Abstract

We adapted high-resolution melting (HRM) technology to measure genetic diversity without sequencing. Diversity is measured as a single numeric HRM score. Herein, we determined the impact of mutation types and amplicon characteristics on HRM diversity scores. Plasmids were generated with single-base changes, insertions, and deletions. Different primer sets were used to vary the position of mutations within amplicons. Plasmids and plasmid mixtures were analyzed to determine the impact of mutation type, position, and concentration on HRM scores. The impact of amplicon length and G/C content on HRM scores was also evaluated. Different mutation types affected HRM scores to varying degrees (1-bp deletion < 1-bp change < 3-bp insertion < 9-bp insertion). The impact of mutations on HRM scores was influenced by amplicon length and the position of the mutation within the amplicon. Mutations were detected at concentrations of 5% to 95%, with the greatest impact at 50%. The G/C content altered melting temperature values of amplicons but had no impact on HRM scores. These data are relevant to the design of assays that measure genetic diversity using HRM technology.

High-resolution melting (HRM) technology has been widely used to detect specific mutations in DNA.1,2 Mutations and polymorphisms in DNA amplicons affect the melting profile of DNA duplexes.3 In HRM assays, DNA melting is observed as a sample is warmed over a range of temperatures; duplex melting is visualized as declining fluorescence due to the release of a saturating duplex-dependent fluorescent dye.2 In HRM assays, mutation detection usually relies on changes in the temperature at which the peak melting rate is achieved (Tm) or on other features of melting curve shape.4 Assays based on HRM of DNA duplexes have been developed to detect mutations associated with cancer5 and genetic disease.6 HRM technology is also being developed for analysis of specific mutations in bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens7 that might harbor resistance mutations8 or mutations conferring virulence.9

We developed a rapid assay for measuring nucleic acid diversity that is based on HRM technology.10 This assay is based on the premise that the magnitude of the temperature range required to melt a particular DNA pool increases with the diversity of molecules in that pool. In the HRM diversity assay, the level of genetic diversity in a pool of DNA amplicons is reported as a single numeric HRM score. This assay has been successfully used to quantify genetic diversity in plasma samples from HIV-infected individuals.10–12 The results of the assay are highly reproducible10,13 and are significantly associated with sequence-based diversity measures.12

HIV diversity may have important clinical, demographic, or subtype-specific correlates. Historically, analysis of HIV diversity has required costly and time-consuming sequencing analysis of individual HIV variants (eg, using cloning, single-genome sequencing, or next-generation sequencing). Although next-generation sequencing is a powerful tool for evaluating HIV diversity, the methods are expensive and require specialized equipment and complex data-handling protocols.14,15 The HRM diversity assay offers a simple, less expensive, and scalable method for quantifying HIV diversity. HRM scores are associated with HIV disease stage in adults, suggesting that the HRM diversity assay may be useful for cross-sectional analysis of HIV incidence.11 In pediatric populations, the HRM diversity assay has revealed associations between HIV diversity and duration of HIV infection,13,16 infant survival,13 and response to antiretroviral therapy.16 The HRM diversity assay has also been used to document bottlenecking of viral populations in children exposed to nonsuppressive antiretroviral therapy.16

Previous studies have evaluated the impact of amplicon characteristics and mutation types on Tm. Herein, we characterized the impact of mutation type, amplicon size, mutation location within the amplicon, concentration of mutant DNA in a DNA mixture, and G/C content on HRM score. These data provide a foundation for understanding the output of the HRM diversity assay for analysis of HIV and for other applications.

Materials and Methods

Generation of HIV Plasmids

Three regions of the HIV genome, each approximately 1000 bp, were ligated into the EcoRV site of vector pUC57, and plasmids were propagated in the Escherichia coli strain DH5α. These regions correspond to the following nucleotide positions in HXB2 (accession number K03455): GAG, 1117 to 2106; POL, 4353 to 5342; and ENV, 7425 to 8411. The plasmid inserts [wild type (WT)] were then subjected to site-directed mutagenesis to generate a series of mutant plasmids with single-base change mutations. These mutations were introduced at the following nucleotide positions in the HXB2 sequences: GAG, 1614; POL, 4847; and ENV, 7916. Additional plasmids were generated by introducing a single-base deletion, a 3-bp insertion, or a 9-bp insertion at the same nucleotide positions. The sequence of each plasmid insert was verified by sequencing (Supplemental Table S1). WT plasmid inserts each matched the relevant region of GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank; accession number K03455). GenBank accession numbers for mutagenized plasmids are as follows: GAG, JX472242 to JX472247; POL, JX472248 to JX472253; and ENV, JX472254 to JX472259. Plasmids were diluted to a concentration of 5 ng/μL, and artificial diverse populations were generated from the diluted plasmid preparations. WT and mutant plasmids were mixed at the following ratios (WT:mutant): 0:100, 1:99, 5:95, 10:90, 25:75, 50:50, 75:25, 90:10, 95:5, 99:1, and 100:0, yielding populations that were 0%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 95%, 99%, and 100% WT, respectively. These plasmids and plasmid mixtures were analyzed using the HRM diversity assay, as described later.

Clade B Clones

A panel of 11 clade B molecular clones was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Pathogenesis and Basic Research Branch, Division of AIDS NIAID). This panel included transmitted/founder HIV-1 infectious molecular clones,17–20 HXB2-gpt,21 and HXB2-env.21 These plasmids were diluted to approximately 5 ng/μL and analyzed with the HRM diversity assay, as described later.

Design of Primers Used in the HRM Diversity Assay

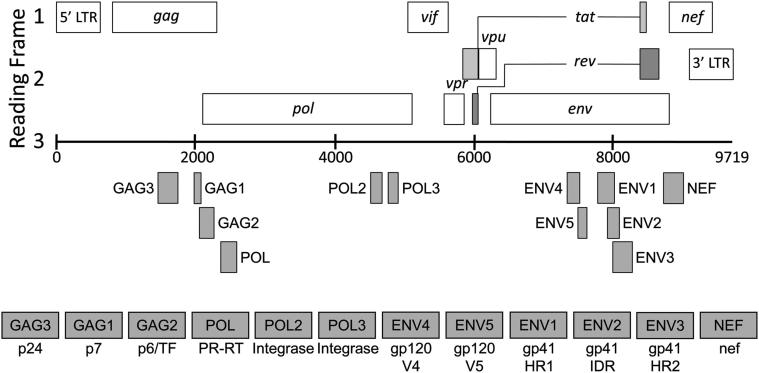

HRM primers (n = 42) were designed to anneal to each set of plasmids (Supplemental Table S1) at approximately the same distances (25, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300, and 400 bp) upstream and downstream of the mutation site (Tables 1–3). These primers were used to generate amplicons that varied in size and in the position of the mutation within the amplicon. Additional HRM primers (n = 24) were designed to amplify 12 different regions of the HIV genome using infectious molecular clones as templates; these regions were selected based on variable G/C content (Table 4 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Description of Primers Used to Amplify GAG Plasmids

| Primer name∗ | Primer sequence | Location in HXB2 |

|---|---|---|

| GAG_closeF | 5′-GGATAATCCTGGGATTAAATAAAATAGTAAG-3′ | 1583–1613 |

| GAG_450F | 5′-ATCCACCTATCCCAGTAGGAGAAATTTAT-3′ | 1547–1575 |

| GAG_400F | 5′-CTTCAGGAACAAATAGGATGGATGACA-3′ | 1516–1542 |

| GAG_350F | 5′-GCCAGATGAGAGAACCAAGGGGAAG-3′ | 1466–1490 |

| GAG_300F | 5′-TGCAGAATGGGATAGAGTGCATCC-3′ | 1416–1439 |

| GAG_200F | 5′-CAGAAGGAGCCACCCCACAAGATTTA-3′ | 1316–1341 |

| GAG_100F | 5′-GGGGCAAATGGTACATCAGGCCATA-3′ | 1206–1230 |

| GAG_closeR | 5′-CCAGAATGCTGGTAGGGCTATACA-3′ | 1639–1616 |

| GAG_550R | 5′-AAGGGTTCCTTTGGTCCTTGTCT-3′ | 1667–1645 |

| GAG_600R | 5′-AGCTTGCTCGGCTCTTAGAGTTTT-3′ | 1716–1693 |

| GAG_650R | 5′-TCTGGGTTCGCATTTTGGACCA-3′ | 1775–1754 |

| GAG_700R | 5′-GTGTAGCCGCTGGTCCCAATGCT-3′ | 1816–1794 |

| GAG_800R | 5′-TGTTACTTGGCTCATTGCTTCAGC-3′ | 1902–1879 |

| GAG_900R | 5′-CCTAGGGGCCCTGCAATTTCTG-3′ | 2016–1995 |

The number immediately following the underline indicates the approximate location of the primer relative to the 5′ end of the insert. The letter following the number denotes whether the primer was forward (F) or reverse (R). The word close indicates that the primer was as close to the mutation site as possible while still allowing amplification to occur.

Table 2.

Description of Primers Used to Amplify POL Plasmids

| Primer name∗ | Primer sequence | Location in HXB2 |

|---|---|---|

| POL_closeF | 5′-GGAAAGAATAGTAGACATAATAGCAAC-3′ | 4820–4846 |

| POL_450F | 5′-ACAGTGCAGGGGAAAGAATAGTAGA-3′ | 4810–4834 |

| POL_400F | 5′-ACAGCAGTACAAATGGCAGTATTCA-3′ | 4749–4773 |

| POL_350F | 5′-TAGGACAGGTAAGAGATCAGGCTGA-3′ | 4714–4738 |

| POL_300F | 5′-TCCCTACAATCCCCAAAGTCAAGG-3′ | 4652–4675 |

| POL_200F | 5′-ACAATACATACTGACAATGGCAGCA-3′ | 4563–4587 |

| POL_100F | 5′-GTAGCAGTTCATGTAGCCAGTGGAT-3′ | 4452–4476 |

| POL_closeR | 5′-AATTTGTTTTTGTAATTCTTTAGTTTGTATGTC-3′ | 4880–4848 |

| POL_550R | 5′-TGCTGTCCCTGTAATAAACCCGAA-3′ | 4920–4897 |

| POL_600R | 5′-GAGCTTTGCTGGTCCTTTCCAA-3′ | 4952–4931 |

| POL_650R | 5′-TGTCACTATTATCTTGTATTACTACTGC-3′ | 4998–4971 |

| POL_700R | 5′-CATCACCTGCCATCTGTTTTCCA-3′ | 5064–5042 |

| POL_800R | 5′-ATCCCCTAGCTTTCCCTGAAACAT-3′ | 5152–5129 |

| POL_900R | 5′-TCCTGTATGCAGACCCCAATATGT-3′ | 5265–5242 |

The number immediately following the underline indicates the approximate location of the primer relative to the 5′ end of the insert. The letter following the number denotes whether the primer was forward (F) or reverse (R). The word close indicates that the primer was as close to the mutation site as possible while still allowing amplification to occur.

Table 3.

Description of Primers Used to Amplify ENV Plasmids

| Primer name∗ | Primer sequence | Location in HXB2 |

|---|---|---|

| ENV_closeF | 5′-ATTTGCTGAGGGCTATTGAGGCGC-3′ | 7885–7908 |

| ENV_450F | 5′-AGCAGAACAATTTGCTGAGGGCTA-3′ | 7876–7899 |

| ENV_400F | 5′-TGACGCTGACGGTACAGGCC-3′ | 7828–7847 |

| ENV_350F | 5′-TTCCTTGGGTTCTTGGGAGCAG-3′ | 7779–7800 |

| ENV_300F | 5′-AGGCAAAGAGAAGAGTGGTGCAG-3′ | 7723–7745 |

| ENV_200F | 5′-TCCGAGATCTTCAGACCTGGAGGA-3′ | 7617–7640 |

| ENV_100F | 5′-AATGTATGCCCCTCCCATCAGTGGA-3′ | 7523–7547 |

| ENV_closeR | 5′-TTGATGCCCCAGACTGTGAGTTGCA-3′ | 7945–7921 |

| ENV_550R | 5′-ATCTTTCCACAGCCAGGATTCTTGC-3′ | 7980–7956 |

| ENV_600R | 5′-CCAGAGCAACCCCAAATCCCCAGG-3′ | 8023–8000 |

| ENV_650R | 5′-ACTCCAACTAGCATTCCAAGGCA-3′ | 8069–8047 |

| ENV_700R | 5′-TGTCCCACTCCATCCAGGTCGTGT-3′ | 8121–8098 |

| ENV_800R | 5′-AACCAATTCCACAAACTTGCCCATT-3′ | 8242–8218 |

| ENV_900R | 5′-AACGATAATGGTGAATATCCCTGC-3′ | 8374–8351 |

The number immediately following the underscore indicates the approximate location of the primer relative to the 5′ end of the insert. The letter following the number denotes whether the primer was forward (F) or reverse (R). The word close indicates that the primer was as close to the mutation site as possible while still allowing amplification to occur.

Table 4.

Regions of the HIV Genome Analyzed Using the HRM Diversity Assay

| Region analyzed∗ | Corresponding region in HXB2∗ | Sequences of primers used to produce amplicons for HRM diversity analysis† | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAG1 (p7) | 1998–2097 | Forward: 5′-AAATTGCAGGGCCCCTAGGAA-3′ | 100 |

| Reverse: 5′-TTTCCCTAAAAAATTAGCCTGTCT-3′ | |||

| GAG2 (p6/TF) | 2068–2278 | Forward: 5′-ACTGAGAGACAGGCTAATTTTTTAG-3′ | 211 |

| Reverse: 5′-GGTCGTTGCCAAAGAGTGATTTG-3′ | |||

| GAG3 (p24) | 1471–1761 | Forward: 5′-ATGAGAGAACCAAGGGGAAGTGA-3′ | 291 |

| Reverse: 5′-TTGGACCAACAAGGTTTCTGTCATCCA-3′ | |||

| POL (PR/RT) | 2373–2597 | Forward: 5′-AAATGGAAACCAAAAATGATAG-3′ | 225 |

| Reverse: 5′-CATTCCTGGCTTTAATTTTACTG-3′ | |||

| POL2 (integrase) | 4535–4695 | Forward: 5′-AAAATTAGCAGGAAGATGGCCAG-3′ | 161 |

| Reverse: 5′-TATTCATAGATTCTACTACTCCTTG-3′ | |||

| POL3 (integrase) | 4784–4922 | Forward: 5′-TAAAAGAAAAGGGGGGATTGG-3′ | 139 |

| Reverse: 5′-TCTGCTGTCCCTGTAATAAACC-3′ | |||

| ENV1 (gp41 HR1) | 7798–8036 | Forward: 5′-CAGCAGGWAGCACKATGGG-3′ | 239 |

| Reverse: 5′-GCARATGWGYTTTCCAGAGCADCC-3′ | |||

| ENV2 (gp41 IDR) | 7950–8119 | Forward: 5′-CTYCAGRCAAGARTCYTGGC-3′ | 170 |

| Reverse: 5′-TCCCAYTSCAKCCARGTC-3′ | |||

| ENV3 (gp41 HR2) | 8016–8299 | Forward: 5′-TGCTCTGGAAARCWCATYTGC-3′ | 284 |

| Reverse: 5′-AARCCTCCTACTATCATTATRA-3′ | |||

| ENV4 (gp120 V4) | 7358–7540 | Forward: 5′-TRGAGGRGAATTYTTCTAYTG-3′ | 183 |

| Reverse: 5′-ATRGGAGGGGCATAYATTGC-3′ | |||

| ENV5 (gp120 V5) | 7521–7654 | Forward: 5′-GCAATRTATGCCCCTCC-3′ | 134 |

| Reverse: 5′-TCYYTCATATYTCCTC-3′ | |||

| NEF1 (nef) | 8749–9038 | Forward: 5′-ACATACCTAGAAGAATAAGACAGGG-3′ | 290 |

| Reverse: 5′-TAAGTCATTGGTCTTAAAGGTACCTG-3′ |

HR, heptad repeat; IDR, immunodominant region; PR, protease; RT, reverse transcriptase; TF, transframe.

See Figure 1.

Mixed nucleotides were present at some positions, as follows: W, A/T; K, G/T; R, A/G; Y, C/T; D, A/G/T; S, G/C.

Figure 1.

Regions of the HIV genome analyzed using the HRM diversity assay. The relevant regions of the HIV genome are shown. Numbers at the ends of each genomic segment correspond to coordinates in HXB2 (GenBank accession number K03455). The amplicons used for HRM diversity analysis (regions analyzed) are indicated by shaded boxes. A: Gag amplicons: The GAG3 amplicon contains a portion of the coding region of gag p24. The GAG1 amplicon includes a portion of the coding regions for gag p7 and gag p1. The GAG2 amplicon includes the coding regions for gag p1 and gag p6 and extends into the coding region for HIV protease; this amplicon also corresponds to the transframe protein. B: Pol amplicons: The POL amplicon spans the junction between the coding regions of HIV protease and HIV reverse transcriptase. The POL2 and POL3 amplicons each include a portion of the region that codes the integrase enzyme. C: Env amplicons: The ENV4 and ENV5 amplicons each encompass the V4 and V5 hypervariable loop regions of gp120, respectively. The ENV1 amplicon includes the coding region for heptad repeat 1 (HR1) of gp41 and portions of the coding regions to either side of HR1. The ENV2 amplicon includes the coding region for immunodominant region (IDR) cluster I of gp41 and portions of the coding regions for HR1 and HR2.24 The ENV3 amplicon includes the coding region for heptad repeat 2 (HR2) and portions of the coding regions to either side of HR2. D: Nef amplicon: The NEF amplicon includes a portion of the region that codes the nef accessory protein.

Figure adapted from Kuiken et al (Eds.).23

Analysis of Plasmids and Plasmid Mixtures with the HRM Diversity Assay

Regions of the HIV genome were amplified using plasmids as templates in the presence of LCGreen Plus dye (Idaho Technology Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) (Tables 1–4 and Figure 1). PCRs (10 μL) included the following components: 4.6 μL of H2O, 4 μL of Idaho Technology Mastermix (Idaho Technology Inc.), 0.2 μL each of 10 μmol/L forward and reverse primer, and 1 μL (5 ng) of template DNA. Cycling conditions were as follows: a 2-minute hold at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds and 63°C for 30 seconds, followed by two sequential 30-second holds at 94°C and 28°C, and a terminal hold at 4°C. The resulting amplicons were melted using the LightScanner Instrument (model HR 96; Idaho Technology Inc.), and release of the dye was quantified as a function of temperature (melting range for amplicons derived from HIV gag and pol amplicons, 68°C to 98°C with a 65°C hold; melting range for amplicons derived from HIV env amplicons, 60°C to 98°C with a 57°C hold). Melting curves were used to determine HRM scores (the diversity output of the assay; melting peak width) using an automated software tool (DivMelt: HRM Diversity Assay Analysis Tool12,22) with the following settings: θ T1 = 50, θ T2 = 30, T1 hold interval = 0°C, T2 hold interval = 0°C, shoulder height threshold on, shoulder height threshold = 10%, exclude early peaks on (cutoff, 3°), T1 slope window = 1°C, and T2 slope window = 1°C (where T1 is the temperature where amplicon melting began and T2 is the temperature where amplicon melting was complete). Samples were analyzed in duplicate, and the results were averaged. If the difference in the duplicate HRM scores was >0.5, the data were rejected, and the samples were reanalyzed.

Statistical Analysis

The impact of mutations on HRM score was examined using analysis of variance; linear contrasts were used to compare the impact of different types of mutations. Scatterplots were used to display various mutation or amplicon characteristics on the x axis, and the variable Difference was displayed on the y axis. This variable represents the change in HRM score associated with each mutation (mutation impact). The difference was calculated as follows: i) the HRM score was determined for a plasmid mixture, ii) the HRM scores were calculated for pure WT and pure mutant DNA samples (each mixture component), iii) the weighted average (weighted by the relative concentrations of the mixture components) of the HRM scores of the pure plasmid components included in the mixture was then subtracted from the HRM score of the mixture to calculate the difference. This calculation produced expected measures that were used to compare HRM scores across the three different genomic regions. Simple linear regression was used to assess the relationships between G/C content and the temperature at which melting began (T1), the temperature at which melting ended (T2), the temperature of peak melting rate (Tm), and the HRM score. Analyses were performed using STATISTICA, Version 10 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK).

Results

The HRM diversity assay was used to analyze a series of pure plasmids and plasmid mixtures. In addition, a series of different primer sets was used to amplify different regions of the plasmids; by using this approach, it was possible to vary amplicon lengths and the positions of the mutations within the amplicons. These plasmids and amplification strategies were used to assess the impact of the following amplicon characteristics on HRM scores: i) mutation type (nucleotide substitutions and insertions/deletions), ii) amplicon length (ranging from 100 to 800 bp), iii) mutation location within the amplicon (near 5′, intermediate 5′, centered, intermediate 3′, and near 3′), iv) concentration of the mutant DNA (including 0%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 95%, 99%, or 100% mutant), and v) G/C content (ranging from 32% to 53%).

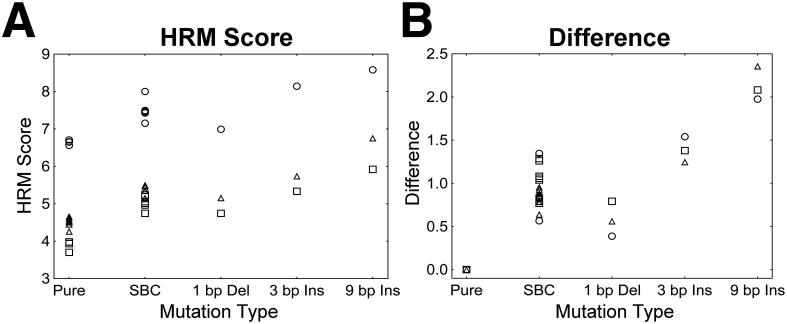

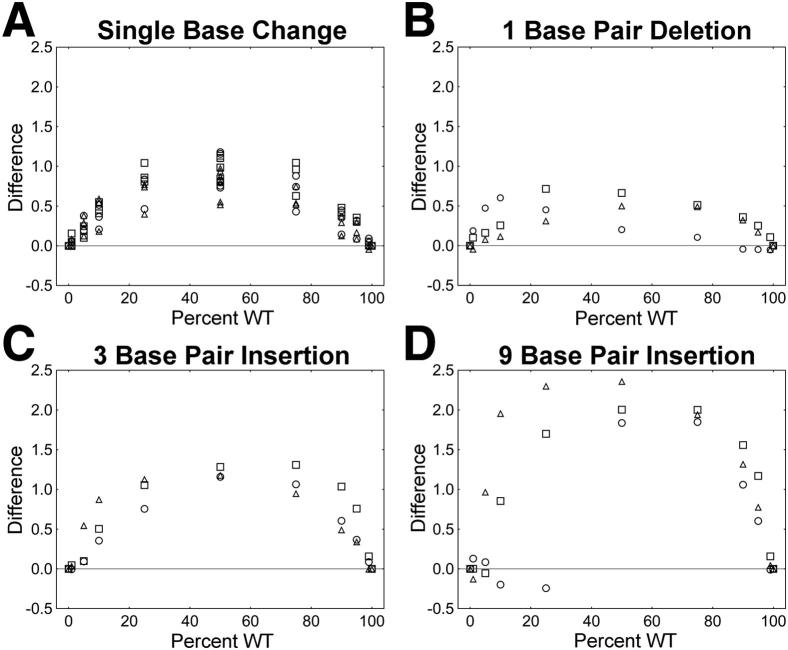

Mutation Type

HRM scores were significantly altered by the introduction of mutations into the amplicons, and the degree of the impact on HRM scores varied by mutation type (Figure 2). Each type of mutation evaluated had a notable effect on the HRM score when the mutations were introduced into the center of 100-bp amplicons (Figure 2A). Because HRM score could be influenced by the sequence surrounding a mutation, there was significant region-specific variation in HRM scores. Data from each region were normalized to simplify comparisons of the impacts of different mutations on HRM score across the three regions analyzed (see Materials and Methods). The resulting value, termed difference, was used as a measure of the impact of mutations on HRM scores (Figure 2B). We found that the impact of 1-bp deletions on HRM score was less than the impact of single-base changes (P = 0.0006). In contrast, the impact of 3-bp insertions was greater than the impact of single-base changes (P < 0.0001), and the impact of 9-bp insertions was greater than the impact of 3-bp insertions (P < 0.0001). The mean HRM score differences between DNA mixtures and pure DNA populations were as follows: 0.93, 0.58, 1.39, and 2.14 for single-base changes, 1-bp deletions, 3-bp insertions, and 9-bp insertions, respectively.

Figure 2.

The impact of mutation type on the ability to detect a mutation in a mixed population, including WT and mutant amplicons. Pure plasmid populations (Pure; n = 21; consisting of each WT, single-base mutant plasmid, and insertion/deletion mutant plasmid from each of the three regions as pure populations) and plasmid mixtures containing single-base changes (SBC; n = 18), 1-bp deletions (1 bp Del; n = 3), 3-bp insertions (3 bp Ins; n = 3), and 9-bp insertions (9 bp Ins; n = 3) were evaluated. A: Different types of mutations had varied impacts on the HRM score. Region-specific differences in the sequence surrounding the mutations influenced HRM score. B: The impact of mutations on HRM scores was expressed as the difference between the HRM score for the mixed population and the weighted average of HRM scores for each plasmid in a mixture when the plasmids were assayed as pure populations (difference, see Materials and Methods). Circle, GAG; square, ENV; triangle, POL.

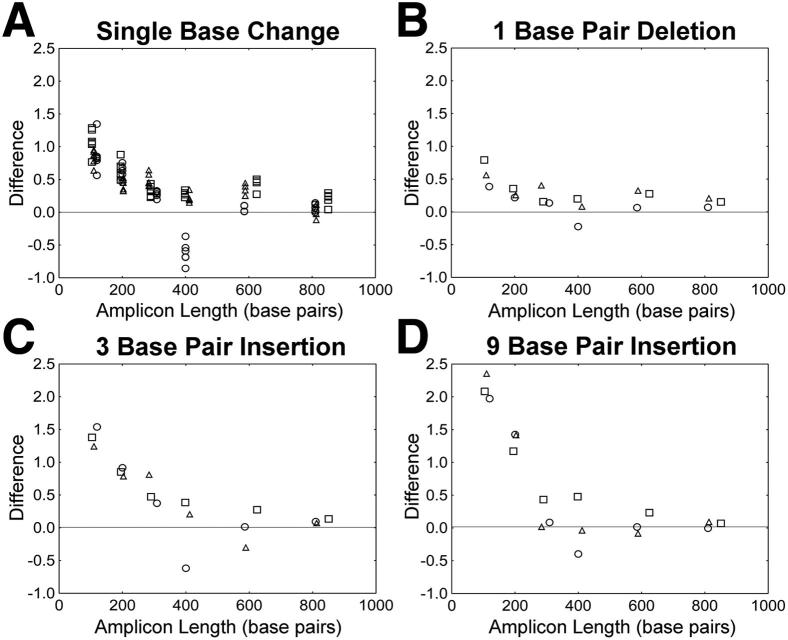

Amplicon Length

As the HRM amplicon length increased from 100 to 800 bp, the impact of mutations on HRM score declined (Figure 3). HRM scores were significantly affected when a single mutation was present at the center of a 100- to 300-bp amplicon at a concentration of 50%. In general, the impact of single mutations on HRM score declined with increasing amplicon length, and little change in HRM score was observed when amplicon length was increased beyond 300 bp.

Figure 3.

The impact of amplicon length on HRM score. The impact of amplicon length on difference in HRM score is shown for the following mutations: single-base changes (n = 18) (A), 1-bp deletions (n = 3) (B), 3-bp insertions (n = 3) (C), and 9-bp insertions (n = 3) (D). Circle, GAG; square, ENV; triangle, POL.

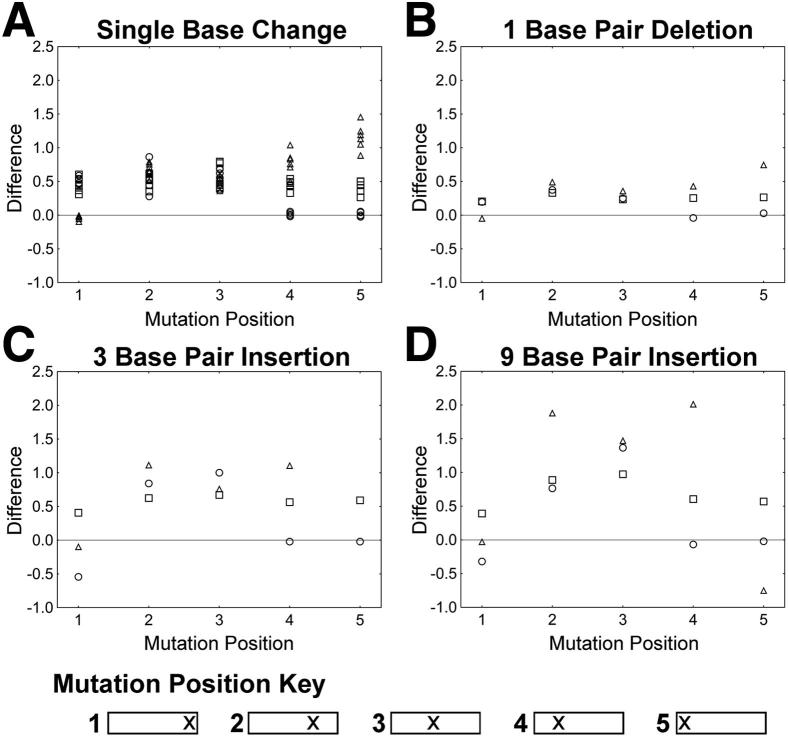

Mutation Location within the Amplicon

We analyzed the impact of mutation position on HRM score (Figure 4). In general, 1-bp deletions and single-base changes had similar effects on HRM score, regardless of their position within the amplicon (Figure 4, A and B). In contrast, both 3- and 9-bp insertions had the greatest impact on HRM score. The greatest impact on HRM score was observed when the mutations were located in the center of the amplicons (Figure 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

The impact of mutation location on HRM score. The impact of mutation location (the position of the mutation within the amplicon) on the ability to detect HRM score differences is shown for the following mutations: single-base changes (n = 18) (A), 1-bp deletions (n = 3) (B), 3-bp insertions (n = 3) (C), and 9-bp insertions (n = 3) (D). Circle, GAG; square, ENV; triangle, POL.

Mutation Concentration

For all of the mutation types evaluated, mutant concentration significantly affected HRM score (Figure 5). The impact of each mutation on HRM score increased as the proportion of mutant DNA approached 50%. However, notable differences between the HRM scores of pure DNA populations and DNA mixtures were still observed when the proportion of mutant DNA was only 5%.

Figure 5.

The impact of mutant plasmid concentration on HRM score. The impact of mutant plasmid concentration on the ability to detect HRM score differences is shown for the following mutations: single-base changes (n = 9) (A), 1-bp deletions (n = 3) (B), 3-bp insertions (n = 3) (C), and 9-bp insertions (n = 3) (D). Circle, GAG; square, ENV; triangle, POL.

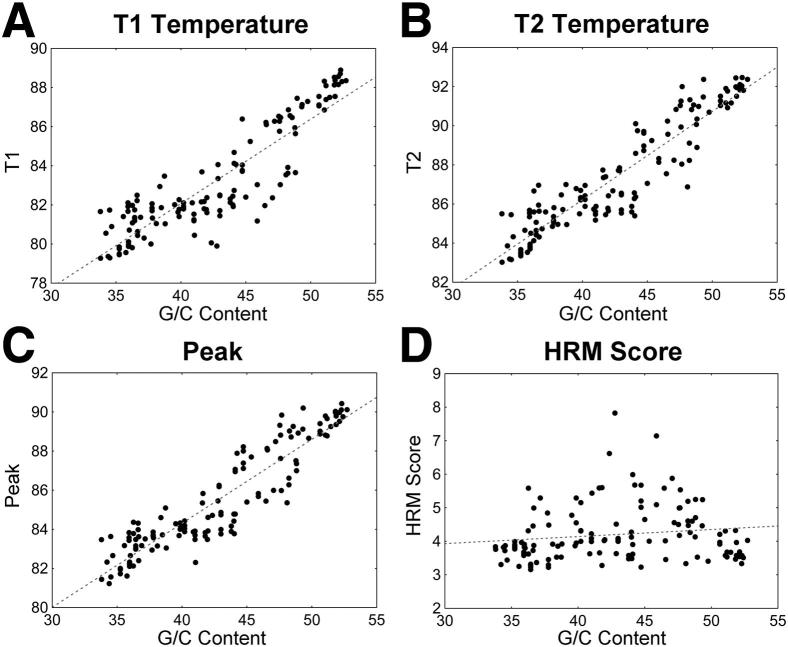

G/C Content

The impact of G/C content on HRM score was assessed using 11 clade B full-length molecular clones (see Materials and Methods, Figure 1, and Table 4). Primers were designed to amplify different regions of the HIV genome that had varied G/C content (Supplemental Table S2). The G/C content of the amplicon was strongly associated with the Tm of the melting curve (Figure 6). Specifically, G/C content was highly associated and highly correlated with T1 values (the temperature at which melting began, P < 0.0001, R2 = 0.7964) and with T2 values (the temperature at which melting ended, P < 0.0001, R2 = 0.8551). G/C content was also highly associated and correlated with the temperature corresponding to the peak melting rate, Tm (P < 0.0001, R2 = 0.8518). In contrast, HRM score (T2–T1) was not associated or correlated with G/C content (P = 0.0955, R2 = 0.0212).

Figure 6.

The impact of G/C content on duplex melting. The impacts of amplicon G/C content on duplex melting are shown: T1 (P < 0.0001; R2 = 0.7964, y = 64.8175 + 0.4313x) (A), T2 (P < 0.0001; R2 = 0.8551, y = 68.1143 + 0.4524x) (B), peak Tm (P < 0.0001; R2 = 0.8518, y = 67.1294 + 0.4295x) (C), and HRM score (P = 0.0955; R2 = 0.0212, y = 3.2968 + 0.0211x) (D). These values are obtained by analyzing 12 amplicons for each of the 11 plasmids. The HIV-derived plasmid inserts consist of nearly complete HIV genomes.

Discussion

The HRM diversity assay is a valuable tool for analyzing the genetic diversity of HIV. Because insertions, deletions, and single-base changes are all components of HIV diversity, it is important to understand the capacity of the HRM diversity assay to detect each of these mutation types. This report provides detailed information on the impacts of mutation and amplicon characteristics on HRM score. Different types of mutations had dramatically different effects on HRM score. The relative magnitudes of the HRM score differences were as follows: 1-bp insertion < single-base change < 3-bp insertion < 9-bp insertion. Amplicon length significantly affected the detection of mutations (Figure 3). When amplicon length exceeded 300 to 400 bp, it was less likely that a single mutation would result in an observable change in HRM score. In HIV, mutations are numerous, and the use of larger amplicons increases the likelihood of capturing diversity in the viral population. However, because large amplicons also decrease the ability of the HRM diversity assay to detect individual mutations, it may be desirable to avoid large amplicons. The introduction of mutations into longer amplicons is less likely to increase peak width because longer amplicons are more likely to contain two or more distinct melting domains. When there are two or more distinct melting domains, the impact of a single mutation may be less apparent. In this study, the 400-bp GAG amplicon displayed a unique decrease in HRM score when single-base mutations were introduced into the A/T-rich center of the amplicon. In this amplicon, melting may be initiated in this central A/T-rich region rather than at the ends of the amplicon. Introduction of mutations into the A/T-rich region in this relatively long amplicon may have reduced the HRM score because of the unusual melting pattern of this amplicon.

Varying the location of a mutation within an amplicon had little impact on HRM score when the mutation was a single-base change or a 1-bp deletion. In contrast, 3- or 9-bp insertions had the greatest impact when the insertion was centered within the amplicon (Figure 4); in some cases, centrally located mutations caused large increases in HRM score. Interestingly, these same insertions caused large decreases in HRM score when the mutations were near the ends of the amplicon. Mutations had the greatest impact on HRM score when they were present at a level of 50%. However, the HRM diversity assay detected many mutations at concentrations as low as 5%. Predictable relationships between G/C content and key melting temperature values (T1, T2, and Tm) were observed. Despite these relationships, we did not observe a significant impact of G/C content on HRM score.

One limitation of this study is that it was restricted to analysis of single mutations. In HIV-infected individuals, HIV usually exists as a swarm of genetically related variants. These variants can be highly heterogeneous. Amplicons derived from HIV typically contain many mutations. Although this report does not include analysis of the effect of complex combinations of mutations on HRM score, a recent study compared HRM scores from viral populations that were also analyzed by next-generation sequencing.12 In that study, the HRM scores were highly associated with sequence-based diversity measures that reflected variations in mutation type and number (genetic diversity, complexity, and Shannon entropy).12

In summary, this study provides valuable insights into many of the factors that affect DNA melting and diversity measures obtained using the HRM diversity assay. Although these experiments were performed using plasmids derived from the HIV genome, the results of this study should be relevant to the melting characteristics of other DNA populations.

Acknowledgments

The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH: Panel of Infectious Molecular Clones (catalog number 11919) from Dr. John Kappes; HIV-gpt (catalog number 1067) from Dr. Kathleen Page and Dr. Dan Littman; and pHXB2-env (catalog number 1069) from Dr. Kathleen Page and Dr. Dan Littman.

All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. In addition, M.M.C. conceived of the study, designed the study, coordinated the study, developed HRM diversity assay methods, generated and analyzed HRM data, and prepared the manuscript; D.D. advised data analyses for the project; and S.H.E. invented the HRM diversity assay, was the lead investigator responsible for the project, reviewed the data, and prepared the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by the HIV Prevention Trials Network, sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the National Institute of Mental Health; and grants from the Office of AIDS Research of the NIH and US Department of Health and Human Services (U01AI068613 and UM1AI068613 to S.H.E.) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1R01-AI095068 to S.H.E.).

Disclosures: M.M.C. gave a presentation at a meeting sponsored by Idaho Technology (marketer of the LightScanner platform and reagents designed specifically for HRM analysis).

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.08.008.

References

- 1.Wittwer C.T. High-resolution DNA melting analysis: advancements and limitations. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:857–859. doi: 10.1002/humu.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittwer C.T., Reed G.H., Gundry C.N., Vandersteen J.G., Pryor R.J. High-resolution genotyping by amplicon melting analysis using LCGreen. Clin Chem. 2003;49:853–860. doi: 10.1373/49.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittwer C.T., Ririe K.M., Andrew R.V., David D.A., Gundry R.A., Balis U.J. The LightCycler: a microvolume multisample fluorimeter with rapid temperature control. BioTechniques. 1997;22:176–181. doi: 10.2144/97221pf02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed G.H., Kent J.O., Wittwer C.T. High-resolution DNA melting analysis for simple and efficient molecular diagnostics. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:597–608. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tindall E.A., Petersen D.C., Woodbridge P., Schipany K., Hayes V.M. Assessing high-resolution melt curve analysis for accurate detection of gene variants in complex DNA fragments. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:876–883. doi: 10.1002/humu.20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gundry C.N., Vandersteen J.G., Reed G.H., Pryor R.J., Chen J., Wittwer C.T. Amplicon melting analysis with labeled primers: a closed-tube method for differentiating homozygotes and heterozygotes. Clin Chem. 2003;49:396–406. doi: 10.1373/49.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery J.L., Sanford L.N., Wittwer C.T. High-resolution DNA melting analysis in clinical research and diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:219–240. doi: 10.1586/erm.09.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slinger R., Desjardins M., Moldovan I., Harvey S.B., Chan F. A rapid, high-resolution melting (HRM) multiplex PCR assay to detect macrolide resistance determinants in group A streptococcus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa J.M., Cabaret O., Moukoury S., Bretagne S. Genotyping of the protozoan pathogen Toxoplasma gondii using high-resolution melting analysis of the repeated B1 gene. J Microbiol Methods. 2011;86:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Towler W.I., James M.M., Ray S.C., Wang L., Donnell D., Mwatha A., Guay L., Nakabiito C., Musoke P., Jackson J.B., Eshleman S.H. Analysis of HIV diversity using a high-resolution melting assay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:913–918. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cousins M.M., Laeyendecker O., Beauchamp G., Brookmeyer R., Towler W.I., Hudelson S.E., Khaki L., Koblin B., Chesney M., Moore R.D., Kelen G.D., Coates T., Celum C., Buchbinder S.P., Seage G.R., 3rd, Quinn T.C., Donnell D., Eshleman S.H. Use of a high resolution melting (HRM) assay to compare gag, pol, and env diversity in adults with different stages of HIV infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cousins M.M., Ou S.S., Wawer M.J., Munshaw S., Swan D., Magaret C.A., Mullis C.E., Serwadda D., Porcella S.F., Gray R.H., Quinn T.C., Donnell D., Eshleman S.H., Redd A.D. Comparison of a high resolution melting (HRM) assay to next generation sequencing for analysis of HIV diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3054–3059. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01460-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James M.M., Wang L., Musoke P., Donnell D., Fogel J., Towler W.I., Khaki L., Nakabiito C., Jackson J.B., Eshleman S.H. Association of HIV diversity and survival in HIV-infected Ugandan infants. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shendure J., Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J., Chiodini R., Badr A., Zhang G. The impact of next-generation sequencing on genomics. J Genet Genomics. 2011;38:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James M.M., Wang L., Donnell D., Cousins M.M., Barlow-Mosha L., Fogel J.M., Towler W.I., Agwu A.L., Bagenda D., Mubiru M., Musoke P., Eshleman S.H. Use of a high resolution melting assay to analyze HIV diversity in HIV-infected Ugandan children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:e222–e228. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182678c3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keele B.F., Giorgi E.E., Salazar-Gonzalez J.F., Decker J.M., Pham K.T., Salazar M.G. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H.Y., Giorgi E.E., Keele B.F., Gaschen B., Athreya G.S., Salazar-Gonzalez J.F., Pham K.T., Goepfert P.A., Kilby J.M., Saag M.S., Delwart E.L., Busch M.P., Hahn B.H., Shaw G.M., Korber B.T., Bhattacharya T., Perelson A.S. Modeling sequence evolution in acute HIV-1 infection. J Theor Biol. 2009;261:341–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salazar-Gonzalez J.F., Bailes E., Pham K.T., Salazar M.G., Guffey M.B., Keele B.F., Derdeyn C.A., Farmer P., Hunter E., Allen S., Manigart O., Mulenga J., Anderson J.A., Swanstrom R., Haynes B.F., Athreya G.S., Korber B.T., Sharp P.M., Shaw G.M., Hahn B.H. Deciphering human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission and early envelope diversification by single-genome amplification and sequencing. J Virol. 2008;82:3952–3970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02660-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salazar-Gonzalez J.F., Salazar M.G., Keele B.F., Learn G.H., Giorgi E.E., Li H., Decker J.M., Wang S., Baalwa J., Kraus M.H., Parrish N.F., Shaw K.S., Guffey M.B., Bar K.J., Davis K.L., Ochsenbauer-Jambor C., Kappes J.C., Saag M.S., Cohen M.S., Mulenga J., Derdeyn C.A., Allen S., Hunter E., Markowitz M., Hraber P., Perelson A.S., Bhattacharya T., Haynes B.F., Korber B.T., Hahn B.H., Shaw G.M. Genetic identity, biological phenotype, and evolutionary pathways of transmitted/founder viruses in acute and early HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1273–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page K.A., Landau N.R., Littman D.R. Construction and use of a human immunodeficiency virus vector for analysis of virus infectivity. J Virol. 1990;64:5270–5276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5270-5276.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cousins M.M., Swan D., Magaret C.A., Hoover D.R., Eshleman S.H. Analysis of HIV using a high resolution melting (HRM) diversity assay: Automation of HRM data analysis enhances the utility of the assay for analysis of HIV incidence. PLoS ONE. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051359. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HIV Sequence Compendium. Edited by C Kuiken, B Foley, T Leitner, C Apetrei, B Hahn, I Mizrachi, J Mullins, A Rambaut, S Wolinsky, B Korber. Los Alamos, NM, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics. 2010, pp 4. Available online at http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIV/COMPENDIUM/2010compendium.html.

- 24.Dorn J., Masciotra S., Yang C., Downing R., Biryahwaho B., Mastro T.D., Nkengasong J., Pieniazek D., Rayfield M.A., Hu D.J., Lal R.B. Analysis of genetic variability within the immunodominant epitopes of envelope gp41 from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M and its impact on HIV-1 antibody detection. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:773–780. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.773-780.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.