Abstract

Obese individuals typically exhibit a reduced capacity for metabolic flexibility by failing to increase fatty acid oxidation (FAO) upon the imposition of a high-fat diet (HFD). Exercise training increases FAO in the skeletal muscle of obese individuals, but whether this intervention can restore metabolic flexibility is unclear. The purpose of this study was to compare FAO in the skeletal muscle of lean and obese subjects in response to a HFD before and after exercise training. Twelve lean (means ± SE) (age 21.8 ± 1.1 yr, BMI 22.6 ± 0.7 kg/m2) and 10 obese men (age 22.4 ± 0.8 yr, BMI 33.7 ± 0.7 kg/m2) consumed a eucaloric HFD (70% of energy from fat) for 3 days. After a washout period, 10 consecutive days of aerobic exercise (1 h/day, 70% V̇o2peak) were performed, with the HFD repeated during days 8–10. FAO and indices of mitochondrial content were determined from muscle biopsies. In response to the HFD, lean subjects increased complete FAO (27.3 ± 7.4%, P = 0.03) in contrast to no change in their obese counterparts (1.0 ± 7.9%). After 7 days of exercise, citrate synthase activity and FAO increased (P < 0.05) regardless of body habitus; addition of the HFD elicited no further increase in FAO. These data indicate that obese, in contrast to lean, individuals do not increase FAO in skeletal muscle in response to a HFD. The increase in FAO with exercise training, however, enables the skeletal muscle of obese individuals to respond similarly to their lean counterparts when confronted with short-term excursion in dietary lipid.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, fat oxidation, mitochondria, physical activity

the prevalence of obesity has been increasing rapidly and is strongly associated with the development of insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes (10). An important indicator of metabolic health is metabolic flexibility, which is the ability to adjust substrate utilization to changes in substrate availability (16). For example, in lean individuals, fatty acid oxidation (FAO) at the whole body level increases with the imposition of a high-fat diet (HFD); to the contrary, obese individuals display an impaired capacity to increase FAO in the face of an elevation in dietary lipid (1, 11, 15, 21). In the skeletal muscle of lean individuals, a HFD also increased the transcription of genes involved in fatty acid transport and oxidation in contrast to minimal or no changes in their obese counterparts (3, 6, 20). This inability to increase FAO when lipid presence is elevated creates a condition of positive fat balance, which in skeletal muscle may lead to ectopic lipid accumulation (21), lipid peroxidation (23), and excessive increases in lipid intermediates such as diacylglycerol and ceramide, resulting in intracellular lipotoxicity (18).

Our research has demonstrated that obese and formerly severely obese (BMI >40 kg/m2) individuals who lost weight increased lipid oxidation in skeletal muscle to the same extent as lean subjects with 10 days of endurance-oriented exercise training (2). However, it is not evident whether exercise training restores metabolic flexibility with respect to adjusting appropriately (i.e., similar to lean subjects) to an increase in dietary lipid. The purposes of the present study were to determine 1) whether the skeletal muscle of young, obese individuals lacks metabolic flexibility in terms of increasing FAO in response to a HFD and 2) whether exercise training can correct any impairment in metabolic flexibility evident with obesity.

METHODS

Subjects.

Twelve lean (BMI ≤25 kg/m2) and 10 obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) male subjects aged 18–30 yr volunteered to participate. Subjects were not involved in an aerobic training program, as determined by a physical activity questionnaire and verbal questioning, and were asked to not change their physical activity patterns throughout the duration of the study. Participants filled out a medical history to confirm that they were free from disease, did not smoke, and were not taking any medications known to influence carbohydrate or lipid metabolism. Subjects were weight stable (± 2 kg over the past 3 mo) and nonsmokers. The experimental procedure and associated risks were explained in written and oral format, and informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the East Carolina Policy and Review Committee on Human Research and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design.

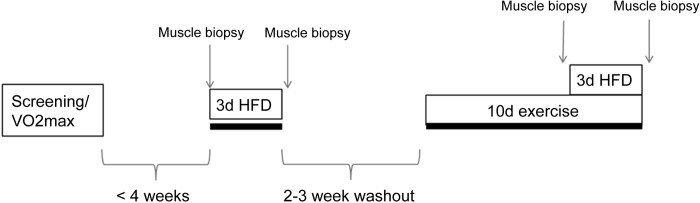

Each participant consumed a eucaloric HFD for 3 days while sedentary. After a 2- to 3-wk washout period, subjects exercised for 10 consecutive days and consumed a eucaloric HFD from days 8 to 10 of exercise training (Fig. 1). A 2-wk washout has been used in other studies examining the effects of a HFD and exercise (5, 27). Skeletal muscle biopsies were obtained from the vastus lateralis after a 12-h overnight fast on the morning that the HFD was initiated and on the morning after the 3 days of the HFD. Blood samples were taken at the initial screening and biopsy visits.

Fig. 1.

Study design. Subjects were screened and tested for maximal aerobic capacity (V̇o2max) before commencement of the study. Within 4 wk of screening, subjects underwent a fasting muscle biopsy of the vastus lateralis, consumed an isocaloric 70% high-fat diet (HFD) for 3 days (3d), and then had another muscle biopsy on the morning after the final day of the HFD. After a 2- to 3-wk washout period, subjects began exercise training for 10 consecutive days (10d), 1 h/day, at 70% peak oxygen consumption. On the morning of day 8, subjects had a muscle biopsy and began consuming the HFD during days 8–10 of exercise training. The day after the exercise training and second HFD was finished, subjects underwent their final muscle biopsy.

Diet.

The HFD consisted of ∼70% fat, 15% carbohydrate, and 15% protein and was calculated to be eucaloric and maintain body mass. In our preliminary studies, this fat proportion and duration (3 days) increased FAO in skeletal muscle by 38% in four lean subjects (data not shown), and another group reported that a similar diet increased pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) content and activity in skeletal muscle (20). Energy content for each individual was determined from the Harris-Benedict equation (13), and mean macronutrient content (per kg body mass) was 2.5 g/kg fat, 1.2 g/kg carbohydrate, and 1.0 g/kg protein; 21% of the energy intake from fat consisted of saturated fats. Subjects were weighed before and after the HFD and at the beginning of exercise training to ensure that body weight did not change throughout the duration of the study. The 3-day diet regimen was described to each subject in detail, emphasizing the importance of consuming only the items indicated. Some meals were from fast-food chains, and subjects ordered the exact items and returned dated receipts to ensure compliance. The remainder of the food items were prepackaged and labeled in the appropriate amount for each given day and provided to the participants. Subjects logged their intake. On the day prior to commencement of the HFD, subjects were provided an isocaloric diet consisting of ∼25% fat, 15% protein, and 60% carbohydrates. All diets and food logs were analyzed by Nutritionist Pro Nutrition Analyst Software (Axxya Systems, Stafford, TX) to ensure correct macronutrient composition.

Exercise training.

An incremental maximal exercise test on an electronically braked cycle ergometer was performed to determine peak oxygen uptake (V̇o2peak) during the screening process. Participants then exercised 60 min/day at 70% V̇o2peak for 10 consecutive days. All training was supervised and performed in the laboratory setting; heart rate was monitored throughout each training session and V̇o2 measurements were taken periodically to ensure proper workload. Net energy utilized during exercise training was determined using indirect calorimetry and the resulting energy added to the diets during days 8–10 of exercise. Exercise was performed 14–18 h before the muscle biopsies on days 7 and 10.

Muscle analyses.

Fatty acid oxidation was measured as described previously (2, 14, 17). Briefly, 50–60 mg of muscle tissue was collected in 200 μl of a buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4. Samples were minced with scissors to remove excess fat and connective tissue and diluted 20-fold with additional buffer. Tissue was placed on ice and homogenized with a Teflon pestle for 30 s. Forty microliters of homogenate was added to the top well of a sealed, modified 48-well plate that contained a channel connecting to the adjacent trap well, which allowed for the passage of CO2 liberated by the complete oxidation of [1-14C]palmitate. The bottom trap well contained 1 N sodium hydroxide to collect the 14CO2 given off by the oxidation procedure. To initiate the reaction, 160 μl of a reaction buffer composed of the following was added to the top wells: 0.2 mM palmitate ([1-14C]palmitate at 0.5 μCi/ml), 100 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris·HCl, 5 mM potassium phosphate, 80 mM potassium chloride, 1 mM magnesium chloride, 0.1 mM malate, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM l-carnitine, 0.5 mM coenzyme A, and 0.5% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4. The samples were incubated in a 37°C water bath for 30 min, at which point 100 μl of 70% perchloric acid was added to terminate the reaction. The plate was placed on a shaker for 1 h to ensure complete transfer of CO2 into the bottom well. Label incorporation into 14CO2 was determined by scintillation counting using 4 ml of Uniscient BD (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA). Incomplete oxidative products (acid-soluble metabolites) remaining in the top well were measured as described previously (17).

A 10- to 15-mg piece of muscle was homogenized at 4°C using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY) in a lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 12 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 100 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS and supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were rotated end over end on a rotating wheel for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 21,000 g for 20 min at 10°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Five micrograms of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransfered to polyvinylidened flouride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and probed overnight for cytochrome c oxidase IV (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and with a cocktail containing antibodies against the following proteins (1:1,000): complex I subunit NDUFB8, complex II subunit 30 kDa, complex III subunit core 2, complex IV subunit II, and ATP synthase subunit-α (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR). Membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the corresponding secondary antibody, and the immunoreactive proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ChemiDoc XRS+ Imaging System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Samples were normalized to a crude muscle homogenate sample on each gel to normalize for blotting efficiency across gels.

A 10- to 15-mg piece of muscle was diluted 20-fold in a buffer containing 100 mM KH2PO4 and 0.05% bovine serum albumin and homogenized at 4°C using the Bullet Blender. Homogenates went through four freeze-thaw cycles before experimentation. This homogenate was used for determining citrate synthase (CS) and β-hydroxyacetyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (HAD) activity. Protein content was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay. CS activity was assessed with reagents provided in a kit (Sigma CS0720), which used a colorimetric reaction to measure the reaction rate of acetyl coenzyme A and oxaloacetic acid. Activity of HAD was measured using methods described previously (26), and rates were determined by calculating the rate of disappearance of NADH after the addition of acetoacetyl coenzyme A.

Statistical analyses.

Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to compare the data. Post hoc analyses were performed using contrast-contrast analysis. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05, and all data are expressed as means ± SE. Because of limitations in tissue size, all measurements could not be obtained for all individuals; the n for each variable is indicated.

RESULTS

Anthropometric data are presented in Table 1. Body mass, BMI, fasting insulin, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance were significantly higher in the obese subjects (P < 0.01). Blood lipids, glucose, and insulin did not change as a result of the HFD or exercise training and were not associated with FAO or mitochondrial content (data not shown). All subjects remained weight stable throughout the course of the study, and there were no changes in body mass in either group (data not shown). The diet composition was similar between lean and obese subjects (72% fat, 15% carbohydrate, and 13% protein) and provided a significant increase in dietary fat over their normal consumption determined from 3-day food logs performed before commencement of the study (35% fat, 48% carbohydrate, and 17% protein).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Lean (n = 12) | Obese (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 21.8 ± 1.1 | 22.4 ± 0.8 |

| Height, cm | 178.9 ± 2.0 | 179.1 ± 2.2 |

| Mass, kg | 72.2 ± 2.4 | 108.4 ± 3.3* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.6 ± 0.7 | 33.7 ± 0.7* |

| Body fat, % | 17.7 ± 1.8 | 37.5 ± 1.8* |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/l | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| Fasting insulin, ρmol/l | 44 ± 8 | 78 ± 8* |

| HOMA-IR | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3* |

| Plasma cholesterol, mmol/l | 3.97 ± 0.21 | 4.62 ± 0.31 |

| Plasma triglycerides, mmol/l | 0.82 ± 0.10 | 1.37 ± 0.19* |

| V̇o2peak, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 36.7 ± 1.2 | 27.2 ± 1.2* |

| V̇o2peak, l/min | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

Results are expressed as means ± SE. HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from lean.

Fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle.

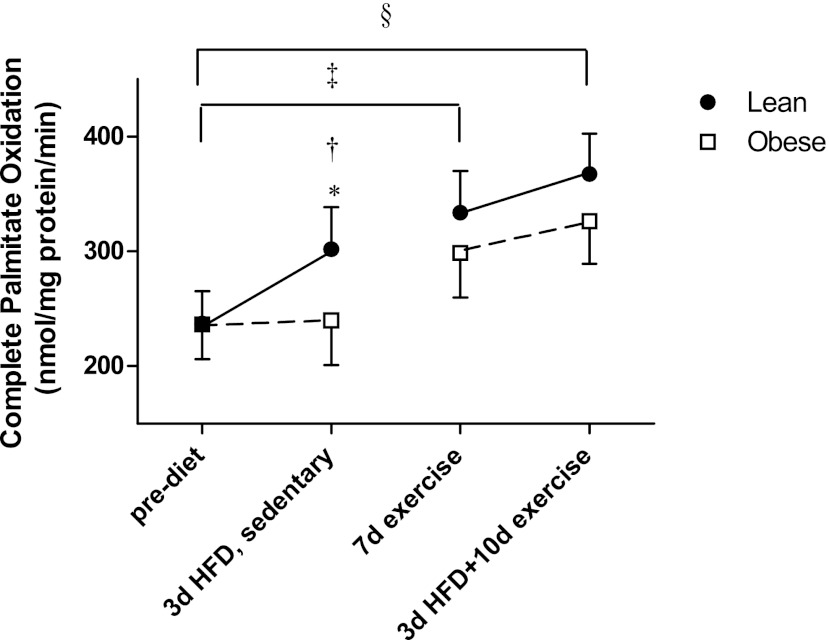

Fatty acid oxidation in response to the high-fat diet and exercise training are presented in Fig. 2. The lean subjects increased complete palmitate oxidation (14CO2 production) by 27% in response to the 3-day HFD (P = 0.03), indicating metabolic flexibility in response to an increase in dietary lipid. However, there was essentially no alteration in FAO in the obese group (1% increase vs. prediet values; Fig. 2), indicating a lack of metabolic flexibility. Exercise training (P = 0.02) and 10 days of exercise plus the 3-day HFD (P = 0.002) increased FAO above preexercise levels in both groups; however, in relation to metabolic flexibility, there was no significant increase in FAO with the addition of the HFD after the 7 days of exercise (Fig. 2). Total FAO (overall average 1,450.8 nmol·mg protein−1·min−1) and acid-soluble metabolites (overall average 1,157.3 nmol·mg protein−1·min−1) did not change with the HFD or exercise training and were not different between the lean and obese groups (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Complete palmitate oxidation (14CO2 production from palmitate) in skeletal muscle biopsies prediet, following a 3d HFD in the sedentary condition, after 7 days of exercise, and after a 3d HFD + 10d exercise in lean (n = 9) and obese (n = 8) men. Results are expressed as means ± SE. *Significantly different from obese after the 3d HFD (P = 0.02); †significantly increased compared with the prediet condition for lean (P = 0.02); ‡significant treatment effect for 7 days (7d) of exercise compared with the prediet condition (P = 0.02); §significant treatment effect for the 10d exercise + HFD compared with the prediet condition (P < 0.01).

Skeletal muscle enzyme activities/protein content.

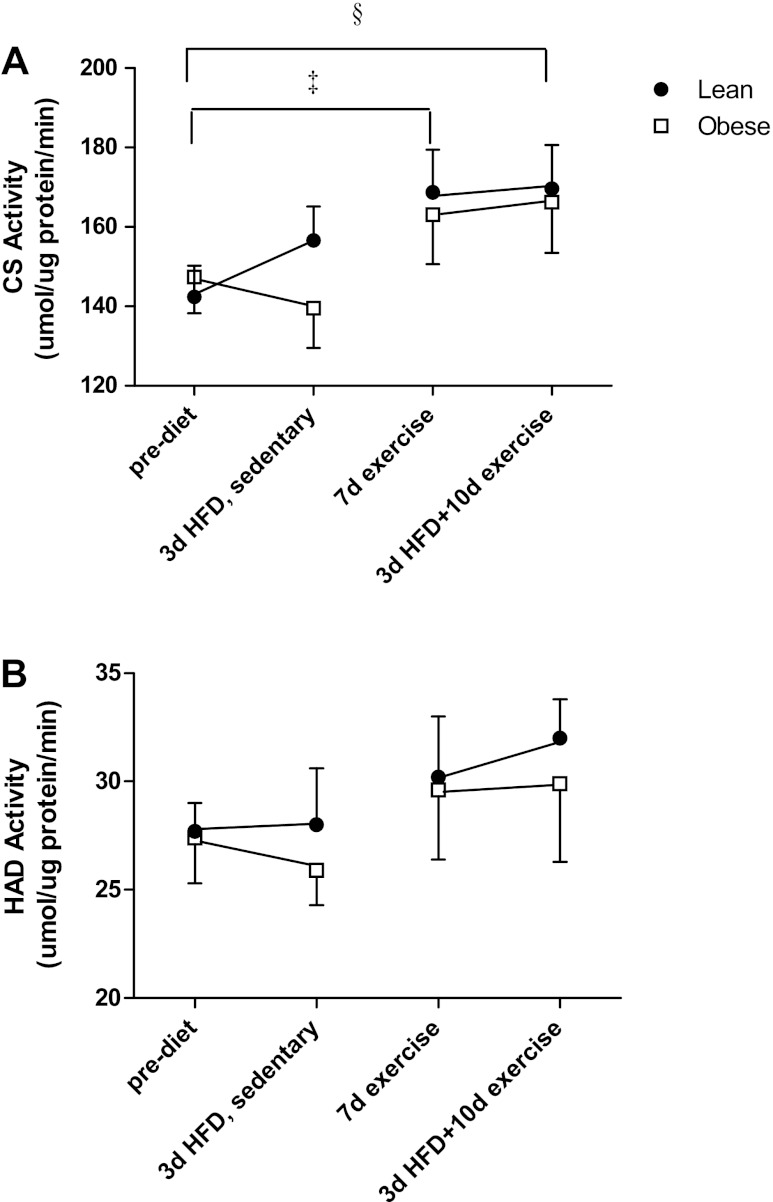

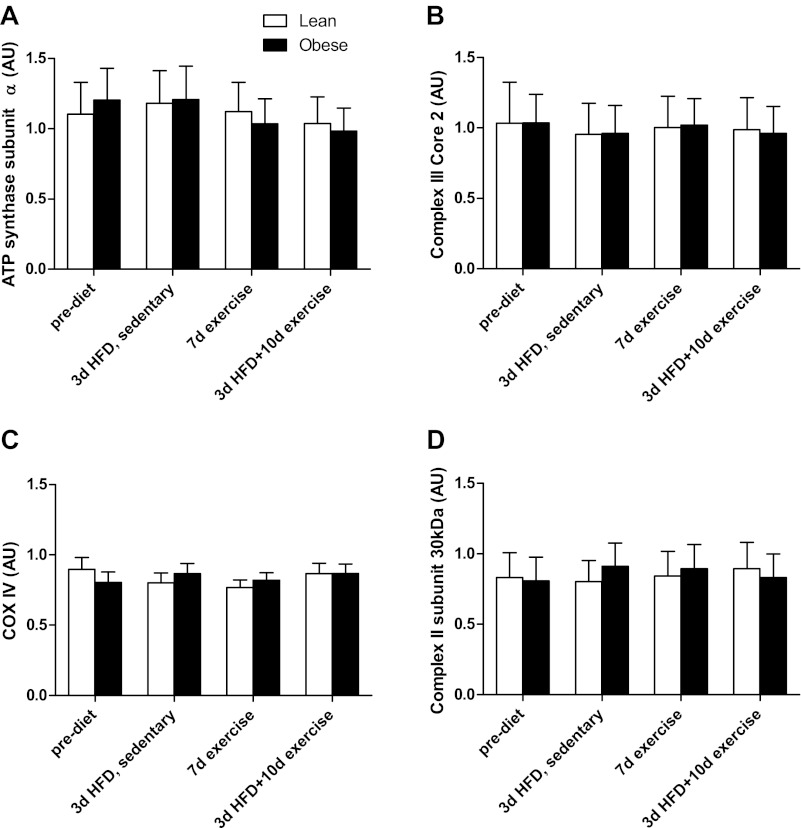

Enzyme activities for CS and HAD are presented in Fig. 3, A and B, respectively. In the sedentary state, CS activity exhibited a pattern similar to complete FAO (Fig. 2), with a tendency for the lean subjects to increase (12.3 ± 7.3%, P = 0.17) in response to the HFD and the obese subjects to have an attenuated response (−2.3 ± 8.9% decrease from prediet values). Seven days of exercise training increased CS activity in both groups over the sedentary condition (P = 0.02), with no further change at 10 days of exercise plus the HFD (P = 0.03 compared with sedentary prediet) (Fig. 3A). The trends for HAD responses to the HFD and exercise training were similar to CS, with a HFD plus exercise increase that approached statistical significance (P = 0.07 compared with sedentary prediet; Fig. 3B). Protein content of complexe II, III, and IV and ATP synthase subunits did not change with the HFD or exercise training and were not different between lean and obese individuals (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Citrate synthase (CS; A) and hydroxy coenzyme A dehydrogenase (HAD; B) prediet, after 3d HFD, after 7d exercise, and after 10d exercise + 3d HFD. CS activity was determined from 12 lean and 9 obese subjects, whereas HAD was determined from 10 lean and 8 obese subjects. Results are expressed as means ± SE. ‡Significant treatment effect for 7d exercise compared with the prediet condition (P = 0.02); §significant treatment effect for the 10d exercise + HFD compared with the prediet condition (P = 0.03).

Fig. 4.

Protein content of mitochondrial electron transport chain enzyme subunits prediet, after 3d HFD, after 7d exercise, and after 10d exercise + 3d HFD in 9 lean and 8 obese subjects. A: ATP synthase subunit-α. B: complex III core 2. C: cytochrome c oxidase IV (COX IV). D: complex II 30 kDa. Results are expressed as means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

A decrement in metabolic flexibility with obesity was first observed by Kelley et al. (15), who reported an inability to increase carbohydrate oxidation in response to euglycemic/hyperinsulinemic conditions. In terms of lipid availability, both whole body fat oxidation (1) and the transcription of genes regulating fat oxidation in skeletal muscle (3) increased in lean individuals, whereas their obese counterparts exhibited dampened responses with the imposition of a HFD. The ability to adjust FAO appropriately in response to excursions in dietary lipid is a critical component of metabolic health because inflexibility may lead to positive fat balance (11), ectopic lipid accumulation (29), and weight gain (21). In terms of intervention, FAO in skeletal muscle increases in both lean and obese individuals with relatively short-term (10-day) endurance-oriented exercise training (2); however, it is not evident whether exercise training can rescue (i.e., induce a response similar to that seen in lean subjects) the impairment in metabolic flexibility evident with obesity. The main findings of the present study were that 1) relatively young, obese individuals lack metabolic flexibility in terms of increasing FAO in skeletal muscle in response to a HFD and 2) exercise training increases FAO in skeletal muscle, which enables obese individuals to respond to an increase in dietary lipid in a manner similar to lean subjects.

In the current study the lean, but not obese, group increased complete FAO in skeletal muscle in response to the 3-day HFD (Fig. 2), which corresponds with other studies at the whole body level (1, 29). We have reported previously that obese individuals exhibited a diminished capacity to increase the expression of genes that regulate fatty acid transport and utilization in response to a HFD (3). The current findings provide the additional information that this impairment in gene expression with obesity likely contributes, at least in part, to the inability to upregulate FAO in the face of increased lipid availability (Fig. 2). However, although the patterns of change in CS, which can reflect mitochondrial content (30), and FAO were similar in the lean subjects (Figs. 2 and 3), it is likely that factors involved with enhanced mitochondrial function also contributed to the increases in FAO. PDK4, an enzyme that inhibits activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, responds rapidly to increases in lipid presence that would in turn partition substrates toward FAO (8). A HFD increased PDK4 protein content and overall PDK activity in lean individuals significantly after only 1 day (20), and PDK4 mRNA was increased in lean but not obese individuals after a 5-day 60% fat diet (3). Thus, an inability to increase PDK4 content with obesity may help explain the differential response to the HFD (Fig. 2); however, this is conjecture, because limitations in tissue size prevented us from determining PDK4 content. Also, one of the limitations of this study was that sufficient tissue could not be obtained for all analyses, which may have compromised the power for detecting statistical differences in measurements such as CS activity.

A novel feature of the current study was the inclusion of short-term aerobic exercise training as a possible means for improving metabolic flexibility. The 7 days of exercise training increased skeletal muscle FAO to the same extent in both groups of subjects (Fig. 2), indicative of no resistance to the intervention with obesity. Similar increases in FAO were reported in lean, obese, and post-gastric bypass subjects (2) and in lean and obese Caucasian and African-American women (9) with 10 days of exercise, suggesting that FAO in skeletal muscle increases rapidly regardless of body habitus. However, to our knowledge, no studies have directly examined the effect of exercise training on metabolic flexibility in relation to an increase in dietary lipid. We observed that with the addition of the HFD neither the lean nor obese groups significantly increased FAO above that which was evident after exercise training alone (Fig. 2); this lack of a response indicates technically that metabolic flexibility, i.e., the ability to increase FAO with respect to increased lipid availability, was not enhanced. However, it is important to note that exercise training increased FAO equivalent to or beyond the increment seen in response to the HFD alone (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that a high absolute capacity for FAO can render the skeletal muscle of the obese effective in dealing with increased dietary lipid and minimizing positive lipid balance, although an enhanced ability to adjust utilization (metabolic flexibility) per se is not evident.

With exercise training, CS and HAD activities mirrored the pattern of FAO changes, with CS activity elevated compared with the sedentary condition at both 7 and 10 days (Fig. 3). Endurance-oriented exercise training has been shown to be a potent means for rapidly (7–14 days) improving the maximal activity and content of mitochondrial proteins (4, 25, 28) in lean individuals. Although previous research in rodents have shown an additive effect of exercise training and a HFD on CS and HAD activities (7, 24), these enzymes did not change either with the addition of a HFD in endurance-trained humans (12) or in the present study (Fig. 3), implying either a species difference or that the increase in mitochondrial content with exercise training in humans is sufficient to adjust to subsequent increases in dietary lipid. Similarly, rats bred for high intrinsic running capacity had higher skeletal muscle lipid oxidation rates compared with their low intrinsic running capacity counterparts, which was due primarily to increased oxidative capacity and mitochondrial content in the white muscle fibers (22). However, the current data cannot dismiss the possibility that improvements in mitochondrial function also contributed to the enhanced capacity for FAO.

Electron transport chain content was not altered with the HFD or exercise training and did not differ with obesity (Fig. 4). The temporal pattern of gene expression likely varies, because Perry et al. (19) showed that CS and HAD activities increased after 6 days of training, whereas cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV content did not increase until 10 days. However, the training protocol of our study was moderate (1 h at 70% V̇o2peak) compared with the one employed by Perry et al. (19). Therefore, the higher intensity of the former may have elicited a more robust response in mitochondrial content compared with our study.

In conclusion, 3 days of a HFD increased lipid oxidation in the skeletal muscle of lean but not obese individuals, which was indicative of an impairment in metabolic flexibility with obesity. Endurance-oriented exercise training increased lipid oxidation and CS activity in skeletal muscle regardless of body habitus, with no incremental improvement with the addition of a HFD. These findings suggest that the increase in FAO in skeletal muscle with endurance-oriented exercise training enables obese individuals to respond similarly to their lean counterparts when confronted with an increase in dietary lipid intake.

GRANTS

Funding for this work was provided by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-056112, J. A. Houmard).

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.M.B. and J.A.H. did the conception and design of the research; G.M.B., D.Z., R.C.H., and J.A.H. performed the experiments; G.M.B. and D.Z. analyzed the data; G.M.B., D.Z., and J.A.H. interpreted the results of the experiments; G.M.B. and J.A.H. prepared the figures; G.M.B. and J.A.H. drafted the manuscript; G.M.B. and J.A.H. edited and revised the manuscript; G.M.B. and J.A.H. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Angela Clark and Rita Bowden for assisting with specimen collection and the undergraduate student assistants at East Carolina University for assisting with exercise training and testing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Astrup A, Buemann B, Christensen NJ, Toubro S. Failure to increase lipid oxidation in response to increasing dietary fat content in formerly obese women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 266: E592–E599, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berggren JR, Boyle KE, Chapman WH, Houmard JA. Skeletal muscle lipid oxidation and obesity: influence of weight loss and exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E726–E732, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyle KE, Canham JP, Consitt LA, Zheng D, Koves TR, Gavin TP, Holbert D, Neufer PD, Ilkayeva O, Muoio DM, Houmard JA. A high-fat diet elicits differential responses in genes coordinating oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle of lean and obese individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 775–781, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burgomaster KA, Cermak NM, Phillips SM, Benton CR, Bonen A, Gibala MJ. Divergent response of metabolite transport proteins in human skeletal muscle after sprint interval training and detraining. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1970–R1976, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burke LM, Angus DJ, Cox GR, Cummings NK, Febbraio MA, Gawthorn K, Hawley JA, Minehan M, Martin DT, Hargreaves M. Effect of fat adaptation and carbohydrate restoration on metabolism and performance during prolonged cycling. J Appl Physiol 89: 2413–2421, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cameron-Smith D, Burke LM, Angus DJ, Tunstall RJ, Cox GR, Bonen A, Hawley JA, Hargreaves M. A short-term, high-fat diet up-regulates lipid metabolism and gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Am J Clin Nutr 77: 313–318, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng B, Karamizrak O, Noakes TD, Dennis SC, Lambert EV. Time course of the effects of a high-fat diet and voluntary exercise on muscle enzyme activity in Long-Evans rats. Physiol Behav 61: 701–705, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chokkalingam K, Jewell K, Norton L, Littlewood J, van Loon LJ, Mansell P, Macdonald IA, Tsintzas K. High-fat/low-carbohydrate diet reduces insulin-stimulated carbohydrate oxidation but stimulates nonoxidative glucose disposal in humans: An important role for skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 284–292, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cortright RN, Sandhoff KM, Basilio JL, Berggren JR, Hickner RC, Hulver MW, Dohm GL, Houmard JA. Skeletal muscle fat oxidation is increased in African-American and white women after 10 days of endurance exercise training. Obesity (Silver Spring) 14: 1201–1210, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 288: 1723–1727, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galgani JE, Moro C, Ravussin E. Metabolic flexibility and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1009–E1017, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goedecke JH, Christie C, Wilson G, Dennis SC, Noakes TD, Hopkins WG, Lambert EV. Metabolic adaptations to a high-fat diet in endurance cyclists. Metabolism 48: 1509–1517, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris JA, Benedict FG. A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 4: 370–373, 1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jong-Yeon K, Hickner RC, Dohm GL, Houmard JA. Long- and medium-chain fatty acid oxidation is increased in exercise-trained human skeletal muscle. Metabolism 51: 460–464, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kelley DE, Goodpaster B, Wing RR, Simoneau JA. Skeletal muscle fatty acid metabolism in association with insulin resistance, obesity, and weight loss. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 277: E1130–E1141, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelley DE, Mandarino LJ. Fuel selection in human skeletal muscle in insulin resistance: a reexamination. Diabetes 49: 677–683, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim JY, Hickner RC, Cortright RL, Dohm GL, Houmard JA. Lipid oxidation is reduced in obese human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E1039–E1044, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moro C, Galgani JE, Luu L, Pasarica M, Mairal A, Bajpeyi S, Schmitz G, Langin D, Liebisch G, Smith SR. Influence of gender, obesity, and muscle lipase activity on intramyocellular lipids in sedentary individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 3440–3447, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perry CG, Lally J, Holloway GP, Heigenhauser GJ, Bonen A, Spriet LL. Repeated transient mRNA bursts precede increases in transcriptional and mitochondrial proteins during training in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 588: 4795–4810, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peters SJ, Harris RA, Wu P, Pehleman TL, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL. Human skeletal muscle PDH kinase activity and isoform expression during a 3-day high-fat/low-carbohydrate diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281: E1151–E1158, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ravussin E. Metabolic differences and the development of obesity. Metabolism 44: 12–14, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rivas DA, Lessard SJ, Saito M, Friedhuber AM, Koch LG, Britton SL, Yaspelkis BB, 3rd, Hawley JA. Low intrinsic running capacity is associated with reduced skeletal muscle substrate oxidation and lower mitochondrial content in white skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R835–R843, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Russell AP, Gastaldi G, Bobbioni-Harsch E, Arboit P, Gobelet C, Deriaz O, Golay A, Witztum JL, Giacobino JP. Lipid peroxidation in skeletal muscle of obese as compared to endurance-trained humans: a case of good vs. bad lipids? FEBS Lett 551: 104–106, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simi B, Sempore B, Mayet MH, Favier RJ. Additive effects of training and high-fat diet on energy metabolism during exercise. J Appl Physiol 71: 197–203, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spina RJ, Chi MM, Hopkins MG, Nemeth PM, Lowry OH, Holloszy JO. Mitochondrial enzymes increase in muscle in response to 7–10 days of cycle exercise. J Appl Physiol 80: 2250–2254, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Srere PA. Citrate synthase. In: Methods in Enzymology, edited by Lowenstein JM. New York: Academic, 1969, p. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stellingwerff T, Spriet LL, Watt MJ, Kimber NE, Hargreaves M, Hawley JA, Burke LM. Decreased PDH activation and glycogenolysis during exercise following fat adaptation with carbohydrate restoration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E380–E388, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Talanian JL, Galloway SD, Heigenhauser GJ, Bonen A, Spriet LL. Two weeks of high-intensity aerobic interval training increases the capacity for fat oxidation during exercise in women. J Appl Physiol 102: 1439–1447, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas CD, Peters JC, Reed GW, Abumrad NN, Sun M, Hill JO. Nutrient balance and energy expenditure during ad libitum feeding of high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 55: 934–942, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tunstall RJ, Mehan KA, Wadley GD, Collier GR, Bonen A, Hargreaves M, Cameron-Smith D. Exercise training increases lipid metabolism gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283: E66–E72, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]