Abstract

Progranulin (PGRN), a secreted growth factor, regulates the proliferation of various epithelial cells. Its mechanism of action is largely unknown. Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) is a protein deacetylase that is known to regulate the transcriptional activity of the forkhead receptor FOXO1, thereby modulating the balance between proapoptotic and cell cycle-arresting genes. We have shown that PGRN is overexpressed in cholangiocarcinoma and stimulates proliferation. However, its effects on hyperplastic cholangiocyte proliferation are unknown. In the present study, the expression of PGRN and its downstream targets was determined after bile duct ligation (BDL) in mice and in a mouse cholangiocyte cell line after stimulation with PGRN. The effects of PGRN on cholangiocyte proliferation were assessed in sham-operated (sham) and BDL mice treated with PGRN or by specifically knocking down endogenous PGRN expression using Vivo-Morpholinos or short hairpin RNA. PGRN expression and secretion were upregulated in proliferating cholangiocytes isolated after BDL. Treatment of mice with PGRN increased biliary mass and cholangiocyte proliferation in vivo and in vitro and enhanced cholangiocyte proliferation observed after BDL. PGRN treatment decreased Sirt1 expression and increased the acetylation of FOXO1, resulting in the cytoplasmic accumulation of FOXO1 in cholangiocytes. Overexpression of Sirt1 in vitro prevented the proliferative effects of PGRN. Conversely, knocking down PGRN expression in vitro or in vivo inhibited cholangiocyte proliferation. In conclusion, these data suggest that the upregulation of PGRN may be a key feature stimulating cholangiocyte proliferation. Modulating PGRN levels may be a viable technique for regulating the balance between ductal proliferation and ductopenia observed in a variety of cholangiopathies.

Keywords: biliary epithelium, forkhead, bile duct ligation, sirtuin 1, acetylation

cholangiocytes are epithelial cells that line the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts and are the target cells in cholangiopathies such as primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (3). During the course of these diseases, as well as in many forms of liver injury (e.g., in response to alcohol, toxins, or drugs) (3, 39), a balance exists between cholangiocyte proliferation and loss, which is critical for the homeostasis of biliary mass. Recently, considerable effort has gone into identifying the factors that control biliary loss/proliferation in an attempt to identify potential therapeutic targets for the maintenance of biliary mass during cholestatic liver diseases.

Functional and proliferative heterogeneity of the biliary tree exists (21, 35). The subpopulation of cholangiocytes that proliferate to increase biliary mass varies depending on the stimulus. For example, under conditions of biliary obstruction, the increase in biliary mass is predominantly due to the proliferation of the large cholangiocytes lining the large bile ducts (2), whereas under conditions of liver injury, where large cholangiocytes are damaged, the small, less-differentiated cholangiocytes of the cholangioles are thought to proliferate and differentiate to compensate for the loss of the damaged large cholangiocytes (32, 33). Furthermore, agents that cause an increase in biliary mass under physiological conditions can target either small or large cholangiocytes. For example, agents that stimulate the histamine H1 receptor or the α1-adrenergic receptor stimulate the proliferation of small but not large cholangiocytes (1, 17), whereas feeding with the bile acids taurocholate and taurolithocholate increased proliferation in large cholangiocytes (5).

Progranulin (PGRN) is a secreted glycoprotein that mediates cell cycle progression and cell motility (26). Little is known about the function of PGRN in the liver. We (16) have recently shown that PGRN expression is upregulated in cholangiocarcinoma, where it has subsequent growth-promoting effects. However, the expression and effects of PGRN in hyperplastic cholangiocyte proliferation are unknown.

We (16) have demonstrated that one of the downstream consequences of PGRN signaling is the nuclear extrusion and hence inhibition of FOXO1 activity in cholangiocarcinoma. FOXO1 is a member of the forkhead family of transcription factors, which are involved in multiple biological processes, such as cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, apoptosis, and autophagy (44). The transcriptional activity of FOXO1 is coordinately regulated by a series of posttranslational modifications including phosphorylation and acetylation events (44). The phosphorylation of FOXO1 is predominantly via Akt-mediated events, although other kinases can phosphorylate FOXO1 (44). Generally, these phosphorylation events result in the nuclear extrusion and cytoplasmic retention of FOXO1, thereby inhibiting its transcriptional activity (44). In addition, deacetylases and acetylases can modify FOXO1, altering its transcriptional activity and interaction with other proteins (44). In particular, sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) is capable of deacetylating FOXO1, thereby increasing its nuclear retention and hence activity (36, 38). Conversely, inhibition of Sirt1 has been shown to increase the acetylation of FOXO1 and decrease its activity (15).

The aims of the present study were to 1) evaluate the expression and secretion of PGRN in cholangiocytes undergoing hyperplastic proliferation and 2) determine the effects of PGRN on cholangiocyte proliferation and assess the intracellular signaling mechanism by which this occurs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant mouse PGRN (rPGRN) and the PGRN-specific EIA kit were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). All primers and short hairpin (sh)RNA plasmids were obtained from SABiosciences (a Qiagen company, Frederick, MD). Vivo-Morpholinos were designed and purchased from Gene-Tools (Philomath, OR). The Sirt1 expression vector (pCMV-Sirt1) and empty vector (pCMV) were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). The PGRN-specific antibody was obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Antibodies to cytokeratin (CK)-7, PCNA, and acetylated FOXO1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The antibodies against total FOXO1 and Sirt1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Cells from the mouse cholangiocyte cell line (MCCLs) were cultured as previously described (34).

Animal Treatment

Male C57/Bl6 mice (20–25 g) were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Animals were kept in a temperature-controlled environment (22°C) with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and with free access to standard rodent chow and water. Experiments were performed in bile duct ligated (BDL) or sham-operated (sham) mice that had been treated with 5 nmol·kg−1·h−1 rPGRN (via implanted Alzet osmotic minipumps) for 3 or 7 days. In parallel, mice were injected with 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 (via tail vein) PGRN-specific Vivo-Morpholino or a mismatched control sequence 24 h before BDL or sham surgery. Daily tail vein injections of Vivo-Morpholino sequences were continued for 2 days postsurgery. Study protocols were performed with strict adherence to institution guidelines and were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cholangiocyte Isolation

Freshly isolated cholangiocytes (97–100% pure by CK-7 immunohistochemistry) from the selected groups of animals were obtained by immunoaffinity separation (4, 6) using a mouse monoclonal antibody (IgM, kindly provided by Dr. R. Faris, Brown University, Providence, RI) against an unidentified membrane antigen expressed by all intrahepatic cholangiocytes. Cell number and viability (>97%) were assessed by standard trypan blue exclusion. For secretion experiments, isolated cholangiocytes were resuspended in HEPES-buffered saline at a density of 10 million cells/ml and incubated for 6 h at 37°C in a shaking water bath. Cells were then centrifuged, and the supernatant was retained and stored at −80°C for experimentation.

PGRN Expression and Secretion

PGRN expression was assessed in isolated cholangiocytes from sham and BDL mice by 1) real-time PCR, 2) immunoblot analysis, and 3) immunohistochemistry in total livers using previously described methodology (12, 14). In addition, PGRN secretion was assessed by EIA on supernatants from a suspension of freshly isolated cholangiocytes from sham and BDL mice following the instructions provided by the vendor.

Analysis of Cholangiocyte Proliferation

Cholangiocyte proliferation was assessed in liver sections from the above-mentioned treatment groups by 1) immunohistochemical staining for CK-7 to assess intrahepatic biliary mass and 2) PCNA immunoreactivity as a marker of proliferative capacity using previously described methods (18, 31). After being stained, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and examined with a microscope (Olympus BX 40, Olympus Optical). Over 100 cholangiocytes were counted in a random, blinded fashion in 3 different fields for each group of animals. Data were expressed as the percentages of CK-7- and PCNA- positive cholangiocytes per portal tract.

The effect of rPGRN treatment on cholangiocyte proliferation was assessed in vitro in MCCLs by MTS cell proliferation assays and PCNA protein expression (12). Briefly, cholangiocytes were treated with rPGRN (at concentrations up to 1 μg/ml) for 48 h. Cell proliferation was assessed using a colorimetric cell proliferation assay (CellTiter 96Aqueous, Promega, Madison, WI). In parallel, cholangiocytes were treated with rPGRN (at concentrations up to 1 μg/ml) for 24 h, and PCNA protein expression was determined by immunoblot analysis (12, 16). The comparability of the protein loaded was normalized to β-actin. The intensity of the bands was determined by scanning video densitometry using the phosphoimager (Storm 860, Amersham Biosciences) with ImageQuant TLV 2003.02.

Intracellular Signaling Pathways

FOXO1.

FOXO1 phosphorylation was assessed in MCCLs after treatment with rPGRN (at concentrations up to 1 μg/ml) using a commercially available EIA kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), and data analysis was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The acetylation level of FOXO1 was assessed by immunoblot analysis using an acetylated FOXO1-specific antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and the band intensity was normalized to total FOXO1 expression. The subcellular location of FOXO1 was assessed by immunohistochemistry (12) in liver sections from sham and BDL mice and by immunofluorescence (12) in MCCLs after incubation with 1 μg/ml rPGRN for 4 h, using an antibody specific to total FOXO1. For immunofluorescence, cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and images were taken on an Olympus IX-71 inverted confocal microscope.

Sirt1.

Sirt1 expression was assessed in isolated cholangiocytes from sham and BDL mice and in MCCLs after stimulation with various concentrations of rPGRN for 24 h by immunoblot analysis as described above (14). Sirt1 immunoreactivity was also assessed in liver sections from mice treated with rPGRN for 3 days by immunohistochemistry.

To assess the role of Sirt1 in PGRN-induced cholangiocyte proliferation, MCCLs were stably transfected with an expression vector containing mouse Sirt1 cDNA (pCMV-Sirt1) following previously described methodology (13). Relative Sirt1 expression was assessed by real-time PCR, and the resulting cell lines were designated as MCCL-Sirt1+ and MCCL-pCMV (mock-transfected control). The effect of rPGRN on proliferation of these cell lines was then assessed by cell counting experiments (16). Specifically, cell lines were plated in six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. The number of cells was counted in 6 nonoverlapping fields/well immediately before the addition of rPGRN (1 μg/ml) and again 24 h after stimulation. Data are expressed as average numbers of cells per field after each treatment. The role of Sirt1 expression on the rPGRN-induced subcellular location of FOXO1 was also assessed in MCCL-Sirt1+ and MCCL-pCMV by immunofluorescence as described above.

Effects of PGRN Suppression on Cholangiocyte Proliferation

To assess the role of PGRN expression in cholangiocyte proliferation in vitro, we stably transfected SureSilencing shRNA plasmids for mouse PGRN (SABiosciences) containing a marker for neomycin resistance into MCCLs following previously described methodology (13). The efficiency of PGRN knockdown was assessed by real-time PCR and immunoblot analysis. The resulting cell lines were designated as MCCL-PGRN shRNA and MCCL-neo neg (mock-transfected control). The effect of PGRN knockdown on proliferation was assessed by determining the levels of PCNA protein expression as a marker of proliferative capacity as described above.

In vivo, mice were pretreated with either PGRN-specific Vivo-Morpholinos (5′- CATCTGGCGGTCAGCTCCAGGACTA-3′) or a mismatched control Vivo-Morpholino sequence with six altered bases (underlined: 5′-CATGTCGCGCTCACCTCCACGACTA-3′, 10 mg·kg−1·day−1) via a tail vein for 1 day before either sham or BDL surgery. Treatment with Vivo-Morpholinos continued daily for 3 days postsurgery. The relative expression of PGRN was assessed by real-time PCR on RNA extracted from the total liver. The effect of in vivo suppression of PGRN expression on cholangiocyte proliferation was assessed as described above.

Statistical Analysis

For data exhibiting a normal distribution, differences between the two groups were analyzed by Student's unpaired t-test or ANOVA when more than two groups were analyzed, followed by the appropriate post hoc test. When the normality test failed, a Mann-Whitney U-test was performed when two groups were compared and Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA by ranks was performed when three or more groups were compared. In each case, P values of <0.05 were used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

PGRN Expression and Secretion Increase After BDL

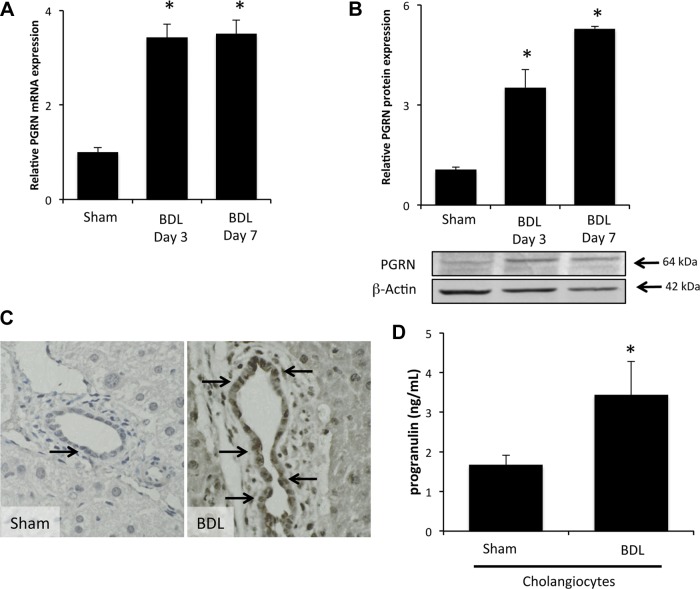

Expression of PGRN mRNA and protein was significantly upregulated in proliferating cholangiocytes 3 and 7 days after BDL compared with sham control surgery (Fig. 1, A and B). Immunohistochemical analysis of PGRN expression demonstrated that most PGRN immunoreactivity was found in the cholangiocytes, with weaker expression in the surrounding hepatocytes (Fig. 1C). This was supported by real-time PCR demonstrating that PGRN mRNA expression was highest in isolated cholangiocytes, to a lesser extent in hepatocytes, and virtually absent in hepatic stellate cells, vascular endothelial cells, or sinusoidal endothelial cells (data not shown). No change in circulating PGRN could be detected in the serum of mice after BDL surgery (data not shown). However, there was an increased level of PGRN in the conditioned media of cholangiocytes isolated after BDL surgery compared with sham surgery, suggesting increased local secretion of PGRN (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Progranulin (PGRN) expression and secretion are increased in proliferating cholangiocytes. A and B: PGRN expression was assessed in cholangiocytes isolated from sham-operated (sham) and bile duct ligated (BDL) mice 3 and 7 days after surgery by real-time PCR (A) and immunoblot analysis. Data are expressed as averages ± SE; n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with PGRN in cholangiocytes from sham mice. C: PGRN levels were also assessed in liver sections by immunohistochemistry. Magnification: ×40. D: PGRN levels in the supernatants of cell suspensions of freshly isolated cholangiocytes from sham and BDL mice were determined by EIA. Data are expressed as average PGRN concentrations (in ng/ml) ± SE; n = 3. *P < 0.05 compared with PGRN levels secreted from sham cells.

PGRN Increases Cholangiocyte Proliferation

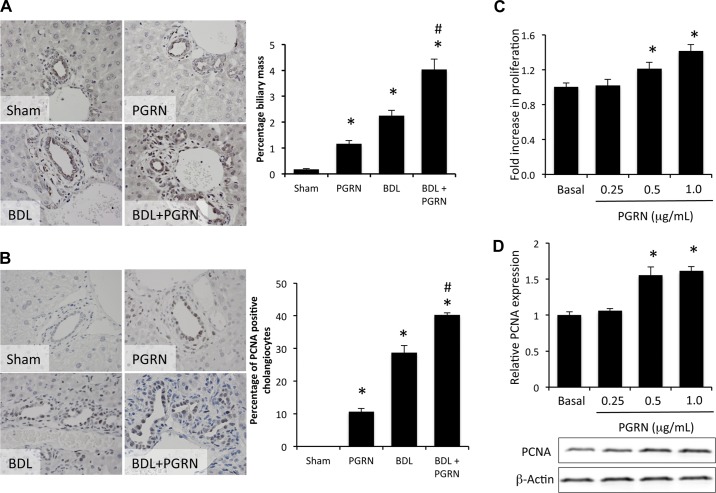

To determine the consequences of PGRN on cholangiocyte proliferation, we treated BDL and control mice with rPGRN for 3 days. Treatment with rPGRN in vivo increased biliary mass in sham mice and enhanced the increase in biliary mass observed after BDL (using CK-7 as a cholangiocyte marker; Fig. 2A). In parallel, systemic treatment with rPGRN in vivo induced cholangiocyte proliferation (as demonstrated by PCNA as a marker of proliferative capacity) in sham animals and enhanced the proliferative response of cholangiocytes to BDL surgery (Fig. 2B). To determine if PGRN exerts its proliferative effects directly on cholangiocytes or via some other indirect mechanism, we performed in vitro experiments on MCCLs. rPGRN increased cholangiocyte proliferation (Fig. 2C) and PCNA expression (Fig. 2D) in MCCLs, suggesting that PGRN exerts its proliferative effects directly on cholangiocytes.

Fig. 2.

PGRN stimulates cholangiocyte proliferation. Sham and BDL mice were treated systemically with recombinant (r)PGRN for 3 days. A and B: measurements of the number of cytokeratin (CK)-7-positive cholangiocytes (A) and PCNA-positive cholangiocytes (B) in liver sections (indicated by arrows) were performed. Data are expressed as averages ± SE; n = 7. *P < 0.05 compared with sham surgery; #P < 0.05 compared with BDL surgery. C and D: in vitro, cells from the mouse cholangiocyte cell line (MCCLs) were treated with various concentrations of rPGRN, and cell proliferation was assessed using a MTS cell proliferation assay (C) or by assessing PCNA expression by immunoblot analysis (D). Data are expressed as fold changes in proliferation (averages ± SE); n = 7. *P < 0.05 compared with basal treatment.

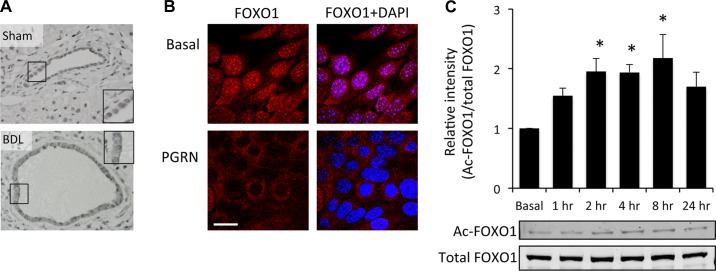

We (16) have previously shown that PGRN exerts its proliferative effects on cholangiocarcinoma cells via a mechanism involving nuclear extrusion of FOXO1; therefore, we wished to determine if this also occurs during hyperplastic cholangiocyte proliferation. FOXO1 immunoreactivity was found predominantly in the nucleus of cholangiocytes in sham mice but appeared to translocate to the cytoplasm after BDL surgery (Fig. 3A). In vitro, FOXO1 was predominately observed in the nucleus of MCCLs under basal conditions but was extruded to the cytoplasm after treatment with rPGRN (Fig. 3B). To determine what posttranslational modification of FOXO1 could be associated with the nuclear extrusion, we assessed phosphorylation and acetylation levels of FOXO1. Unlike in malignant cholangiocytes (16), we observed no significant difference in the phosphorylation of FOXO1 after PGRN treatment (data not shown). However, acetylation levels of FOXO1 significantly increased 2 h after PGRN treatment (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the cytoplasmic accumulation of FOXO1 may be a result of increased acetylation.

Fig. 3.

PGRN increases FOXO1 acetylation and nuclear extrusion. A: the subcellular location of FOXO1 was assessed in liver sections from sham and BDL mice by immunohistochemistry. Insets in each photomicrograph are higher-magnification images of the area indicated by the black boxes in A. B: in vitro, MCCLs were treated with rPGRN for 4 h, and the subcellular location of FOXO1 was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. FOXO1 immunoreactivity is shown in red, and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. C: relative acetylation levels of FOXO1 were assessed in MCCLs treated with rPGRN for various time points up to 24 h by immunoblot analysis using an acetylated (Ac) FOXO1-specific antibody. Samples were normalized to total FOXO1 expression. Data are expressed as relative acetylated FOXO1 protein expression (averages ± SE); n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with basal levels.

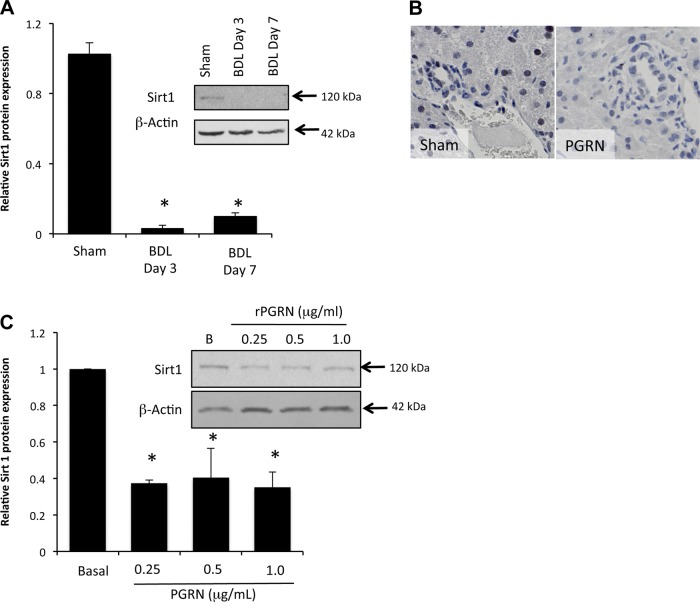

Acetylation levels of FOXO1 are under the tight control of Sirt1, which has been shown to deacetylate FOXO1 (36, 38, 44). Therefore, we assessed the expression levels of Sirt1 in cholangiocytes after BDL surgery and after rPGRN treatment. Sirt1 protein expression was dramatically suppressed in cholangiocytes isolated from mice 3 and 7 days after BDL surgery compared with sham control surgery (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, treatment of cholangiocytes with rPGRN decreased Sirt1 protein expression in vitro (Fig. 4B) and decreased Sirt1 immunoreactivity in cholangiocytes and hepatocytes in vivo (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) expression is decreased in proliferating cholangiocytes. A and B: Sirt1 expression was assessed in isolated cholangiocytes from sham and BDL mice (A) and in MCCLs treated in vitro with various concentrations of rPGRN for 4 h by immunoblot analysis (B). Data are expressed as relative protein expression (averages ± SE); n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with sham cholangiocytes. C: Sirt1 immunoreactivity was also assessed in liver sections from mice treated with rPGRN by immunohistochemistry. Magnification: ×40.

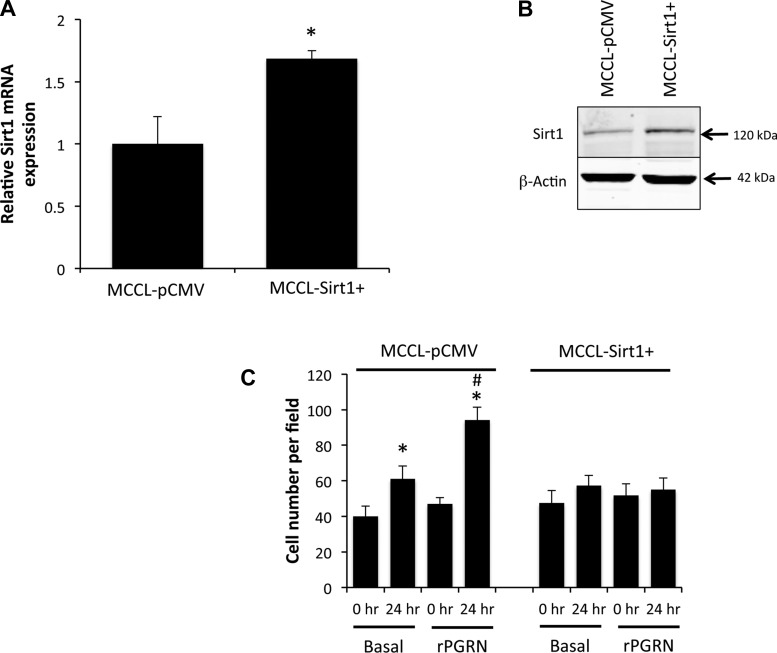

To evaluate the role of Sirt1 in the effects of PGRN on cell proliferation, we stably transfected an expression vector containing Sirt1 cDNA. The resulting cell line (MCCL-Sirt1+) had a modest increase in Sirt1 mRNA and protein expression compared with the mock-transfected control cell line (MCCL-pCMV; Fig. 5, A and B). Unlike MCCL-pCMV cells, treatment of MCCL-Sirt1+ cells with rPGRN failed to result in the cytoplasmic accumulation of FOXO1 (data not shown) and did not increase cell proliferation (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these data suggest that Sirt1 is important for the downstream regulation of FOXO1 activity and the subsequent growth-promoting effects of PGRN on cell proliferation.

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of Sirt1 prevented the proliferative effects of PGRN. A and B: MCCLs were stably transfected with a Sirt1 expression vector, and the relative levels of Sirt1 were assessed in the resulting cell line (MCCL-Sirt1+) and mock-transfected control cell line (MCCL-pCMV) by real-time PCR (A) and immunoblot analysis (B). Real-time PCR data are expressed as averages ± SE; n = 4. *P < 0.05. C: the effects of rPGRN treatment on MCCL-pCMV and MCCL-Sirt1+ cells were assessed by counting the number of cells in six nonoverlapping fields immediately before stimulation and then again 24 h later. Data are expressed as fold increases in cell numbers per field (averages ± SE). *P < 0.05.

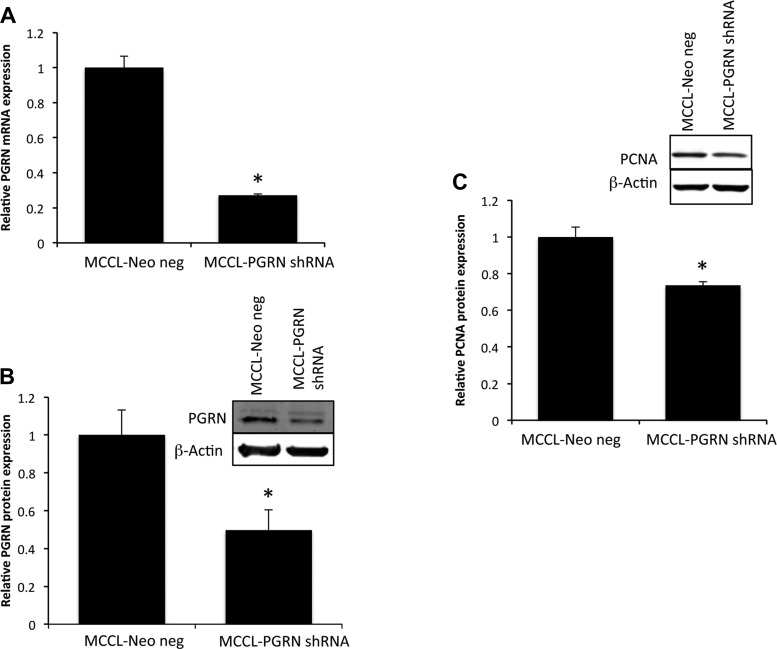

Cholangiocyte Proliferation Can Be Dampened by Suppression of PGRN Expression

To determine the effects of suppressed PGRN expression on cholangiocyte proliferation, we stably transfected MCCLs with a PGRN-specific shRNA sequence. The resulting cell line had a 75% reduction in PGRN mRNA expression (Fig. 6A) and a parallel suppression in PGRN protein expression (Fig. 6B). MCCL-PGRN shRNA cells had a modest but significant decrease in PCNA expression as a marker of proliferative capacity of these cells (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of PGRN expression in vitro reduces the cholangiocyte proliferative capacity. A and B: MCCLs were stably transfected with PGRN short hairpin (sh)RNA, and the relative levels of PGRN were assessed in the resulting cell line (MCCL-PGRN shRNA) and mock-transfected control cell line (MCCL-Neo neg) by real-time PCR (A) and immunoblot analysis (B). Real-time PCR data are expressed as averages ± SE; n = 4. *P < 0.05. Immunoblot data are expressed as relative protein expression (averages ± SE); n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with MCCL-Neo neg after β-actin normalization. C: the effects of PGRN knockdown on PCNA expression (as a marker of proliferative capacity) were assessed by immunoblot analysis. Data are expressed as relative PCNA protein expression (averages ± SE); n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with PCNA in MCCL-Neo neg cells.

In vivo, PGRN expression was suppressed using Vivo-Morpholino technology. PGRN Vivo-Morpholino treatment suppressed PGRN protein expression to ∼50% of control values in sham mice and prevented the increase in PGRN protein expression observed after BDL compared with sham control surgery (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis showed that PGRN Vivo-Morpholino treatment appeared to be similarly effective in inhibiting PGRN protein expression in cholangiocytes and hepatocytes (Fig. 7B). Suppression of PGRN expression prevented the increase in biliary mass normally observed after BDL surgery (Fig. 7, B and C) and decreased the percentage of PCNA-positive cholangiocytes observed after BDL (Fig. 7, B and D).

Fig. 7.

Suppression of PGRN expression in vivo inhibits biliary outgrowth after BDL. A and B: sham and BDL mice were treated with PGRN Vivo-Morpholino (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) or mismatched control Vivo-Morpholino for 4 days, and relative PGRN expression was assessed by immunoblot analysis (A) and immunohistochemistry (B). *P < 0.05 compared with sham surgery; #P < 0.05 compared with BDL surgery. C and D: measurements of the numbers of CK-7-positive cholangiocytes (C) and PCNA-positive cholangiocytes (D) in liver sections were performed. Data are expressed as averages ± SE; n = 7. *P < 0.05 compared with BDL surgery.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study relate to the consequences of increased PGRN expression on hyperplastic cholangiocyte proliferation. We demonstrated that 1) PGRN expression and secretion are increased in proliferating cholangiocytes after BDL surgery, 2) PGRN exerts proliferative effects on cholangiocytes via the downregulation of Sirt1 expression and subsequent increase in acetylation and cytoplasmic accumulation of FOXO1, and 3) suppression of PRGN expression inhibited the proliferation of hyperplastic cholangiocytes observed after BDL. These data suggest that the upregulation of PGRN may be a key feature stimulating cholangiocyte proliferation and that modulating PGRN levels may be a viable target for the development of treatment strategies that regulate the balance between cholangiocyte proliferation and ductopenia observed during cholestatic liver diseases.

Cholangiocyte proliferation is coordinately regulated by a number of growth factors, hormones, and neuropeptides during normal and cholestatic states via both autocrine and paracrine signaling (7, 8, 18–20). For example, nerve growth factor and VEGF both increase cholangiocyte proliferation in rodent models of cholestasis via autocrine mechanisms (19, 20). The data presented here support a role for yet another growth factor in the regulation of cholangiocyte proliferation. However, as mentioned previously, there exists a differential proliferative response with respect to the type and location on the biliary tree of the target cholangiocytes depending on the insult and/or factor administered (1, 2, 5, 17, 32, 33). The target subset of cholangiocytes that proliferate in response to growth factors such as nerve growth factor and VEGF are unclear. Similarly, our data demonstrate an increase in biliary mass after PGRN treatment in normal conditions as well as after BDL, where only large cholangiocytes proliferate (2). Therefore, it is unclear as to which subpopulation of cholangiocytes is responsive to PGRN, warranting further investigation. In addition to cholangiocytes, PGRN has been found to be a novel chondrogenic growth factor (40) and neurotrophic factor (41), and its overexpression also confers an aggressive phenotype on a number of tumor cells (27). We demonstrated that PGRN is expressed in both cholangiocytes and hepatocytes and that the PGRN Vivo-Morpholino treatment appeared to be similarly effective in inhibiting PGRN protein expression in both cell types. Therefore, the involvement of hepatocyte-derived PGRN in the regulation of cholangiocyte proliferation in our model cannot be ruled out.

The data presented here indicate that PGRN exerts its proliferative effects via a mechanism involving the suppression of Sirt1 expression and a subsequent increase in acetylation and cytoplasmic accumulation of FOXO1. Furthermore, we demonstrate that restoration of Sirt1 expression in our stably transfected MCCL-Sirt1+ cell line prevented the proliferative effects of PGRN on cholangiocytes in vitro. In support of our data, a decrease in Sirt1 expression has recently been shown in total liver extracts from BDL rats, which the authors linked to a failure in mitochondrial biogenesis leading to mitochondrial dysfunction (9). To our knowledge, our data demonstrating that Sirt1 expression is specifically downregulated in isolated cholangiocytes after BDL, which can be linked to increased cholangiocyte proliferation, represents the first indication that Sirt1 may play a role in the balance between cholangiocyte proliferation and loss observed during the course of cholestatic liver diseases.

In the present study, we demonstrated that a downstream consequence of Sirt1 suppression is increased acetylation, cytoplasmic accumulation, and, hence, inhibition of FOXO1, which is consistent with our current knowledge of how the FOXO transcription factor family is regulated (28). FOXO1 is known to regulate the expression of genes that regulate apoptosis and growth arrest (28). Agents shown to slow cell proliferation or increase apoptosis, such as resveratrol and camptothecin, do so via the activation of FOXO1 (11, 24). In support of the data presented here, we (16) have recently shown that PGRN exerts a proliferative effect on cholangiocarcinoma by the inhibition of FOXO1 activity. However, the nuclear extrusion of FOXO1 was as a result of the phosphorylation of FOXO1 by Akt (16) rather than by the increased acetylation demonstrated here. One explanation for the difference in mechanism by which FOXO1 is inhibited may be due to the increased reliance on Akt signaling by cholangiocarcinoma compared with their nonmalignant counterparts (29, 30, 42).

Cholestatic liver diseases such as primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis share a close association with liver inflammation (10, 25). In support of our data demonstrating an upregulation of PGRN expression in a mouse model of cholestasis, PGRN has previously been shown to be upregulated in a number of other disease states associated with inflammation, such as wound healing, tissue repair, and inflammatory arthritis (23, 26, 40, 45). Indeed, we (16) have recently demonstrated that PGRN expression and secretion are significantly increased in cholangiocarcinoma, a disease that has been shown to involve chronic upregulation of inflammatory cytokines (22, 37, 43). We (16) demonstrated that this PGRN upregulation was via a mechanism stimulated by IL-6, although whether this pathway is also responsible for the upregulation of PGRN expression after BDL is not known.

In conclusion, the data presented in this study indicate that PGRN expression and secretion are upregulated in cholangiocytes in a rodent model of cholestasis. PGRN then has growth-promoting properties on cholangiocytes via a decrease in the expression of the deacetylase Sirt1 and a subsequent increase in acetylation, nuclear extrusion, and inhibition of FOXO1 transcriptional activity. Taken together, our data indicate that PGRN expression and the subsequent signal transduction pathway may be a key mechanism in controlling cholangiocyte proliferation. Modulation of PGRN activity may represent a way to control the fine balance between cholangiocyte proliferation and apoptosis as a therapeutic option for maintaining biliary mass during cholestatic liver diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants K01-DK-078532, R03-DK-088012, and R01-DK-082435 (to S. DeMorrow) and by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for the Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-In-Aid for Scientific Research C-21590822 (to Y. Ueno).

This material is the result of work supported with the resources and use of facilities of the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (Temple, TX).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: G.F., Y.U., M.M., H.Y.P., C.G., and S.D. performed experiments; G.F., Y.U., M.Q., H.Y.P., C.G., and S.D. analyzed data; G.F., M.Q., M.M., D.L.-I., and S.D. interpreted results of experiments; G.F., Y.U., M.Q., M.M., D.L.-I., and S.D. edited and revised manuscript; G.F., Y.U., M.Q., M.M., H.Y.P., C.G., D.L.-I., and S.D. approved final version of manuscript; S.D. conception and design of research; S.D. prepared figures; S.D. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Dr. Gianfranco Alpini for the isolation of mouse cholangiocytes, Anna Webb and the Texas A&M Health Science Center Integrated Microscopy and Imaging Laboratory for assistance with the confocal microscopy imaging, and the staff of the Department of Comparative Medicine of Scott & White Hospital for assistance with animal surgical models.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alpini G, Franchitto A, Demorrow S, Onori P, Gaudio E, Wise C, Francis H, Venter J, Kopriva S, Mancinelli R, Carpino G, Stagnitti F, Ueno Y, Han Y, Meng F, Glaser S. Activation of α1-adrenergic receptors stimulate the growth of small mouse cholangiocytes via calcium-dependent activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 2 and specificity protein 1. Hepatology 53: 628–639, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alpini G, Glaser SS, Ueno Y, Pham L, Podila PV, Caligiuri A, LeSage G, LaRusso NF. Heterogeneity of the proliferative capacity of rat cholangiocytes after bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 274: G767–G775, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alpini G, Prall R, LaRusso NF. The pathobiology of biliary epithelia. Liver Biol Pathobiol 4E: 421–435, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alpini G, Roberts S, Kuntz SM, Ueno Y, Gubba S, Podila PV, LeSage G, LaRusso NF. Morphological, molecular, and functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes from normal rat liver. Gastroenterology 110: 1636–1643, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alpini G, Ueno Y, Glaser SS, Marzioni M, Phinizy JL, Francis H, Lesage G. Bile acid feeding increased proliferative activity and apical bile acid transporter expression in both small and large rat cholangiocytes. Hepatology 34: 868–876, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alpini G, Ulrich C, Roberts S, Phillips JO, Ueno Y, Podila PV, Colegio O, LeSage G, Miller LJ, LaRusso NF. Molecular and functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes from rat liver after bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 272: G289–G297, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alvaro D, Alpini G, Onori P, Perego L, Svegliata Baroni G, Franchitto A, Baiocchi L, Glaser SS, Le Sage G, Folli F, Gaudio E. Estrogens stimulate proliferation of intrahepatic biliary epithelium in rats. Gastroenterology 119: 1681–1691, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alvaro D, Mancino MG, Glaser S, Gaudio E, Marzioni M, Francis H, Alpini G. Proliferating cholangiocytes: a neuroendocrine compartment in the diseased liver. Gastroenterology 132: 415–431, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arduini A, Serviddio G, Escobar J, Tormos AM, Bellanti F, Vina J, Monsalve M, Sastre J. Mitochondrial biogenesis fails in secondary biliary cirrhosis in rats leading to mitochondrial DNA depletion and deletions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G119–G127, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aron JH, Bowlus CL. The immunobiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Immunopathol 31: 383–397, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Q, Ganapathy S, Singh KP, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. Resveratrol induces growth arrest and apoptosis through activation of FOXO transcription factors in prostate cancer cells. PLos One 5: e15288, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeMorrow S, Francis H, Gaudio E, Ueno Y, Venter J, Onori P, Franchitto A, Vaculin B, Vaculin S, Alpini G. Anandamide inhibits cholangiocyte hyperplastic proliferation via activation of thioredoxin 1/redox factor 1 and AP-1 activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G506–G519, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeMorrow S, Francis H, Gaudio E, Venter J, Franchitto A, Kopriva S, Onori P, Mancinelli R, Frampton G, Coufal M, Mitchell B, Vaculin B, Alpini G. The endocannabinoid anandamide inhibits cholangiocarcinoma growth via activation of the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G1150–G1158, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeMorrow S, Glaser S, Francis H, Venter J, Vaculin B, Vaculin S, Alpini G. Opposing actions of endocannabinoids on cholangiocarcinoma growth: recruitment of Fas and Fas ligand to lipid rafts. J Biol Chem 282: 13098–13113, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Erion DM, Yonemitsu S, Nie Y, Nagai Y, Gillum MP, Hsiao JJ, Iwasaki T, Stark R, Weismann D, Yu XX, Murray SF, Bhanot S, Monia BP, Horvath TL, Gao Q, Samuel VT, Shulman GI. SirT1 knockdown in liver decreases basal hepatic glucose production and increases hepatic insulin responsiveness in diabetic rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11288–11293, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frampton G, Invernizzi P, Bernuzzi F, Pae HY, Quinn M, Horvat D, Galindo C, Huang L, McMillin M, Cooper B, Rimassa L, Demorrow S. Interleukin-6-driven progranulin expression increases cholangiocarcinoma growth by an Akt-dependent mechanism. Gut 61: 268–277, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Francis H, Glaser S, Demorrow S, Gaudio E, Ueno Y, Venter J, Dostal D, Onori P, Franchitto A, Marzioni M, Vaculin S, Vaculin B, Katki K, Stutes M, Savage J, Alpini G. Small mouse cholangiocytes proliferate in response to H1 histamine receptor stimulation by activation of the IP3/CaMK I/CREB pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C499–C513, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Francis H, Glaser S, Ueno Y, LeSage G, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Taffetani S, Marzioni M, Alvaro D, Venter J, Reichenbach R, Fava G, Phinizy JL, Alpini G. cAMP stimulates the secretory and proliferative capacity of the rat intrahepatic biliary epithelium through changes in the PKA/Src/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. J Hepatol 41: 528–537, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaudio E, Barbaro B, Alvaro D, Glaser S, Francis H, Ueno Y, Meininger CJ, Franchitto A, Onori P, Marzioni M, Taffetani S, Fava G, Stoica G, Venter J, Reichenbach R, De Morrow S, Summers R, Alpini G. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates rat cholangiocyte proliferation via an autocrine mechanism. Gastroenterology 130: 1270–1282, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gigliozzi A, Alpini G, Baroni GS, Marucci L, Metalli VD, Glaser SS, Francis H, Mancino MG, Ueno Y, Barbaro B, Benedetti A, Attili AF, Alvaro D. Nerve growth factor modulates the proliferative capacity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium in experimental cholestasis. Gastroenterology 127: 1198–1209, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glaser SS, Gaudio E, Rao A, Pierce LM, Onori P, Franchitto A, Francis HL, Dostal DE, Venter JK, DeMorrow S, Mancinelli R, Carpino G, Alvaro D, Kopriva SE, Savage JM, Alpini GD. Morphological and functional heterogeneity of the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Lab Invest 89: 456–469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goydos JS, Brumfield AM, Frezza E, Booth A, Lotze MT, Carty SE. Marked elevation of serum interleukin-6 in patients with cholangiocarcinoma: validation of utility as a clinical marker. Ann Surg 227: 398–404, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guo F, Lai Y, Tian Q, Lin EA, Kong L, Liu C. Granulin-epithelin precursor binds directly to ADAMTS-7 and ADAMTS-12 and inhibits their degradation of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. Arthritis Rheum 62: 2023–2036, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Han S, Wei W. Camptothecin induces apoptosis of human retinoblastoma cells via activation of FOXO1. Curr Eye Res 36: 71–77, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Biliary innate immunity in the pathogenesis of biliary diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 9: 83–90, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He Z, Bateman A. Progranulin (granulin-epithelin precursor, PC-cell-derived growth factor, acrogranin) mediates tissue repair and tumorigenesis. J Mol Med 81: 600–612, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. He Z, Ismail A, Kriazhev L, Sadvakassova G, Bateman A. Progranulin (PC-cell-derived growth factor/acrogranin) regulates invasion and cell survival. Cancer Res 62: 5590–5596, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang H, Tindall DJ. FOXO factors: a matter of life and death. Future Oncol 2: 83–89, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kobayashi S, Werneburg NW, Bronk SF, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ. Interleukin-6 contributes to Mcl-1 up-regulation and TRAIL resistance via an Akt-signaling pathway in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 128: 2054–2065, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leelawat K, Leelawat S, Narong S, Hongeng S. Roles of the MEK1/2 and AKT pathways in CXCL12/CXCR4 induced cholangiocarcinoma cell invasion. World J Gastroenterol 13: 1561–1568, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. LeSage G, Glaser S, Ueno Y, Alvaro D, Baiocchi L, Kanno N, Phinizy JL, Francis H, Alpini G. Regression of cholangiocyte proliferation after cessation of ANIT feeding is coupled with increased apoptosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G182–G190, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. LeSage GD, Glaser SS, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Phinizy JL, Rodgers R, Caligiuri A, Papa E, Tretjak Z, Jezequel AM, Holcomb LA, Alpini G. Acute carbon tetrachloride feeding induces damage of large but not small cholangiocytes from BDL rat liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G1289–G1301, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mancinelli R, Franchitto A, Gaudio E, Onori P, Glaser S, Francis H, Venter J, Demorrow S, Carpino G, Kopriva S, White M, Fava G, Alvaro D, Alpini G. After damage of large bile ducts by γ-aminobutyric acid, small ducts replenish the biliary tree by amplification of calcium-dependent signaling and de novo acquisition of large cholangiocyte phenotypes. Am J Pathol 176: 1790–1800, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mano Y, Ishii M, Kisara N, Kobayashi Y, Ueno Y, Kobayashi K, Hamada H, Toyota T. Duct formation by immortalized mouse cholangiocytes: an in vitro model for cholangiopathies. Lab Invest 78: 1467–1468, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marzioni M, Glaser SS, Francis H, Phinizy JL, LeSage G, Alpini G. Functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes. Semin Liver Dis 22: 227–240, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, Kamel C, Chen D, Gu W, Bultsma Y, McBurney M, Guarente L. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell 116: 551–563, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park J, Tadlock L, Gores GJ, Patel T. Inhibition of interleukin 6-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation attenuates growth of a cholangiocarcinoma cell line. Hepatology 30: 1128–1133, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qiang L, Banks AS, Accili D. Uncoupling of acetylation from phosphorylation regulates FoxO1 function independent of its subcellular localization. J Biol Chem 285: 27396–27401, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roberts SK, Ludwig J, LaRusso NF. The pathobiology of biliary epithelia. Gastroenterology 112: 269–279, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tang W, Lu Y, Tian QY, Zhang Y, Guo FJ, Liu GY, Syed NM, Lai Y, Lin EA, Kong L, Su J, Yin F, Ding AH, Zanin-Zhorov A, Dustin ML, Tao J, Craft J, Yin Z, Feng JQ, Abramson SB, Yu XP, Liu CJ. The growth factor progranulin binds to TNF receptors and is therapeutic against inflammatory arthritis in mice. Science 332: 478–484, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Damme P, Van Hoecke A, Lambrechts D, Vanacker P, Bogaert E, van Swieten J, Carmeliet P, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W. Progranulin functions as a neurotrophic factor to regulate neurite outgrowth and enhance neuronal survival. J Cell Biol 181: 37–41, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu X, Kobayashi S, Qiao W, Li C, Xiao C, Radaeva S, Stiles B, Wang RH, Ohara N, Yoshino T, LeRoith D, Torbenson MS, Gores GJ, Wu H, Gao B, Deng CX. Induction of intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma by liver-specific disruption of Smad4 and Pten in mice. J Clin Invest 116: 1843–1852, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yokomuro S, Tsuji H, Lunz JG, 3rd, Sakamoto T, Ezure T, Murase N, Demetris AJ. Growth control of human biliary epithelial cells by interleukin 6, hepatocyte growth factor, transforming growth factor beta1, and activin A: comparison of a cholangiocarcinoma cell line with primary cultures of non-neoplastic biliary epithelial cells. Hepatology 32: 26–35, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhu WG. Applications of post-translational modifications of FoxO family proteins in biological functions. J Mol Cell Biol 3: 276–282, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu J, Nathan C, Jin W, Sim D, Ashcroft GS, Wahl SM, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wright CD, Ding A. Conversion of proepithelin to epithelins: roles of SLPI and elastase in host defense and wound repair. Cell 111: 867–878, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]