in Genomic Science initiative (1 P50) HG 02568-01 to R.M.M.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.2133704.

Footnotes

References

- Ahn, B.-Y., Dornfeld, K.J., Fagrelius, T.J., and Livingston, D.M. 1988. Effect of limited homology on gene conversion in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae plasmid recombination system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 2442–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amores, A., Force, A., Yan, Y.L., Joly, L., Amemiya, C., Fritz, A., Ho, R.K., Langeland, J., Prince, V., Wang, Y.L., et al. 1998. Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genome evolution. Science 282: 1711–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, T. and Elkan, C. 1994. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, pp. 28–36, AAAI Press, Menlo Park, CA. [PubMed]

- Birdsell, J.A. 2002. Integrating genomics, bioinformatics, and classical genetics to study the effects of recombination on genome evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 1181–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggon, T.J., Murray, J., Chappuis-Flament, S., Wong, E., Gumbiner, B.M., and Shapiro, L. 2003. C-cadherin ectodomain structure and implications for cell adhesion mechanisms. Science 296: 1308–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.C., and Jiricny, J. 1988. Different base/base mispairs are corrected with different efficiencies and specificities in monkey kidney cells. Cell 54: 705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck, L. and Axel, R. 1991. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: A molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell 65: 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna, R., Sugawara, H., Koike, T., Lopez, R., Gibson, T.J., Higgins, D.G., and Thompson, J.D. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3497–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin, G., Prat, F., Ell, M., and Clarke, G.D.P. 1999. Detecting and characterizing gene conversions between multigene family members. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16: 1369–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin, R., Eddy, S., Krogh, A., and Mitchison, G. 1998. Biological sequence analysis: Probabilistic models of proteins and nucleic acids Chapter 5. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Elliott, B., Richardson, C., Winderbaum, J., Nickoloff, J.A., and Jasin, M. 1998. Gene conversion tracts from double-strand break repair in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B. and Green, P. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8: 186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B., Hillier, L., Wendl, M.C., and Green, P. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8: 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker, A. 1993. Recombination and mammalian genome evolution. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 252: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch, D.H.A., Mainone, C., Goodman, M., and Slightom, J.L. 1990. Molecular history of gene conversions in the primate fetal γ-globin genes. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 781–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flajnik, M.F. 2002. Comparative analyses of immunoglobulin genes: Surprises and portents. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2: 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, N., Ninio, M., Pe'er, I., and Pupko, T. 2002. A structural EM algorithm for phylogenetic inference. J. Comput. Biol. 9: 331–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallin, W.J. 1998. Evolution of the “classical” cadherin family of cell adhesion molecules in vertebrates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15: 1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gally, J.A., and Edelman, G.M. 1992. Evidence for gene conversion in genes for cell-adhesion molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89: 3276–3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier, N. 2003. Gene conversion drives GC content evolution in mammalian histones. Trends Genet. 19: 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier, N., Piganeau, G., Mouchiroud, D., and Duret, L. 2001. GC-content evolution in mammalian genomes: The biased gene conversion hypothesis. Genetics 159: 907–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, D., Abajian, C., and Green, P. 1998. Consed: A graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, E., Broadbent, I.D., Chothia, C., and Pettitt, J. 2001. Cadherin superfamily proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. J. Mol. Biol. 305: 1011–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenbach, S., Khantane, S., Carrol, P., Gayet, O., Alonso, S., Henderson, C.E., and Dudley K. 2003. Changes in subcellular distribution of protocadherin γ proteins accompany maturation of spinal neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 72: 549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, W.J., Sugnet, C.W., Furey, T.S., Roskin, K.M., Pringle, T.H., Zahler, A.M., and Haussler, D. 2002. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12: 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohmura, N., Senzaki, K., Hamada, S., Kai, N., Yasuda, R., Watanbe, M., Ishii, H., Yasuda, M., Mishina, M., and Yagi, T. 1998. Diversity revealed by a novel family of cadherins expressed in neurons at a synaptic complex. Neuron 20: 1137–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais, G. 2003. Biased gene conversion: Implications for genome and sex evolution. Trends Genet. 19: 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, J.D., Marra, M., Hiller, L., Waterson, R.H., Chinwalla, A., Wallis, J., Sekhon, M., Wylie, K., Mardis, E.R., Wilson, K.K., et al. 2001. A physical map of the human genome. Nature 409: 934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, T., Yasunaga, T., and Nishida, T. 1980. Nucleotide sequence divergence and functional constraint in mRNA evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 77: 7328–7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, T. and Trask, B.J. 2003. Complex evolution of 7E olfactory receptor genes in segmental duplications. Genome Res. 13: 781–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M., Gu, X., and Sitnikova, T. 1997. Evolution by the birth-and-death process in multigene families of the vertebrate immune system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 7799–7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys, R., Ten Donkelaar, H.J., and Nicholson, C. 1998. The central nervous system of vertebrates. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg.

- Noonan, J.P., Li, J., Nguyen, L., Caoile, C., Dickson, M., Grimwood, J., Schmutz, J., Feldman, M.W., and Myers, R.M. 2003. Extensive linkage disequilibrium, a common 16.7 kilobase deletion, and evidence of balancing selection in the human protocadherin α cluster. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72: 621–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata, S., Sago, H., Mori, N., Rochelle, J.M., Seldin, M.F., Davidson, M., St. John, T., Taketani, S., and Suzuki, S.T. 1995. Protocadherin Pcdh2 shows properties similar to, but distinct from, those of classical cadherins. J. Cell Sci. 108: 3765–3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, S. 1970. Evolution by gene duplication. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- Ohta, T. 1980. Evolution and variation of multigene families. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- Phillips, G.R., Tanaka, H., Frank, M., Elste, A., Fidler, L., Benson, D.L., and Colman, D.R. 2003. Gamma-protocadherins are targeted to subsets of synapses and intracellular organelles in neurons. J. Neurosci. 23: 5096–5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S.A. 1989. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol. Biol. Evol. 6: 526–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, T.D. and Stephens, R.M. 1990. Sequence logos: A new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 6097–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senzaki, K., Ogawa, M., and Yagi, T. 1999. Proteins of the CNR family are multiple receptors for reelin. Cell 99: 635–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, D., Glusman, G., Pilpel, Y., Khen, M., Gruetzner, F., Haaf, T., and Lancet, D. 1999. Primate evolution of an olfactory receptor gene cluster: Diversification by gene conversion and recent emergence of pseudogenes. Genomics 61: 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slightom, J.L., Blechi, A.E., and Smithies, O. 1980. Human fetal Gγ- and Aγ-globin genes: Complete nucleotide sequences suggest that DNA can be exchanged between these duplicated genes. Cell 21: 627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.P. 1974. Unequal crossover and the evolution of muligene families. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 38: 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.G.C. and Eyre-Walker, A. 2001. Synonymous codon bias is not caused by mutation bias in G+C-rich genes in humans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 982–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striedter, G.F. 1998. Progress in the study of brain evolution: From speculative theories to testable hypotheses. Anat. Rec. (New Anat.) 253: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, N., Paques, F., Colaiacovo, M., and Haber J.E. 1997. Role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2 and Msh3 repair proteins in double-strand break-induced recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 9214–9219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasic, B., Nabholz, C.E., Baldwin, K.K., Kim, Y., Rueckert, E.H., Ribich, S.A., Cramer, P., Wu, Q., Axel, R., and Maniatis, T. 2002. Promoter choice determines splice site selection in protocadherin α and γ pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 10: 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Su, H., and Bradley, A. 2002a. Molecular mechanisms governing Pcdh-γ gene expression: Evidence for a multiple promoter and cis-alternative splicing model. Genes & Dev. 16: 1890–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Weiner, J.A., Levi, S., Craig, A.M., Bradley, A., and Sanes, J.R. 2002b. Gamma protocadherins are required for survival of spinal interneurons. Neuron 36: 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernersson, R. and Pederson, A.G. 2003. RevTrans—Constructing alignments of coding DNA from aligned amino acid sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3537–3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q. and Maniatis, T. 1999. A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell 97: 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q., Zhang, T., Cheng, J.F., Kim, Y., Grimwood, J., Schmutz, J., Dickson, M., Noonan, J.P., Zhang, M.Q., Myers, R.M., et al. 2001. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of mouse and human protocadherin clusters. Genome Res. 11: 389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. 1997. PAML: A program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13: 555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://hmmer.wustl.edu/; HMMER.

- http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software/paml.html; PAML.

- http://www.math.wustl.edu/~sawyer/geneconv; GeneConv.

- http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/RevTrans/; RevTrans.

- http://genome.ucsc.edu/; UCSC Genome Browser.

- http://home.clara.net/sisa/; Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis.

- http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi; WebLogo.

- http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/website/intro.html; MEME.

- http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio/WebFPC/zebra/large.shtml; Zebrafish Genome Fingerprinting Project.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; GenBank and OrfFinder.

- http://zfish.wustl.edu/; Washington University Zebrafish Genome Resources Project.

- http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/; CLUSTALW.

- http://trace.ensembl.org/; Ensembl Trace Database.

- http://www-shgc.stanford.edu; Stanford Human Genome Center.

- http://www-shgc.stanford.edu/myerslab/; Myers Lab.

- http://evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk/; TreeEdit.