Abstract

Introduction:

Trigeminal Neuralgia (TGN) is a syndrome characterized by Paroxysmal, shock like hemifacial pain. Among the various treatment options micro vascular decompression (MVD) has gained popularity in the recent years.

Materials and Methods:

182 patients underwent MVD, between 1995–2007 out of 530 patients treated for Trigeminal Neuralgia at our service. All were operated by retro auricular sub occipital craniectomy by a single surgeon using autologous muscle graft. They were assessed for pain relief, complications and the data was analysed.

Results:

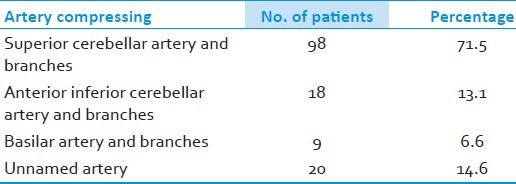

Males were 84 (61.3%) females 53 (38%) with a ratio of 1.5=1. Age ranged from 25-75 years. Duration of symptoms ranging from 6 months to 25 years (average 4-6 years). Seventy seven (56.2% were affected on the right side whereas 60 (43.8%) had pain on the left side. Imaging demonstrated vascular compression in 84 (61%). At surgery superior cerebellar artery was the commonest cause of compression in 71.5%. More than one artery was found in relation to the nerve in 15.3%. There was no mortality, CSF leak 2.9% and transient facial palsy in 2.2% were the notable complications.

Conclusion:

MVD is the procedure of choice for TGN if there is no contraindication for surgery. Adequate tissue respect, meticulous surgical steps and experience will reduce complications. Autologus muscle graft can give comparable and durable results possibly with lesser complications.

Keywords: Microvascular decompression, muscle graft, outcome, trigeminal neuralgia

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia (TGN), also known as tic douloureux or Fothergill's disease, is a clinical syndrome characterized by brief paroxysms of unilateral, lancinating facial pain that is characteristically triggered by cutaneous stimuli, such as a breeze on the face, chewing, talking, or brushing the teeth. Even spontaneous triggers are well known. Dandy in 1934 was the first to implicate compression of the trigeminal sensory root by aberrant arteries and or veins as the cause of trigeminal neuralgia.[1] Gardner and Miklos first reported the success of MVD in trigeminal neuralgia.[2,3] Peter Jenetta and Rand renewed the interest in neurovascular compression theory and popularized the surgical technique. Three main interventional strategies that prevail now: are percutaneous procedures, gamma knife surgery (GSK) and microvascular decompression (MVD). Amongst these, MVD is the procedure which has gained popularity due to its efficacy, relative safety, negligible and associated acceptable neurological complications. The objective of this analysis is to study the various demographical aspects of TGN, and to correlate the preoperative image characteristics with the intraoperative findings. In addition to study the intraoperative findings with reference to the various aspects of vascular compression and other relevant anatomical features that may contribute to the disease and outcomes and surgical complications. We have used only autologus muscle graft for decompression.

Materials and Methods

Patient population

This is a prospective study involving patients undergoing microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia at Manipal Institute for Neurological Disorders (MIND) in the period between July 2002 and June 2007. A total of 176 patients were diagnosed with trigeminal neuralgia during this period of which 137 patients underwent MVD. All of them received a trial of medical management majority with Carbamazepine and Gabapentin. Thirty of them had past history of alternative treatment performed, of which 17 had undergone local alcohol injections, 11 had radiofrequency (RF) ablations and 2 had microvascular decompression earlier. All the patients were operated by a single surgeon.

The inclusion criteria for MVD:

No or minimal pain relief after adequate dose of medication

Inability to tolerate the medications or side effects

Failed previous procedures like RF lesioning and alcohol rhizotomy

Adequate medical fitness for surgery

Recurrent trigeminal neuralgia

Evidence of vascular compression on 3D Fiesta MRI imaging.

The study was conducted based on a protocol. After a detailed history and confirmation with the diagnosis neurological examination was performed in all to exclude secondary causes. MRI brain with 3D fiesta sequence was the main investigation. Routine blood investigations and cardiac evaluation for fitness was performed. Patients were premedicated with antibiotics and antihypertensive drugs whenever necessary.

Operative procedure

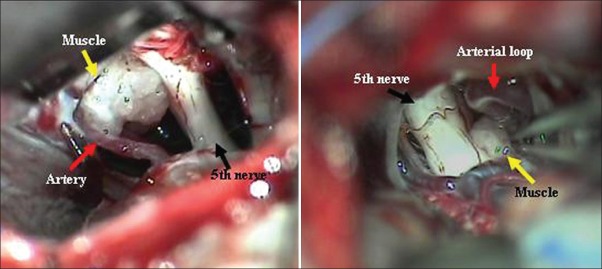

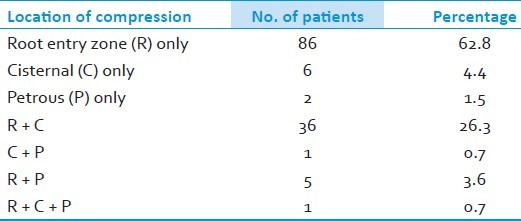

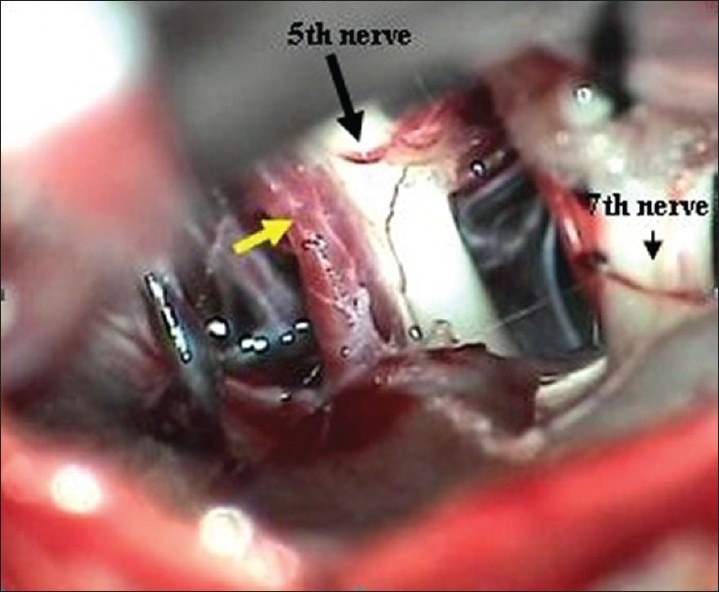

A Standard retromastoid suboccipital craniectomy was performed in all under general anesthesia and a muscle was harvested from the suboccipital region. A small craniectomy of 1.5 cms was performed, dura opened and the CSF was released gradually. With a gentle attraction of cerebellum, trigeminal cistern was approached. Adequate arachnoidal openings will expose the trigeminal nerve. The nerve was inspected from the root entry zone through the cisternal segment up to the parapetrous area all round. The vessels were delineated and separated with gentle microscopic dissection. The muscle is interposed between the nerve and the vessel [Figure 1]. In 2 patients where a large ectactic basilar artery was the compressive agent fibrin glue was used in addition to retain the muscle in place and in another patient a facial sling was used to retract the vessel off the nerve and which was then anchored to the tentorium with prolene stitch.

Figure 1.

Muscle transposition

Follow up

Postoperatively, facial pain assessment was done immediately and daily until discharge. The outcome is classified and documented as excellent, good and poor.

a. Excellent: Immediate or slightly delayed complete pain relief without any need for medications b. Good: Significant pain relief, defined as >75% relief without use of medications c. Poor: No or minimal relief, may need supplementation of medications for relief.

The average postoperative hospital stay was 3 days. The surgical sutures were removed on the 7th – 10th postoperative day, and after 14 days for re-operations. They were followed up after 1 month, 6 months and at 1 year. At the end of 5 years final follow up was done through telephonic interview. The average follow up was 25 months in 60 patients. Those who had recurrence were either re-explored or treated with medications. The possible correlating factors for recurrence were also analyzed.

Results

Demography

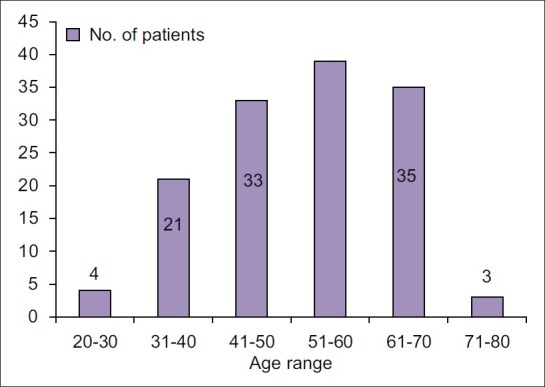

A total of 137 patients underwent MVD for TGN at our service in the period between July 2002 and June 2007. Males were 84 (61.3%) and Females were 53 (38.7%) with a male to female ratio of 1.5: 1. The age ranged from 25 to 75 years with an average of 53 years [Figure 2]. The duration of symptoms ranged from 6 months to 25 years averaging 4.6 years. Right sided symptoms were predominant in 77 (56.2%) patients and 60 (43.8%) had left sided symptoms. The divisions of the 5th nerve involved have been depicted in the Table 1.

Figure 2.

Age range years

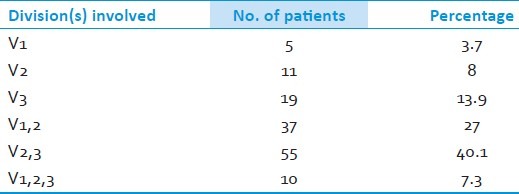

Table 1.

Trigeminal nerve divisions involved

Imaging

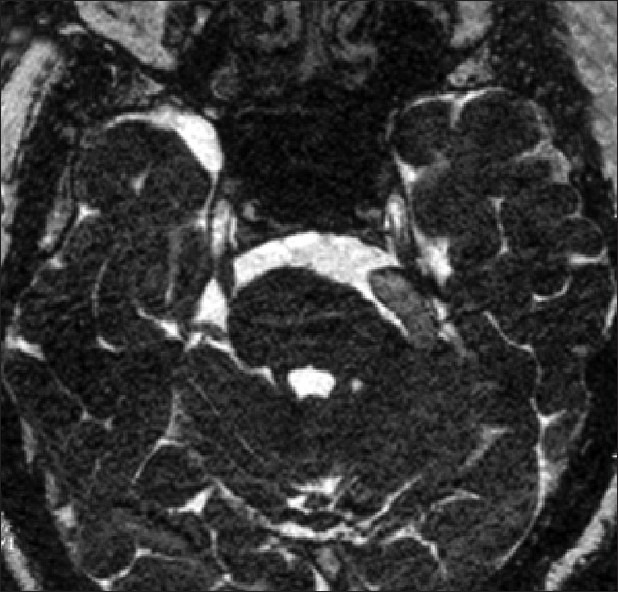

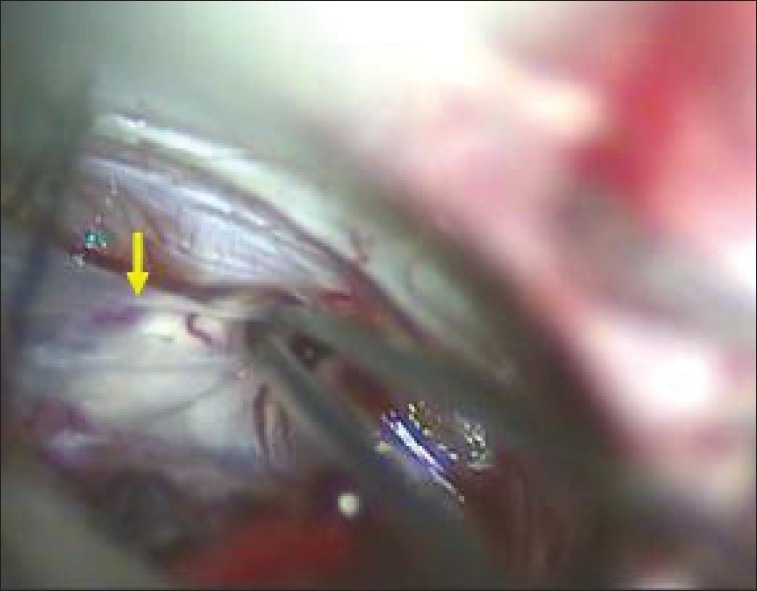

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with 3D FIESTA sequence was performed preoperatively in 124 patients. Imaging showed ipsilateral nerve compression in 84 (61%) patients, contralateral nerve compression in 1 (0.7%), bilateral nerve compression in 12 (8.8%) and no/doubtful compression in 27 (19.7%). Hence, the imaging was useful in diagnosing the condition and identifying the approximate vascular compression and also useful in observing the size of the cisterns and posterior fossa which could probably help in prognostication or predicting the long-term outcome. The imaging also helped us in preparation pre operatively for necessary modifications in procedure in the presence of large ectactic basilar artery [Figure 3]. While it definitely excludes secondary causes, also helps to convince the patients for surgery.

Figure 3.

3D FIESTA MRI sequence showing ectactic basilar artery (yellow arrow) compressing left 5th nerve and distorting the pons

Intraoperative finding

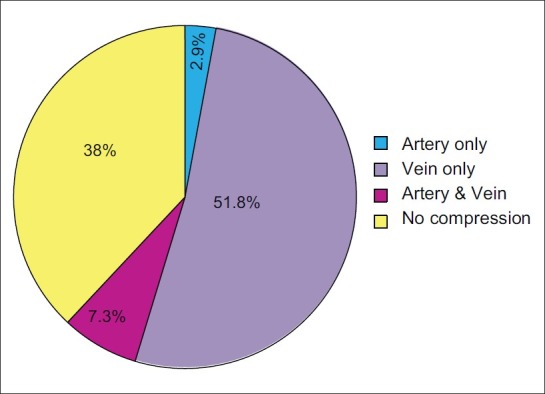

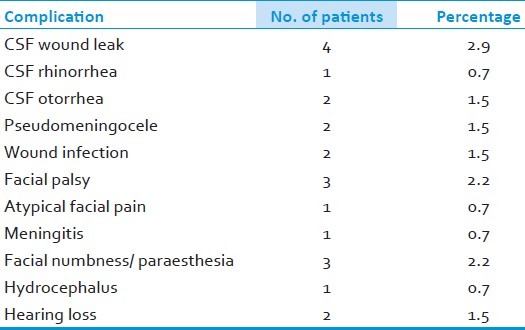

The most common intradural findings [Tables 2–4] were thick arachnoid membrane [Figure 4], with arachnoid bands tethering the trigeminal nerve to the vessel and surrounding structures and others are shallow posterior cranial fossa with narrow cisterns. The commonest cause of vascular loop compression of the nerve is from the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) [Figures 5 and 6]. The SCA commonly makes a shallow, caudal loop and courses inferiorly for a variable distance on the lateral side of the pons and a less frequent source of compression of the trigeminal nerve from the AICA. A dolicoectactic basilar artery also may compress the medial side of the trigeminal nerve, especially so if it is calcified and dolichoectactic. More than one artery compression was found in 15.3%. In many occasions veins, alone or in combination with arteries, were compressing the nerve [Figure 7]. The whole length of the nerve from the pons to the Meckel's cave is inspected thoroughly for any hidden or unseen compressions by smaller vessels. Two of our patients had a bunch of multiple vessels (possibly a vascular malformation) compressing the nerve. Interestingly vessels were seen passing through the nerve between the fascicles in 4 (2.9%) posing technical challenges. Of these 2 were arteries and 2 were veins. Vessels can compress the nerve at different locations, dorsally in 45, ventrally in 37, superiorly in 92 and inferiorly in 42 alone or in combinations. Post operative complications were seen in 8 patients [Table 5].

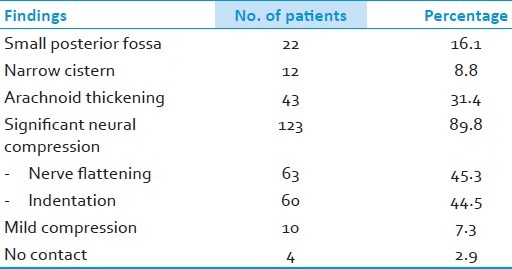

Table 2.

Intraoperative findings

Table 4.

Location of vascular compression

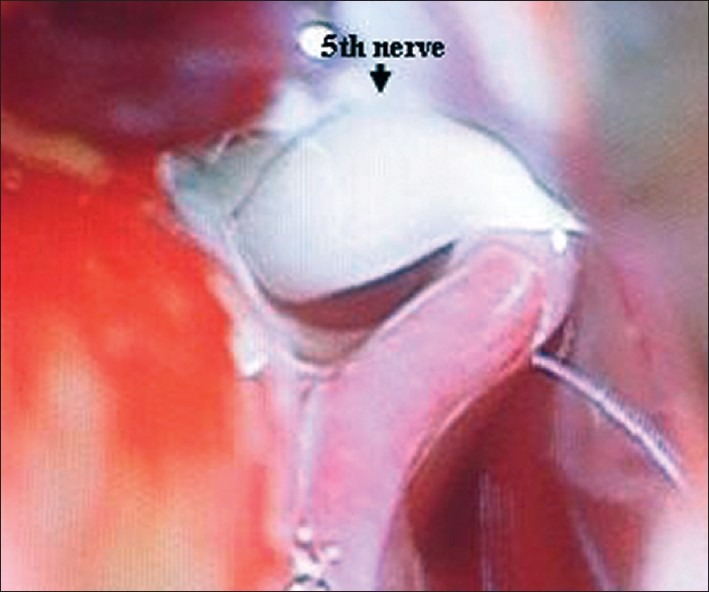

Figure 4.

Thickened arachnoid membrane

Figure 5.

Thinned and displaced nerve

Figure 6.

Superior cerebellar artery (yellow arrow) compression

Figure 7.

Vessel compressing the nerve

Table 5.

Postoperative complications

Table 3.

Specific arterial compression

Outcomes

In our series 108 (78.8%) out of the 137 patients had excellent relief (100 had immediate relief and 8 noticed a complete relief after 2 weeks) and 29 (21.2%) had good relief.

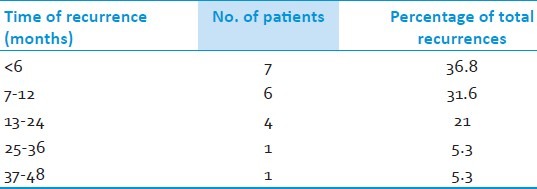

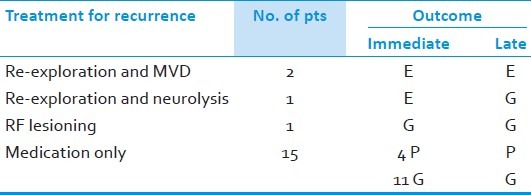

Recurrence of pain was noted in 19 at an interval varied from 3 – 46 months post operatively [Table 6]. Two of them underwent re-exploration for repeat decompression and others were treated with neurolysis, RF ablation or medications. During re exploration we did find the usual perineural adhesions. The muscle graft was intact in majority except that it appeared smaller. We did not find any unusual technical problems, but needs careful dissection and release of all adhesions. Its time taking and needs endurance. We also look around the nerve once again for any missed vessel as we found in one. The author's personal opinion is that the perineural adhesions are much less in intensity in autologous grafts than that of any foreign material used. Only 4 out of 19 had poor pain relief in spite all the measures and eventually were lost for follow up [Table 7]. We did find smaller posterior fossa and narrow cisterns as a frequent association. We really do not know the significance; however, we found the nerve in contact with bone, tent or a vessel often. This makes us postulate that the direct contact of nerve with these anatomical structures could be responsible for the conduction aberrations or precipitating demyelination leading to long term recurrence in this sub group of patients.

Table 6.

Recurrences

Table 7.

Treatment for recurrence

Discussion

In spite of all the proposed controversial theories for the cause of trigeminal neuralgia and its various management strategies, microvascular decompression has been the most convincing and popular method of treatment with better outcomes.

Age has not been a significant criterion for patient selection unless there is severe medical comorbidities preventing a surgical procedure. Our oldest patient was 75 years old with an excellent pain relief. Unlike the reported series our male female ratio was 1.6:1.[4–7] Although the medication alone has been useful in giving pain relief initially; the tolerance, side effects and recurrences make the surgical intervention necessary. We have found MVD to be effective in both typical and atypical TGN equally.

The 3D fiesta sequence of MRI has been an important adjunct as preoperative diagnostic tool especially to identify anatomical variations, and also helps in planning the surgical strategy.

A small posterior fossa and multiple adhesive bands anchoring the vessels to the nerve was seen in majority, could be an important additional factors in the pathophysiology of TGN. The clinical scenario is comparable to neurological dysfunction caused by tethered cord or in meningomyelocele monque. So it is important to remove all these bands to release and mobilize the structures. Though Teflon is a popular material used in many centers due to it's relative inertness, several reports with complications like granuloma formation and chemical meningitis is known.[8,9] We have always used autologus muscle graft as a interposition material and gained good results with practically no serious graft related complications. Moreover the technique of harvesting the muscle is simple and cost effective. Fibrin glue could be used in addition in select situations to retain the graft in place depending on the morphology of the vessels and cisterns as in basilar artery compressions. We had two such occasions and both had good outcomes. Vessels passing between the 5th nerve fascicles are a real surgical challenge requiring gentle neurolysis to relieve the compression. We could not take the risk of sacrificing the vessels or the part of the nerve. Technically it is impossible to insert muscle. Three of such patients had an excellent outcome and 1 had recurrence but had reasonable with pain relief with medications. Surgically separating the veins from the nerve can be very difficult task and time consuming in comparison to the arteries. We have never divided nor sacrificed the veins. Venous decompressions are often incomplete and could be one of the causes of recurrence.

The recurrence rate in our study has been 13.9%. This is comparable to the various reports published in literature which ranges from 3-30%.[10–13] Various causes for recurrences have been reported after MVD. Janetta and Bissonate opined that a continuing elongation of vessels, recanalization of intrinsic divided veins and atrophy of muscle piece as the main cause. They also mentioned that recurrence may be influenced by the procedure – precise position of the nerve in the cistern, degree of complete decompression of the vessel and the kind of graft used.[14] Others have reported recurrence in younger patients, longer preoperative duration of symptoms, only venous or vein and artery compressions, females, males with left sided pain, previous invasive procedures, inability to identify compressing vessels and involvement of 2 or more branches.[9,12,13,15,16]

In our study, recurrence was seen greater in females and with right sided symptoms and with pain involvement of greater than 1 division. Age, duration of symptoms and previous invasive procedures had no significant effect on the recurrence in our series. One patient had TGN associated with Chiari 1 malformation and syringomyelia. MVD was done along with foramen magnum decompression. However, the patient had poor pain relief probably due to the central etiology with a structural abnormality. We could find only 3 other reports in literature with such association of trigeminal neuralgia and Chiari malformation. The possible cause of recurrence in the rest of our patients may be the associated central nuclear dysfunction.[17,18]

The complication rate in our study is 16.1% with no mortality [Table 5]. Most of these were minor and transient. Two had significant residual hearing loss and one had residual facial palsy. But these are comparable to that of other series.[4,16,19–21]

Finally, 97% of our patients had excellent/good results with MVD. Our results have significantly improved with a learning curve and experience after 1 to2 years of consistent performance.[19,16,20]

Conclusion

MVD remains the procedure of choice for TGN (unless surgery is contraindicated) which provides immediate pain relief with good long term success rate and minimal complications. Surgery is safe in all age groups and careful and meticulous surgical steps will reduce the complication rates. Arterial separation is much easier than the venous compressions. The use of muscle graft is still a simple and cost effective option than the artificial materials like Teflon. In author's experience the results are comparable. Consistent surgeons’ experience will improve the overall outcomes. There seems to be a select group of patients with trigeminal neuralgia who are inherently prone for recurrence and their etiology could be different. This makes the trigeminal neuralgia much more interesting and a clinical puzzle which demands further research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Dandy WE. Concerning the cause of trigeminal neuralgia. Am J Surg. 1934;24:447–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner WJ, Miklos MV. Response of trigeminal neuralgia to “decompression” of the sensory nerve root: Discussion of the cause of trigeminal neuralgia. JAMA. 1959;170:1773–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1959.03010150017004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner WJ. Concerning the mechanism of trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:947–58. doi: 10.3171/jns.1962.19.11.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker FG, II, Jannetta PJ, Bisonette DJ, Larkins MV, Jho HD. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1077–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burchiel KJ, Clarke H, Haglund M, Loeser JD. Long-term efficacy of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:35–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.1.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katusic S, Beard CM, Bergstralh E, Kurland LT. Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia: Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:89–95. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolluri S, Heros RC. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Surg Neurol. 1984;22:235–40. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(84)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimaki T, Hoya K, Sasaki T, Kirino T. Recurrent trigeminal neuralgia caused by an inserted prosthesis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138:1307–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01411060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao JJ, Cheng WC, Chang CN, Yang JT, Wei KC, Hsu YH, et al. Reoperation for recurrent trigeminal neuralgia after microvascular decompression. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:562–70. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breeze R, Ignelzi RJ. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Results with special reference to the late recurrence rate. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:487–90. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.4.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsushima T, Yamaguchi T, Inoue TK, Matsukado K, Fukuii M. Recurrent trigeminal neuralgia after microvascular decompression using an interposing technique. Teflon Felt adhesion and the sling retraction technique. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000;142:557–61. doi: 10.1007/s007010050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez-Mejia RO, Limbo M, Cheng JS, Camara J, Ward MM, Barbaro NM. Recurrent or refractory trigeminal neuralgia after microvascular decompression, radiofrequency ablation, or radiosurgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18:e12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.18.5.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun T, Saito S, Nakai O, Ando T. Long-term results of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia with reference of probability to recurrence. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994;126:144–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01476425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ. Management of the failed patient with trigeminal neuralgia. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:334–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SH, Levy EL, Scarrow AM, Kassam A, Jannetta PJ. Recurrent trigeminal neuralgia attributable to veins after microvascular decompression. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:356–62. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200002000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rath SA, Klein HJ, Richter HP. Findings and long-term results of subsequent operations after failed microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:933–8. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosetti P, Taib NOB, Brotchi J, Witte OD. Arnold Chiari Type I Malformation Presenting As a Trigeminal Neuralgia: Case Report. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1122–4. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199905000-00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tortosa A, Arbizu T, Ferran E, Peres Serra J. Arnold Chiari malformation presenting as trigeminal neuralgia. Neurologia. 1991;6:148–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalkanis SN, Eskandar EN, Carter BS, Barker FG. Microvascular decompression surgery in the United States, 1996 to 2000: Mortality rates, morbidity rates, and the effects of hospital and surgeon volumes. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1251–61. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000065129.25359.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaughlin MR, Jannetta PJ, Clyde BL. Microvascular decompression of cranial nerves: Lessons learned after 4400 operations. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:1–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiger HJ. Prognostic factors in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: Analysis of a differential therapeutic approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;113:11–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01402108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]