Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a recently recognized, immune-mediated disease characterized clinically by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation. The chronic esophageal eosinophilia of EoE is associated with tissue remodeling that includes epithelial hyperplasia, subepithelial fibrosis, and hypertrophy of esophageal smooth muscle. This remodeling causes the esophageal rings and strictures that frequently complicate EoE and underlies the mucosal fragility that predisposes to painful mucosal tears in the EoE esophagus. The pathogenesis of tissue remodeling in EoE is not completely understood, but emerging studies suggest that secretory products of eosinophils and mast cells, as well as cytokines produced by other inflammatory cells, epithelial cells, and stromal cells in the esophagus, all contribute to the process. Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, Th2 cytokines overproduced in allergic disorders, have direct profibrotic and remodeling effects in EoE. The EoE esophagus exhibits increased expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, which is a potent activator of fibroblasts and a strong inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. In addition, IL-4, IL-13, and TGF-β all have a role in regulating periostin, an extracellular matrix protein that might influence remodeling by acting as a ligand for integrins, by its effects on eosinophils or by activating fibrogenic genes in the esophagus. Presently, few treatments have been shown to affect the tissue remodeling that causes EoE complications. This report reviews the potential roles of fibroblasts, eosinophils, mast cells, and profibrotic cytokines in esophageal remodeling in EoE and identifies potential targets for future therapies that might prevent EoE complications.

Keywords: subepithelial fibrosis, transforming growth factor- β, interleukin-13, interleukin-4, periostin

eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) recently has been defined as a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation (89). EoE affects both children and adults of all ages and of all racial and ethnic groups, and EoE can severely impair the quality of life. The first report describing EoE as a distinct clinicopathological disorder was published in 1993 (14), and the incidence of this disorder has increased dramatically ever since.

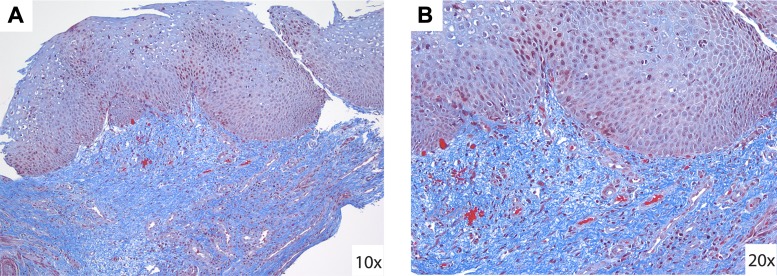

In EoE, food and aeroallergens appear to activate a Th2 immune response, resulting in the production of Th2 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-13 and IL-4 (142, 147). These cytokines stimulate the esophagus to express eotaxin-3, a potent eosinophil chemoattractant thought to play a key role in drawing eosinophils to the esophagus in EoE (18, 19). Esophageal epithelial injury results from the release of toxic eosinophil degranulation products. Prolonged eosinophil-predominant inflammation also can result in tissue remodeling characterized by hyperplasia of the epithelium, subepithelial fibrosis (Fig. 1), angiogenesis, and hypertrophy of esophageal smooth muscle (3, 4, 7, 93, 103, 107, 120, 126, 148, 171). This remodeling can cause serious complications including esophageal ring and stricture formation, which are responsible for the dysphagia and episodes of food impaction typical of EoE (45, 135, 141). Tissue remodeling also can result in esophageal dysmotility, which might contribute to the dysphagia and chest pain of EoE, and in fragility of the esophageal mucosa, which predisposes to painful mucosal tears that can occur spontaneously or with instrumentation of the esophagus.

Fig. 1.

Subepithelial fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis. Masson trichrome stain of an esophageal mucosal biopsy specimen from a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) demonstrating extensive subepithelial fibrosis in ×10 (A) and ×20 (B) magnifications. Photomicrographs provided by Dr. Robert Genta.

The study of tissue remodeling in EoE is especially challenging because the process largely involves the deep layers of the esophageal mucosa, as well as the submucosa and muscularis propria, and techniques for sampling and imaging these layers with microscopic precision are limited. Typical endoscopic biopsies of the esophageal mucosa are usually limited to just the epithelium. In a recent study in which the investigators evaluated the depth of 1,692 endoscopic esophageal biopsy tissue pieces (53), for example, fewer than 11% were found to contain subepithelial lamina propria. Thus the large majority of endoscopic biopsy specimens provide little information on tissue remodeling, and very few full-thickness esophageal specimens from patients with EoE have been available for study.

The pathogenesis of tissue remodeling in EoE is not completely understood, but studies suggest that secretory products of eosinophils and mast cells, as well as cytokines produced by inflammatory cells, epithelial cells, and stromal cells in the esophagus (e.g., IL-13, IL-4, IL-5, eotaxin-3, periostin, and TGF-β), all contribute to the process. Available treatments for EoE are aimed primarily at decreasing the number of esophageal eosinophils, and few treatments target cytokines specifically. The goals of treatment are the relief of symptoms and the prevention of EoE complications. A number of studies have established the efficacy of various treatments in relieving EoE symptoms and decreasing esophageal eosinophilia (52, 69, 76, 78, 90, 96, 134, 138–140), but few studies have been designed to address the treatment and prevention of the tissue remodeling that causes EoE complications. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying tissue remodeling might identify novel therapeutic targets that could be used to prevent the serious consequences of EoE. This report reviews some key features of fibrosis, discusses the role of eosinophils and mast cells in fibrogenesis, summarizes the main cytokine mediators of fibrosis, and highlights the fibrogenic role of periostin in the extracellular matrix in EoE.

Fibroblasts and Fibrogenesis

Fibrogenesis (the development of fibrous tissue) is part of the normal repair process triggered by epithelial injury. Injured epithelial cells and infiltrating immune cells release mediators that can initiate and regulate fibrogenesis. Profibrotic cytokines like IL-13 and profibrotic growth factors, such as TGF-β and platelet-derived growth factor, can activate quiescent fibroblasts to transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts. These myofibroblasts play key roles in the synthesis, deposition, organization, and degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins including collagen, fibronectin, tenascin-C, periostin, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Myofibroblasts have features of both fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells, as they express large amounts of vimentin, an intermediate filament protein typically expressed by fibroblasts, as well as α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a microfilament protein characteristic of smooth muscle cells. By virtue of their contractile phenotype, myofibroblasts can cause wound contraction.

Myofibroblasts typically are derived from local fibroblasts in the mesenchyme of the injured tissue. In some circumstances, however, fibrocytes can be recruited from the bone marrow through the blood to peripheral sites of injury, where those inactive fibrocytes differentiate into active fibroblasts (44). Recent studies also suggest that fibroblasts can be derived directly from epithelial and endothelial cells through the processes of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (70) and EMT (124), respectively. Thus epithelial and endothelial cells can actively contribute to tissue remodeling with fibrogenesis. Although limited fibrogenesis is a normal response to tissue injury, severe injury or chronic inflammation can cause the deposition of large quantities of ECM protein and the excess matrix contraction that characterize fibrosis. Extensive subepithelial fibrosis often is observed in the esophagus of adult (107, 120, 148) and pediatric patients (7, 28) with EoE.

Eosinophils and Mast Cells

Both eosinophils and mast cells infiltrate the esophagus in EoE, and both are considered major effector cells of tissue fibrosis and remodeling (74, 86, 117). There are complex interactions among eosinophils, mast cells, fibroblasts, and other cell types that might influence tissue remodeling in the esophagus. Eosinophils and mast cells release a wide array of biologically active cytokines that can regulate fibroblast function. Conversely, fibroblasts can regulate the function of eosinophils and mast cells (84–86, 158), and eosinophils and mast cells can affect each other's activation, signal trafficking, and proliferation (88, 110, 116, 121, 161). In addition, eosinophil- and mast cell-derived proteins can cause epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells to produce substances that also can regulate tissue remodeling.

There is abundant evidence supporting the role of eosinophils in the fibrosis and airway remodeling that occurs in asthma (73). Studies in asthma and other fibrotic disorders have implicated a number of eosinophil protein products, including TGF-β, IL-13, IL-4, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiogenin, IL-8, and major basic protein (MBP), in the regulation of tissue remodeling (Table 1) (61, 62, 74). Angiogenic eosinophil products such as VEGF, angiogenin, and IL-8 recently have been identified in greater levels in esophageal mucosal biopsies from patients with EoE than from control patients (122). In esophageal epithelial cells, MBP has been shown to induce the production of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)9, which promotes cell proliferation, and high levels of FGF9 have been found in esophageal biopsy specimens from patients with EoE (108).

Table 1.

Eosinophil- and/or mast cell-derived proteins involved in tissue remodeling

| Mediator | Eosinophil-Derived | Mast Cell-Derived | Fibrosis (Fibroblast Activation and Proliferation) | Epithelial Hyperplasia (Epithelial Cell Activation and Proliferation) | Smooth Muscle Hypertrophy and Contraction (Smooth muscle cell Activation and Proliferation) | Angiogenesis (Endothelial Cell Activation and Proliferation) | ECM Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β (23, 68, 113, 159) | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| TGF-α (21, 57, 156) | + | + | + | + | |||

| TNF-α (24, 95, 113, 155) | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| VEGF (113, 122) | + | + | + | ||||

| FGF-2 (16, 22, 113, 149) | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| PDGF (16, 36, 113) | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| EGF (10, 16, 23, 127) | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| NGF (101, 112) | + | + | + | + | |||

| IL-4 (9, 125, 151) | + | + | + | + | |||

| IL-6 (50, 150) | + | + | + | + | |||

| IL-8 (113) | + | + | + | ||||

| IL-13 (17, 21, 92, 105, 151) | + | + | + | + | |||

| MMP-9 (71, 115) | + | + | + | ||||

| Angiogenin (122) | + | + | |||||

| MBP (66, 108, 132) | + | + | + | + | |||

| Chymase (82, 129) | + | + | + | + | |||

| Tryptase (26, 49, 129, 163) | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Histamine (5, 58) | + | + | + | ||||

| Heparin (49) | + | + |

Eosinophils and mast cells express numerous cytokines and chemokines that may participate in tissue remodeling. These proteins can target fibroblasts, epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells to induce potential effects such as fibrosis, epithelial hyperplasia, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and angiogenesis.

TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; PDGF, platelet derived growth factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; MBP, major basic protein.

Immunohistochemical staining has revealed increased numbers of mast cells in the esophagus of patients with EoE, and elevated esophageal levels of mast cell genes such as carboxypeptidase A3, tryptase, histidine decarboxylase, and FcϵRI have been documented as well (1, 5, 19, 64, 142). However, the precise distribution of these mast cells in the layers of the esophageal wall is not clear, largely because few full-thickness esophageal specimens from patients with EoE have been available for examination. Studies of esophageal biopsy specimens from patients with EoE have revealed mast cells in the epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae (1, 5, 142). A report of a patient with idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis who had an esophagectomy described mast cells in the muscularis propria as well (111).

Mast cell activation (with degranulation and mediator release) can be initiated by a number of factors including cross-linking of IgE antibodies, stem cell factor, complement fragments, neuropeptides, adenosine, bacteria cell wall components, eosinophil-derived proteins, acid reflux, and bile reflux (162). The specific mast cell proteins released depend in part on the factors that initiate mast cell activation. Mast cells and eosinophils share a number of the same protein products (Table 1). However, some mast cell-specific proteins such as histamine, tryptase, and chymase are known to be involved in smooth muscle contraction and hypertrophy (5, 26, 117). The observation that mast cells are found in the muscle layers of the esophagus in EoE suggests that mast cells might contribute to the smooth muscle hypertrophy and dysmotility that occurs in this disorder (5).

As shown in Table 1, there are numerous eosinophil- and mast cell-derived cytokines and chemokines with the potential to participate in tissue remodeling in EoE. Furthermore, other cell types also may express some of these molecules. For example, Straumann et al. (142) have demonstrated that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α is highly expressed by epithelial cells in EoE. It is not clear whether TNF-α exerts direct profibrotic effects, but studies on Crohn's disease (155) and pulmonary fibrosis (119) have suggested that TNF-α might contribute to fibrosis by upregulating tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease (TIMP)-1, which can increase collagen accumulation. Furthermore, angiogenic effects have been described for TNF-α (168), and activation of the TNF-α-NF-κB pathway has been implicated as a cause for angiogenic remodeling in EoE (122).

TGF-β

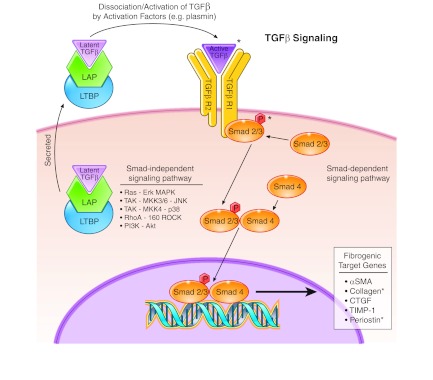

TGF-β is a multifunctional cytokine that clearly plays a key role in fibrosis and has been extensively studied in a number of fibrotic diseases (166). Although there are three isotypes of TGF-β, tissue fibrosis is associated primarily with the TGF-β1 isoform produced in large part by monocytes and macrophages, but also by eosinophils and mast cells. TGF-β is synthesized and secreted as part of a large latent complex in which it is bound to a latency-associated protein (LAP) in a complex with a latent-TGF-β-binding protein (LTBP) (8). TGF-β remains inactive in this complex, and dissociation of the LAP and LTBP renders TGF-β active. This dissociation and activation is induced by a number of agents such as plasmin, thrombospondin-1, integrins, MMPs, reactive oxygen species, and acid (8, 109). The activated TGF-β binds its receptors (TGF-βR1 and TGF-βR2) and exerts its effects via both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways (Fig. 2) (32).

Fig. 2.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway. TGF-β is a pleiotropic cytokine that mediates fibrosis by inducing fibrogenic target genes. TGF-β is generally secreted as part of a large latent complex bound to latency-associated protein (LAP) and latent-TGF-β-binding protein (LTBP). Latent TGF-β is activated when it dissociates from LAP and LTBP. The active TGF-β binds its receptor to initiate Smad-dependent and independent signaling. Smad-dependent signaling regulates fibrogenic target genes such as α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), collagen, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease (TIMP-1), and periostin. TGF-β can also induce a number of Smad-independent pathways such as Ras, TGF-β-activated kinase (TAK), RhoA, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), thereby adding to its pleiotropic effects. *Protein has been linked to EoE.

Smad proteins are a family of transcription factors that mediate TGF-β signals. In Smad-dependent signaling, TGF-βR1 is responsible for phosphorylating receptor-regulated Smads such as Smad2 and 3. Once phosphorylated, they form a complex with common Smad4. This complex then translocates into the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of fibrogenic target genes such as α-SMA, collagen, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), TIMP-1, and periostin (36, 152, 159). Independent of the Smads, TGF-β can activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways including Ras-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk), TGF-β-activated kinase (TAK)-MAP kinase kinase (MKK)3/6-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, and TAK-MKK4-p38. Additional Smad-independent pathways activated by TGF-β include RhoA and its effector kinase p160 ROCK, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and its effector Akt. Smad-independent pathways have not been examined in EoE, and we will not review these pathways further.

A number of studies have documented increased expression of TGF-β1 in the esophagus of patients with EoE (5–7, 103, 146). In EoE esophageal biopsy specimens, Aceves et al. (7) found increased expression of TGF-β1 in the lamina propria and increased levels of pSMAD2/3 in the lamina propria and basal epithelial cells, suggesting mesenchymal-epithelial signaling in this process; corresponding trichrome stains revealed copious subepithelial fibrosis in those biopsy specimens.

The predominant cellular source of TGF-β1 in EoE is not clear and may vary with the layer of the esophageal wall. In the lamina propria, for example, TGF-β1 is found largely in eosinophils (7), whereas mast cells appear to be the predominant producers of TGF-β1 in the muscularis mucosae (5). It is also possible that T cells contribute to TGF-β1 production in EoE.

TGF-β1 is both a potent activator of fibroblasts and a strong inducer of EMT, the process whereby epithelial cells assume morphological and phenotypical properties of fibroblasts (70). Recently, Kagalwalla et al. (68) found evidence of EMT by immunostaining for vimentin (an intermediate filament protein expressed by mesenchymal cells) and cytokeratins (proteins of keratin-containing intermediate filaments expressed by epithelial cells) in esophageal mucosal biopsies from patients with EoE. They observed that the degree of EMT correlated with the fibrosis score (r = 0.644) and with TGF-β1 immunostaining (r = 0.520) and that EMT decreased significantly when patients were treated with elemental and elimination diets or with topical steroid therapy. Using the HET-1A esophageal epithelial cell line (a line immortalized by transfection with the simian virus 40 large T-antigen), they also demonstrated in vitro that treatment with TGF-β1 induced upregulation of EMT markers, such as vimentin, N-cadherin, and fibronectin, and downregulation of epithelial markers such as cytokeratin. This study suggests that TGF-β1 contributes to esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in EoE, at least in part by inducing EMT.

In addition to its effects on fibrogenesis, TGF-β1 also causes contraction in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells (163). Aceves and colleagues (5) found increased numbers of tryptase-positive mast cells that expressed TGF-β1 in the esophageal smooth muscle of 17 patients with EoE. In this same study, they also demonstrated that TGF-β1 increased the contractility of cultured primary human esophageal smooth muscle cells. Although this study showed that TGF-β1 caused isolated smooth muscle cells to contract, another recent study (130) found that strips of esophageal smooth muscle relaxed in response to treatment with TGF-β1. This observation suggests that TGF-β1 causes neurons in the esophageal enteric plexuses to release inhibitory neurotransmitters that relax smooth muscle. It is not clear whether these TGF-β1 effects on smooth muscle contraction contribute to the clinical manifestations of EoE.

In summary, TGF-β1 exerts effects on fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and smooth muscle cells and probably on enteric neurons that affect muscle contraction. In EoE, TGF-β1 effects on fibroblasts and epithelial cells appear to contribute to fibrogenesis. In other diseases, TGF-β1 also has been found to promote VEGF-dependent angiogenesis (40, 153). Aceves et al. (7) reported increased vascular density and expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 in the lamina propria of esophageal biopsies from patients with EoE (7). Persad et al. (122) also demonstrated increased expression of VCAM-1, and also VEGF, in esophageal biopsies of patients with EoE. Angiogenesis almost certainly plays an important role in EoE tissue remodeling, and further studies are needed to elucidate the precise contribution of TGF-β1 to angiogenesis in EoE.

Th2 Cytokines

Studies have indicated that IL-4 and IL-13, Th2 cytokines that are often overproduced in allergic disorders, have direct profibrotic and remodeling effects in a number of diseases including asthma, atopic dermatitis, schistosomiasis, and chronic colitis (15, 27, 41, 47, 55, 72, 166). IL-4 and IL-13 induce the expression of activated fibroblast markers (α-SMA, fibronectin, CTGF), and, in human fibroblasts and stellate cells, IL-4 and IL-13 regulate the expression of matrix proteins (collagen, MMP, periostin) (9, 92, 105, 125, 151). In addition to these profibrotic effects, IL-13 and IL-4 also can induce fibroblasts to produce proinflammatory substances, including the eosinophil chemoattractant eotaxin (59, 60).

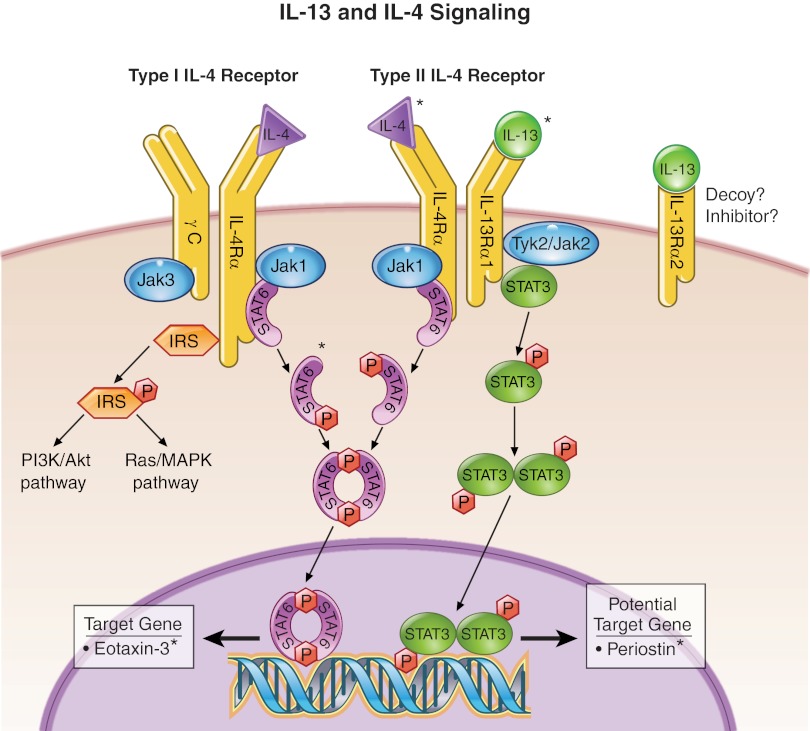

IL-13 and IL-4 share many of the same biological effects, probably because both cytokines bind the Type II IL-4 receptor, which is comprised of IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 subunits (Fig. 3) (67, 75, 79). The cytoplasmic tails of these subunits are associated with tyrosine kinases of the Janus family (Jak 1–2 and Tyk2). When activated by either IL-13 or IL-4 ligands, the receptor subunits heterodimerize and enhance Jak activity. IL-13Rα1 activates Jak2 and/or Tyk2. IL-4Rα activates Jak1. Subsequently, phosphorylation of signaling molecules such as signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3, STAT6, and insulin receptor substrate (IRS) occurs. Once phosphorylated, STAT6 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus to initiate transcription of its target genes such as eotaxin-3, which is highly upregulated in EoE (18). Similarly, STAT3 dimerizes after phosphorylation and translocates to the nucleus to initiate transcription. Periostin, which is discussed further below, may be a potential target gene because its promoter contains putative STAT3 binding sites. IL-4Rα can also heterodimerize with a γ-chain (γC) subunit to form the Type I IL-4 receptor, whereas IL-13Rα1 cannot (75). The γC subunit is associated with Jak3, which becomes activated upon IL-4 receptor binding. Thus variability in the activation of these receptor subunits may account for some of the disparate functions of IL-13 and IL-4 (39, 79, 99).

Fig. 3.

Interleukin (IL)-13 and IL-4 signaling pathway. When the receptor subunits IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 bind to their respective ligands, heterodimerization occurs (IL-4Rα-IL-13Rα1 or IL-4Rα-γC), which enhances Janus kinase (JAK) activity. Subsequently, signaling molecules such as signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)6, STAT3, and insulin receptor substrate (IRS) are phosphorylated and activated. STAT6 and STAT3 are transcription factors that can initiate transcription of target genes including eotaxin-3 and, potentially, periostin. IRS can initiate other pathways such as PI3K/Akt and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which can regulate survival and proliferation. The function of IL-13Rα2 is unclear but may operate as a decoy or inhibitor. *Protein has been linked to EoE.

IRS proteins comprise a family of cytoplasmic proteins that function as signaling intermediates when their tyrosine residues are phosphorylated by activated cell surface receptors. The IRS cascade engages two pathways, PI3K/Akt and Ras/MAPK, whose downstream proteins are many and beyond the scope of this review. In general, the PI3K/Akt pathway regulates cell growth, survival, and protein synthesis, whereas the Ras/MAPK pathway mediates cell proliferation and differentiation. IRS proteins were first identified for their role in insulin signaling, and they are major downstream effectors of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R). IGF-1 can stimulate collagen synthesis and influence myofibroblast activation, proliferation, and survival (46, 137, 164), and IGF-1 signaling appears to play an important role in fibrogenesis in the lungs and intestines (42, 154, 165). Thus there is reason to suspect that IRS signaling might mediate some profibrotic effects of IL-4 and IL-13 in EoE. Interestingly, studies on intestinal and pulmonary fibrosis have suggested that IL-4 and IL-13 also can induce IGF-I expression although the mechanisms underlying this expression appeared to be cell-type dependent. In colonocytes, IL-13 stimulates IGF-I expression via IL-13Rα2 and TGFβ1 signaling (42), whereas IGF-I expression induced by IL-4 and IL-13 in alveolar macrophages seems to be STAT6 dependent (165). Little is known about the role of IGF-1 signaling in EoE fibrogenesis, and, clearly, studies on this issue are warranted.

The relationship between IL-13 and TGF-β is complex, and there appear to be both TGFβ-dependent and TGFβ-independent pathways by which IL-13 exerts its profibrotic effects. IL-13 can induce the production of latent TGF-β (i.e., TGF-β bound to LAP) in macrophages, and IL-13 also can upregulate MMP- and plasmin protease-mediated activation of latent TGF-β, thereby enabling TGF-β to exert its profibrotic effects (81, 83). In IL-13 transgenic mice, the development of subepithelial fibrosis in the lungs is reduced significantly by treatment with TGF-β antagonists (83). Thus the profibrotic effects of IL-13 in this model are TGF-β dependent. However, in a mouse model of IL-13-dependent liver fibrosis caused by Schistosoma mansoni infection, disruption of all or part of the TGF-β cascade still results in liver fibrosis (72). In this model, therefore, the profibrotic effects of IL-13 are TGF-β independent.

Interestingly, IL-13 has another receptor subunit, IL-13Rα2, which binds IL-13 exclusively and with high affinity (Fig. 3). This receptor appears to lack a signaling motif and exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms. Thus, IL-13Rα2 initially was thought to be a “decoy” receptor for IL-13 (i.e., one that binds IL-13 without producing biological effects) (35, 169), and researchers studying models of pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis suggested that IL-13Rα2 might function to abrogate the profibrotic effects of IL-13 (30, 170). In colitis models, however, IL-13Rα2 has been implicated as an inducer of TGF-β-dependent fibrosis (41, 42). Therefore, the function of IL-13Rα2 is still unclear and may be organ specific.

IL-5, another Th2 cytokine, appears to promote fibrosis primarily through its effects on eosinophils (31, 128). IL-5 is known to play key roles in the differentiation, activation, and recruitment of eosinophils, and, as discussed above, eosinophils are important producers of profibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β1 and IL-13. Most studies suggest that IL-5 does not increase fibrosis directly, but rather indirectly by increasing the levels of profibrotic effector molecules (e.g., TGF-β, IL-13) secreted by eosinophils (20, 31, 43, 65, 157).

In animal models, fibrosis and other features of remodeling can be prevented by IL-5 deficiency or by treatment with anti-IL-5 antibodies (20, 31, 43, 65, 157). For example, wild-type mice administered Aspergillus fumigatus intranasally develop eosinophilic esophagitis with deposition of collagen in the esophageal lamina propria and thickening of the esophageal basal cell layer. In IL-5-deficient mice, however, intranasal administration of Aspergillus fumigatus results in significantly less collagen deposition and less basal layer thickening (103). CD2-IL-5 transgenic mice, which overexpress IL-5 in lymphocytes, develop esophageal eosinophilia and remodeling. However, CD2-IL-5 transgenic mice that are also deficient in the eosinophil chemoattractant eotaxin-1 exhibit substantially less esophageal eosinophilia and remodeling (103). Furthermore, an eosinophil-deficient CD2-IL-5 transgenic mouse does not develop esophageal strictures (98). These studies demonstrate that IL-5 overproduction alone is not sufficient to induce esophageal remodeling in the absence of eosinophils.

Unlike IL-5, IL-13 appears to induce esophageal remodeling through effects that are independent of eosinophils. An interesting animal model of EoE involves rtTA-CCL10-IL-13 mice that overexpress IL-13 in the lung and esophagus when induced with doxycycline (171). This IL-13 overexpression causes esophageal remodeling with fibrosis and stricture formation, even in rtTA-CC10-IL-13 mice that are deficient in eosinophils (98, 171). In addition, the IL-13-induced remodeling is significantly enhanced by deletion of IL-13Rα2, suggesting that IL-13Rα2 inhibits remodeling induced by this Th2 cytokine. Thus IL-13 appears to induce fibrosis directly, whereas IL-5 promotes fibrosis indirectly through its effects on eosinophils. These findings challenge the notion that therapies directed only at eosinophils will be sufficient to prevent fibrosis and remodeling in EoE.

Periostin

A role for the ECM protein periostin has been established in a number of conditions characterized by tissue remodeling including asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, myocardial infarction, valvular heart disease, bone development, and certain cancers (56, 80, 100, 106, 114). Periostin is a secreted, 90-kDa, disulfide-linked protein that was formerly known as osteoblast-specific factor 2 (152). Periostin has the ability to bind to itself and to other matrix proteins including tenascin-C, fibronectin, and collagen (56, 80, 151). In particular, periostin facilitates collagen cross-linking by enhancing the proteolytic activation of lysyl oxidase, an enzyme responsible for cross-link formations (97). Periostin also can bind integrins in the cell membrane, an interaction that has the potential to initiate a variety of biological effects including cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and differentiation (25, 37, 51, 114, 118). For example, binding of periostin to the integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, and α6β4 has been shown to trigger crosstalk with epidermal growth factor receptor, which initiates the Akt/protein kinase B (PKB) and focal adhesion kinase-mediated signaling pathways (106). These pathways are involved in cell migration/invasion and EMT.

Some studies in cancer cells have explored a role for periostin as an inducer of EMT that upregulates mesenchymal markers such as vimentin, fibronectin, and MMP-9 and downregulates epithelial markers such as E-cadherin (77, 167). It is conceivable that periostin might also induce EMT in EoE, thereby contributing to tissue remodeling. In some tissues, periostin has been shown to induce profibrotic effects such as increased collagen matrix contraction and increased expression of α-SMA, collagen, and fibronectin (38, 160). In addition, periostin has been implicated in upregulating TGF-β activation in epithelial cells, an effect that might perpetuate a fibrogenic signaling cycle (136). Although TGF-β, IL-13, and IL-4 all appear to have a role in regulating periostin, the transcriptional regulation of this matrix protein is incompletely understood (63, 151).

In the esophagus of patients with EoE, periostin has been shown to be one of the most highly upregulated (46-fold) genes, second in upregulation magnitude only to the eotaxin-3 gene (19). Blanchard et al. (17) have shown that TGF-β1 and IL-13 can induce periostin expression in esophageal fibroblasts and that only IL-13 can induce periostin in epithelial cells. They also have demonstrated that eosinophil recruitment is significantly decreased in allergen-challenged, periostin-null mice and that periostin increases eosinophil adhesion to fibronectin. These observations suggest that periostin plays a role in eosinophil recruitment and trafficking. Thus periostin appears to play an important role in EoE remodeling (Table 2). However, further studies are needed to determine whether periostin influences remodeling primarily by acting as a ligand for integrins in the esophagus, by its effects on eosinophils, or by activating fibrogenic genes in other cells.

Table 2.

Possible biological interactions and effects of periostin in EoE

| Biological Interactions | Effects |

|---|---|

| Periostin-Fibroblasts | Fibroblasts express periostin. |

| Periostin induces profibrotic effects and genes (e.g., matrix contraction, α-smooth muscle actin, collagen, fibronectin). | |

| Periostin-Epithelial Cells | Epithelial cells express periostin. |

| Periostin induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition. | |

| Periostin-Extracellular Matrix Proteins | Periostin binds to collagen, fibronectin, tenascin-C, and itself. |

| Periostin enhances collagen cross-linking. | |

| Periostin-Eosinophils | Periostin increases eosinophil adhesion to fibronectin. |

| Periostin enhances eosinophil recruitment. | |

Periostin likely contributes to eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) remodeling, but further studies are needed to verify these potential interactions and mechanisms.

EoE Therapies and Remodeling

Studies on EoE treatments have been hampered by a paucity of appropriate animal models for the disease. Animal models that have been used to study EoE remodeling include the IL-5 transgenic mouse, the IL-13 transgenic mouse, and the ovalbumin-challenged mouse models. The IL-5 transgenic mouse model involves intranasal administration of a fungal allergen (Aspergillus fumigatus) to anesthetized mice that overexpress IL-5 under the control of a T cell (CD2) promoter (103). In this model, intranasal administration of Aspergillus to anesthetized mice (a technique that delivers the allergen to both the lungs and the esophagus) appears to be required, as oral or intragastric administration alone does not elicit eosinophilia (102). The IL-13 transgenic mouse model involves doxycycline-inducible overexpression of IL-13 under the promoter control of Clara cells (CC10), which are found in the small airways of the lungs (171). These mice develop both pulmonary and esophageal eosinophilia. The IL-5 and IL-13 transgenic models involve genetically engineered overexpression of individual Th2 cytokines, which results in esophageal eosinophilia and remodeling. However, esophageal eosinophilia is not required for tissue remodeling in the IL-13 transgenic mouse. The ovalbumin-challenged mouse model does not involve genetic manipulations. Rather, BALB/c mice are sensitized to ovalbumin by intraperitoneal administration of the egg allergen, followed by the chronic intraesophageal administration of ovalbumin (133). These animals also develop esophageal eosinophilia and remodeling. Although the esophageal changes described in these animal models resemble those seen in patients with EoE, it is not clear how closely these models recapitulate the human disease.

For patients with EoE, treatment options include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), diet therapy, systemic and topical corticosteroids, anti-IL-5 antibodies, and esophageal dilation (89). However, authorities disagree on the issue of what is the appropriate endpoint for assessing the efficacy of these treatments. Some feel that symptom relief alone is an adequate endpoint, whereas others insist that, in addition to relieving symptoms, an effective treatment should cause resolution of esophageal eosinophilia. In most published studies on EoE therapies, the endpoints assessed have been symptoms and esophageal eosinophil levels (52, 69, 76, 78, 90, 96, 134, 138–140). Given the difficulty in procuring deep (lamina propria-containing) mucosal biopsies, relatively few studies have addressed the effects of EoE treatments on esophageal fibrosis and remodeling (2, 6, 33, 68, 93, 144–146).

In regard to the endpoint of remodeling, topical corticosteroids have been the most extensively studied of the EoE therapies. One study found that patients with EoE who responded to treatment with swallowed fluticasone propionate exhibited reduced IL-13 mRNA levels and reversal of the EoE transcriptome (18). Several reports have suggested that TGF-β1 expression is reduced by corticosteroid treatment. In a retrospective study of 16 children with EoE who had been treated with oral budesonide 1 mg daily for at least 3 mo, for example, Aceves and her colleagues (6) assessed fibrosis, TGF-β1 activation, and vascular activation (VCAM-1) in pre- and posttreatment esophageal biopsy specimens. They concluded that, in the 9 patients for whom budesonide reduced eosinophil density to ≤7 eosinophils/hpf, there was an accompanying reduction in esophageal remodeling as evidenced by significantly lower fibrosis scores, significant reductions in the numbers of TGF-β1-positive and pSmad2/3-positive cells, and decreased number of VCAM-1-positive vessels. Straumann and his colleagues (144) randomized 36 adolescent or adult patients with EoE to receive either high-dose (2 mg daily) budesonide or placebo for 15 days. They found significant reductions in esophageal fibrosis scores, TGF-β1 staining, and tenascin-C staining in the group treated with budesonide. In a subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted by the same investigators, patients who received 50 wk of treatment with low-dose (0.25 mg twice daily) budesonide exhibited no reductions in those same parameters (145). However, the overall extent of esophageal remodeling was significantly less in the treated group, and endoscopic ultrasonography of the treated patients showed a significant reduction in their esophageal wall thickness. Finally, Lucendo et al. (93) studied 10 adult patients treated with fluticasone (400 μg twice daily) for 1 yr and found only insignificant reductions in subepithelial fibrosis and in the levels of profibrogenic genes for IL-5, TGF-β1, and FGF9 quantified by real-time PCR. However, they did note a significant decrease in levels of CCL18, which is an eosinophil-derived chemokine that induces collagen production in fibroblasts (12).

IL-5 plays key roles in eosinophil production, differentiation, recruitment, activation, and survival, and the elimination of IL-5 has been shown to improve esophageal eosinophilia in animal models of EoE (103). Several studies in patients with EoE have explored treatment with anti-IL-5 antibodies (11, 139, 140, 146), but these studies have focused primarily on effects on symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia, not on remodeling. Overall, anti-IL-5 antibody therapy appears to decrease esophageal eosinophilia somewhat but has only inconsistent effects on EoE symptoms. Stein et al. (140) noted that three of four adults with EoE exhibited a twofold decrease in epithelial hyperplasia after 3 mo of treatment with mepolizumab (humanized monoclonal IL-5 antibody) in an open-label trial (140). In contrast, a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective study of 59 children who received monthly mepolizumab infusions found no significant improvement in epithelial hyperplasia or lamina propria fibrosis (11). Finally, Straumann and colleagues (146) detected decreases in tenascin-C and TGF-β1 expression in the esophageal epithelium of adult patients with EoE after 13 wk of mepolizumab therapy (146).

Dietary therapies including amino-acid-based elemental diets, allergy-testing-directed diets, and empiric six-food-elimination diets, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing esophageal eosinophil density and symptoms in children and adults with EoE, but few data are available regarding dietary effects on tissue remodeling (52, 76, 96, 138). Recently, one retrospective study explored whether dietary therapy could reverse esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with EoE (91). The investigators performed trichrome stains to evaluate fibrosis on pre- and posttreatment esophageal biopsy specimens and found that diet therapy (elemental and elimination diets) resulted in resolution of fibrosis in 3 of 17 patients (18%). Complete resolution of fibrosis also was observed in five of nine patients (56%) treated with corticosteroids. Another retrospective study assessed treatment effects on esophageal remodeling by quantifying EMT scores in esophageal biopsy specimens from 18 children before and after diet or corticosteroid therapy (68). Elemental diet, six-food-elimination diet, and topical corticosteroids all decreased EMT scores significantly by 81.2%, 72.8%, and 68.2%, respectively.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and EoE can have similar symptoms and histological findings, including dense esophageal eosinophilia, and a trial of PPI therapy has been recommended to distinguish the two disorders (48). The premise underlying this recommendation has been that inhibition of gastric acid secretion is the only important effect of PPIs, and therefore only an acid-peptic disorder like GERD can respond to PPI treatment. This assumption has been challenged by a recent study (29) showing that PPIs inhibit Th2 cytokine-stimulated secretion of eotaxin-3 by esophageal squamous epithelial cells. Thus PPIs might have beneficial effects in EoE that are independent of their effects on gastric acid secretion, and PPI-induced inhibition of eotaxin-3 secretion might be expected to alter tissue remodeling. A number of reports have described resolution of esophageal eosinophilia and/or EoE symptoms with PPI therapy, but few studies have explored PPI effects on remodeling (34, 104, 123). One retrospective study examined this issue and found no effects of PPI therapy on subepithelial fibrosis in EoE, even though the PPIs caused symptomatic improvement (87). Further studies to address this issue are warranted.

Reports of small studies have described limited efficacy for anti-TNFα antibodies, anti-IgE antibodies, and leukotriene antagonists in symptom relief for patients with EoE, but these reports also have not described effects on tissue remodeling (13, 54, 94, 131, 143). New therapeutic agents for EoE undoubtedly will emerge as our understanding of the disorder improves. For example, sialic acid binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) are transmembrane protein receptors that contain an NH2-terminal V-like immunoglobulin domain that binds sialic acid. Siglecs are expressed by a number of immune cells, including eosinophils, and Siglecs are involved in regulating inflammation. Rubenstein et al. (133) demonstrated that anti-Siglec-F antibody decreased eosinophil infiltration, angiogenesis, fibronectin deposition, and basal zone hyperplasia in a mouse model of EoE. These findings suggest that Siglec-8, the human paralog of Siglec-F, might be a therapeutic target for improving tissue remodeling in patients with EoE. Anti-IL-4Rα antibodies (AMG 317), anti-IL-4 antibodies (pascolizumab, Nuvance), anti-IL-13 antibodies (tralokinumab), and anti-TGF-β1 antibodies (GC1008) are currently under investigation in clinical trials for airway remodeling in asthma and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and these agents might be expected to have beneficial effects in EoE as well.

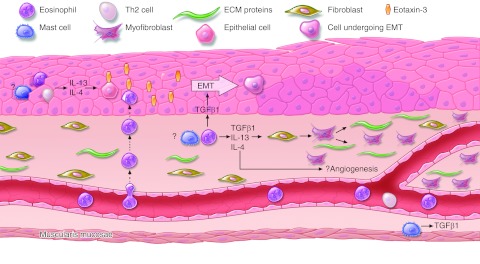

This review has identified a number of molecular mechanisms that contribute to esophageal remodeling in EoE (summarized in Fig. 4). Proteins in these pathways are potential targets for novel treatments that might be used to prevent the troublesome complications of the disease. Well-designed studies that focus specifically on therapeutic effects on remodeling in EoE are sorely needed. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying this remodeling are incompletely understood. Studies designed to elucidate these mechanisms might reveal useful therapeutic targets and might even suggest a means to prevent the development of EoE altogether.

Fig. 4.

Pathogenesis of tissue remodeling in EoE. In the epithelium, eosinophils, Th2 cells and, possibly, mast cells can secrete IL-13 and IL-4. Epithelial cells respond by expressing eotaxin-3, which recruits more eosinophils. Eosinophils (and possibly mast cells) also secrete TGF-β1, which stimulates epithelial cells to undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and acquire fibroblast-like characteristics. TGF-β1, IL-13, and IL-4 also can induce fibroblast activation with myofibroblast transdifferentiation and production of ECM proteins (collagen, fibronectin, tenascin-C, and periostin), resulting in subepithelial fibrosis. TGF-β1, IL-13, and IL-4 all have potential angiogenic properties. Lastly, mast cells in the muscularis mucosae can secrete TGF-β1. The exact nature of TGF-β1 effects on smooth muscle is still unclear.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Office of Medical Research, Department of Veterans Affairs (R. Souza, S. Spechler) and the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK63621 to R. Souza, R01-CA134571 to R. Souza and S. Spechler, K12 HD-068369-01 to E. Cheng), and the American Gastroenterological Association Institute (Fellow to Faculty Transition Award to E. Cheng).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: E.C., R.F.S., and S.J.S. prepared figures; E.C., R.F.S., and S.J.S. drafted manuscript; E.C., R.F.S., and S.J.S. edited and revised manuscript; E.C., R.F.S., and S.J.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, Rainey HF, Collins MH, Stringer K, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126: 140–149, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abu-Sultaneh SM, Durst P, Maynard V, Elitsur Y. Fluticasone and food allergen elimination reverse sub-epithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 56: 97–102, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aceves SS. Tissue remodeling in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: what lies beneath the surface? J Allergy Clin Immunol 128: 1047–1049, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aceves SS, Ackerman SJ. Relationships between eosinophilic inflammation, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 29: 197–211; xiii–xiv, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aceves SS, Chen D, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Mast cells infiltrate the esophageal smooth muscle in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, express TGF-beta1, and increase esophageal smooth muscle contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126: 1198–1204; e1194, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, Mueller J, Dohil R, Hoffman H, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy 65: 109–116, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 119: 206–212, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci 116: 217–224, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aoudjehane L, Pissaia A, Jr, Scatton O, Podevin P, Massault PP, Chouzenoux S, Soubrane O, Calmus Y, Conti F. Interleukin-4 induces the activation and collagen production of cultured human intrahepatic fibroblasts via the STAT-6 pathway. Lab Invest 88: 973–985, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Artuc M, Steckelings UM, Henz BM. Mast cell-fibroblast interactions: human mast cells as source and inducers of fibroblast and epithelial growth factors. J Invest Dermatol 118: 391–395, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Assa'ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, Thomson M, Heath AT, Smith DA, Perschy TL, Jurgensen CH, Ortega HG, Aceves SS. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 141: 1593–1604, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atamas SP, Luzina IG, Choi J, Tsymbalyuk N, Carbonetti NH, Singh IS, Trojanowska M, Jimenez SA, White B. Pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine stimulates collagen production in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29: 743–749, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Attwood SE, Lewis CJ, Bronder CS, Morris CD, Armstrong GR, Whittam J. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: a novel treatment using Montelukast. Gut 52: 181–185, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, Demeester TR, Jones JB. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. A distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 38: 109–116, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Azouz A, Razzaque MS, El-Hallak M, Taguchi T. Immunoinflammatory responses and fibrogenesis. Med Electron Microsc 37: 141–148, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 16: 585–601, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blanchard C, Mingler MK, McBride M, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Chang G, Stringer K, Abonia JP, Molkentin JD, Rothenberg ME. Periostin facilitates eosinophil tissue infiltration in allergic lung and esophageal responses. Mucosal Immunol 1: 289–296, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, Abonia JP, Wu YY, Lu TX, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Wells SI, Rothenberg ME. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120: 1292–1300, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, Jameson SC, Kirby C, Konikoff MR, Collins MH, Cohen MB, Akers R, Hogan SP, Assa'ad AH, Putnam PE, Aronow BJ, Rothenberg ME. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest 116: 536–547, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blyth DI, Wharton TF, Pedrick MS, Savage TJ, Sanjar S. Airway subepithelial fibrosis in a murine model of atopic asthma: suppression by dexamethasone or anti-interleukin-5 antibody. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 23: 241–246, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Booth BW, Adler KB, Bonner JC, Tournier F, Martin LD. Interleukin-13 induces proliferation of human airway epithelial cells in vitro via a mechanism mediated by transforming growth factor-alpha. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 25: 739–743, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bosse Y, Rola-Pleszczynski M. FGF2 in asthmatic airway-smooth-muscle-cell hyperplasia. Trends Mol Med 14: 3–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boxall C, Holgate ST, Davies DE. The contribution of transforming growth factor-beta and epidermal growth factor signalling to airway remodelling in chronic asthma. Eur Respir J 27: 208–229, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brightling C, Berry M, Amrani Y. Targeting TNF-alpha: a novel therapeutic approach for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 121: 5–10; quiz 11–12, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Butcher JT, Norris RA, Hoffman S, Mjaatvedt CH, Markwald RR. Periostin promotes atrioventricular mesenchyme matrix invasion and remodeling mediated by integrin signaling through Rho/PI 3-kinase. Dev Biol 302: 256–266, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cairns JA. Mast cell tryptase and its role in tissue remodelling. Clin Exp Allergy 28: 1460–1463, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheever AW, Williams ME, Wynn TA, Finkelman FD, Seder RA, Cox TM, Hieny S, Caspar P, Sher A. Anti-IL-4 treatment of Schistosoma mansoni-infected mice inhibits development of T cells and non-B, non-T cells expressing Th2 cytokines while decreasing egg-induced hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol 153: 753–759, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chehade M, Sampson HA, Morotti RA, Magid MS. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 45: 319–328, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheng E, Zhang X, Huo X, Yu C, Zhang Q, Wang DH, Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Omeprazole blocks eotaxin-3 expression by oesophageal squamous cells from patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis and GORD. Gut. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiaramonte MG, Mentink-Kane M, Jacobson BA, Cheever AW, Whitters MJ, Goad ME, Wong A, Collins M, Donaldson DD, Grusby MJ, Wynn TA. Regulation and function of the interleukin 13 receptor alpha 2 during a T helper cell type 2-dominant immune response. J Exp Med 197: 687–701, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cho JY, Miller M, Baek KJ, Han JW, Nayar J, Lee SY, McElwain K, McElwain S, Friedman S, Broide DH. Inhibition of airway remodeling in IL-5-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 113: 551–560, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 425: 577–584, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, Bastian J, Aceves S. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 139: 418–429, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dohil R, Newbury RO, Aceves S. Transient PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia may be a clinical sub-phenotype of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 57: 1413–1419, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Donaldson DD, Whitters MJ, Fitz LJ, Neben TY, Finnerty H, Henderson SL, O'Hara RM, Jr, Beier DR, Turner KJ, Wood CR, Collins M. The murine IL-13 receptor alpha 2: molecular cloning, characterization, and comparison with murine IL-13 receptor alpha 1. J Immunol 161: 2317–2324, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elliott CG, Hamilton DW. Deconstructing fibrosis research: do pro-fibrotic signals point the way for chronic dermal wound regeneration? J Cell Commun Signal 5: 301–315, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elliott CG, Wang J, Guo X, Xu SW, Eastwood M, Guan J, Leask A, Conway SJ, Hamilton DW. Periostin modulates myofibroblast differentiation during full-thickness cutaneous wound repair. J Cell Sci 125: 121–132, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Erkan M, Kleeff J, Gorbachevski A, Reiser C, Mitkus T, Esposito I, Giese T, Buchler MW, Giese NA, Friess H. Periostin creates a tumor-supportive microenvironment in the pancreas by sustaining fibrogenic stellate cell activity. Gastroenterology 132: 1447–1464, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fallon PG, Richardson EJ, McKenzie GJ, McKenzie AN. Schistosome infection of transgenic mice defines distinct and contrasting pathogenic roles for IL-4 and IL-13: IL-13 is a profibrotic agent. J Immunol 164: 2585–2591, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ferrari G, Cook BD, Terushkin V, Pintucci G, Mignatti P. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta1) induces angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Physiol 219: 449–458, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fichtner-Feigl S, Strober W, Kawakami K, Puri RK, Kitani A. IL-13 signaling through the IL-13alpha2 receptor is involved in induction of TGF-beta1 production and fibrosis. Nat Med 12: 99–106, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fichtner-Feigl S, Young CA, Kitani A, Geissler EK, Schlitt HJ, Strober W. IL-13 signaling via IL-13R alpha2 induces major downstream fibrogenic factors mediating fibrosis in chronic TNBS colitis. Gastroenterology 135: 2003–2013; e2001–2007, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Flood-Page P, Menzies-Gow A, Phipps S, Ying S, Wangoo A, Ludwig MS, Barnes N, Robinson D, Kay AB. Anti-IL-5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmatics. J Clin Invest 112: 1029–1036, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Forbes SJ, Russo FP, Rey V, Burra P, Rugge M, Wright NA, Alison MR. A significant proportion of myofibroblasts are of bone marrow origin in human liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 126: 955–963, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fox VL, Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. High-resolution EUS in children with eosinophilic “allergic” esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 57: 30–36, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fruchtman S, Simmons JG, Michaylira CZ, Miller ME, Greenhalgh CJ, Ney DM, Lund PK. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-2 modulates the fibrogenic actions of GH and IGF-I in intestinal mesenchymal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G342–G350, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fulkerson PC, Fischetti CA, Hassman LM, Nikolaidis NM, Rothenberg ME. Persistent effects induced by IL-13 in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 35: 337–346, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 133: 1342–1363, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gailit J, Marchese MJ, Kew RR, Gruber BL. The differentiation and function of myofibroblasts is regulated by mast cell mediators. J Invest Dermatol 117: 1113–1119, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gallucci RM, Lee EG, Tomasek JJ. IL-6 modulates alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in dermal fibroblasts from IL-6-deficient mice. J Invest Dermatol 126: 561–568, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gillan L, Matei D, Fishman DA, Gerbin CS, Karlan BY, Chang DD. Periostin secreted by epithelial ovarian carcinoma is a ligand for alpha(V)beta(3) and alpha(V)beta(5) integrins and promotes cell motility. Cancer Res 62: 5358–5364, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology 142: 1451–1459, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gupta N, Mathur SC, Dumot JA, Singh V, Gaddam S, Wani SB, Bansal A, Rastogi A, Goldblum JR, Sharma P. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for postablation surveillance in Barrett's esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc 75: 11–18, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gupta SK, Peters-Golden M, Fitzgerald JF, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Molleston JP, Corkins MR, Lim JR. Cysteinyl leukotriene levels in esophageal mucosal biopsies of children with eosinophilic inflammation: are they all the same? Am J Gastroenterol 101: 1125–1128, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hamid Q, Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Differential in situ cytokine gene expression in acute versus chronic atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 94: 870–876, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hamilton DW. Functional role of periostin in development and wound repair: implications for connective tissue disease. J Cell Commun Signal 2: 9–17, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hardie WD, Korfhagen TR, Sartor MA, Prestridge A, Medvedovic M, Le Cras TD, Ikegami M, Wesselkamper SC, Davidson C, Dietsch M, Nichols W, Whitsett JA, Leikauf GD. Genomic profile of matrix and vasculature remodeling in TGF-alpha induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 309–321, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hirota N, Risse PA, Novali M, McGovern T, Al-Alwan L, McCuaig S, Proud D, Hayden P, Hamid Q, Martin JG. Histamine may induce airway remodeling through release of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands from bronchial epithelial cells. FASEB J 26: 1704–1716, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hoeck J, Woisetschlager M. Activation of eotaxin-3/CCLl26 gene expression in human dermal fibroblasts is mediated by STAT6. J Immunol 167: 3216–3222, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hoeck J, Woisetschlager M. STAT6 mediates eotaxin-1 expression in IL-4 or TNF-alpha-induced fibroblasts. J Immunol 166: 4507–4515, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hogan SP. Functional role of eosinophils in gastrointestinal inflammation. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 29: 129–140; xi, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hogan SP, Rosenberg HF, Moqbel R, Phipps S, Foster PS, Lacy P, Kay AB, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophils: biological properties and role in health and disease. Clin Exp Allergy 38: 709–750, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Horiuchi K, Amizuka N, Takeshita S, Takamatsu H, Katsuura M, Ozawa H, Toyama Y, Bonewald LF, Kudo A. Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor beta. J Bone Miner Res 14: 1239–1249, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hsu Blatman KS, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Bryce PJ. Expression of mast cell-associated genes is upregulated in adult eosinophilic esophagitis and responds to steroid or dietary therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127: 1307–1308; e1303, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huaux F, Liu T, McGarry B, Ullenbruch M, Xing Z, Phan SH. Eosinophils and T lymphocytes possess distinct roles in bleomycin-induced lung injury and fibrosis. J Immunol 171: 5470–5481, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jacoby DB, Gleich GJ, Fryer AD. Human eosinophil major basic protein is an endogenous allosteric antagonist at the inhibitory muscarinic M2 receptor. J Clin Invest 91: 1314–1318, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jiang H, Harris MB, Rothman P. IL-4/IL-13 signaling beyond JAK/STAT. J Allergy Clin Immunol 105: 1063–1070, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kagalwalla AF, Akhtar N, Woodruff SA, Rea BA, Masterson JC, Mukkada V, Parashette KR, Du J, Fillon S, Protheroe CA, Lee JJ, Amsden K, Melin-Aldana H, Capocelli KE, Furuta GT, Ackerman SJ. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Epithelial mesenchymal transition contributes to esophageal remodeling and reverses with treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129: 1387–1396, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Hess T, Nelson SP, Emerick KM, Melin-Aldana H, Li BU. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4: 1097–1102, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112: 1776–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kanbe N, Tanaka A, Kanbe M, Itakura A, Kurosawa M, Matsuda H. Human mast cells produce matrix metalloproteinase 9. Eur J Immunol 29: 2645–2649, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kaviratne M, Hesse M, Leusink M, Cheever AW, Davies SJ, McKerrow JH, Wakefield LM, Letterio JJ, Wynn TA. IL-13 activates a mechanism of tissue fibrosis that is completely TGF-beta independent. J Immunol 173: 4020–4029, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kay AB. The role of eosinophils in the pathogenesis of asthma. Trends Mol Med 11: 148–152, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kay AB, Phipps S, Robinson DS. A role for eosinophils in airway remodelling in asthma. Trends Immunol 25: 477–482, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kelly-Welch AE, Hanson EM, Boothby MR, Keegan AD. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling connections maps. Science 300: 1527–1528, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology 109: 1503–1512, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kim CJ, Sakamoto K, Tambe Y, Inoue H. Opposite regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cell invasiveness by periostin between prostate and bladder cancer cells. Int J Oncol 38: 1759–1766, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, Akers R, Cohen MB, Collins MH, Assa'ad AH, Aceves SS, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 131: 1381–1391, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kruse S, Braun S, Deichmann KA. Distinct signal transduction processes by IL-4 and IL-13 and influences from the Q551R variant of the human IL-4 receptor alpha chain. Respir Res 3: 24, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kudo A. Periostin in fibrillogenesis for tissue regeneration: periostin actions inside and outside the cell. Cell Mol Life Sci 68: 3201–3207, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lanone S, Zheng T, Zhu Z, Liu W, Lee CG, Ma B, Chen Q, Homer RJ, Wang J, Rabach LA, Rabach ME, Shipley JM, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Elias JA. Overlapping and enzyme-specific contributions of matrix metalloproteinases-9 and -12 in IL-13-induced inflammation and remodeling. J Clin Invest 110: 463–474, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lazaar AL, Plotnick MI, Kucich U, Crichton I, Lotfi S, Das SK, Kane S, Rosenbloom J, Panettieri RA, Jr, Schechter NM, Pure E. Mast cell chymase modifies cell-matrix interactions and inhibits mitogen-induced proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol 169: 1014–1020, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Lanone S, Wang X, Koteliansky V, Shipley JM, Gotwals P, Noble P, Chen Q, Senior RM, Elias JA. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor beta(1). J Exp Med 194: 809–821, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Levi-Schaffer F, Austen KF, Caulfield JP, Hein A, Bloes WF, Stevens RL. Fibroblasts maintain the phenotype and viability of the rat heparin-containing mast cell in vitro. J Immunol 135: 3454–3462, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Levi-Schaffer F, Austen KF, Caulfield JP, Hein A, Gravallese PM, Stevens RL. Co-culture of human lung-derived mast cells with mouse 3T3 fibroblasts: morphology and IgE-mediated release of histamine, prostaglandin D2, and leukotrienes. J Immunol 139: 494–500, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Levi-Schaffer F, Weg VB. Mast cells, eosinophils and fibrosis. Clin Exp Allergy 27, Suppl 1: 64–70, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Levine J, Lai J, Edelman M, Schuval SJ. Conservative long-term treatment of children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 108: 363–366, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. LeviSchaffer F, Temkin V, Zilberman Y. Mast cell sonicates enhance eosinophil survival: A GM-CSF mediated effect. J Allergy Clin Immunol 97: 354–354, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 89. Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, Dohil R, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, Katzka DA, Lucendo AJ, Markowitz JE, Noel RJ, Odze RD, Putnam PE, Richter JE, Romero Y, Ruchelli E, Sampson HA, Schoepfer A, Shaheen NJ, Sicherer SH, Spechler S, Spergel JM, Straumann A, Wershil BK, Rothenberg ME, Aceves SS. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128: 3–20; quiz 21–22, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Liacouras CA, Wenner WJ, Brown K, Ruchelli E. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis in children: successful treatment with oral corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 26: 380–385, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lieberman JA, Morotti RA, Konstantinou GN, Yershov O, Chehade M. Dietary therapy can reverse esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a historical cohort. Allergy 67: 1299–1307, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Liu Y, Meyer C, Muller A, Herweck F, Li Q, Mullenbach R, Mertens PR, Dooley S, Weng HL. IL-13 induces connective tissue growth factor in rat hepatic stellate cells via TGF-beta-independent Smad signaling. J Immunol 187: 2814–2823, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lucendo AJ, Arias A, De Rezende LC, Yague-Compadre JL, Mota-Huertas T, Gonzalez-Castillo S, Cuesta RA, Tenias JM, Bellon T. Subepithelial collagen deposition, profibrogenic cytokine gene expression, and changes after prolonged fluticasone propionate treatment in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128: 1037–1046, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lucendo AJ, De Rezende LC, Jimenez-Contreras S, Yague-Compadre JL, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Mota-Huertas T, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, Gonzalez-Castillo S, Arias A. Montelukast was inefficient in maintaining steroid-induced remission in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 56: 3551–3558, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Luo JC, Shin VY, Yang YH, Wu WK, Ye YN, So WH, Chang FY, Cho CH. Tumor necrosis factor-α stimulates gastric epithelial cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288: G32–G38, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol 98: 777–782, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Maruhashi T, Kii I, Saito M, Kudo A. Interaction between periostin and BMP-1 promotes proteolytic activation of lysyl oxidase. J Biol Chem 285: 13294–13303, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mavi P, Rajavelu P, Rayapudi M, Paul RJ, Mishra A. Esophageal functional impairments in experimental eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G1347–G1355, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. McKenzie GJ, Bancroft A, Grencis RK, McKenzie AN. A distinct role for interleukin-13 in Th2-cell-mediated immune responses. Curr Biol 8: 339–342, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Merle B, Garnero P. The multiple facets of periostin in bone metabolism. Osteoporos Int 23: 1199–1212, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Micera A, Vigneti E, Pickholtz D, Reich R, Pappo O, Bonini S, Maquart FX, Aloe L, Levi-Schaffer F. Nerve growth factor displays stimulatory effects on human skin and lung fibroblasts, demonstrating a direct role for this factor in tissue repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6162–6167, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. J Clin Invest 107: 83–90, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Mishra A, Wang M, Pemmaraju VR, Collins MH, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Esophageal remodeling develops as a consequence of tissue specific IL-5-induced eosinophilia. Gastroenterology 134: 204–214, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Ripoll C, Hernandez-Alonso M, Mateos JM, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Duenas C, Fernandez-Gonzalez N, Quintana EM, Gonzalez-Nunez MA. Esophageal eosinophilic infiltration responds to proton pump inhibition in most adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 110–117, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Moriya C, Jinnin M, Yamane K, Maruo K, Muchemwa FC, Igata T, Makino T, Fukushima S, Ihn H. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-13 is controlled by IL-13 via PI3K/Akt3 and PKC-delta in normal human dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 131: 655–661, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Morra L, Moch H. Periostin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a review and an update. Virchows Arch 459: 465–475, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Mueller S, Aigner T, Neureiter D, Stolte M. Eosinophil infiltration and degranulation in oesophageal mucosa from adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis: a retrospective and comparative study on pathological biopsy. J Clin Pathol 59: 1175–1180, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mulder DJ, Pacheco I, Hurlbut DJ, Mak N, Furuta GT, MacLeod RJ, Justinich CJ. FGF9-induced proliferative response to eosinophilic inflammation in oesophagitis. Gut 58: 166–173, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Munger JS, Sheppard D. Cross talk among TGF-beta signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a005017, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Munitz A, Levi-Schaffer F. Eosinophils: ‘new’ roles for ‘old’ cells. Allergy 59: 268–275, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Nicholson AG, Li D, Pastorino U, Goldstraw P, Jeffery PK. Full thickness eosinophilia in oesophageal leiomyomatosis and idiopathic eosinophilic oesophagitis. A common allergic inflammatory profile? J Pathol 183: 233–236, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Nico B, Mangieri D, Benagiano V, Crivellato E, Ribatti D. Nerve growth factor as an angiogenic factor. Microvasc Res 75: 135–141, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Norrby K. Mast cells and angiogenesis. APMIS 110: 355–371, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Norris RA, Borg TK, Butcher JT, Baudino TA, Banerjee I, Markwald RR. Neonatal and adult cardiovascular pathophysiological remodeling and repair: developmental role of periostin. Ann NY Acad Sci 1123: 30–40, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Okada S, Kita H, George TJ, Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM. Migration of eosinophils through basement membrane components in vitro: role of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 17: 519–528, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Okayama Y, el-Lati SG, Leiferman KM, Church MK. Eosinophil granule proteins inhibit substance P-induced histamine release from human skin mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 93: 900–909, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Okayama Y, Ra C, Saito H. Role of mast cells in airway remodeling. Curr Opin Immunol 19: 687–693, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Ontsuka K, Kotobuki Y, Shiraishi H, Serada S, Ohta S, Tanemura A, Yang L, Fujimoto M, Arima K, Suzuki S, Murota H, Toda S, Kudo A, Conway SJ, Narisawa Y, Katayama I, Izuhara K, Naka T. Periostin, a matricellular protein, accelerates cutaneous wound repair by activating dermal fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol 21: 331–336, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ortiz LA, Lasky J, Gozal E, Ruiz V, Lungarella G, Cavarra E, Brody AR, Friedman M, Pardo A, Selman M. Tumor necrosis factor receptor deficiency alters matrix metalloproteinase 13/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 expression in murine silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 244–252, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Parfitt JR, Gregor JC, Suskin NG, Jawa HA, Driman DK. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: distinguishing features from gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study of 41 patients. Mod Pathol 19: 90–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Patella V, de Crescenzo G, Marino I, Genovese A, Adt M, Gleich GJ, Marone G. Eosinophil granule proteins are selective activators of human heart mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 113: 200–202, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Persad R, Huynh HQ, Hao L, Ha JR, Sergi C, Srivastava R, Persad S. Angiogenic remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with increased levels of VEGFA, angiogenin, IL-8 and activation of the TNF-alpha-NFkappaB pathway. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 55: 251–260, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Peterson KA, Thomas KL, Hilden K, Emerson LL, Wills JC, Fang JC. Comparison of esomeprazole to aerosolized, swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 55: 1313–1319, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Piera-Velazquez S, Li Z, Jimenez SA. Role of endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders. Am J Pathol 179: 1074–1080, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Postlethwaite AE, Holness MA, Katai H, Raghow R. Human fibroblasts synthesize elevated levels of extracellular matrix proteins in response to interleukin 4. J Clin Invest 90: 1479–1485, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Potter JW, Saeian K, Staff D, Massey BT, Komorowski RA, Shaker R, Hogan WJ. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: an emerging problem with unique esophageal features. Gastrointest Endosc 59: 355–361, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Powell PP, Klagsbrun M, Abraham JA, Jones RC. Eosinophils expressing heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor mRNA localize around lung microvessels in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Pathol 143: 784–793, 1993 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Reiman RM, Thompson RW, Feng CG, Hari D, Knight R, Cheever AW, Rosenberg HF, Wynn TA. Interleukin-5 (IL-5) augments the progression of liver fibrosis by regulating IL-13 activity. Infect Immun 74: 1471–1479, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Ribatti D, Ranieri G, Nico B, Benagiano V, Crivellato E. Tryptase and chymase are angiogenic in vivo in the chorioallantoic membrane assay. Int J Dev Biol 55: 99–102, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Rieder F, Nonevski I, Ma J, Ouyang Z, West G, Protheroe CA, Schirbel A, Goldblum JR, Bonfield TL, Harnett KM, Lee JJ, Hirano I, Falk GW, Biancani P, Fiocchi C. Eosinophil derived TGF-β1 activates human esophageal mesenchymal cells and alters esophageal motility - implications for dysphagia in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Gastroenterology 142: S116, 2012 [Google Scholar]