Abstract

Candidate genes have been identified that confer increased risk for diabetic glomerulosclerosis (DG). Mice heterozygous for the Akita (Ins2+/C96Y) diabetogenic mutation with a second mutation introduced at the bradykinin 2 receptor (B2R−/−) locus express a disease phenotype that approximates human DG. Src homology 2 domain transforming protein 1 (p66) controls mitochondrial metabolism and cellular responses to oxidative stress, aging, and apoptosis. We generated p66-null Akita mice to test whether inactivating mutations at the p66 locus will rescue kidneys of Akita mice from disease-causing mutations at the Ins2 and B2R loci. Here we show null mutations at the p66 and B2R loci interact with the Akita (Ins2+/C96Y) mutation, independently and in combination, inducing divergent phenotypes in the kidney. The B2R−/− mutation induces detrimental phenotypes, as judged by increased systemic and renal levels of oxidative stress, histology, and urine albumin excretion, whereas the p66-null mutation confers a powerful protection phenotype. To elucidate the mechanism(s) of the protection phenotype, we turned to our in vitro system. Experiments with cultured podocytes revealed previously unrecognized cross talk between p66 and the redox-sensitive transcription factor p53 that controls hyperglycemia-induced ROS metabolism, transcription of p53 target genes (angiotensinogen, angiotensin II type-1 receptor, and bax), angiotensin II generation, and apoptosis. RNA-interference targeting p66 inhibits all of the above. Finally, protein levels of p53 target genes were upregulated in kidneys of Akita mice but unchanged in p66-null Akita mice. Taken together, p66 is a potential molecular target for therapeutic intervention in DG.

Keywords: Akita mouse, diabetic glomerulosclerosis, proteinuria, angiotensin II, apoptosis

the united states renal data systems list diabetic glomerulosclerosis (DG) as the leading cause of end stage renal disease (54). The observation that only 30–35% of the estimated 22 million Americans with diabetes mellitus (DM) will ever develop DG strongly suggests this disorder occurs in a subset of genetically at risk individuals. Candidate genes have been identified that confer increased risk for DG, including insertion/deletion polymorphisms in the angiotensin-1 converting enzyme (15) and, more recently, mutations at the bradykinin 2 receptor (B2R) locus (20, 21). The exponential increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) associated with DM (6, 40) serves as the catalyst for the expression of gene programs that orchestrate the remodeling of the diabetic kidney (23).

Src homology 2 domain containing transforming protein 1 (p66) controls mitochondrial metabolism and cellular responses to oxidative stress, aging, and apoptosis (4, 17, 35). Under stress stimuli, the activated p66 redox enzyme translocates to mitochondria, augmenting ROS production by binding and oxidizing cytochrome c to generate H2O2 (41). The p66 also increases ROS production in the cytosolic compartment via activation of the RhoGTPase Rac 1, which amplifies the redox function of NADPH oxidases (24, 31). Finally, the potent stress response regulator FOXO3a is a downstream target of p66 redox signals that phosphorylate and inactivate FOXO3a via an evolutionary conserved Akt/PKB-dependent pathway (4, 35, 38). Taken together, p66 controls intracellular ROS metabolism at multiple sites and is a major determinant of cell redox status.

The lack of an experimental model that faithfully recapitulates human DG (8, 10) has hindered progress in the identification of new molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. Mice heterozygous for the Akita diabetic mutation (Ins2+/C96Y) with a second null allele mutation at the B2R locus (B2R−/−) (19, 21) represent a significant advance in that hyperglycemia (HG) is more durable and sustained than streptozotocin (STZ)-induced DM (8, 10) with a disease phenotype that more closely approximates DG in humans (19, 21). These double mutant Akita (DMA) mice provide an unparalleled opportunity to explore the interaction among p66, Ins2+/C96Y, and B2R genes in the diabetic kidney. We hypothesize the redox function of p66 is indispensable for the expression of disease phenotypes induced by the Ins2 mutation alone or in combination with the B2R−/− mutation. Accordingly, Sv129/p66−/− mice (35) were backcrossed six generations to the Akita C57BL/6J background (19, 21) before mating with Akita and DMA mice to test whether loss of function mutations at the p66 locus will rescue kidneys of Akita mice from disease-causing mutations at the Ins2 and B2R loci.

Here, we report Akita mice lacking the p66 gene exhibit increased resistance to oxidative stress, marked attenuation of glomerular/tubular injury, increase number of podocytes/glomerulus, and striking reduction in urine albumin excretion (UAE). Moreover, experiments with cultured podocytes provide a rationale for the protection phenotype in kidneys of p66-null Akita mice. We find hyperglycemia (HG) activates cross talk between p66 and the redox-sensitive transcription factor p53, leading to transcription of p53 target genes, angiotensin II generation, and apoptosis. Silencing p66 by RNA interference (RNAi) inhibits all of the above. Protein levels of p53 target genes were also upregulated in kidneys of Akita mice but unchanged in p66-null Akita mice. Taken together, p66 is a potential molecular target for therapeutic intervention in DG.

METHODS

Animals.

Sv129/p66−/− mice were backcrossed six generations to the C57BL/6J background before mating with Akita (Ins2+/C96Y) and B2R−/− mice, which already have the C57BL/6J background. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Louisiana State University Health Science Center. Systolic blood pressures (SBP) were measured with the tail cuff method using CODA2 device (Kent Scientific). SBP was monitored in the morning at least three to four times per week during the last month of life (2, 6, and 12 mo of age).

Measurement of biochemical parameters.

Mice were anesthetized, and plasma samples were collected. Plasma glucose levels were determined with the glucose oxidase methods (Wako Chemical). Plasma levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARs) were determined as previously described (27). H2O2 was determined in kidney homogenates. Urinary albumin/creatinine was determined with ELISA (Albuwell-M and Creatinine-companion; Exocell).

Histological evaluation.

The kidneys were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. Paraffin sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reagent and hematoxylin or with Masson's trichrome reagent and examined under the optical microscope. Tissues were also examined under an electron microscope after fixation with 15% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde. The glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis scores were evaluated in a blind fashion as previously described (52, 43).

Immunoflourescent staining of kidney sections.

Kidneys were harvested and snap frozen according to standard protocols and sectioned at 4 μm. The sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked in PBS containing 5% BSA, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with primary antibodies. For double labeling, sections were washed three times with PBS for 5 min, and the secondary antibody was applied for 1 h. To determine the number of podocytes/glomeruli, kidneys sections were stained against the podocyte nuclear marker WT-1 and the podocyte marker synaptopodin and DAPI nuclear counterstain. Confocal images were taken with a Nikon Eclipse E400 upright fluorescence microscope equipped with an EX1 aqua camera (Qimaging), motorized Z-axis, and SlideBook5 acquisition/deconvolution software (Intelligent Imaging Innovation, Denver, CO). WT-1-positive cells were counted in 25–30 glomeruli per mouse for each of the genotypes (12).

Terminal transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling assay and immunohistochemical staining.

The percentage of apoptotic nuclei was evaluated by terminal transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL assay; Roche Diagnostics). Immunohistochemical staining was performed by standard avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method (ABC Staining System; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell culture.

Conditionally immortalized human podocytes were provided by M. A. Saleem (Children's Renal Unit, Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, University of Bristol, UK) and were cultured as previously described (17, 48).

Constructs and antibodies.

Constructs and antibodies used in this study are listed with their sources as follows: p66shRNA was from (OriGene, Rockville, MD); antibody to Src homology 2 transforming protein (ShcA) was from Cell Signaling; mouse monoclonal antibodies to phospho-p66ShcA (Ser-36) and p53 were Calbiochem; and Bax and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Transfection.

To generate p66-deficient conditionally immortalized differentiated human podocytes (CIDHP), cells were transfected with (HuSH) 29mer shRNA constructs against Src homology 2 domain containing protein 1(SHC1; Locus ID = 6464- OriGene) or HuSH shRNA cloning vector (pRS) as control using Attractene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen), according to manufacturer's protocol. The final concentration for both sets of oligonucleotides was 100 nM. Puromycin-resistant clones were collected and cultured separately. As a second approach, CIDHP were transiently transfected with position mutant-36p66ShcA (pcDNA/p66ShcA SA) expression vector, using the protocol described above. Reconstitution of wt-p66 was accomplished by transfecting CIDHP/p66shRNA with Addgene plasmid 10972: pcDNA3.1 his p66Shc (35) as described above.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting experiments were performed as previously described (32).

Detection of HG-induced oxidative stress.

Reactive oxygen intermediates were detected as previously described (4, 17, 22, 44). Culture slides were visualized with Nikon Eclipse E400 upright fluorescence microscope equipped with EX1 aqua camera (Qimaging), motorized Z-axis, and SlideBook5 acquisition/deconvolution software (Intelligent Imaging Innovation). Intracellular ROS was quantitated by SlideBook5 software. ROS signals were captured from the entire cell volume using the mask operations of SlideBook5, according to manufacturer instructions. For colocalization images to detect and quantitate ROS in mitochondria, 20 cells were imaged 3 times for empty vector (EV)-CIDHP at HG. The images were measured using a pixel correlation algorithm, with red indicating highly significant levels of colocalization (37).

Analysis of DNA fragmentation by ELISA.

Histone-associated DNA fragments were quantified by Cell Death Detection ELISA (Roche Diagnostic, Branchburg, NJ), as previously described (4, 17).

EMSA.

Single-stranded oligonucleotide probes were prepared for bax, Aogen, and the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) with biotin 3′-end DNA labeling kit, as per manufacturer's protocol (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford IL). The oligonucleotide for bax contains one perfect and three imperfect consensus motifs of p53 from the human bax gene promoter (28, 29). This sequence corresponds to −492 to −447 bp and is located 70-bp 5′ of the TATA box (GenBank U17193); Aogen probe (28, 29) corresponds to rat Aogen sequence from −599 to −575 bp, located 568-bp 5′ of the TATA box (GenBank M31673); and AT1R probe (28, 29) corresponds to rat AT1R sequence from −1,862 to 1,838 bp, located 1,813-bp 5′ of the TATA box (GenBank S66402). Nuclear extracts of CIDHP and simian virus 40-transformed T2 cells (SV-T2) cells were subject to electrophoresis on 5% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad), and signals were detected using Chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module, as per manufacturer's protocol (Pierce Biotechnology).

Angiotensin II determination by ELISA.

Angiotensin II in conditioned medium was measured by ELISA (Peninsula Laboratories, Belmont, CA) as per manufacturer's protocol.

Flow cytometery.

CIDHP maintained at serum free media containing 5 or 40 mM glucose for 48 h were analyzed for apoptosis using annexin V-PE apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) as per manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SD. To compare the effects of the Ins2 mutation, B2R null, and p66 null mutations alone and in combination, we used two-way ANOVA with a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test with GraphPad InStat software. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of wild-type and Akita mice.

Akita mice with the following genotypes (Table 1) were entered into the study protocol at 6 wk of age, when blood glucose was >350 mg/dl; mice expressing the (Ins2+/C96Y) mutation, designated simply as Akita; mice coexpressing the (Ins2+/C96Y) and (B2R−/−) mutations, designated double mutant Akita (DMA); mice coexpressing the (Ins2+/C96Y) and p66 null allele (p66−/−), designated p66KO-Akita; and mice expressing all three mutations (Ins2+/C96Y/B2R−/−/p66−/−), designated triple mutant Akita (TMA). We chose to target the p66 gene, because p66 controls the redox status of cells (3, 35, 46) and is dispensable for normal growth and development (35). Akita mice exhibit many of the untoward effects of untreated DM, including severe HG, decreased body weight, renal hypertrophy, and increased kidney weight-to-body weight ratio. Mortality was highest for Akita and DMA mice, ∼40% at 6 mo and 60% at 1 yr.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the 5 genotypes of male animals at 12 mo of age

| Genotype | WT | Akita | p66 KO AKITA | DMA | TMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of mice | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| BW, g | 40.67 ± 2.0 | 29.33 ± 1.2* | 28.67 ± 2.4* | 27.00 ± 2.2* | 30.67 ± 1.5* |

| KW, mg | 226.00 ± 17.7 | 435.50 ± 37.5* | 314.42 ± 43.2* | 380.08 ± 44.0* | 379.50 ± 39.9* |

| KW/BW, mg/g | 5.57 ± 0.6 | 14.84 ± 1.1* | 10.98 ± 1.4* | 14.12 ± 1.7* | 12.40 ± 1.4* |

| HW, mg | 178.83 ± 11.2 | 136.67 ± 11.1 | 149.33 ± 18.7 | 146.33 ± 12.5 | 143.67 ± 14.4 |

| HW/BW, mg/g | 4.40 ± 0.3 | 4.66 ± 0.3 | 5.21 ± 0.5 | 5.46 ± 0.8 | 4.71 ± 0.6 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 136.67 ± 7.2 | 744.33 ± 30.1* | 747.00 ± 33.9* | 762.17 ± 25.4* | 748.50 ± 21.2* |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 105 ± 3.0 | 108 ± 2.0 | 111 ± 4.0 | 115 ± 3.0 | 112 ± 3.0 |

Data shown are means ± SD. WT, wild type; KO, knockout; DMA, double mutant Akita; TMA, triple mutant Akita; BW, body weight; KW, kidney weight; HW, heart weight; BP, blood pressure.

P < 0.01 vs. WT.

Kidneys of Akita mice lacking p66 are rescued from disease phenotypes induced by Ins2 and B2R mutations.

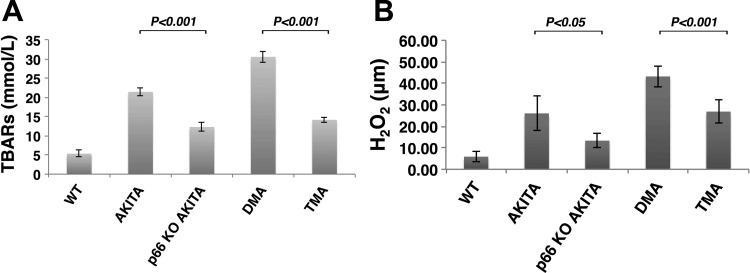

Our laboratory (4, 32) and others (3, 38, 46) have reported inhibition of p66 redox function attenuates HG-induced ROS metabolism by uncoupling ROS generation in mitochondria and cytosolic compartments. To investigate the role of p66 on systemic and renal levels of oxidative stress in Akita diabetic mice, we analyzed TBARS in plasma (Fig. 1A) and H2O2 content in kidney tissue (Fig. 1B). At comparable levels of HG, TBARS and H2O2 content was substantially reduced in p66-null Akita mice (p66KO-Akita and TMA), compared with their respective counterparts, Akita, and DMA. These results indicate p66 is necessary for HG-induced ROS metabolism.

Fig. 1.

The p66 is necessary for hyperglycemia (HG)-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism. A: plasma levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARs) in Akita diabetic mice. WT, wild type; KO, knockout. Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group. P < 0.001, Akita vs. p66KO-Akita; P < 0.001, double mutant Akita (DMA) vs. triple mutant Akita (TMA). B: H2O2 content in kidney tissue from Akita diabetic mice. Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group; P < 0.05, Akita vs. p66KO-Akita; P < 0.001, DMA vs. TMA.

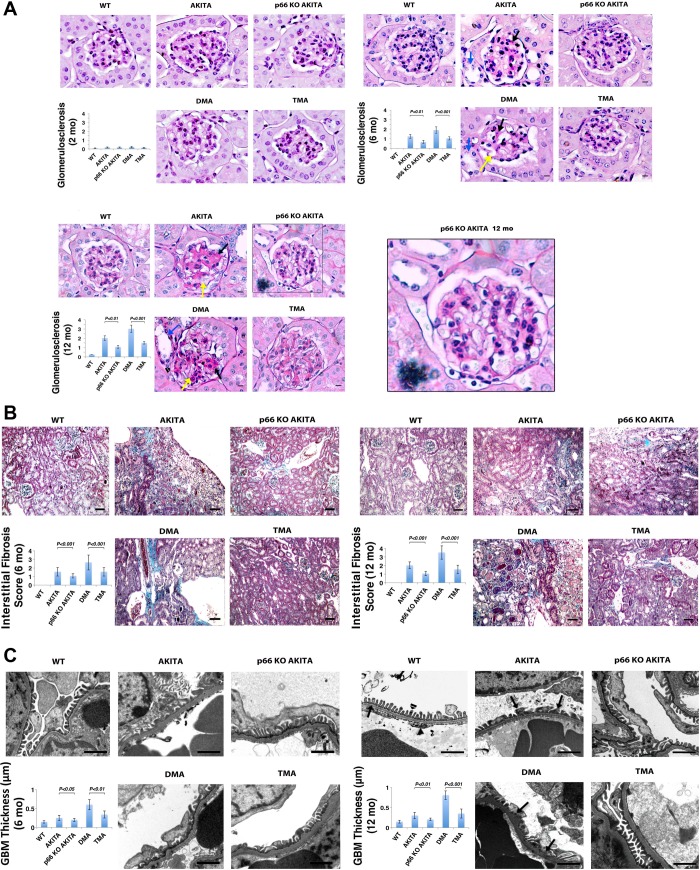

We hypothesize kidneys of p66-null Akita mice will be resistant to disease phenotypes expressed in kidneys of Akita mice. To test this hypothesis, kidney sections were evaluated in accordance with recently published guidelines (52, 43). At 2 mo of age (Fig. 2A, left), PAS-stained glomeruli from kidneys of Akita, p66KO-Akita, DMA and TMA mice show no detectable histologic changes. An identical analysis at 6 mo of age (Fig. 2A, right) shows PAS-positive extracellular matrix and mesangial expansion in glomeruli of Akita mice that are enhanced in DMA mice that show severe mesangial expansion and mesangial sclerosis. Conversely, these histologic were encountered rare in kidneys of p66KO-Akita and TMA mice. To test whether loss of function mutations at the p66 locus confer sustained reno-protection, we also examined kidneys from Akita mice at 12 mo of age. Akita and DMA mice (Fig. 2A, bottom) show nodular accumulation of PAS-positive extracellular matrix, mesangiolysis, microaneurysms, and advanced glomerulosclerosis. These lesions were barely detectable in kidneys of p66KO-Akita mice and markedly attenuated in TMA mice, indicative p66 is required for expression of disease phenotypes in kidneys of Akita mice.

Fig. 2.

p66 is necessary for expression of disease phenotype(s) in kidneys of Akita mice. A: periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of kidney sections. Ins2 mutation alone increases accumulation of PAS-positive matrix at 6 mo (right) and 12 mo of age (bottom), which is enhanced at 6 and 12 mo by the absence of the B2R. The p66-null mutation attenuates renal histological changes at corresponding intervals. Nodular PAS-positive matrix (black arrow), mesangiolysis (yellow arrow) tubular dilation (blue arrow) and microaneurysm (arrowhead). Scale bar = 10 μm. Histologic analysis of glomerulosclerosis by semiquantitative morphometric analysis (inset). Results are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group. P < 0.001, Akita vs. p66KO-Akita; P < 0.001, DMA vs. TMA. B: trichrome staining of renal cortex. DMA mice show increase interstitial fibrosis at 6 (left) and 12 mo of age (right), whereas p66-null mutation attenuates interstitial fibrosis at corresponding intervals. Scale bar = 50 μm. Histologic analysis of interstitial fibrosis assessed by semi-quantitative evaluation (inset). Results are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group. P < 0.001, Akita vs. p66 KO Akita (12 mo); P < 0.001, DMA vs. TMA. C: electron micrographs of glomeruli. Akita and DMA mice at 6 (left) and 12 (right) mo of age show thickening of glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and foot process effacement. p66KO-Akita and TMA show minimum GBM thickening and intact foot processes at corresponding interval. Scale bar = 1 μm. Inset: quantitative analysis of GBM thickness. Results are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group. P < 0.001, p66KO-Akita vs. Akita; P < 0.001, DMA vs. TMA.

Tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis are well documented in advanced DG (47). To evaluate these histologic changes, kidney sectionswere examined following trichrome staining. Akita and DMA mice at 6 mo of age (Fig. 2B, left), show dilated proximal tubules and interstitial fibrosis. At 12 mo of age (Fig. 2B, right), these histological changes are enhanced, most prominently in DMA mice and markedly attenuated in p66-null Akita mice. The interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy score (52) follows an identical order of progression for the genotypes as TBARS, H2O2, and the glomerulosclerosis score. Histologic changes in p66−/− and nondiabetic B2R−/− mice are not remarkable at this age (data not shown).

Thickening and increased permeability of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) are characteristic features of DG. To evaluate the glomerular filtration barrier images were taken by electron microscopy. At 6 (Fig. 2C, left) and 12 mo (Fig. 2C, right) of age, Akita and DMA mice show increased width of the GBM, as determined by the method of Haas (11) and extensive podocyte foot process effacement. Akita mice lacking p66 show minimal increase in GBM and intact podocyte foot processes.

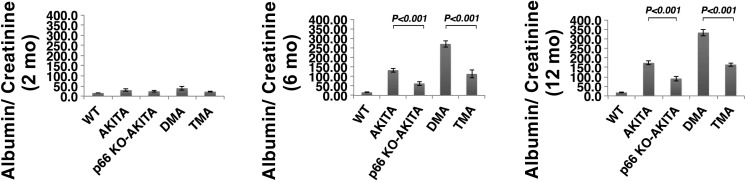

Proteinuria is a specific indicator of nephropathy in DM (1, 2, 30). At 2 mo of age (Fig. 3, left), Akita mice show no increase in the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. This parameter at 6 mo of age (Fig. 3, middle) increased by >15-fold and >30-fold × normal in Akita and DMA mice respectively. By contrast, albumin-to-creatinine ratio increased by 7-fold in p66KO-Akita and 15-fold in TMA mice. These results translate to 50% reduction in UAE for p66-null Akita mice vs. Akita and DMA mice. An identical analysis at 12 mo of age (Fig. 3, right) shows comparable increase in albumin-to-creatinine ratio in the four genotypes of Akita mice. albumin-to-creatinine ratio of p66−/− and nondiabetic B2R−/− mice at 12 mo of age was comparable to wild-type (WT) mice (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

The p66 null mutation attenuates urine albumin excretion (UAE). Akita mice at 2 mo (left), 6 mo (middle), and 12 mo of age (right). Results are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group. P < 0.001, Akita vs. p66 KO Akita; P < 0.001, DMA vs. TMA.

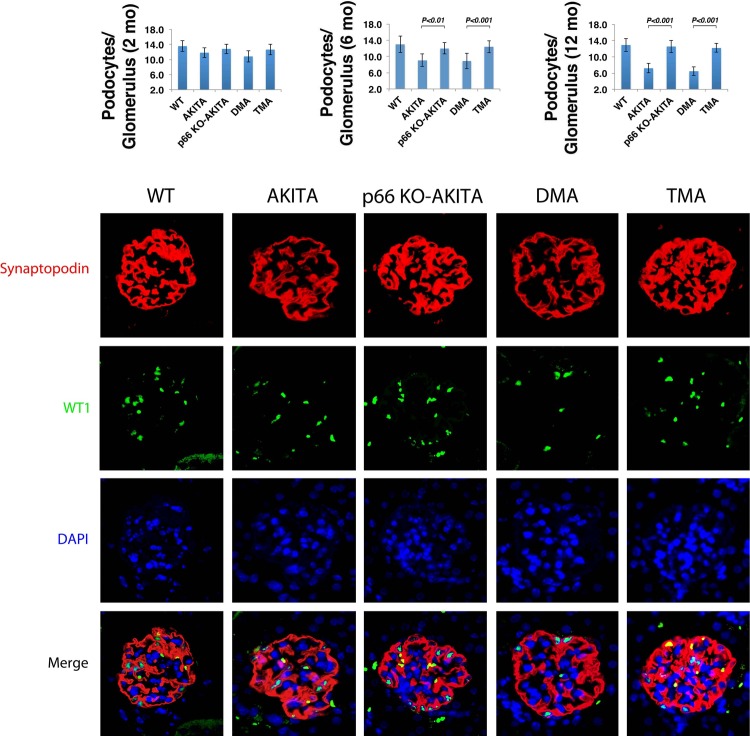

Among the various morphometric indices, podocyte number/glomerulus is the strongest predictor of disease progression in DG (42, 50). At 2 mo of age (Fig. 4, left), the number of podocytes/glomerulus in the four groups of Akita mice did not differ from WT. We find this parameter is decreased at 6 mo (Fig. 4, middle) and 12 mo (Fig. 4, right) of age in Akita and DMA mice. Conversely, at 6 and 12 mo of age, podocyte number/glomerulus in kidneys of p66KO-Akita and TMA mice is equivalent to WT and twofold greater than Akita and TMA mice. Podocyte loss is dependent on coexpression of the p66 gene and Ins2 mutation, whereas the B2R−/− mutation is dispensable for podocytopenia.

Fig. 4.

Podocyte number/glomerulus. WT-1 expressing nuclei were counted in kidneys of Akita mice at 2 mo (left), 6 mo (middle), and 12 mo of age (right). Results are presented as means ± SD; n = 5 in each group; 30 glomeruli from each mouse were analyzed. P 0.01, p66 KO Akita vs. Akita (6 mo); P 0.001, p66 KO Akita vs. Akita (12 mo), DMA vs. TMA (6 and 12 mo). Confocal images of glomeruli showing podocyte specific marker synaptopodin (red); podocyte nuclear marker WT-1 (green); nuclear counterstain DAPI (blue) in kidneys sections at 12 mo of age.

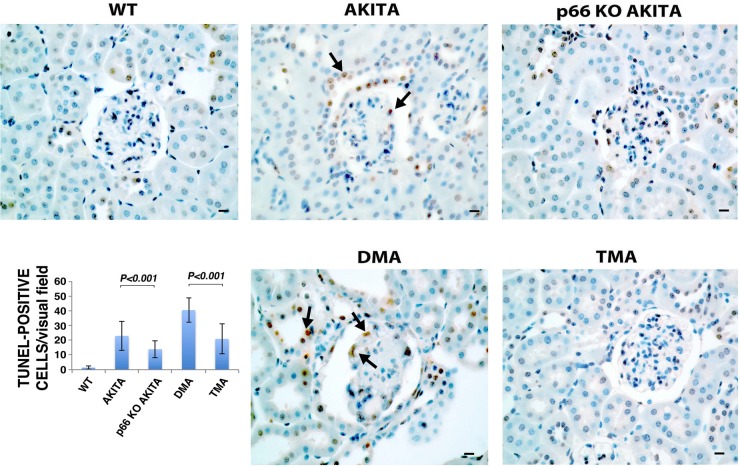

Apoptosis contributes to the development and progression of DG (23, 51). The DNA double helix is a target for ROS-dependent signals (33, 39). To evaluate apoptosis in Akita mice, TUNEL assay was performed on kidney sections (Fig. 5). TUNEL-positive nuclei were only rarely seen in kidney sections from WT mice, whereas this parameter was clearly increased in sections from Akita and DMA mice. By contrast, TUNEL-positive nuclei were substantially reduced in kidney sections from p66KO-Akita and TMA mice. Taken together, the p66 null mutation increases resistance of resident glomerular and tubular cells to apoptotic stimuli.

Fig. 5.

Detection of apoptosis by terminal transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. Representative images of TUNEL staining in kidney sections of WT and Akita mice. Arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. Scale bar = 10 μm. Quantitative analysis of TUNEL-positive nuclei. Results shown are presented as means ± SD; n = 5. P < 0.01, Akita vs. p66KO-Akita; P < 0.01, DMA vs. TMA.

Inactivation of p66 inhibits HG-induction of p53 target genes in podocytes and kidneys of Akita mice.

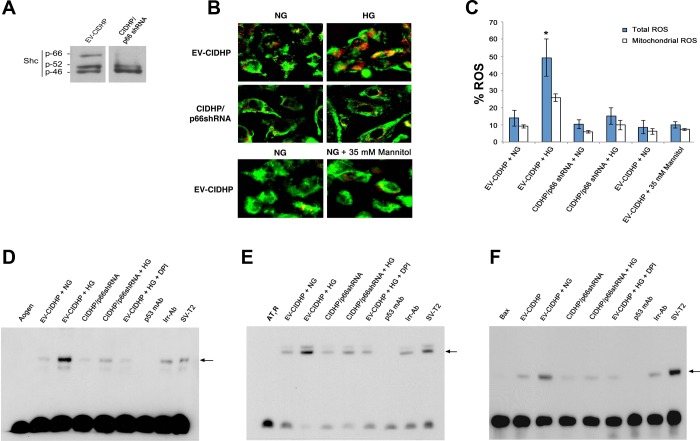

To elucidate the mechanism(s) by which inactivating mutations at the p66 locus confer a protection phenotype in kidneys of Akita mice, we turned to podocytes in culture. The redox-sensitive transcription factor p53 controls the expression profile of Aogen, AT1R, and the proapoptosis protein bax (28, 29). We hypothesize hyperglycemia activates cross talk between p66 and p53, leading to transcription of p53 target genes in kidneys of Akita mice. To test this hypothesis, we used RNAi strategy in CIDHP to knockdown p66 protein levels with an isoform-specific p66shRNA expression vector (Fig. 6A). To evaluate intracellular ROS, cells were loaded with the redox-sensitive fluoroprobes Redox Sensor Red CC-1 and the mitochondrial specific dye MitoTracker Green FM (4, 17). In preliminary studies, the signal for HG-induced intracellular ROS was detected at 16 and 24 h and was most robust at 48 h. Accordingly, here and in all protocols that follow, CIDHP were maintained for 48 h in serum free media containing 5 mM glucose [normal glucose (NG)] or 40 mM glucose (HG). As shown in Fig. 6B, top, EV-CIDHP at HG exhibit bright yellow fluorescence due to the localization of Red CC-1 and MitoTracker green FM in mitochondria, whereas red/orange fluorescence indicates oxidation of Red CC-1 in the cytoplasmic compartment. Consistent with the reduced levels of H2O2 content in kidneys of p66 null Akita mice, CIDHP/p66shRNA maintained at HG (Fig. 6B, middle) show quenching of the ROS signal. As control of osmolarity, EV-CIDHP were maintained under osmolar equivalent conditions (5 mM glucose + 35 mM mannitol). ROS were barely detectable, indicative HG-induced ROS was independent of osmolar forces. Figure 6C shows quantification of ROS.

Fig. 6.

The p66 redox signals activate p53 DNA binding. A: immunoblot analysis of ShcA isoforms in conditionally immortalized differentiated human podocytes (CIDHP) stably transfected with p66shRNA. B: CIDHP/p66shRNA shows inhibition of HG-induced ROS metabolism. C: quantitative of ROS in empty vector (EV)-CIDHP and CIDHP/p66 shRNA cells. *P < 0.01. EMSA showing p53 binding to the consensus sequence at the promoter of Aogen (D), angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R; E), and bax (F). Nuclear extracts from SV-T2 cells overexpressing p53 were used as a positive control. Arrow indicates position of p53 specific band. Aogen indicates Aogen probe; AT1R indicates AT1R probe; Bax indicates bax probe; each case in the absence of nuclear extracts. Specificity was established by documenting incubation with monoclonal p53 antibody (p53 mAb) inhibits the p53 band complex whereas irrelevant antibody (Irr-p53) was without effect. EV-CIDHP at HG show increase in the intensity of p53 specific band complex for Aogen, AT1R, and bax. EV-CIDHP maintained at HG, in the presence of free radical scavenger DPI, show no increase in the intensity of the p53 band complex for Aogen, AT1R, and bax. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments.

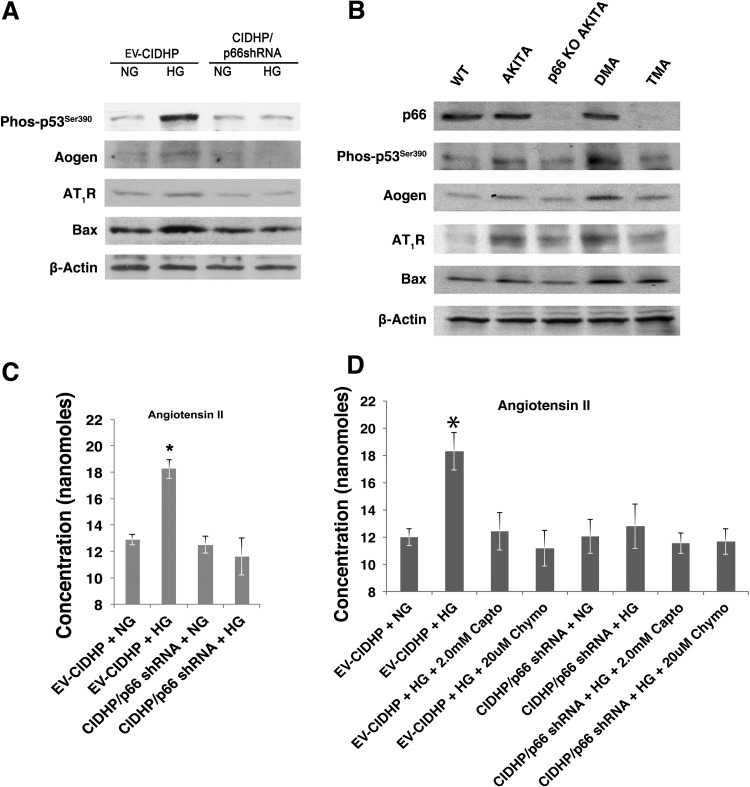

To test whether p66 redox signals are required for transactivation of p53 target genes, nuclear extracts were prepared from EV-CIDHP and CIDHP/p66shRNA and subjected to EMSA. The promoters of Aogen and AT1R contain 7 out of 10 matches with the consensus sequence of p53 (28, 29). The bax promoter contains one perfect p53 binding site and three imperfect binding sites (28, 29). As shown (Fig. 6, D–F), one complex with shifted gel mobility was found in nuclear extracts from EV-CIDHP and CIDHP expressing p66shRNA, the intensity of which increased for Aogen, AT1R, and bax, in the extracts from EV-CIDHP maintained at HG. These results show in podocytes maintained at HG that p66 is required for transcriptional activation of p53 target genes. In agreement with EMSA results, immunoblot analysis detected increased protein levels of Aogen, AT1R, and bax in lysates from EV-CIDHP (Fig. 7A) at HG and kidney sections from Akita and DMA mice (Fig. 7B). Levels of phos-p53Ser90 posttranslational modification associated with transcriptional activation of p53 (14) were also upregulated in EV-CIDHP and kidneys of Akita and DMA mice.

Fig. 7.

The p66 is necessary for expression of p53 target genes. A: effect of p66-shRNA on expression of p53 target genes. Representative immunoblot analysis of Aogen, AT1R, and bax protein levels. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. B: effect of p66-null mutation on renal expression of p53 and p53 target genes. Represenative immunoblot analysis of kidney from WT and Akita mice at 12 mo of age. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. C: effect of p66-shRNA on synthesis and release of angiotensin II. D: effect of ACE and non-ACE inhibitors on HG induced angiotensin II generation. Data are presented as means ± SD and represent 4 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.01.

To determine whether these molecular events translate to increase angiotensin II generation at the cellular level, we analyzed the conditioned media from cells maintained at NG and HG (Fig. 7C). EV-CIDHP maintained at HG show increase angiotensin II content in conditioned media, whereas CIDHP/p66shRNA show no change in ambient angiotensin II levels. To evaluate the source of angiotensin II, captopril (ACE-inhibitor) and chymostatin (non-ACE) were added to culture media (5). In separate analyses (Fig. 7 D), captopril and chymostatin reduced angiotensin II content by 50%, indicative angiotensin II was generated by both ACE and non-ACE pathways. The addition of captopril or chymostatin to culture media of CIDHP/p66shRNA at HG did not result in a further decrease in ambient angiotensin II levels. These results demonstrate knock down of p66 expression inhibits angiotensin generation by ACE and non-ACE pathways. Taken together, HG activates cross talk between p66 and p53, which in turn increases availability of the renin substrate Aogen, leading to the local generation of angiotensin II.

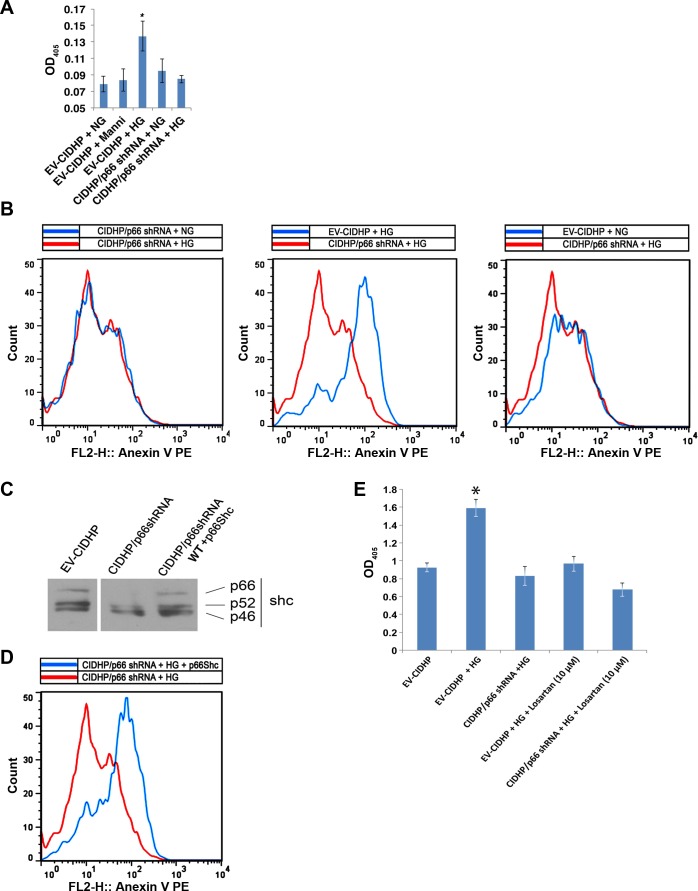

P66 and angiotensin II are necessary for HG-induced apoptosis.

p66 converts oxidative stress in cells into apoptosis (3, 4, 17). Accordingly, we evaluated apoptosis in our system by cell death ELISA and annexin V binding. The apoptosis signals by cell death ELISA increased 1.5-fold in EV-CIDHP maintained at HG (Fig. 8A), whereas CIDHP/p66shRNA show no change from NG. Annexin V assay confirmed these results (Fig. 8B). To test whether p66 is required for HG-induced apoptosis, wt-p66ShcA was reexpressed in CIDHP/p66shRNA (Fig. 8C). Reconstitution of p66 restored sensitivity to the HG apoptosis signal (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

The p66 and angiotensin II are necessary for HG-induced apoptosis. A: histone associated DNA fragments were quantified and presented as optical density at 405 nm (OD405). Results are presented as means ± SD and represent 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.01. B: Representative flow cytometric analysis showing detection of apoptosis by annexin V binding. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. C: representative immunoblot analysis showing expression of WT p66ShcA in CIDHP/p66shRNA. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. D: flow cytometric analysis of annexin V binding with reconstituted CIDHP/p66shRNA. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. E: losartan inhibits HG-induced apoptosis. Results are presented as means ± SD and represent 3–4 independent experiments. *P < 0.01.

Podocytes have also been reported to enter the apoptosis program following challenge with exogenous angiotensin II (18). We next asked whether increased synthesis and release of angiotensin II by podocytes activates an autocrine signaling module to trigger apoptosis. In a manner identical to p66shRNA, we find the addition of the AT1R antagonist losartan to culture media of EV-CIDHP inhibits the HG apoptosis signal (Fig. 8E). These results suggest targeting p66 by RNAi inhibits the HG apoptosis signal by limiting the availability of the renin substrate Aogen, which in turn attenuates the local generation of angiotensin II. Taken together, in podocytes maintained at high glucose p66 transmits the death signal via AT1R-dependent mechanism.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report demonstrating null mutations in the Akita genome, positioned at the p66 and B2R loci, induce divergent phenotypes in the diabetic kidney. We demonstrate p66 and B2R mutations interact independently and in combination with the Ins2 mutation to orchestrate the phenotype expressed in kidneys of Akita mice. The detrimental phenotype of the B2R−/− mutation has been reported (19, 21) and is perhaps not unexpected, since activation of B2R promotes nitric oxide production, a potent vasodilator that also functions as a free radical scavenger (20). Kakoki et al. (19) has reported knockout of the bradykinin 1 receptor (B1R) enhances the disease phenotype expressed in kidneys of Akita mice lacking the B2R. We find p66 is necessary for expression of disease phenotypes in kidneys of Akita mice. Conversely, p66KO-Akita and TMA mice show marked improvement in multiple outcomes. We speculate that p66 is a maladaptive stress gene that has escaped forces of natural selection, whose function in the diabetic kidney is to promote disease progression.

The antiproteinuric effect of the p66 null mutation is consistent with the observation podocyte number and foot processes are conserved in Akita mice lacking p66 sufficient for kidney podocyte loss, whereas the B2R −/− mutation is dispensable. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating inactivating mutations at the p66 locus not only confer a survival advantage to the terminally differentiated podocyte but also prevents foot process effacement to retain the stationary podocyte phenotype. It seems reasonable to infer these critical determinants of glomerular barrier function (36, 7, 49, 55), contribute to the reduced levels of UAE. Notably, we find expression of Ins2 mutation and p66 gene is sufficient for kidney podocyte loss, whereas the B2R −/− mutation is dispensable. Our work builds upon and adds to a previous report in p66−/− mice with STZ-DM (34), linking p66 and ROS to the pathogenesis of DG. A decided strength of the present study is the Akita mouse model that is genetically engineered to express a disease phenotype that approximates human DG (19, 21), thereby discounting concerns about the relevance of STZ-DM (10) and whether it is an acceptable experimental model for DG (8, 10, 20).

The experiments with cultured podocytes reveal previously unrecognized cross talk between p66 and the redox-sensitive transcription factor p53. We find upregulation of the p53 target genes Aogen and AT1R coupled with increased synthesis and release of angiotensin II. Aogen is the rate-limiting step in angiotensin II generation (9). Angiotensin II levels released from podocytes were sufficient to activate AT1R-dependent apoptosis, indicative of a functional autocrine signaling module (16). We have not determined whether the regulatory events demonstrated here in cultured podocytes translate to the in vivo setting. It must also be acknowledged previous work with mouse embryonic fibroblasts and endothelial cells (25, 53) has demonstrated p66 also functions as a downstream effector of p53. Taken together, regulatory mechanism(s) may exist to integrate p66 and p53 signaling pathways, which share overlapping biological functions, including ROS metabolism, cell cycle arrest, aging, and apoptosis (35, 53).

The present study has certain limitations including the necessity to maintain cells under serum free media to eliminate the confounding effects of serum and contained growth factors on signaling pathways linked to cell survival and oxidant reference (38). Moreover, we must acknowledge the limitations of short-term in vitro cell culture systems in simulating a complex metabolic disorder such as DM. Although hypertension is not part of the disease phenotype reported in Akita mice, the limited number of observations reported here and the limitations of tail cuff blood pressure measurements must be acknowledged. The focus of the present study was the interaction of p66, Ins2, and B2R−/− mutation on disease phenotype(s) expressed in kidneys of Akita mice. It remains to be determined whether more sophisticated analysis by telemetry, in larger samplings of Akita mice, will show an interaction of these genes in hypertension. Finally in future investigations it will also be important to correlate advanced histologic changes shown here, with reliable measurements of glomerular filtration rate (45).

Taking these limitations into account, our findings construct a new paradigm for the pathobiology of DG, in which p66 controls systemic and renal levels of oxidative stress, while orchestrating the expression of stress gene programs that lead to the remodeling of the diabetic kidney. To the best of our knowledge, there are no comparable data in a mouse model of diabetic nephropathy. We believe our work will offer an exciting avenue for therapeutic intervention in DG and other glomerular disorders, where ROS have been implicated in metabolic, toxic, and inflammatory insults (13, 26, 32).

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 1RO1-DK-073793 and 3RO1-DK-073793–01A2S1 (to L. G. Meggs), 5RO1-DK-083931 (to P. C. Singhal), and 2RO-1CA-095518 (to K. Reiss).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: LGM concieved and directed the project. H.V., P.C.S., A.M., K.R., and L.G.M. conception and design of research; H.V., A.M., M.H., C.K., S.S., A.W., and H.-S.K. performed experiments; H.V., P.C.S., A.M., M.H., S.S., l.D., F.P., M.K., K.R., and L.G.M. analyzed data; H.V., P.C.S., A.M., P.W.M., M.A.S., C.K., S.S., l.D., F.P., m.G., P.G.P., O.S., M.K., K.R., and L.G.M. interpreted results of experiments; H.V. prepared figures; H.V., K.R., and L.G.M. drafted manuscript; H.V. and L.G.M. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brenner BM. Remission of renal disease: recounting the challenge, acquiring the goal. J Clin Invest 110: 1753–1758, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Camici GG, Schiavoni M, Francia P, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, Hersberger M, Tanner FC, Pelicci P, Volpe M, Anversa P, Luscher TF, Cosentino F. Genetic deletion of p66(Shc) adaptor protein prevents hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 5217–5222, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chintapalli J, Yang S, Opawumi D, Goyal SR, Shamsuddin N, Malhotra A, Reiss K, Meggs LG. Inhibition of wild-type p66ShcA in mesangial cells prevents glycooxidant-dependent FOXO3a regulation and promotes the survival phenotype. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F523–F530, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durvasula RV, Shankland SJ. Activation of a local renin angiotensin system in podocytes by glucose. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F830–F839, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eid AA, Gorin Y, Fagg BM, Maalouf R, Barnes JL, Block K, Abboud HE. Mechanisms of podocyte injury in diabetes: role of cytochrome P450 and NADPH oxidases. Diabetes 58: 1201–1211, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Faul C, Donnelly M, Merscher-Gomez S, Chang YH, Franz S, Delfgaauw J, Chang JM, Choi HY, Campbell KN, Kim K, Reiser J, Mundel P. The actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes is a direct target of the antiproteinuric effect of cyclosporine A. Nat Med 14: 931–938, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fogo AB. The targeted podocyte. J Clin Invest 121: 2142–2145, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gould AB, Green D. Kinetics of the human renin and human substrate reaction. Cardiovasc Res 5: 86–89, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gurley SB, Clare SE, Snow KP, Hu A, Meyer TW, Coffman TM. Impact of genetic background on nephropathy in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F214–F222, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haas M. Alport syndrome and thin glomerular basement membrane nephropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 133: 224–232, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartleben B, Godel M, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Liu S, Ulrich T, Kobler S, Wiech T, Grahammer F, Arnold SJ, Lindenmeyer MT, Cohen CD, Pavenstadt H, Kerjaschki D, Mizushima N, Shaw AS, Walz G, Huber TB. Autophagy influences glomerular disease susceptibility and maintains podocyte homeostasis in aging mice. J Clin Invest 120: 1084–1096, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hasty P, Campisi J, Hoeijmakers J, van Steeg H, Vijg J. Aging and genome maintenance: lessons from the mouse? Science 299: 1355–1359, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hecker D, Page G, Lohrum M, Weiland S, Scheidtmann KH. Complex regulation of the DNA-binding activity of p53 by phosphorylation: differential effects of individual phosphorylation sites on the interaction with different binding motifs. Oncogene 12: 953–961, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang W, Gallois Y, Bouby N, Bruneval P, Heudes D, Belair MF, Krege JH, Meneton P, Marre M, Smithies O, Alhenc-Gelas F. Genetically increased angiotensin I-converting enzyme level and renal complications in the diabetic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13330–13334, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hunyady L, Catt KJ. Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol 20: 953–970, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Husain M, Meggs LG, Vashistha H, Simoes S, Griffiths KO, Kumar D, Mikulak J, Mathieson PW, Saleem MA, Del Valle L, Pina-Oviedo S, Wang JY, Seshan SV, Malhotra A, Reiss K, Singhal PC. Inhibition of p66ShcA longevity gene rescues podocytes from HIV-1-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 284: 16648–16658, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jia J, Ding G, Zhu J, Chen C, Liang W, Franki N, Singhal PC. Angiotensin II infusion induces nephrin expression changes and podocyte apoptosis. Am J Nephrol 28: 500–507, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kakoki M, Sullivan KA, Backus C, Hayes JM, Oh SS, Hua K, Gasim AM, Tomita H, Grant R, Nossov SB, Kim HS, Jennette JC, Feldman EL, Smithies O. Lack of both bradykinin B1 and B2 receptors enhances nephropathy, neuropathy, and bone mineral loss in Akita diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10190–10195, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kakoki M, Kizer CM, Yi X, Takahashi N, Kim HS, Bagnell CR, Edgell CJ, Maeda N, Jennette JC, Smithies O. Senescence-associated phenotypes in Akita diabetic mice are enhanced by absence of bradykinin B2 receptors. J Clin Invest 116: 1302–1309, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kakoki M, Takahashi N, Jennette JC, Smithies O. Diabetic nephropathy is markedly enhanced in mice lacking the bradykinin B2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13302–13305, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kang BP, Urbonas A, Baddoo A, Baskin S, Malhotra A, Meggs LG. IGF1 inhibits the mitochondrial apoptosis program in mesangial cells exposed to high glucose. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F1013–F1024, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanwar YS, Wada J, Sun L, Xie P, Wallner EI, Chen S, Chugh S, Danesh FR. Diabetic nephropathy: mechanisms of renal disease progression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 4–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khanday FA, Yamamori T, Mattagajasingh I, Zhang Z, Bugayenko A, Naqvi A, Santhanam L, Nabi N, Kasuno K, Day BW, Irani K. Rac1 leads to phosphorylation-dependent increase in stability of the p66shc adaptor protein: role in Rac1-induced oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell 17: 122–129, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim CS, Jung SB, Naqvi A, Hoffman TA, DeRicco J, Yamamori T, Cole MP, Jeon BH, Irani K. p53 impairs endothelium-dependent vasomotor function through transcriptional upregulation of p66shc. Circ Res 103: 1441–1450, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kojima K, Davidovits A, Poczewski H, Langer B, Uchida S, Nagy-Bojarski K, Hovorka A, Sedivy R, Kerjaschki D. Podocyte flattening, and disorder of glomerular basement membrane are associated with splitting of dystroglycan-matrix interaction. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2079–2089, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lapenna D, Ciofani G, Pierdomenico SD, Giamberardino MA, Cuccurullo F. Reaction conditions affecting the relationship between thiobarbituric acid reactivity, and lipid peroxides in human plasma. Free Radic Biol Med 31: 331–335, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leri A, Liu Y, Wang X, Kajstura J, Malhotra A, Meggs LG, Anversa P. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-1 attenuates the myocyte renin-angiotensin system in transgenic mice. Circ Res 84: 752–762, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leri A, Claudio PP, Li Q, Wang X, Reiss K, Wang S, Malhotra A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Stretch-mediated release of angiotensin II induces myocyte apoptosis by activating p53 that enhances the local renin-angiotensin system, and decreases the Bcl-2-to-Bax protein ratio in the cell. J Clin Invest 101: 1326–1342, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 329: 1456–1462, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li J, Zhu H, Shen E, Wan L, Arnold JM, Peng T. Deficiency of rac1 blocks NADPH oxidase activation, inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress, and reduces myocardial remodeling in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 59: 2033–2042, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malhotra A, Vashistha H, Yadav VS, Dube MG, Kalra SP, Abdellatif M, Meggs LG. Inhibition of p66ShcA redox activity in cardiac muscle cells attenuates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H380–H388, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marshall CB, Pippin JW, Krofft RD, Shankland SJ. Puromycin aminonucleoside induces oxidant-dependent DNA damage in podocytes in vitro and in vivo. Kidney Int 70: 1962–1973, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Menini S, Amadio L, Oddi G, Ricci C, Pesce C, Pugliese F, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci P, Iacobini C, Pugliese G. Deletion of p66Shc longevity gene protects against experimental diabetic glomerulopathy by preventing diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Diabetes 55: 1642–1650, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature 402: 309–313, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mundel P, Reiser J. Proteinuria: an enzymatic disease of the podocyte? Kidney Int 77: 571–580, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Naresh A, Long W, Vidal GA, Wimley WC, Marrero L, Sartor CI, Tovey S, Cooke TG, Bartlett JM, Jones FE. The ERBB4/HER4 intracellular domain is a BH3-only 4ICD protein promoting apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 66: 6412–6420, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science 295: 2450–2452, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Apoptosis: life and death decisions. Science 299: 214–215, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, Brownlee M. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature 404: 787–790, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Moroni M, Contursi C, Raker VA, Piccini D, Martin-Padura I, Pelliccia G, Trinei M, Bono M, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Ferrini M, Mannucci R, Nicoletti I, Lanfrancone L, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG. The life span determinant p66Shc localizes to mitochondria where it associates with mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 and regulates trans-membrane potential. J Biol Chem 279: 25689–25695, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pagtalunan ME, Miller PL, Jumping-Eagle S, Nelson RG, Myers BD, Rennke HG, Coplon NS, Sun L, Meyer TW. Podocyte loss and progressive glomerular injury in type II diabetes. J Clin Invest 99: 342–348, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perrin NE, Torbjornsdotter TB, Jaremko GA, Berg UB. The course of diabetic glomerulopathy in patients with type I diabetes: a 6-year follow-up with serial biopsies. Kidney Int 69: 699–705, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Contursi C, Minucci S, Mantovani F, Wieckowski MR, Del Sal G, Pelicci PG, Rizzuto R. Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science 315: 659–663, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qi Z, Whitt I, Mehta A, Jin J, Zhao M, Harris RC, Fogo AB, Breyer MD. Serial determination of glomerular filtration rate in conscious mice using FITC-inulin clearance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F590–F596, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rota M, LeCapitaine N, Hosoda T, Boni A, De Angelis A, Padin-Iruegas ME, Esposito G, Vitale S, Urbanek K, Casarsa C, Giorgio M, Luscher TF, Pelicci PG, Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J. Diabetes promotes cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure, which are prevented by deletion of the p66shc gene. Circ Res 99: 42–52, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ruster C, Wolf G. Angiotensin II as a morphogenic cytokine stimulating renal fibrogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1189–1199, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saleem MA, O′Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P. Aconditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin, and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 630–638, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sever S, Altintas MM, Nankoe SR, Moller CC, Ko D, Wei C, Henderson J, del Re EC, Hsing L, Erickson A, Cohen CD, Kretzler M, Kerjaschki D, Rudensky A, Nikolic B, Reiser J. Proteolytic processing of dynamin by cytoplasmic cathepsin L is a mechanism for proteinuric kidney disease. J Clin Invest 117: 2095–2104, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shankland SJ. The podocyte's response to injury: role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 69: 2131–2147, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, Bottinger EP. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 55: 225–233, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tervaert TW, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Haas M, de Heer E, Joh K, Noel LH, Radhakrishnan J, Seshan SV, Bajema IM, Bruijn JA. Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 556–563, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Trinei M, Giorgio M, Cicalese A, Barozzi S, Ventura A, Migliaccio E, Milia E, Padura IM, Raker VA, Maccarana M, Petronilli V, Minucci S, Bernardi P, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG A. p53-p66Shc signalling pathway controls intracellular redox status, levels of oxidation-damaged DNA and oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 21: 3872–3878, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. US Renal Data System Annual Data Report: Atlas of End Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wei C, Moller CC, Altintas MM, Li J, Schwarz K, Zacchigna S, Xie L, Henger A, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Cowan P, Kretzler M, Parrilla R, Bendayan M, Gupta V, Nikolic B, Kalluri R, Carmeliet P, Mundel P, Reiser J. Modification of kidney barrier function by the urokinase receptor. Nat Med 14: 55–63, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]