Abstract

Cyclopropane-substituted allylic ethers react with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone to form oxocarbenium ions with no competitive ring cleavage. This reaction can be used for the preparation of cyclopropane-substituted tetrahydropyrans. The protocol was used as a key step in the total synthesis of the sponge-derived macrolide clavosolide A.

The strain energy of approximately 27 kcal/mol in cyclopropanes provides a driving force for several ring-opening reactions that are not observed in less strained cycloalkanes.1 Cyclopropane cleavage is commonly encountered when a reactive intermediate such as a carbenium ion is introduced on an adjacent atom.2 These ring cleavage processes limit the reaction conditions that can be utilized in the presence of cyclopropanes and often mandate that the synthesis of cyclopropane-containing products employ cyclopropanation reactions at a late stage in the sequence.

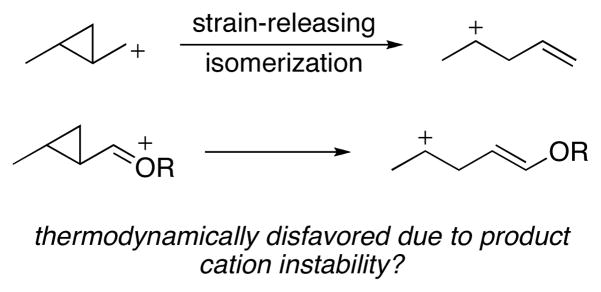

Cationic cyclopropane-opening reactions can be suppressed by sufficiently stabilizing the reactive intermediate to counterbalance the energetic benefit of strain release.3 This is illustrated in Scheme 1, whereby the cleavage of a cyclopropane with an adjacent oxocarbenium ion is postulated to be disfavored because the product contains a far less stabilized cation in comparison to the starting material. Indeed Taylor and co-workers have demonstrated4 that cyclopropanes can be formed from intramolecular additions of electron rich alkenes into cationic intermediates, a process that is the microscopic reverse of cation-induced cyclopropane opening.

Scheme 1.

Energetics of cyclopropyl carbinyl cation ring opening.

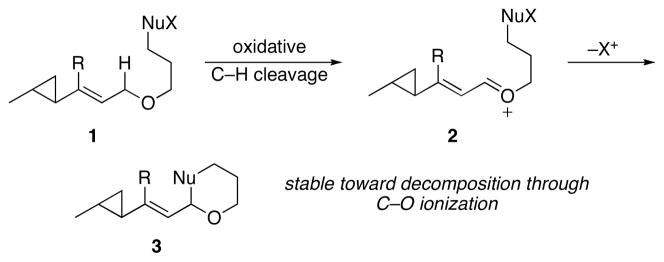

The stability of cyclopropane-substituted oxocarbenium ions creates opportunities for functionalization through nucleophilic addition reactions. The products of these additions, however, would still be susceptible to cyclopropane opening through ionization of the product alkoxy group if classical Lewis acid-mediated protocols are employed for oxocarbenium ion generation. This suggests that electrophile formation under non-acidic conditions would provide strategic benefits for the functionalization of cyclopropane-containing molecules. Oxidative carbocation formation provides an alternative to Lewis acid-mediated ionization and has been used in the synthesis of complex structures that contain sensitive groups such as acetals and epoxides.5 We have been engaged in developing oxidative carbon–hydrogen bond cleavage reactions to generate stabilized carbocations under non-acidic conditions.6 These processes proceed through reactions of allylic, benzylic, and vinylic ethers, amides, and sulfides with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ). In this manuscript we report that cyclopropane-substituted α,β-unsaturated oxocarbenium ions can be prepared through allylic ether oxidation and that the resulting intermediates can be trapped to form tetrahydropyrans with no evidence of ring opening, as shown in the generic conversion of 1 to 2 to 3 in Scheme 2. This process is used as the key step in a convergent synthesis of the macrodiolide clavosolide A.

Scheme 2.

Oxidative synthesis of cyclopropane-containing tetrahydropyrans.

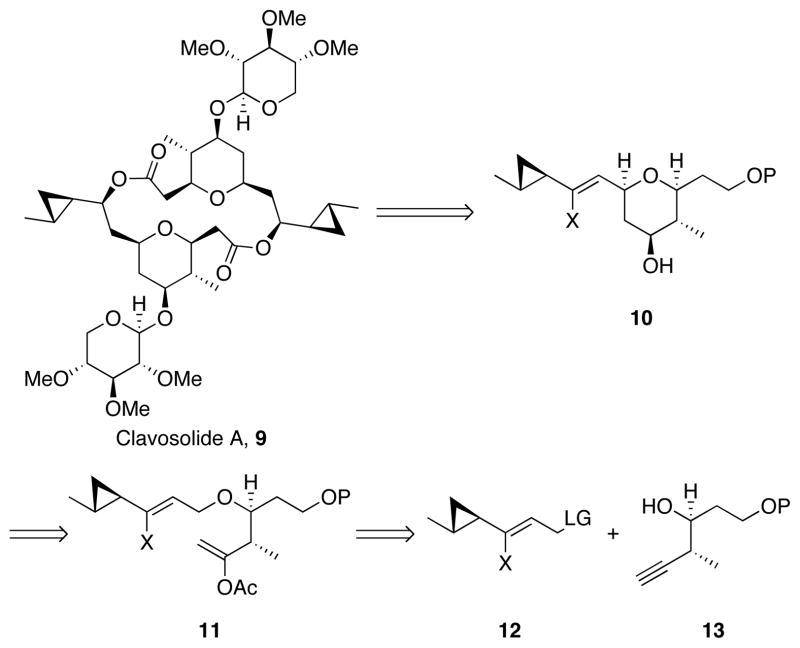

The initial demonstrations of this transformation are shown in Scheme 3. Vinylsilanes were selected as substrates because they can be converted stereoselectively to secondary alcohols through a short sequence6d and they are readily accessed with high geometric control from alkynes through hydrosilylation reactions7 with ruthenium or platinum catalysts. Enol acetates were used as the nucleophiles because they are oxidatively stable enolate surrogates. Exposing Z-vinylsilane 4 to DDQ at 45 °C provided oxocarbenium ion 5 en route to the formation of tetrahydropyrone 6. While many DDQ-mediated oxocarbenium ion formations proceed at ambient temperature or below, the vinylsilanes generally require higher temperatures because steric bulk interferes with their association with the oxidant.5d The oxidation of (E)-isomer 7 proceeds with similar efficiency to form 8. These reactions provided inseparable diastereomeric mixtures of products, showing that the cyclopropyl group does not promote remote stereoinduction. While the yields of these reactions were not quantitative, the remainder of the mass can be attributed to non-specific decomposition pathways rather than cyclopropane ring-opening. These results provided a suitable precedent for the application of the protocol in a more complex setting.

Scheme 3.

Oxidative cyclization of cyclopropane-containing substrates.

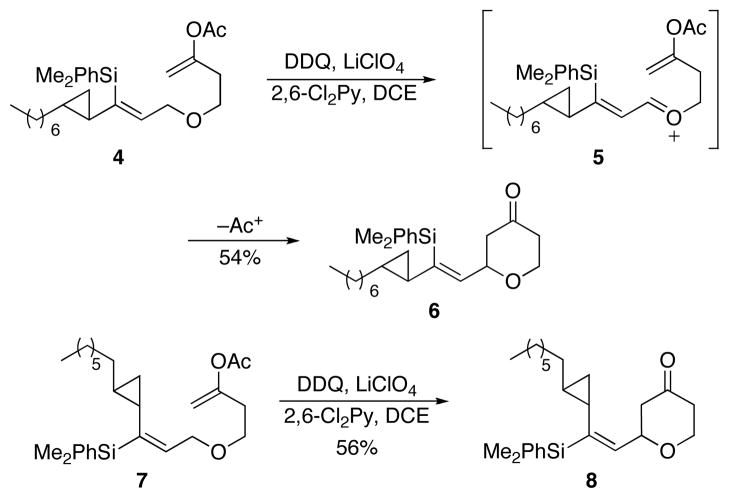

We chose clavosolide A, 9 (Scheme 4) as a target to highlight the utility of the protocol. The Faulkner group isolated clavosolide A from a sponge off the coast of the Phillipines8 but limited quantities have precluded a thorough examination of its biological activity. A revision of the stereostructure was proposed by Willis9 and was confirmed through a total synthesis from the Lee group.10 Several total and formal syntheses of clavosolide A have subsequently been reported,11 with the majority employing a late stage introduction of the cyclopropyl group to avoid the potential for ring opening. Smith and co-workers introduced the cyclopropane at an early stage but noted the Lewis acid sensitivity of the group, and cautioned against prolonged reaction times and the use of strong acids.11b Our objective was to demonstrate that the oxidative cyclization conditions allow the cyclopropane unit of clavosolide A to be introduced at an early stage in the synthesis, thereby providing an attractive strategy for a convergent synthesis. We envisioned 9 as arising from cyclopropyl tetrahydropyran 10, which can be accessed from ether 11 through an oxidative cyclization. This ether can arise from the union of subunits 12 and 13.

Scheme 4.

Retrosynthetic analysis of clavosolide A.

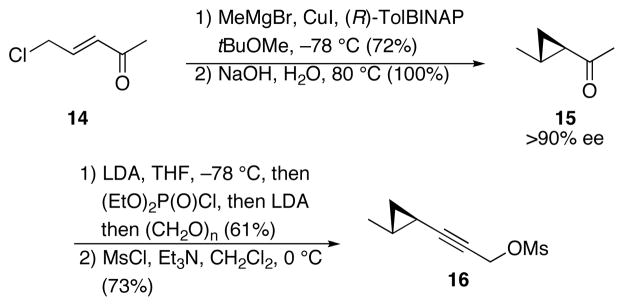

The synthesis of the cyclopropane-containing subunit (Scheme 5) employed Feringa’s elegant asymmetric 1,4-addition protocol12 as the key step. Conjugate addition of MeMgBr to chloro enone 14, prepared in one step from allyl chloride and acetyl chloride,13 in the presence of CuI and (R)-tolylBINAP provided a chloro enolate that could either be warmed to generate cyclopropane 15 directly or quenched at low temperature and subjected to base to effect the cyclopropanation in >90% ee.14 We found that the yield and reproducibility were superior for the two step protocol. The methyl ketone was converted to a propargyl alcohol through Negishi’s method15 in which the enolate was quenched with diethylphosphoryl chloride and the resulting phosphonate was subjected to excess LDA to generate the alkynyl anion. Quenching the alkynyl anion with paraformaldehyde completed the construction of the propargyl alcohol. Converting the hydroxy group to a leaving group proved to be challenging due to cyclopropane-opening upon exposure to common halogenating agents. However mesylation under standard conditions could be achieved to form 16. This species should be prepared shortly before the subsequent step due to its propensity for ionization and decomposition.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of the cyclopropane-containing subunit.

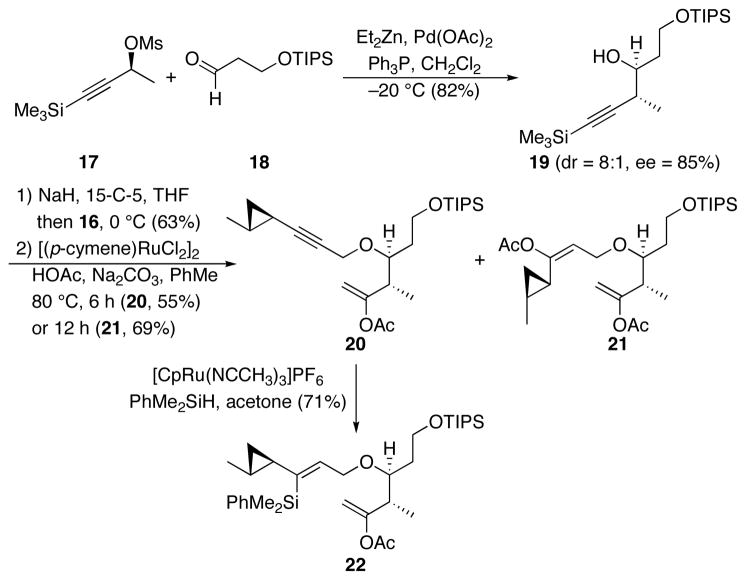

The synthesis of the cyclization precursor is shown in Scheme 6. Coupling mesylate 17, in which the stereocenter can be conveniently prepared through a Noyori reduction,16 with aldehyde 18 under Marshall’s conditions17 provided homopropargylic alcohol 19 with good enantio- and diastereocontrol. Deprotonation followed by the addition of mesylate 16 under modified Williamson conditions18 provided the expected ether with concomitant cleavage of the alkynylsilane group. The addition of HOAc through standard ruthenium-catalyzed conditions19 provided a mixture of the expected enol acetate 20 (55%) and di-enol acetate 21 (27%). This procedure is generally quite selective for terminal alkynes in preference to internal alkynes,6d,h indicating that the cyclopropane group plays an activating role. The cis-addition across the internal alkyne was confirmed through NOESY experiments on a subsequent intermediate. Subjecting 20 to hydrosilylation under Trost’s conditions20 provided vinylsilane 22 in 71% yield. Since 21 could in principle also suffice for our synthetic objectives, we exposed the di-yne to higher catalyst loading and a longer reaction time to provide the di-addition product in 69% yield.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the cyclization substrates.

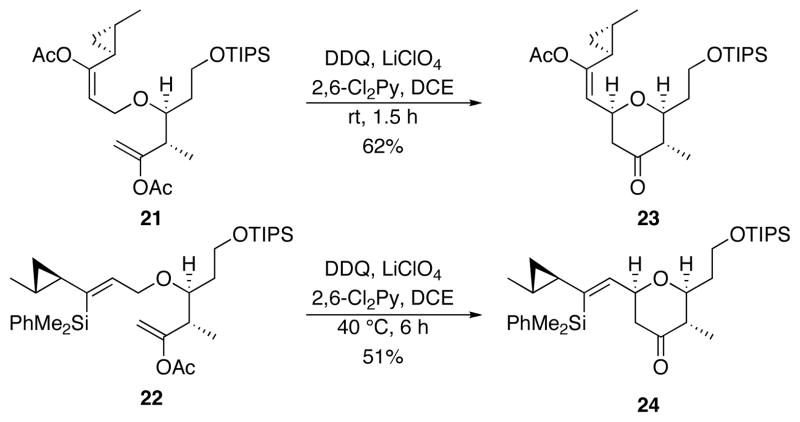

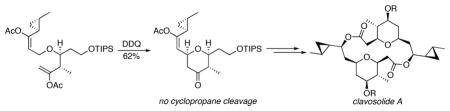

The oxidative cyclization reactions are shown in Scheme 7. Exposing 21 to DDQ at rt for 1.5 h provided 23 as a single stereoisomer in 62% yield. The cyclization of 22 required heating to 40 °C for 6 h to provide a 51% yield of 24. No attempt was made to optimize the yield for the cyclization of 22 in consideration of material accessibility and the superiority of 21 as a substrate. The cyclization of 21 is significant in that it highlights the utility of enol acetates as stabilizing groups for oxidative carbocation formation, thereby providing an additional option for the formation of functionalized alkenyl tetrahydropyrans that can be used for subsequent diversification studies.

Scheme 7.

Comparison of oxidative cyclization substrates.

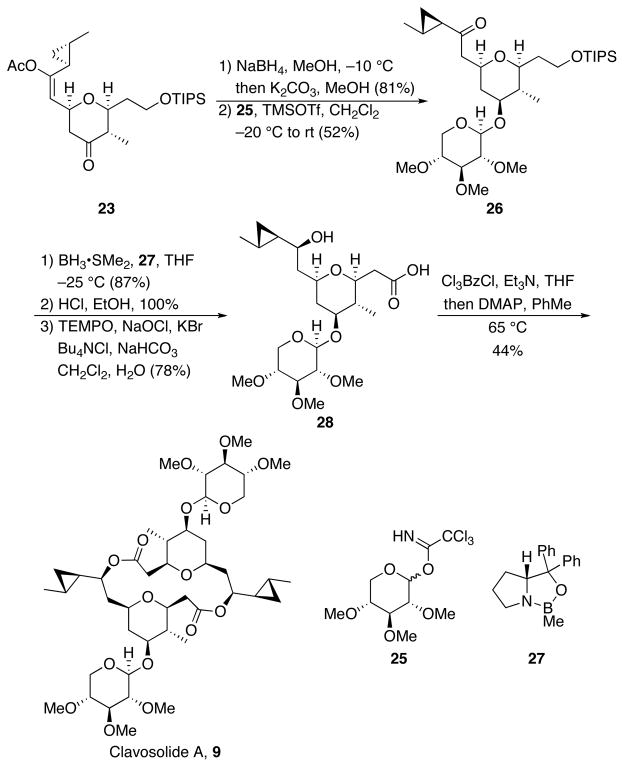

The completion of the synthesis is shown in Scheme 8. Ketone reduction of 23 with NaBH4 smoothly provided the equatorial alcohol on the tetrahydropyran. The enol acetate was then cleaved with K2CO3 and MeOH to yield the corresponding ketone. Glycosidation was conducted at this point in accord with syntheses of related structures,10c,21 because the glycosyl group can effectively serve as a hydroxyl protecting group. Additonally, three anomeric stereoisomers can form if glycosidation is conducted after macrodiolide formation, resulting in a low product yield and a significant separation problem if the glycosylation reaction shows poor selectivity. Adding the tetrahydropyranol to trichloroacetimidate 259 in the presence of TMSOTf provided glycoside 26 (52%) along with significant amounts of its anomer. The reduction of a similar ketone group has been reported9c to proceed with useful substrate-directed stereocontrol, but we found superior results could be attained through reagent-directed stereocontrol. Exposing 26 to BH3•SMe2 and catalyst 2722 provided the desired secondary alcohol in high yield and with good diastereocontrol. Removal of the silyl protecting group was achieved with HCl in EtOH. Selective oxidation of the primary alcohol23 yielded carboxylic acid monomer 28. Macrodiolide formation under Yamaguchi’s conditions24 completed the synthesis of clavosolide A.

Scheme 8.

Completion of the synthesis.

We have shown that cyclopropanes are compatible with oxocarbenium ion formation through carbon–hydrogen bond oxidation and have applied this result to the synthesis of cyclopropane-substituted tetrahydropyrans. The functional group tolerance of the oxidative cyclization allowed for a convergent total synthesis of clavosolide A. Key steps in the sequence include an early stage Feringa asymmetric cyclopropanation reaction and the oxidation of of an acetoxy-substituted allylic ether as a precursor to a functionalized unsaturated oxocarbenium ion. The capacity to introduce cyclopropane groups at an early stage of a synthetic sequence that eventually proceeds through a carbocation-forming reaction adds to the unique strategic options that oxidative carbon–hydrogen bond functionalization offers for complex molecule synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM062924) for generous support of this work. We thank Professor T. K. Chakraborty and Dr R. Reddy Vakiti (Central Drug institute, Lucknow, India) for helpful discussions and sharing spectra.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures for cyclization reactions and characterization data for all new compounds. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.de Meijere A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1979;18:809. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Hanack M, Schneider HJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1967;6:666. [Google Scholar]; (b) Olah GA, Jeull CL, Kelly DP, Porter RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:146. [Google Scholar]; (c) Saunders M, Laidig KE, Wiberg KB, Schleyer PvR. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7652. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olah GA, Reddy VP, Prakash GKS. Chem Rev. 1992;92:69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Taylor RE, Engelhardt FC, Schmitt MJ, Yuan H. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2964. [Google Scholar]; (b) Risatti CA, Taylor RE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6671. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Wan S, Gunaydin H, Houk KN, Floreancig PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7915. doi: 10.1021/ja0709674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Green ME, Rech JC, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:7317. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Clausen DJ, Wan S, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:5178. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Tu W, Liu L, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:4184. doi: 10.1002/anie.200706002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tu W, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:4567. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu L, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2009;11:3152. doi: 10.1021/ol901188q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu L, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:3069. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu L, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:5894. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Brizgys GJ, Jung HH, Floreancig PE. Chem Sci. 2012;3:438. [Google Scholar]; (g) Cui Y, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2012;14:1720. doi: 10.1021/ol3002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Han X, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2012;14:3808. doi: 10.1021/ol301720u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Clausen DJ, Floreancig PE. J Org Chem. 2012;77:6574. doi: 10.1021/jo301185h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim DSW, Anderson EA. Synthesis. 2012;44:983. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao MR, Faulkner DJ. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:386. doi: 10.1021/np010495l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry CS, Bushby N, Charmant JPH, Elsworth JD, Harding JR, Willis CL. Chem Commun. 2005:5097. doi: 10.1039/b509757f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Son JB, Kim SN, Kim NY, Lee DH. Org Lett. 2006;8:661. doi: 10.1021/ol052851n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Barry CS, Elsworth JD, Seden PT, Bushby N, Harding JR, Alder RW, Willis CL. Org Lett. 2006;8:3319. doi: 10.1021/ol0611705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith AB, III, Simov V. Org Lett. 2006;8:3315. doi: 10.1021/ol0611752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chakraborty TK, Reddy VR, Gajula PK. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:5162. [Google Scholar]; (d) Carrick JD, Jennings MP. Org Lett. 2009;11:769. doi: 10.1021/ol8028302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Hartog T, Rudolph A, Maciá B, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14349. doi: 10.1021/ja105704m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulinkovich OG, Tischenko IG, Sorokin VL. Synthesis. 1985:1058. [Google Scholar]

- 14.An exact value for the ee could not be obtained because of overlapping peaks in the HPLC trace. Please see the Supporting Information for details.

- 15.Negishi E, King AO, Klima WL, Patterson W, Silveira A., Jr J Org Chem. 1980;45:2526. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumura K, Hashiguchi S, Ikariya T, Noyori R. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8738. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall JA, Adams ND. J Org Chem. 1998;63:3812. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aspinall HC, Greeves N, Lee WM, McGiver EG, Smith PM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:4679. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goossen LJ, Paetzold J, Koley D. Chem Commun. 2003:706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trost BM, Ball ZT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17644. doi: 10.1021/ja0528580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Kim H, Hong J. Org Lett. 2010;12:2880. doi: 10.1021/ol101022z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Seden PT, Charmant JPH, Willis CL. Org Lett. 2008;10:1637. doi: 10.1021/ol800386d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9153. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1986. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anelli PL, Biffi C, Montanari F, Quici S. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2559. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katzuki T, Yamaguchi M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1979;52:1989. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.