Abstract

Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) are more depolarized and display higher Ca2+ levels in pulmonary hypertension (PH). Whether the functional properties and expression of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (ClCa), an important excitatory mechanism in PASMCs, are altered in PH is unknown. The potential role of ClCa channels in PH was investigated using the monocrotaline (MCT)-induced PH model in the rat. Three weeks postinjection with a single dose of MCT (50 mg/kg ip), the animals developed right ventricular hypertrophy (heart weight measurements) and changes in pulmonary arterial flow (pulse-waved Doppler imaging) that were consistent with increased pulmonary arterial pressure and PH. Whole cell patch experiments revealed an increase in niflumic acid (NFA)-sensitive Ca2+-activated Cl− current [ICl(Ca)] density in PASMCs from large conduit and small intralobar pulmonary arteries of MCT-treated rats vs. aged-matched saline-injected controls. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis revealed that the alterations in ICl(Ca) were accompanied by parallel changes in the expression of TMEM16A, a gene recently shown to encode for ClCa channels. The contraction to serotonin of conduit and intralobar pulmonary arteries from MCT-treated rats exhibited greater sensitivity to nifedipine (1 μM), an l-type Ca2+ channel blocker, and NFA (30 or 100 μM, with or without 10 μM indomethacin to inhibit cyclooxygenases) or T16AInh-A01 (10 μM), TMEM16A/ClCa channel inhibitors, than that of control animals. In conclusion, augmented ClCa/TMEM16A channel activity is a major contributor to the changes in electromechanical coupling of PA in this model of PH. TMEM16A-encoded channels may therefore represent a novel therapeutic target in this disease.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial tone, TMEM16A, anoctamin-1, Ca2+-activated Cl− channel, patch-clamp technique

pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined as a sustained high blood pressure (>25 mmHg at rest and >30 mmHg during exercise) in the main pulmonary artery (PA) that ultimately leads to failure of the right hand side of the heart and death (4). Characteristic pathophysiological manifestations of PH are enhanced vasoconstriction, thickening of the arterial muscle wall, and a propensity for thrombosis, as a result of changes in all layers of the blood vessel, but little is known about the molecular mechanisms that drive these pathological responses. It is well established that pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) from animal models of PH and human PH patients are more depolarized and exhibit a higher intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) than cells from healthy individuals and several ionic conductances are altered in PASMCs from animal models of PH and PH patients (4, 13, 29, 43, 68, 70). Except for one recent study carried out using the chronic hypoxic model of PH in the rat (58), there is little information regarding the potential role of Ca2+-activated Cl− chloride channels (ClCa) in PH. ClCa are small conductance (∼1–3 pS) anion permeable channels evoked by a rise in [Ca2+]I that generate sufficient depolarization to increase Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels markedly and underpin excitatory responses to vasoconstrictors (41). Pulmonary arterial smooth muscles exhibit pronounced ClCa channel activities that undergo considerable regulation (41) and are now believed to be encoded by the gene TMEM16A. Several members of this gene family were recently shown by three independent groups to be translated into a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel bearing similar biophysical properties to native Ca2+-activated Cl− currents [ICl(Ca); Refs. 11, 55, 66]. TMEM16A is robustly expressed at the mRNA and protein levels in vascular smooth muscle cells (14), and its knockdown by small interfering (si)RNA resulted in a markedly reduced ClCa conductance in rat pulmonary (44) and cerebral (60, 62) artery myocytes. The present study aimed at characterizing the biophysical properties and functional role of ClCa channels in smooth muscle of conduit and intralobar pulmonary arteries of rats treated with monocrotaline (MCT) to induce pulmonary hypertension and to ascertain the relative abundance of TMEM16A in healthy and diseased arteries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

All procedures pertaining to housing conditions and animal handling were approved by the University of Nevada Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 00365) in accordance with then National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996). Male Wistar rats weighing 200–350 g were used in the present study. Animals were assigned into one of two groups: MCT-induced pulmonary hypertensive or age-matched saline-injected controls.

Animal model of pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary hypertension was induced with a single intraperitoneal injection of MCT (50 mg/kg; 1 ml/100 g body wt) freshly dissolved in 1 M HCl and diluted appropriately with PBS (pH 7.0, 0.1 M NaOH; Ref. 13). Age-matched controls were injected with an equal volume of buffer. The rats were housed two per cage (one control, one MCT-treated), allowed free access to food and water, and kept on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle for 3-wk postinjection. The rats were euthanized by an overdose of CO2, followed by removal of the heart and lungs.

Assessment of right ventricular hypertrophy.

Right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy is considered to be an indirect measure of PH (6), as increased pressure within the PA leads to thickening of the RV wall due to increased workload. The heart was dissected such that the RV was separated from the left ventricle (LV) and septum (S). Both portions of the heart were weighed and expressed as a ratio (RV/LV + S).

Doppler pulsed-wave imaging.

Transthoracic Doppler imaging was performed in some animals using a GE Vivid 7.0 Pro Color Ultrasound system (PGS Medical, Indianapolis, IN) with a 13-MHz linear transducer (i13L) and EchoPAC software (GE Healthcare). In some experiments, the Vevo 2100 Ultrasound System (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) was used instead with a 16-MHz linear transducer. All measurements represent the means of three or four cardiac cycles. Pulse-wave Doppler of pulmonary outflow was recorded in the parasternal view at the level of the aortic valve. The sample volume was placed proximal (5 mm) to the pulmonary valve leaflets and aligned to maximize laminar flow. In addition to characterization of the pulmonary outflow Doppler envelope, the pulmonary arterial acceleration time (PAAT), velocity time integral (VTI), and ejection time were measured. The VTI was obtained by tracing the outer edge of the pulmonary outflow Doppler profile. Acceleration time was measured from the time of onset of systolic flow to peak pulmonary outflow velocity. Ejection time was measured as the time from onset to completion of systolic pulmonary flow. The tricuspid valve was interrogated for the presence of tricuspid regurgitation with color and continuous-wave Doppler in the apical four-chamber view so that the tricuspid and mitral valves could be clearly visualized. If tricuspid regurgitation was observed, the transducer was aligned to achieve the maximal peak velocity. Doppler tracings were recorded at a sweep speed of 200 mm/s.

Dissection of pulmonary arteries.

Upon removal, the heart and lungs were immediately immersed in a low Ca2+ (10 μM; ∼4°C) physiological salt solution of the following composition (in mM): 120 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.2 KCl, 0.6 KH2PO43−, 1.2 MgCl2, 11.1 glucose, 24.98 taurine, 0.00973 adenosine, and 0.01 CaCl2. Second branch (conduit) and third order intralobar (resistance) pulmonary arteries were carefully dissected away from the heart and lungs and cleaned of any fat and connective tissue. For conduit PA, the endothelium was removed by passing a continuous stream of air bubbles through the lumen of the blood vessel via a syringe whereas rubbing the lumen with a small tungsten wire removed the endothelium of smaller resistance vessels.

Isolation of PASMCs.

Single rat PASMCs were isolated using a similar method to that previously described by our group for rabbit myocytes (3, 5, 24, 25, 63). In brief, cells were prepared from either second or third (intralobar) pulmonary arterial branches excised from the animal as described above. The PA tissues were cut into small strips (∼2 × 2 mm) and incubated overnight (∼16 h) at 4°C in a low Ca2+ physiological salt solution (see composition above) containing 10 or 50 μM CaCl2 and ∼0.2–0.5 mg/ml papain, 0.15 mg/ml dithiothreitol, and 2 mg/ml BSA. The next morning, the partially digested tissue pieces were rinsed three times in low Ca2+ PSS and incubated in the same solution for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were released by gentle agitation with a wide bore Pasteur pipette and then stored at 4°C until used (within 10 h following dispersion).

Whole cell patch-clamp experiments.

The whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was used to measure macroscopic calcium-activated chloride currents [ICl(Ca)] from freshly dispersed rat PASMCs (described above), according to methods previously described for rabbit PA (3, 5, 24, 25, 63). All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C). Cells were allowed to settle for ∼10 min before being perfused with the following external solution (in mM): 126 NaCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 20.0 glucose, 10 HEPES, 10 TEA-Cl, and 1.8 CaCl2 (pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH). The pipette solution used to record ICl(Ca) had the following composition (in mM): 10 BAPTA, 5 HEPES, 20 TEA-Cl, 106 CsCl, 0.2 GTP, and 3 Na2ATP. Free Mg2+ concentration was set to 0.5 mM and free [Ca2+] was set to 500 nM as calculated by the MaxChelator software (http://www.stanford.edu/∼cpatton/downloads.htm). The above solutions were designed to minimize the contamination of ICl(Ca) by other types of current. ICl(Ca) was evoked immediately upon rupture of the cell membrane, and the voltage-dependent properties were monitored every 10 s by stepping from a holding potential of −50 to +90 mV for 1 s, followed by repolarization to −80 mV for 1 s. The current-voltage (I-V) relationships were constructed by stepping in 10-mV increments from holding potential to test potentials between −100 and +130 mV for 1 s after 5-min dialysis to allow for complete exchange between the pipette solution and cytoplasm and to monitor the potential rundown of ICl(Ca) as previously documented in rabbit PASMCs (3, 5, 25, 63). ICl(Ca) was expressed as current density (pA/pF) by dividing the amplitude of the current measured at the end of the voltage-clamp step by the cell capacitance. This allowed for normalization of the current to cell size.

PCR.

At least four alternatively spliced exons (labeled “a,” “b,” “c,” and “d”) were predicted by sequence analysis for human TMEM16A (11). We examined differences in the expression pattern by RT-PCR of these hypothetical transcripts in control and MCT rat PA by designing sets of primers that would either span or anneal at one end to the target exon sequence (see Table 2). All primer sets were designed to span at least one intronic region to avoid genomic potential contaminations.

Semiquantitative PCR was performed using Gotaq Green Mastermix (Promega, Madison, WI), amplification profile: initial denaturation step at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, annealing temperature specific for each primer set for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s; the reaction was completed with a 5-min extension step. PCR product amplification was confirmed with subsequent 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and sequence analysis (Nevada Genomics Center, Reno, NV) and checked using the NCBI BLAST program. Where alternative splicing occurred, the two bands observed were quantified using densitometry software (Un-Scan It; Silk Scientific, Orem, UT) and expressed relative to each other.

Quantitative PCR.

Quantitative PCR was performed to determine the relative amount of rat TMEM16A mRNA in control and MCT-treated PA samples. Total RNA was extracted from PA samples in TRIzol reagent according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and treated with 1 U/μl DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the manufacturer's protocol for SuperScriptIII from 2 mg total RNA using 250 ng random hexamers (Invitrogen). RNAse H (20 U) was added to remove RNA complementary to the cDNA. Samples were diluted 1:5 in nuclease-free water.

Predesigned primers corresponding to rat TMEM16A, accession no. XM_219695, were purchased from SA Biosciences (Frederick, MD). These primers yielded an amplicon of 166 base pairs and spanned an exon boundary to eliminate detection of any contaminating genomic DNA. All reactions were amplified in triplicate on an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus real-time PCR system in a 20-μl total volume containing a 1× concentration SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 1 μl primer, and 2 μl diluted cDNA. Sample amplification was activated by incubation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Accumulation of PCR products was detected by directly monitoring the increase in fluorescence of the reporter dye and the threshold cycle (Ct) defined as the cycle in which fluorescence passes a fixed detection threshold. Standard curves were generated for each target gene using serial dilutions of cDNA and by plotting the log of the initial copy number in the standards vs. the Ct value. The Ct values from experimental samples were then used to calculate the amount of specific target genes relative to the standard curve. All samples were normalized to 18S rRNA amplified from the same samples to control for variations in sample quality.

Western blot analysis.

Western blotting for TMEM16A was performed on PA tissues taken from control and MCT-treated rats. The tissues were homogenized for 5 min in lysis buffer (composition: 20 mM Tris-base, 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton-X-100, 2 mM EDTA, and 1 μl/ml protease inhibitor) using an electric pestle (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm in a bench-top centrifuge (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the supernatant was collected. The proteins present in the rat PA supernatant were separated by gel electrophoresis (NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris; Invitrogen) and electroblotted onto Hybond-C Extra nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay, using bovine γ-globulin as a standard. The blots were probed with TMEM16A antibody (see below for details), followed by an Odyssey IRDye infrared secondary antibody (926–32218; Licor, Lincoln, NE). Immunodetection was carried out using the Odyssey Infrared imaging system (Licor). The collected images were analyzed by densitometry methods using Un-Scan It software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

The affinity purified primary antibodies were custom generated by Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL) using a 70-day tri-inject protocol in two New Zealand white rabbits. The following TMEM16A peptide sequences, which are conserved in both mouse and rat, were utilized: MEECAPGGCLMELCIQL, DREEYVKRKQRYEVDFNLE, and FEEEEEAVKDHPRAEYEARVLEKSLR.

Immunofluorescence and confocal imaging.

Freshly isolated rat PASMCs (fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature, and cytospun at 600 rpm for 5 min onto slides) from control and MCT-treated rats were air dried at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (10 min), rinsed three times with PBS, and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h before being incubated overnight at 4°C with prediluted primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies to TMEM16A (Abcam, ab53213). Use of this primary antibody for immunofluorescence has been successfully verified by our group (14). For control experiments, the primary antibody was omitted. After being washed three times with PBS, the slides were subsequently incubated with goat-anti-rabbit-IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A11008) diluted in blocking buffer (1:200) for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed again in PBS, the slides were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and coverslipped. Control slides were processed using secondary antibodies only. Slides were viewed and photographed on an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal scanning microscope with an Olympus 60× PlanApoN 1.42 NA oil objective. DAPI and secondary antibodies were visualized using 405 and 488 nm laser lines, respectively.

Contractile experiments.

Contractile responses of control and MCT-treated rat PA were measured using an isometric force transducer (Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI). Rings of second or third branch rat PA (usually 2 or 3 per animal) were cut from whole PA dissected away from the heart and lungs. The endothelium was removed using a continuous stream of air passed through the lumen, with successful removal of the endothelium demonstrated by the absence of an endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine (1 μM) after 5-HT (1 μM) contraction or high KCl (80 mM). PA rings were mounted in a wire myograph in 15 ml organ baths, bathed in Krebs buffer, aerated with 95% O2-5%CO2, and maintained at 37°C for the duration of the experiment. The composition of the Krebs solution was as follows (in mM): 120 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 0.6 KH2PO43−, 25 NaHCO3, 11.1 glucose, and 1.8 CaCl2 (pH 7.4 when equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2). For the high K solution, the composition was identical with the exception of NaCl and KCl, which was, respectively, 44.2 and 80 mM. After confirmation of the successful removal of the endothelium, each ring was equilibrated for 60 min in Krebs solution at basal level tension. Two successive 10- to 15-min challenges with 80 mM KCl interspersed with a 30-min washout interval followed the initial equilibration. This allowed verifying the reactivity and stability of the mounted ring. Rings that failed to reach 90% of the contraction elicited by the first KCl exposure during the second challenge were discarded.

Tissue reactivity to stretch was determined by measuring the effects of incremental steps in stretch (0.5 g) on active tension developed in response to a high K depolarizing solution (80 mM KCl-Krebs buffer) eliciting a maximal contraction. After a stable contraction was obtained following an incremental step in stretch, the high K solution was switched to normal Krebs solution containing 5.4 mM K to induce relaxation after which another increase in stretch was imposed and allowed to stabilize. The preparation was then challenged again with high K solution to measure active tension. Tension-Stretch curves were thus constructed and used to determine the optimal basal tension to be applied to PA rings in future experiments, which amounted to 80% of the maximal response to KCl (1.5 g for 2nd branch tissue and 0.75 g for 3rd branch tissues). All contractions were recorded using AcqKnowledge data acquisition software version 3.9.1 (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA).

Two successive cumulative dose-response curves to 5-HT (30 nM-3 mM; half log unit increments), first in the absence and then in the presence of 1 μM nifedipine or 30 or 100 μM niflumic acid (NFA) were performed on each ring. Separate experiments with NFA were also performed in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin to inhibit cyclooxygenases (COX) as the inhibitor was first developed as a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent acting on COX. The two dose-response curves were interspersed by a 30-min washout of 5-HT. Nifedipine or NFA were added 10 min before the addition of the first concentration of 5-HT and remained present throughout the generation of the dose-response curve. For most concentration-effect data sets, the data were least squares fitted to a sigmoidal (Logistics) function built in the software package Origin 7.5 (Northampton, MA).

Separate experiments were carried out to determine the effects of NFA on KCl-induced contractions. After a 30-min washout in normal Krebs following the second KCl-induced contraction during equilibration, the ring was next incubated with 100 μM NFA in normal Krebs for 10 min. The preparation was then exposed for a third time to 80 mM KCl in the presence of NFA. Peak contraction elicited by the KCl/NFA challenge was compared with the previous KCl-induced contraction recorded in the absence of NFA.

In another series of experiments, we examined the effects of the specific TMEM16A inhibitor T16AInh-A01 on the contraction elicited by 5-HT of conduit and intralobar PA from saline-injected and MCT-treated rats. Following equilibration in normal Krebs and two consecutive challenges with 80 mM KCl (see above), the ring was then exposed to 10 μM 5-HT to elicit a contraction. Once the contraction reached a plateau, the preparation was subsequently challenged with 10 μM T16AInh-A01 in the continued presence of 5-HT, which consistently evoked a slow relaxation in all arterial rings tested.

Source of drugs used.

Formaldehyde, BSA, glycerol, and bovine γ-globulin were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). MCT, 5-HT (serotonin), nifedipine, NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, KH2PO43−, NaHCO3, glucose, CaCl2, BAPTA, NFA, HEPES, TEA-Cl, CsCl, GTP, Na2ATP, taurine, adenosine, Triton-X-100, EDTA, and protease inhibitor were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The TMEM16A inhibitor T16AInh-A01 and indomethacin were, respectively, purchased from Asinex (Winston-Salem, NC) and EMD Millipore Biosciences (Billerica, MA).

Statistical analysis.

All pooled data are expressed as means with error bars representing means ± SE. In figures, n indicates the number of preparations or cells whereas N refers to number of animals. All data gathered in Excel were plotted using Origin 7.5 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Differences between means for various parameters measured from samples from saline-injected control rats vs. MCT-treated pulmonary hypertensive rats were analyzed with Origin software using Student's t-test for paired or unpaired data wherever appropriate or one-way ANOVA test when more than two groups were compared with a P value of <0.05 taken as statistically significant.

RESULTS

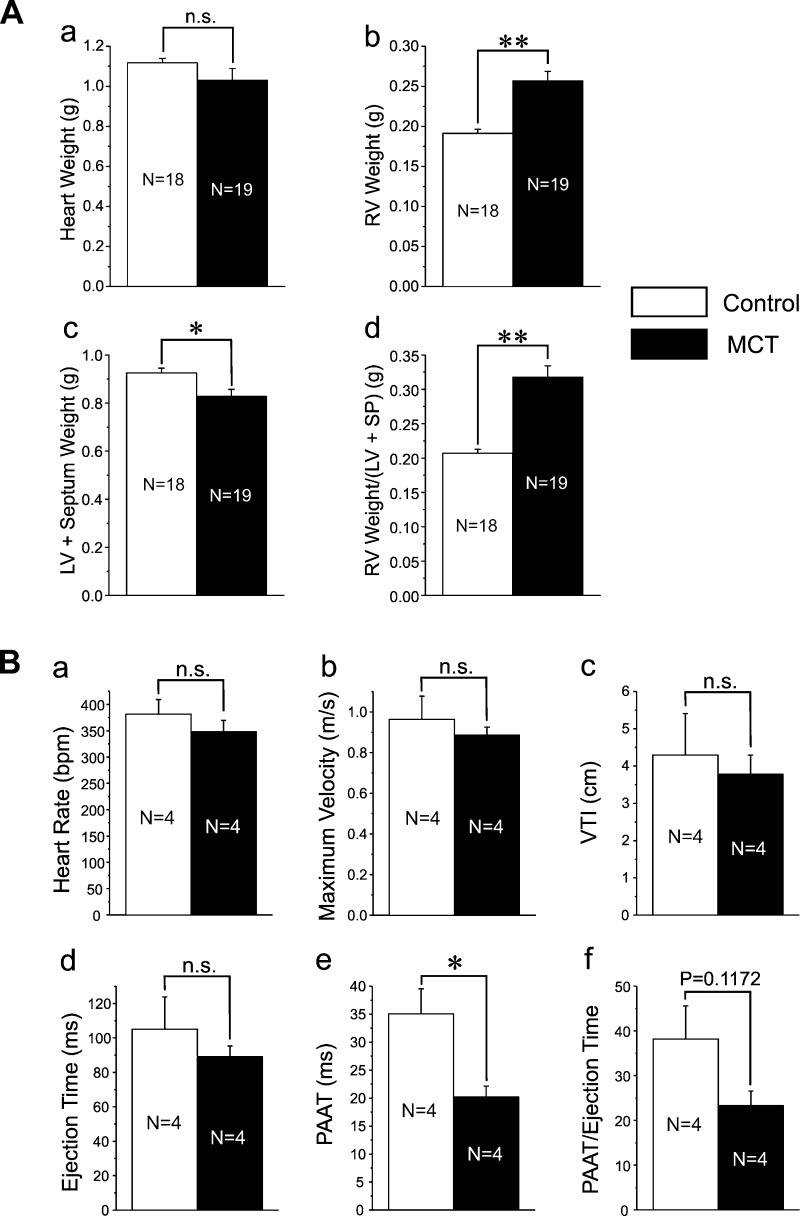

The MCT rat model of PH is a well-established model of this disease state and has been used widely in studies pertaining to PH (57). In our study, rats receiving a single intraperitoneal injection of MCT (50 mg/kg) developed RV hypertrophy and increased right ventricular wall thickness and dilatation, with little changes on the left heart. While total heart weight was not significantly altered between MCT-treated and control animals (Fig. 1Aa), RV weight (RVW; Fig. 1Ab) and the ratio of RVW to LV + SP weight (Fig. 1Ad) were significantly higher in MCT-treated vs. control rats. This contrasts with the small but significant reduction in LV + SP weight in rats treated with MCT vs. controls (Fig. 1Ac), which may be attributed to reduced physical activity of the animals due to a mechanically compromised RV. Possible changes in the pulmonary arterial circulation in response to MCT treatment were also investigated noninvasively by Doppler imaging. Pulsed-wave Doppler analysis of the PA outflow tract revealed a noticeable alteration in the shape of the flow velocity-time outflow waveform marked by the appearance of a mid-systolic notch in MCT rats, which was not apparent in control animals. There was also evidence of tricuspid regurgitation in some MCT-injected animals (data not shown). Measurements performed on such flow velocity waveform showed a significant reduction in the PAAT (Fig. 1Be) and a clear trend for a decrease in PAAT/ejection time ratio (Fig. 1Bf), while the heart rate (Fig. 1Ba), maximal flow velocity (Fig. 1Bb), VTI (Fig. 1Bc), and ejection time (Fig. 1Bd) were unchanged in pulmonary hypertension (Fig. 1Ba). These results mirror those reported for chronic hypoxia (CH)-induced PH in rats (7) and mice (59) and MCT-induced PH in rats (35) and recently suggested to represent valid indexes monitoring changes in mean systolic PA pressure in rodents (59) and humans (67). Taken together these results support the idea that we successfully developed the MCT-induced pulmonary hypertension model in the rat which exhibited the hallmark changes that include RV hypertrophy and dysfunction, changes in pulmonary arterial flow, and remodeling of the arterial wall indicative of enhanced proliferation.

Fig. 1.

Evidence for right ventricular hypertrophy and changes in pulmonary arterial (PA) outflow in monocrotaline (MCT)-induced pulmonary hypertension. A: heart weight measurements performed 3 wk postinjection for 18 control saline-injected rats and 19 rats injected with 50 mg/kg MCT. Bar graphs report changes in total heart weight (Aa), right ventricular (RV) weight (Ab), combined left ventricular (LV) and interventricular septum (SP) weights (Ac), and ratio of RV weight/(LV + SP) weights (Ad). B: pulse-waved Doppler PA outflow analysis performed on saline-injected control and MCT-injected rats. Sample volume was placed (5 mm) proximal to the pulmonary valve leaflets and aligned to maximize laminar flow. For a-f, each bar represents means ± SE for a parameter measured from 4 animals in each group. Parameters measured were the heart rate (a) in beats per min (bpm), maximum velocity in m/s (b), velocity-time integral (VTI; c), ejection time (d), PA acceleration time (PAAT; e), and PAAT/ejection time ratio (f). N, number of animals; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

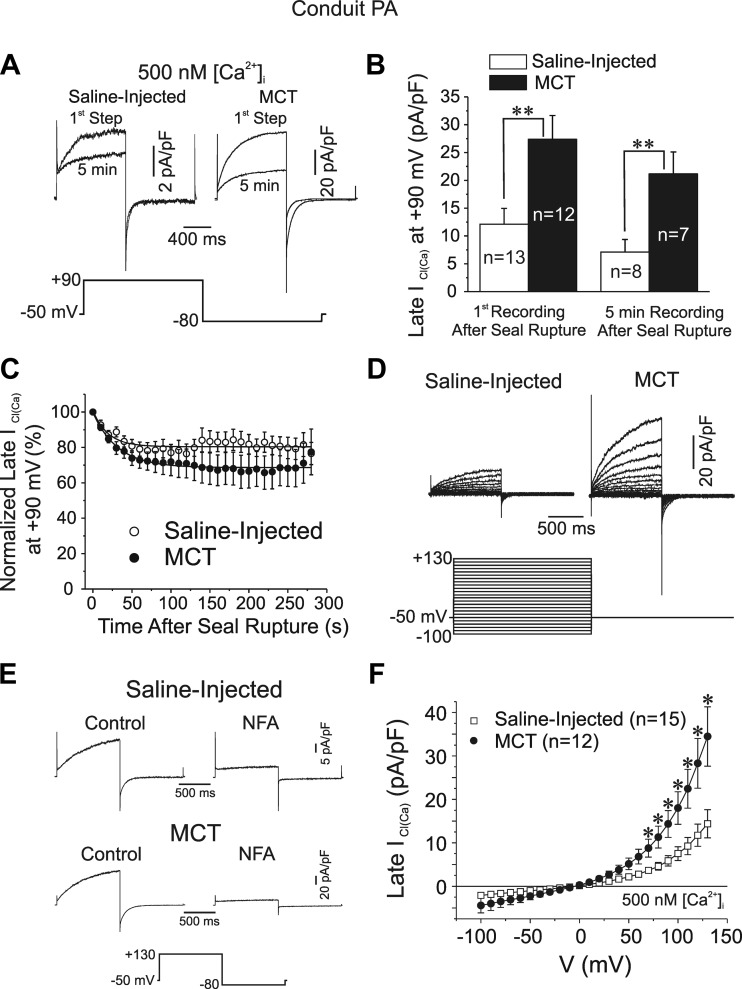

Ca2+-activated Cl− currents [ICl(Ca)] have been characterized extensively by our group using the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique in PASMCs dialyzed with 500 nM free Ca2+ concentration (3, 5, 24). The mean cell capacitance was 40% higher in PASMCs of MCT-treated relative to aged-matched control animals (data not shown; control: 20.2 ± 2.0 pF, n = 15; MCT: 28.3 ± 2.9 pF, n = 12; P < 0.05), suggesting that PASMCs hypertrophied in pulmonary hypertension. Figure 2A shows two families of superimposed ICl(Ca) recorded from conduit PASMCs isolated from a saline-injected control (left) and a MCT-treated (right) rat, respectively. One trace was recorded soon after the cell capacitance was measured (1st step), and the other chronicled after 5 min of cell dialysis. Steps to +90 mV from holding potential of −50 mV evoked typical ICl(Ca) characterized by an instantaneous current jump immediately after the capacitative current followed by a slow exponentially developing time-dependent current (τ ≈ 250–400 ms) that generally reached a steady-state level at the end of 1-s steps. Evidence for anion channel deactivation was apparent from the typical slowly decaying inward ICl(Ca) tail current (τ < 100 ms) upon repolarization to −80 mV. Although currents recorded from both groups of cells were kinetically similar, current magnitude was significantly higher in MCT cells (Fig. 2, A and B). Figure 2, B and C, also shows that ICl(Ca) was appreciably smaller after 5 min of cell dialysis in both cell groups, an observation consistent with a rundown process that in rabbit PASMCs dialyzed with ATP was shown to involve at least one phosphorylation step regulated by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, calcineurin, and PP1/PP2A (3, 5, 24, 25). Figure 2C shows that ICl(Ca) rundown at +90 mV was similar in the two groups and followed an exponential time course that stabilized within 2 min at ∼70–80% of the initial level recorded after seal rupture, suggesting that the regulation of ICl(Ca) appeared to be similar in pulmonary hypertensive compared with control animals although that was not specifically tested. ICl(Ca) recorded from a wide range of membrane potentials was again significantly larger in smooth muscle cells from conduit proximal pulmonary arteries of MCT-treated rats vs. controls (Fig. 2D). Kinetic analysis revealed no significant differences between the two groups of cells in ICl(Ca) activation and deactivation kinetics at +90 and −80 mV, respectively (time constant of activation τact at +90 mV: control: 313 ± 26 ms, n = 11, MCT: 281 ± 21 ms, n = 14, P < 0.05; time constant of deactivation τdeact at −80 mV: control: 88.1 ± 7.7 ms, n = 11, MCT: 95.1 ± 5.8 ms, n = 14, P < 0.05). NFA (100 μM), a putative ClCa channel blocker (41), potently inhibited currents from both cell groups (Fig. 2E). This was consistently observed in at least four other PASMCs in each group of animals. Figure 2F shows that mean currents in both study groups reversed near the predicted equilibrium potential for Cl− in our conditions (∼0 mV) and displayed typical outward rectification due to the inherent voltage-dependent gating of the channel (3, 24, 41). Interestingly, the slope conductance of ICl(Ca) within the physiological range of membrane potentials was 2.16-fold higher in MCT cells compared with control myocytes, suggesting a greater contribution of ClCa channels in determining resting membrane potential.

Fig. 2.

Properties of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in smooth muscle cells of proximal conduit PA from MCT-treated rats. A: representative whole cell Ca2+-activated Cl− current [ICl(Ca)] traces recorded from pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) from a saline-injected control rat (top left) and a MCT-injected rat (top right). “1st Step” and “5 min” traces, respectively, refer to the very first current recorded immediately after measuring cell capacitance and that registered after 5 min of cell dialysis with a pipette solution containing 500 nM free Ca2+ concentration (500 nM [Ca2+]i). All traces were elicited by the voltage-clamp protocol shown below the traces. Note the different calibrations for the 2 sets of superimposed currents. B: effects of MCT treatment on mean ICl(Ca) amplitude measured at the end of 1-s pulses to +90 mV in PASMCs from saline (empty bars)- and MCT-injected (filled bars) rats soon after seal rupture (left bars) and after 5 min of cell dialysis (right bars). C: mean time course of changes of normalized late ICl(Ca) at +90 mV following cell rupture in PASMCs from saline (control; ○)- or MCT-injected (●) animals. All currents were normalized to the first current recorded at time = 0. Voltage-clamp protocol used to evoke ICl(Ca) was identical to that shown in B and was repeated every 5 s. The 2 lines are least-squares exponential fits to the mean data. The 2 time courses were not statistically different from one another. Control: n = 13; MCT: n = 12. D: representative families of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents recorded with a pipette solution containing 500 nM Ca2+ in freshly dispersed PASMCs from proximal conduit arteries from a saline-injected rat (left traces) and a rat injected with MCT (right traces) to induce pulmonary hypertension. All currents were evoked by the voltage-clamp protocol shown below the traces. E: sample traces from 2 representative experiments showing the potent inhibition of ICl(Ca) by 100 μM niflumic acid (NFA; ∼5 min) in PASMCs dialyzed with 500 nM Ca2+ from a saline (top)- and a MCT-injected (bottom) rat. Currents were evoked by the protocol shown below the traces. F: mean current-voltage relationships for ICl(Ca) recorded in PASMCs from saline-injected controls and MCT-treated rats. ICl(Ca) was measured at the end of 1-s steps to voltages ranging from −100 to +130 mV from holding potential of −50 mV (protocol identical to that in A). For B and F, n = number of cells; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001, statistically significant.

We next determined whether ICl(Ca) was also affected in PASMCs from smaller intralobar arteries (∼200–300 μm in lumen diameter). The results were very similar to those of proximal conduit vessels including a higher cell capacitance (control: 10.8 ± 0.8 pF, n = 15; MCT: 15.8 ± 1.5 pF, n = 6; P < 0.01; data not shown) and ClCa conductance (∼2-fold; Fig. 3, A, C, and D), and no significant difference in rundown of ICl(Ca) in cells from MCT-treated vs. control rats (Fig. 3B) or kinetics of activation and deactivation at +90 and −80 mV, respectively (τact at +90 mV: control: 330 ± 42 ms, n = 9, MCT: 223 ± 26 ms, n = 6, P > 0.05; τdeact at −80 mV: control: 88.8 ± 11.4 ms, n = 9, MCT: 88.8 ± 8.1 ms, n = 6, P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Properties of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in smooth muscle cells of intralobar PAs from MCT-treated rats. A: effects of MCT treatment on mean ICl(Ca) amplitude measured at the end of 1-s pulses to +90 mV in PASMCs from saline (control; empty bars)- and MCT-injected (filled bars) rats soon after seal rupture (left bars) and after 5 min of cell dialysis (right bars). B: mean time course of changes of normalized late ICl(Ca) at +90 mV following cell rupture in PASMCs from saline (control; ○)- or MCT-injected (●) animals. All currents were normalized to the first current recorded at time = 0. Voltage-clamp protocol used to evoke ICl(Ca) was identical to that shown in Fig. 2A and was repeated every 5 s. The 2 time courses were not statistically different from one another. C: representative families of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents recorded with a pipette solution containing 500 nM free Ca2+ in freshly dispersed PASMCs from intralobar pulmonary arteries from a saline-injected rat (left traces) and a rat injected with MCT (right traces) to induce pulmonary hypertension. All currents were evoked by the voltage-clamp protocol shown below the traces. D: mean current-voltage relationships for ICl(Ca) recorded in PASMCs isolated from intralobar PA of saline-injected controls and MCT-treated rats. ICl(Ca) was measured at the end of 1-s steps to voltages ranging from −100 to +130 mV from holding potential of −50 mV (protocol identical to that in C). For A, B, and D, n = number of cells; *P < 0.05.

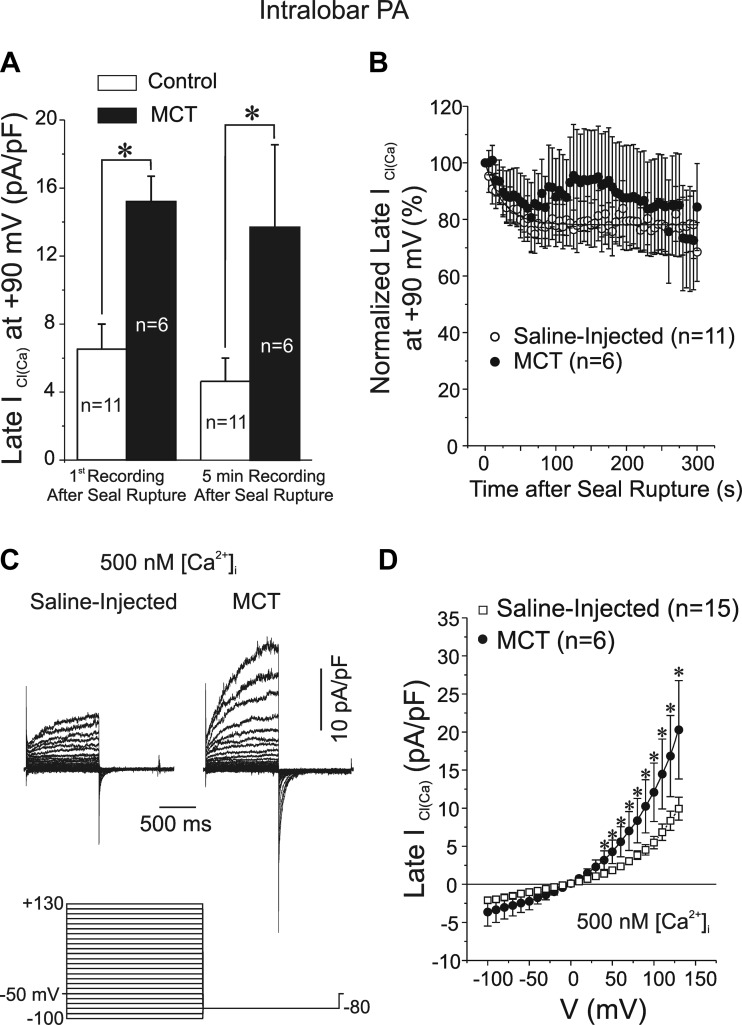

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis showed the existence of transcripts consistent with TMEM16A in PA from both groups of animals and revealed higher levels of expression in conduit (data not shown) and intralobar PA (Fig. 4A) from MCT- vs. saline-treated rats. This was established by quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis showing significantly higher expression (>2-fold) of TMEM16A normalized to a ribosomal 18S transcript in conduit (Fig. 4B) and intralobar (Fig. 4C) PA.

Fig. 4.

Changes in TMEM16A mRNA expression of conduit and intralobar pulmonary arteries in MCT-induced pulmonary hypertension. A: semiquantitative RT-PCR experiment showing increased expression of TMEM16A mRNA in a pulmonary artery from 2 MCT-treated rats vs. that from 2 aged-matched saline-injected controls (C) as labeled. Notice the presence of 2 bands in each lane consistent with the predicted rat TMEM16A including or excluding spliced variant d (Table 1). NTC, nontemplate control. B and C: quantitative RT-PCR for TMEM16A mRNA transcript expression relative to the ribosomal housekeeping gene 18S in conduit and intralobar PA, respectively, from control saline-injected (empty bars) and MCT-treated (filled bars) animals. D: sample agarose gels highlighting mRNA expression of spliced variants b (top) and d (bottom) of TMEM16A in pulmonary arteries from a saline-injected control and a MCT-treated animal (MCT). Each spliced variant was interrogated with 2 different sets of primers (Table 1), 1 spanning the alternatively spliced exon (lanes 2 and 3) and 1 in which 1 of the 2 primers was designed to anneal to the target exon (lanes 4 and 5). Primers sets spanning or annealing to the target exon resulted in a double or a single band, respectively, with the predicted number of base pairs (bp) indicated below each gel. E: graphs showing the effect of PCR cycle number on the amplification of TMEM16A transcripts of pulmonary arteries from a saline-injected control (■, ☐) and a MCT-injected rat (●, ○). Amplified cDNA transcripts either contained (top band; ■, ●) or excluded (bottom band; ☐, ○) the alternatively spliced exon for variants b (a) and d (b). These experiments served to determine the optimal PCR cycle number allowing for a more accurate determination of the relative expression of the alternatively spliced exons. The 25 PCR cycles were subsequently used for this analysis (arrows in a and b) as it lied in the ascending linear portion of amplification for both spliced exons. All smooth lines passing through the data points are least squares Boltzmann fits. F: mean relative percent expression after 25 cycles of PCR of alternatively spliced exons b (left bars) and d (right bars) pooled from pulmonary arterial samples from saline-injected control (open bars) and MCT-treated rats (filled bars). N = number of animals; *P < 0.05; n.s.: not significant.

TMEM16A is known to undergo alternative splicing with the regulated expression of at least four exons labeled exons a, b, c, and d (11, 19), and the insertion of these different variants profoundly alters the calcium sensitivity and biophysical properties of the channel (18, 19, 45, 64). Analysis of TMEM16A expression in pulmonary arteries from both study groups revealed that primers designed to anneal to spliced variant a always resulted in a single band that was confirmed by sequencing to correspond to rat TMEM16A exon 1 (data not shown). This does not exclude the possibility that a minimal TMEM16A transcript isoform excluding this exon [e.g., see Ferrera et al. (19)] is expressed in rat PA smooth muscle but this aspect was not investigated. While spliced variant c was found to be constitutively expressed in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle from both groups of animals and is thus always transcribed (always yielding a single band that included spliced variant c when using primers spanning the corresponding exon; data not shown), transcripts corresponding to exons b and d were found to undergo alternative splicing. The above profile of alternative splicing of TMEM16A is consistent with that reported by another group in the same preparation and species (44). We ascertained whether the expression of spliced variants b and d relative to the total level of TMEM16A transcript was altered by the development of PH. Figure 4D shows that MCT-induced PH was associated with an apparent increase in the expression of transcripts containing exons b and d (Fig. 4D, lanes 2 and 3). This is particularly evident when examining the results obtained with primer sets where one primer annealed to the target exon (Fig. 4D, lanes 4 and 5). We performed calibrated densitometry measurements to determine the relative expression of TMEM16A transcripts comprising or excluding exons corresponding to spliced variants b and d (Fig. 4, Da and Db). The optimal number of PCR cycles leading to expression levels for each transcript being measured within the linear portion of PCR amplification was determined for PA mRNA samples extracted from saline- and MCT-injected rats. Upper and lower band densities in Fig. 4E reflect transcript levels comprising or excluding the exon of interest. Based on Boltzmann sigmoidal fits to the data, we chose to perform a comparison of alternatively spliced variant expression at the 25 PCR cycle mark for both spliced variants (arrows; Fig. 4E). Analysis of the “relative” expression of these two variants showed that the percentage of transcripts of conduit PA containing exon b was significantly larger in the MCT-treated group while the relative expression of exon d was not different (Fig. 4F).

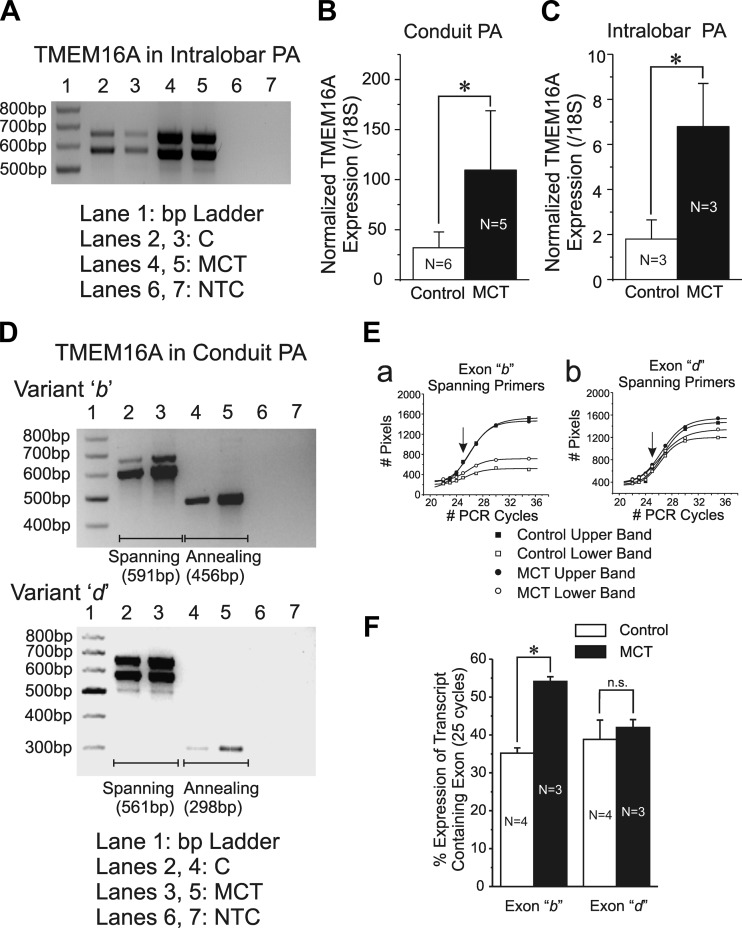

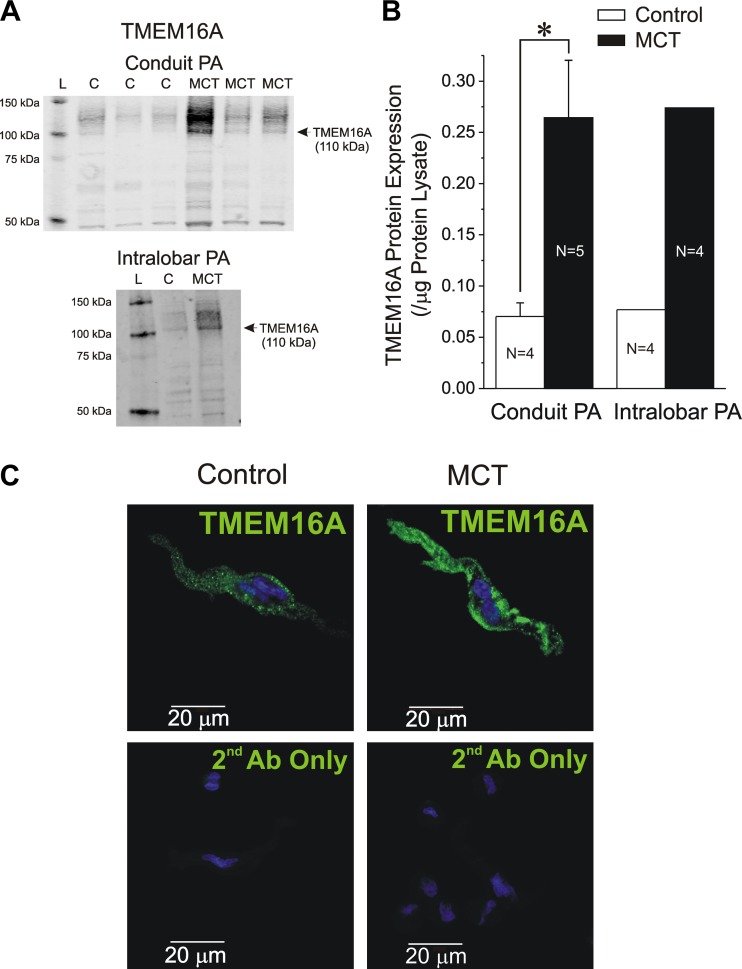

Western blot experiments were next conducted to determine whether TMEM16A protein levels of conduit and intralobar PA were altered in pulmonary hypertensive rats relative to aged-matched controls. A custom-made rabbit polyclonal antibody was used to identify TMEM16A (see materials and methods). Figure 5A shows the resulting immunoblots obtained from total protein lysates from conduit (top gel; 3 representative samples from each group) and intralobar (bottom gel) PA from saline- and MCT-injected rats. For intralobar PA, four vessels for each group of animals were pooled due to the low amounts of protein extracted from these small blood vessels. A distinctive band at ∼110 kDa and consistent with the predicted molecular mass of TMEM16A was accompanied by more diffuse immunostaining at higher molecular mass that may be explained by the expression of multiple spliced forms (14, 44) and by the fact that TMEM16A possesses at least one predicted glycosylation site (27). Western blot analysis revealed that similar to mRNA levels the expression of TMEM16A protein was higher in the MCT vs. control group for conduit and resistance PA (Fig. 5, A and B). Immunofluorescence and confocal imaging of freshly isolated PASMCs from both groups of animals using a specific commercial TMEM16A antibody (14) (Abcam 53213) indicated that a significant fraction of the protein visualized in single cells is located at the plasma membrane with a slight tendency for immunofluorescence intensity to be higher in cells from MCT-treated rats although this was not analyzed quantitatively (Fig. 5C; saline: n = 22; MCT: n = 25). Overall, these data show that ClCa and the expression of TMEM16A at the mRNA and protein levels are augmented in PASMCs from PH rats.

Fig. 5.

TMEM16A protein is upregulated in conduit and intralobar pulmonary arteries from MCT-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. A: Western blot analysis of TMEM16A protein expression in conduit (top gel) and intralobar (bottom gel) PA from saline-injected control and MCT-treated rats. Top gel: immunoblots from 3 control and 3 MCT pulmonary arteries; bottom gel: generated by pooling intralobar PA from 4 saline-injected (C) and 4 MCT-injected rats. All blots were probed with a custom-generated rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against 3 epitopes found in mouse and rat TMEM16A protein as described in materials and methods. For both gels, a major band at ∼110 kDa and more diffuse higher molecular mass bands displayed significantly higher levels in the MCT vs. C lane. The C and MCT lanes were each loaded with 20 μg of lysate protein. L, molecular mass ladder. B: pooled Western blot densitometry measurements for TMEM16A expression in conduit (left bars) and intralobar PA (right bars) from control (open bars) and MCT-treated rats (closed bars). For intralobar PA, total protein lysates from four animals in each group were combined for analysis. N = number of animals. *P < 0.05. C: immunocytochemical detection of TMEM16A protein (green; Abcam 53213 antibody) in freshly isolated PASMCs from control and MCT-treated rats (top images as labeled). Bottom images: lack of TMEM16A staining when the cells were exposed to secondary antibody only (2nd Ab Only). For all images, nuclei appear in blue and were stained with bisbenzamide.

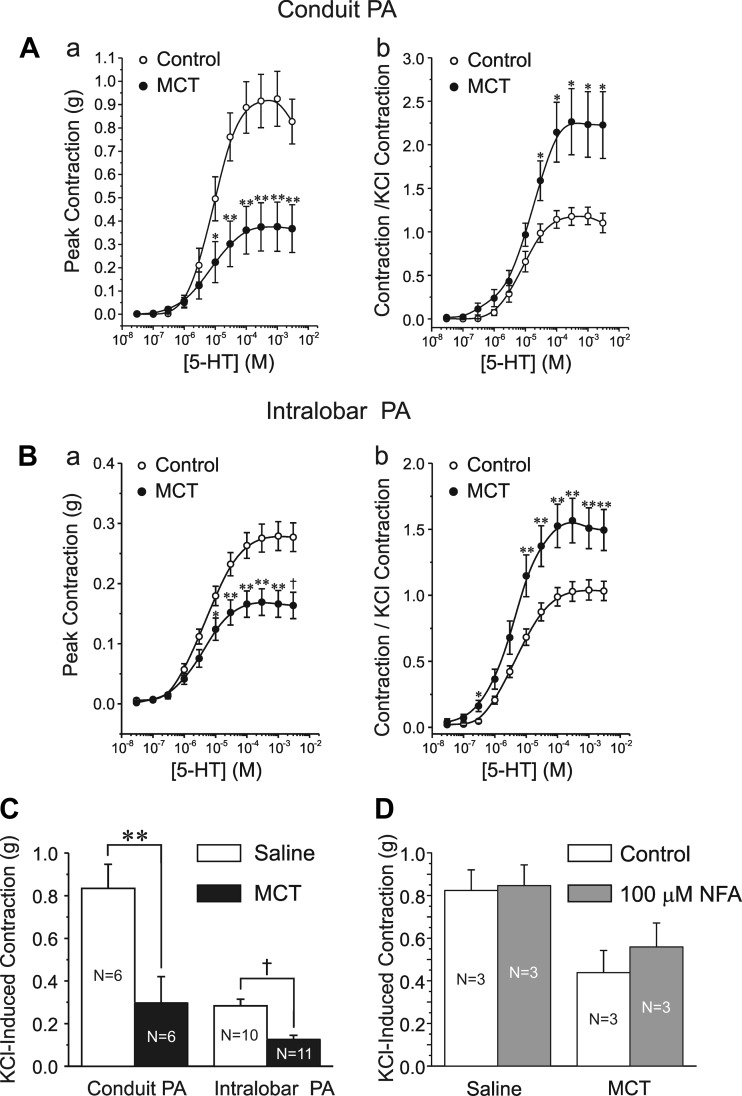

The potential functional impact of enhanced ClCa conductance was compared in intact PA from MCT and control rats. The maximal contractile response of conduit and intralobar PA from rats injected with MCT for 14 days was reduced compared with the saline controls (Fig. 6, Aa and Ba). This is similar to other reports showing a delayed (> 7 days) reduction of peak contraction to agonists that followed an early transient increase in contraction a few days post-MCT injection (1, 56) and is largely attributable to a significant reduction in the KCl-induced contraction (Fig. 6C). However, when normalized to the response elicited by 80 mM KCl, the 5-HT-induced contraction was significantly higher than that seen in PA from control animals (Fig. 6, Ab and Bb). Moreover, PA from pulmonary hypertensive rats displayed increased sensitivity to 5-HT, especially near the threshold for contraction (10−8-10−6 M).

Fig. 6.

Changes in the contractile phenotype of rat pulmonary arteries induced by MCT. A and B: mean cumulative dose-response curves to serotonin (5-HT) of the contraction of conduit and intralobar PA, respectively, from saline-injected control (○) and MCT-injected (●) rats. For A and B, a plots the magnitude of the absolute peak contraction relative to baseline, whereas b plots the same data normalized to the maximal KCl (80 mM)-induced contraction. A: 6 animals per group, 2 rings per animal; B: control, 10 animals (2 rings per animal); MCT, 11 animals (2 rings per animal). C: bar graph showing the mean changes in the KCl-induced contraction of conduit (left bars) and intralobar (right bars) PA from control (black) and MCT-treated (red) rats. D: bar graph showing the effects of NFA (white bars) on the peak contraction evoked by 80 mM KCl in conduit pulmonary arteries derived from saline-injected (left bars) or MCT-injected rats. For C and D, N = number of animals (2 rings per animal). For A-D, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; †P < 0.001.

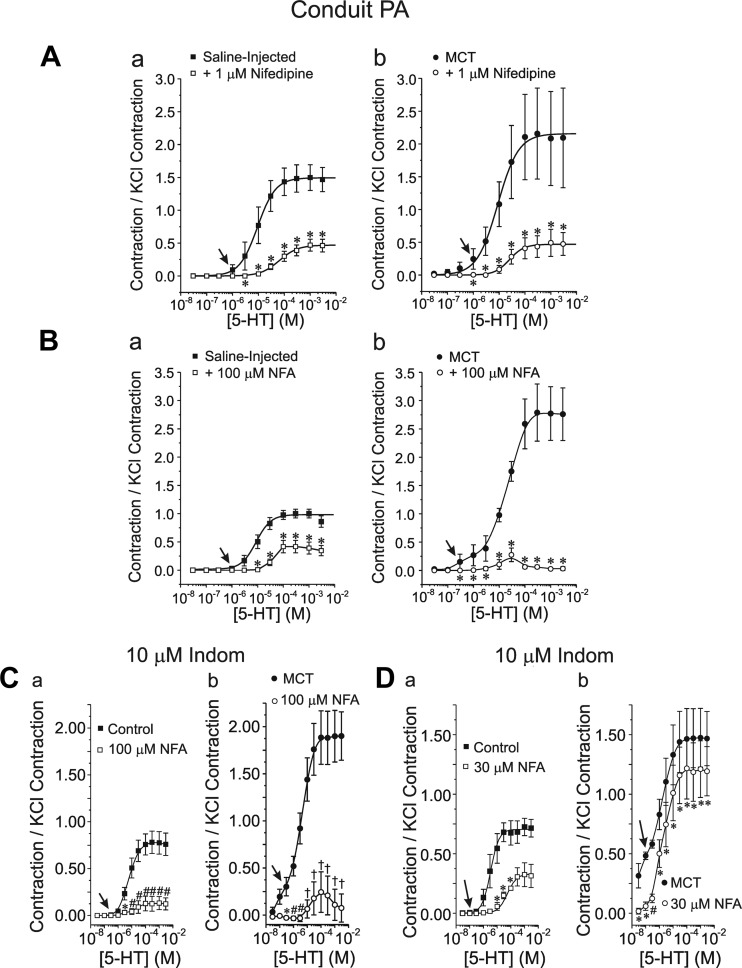

The increased potency of the vasoconstrictor (contraction to 5-HT normalized to the KCl-induced contraction) was associated with a heightened response to the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine (1 μM; Fig. 7, Aa and Ab) and the archetypal ClCa channel blocker NFA (100 μM; Fig. 7, Ba and Bb) in MCT-treated animals. In the latter case, NFA exerted a profound inhibition of the contraction evoked by 5-HT for concentrations >5 × 10−4 M. The greater vasorelaxation potency of NFA relative to nifedipine in conduit PA from MCT rats at 5-HT concentrations higher than 10 μM was not due a potential effect of NFA on COX as the response to the ClCa inhibitor was similar in both large and small arteries when the arterial rings from both animal groups were preincubated with the COX inhibitor indomethacin (10 μM; Fig. 7, Ca and Cb). Moreover, the two inhibitors significantly attenuated the contractile response to low concentrations of 5-HT in MCT-treated animals, an effect that was not apparent in control animals (e.g., please note the significant relaxation by nifedipine or NFA to 300 nM 5-HT was apparent for MCT- vs. saline-injected animals; see arrows). A potent vasorelaxation by a lower concentration of NFA (30 μM) in the presence of indomethacin was also detected in PA from both study groups (Fig. 7, Da and Db), with again a very potent relaxation at very low concentrations of 5-HT in PA from MCT rats. However, the magnitude of the relaxation mediated by 30 μM NFA was clearly attenuated relative to that elicited by 100 μM NFA in both groups. Of importance was the observation that 100 μM NFA produced no effect on the contraction of conduit PA evoked by 80 mM KCl in the two groups of animals (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 7.

Altered sensitivity of the 5-HT-induced contraction of conduit PA to L-type Ca2+ channel and ClCa inhibitors in MCT-induced PH. A: effects of 1 μM nifedipine on the dose-response relationships of the PA contraction to 5-HT normalized to the KCl-induced contraction in saline-injected control (a) and MCT-treated (b) rats; ☐, ■ and ○, ● in a and b represent data obtained in the absence and presence of the drug, respectively. B: nomenclature identical to A except that these experiments tested the effects of 100 μM NFA in the 2 groups of animals. C: nomenclature identical to A except that these experiments tested the effects of 100 μM NFA in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin (Indom) in the 2 groups of animals. D: nomenclature identical to A except that these experiments tested the effects of 30 μM NFA in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin in the 2 groups of animals. For A–D, arrows highlight the appearance of significant contractions in MCT-injected animals at low 5-HT concentrations relative to their control counterpart. For A–D, data were collected from 6 rings, 2 from each of 3 animals. For A–D, *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01; †P < 0.001.

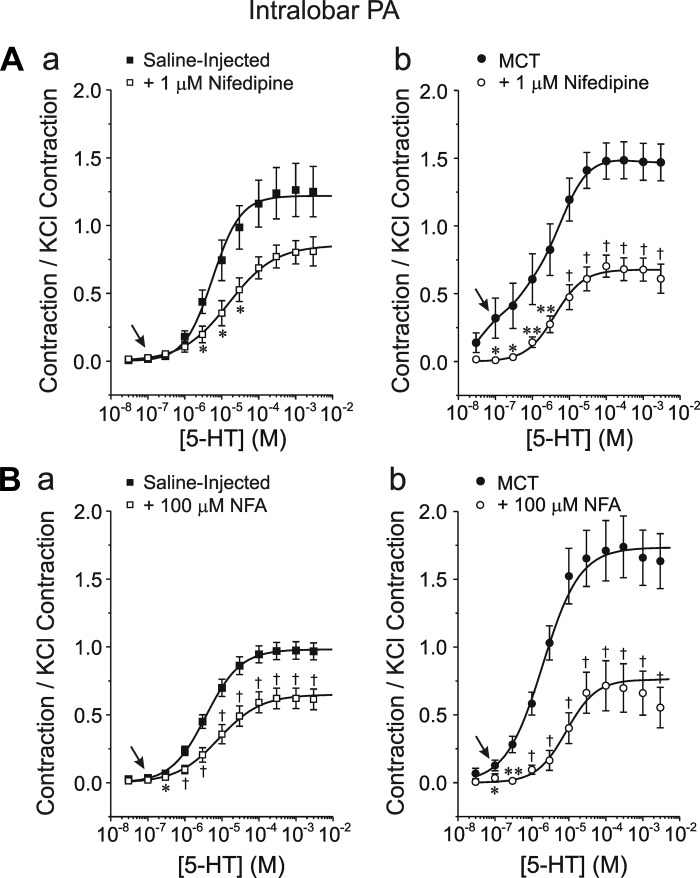

As for conduit PA, small arteries from MCT-treated animals also exhibited increased sensitivity to 1 μM nifedipine (Fig. 8, Aa and Ab) and 100 μM NFA (Figs. 8Ba and 9Bb) marked by a greater potency of causing relaxation at low (notice again differences in the range of 100 nM to 1 μM; arrows) and high 5-HT concentrations. In a limited number of experiments, similar responses were obtained with 100 μM NFA after preincubating the preparation with 10 μM indomethacin (n = 2 for each group).

Fig. 8.

Altered sensitivity of the 5-HT-induced contraction of intralobar PA to L-type Ca2+ channel and ClCa inhibitors in MCT-induced PH. Nomenclature is identical to that of Fig. 7, A and 7B. Aa: six rings, 3 animals; Ab: 14 rings, 7 animals. Ba: 10 rings, 5 animals; Bb: 14 rings, 8 animals. Arrows highlight the appearance of significant contractions in MCT-injected animals at low 5-HT concentrations relative to their control counterpart. For all A and B, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; †P < 0.001.

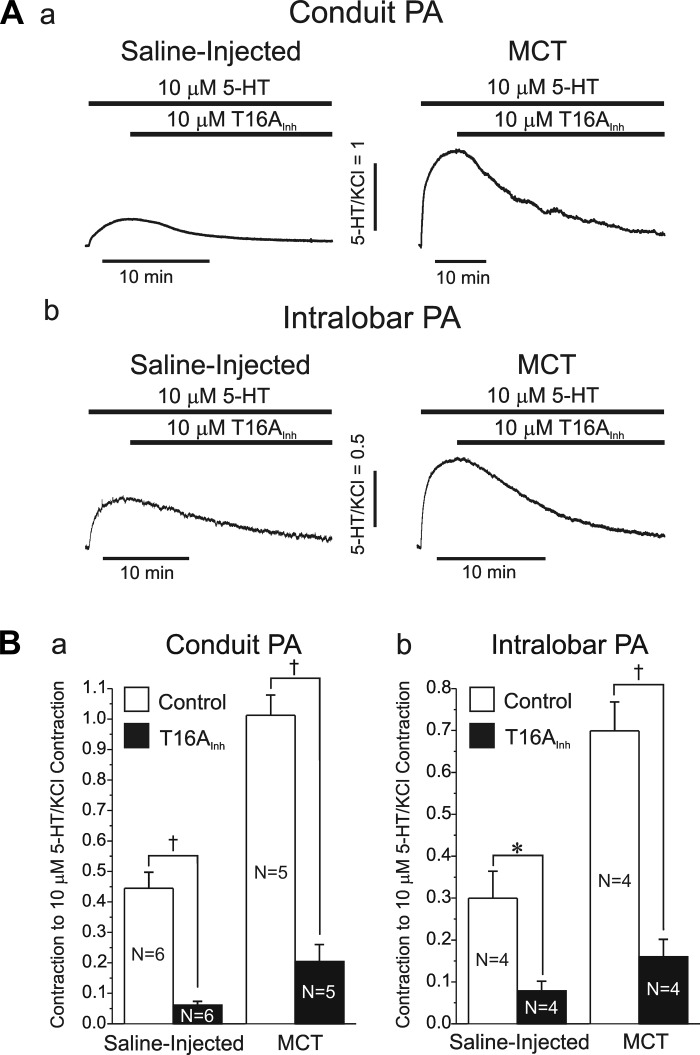

Fig. 9.

Altered sensitivity of the 5-HT-induced contraction of conduit and intralobar pulmonary arteries to the specific ClCa/TMEM16A inhibitor T16AInh-A01 in MCT-induced PH. A: typical isometric force recordings illustrating the vasorelaxation mediated by the specific TMEM16A inhibitor T16Inh-A01 (T16AInh, bottom thick bar) on the contraction of conduit (a) and intralobar (b) pulmonary arterial rings evoked by 10 μM 5-HT (top thick bar) from saline-injected control (left trace) and MCT-treated (right trace) rats. All contractions were normalized to that elicited by 80 mM KCl (vertical calibrations). B: bar graphs summarizing pooled data from similar experiments to those shown in A. Each bar represents the means ± SE contraction to 5-HT normalized to the KCl-induced contraction in each PA ring; a and b: reflect data obtained in conduit and intralobar PA rings, respectively, as indicated. For a and b, *P < 0.05 and †P < 0.001. Please note that for a and b, the contraction evoked by 5-HT of PA rings from MCT rats was significantly higher than that of control animals. However, the level tone of PA rings from MCT rats remaining in the presence of T16AInh-A01 and 5-HT was not significantly different than that measured in PA rings from saline-injected control rats. For A and B, N = number of animals.

Figure 9 shows the results of a subsequent series of experiments examining the effects of T16AInh-A01, a recently developed specific ClCa/TMEM16A inhibitor (15, 16, 48), on the contraction of conduit and intralobar PA from the two groups of animals. Figure 9A shows representative tension recordings from conduit (Fig. 9Aa) and intralobar (Fig. 9Ab) PA from saline-injected control (left traces) and MCT-treated (right traces) animals. Consistent with the data presented in Figs. 6–8, exposure to 10 μM 5-HT elicited a larger contraction (normalized to the KCl-induced contraction) in MCT-injected vs. control rats, which is also reflected in the mean data shown in Fig. 9B (compare open bars in each panel). Figure 9A also shows that the application of 10 μM T16AInh-A01 in the continued presence of 5-HT initiated a very slow but potent relaxation in all preparations studied. Mean data in Fig. 9B show that T16AInh-A01 produced considerable relaxation in all groups tested and of similar relative magnitude to that exerted by 100 μM NFA (Figs. 7, B and C, and 8B). Moreover, the contraction remaining in the presence of the inhibitor was not significantly different between PA from control and pulmonary hypertensive animals, suggesting that the inhibitor suppressed the component of contraction that was enhanced in pulmonary hypertension.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows for the first time that Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in smooth muscle cells from conduit and intralobar pulmonary arteries were significantly greater in the widely used MCT rat model of PH than control animals. These observations were correlated with an increase in the expression of TMEM16A, and its translated protein in the same vessels. Consistent with the biophysical and molecular studies, functional experiments revealed an increased sensitivity to the putative ClCa blockers NFA and T16AInh-A01 of the contraction elicited by serotonin. These results support the hypothesis that enhanced ClCa/TMEM16A channel activity contributes to the enhanced vasoconstriction to agonists of pulmonary arteries in the pulmonary hypertensive state elicited by a single dose of MCT. Our findings mirror those of a recent report showing similar results obtained with the CH model of PH in the same species (further discussed below; Ref. 58).

The MCT models, an acute toxic model of pulmonary hypertension (57) and the CH model in the rat, are still the most commonly used animal models of pulmonary hypertension (10, 52, 57). Both models are associated with many, but not all, of the changes occurring in human pulmonary hypertension, which include alterations in reactivity of pulmonary arteries to vasoconstrictors and vasodilators, remodeling of the blood vessel leading to a reduced lumen diameter due to wall thickening by increased cell proliferation, increased thrombosis and inflammation, and significant RV hypertrophy and dysfunction. Although the precise mechanism of action of MCT is still unclear, it is hypothesized that a pyrrole metabolite of MCT causes a rapid and selective destruction of the endothelium in the pulmonary vasculature (28, 30, 32, 36, 39, 46, 47, 61). Since the endothelium is responsible for producing or converting into their final form many of the vasoactive and antithrombotic factors, the chemically induced imbalance of factors eventually produces functional and structural changes of both proximal and distal PA vessels that increase pulmonary arterial pressure (>30 mmHg) due to increased resistance to flow and the progressive development of RV hypertrophy and failure. In the rat, no apparent neo-intimal obstruction is observed in distal arteries (57). The model is reasonably curable by a large number of agents, which is not the case in humans (1, 21, 33, 34, 54). Therefore, data obtained with the MCT model have to be interpreted with caution when attempting to extrapolate them to human pulmonary arterial hypertension. In spite of its limitations, the MCT model has proven to be a valuable research tool in preclinical studies to investigate new therapeutic paradigms as current pharmacological treatments that do offer significant benefits to humans with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Our experiments that examined the changes in expression of TMEM16A suggest that the relative increase in ClCa conductance of PASMCs detected in pulmonary hypertensive rats is likely due to a proportional increase in the amount of translated TMEM16A protein. The majority of the protein detected by Western blot is most likely primarily distributed in the medial layer of the artery as we previously found little or no evidence of TMEM16A immunostaining in the adventitial and endothelial cell layers using the same antibody (14). Although an increase in TMEM16A protein synthesis in PH cannot be ruled out, it is also possible that higher TMEM16A levels might have resulted from increased TMEM16A mRNA transcript levels. Whether the similar relative increase in TMEM16A transcript levels (∼2- to 3-fold) is meaningful in determining the translation of TMEM16A or is coincidentally related to the timing of the measurements must be interpreted with caution as the genetic factors regulating the expression of this gene are still unknown. It is also possible that membrane trafficking or surface membrane expression of TMEM16A might have been altered by the MCT treatment but yet again the processes regulating the turnover rate of this protein are presently undefined and will require further investigation. A similar increase in TMEM16A expression at the mRNA and protein levels was also detected in pulmonary arteries from CH rats (58).

Four exons of TMEM16A are alternatively spliced (identified as exons a, b, c, and d) producing different variants (11) that influence its expression (11) and biophysical properties (18, 19, 64). While the role of spliced variant d is relatively unknown except for the reported deceleration of activation and deactivation kinetics when this transcript is present (45), spliced variant b (22 a. a.) and the short variant c (EAVK) were suggested to regulate the Ca2+ sensitivity and voltage dependence of the channel (18, 19, 64). Since spliced variants a and c are always expressed in vascular myocytes (this study and Refs. 14, 44), we examined the profile of expression of spliced variants b and d in two groups of animals and found that PA from MCT-treated rats displayed higher levels of transcripts expressing the variant b while the variant d was unchanged. Our data suggest that the enhanced expression of transcripts comprising this exon would tend to reduce the Ca2+ sensitivity of TMEM16A (18) in PH. Clearly, a thorough analysis of the Ca2+ dependence of ICl(Ca) in pulmonary hypertension is required before a definitive conclusion can be drawn about the potential role of spliced variant b in PH. Finally it is known that the closure rate of ClCa is particularly sensitive to membrane potential, especially at low to intermediate levels of [Ca2+]i, with membrane hyperpolarization accelerating deactivation kinetics (3, 24, 41). We found that the kinetics of activation and deactivation of ICl(Ca) were unchanged in cells from MCT-treated compared with control rats. Although this could suggest that the voltage sensitivity of the channels was unchanged, we need to be cautious in our interpretation because concomitant changes in voltage and Ca2+ sensitivity could lead to an apparent lack of effect on tail current deactivation that only a comprehensive analysis over a wide range of voltages and internal Ca2+ levels could resolve. In contrast to our results with the MCT model, Sun et al. (58) reported a significant increase in the time constant of deactivation over a wide range of voltages in PA myocytes from CH relative to controls while activation kinetics were unchanged.

Niflumic acid is a relatively potent inhibitor of ClCa channels (41) and the most frequently used compound to investigate the physiological role of ClCa channels in determining vascular smooth muscle tone (37, 40, 41). At concentrations between 10 and 100 μM, NFA was shown to cause relaxation of several types of arteries stimulated by contractile agonists while having no direct inhibitory effect on L-type Ca2+ current, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization induced by an agonist (41), KCl-induced contractions in rat pulmonary arteries (69) and myogenic tone in rabbit mesenteric arteries (51). NFA (100 μM) did not affect the nonselective cation current evoked by activation of store-operated Ca2+ entry with cyclopiazonic acid in rabbit PA myocytes (2) NFA reversed the depolarization induced by 5-HT in rat PASMCs (69), supporting an important role for ClCa channels in electromechanical coupling. In this study, 100 μM NFA similarly inhibited 5-HT-induced contractions of proximal and distal PA from control and MCT-treated animals and to a similar degree to that produced by the specific Ca2+ channel inhibitor nifedipine, except for at higher concentrations of 5-HT in conduit PA from MCT-injected animals where the potency of NFA exceeded that of nifedipine. Similar to Oriowo (49), 100 μM NFA were more potent at inhibiting the contraction to 5-HT in PA from MCT relative to control rats, an observation consistent with enhanced ICl(Ca) and TMEM16A expression in conduit and resistance pulmonary arteries. This effect was particularly prominent at low concentrations of 5-HT (30–100 nM) where NFA and nifedipine produced virtually identical effects, essentially obliterating a component of contraction that was absent in PA from control animals. Although overall less potent than that produced by 100 μM NFA, a lower concentration of the blocker (30 μM) produced a similar potent relaxation at low concentrations of 5-HT in proximal and distal arteries from pulmonary hypertensive animals. NFA (100 μM) had no effect on the contraction caused by 80 mM KCl in PA from both groups of animals supporting the contention that the inhibitor did not produce vasorelaxation of 5-HT-induced contractions by directly inhibiting L-type Ca2+ channels or by interfering with the contractile machinery. However, NFA and other fenamates have been shown to exert nonspecific effects bearing major implications for interpretation of physiological data depending on the cell type in which they are tested. Fenamates were reported to stimulate the human slow delayed rectifier K+ channel (IsK) expressed in Xenopus oocytes (9), a delayed rectifier K+ current in canine jejunal smooth muscle cells (17), and BKCa channels in vascular myocytes (23, 31, 50). In regard to the latter effect of NFA on BKCa channels, Sun et al. (58) showed that the vasorelaxation of PA from CH rats precontracted with 5-HT was unaffected by the BKCa channel inhibitor. One study also reported the inhibition of a nonselective cation current in rat exocrine pancreatic cells (22). Another potential confounding action of NFA relates to its anti-inflammatory property (fenemates were first developed as a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs to treat pain associated with arthritis) that could indirectly influence ion channels and vascular tone by altering the release of vasoactive byproducts of arachidonic metabolism (e.g., prostaglandins) by the COX pathways. Our data suggest that such a possibility was unlikely as 30 or 100 μM NFA was equally effective in producing vasorelaxation of conduit pulmonary arteries from both study groups in the presence of the COX inhibitor indomethacin. It is possible that the greater relaxation mediated by NFA over nifedipine in conduit PA from MCT rats is real and involved an interaction of ClCa with additional voltage-independent Ca2+ entry pathways such a receptor- and store-operated Ca2+ entry (2, 20, 65). However, it is also plausible that NFA altered pulmonary arterial tone by mediating nonspecific inhibitory effects on the Rho kinase pathway, which can promote smooth muscle force by increasing Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus, especially in PH elicited by CH (8).

As an alternative approach, complementary experiments with the new specific ClCa/TMEM16A inhibitor T16AInh-A01 produced quantitatively similar effects to those produced by 100 μM NFA. The compound abrogated the enhanced contraction to 5-HT observed in conduit and intralobar PA of MCT-treated rats down to the level observed with pulmonary arteries from control animals. This compound was shown to inhibit ICl(Ca) in FRT cells transfected with TMEM16A with an IC50 of ∼ 1 μM (48), and to potently block macroscopic and unitary ICl(Ca) in rabbit PA myocytes (15). At the concentration used in our study, the blocker produced no effect on the contraction of mouse thoracic aorta evoked by 60 mM KCl and the vasorelaxation to agonists caused by T16AInh-A01 was unaffected by the addition of a cocktail of K+ channel antagonists (15). Taken together our results with NFA and T16AInh-A01 are very similar to those obtained with the CH model of pulmonary hypertension in the same species (58).

In conclusion, our findings indicate that in addition to alterations in the activity and expression of voltage-dependent K+ (70) and Ca2+ channels (29), TRPC (43, 68), and CLC-3 channels (13), a Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance was shown to be significantly elevated in smooth muscle cells of conduit and small resistance pulmonary arteries from a widely used animal model of PH, an observation that was also recently made in the CH model of PH (58). This increase was paralleled by a similar enhancement of expression of TMEM16A at the mRNA and protein levels. The study suggests that this ionic mechanism will now have to be considered when devising new therapeutic approaches in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension in humans.

The involvement of various classes of Cl− channels in cell volume regulation, apoptosis, cell cycle and cancerous growth is well documented (38). Cl− channels have been implicated in the proliferation of PASMCs, with swelling-regulated currents and CLC-3 being significantly increased in proliferating cells compared with nonproliferating cells and PA from MCT-treated rats (13, 42). Whether the expression and function of Bestrophin genes, another family of genes encoding for voltage- and time-independent Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (26), which are expressed in vascular myocytes (41), also participate in the structural and functional remodeling of the pulmonary arterial vasculature in pulmonary hypertension still remains to be determined. Interestingly, analysis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumors has shown an upregulation of TMEM16A mRNA and protein in neoplastic cells (12) and other forms of cancer (27). Therefore, it is possible that up regulated ClCa/TMEM16A channels may serve a dual role in PH, facilitating membrane depolarization and vasoconstriction, and participating in remodeling of the arterial wall by a yet undefined mechanism. A potentially important role of TMEM16A on cell proliferation in PH is supported by a recent study demonstrating that downregulation of this protein is a major contributing factor in the remodeling of the wall of cerebral arteries in the two-kidney, two clip hypertensive rat model (62). Investigation of these two hypothetical roles of this class of anion channels will require the generation of sophisticated transgenic animal models and approaches as global TMEM16A knockout mice die prematurely after birth due to defective development of the airways (53) It will be essential in the near future to determine whether TMEM16A/ClCa channels are also upregulated and play a role in human pulmonary hypertension. Table 1

Table 1.

primer sequences for primers designed to either span, or anneal to, putative alternative splicing sites within the TMEM16A gene sequence

| Gene | Primer Sequence [(+)sense, (−)antisense] | GenBank Accession No. | Amplicon, bp | Region Spanned |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon a annealing | (+)5′-GGCACAGGACGCAGGAACCC-3′ | NM_001107564 | 173 | 155–328 |

| (−)5′-CCCTCGGACGGCAGGTAGCCC-3′ | ||||

| Exon b spanning | (+)5′-CCCATCCAGCCCAAGGTGGC-3′ | NM_001107564 | 656 | 834–1,490 |

| (−)5′-GGCACGCGCTGTGGCACAGGC-3′ | ||||

| Exon b annealing | (+)5′-GGGAAGAAGGAAGGACTCTGCC-3′ | NM_001107564 | 456 | 1,034–1,490 |

| (−)5′-GGCACGCGCTGTGGCACAGGC-3′ | ||||

| Exon c annealing | (+)5′-GGAGGAGGAGGAAGCTGTCAAG-3′ | NM_001107564 | 421 | 2,265–2,686 |

| (−)5′-GGCCTTGAAGGTTAGCCTCTCC-3′ | ||||

| Exon c spanning | (+)5′-GCCTGTACTTTGCCTGGCTTGG-3′ | NM_001107564 | 380 | 1,921–2,301 |

| (−)5′-GGCTTCATACTCTGCTCTGGG-3′ | ||||

| Exon c spanning | (+)5′-GCCTGTGCCACAGCCCGTGCC-3′ | NM_001107564 | 188 | 2,113–2,301 |

| (−)5′-GGCTTCATACTCTGCTCTGGG-3′ | ||||

| Exon d spanning | (+)5′-GCCTGTGCCACAGCGCGTGCC-3′ | NM_001107564 | 561 | 2,113–2,673 |

| (−)5′-GGCCTTGAAGGTTAGCCTCTCC-3′ | ||||

| Exon d annealing | (+)5′-CCGATTCCCAGCCTATTTCACC-3′ | NM_001107564 | 298 | 375–2,673 |

| (−)5′-GGCCTTGAAGGTTAGCCTCTCC-3′ |

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants 5-R01-HL-075477 and 3-R01-HL-075477-04S1 (to N. Leblanc) and British Heart Foundation Grant PG/05/038 (to I. A. Greenwood). The publication was also made possible by National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) Grant 5-P20-RR-15581 (to N. Leblanc), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) supporting two Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. The publication was also made possible by NCRR Grant P20-RR-016464 from the INBRE Program. R. J. Ayon was supported by a Ruth Kirschstein Predoctoral Research Fellowship from NIH (5-F31-HL-090023). The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.S.F., A.J.D., C.A.S., M.L.V., I.A.G., and N.L. conception and design of research; A.S.F., T.C.J., M.L.H., R.J.A., M.W., J.J., N.F., L.Y., D.D.D., C.A.S., M.L.V., I.A.G., and N.L. performed experiments; A.S.F., T.C.J., M.L.H., R.J.A., M.W., J.J., N.F., A.J.D., L.Y., D.D.D., C.A.S., M.L.V., I.A.G., and N.L. analyzed data; A.S.F., R.J.A., M.W., A.J.D., D.D.D., C.A.S., M.L.V., I.A.G., and N.L. interpreted results of experiments; A.S.F. and N.L. prepared figures; A.S.F. drafted manuscript; A.S.F., R.J.A., A.J.D., C.A.S., M.L.V., I.A.G., and N.L. edited and revised manuscript; A.S.F., R.J.A., J.J., N.F., A.J.D., L.Y., D.D.D., C.A.S., M.L.V., I.A.G., and N.L. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altiere RJ, Olson JW, Gillespie MN. Altered pulmonary vascular smooth muscle responsiveness in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 236: 390–395, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angermann JE, Forrest AS, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels by store-operated Ca2+ entry in arterial smooth muscle cells does not require reverse-mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 90: 903–921, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Angermann JE, Sanguinetti AR, Kenyon JL, Leblanc N, Greenwood IA. Mechanism of the inhibition of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents by phosphorylation in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Gen Physiol 128: 73–87, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Archer SL, Weir EK, Wilkins MR. Basic science of pulmonary arterial hypertension for clinicians: new concepts and experimental therapies. Circulation 121: 2045–2066, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ayon R, Sones W, Forrest AS, Wiwchar M, Valencik ML, Sanguinetti AR, Perrino BA, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Complex phosphatase regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 284: 32507–32521, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bogaard HJ, Abe K, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Voelkel NF. The right ventricle under pressure: cellular and molecular mechanisms of right-heart failure in pulmonary hypertension. Chest 135: 794–804, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonnet P, Bonnet S, Boissiere J, Le Net JL, Gautier M, Dumas de la Roque E, Eder V. Chronic hypoxia induces nonreversible right ventricle dysfunction and dysplasia in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1023–H1028, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Broughton BR, Jernigan NL, Norton CE, Walker BR, Resta TC. Chronic hypoxia augments depolarization-induced Ca2+ sensitization in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle through superoxide-dependent stimulation of RhoA. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L232–L242, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Busch AE, Herzer T, Wagner CA, Schmidt F, Raber G, Waldegger S, Lang F. Positive regulation by chloride channel blockers of IsK channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Pharmacol 46: 750–753, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campian ME, Hardziyenka M, Michel MC, Tan HL. How valid are animal models to evaluate treatments for pulmonary hypertension? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 373: 391–400, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 322: 590–594, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carles A, Millon R, Cromer A, Ganguli G, Lemaire F, Young J, Wasylyk C, Muller D, Schultz I, Rabouel Y, Dembele D, Zhao C, Marchal P, Ducray C, Bracco L, Abecassis J, Poch O, Wasylyk B. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma transcriptome analysis by comprehensive validated differential display. Oncogene 25: 1821–1831, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dai YP, Bongalon S, Hatton WJ, Hume JR, Yamboliev IA. ClC-3 chloride channel is upregulated by hypertrophy and inflammation in rat and canine pulmonary artery. Br J Pharmacol 145: 5–14, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis AJ, Forrest AS, Jepps TA, Valencik ML, Wiwchar M, Singer CA, Sones WR, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Expression profile and protein translation of TMEM16A in murine smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C948–C959, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis AJ, Shi J, Pritchard HA, Chadha PS, Leblanc N, Vasilikostas G, Yao Z, Verkman AS, Albert AP, Greenwood IA. Potent vasorelaxant activity of the TMEM16A inhibitor T16Ainh-A01. Br J Pharmacol 2012. September 5 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De La Fuente R, Namkung W, Mills A, Verkman AS. Small-molecule screen identifies inhibitors of a human intestinal calcium-activated chloride channel. Mol Pharmacol 73: 758–768, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farrugia G, Rae JL, Szurszewski JH. Characterization of an outward potassium current in canine jejunal circular smooth muscle and its activation by fenamates. J Physiol 468: 297–310, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrera L, Caputo A, Ubby I, Bussani E, Zegarra-Moran O, Ravazzolo R, Pagani F, Galietta LJ. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem 284: 33360–33368, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrera L, Scudieri P, Sondo E, Caputo A, Caci E, Zegarra-Moran O, Ravazzolo R, Galietta LJ. A minimal isoform of the TMEM16A protein associated with chloride channel activity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818: 2214–2223, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Forrest AS, Angermann JE, Raghunathan R, Lachendro C, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Intricate interaction between store-operated calcium entry and calcium-activated chloride channels in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 661: 31–55, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gillespie MN, Olson JW, Reinsel CN, O'Connor WN, Altiere RJ. Vascular hyperresponsiveness in perfused lungs from monocrotaline-treated rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 251: H109–H114, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gogelein H, Dahlem D, Englert HC, Lang HJ. Flufenamic acid, mefenamic acid and niflumic acid inhibit single nonselective cation channels in the rat exocrine pancreas. FEBS Lett 268: 79–82, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenwood IA, Large WA. Comparison of the effects of fenamates on Ca-activated chloride and potassium currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 116: 2939–2948, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Leblanc N. Differential regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Physiol 534: 395–408, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Sanguinetti A, Perrino BA, Leblanc N. Calcineurin Aα but not Aβ augments ICl(Ca) in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 279: 38830–38837, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hartzell HC, Qu Z, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol Rev 88: 639–672, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartzell HC, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT, Qu Z. Anoctamin/TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Physiol 587: 2127–2139, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayashi Y, Lalich JJ. Renal and pulmonary alterations induced in rats by a single injection of monocrotaline. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 124: 392–396, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirenallur SD, Haworth ST, Leming JT, Chang J, Hernandez G, Gordon JB, Rusch NJ. Upregulation of vascular calcium channels in neonatal piglets with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L915–L924, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hislop A, Reid L. Arterial changes in Crotalaria spectabilis-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Br J Exp Pathol 55: 153–163, 1974 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hogg RC, Wang Q, Large WA. Action of niflumic acid on evoked and spontaneous calcium-activated chloride and potassium currents in smooth muscle cells from rabbit portal vein. Br J Pharmacol 112: 977–984, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huxtable R, Ciaramitaro D, Eisenstein D. The effect of a pyrrolizidine alkaloid, monocrotaline, and a pyrrole, dehydroretronecine, on the biochemical functions of the pulmonary endothelium. Mol Pharmacol 14: 1189–1203, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jasmin JF, Cernacek P, Dupuis J. Activation of the right ventricular endothelin (ET) system in the monocrotaline model of pulmonary hypertension: response to chronic ETA receptor blockade. Clin Sci (Lond) 105: 647–653, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jasmin JF, Mercier I, Dupuis J, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP. Short-term administration of a cell-permeable caveolin-1 peptide prevents the development of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 114: 912–920, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones JE, Mendes L, Rudd MA, Russo G, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. Serial noninvasive assessment of progressive pulmonary hypertension in a rat model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H364–H371, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Keane PM, Kay JM, Suyama KL, Gauthier D, Andrew K. Lung angiotensin converting enzyme activity in rats with pulmonary hypertension. Thorax 37: 198–204, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kitamura K, Yamazaki J. Chloride channels and their functional roles in smooth muscle tone in the vasculature. Jap J Pharmacol 85: 351–357, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kunzelmann K. Ion channels and cancer. J Membr Biol 205: 159–173, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lalich JL, Johnson WD, Raczniak TJ, Shumaker RC. Fibrin thrombosis in monocrotaline pyrrole-induced cor pulmonale in rats. Arch Pathol Lab Med 101: 69–73, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C435–C454, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leblanc N, Ledoux J, Saleh S, Sanguinetti A, Angermann J, O'Driscoll K, Britton F, Perrino BA, Greenwood IA. Regulation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle cells: a complex picture is emerging. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 83: 541–556, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liang W, Ray JB, He JZ, Backx PH, Ward ME. Regulation of proliferation and membrane potential by chloride currents in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 54: 286–293, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin MJ, Leung GP, Zhang WM, Yang XR, Yip KP, Tse CM, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of store-operated and receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells: a novel mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res 95: 496–505, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]