Abstract

A mucocele of a para-nasal sinus is an accumulation of mucoid secretion and desqua-mated epithelium within the sinus with distension of its walls and is regarded as a cyst like expansile and destructive lesion. If the cyst invades the adjacent orbit and continues to expand within the orbital cavity, the mass may mimic the behavior of many benign growths primary in the orbit. The frontal sinus is most commonly involved, whereas sphenoid, ethmoid, and maxillary mucoceles are rare. Floor of frontal sinus is shared with the superior orbital wall which explains the early displacement of orbit in enlarging frontal mucoceles. Frontal sinus mucoceles are prone to recurrences if not managed adequately. Here, we are evaluating different approaches used to manage various stages of frontal mucoceles which presented to us with orbital complications. Three cases of frontal sinus mucocele are discussed which presented to our OPD with different clinical symptoms and all cases were managed by different surgical approaches according to their severity. We also concluded that it is prudent to collaborate with the neurosurgeons for adequate management of such complex mucoceles by a craniotomy approach.

Keywords: Biopore implant cranioplasty, endoscopic marsupilization, frontal mucocele, orbital complications

Introduction

Mucocoeles of the paranasal sinuses were first described by Langenbeck (1820) under the name of hydatides.[1] Rollet (1909) suggested the name mucocoele.[1] Mucocele of a para-nasal sinus is an accumulation of mucoid secretion and desqua-mated epithelium within the sinus with distension of its walls. It is regarded as a cyst like expansile and destructive lesion. However, the mucocoeles usually behave like real space-occupying lesions that cause bone erosion and the displacement of surrounding structures. The proximity of mucocoeles to the brain may cause morbidity and potential mortality, if left without intervention.[2] The frontal sinus is most commonly involved, whereas sphenoid, ethmoid, and maxillary mucocoeles are rare.[3] The etiology of mucocoeles is multifactorial, which involve inflammation, allergy, trauma, anatomic abnormality, previous surgery, fibrous dysplasia, osteoma, or ossifying fibroma. Obstruction of natural ostia which impairs the drainage of sinus is an important finding. Sinuses are in close relation to the orbit and brain and hence mucocoeles of the paranasal sinuses can spread both intraorbitally and intracranially.[4,5]

The diagnosis of mucocoele is based on a clinical investigation conducted with the aid of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. CT is used in determining the regional anatomy and extent of the lesion, specifically the intracranial extension and the bony erosion. MR imaging is useful in differentiating mucocoeles from neoplasms via contrast enhancement.[6] The mainstay of management of mucocoeles is surgery, which ranges from functional endoscopic sinus surgery to craniotomy, and craniofacial exposure, with or without obliteration of the sinus.[6] As surgical instrumentation has improved and the pathophysiology is better understood, surgical treatment of mucoceles has evolved into procedures that are less invasive and which emphasize more on surgical drainage over ablation.

Three cases of complex frontal mucoceles which presented to us were managed by three different surgical approaches depending on the severity and extent of mucoceles. It is important to realize that management of frontal mucocele requires a “case-based” approach and hence we should not hesitate to treat difficult cases by a craniotomy approach in collaboration with neurosurgeon.

Case Reports

Case 1

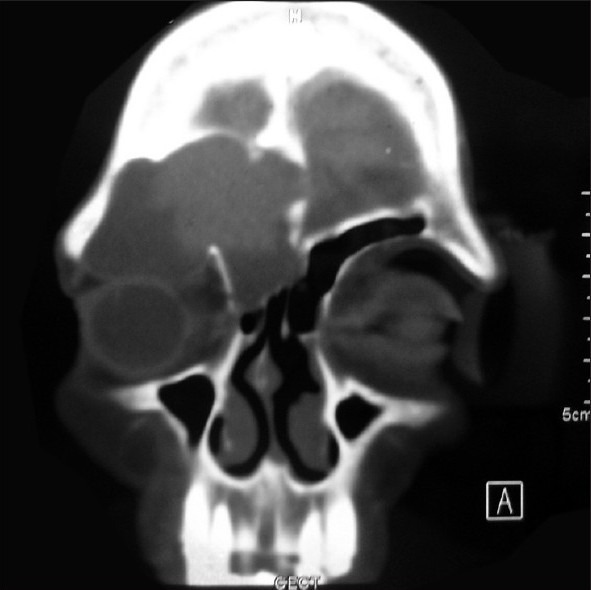

A 61-year-old female presented to our OPD with chief complaints of right superomedial eye swelling for last 2 years. The swelling was associated with excessive watery discharge and pain in right eye as well as pain in right frontal region. There was no history of diplopia or decreased vision from right eye. There was no history of nasal discharge or nasal obstruction. There was previous history of endoscopic marsupilization of mucocele by a private practitioner 2 months back but it recurred again. On physical examination, there was fluctuant swelling present in superomedial region above the right eye. There was mechanical ptosis due to swelling and the eyeball was pushed inferiorly and laterally. Vision was normal in right eye with full extraocular movements in all directions except in supero-medial direction. Pupillary reaction to light and accomodation were normal. Fundus examination was normal. On anterior rhinoscopy, nose was normal. On contrast-enhanced CT, there was large expansile cystic lesion was found to be present involving right frontal sinus containing hypodense contents with expansion of both anterior and posterior table of frontal sinus [Figure 1]. The swelling had so much eroded the anterior and posterior table of frontal sinus that frontal lobe of brain was in direct contact with the eyeball and it was compressing the eyeball and blocking the sinus ostia [Figure 1]. On MRI, the swelling was isointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2. The swelling was in close contact with both orbit and frontal lobes and was almost adherent to both these structures.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan showing a large mucocele with extensive bone erosion of the frontal sinus walls. The mucocele wall is abutting the orbit along with erosion of inter-frontal septum

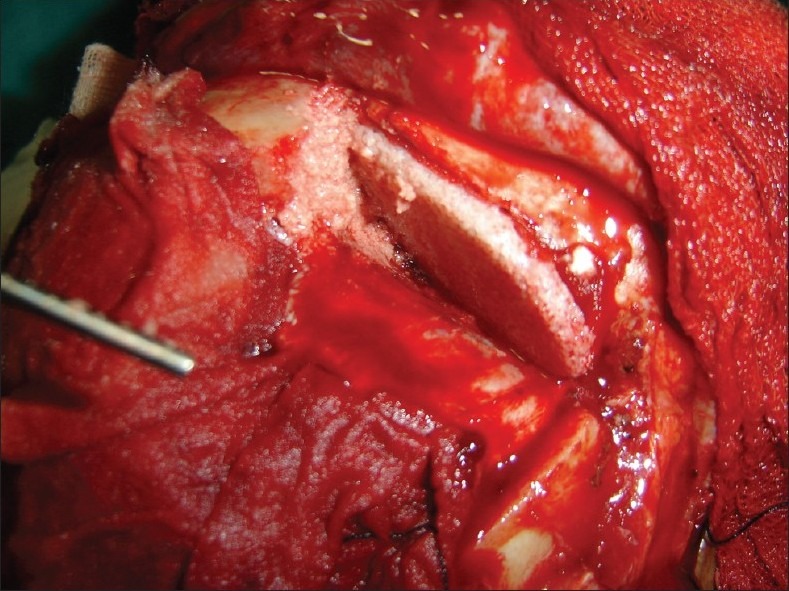

The patient was planned for surgery through the combined ENT-neurosurgical approach. A bicoronal flap incision was made and right-sided frontal craniotomy was done. The anterior and posterior wall of frontal sinus was eroded. The mucocele wall was adherent to dura and the supraorbital wall. Mucocele was dissected slowly from dura and orbit. Mucosa was carefully removed up till the frontal recess area. Complete removal of mucocele was ascertained and whole mucosa of the frontal sinus was scrapped out. Brain was seen to be prolapsing down and compressing the orbit. To prevent this, reconstruction of the posterior table of frontal sinus was necessary. A biosynthetic biopore material was placed between the prolapsing brain and the posterior table of frontal sinus [Figure 2]. By doing this, frontal lobe was segregated from the eyeball and hence compression of eyeball got relieved. The frontal sinus was then completely obliterated with fat and fibrin glue. The bone flap was reposited back and the incision was closed in layers. Post-operatively, there was no episode of CSF leak and wound healing was normal. Post-operative CT scan was done which showed resolution of mucocele with biopore forming the posterior table of frontal sinus [Figure 3]. At present, the patient is on regular follow-up for 3 months and is asymptomatic till date.

Figure 2.

Intra-operative photograph showing placement of synthetic biopore material between dura of frontal lobe and the orbital wall. The material was snugly fitted between the two and thus it prevented the prolapse of brain over the orbit

Figure 3.

Post-operative CT scan showing complete resolution of mucocele with biopore implant in situ

Case 2

A 60-year-old female presented to OPD of our tertiary care hospital with chief complaints of intermittent diplopia along with intermittent right supraorbital swelling for last 1 year. There was no history of decreased vision, nasal discharge, or nasal obstruction. On physical examination, there was fluctuant swelling present in superomedial region above the right eye. Vision was normal in right eye with full extraocular movements in all directions. Pupillary reaction to light and accommodation were normal. Fundus examination was normal. On anterior rhinoscopy, nose was normal. On contrast-enhanced CT, there was large expansile cystic lesion present involving right frontal sinus containing hypodense contents. Left frontal sinus was normal. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy was unremarkable.

The patient was posted for endoscopic marsupilization of the mucocele. The axillary flap approach for frontal sinus as advocated by Peter Wormald was used in this patient. The mucocele sac was incised and the mucus was sucked out. Mucosa was carefully wrapped around the opening which was made for enlargement of frontal sinus ostia. An endotracheal tube was used for stenting the frontal sinus. The endotracheal tube was removed after 6 weeks. The patient is on regular follow-up for last 6 months and is completely asymptomatic till date.

Case 3

The third case was also a female of 50 years who came to our emergency with complains of pain and swelling around right upper eyelid region and frontal sinus area. She also complained of headache and diplopia. The most prominent part of swelling had a punctum through which purulent discharge was coming out just above the upper eyelid. There was downward and outward deviation of the eyeball. She was a known case of rheumatoid arthritis and was on conservative management for that. Immediate CT scan was done which revealed a frontal sinus pyomucocele of size measuring 5 × 3 cm. The frontal sinus floor which was forming the medial orbital roof was eroded and the wall of mucocele was abutting the eyeball [Figure 4]. The anterior wall of frontal sinus was also eroded but the posterior frontal table was intact. She had been operated twice elsewhere where the endoscopic approach was used to enlarge the frontal ostia in both instances.

Figure 4.

Pre-operative CT scan picture showing a moderate sized mucocele with erosion of the frontal sinus floor with mucocele wall attached to the periorbita

In order to prevent further recurrence, the external approach was planned. An extended Lynch-Howarth incision was made and it was extended above the right eyebrow up to its lateral border [Figure 5]. Subcutaneous tissues were dissected till the wall of mucocele was reached. The mucocele was seen to be eroding the anterior table and the floor of the frontal sinus medially. Mucocele was meticulously separated from the periorbita and complete removal was ascertained. Microscope was used to scrape out the mucosa completely from the frontal sinus. Fat was used to obliterate the sinus completely on the right side. The patient was discharged on the second post-operative day. The patient is under constant follow-up now and is being asymptomatic for the last 9 months.

Figure 5.

Intra-operative picture showing supra-ciliary approach through which recurrent mucocele could easily be approached and removed

Discussion

Mucocoeles are collections of mucus enclosed in a sac of lining sinus epithelium within an air sinus resulting from an obstruction to the outlet of the cavity which may cause an expansion of the sinus by resorption of the bony walls. The mucoceles are benign, slow-growing lesions that commonly occur in the frontal or ethmoidal group of sinuses and are rarely found as an isolated intranasal lesion within the confines of the middle turbinate. The sac may be filled with pus as a result of chronic infection, in which event it is known as a chronic pyocoele.

Mucocoeles usually arise due to sinus ostium obstruction, preceded by infection, fibrosis, inflammation, trauma, surgery or blockage by tumors such as osteomas.[3–5]

Detailed histopathologic studies have shown that following obstruction of the frontal recess and subsequent infection within the frontal sinus cavity, continued stimulation of lymphocytes and monocytes leads to the production of cytokines by the lining fibroblasts. These cytokines, in turn, promote bone resorption and remodeling and result in expansion of the mucocele.[7] Cultured fibroblasts derived from frontoethmoidal mucoceles have been shown to produce significantly elevated levels of prostaglandin E2 and collagenase, compared with normal frontal sinus mucosa fibroblasts.[8] Studies have found that high levels of prostaglandin E2 plays a major role in the osteolytic process in mucocoeles and explains the locally-aggressive behavior of these expanding masses.[9]

Approximately 60–89% occur in the frontal sinus, followed by 8–30% in the ethmoid sinuses, and less than 5% in the maxillary sinus. Sphenoid sinus mucoceles are rare.[10] Mucoceles can form at any age, but the majority are diagnosed in patients 40 to 60 years old.[10] Males and females are equally affected. Culture of the aspirated mucocele contents can sometimes confirm the presence of infection. A study demonstrated that the most common isolates were Staphylococcus aureus, alpha-hemolytic streptococci, Haemophilus species, and gram-negative bacilli. The predominant anaerobic isolates were Propionibacterium acnes, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium species.[11]

The clinical presentation of mucocoeles varies with their anatomical site. The onset of symptoms is usually insidious. Patients with frontoethmoidal mucocoeles may develop frontal headache, facial asymmetry, or swelling, as well as ophthalmological manifestations, such as impaired visual acuity, reduced ocular mobility or proptosis. Clinical presentation of the mucocoeles varies from asymptomatic to incapacitating headache and visual disturbance.[3,5] Proptosis (83%) and diplopia (45%) are the most common complaints.[5] On physical examination, periorbital tenderness, swelling, chemosis, decreased visual acuity, and restriction of extraocular movements can be determined.[5] Intracranial extension through erosion of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus can lead to meningitis or CSF fistula.[12] The posterior sinus wall is particularly prone to erosion because it is inherently thin. The tendency for bony erosion and intracranial extension is seen more often in the presence of infection. The presence and direction of the proptosis may be of considerable help in localizing a lesion. A mass at the orbital apex tends to produce a directly forwards proptosis, whilst lesions further forward in the fronto-ethmoidal complex produce a lateral, downwards, and forwards proptosis, similar to that caused by lesions invading the orbit from a large frontal sinus. Ethmoidal lesions in infants produce a proptosis which is characteristically lateral, forwards, and upwards. All this helps to distinguish fronto-ethmoidal mucocoeles from the lesions within the antrum or lacrimal sac with which they are frequently confused.[1]

The diagnosis of a mucocele is based on the history, physical examination, and radiologic findings. There are three criteria for CT diagnosis of a mucocoele: homogeneous isodense mass, clearly defined margin, and patchy osteolysis around the mass.[3,5] Erosion of the sinus wall with marginal sclerosis is also an indicative finding.[5] Typically, mucocoeles tend to be fairly bright on T1W images compared to the brain and iso-hyperintense on T2W images.[5] It is pathognomonic MRI finding for mucocoeles.[5] Neoplastic processes tend to be isointense relative to the brain on both T1 and T2W images.[5] Hyperintensity on T1W images suggests proteinous or hemorrhagic content of a lesion.[3,5] This may lead to misdiagnosis. One of the other pitfalls of MRI in the diagnosis of mucocoeles is that if it contains inspissated proteinaceous content, it could become almost void of signal on T1W and T2W images, like that of air.[5] This would make it difficult to detect on MRI alone. On the CT, however, the inspissated content would be of high density, making diagnosis straightforward.[5] CT and MRI are complementary in complicated cases.[3]

Dermoid cysts, histiocytosis, fungal and tuberculosis infections, fronto-orbital cholesterol granuloma, and other uncommon neoplasms must be considered in the differential diagnosis.[3,5] Because of higher hyperintensity from other processes on T1W images, the differentiation is easy on MRI.[5]

The treatment of mucoceles is surgical. Its goal is to drain the mucocele and ventilate the sinus involved along with eradication of the mucocele with minimal morbidity and prevention of recurrences.[13] Surgical approaches are based on the size, location, and extent of the mucocele. In the presence of infection, adjuvant antibiotic treatment is indicated. Since many of these lesions have an intracranial or intraorbital component, ideally the surgery should not be performed in the setting of an infection. The exception is an acute symptomatic mucopyocele.

Previously, surgical therapy for frontoethmoidal mucoceles involved an external approach (Lynch-Howarth frontoeth-moidectomy) or osteoplastic flaps with sinus cavity oblite-ration.[13] Nowadays, endoscopic drainage is being advocated as treatment of choice for frontal mucoceles as preservation of the frontal sinus mucosa and maintenance of a patent frontal recess result in a better clinical outcome.[14] With the advent and development of endoscopic sinus surgery, the radical procedure has given way to a more functional intervention which is minimally invasive, preserves sinus architecture and notably, leaves no facial scarring.[15] Some authors advise against the placement of a stent due to the possible onset of a decubitus lesion on the periphery of the tube, potentially triggering a retractile scar that would lead to re-stenosis of the ostium.[16] In our experience, it seems a safe and effective option to maintain patency of the frontal sinus's drainage. It is removed 6 weeks later but optimal opening of the recess is observed only after 6 months.

However, there is a series of relative contraindications for an endoscopic endonasal approach such as the presence of any sinonasal involvement preventing drainage of the ostium (e.g., osteoma), the onset of the mucocele in the most external and posterosuperior region of the sinus, and the presence of major sclerosis on the floor of the sinus. In cases where intranasal treatment presents difficulties, it is possible to use an external route[17] or a combined approach with external treatment under endoscopic control. The combined approach should be used in the more severe cases where the anatomy, extent of disease, or previous surgery restricts endoscopic visualization and access to the frontal sinus, as well as in cases where a fistulous tract is already present.[13]

Management in complicated cases of frontal mucocele

Complex cases with extensive intracranial extension have been managed in a number of different ways. Neurosurgeons tend to use an open approach (craniotomy) and to remove the entire cyst lining.[18] Other authors have advocated wide marsupialization via an endoscopic transnasal approach.[14] Alternatively, mucoceles with intracranial extension are approached with a combined craniofacial and endoscopic approach.[19] It is important to realize that mucoceles are prone to recurrences if marsuplization is inadequately done. Endoscopy has become a standard treatment now-a-days but sometimes very large sized complex mucoceles require an open external approach to widen the drainage pathway and to prevent recurrence.

In our first case, the posterior frontal wall was eroded and the brain was prolapsing down into the frontal sinus and compressing the eyeball leading to pulsatile movement of the eyeball. The size of the defect was large. In order to prevent the herniation of brain into the sinus, we planned for frontal craniotomy and also used synthetic biomaterial in the form of a biopore sheet to reconstruct the posterior frontal sinus wall. The sheet was placed between the orbit and the dura. This material was hard and it prevented the eyeball from high brain pressure and thus helped in segregation of brain and the orbit. The endoscopic approach would have been inadequate in this case as it had been tried previously but the swelling recurred.

The second case was treated solely by the endoscopic approach where a wide marsuplization of the mucocele at the frontonasal duct area was done by the axillary flap technique. Mucosa over the frontonasal duct area was carefully preserved and wrapped around the widened opening of the frontal sinus to avoid re-stenosis. Use of stents is controversial but our experiences with stents have been good and we routinely use it after endoscopic marsuplization of frontal mucoceles for around 6 weeks.

Obliteration of frontal sinus after carefully removing complete sinus mucosa is an option if mucoceles are recurrent and are not completely marsupialized by the endoscopic approach. Weber et al[20] advocated that osteoplastic frontal sinus surgery with fat obliteration is very useful and successful in patients in whom frontal sinus cannot be treated effectively through an endonasal approach. Our third case came with recurrence for second time and hence the right supraciliary external approach to open the frontal sinus was planned. The posterior frontal table was intact, hence craniotomy was not thought of in this case. The frontal sinus was adequately opened and after removing the mucosa completely, obliteration by fat was done in this case. Keeping in view of her poor general condition due to rheumatoid arthritis, we planned to be aggressive and hence the external approach was used. Obliteration of frontal sinus is a viable treatment option for such types of recurrent mucoceles. The main disadvantages of this technique are the aesthetic defects that may appear following destruction of the anterior diploë of the frontal sinus, as well as the scar.

Through this article, we are laying emphasis on the fact that frontal sinus mucoceles can have varied presentations depending upon the extent and complexity of the lesion, and hence, conventional preferred surgical approaches cannot be applied in all such cases. Hence, we recommend that each case of mucocele has to be planned according to the severity and extend of presentation and also what approach has been used in previous surgery in recurrent cases. Our primary aim in mucocele surgery should be to ascertain that the drainage pathway should remain patent post-operatively and hence we should ensure to widen it as much as we can during surgery or obliterate it to avoid recurrence.

Conclusion

Mucoceles of the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses are an uncommon cause of unilateral proptosis, but they have characteristic features which enable a diagnosis to be established without undue difficulty. Mucocoeles can cause long-standing proptosis which fluctuates in size, becoming more marked with the common cold. The characteristic radiological features of a mucocele are of considerable value in establishing a diagnosis, as long as proper views of the paranasal sinuses are taken. Endoscopic sinus surgery and marsupialization should be the treatment of choice for asymptomatic simple frontal mucoceles. More radical approaches are required if the size of mucoceles is large and if there appears to be extensive bone erosion causing orbital or intracranial complications.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Alberti PW, Marshall HF, Munro Black JI. Fronto-ethmoidal Mucocele as a cause of Unilateral Proptosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1968;52:833. doi: 10.1136/bjo.52.11.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weitzel EK, Hollier LH, Calzada G, Manolidis S. Single stage management of complex fronto-orbital mucoceles. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:739–45. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan CS, Yong VK, Yip LW, Amritj S. An unusual presentation of a giant frontal sinus mucocele manifesting with a subcutaneous forehead mass. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:397–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suri A, Mahapatra AK, Gaikwad S, Sarkar C. Giant mucoceles of the frontal sinus: a series and review. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:214–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelman RR, Hesselink JR, Zlatkin MB, Crues JV. Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 2035–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galiè M, Mandrioli S, Tieghi R, Clauser L. Giant mucocele of the frontal sinus. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:933–5. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000168999.20258.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund VJ, Milroy CM. Fronto-ethmoidal mucoceles: A histopathological analysis. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:921–3. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100117827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund VJ, Harvey W, Meghji S, Harris M. Prostaglandin synthesis in the pathogenesis of fronto-ethmoidal mucoceles. Acta Otolaryngol. 1988;106:145–51. doi: 10.3109/00016488809107382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chobillion MA, Jankowski R. Relationship between mucoceles, nasal polyposis and nasalisation. Rhinology. 2004;43:219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arrue P, Kany MT, Serrano E, Lacroix F, Percodani J, Yardeni E, et al. Mucoceles of the paranasal sinuses: Uncommon location. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:840–4. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100141854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook I, Frazier EH. The microbiology of mucopyocele. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1771–3. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200110000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voegels RL, Balbani AP, Santos Junior RC, Butugan O. Frontoethmoidal mucocele with intracranial extension: A case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 1998;77:117–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin JS, Lund VJ, Salmon B. Frontoethmoidectomy in the treatment of mucoceles: A neglected operation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:434–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780040074015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn FA, Javer AR. Primary endoscopic management of the frontal sinus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:59–75. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chew YK, Noorizan Y, Khir A, Brito-Mutunayagam S, Prepageran N. Frontal mucocoele secondary to nasal polyposis: an unusual complication. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:374–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannion X, Letarnec A, Legros M, Desphieux JL, Romain P, Schmidt P. À propos des mucocèles. J Fr ORL. 1987;36:227–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bockmühl U, Kratzsch B, Benda K, Draf W. Surgery for paranasal sinus mucocoeles: Efficacy of endonasal micro-endoscopic management and long-term results of 185 patients. Rhinology. 2006;44:62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delfini R, Missori P, Iannetti G, Ciappetta P, Cantore G. Mucoceles of the paranasal sinuses with intracranial and intraorbital extension: Report of 28 cases. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:901–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund VJ. Endoscopic management of paranasal sinus mucoceles. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:36–40. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100139854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber R, Draf W, Keerl R, Kahle G, Schinzel S, Thomann S, et al. Osteoplastic frontal sinus surgery with fat obliteration: Technique and long-term results using magnetic resonance imaging in 82 operations. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1037–44. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]