Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to identify the gene expression pattern specific in alveolar epithelial type II cells (ATII cells) isolated from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Design

Case control.

Setting

Two hospitals in Japan.

Participants

Three patients without COPD and three patients with COPD in microarray analyses. Five smokers without COPD and nine smokers with COPD in the following analyses.

Primary and secondary outcome measured

Primary outcome included identification of differentially expressed genes and activated or inhibited pathways in ATII cells of the patients with COPD, compared to those of the patients without COPD, using Affymetrix gene expression arrays. Secondary outcome included validation of the results of microarray analyses by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR.

Results

We isolated ATII cells from COPD and non-COPD lungs using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. We performed Affymetrix gene expression arrays on both types of ATII cells. Gene set enrichment analyses revealed that two major gene sets were enriched in ATII cells from COPD lungs: interferon-responsive gene sets and gene sets associated with cell cycle progression. Gene ontology term enrichment analyses indicated that among the interferon-stimulated genes, ATII cells in COPD expressed genes such as PSMB8, PSMB9, TAP1 and TAP2 associated with the antigen processing and presentation pathway. We validated the results of the microarray analyses using quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR. In addition, FACS analysis indicated that the percentage of ATII cells to CD45-negative lung cells isolated from COPD lungs were significantly increased more than that from non-COPD lungs.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that interferon-stimulated genes involved in the antigen processing and presentation pathway and genes involved in cell cycle progression were enriched in ATII cells of the patients with COPD. These pathways might alter phenotypes of ATII cells in COPD lungs.

Keywords: Molecular Biology, Respiratory Medicine (see Thoracic Medicine)

Article summary.

Article focus

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality throughout the world and is characterised by small airway diseases and alveolar destruction.

Alveolar epithelial type II cells (ATII cells) serve as progenitor cells for alveolar epithelial cells and have a key role in homeostasis and repair after lung injury.

Despite the important role of ATII cells in alveolar homeostasis and repair, the gene expression profiles of ATII cells in COPD lungs have not been determined yet.

Key messages

ATII cells were isolated from COPD lungs as well as from non-COPD lung using a novel method we previously established.

Microarray analyses indicated that interferon-stimulated genes associated with antigen processing and presentation were enriched in ATII cells in COPD lungs.

At the same time, genes involved in cell cycle progression were upregulated in ATII cells in COPD and the number of ATII cells in COPD lungs were increased more than that of ATII cells in non-COPD lungs.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study elucidated the molecular phenotypes of ATII cells in COPD lungs and highlighted the importance of cell-type-specific analyses in lung diseases.

We could not exclude a possibility that the observed gene expression patterns of ATII cells were influenced by lung cancer, because all the patients had primary lung cancer.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality throughout the world. This condition is characterised by airflow limitation associated with an abnormal inflammatory response in the lungs due to exposure to cigarette smoke and noxious particles or gases.1 Several studies have reported that the abnormal inflammation through T cells, neutrophils and alveolar macrophages injures the component cells of the lung and causes alveolar destruction.2 Lung homeostasis and repair after injuries relies on protective responses by the multiple component cells, and loss of the protective effects can lead to COPD.3–5 Analysis of global gene expression profiles is one of the most powerful tools to identify molecular pathways associated with phenotypes of diseases. So far, several studies examined the gene expression profiles in whole lung tissues of patients with COPD.6–11 However, to our knowledge, there are no reports that describe the gene expression profiles of specific cell types in COPD lungs. To yield deeper insights into molecular bases of cellular phenotypes and pathological processes in COPD, knowledge about gene expression profiles in specific cell types of diseased lungs will be important.12

Alveolar epithelial type II cells (ATII cells) play important roles in maintaining alveolar homeostasis and repair after injury by producing surfactant proteins and acting as a progenitor for alveolar epithelial type I cells.13 Studies based on immunohistochemistry of human lung specimens reported that ATII cells of COPD lungs exhibited increased proliferation, apoptosis and cellular senescence,14 15 suggesting an impairment in COPD ATII cells. Despite such crucial roles of ATII cells, however, neither gene expression profiles nor molecular pathways of ATII cells in COPD lungs have been evaluated.

We recently established a novel method for purifying ATII cells from adult human lungs by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).16 On the basis of the expression patterns of epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM, also known as CD326) and T1α (also known as podoplanin) combined with an FACS sorting technique, more than 95% pure ATII cells can be isolated. The purity is superb compared with the previous method.16 In this study, we report the gene expression profiles of pure ATII cells isolated from lungs of patients with COPD utilising this FACS-based protocol.

Methods

Lung tissue samples and patient population

Human lung tissues were obtained from patients who underwent lung resection at the Department of Thoracic Surgery at Tohoku University Hospital or at the Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital. The characteristics of the six patients analysed by microarray are provided in table 1. The characteristics of an additional 14 patients analysed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) for validation of the microarray data are shown in table 2. Airflow limitation was determined by spirometry and was defined as a postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity<70%, and severity was classified in accordance with the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria.1 We excluded patients diagnosed with respiratory disorders other than COPD, such as asthma or bronchiectasis. We also excluded patients who had been given chemotherapy before surgery. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Tohoku University School of Medicine and the Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital. All patients gave their informed consent.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the microarray analysis

| Age | Gender | Pack-years | FEV1/FVC (%) | FEV1 (%pred) | GOLD stage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-COPD | 70 | F | 0 | 78.0 | 122.9 | – |

| 81 | F | 0 | 70.2 | 98.9 | – | |

| 44 | M | 2 | 83.6 | 106.5 | – | |

| COPD | 59 | M | 20 | 69.4 | 106.7 | I |

| 69 | M | 40 | 58.3 | 64.9 | II | |

| 70 | M | 51 | 51.3 | 78.0 | II |

All patients underwent lung surgery because of primary lung cancer. pred, predicted; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the qRT-PCR validation and FACS analysis to calculate the percentage of ATII cells in CD45-negative lung cells

| Non-COPD (n=5) | COPD (n=9) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.4±14.4 | 71.9±12.9 | 0.4782 |

| Gender, male/female | 5/0 | 9/0 | |

| Pack-years, median (range) | 61.5 (1.0–160.0) | 50.0 (11.5–127.5) | 0.5078 |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 81.6±7.4 | 55.9±11.3 | 0.0007 |

| FEV1 (%pred) | 99.9±12.6 | 74.8±20.4 | 0.0292 |

| GOLD stages I/II/III/IV | – | 3/5/1/0 |

All patients underwent lung surgery due to primary lung cancer. Values are the means±SD unless stated otherwise.

ATII, alveolar epithelial type II; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR.

Isolation of alveolar epithelial type II cells from human lung tissues

The human ATII cells were isolated as previously described.16 Additional details are provided in the online data supplement.

Immunofluorescence staining

We performed immunofluorescence staining as previously described.16 Additional details are provided in the online data supplement.

RNA extraction and microarray analyses

We extracted total RNA and performed gene expression array analysis using the GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California, USA) as previously described.17 The microarray data were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO Series accession no. GSE29133). To identify gene signature-based differences between non-COPD and COPD ATII cells, we performed GSEA18 downloaded from the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis website (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). Ranked expression lists were derived from GeneSpring GX software V.10.0 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). The genes represented by more than one probe were collapsed to the probe with the maximum value. The gene set database used was that of functional sets: c2.all.v3.0.symbols.gmt. The number of permutations was 1000. Gene ontology term enrichment was analysed by the Functional Annotation Clustering Tool in the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID V.6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov).19 The major gene ontology terms associated with each group were manually summarised based on gene-term enrichment buttons provided for each functional group.20

cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR

cDNA was synthesised from the total RNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Individual mRNA species were quantified by qRT-PCR using specific primer sets purchased from Qiagen (Supplemental methods in the online data supplement). A primer set specific for GAPDH (Qiagen) was also used for normalisation. Real-time qPCR was conducted using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The relative expression levels of the specific mRNAs were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.21 Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed according to a previous report.17 The information about PCR conditions was described in the online data supplement.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as the means±SD. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism V.5.0d (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA). Sets containing two groups of data were analysed using unpaired t test unless otherwise stated. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Isolation of alveolar epithelial type II cells from COPD lungs

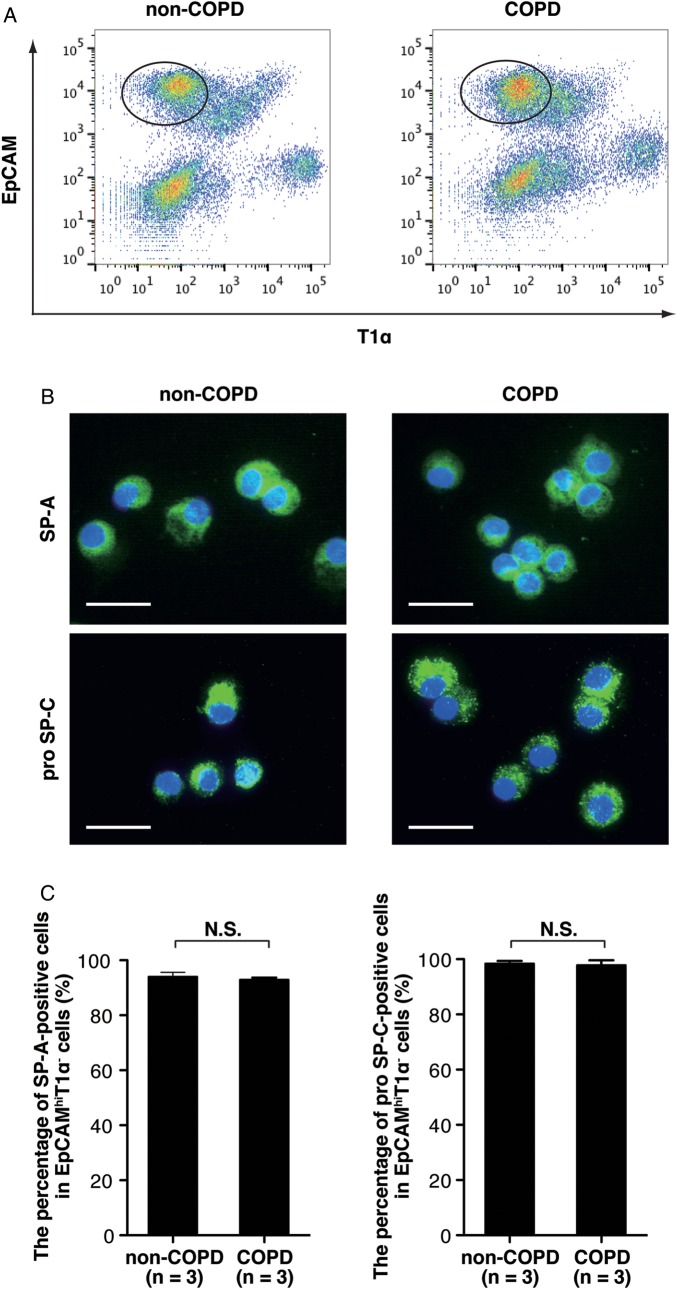

We previously demonstrated that ATII cells could be purified from human lungs as EpCAMhi/T1α− cells using FACS.16 To determine whether ATII cells could also be purified from COPD lungs, we sorted the EpCAMhi/T1α− subset from COPD or non-COPD lungs (figure 1A). The characteristics of the six patients analysed by microarray are described in table 1. Histology of lung tissues analysed in the microarray analyses were shown in figure S2 in the online data supplement. The lung tissues from non-COPD patients showed normal alveolar structure without alveolar destruction or remodelling (see online supplementary figure S2A and B), while the tissues from COPD patients displayed emphysema and bronchiolar wall thickening with infiltration of inflammatory cells (see online supplementary figure S2C and D). We prepared cytospin samples and evaluated the percentage of either SP-A+ or pro-SP-C+ cells in the EpCAMhi/T1α− cells. We found no significant difference in the percentage of SP-A+ or pro-SP-C+ cells in the EpCAMhi/T1α− cells sorted from COPD or non-COPD lungs (figure 1B and C). These data demonstrate that ATII cells were isolated from COPD lungs and non-COPD lungs.

Figure 1.

ATII cells were purified from COPD lungs and from non-COPD lungs. (A) Representative scattergrams showing the expression of EpCAM and T1α from non-COPD and COPD lung tissues. The EpCAMhi/T1α− subset (gates in the scattergrams) indicates the ATII cell population as previously described.16 (B) Representative immunofluorescence staining for ATII cell markers (SP-A and pro SP-C) on EpCAMhi/T1α− cells sorted from COPD or non-COPD lungs. Scale bars, 20 μm. (C) The bar chart shows the percentage of either SP-A or pro-SP-C-positive cells in the EpCAMhi/T1α− cells isolated from COPD (n=3) or non-COPD lungs (n=3). ATII, alveolar epithelial type II; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; N.S., not significant. The data represent means±SD. SP-A, surfactant protein-A; pro-SP-C, pro-surfactant protein-C.

Gene expression analyses of alveolar epithelial type II cells isolated from COPD lungs

We performed the Affymetrix gene expression array with Microarray Suite V.5.0 (MAS 5.0) algorithm on three replicates of ATII cells sorted as EpCAMhi/T1α− cells from either COPD or non-COPD lungs. The characteristics of the patients are shown in table 1. We verified that genes known to be expressed by ATII cells, including SFTPA1, SFTPA2, SFTPB, SFTPC, SFTPD, ABCA3 and SLC34A2, were flagged as present in the EpCAMhi/T1α− cells and that there was no significant difference in the expression values of these genes between COPD and non-COPD samples (data not shown).

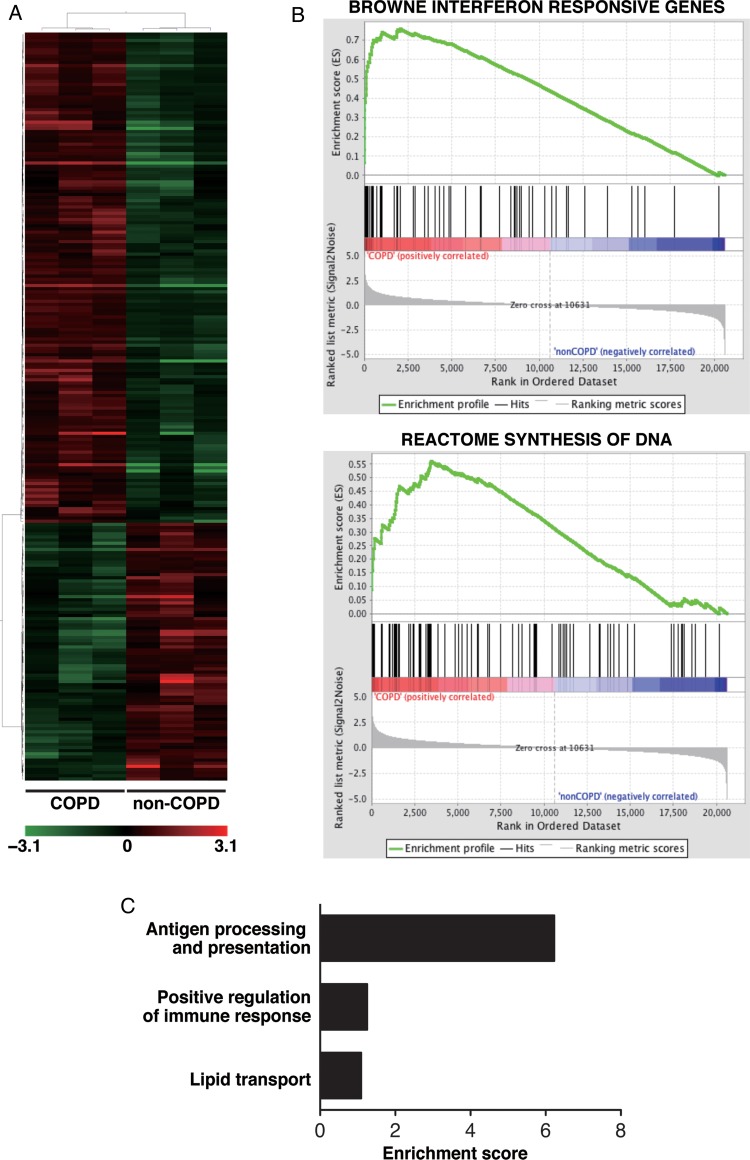

First, we identified genes differentially expressed by at least twofold in COPD ATII cells compared to non-COPD ATII cells. We found that 156 genes were upregulated and 82 were downregulated in COPD ATII cells (fold change>2.0, p<0.05; figure 2A, table S1 and S2 in the online data supplement). To interpret the microarray data and to clarify biological pathways in ATII cells in COPD lungs, we compared transcripts of the ATII cells between COPD and non-COPD lungs using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA V.2.0; http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). We identified 63 gene sets enriched in ATII cells from COPD patients and two gene sets enriched in ATII cells from non-COPD patients using a false discovery rate (FDR) calculation (P<0.05) to account for multiple hypothesis testing (table S3 and S4 in the online data supplement). Notably, seven gene sets associated with ‘interferon-responsive gene sets’ were classified in the top 20 gene sets (see online supplementary table S3). To verify the upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in ATII cells from COPD lungs, we compared the mRNA expression of several ISGs in COPD and non-COPD ATII cells using semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis. We found that IFI44L,22 EPSTI1,23 PSMB924 and ISG1522 were upregulated in ATII cells from COPD lungs (see online supplementary figure S3). In addition to the interferon-responsive gene sets, we found that gene sets associated with DNA synthesis were enriched in ATII cells from COPD lungs (see online supplementary table S3 and figure 2B). FACS analysis confirmed that the ratio of EpCAMhi/T1α− cells (ATII cells) in CD45− lung cells was significantly increased in the COPD group (n=9), more than that in the non-COPD group (n=5; 43.1±12.2 vs 24.8±8.6%, mean±SD, P=0.012). The patients’ characteristics for the FACS analysis are shown in table 2.

Figure 2.

Gene expression analyses in ATII cells in COPD lungs. (A) Hierarchical clustering analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes in ATII cells in COPD lungs (n=3) compared to ATII cells in non-COPD lungs (n=3). Hierarchical clustering analysis revealed the clear separation of gene expression of COPD-ATII cells from non-COPD-ATII cells. (B) Representative GSEA enrichment plots of an interferon-responsive gene signature and a gene set associated with DNA synthesis. (C) Gene ontology term enrichment analysis for upregulated genes in COPD ATII cells. ATII, alveolar epithelial type II; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

A previous report demonstrated that the expression levels of more than 300 genes were regulated by interferons and that those genes were classified into functional categories.24 Next, we performed gene ontology term enrichment analysis using the web-based database (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) V.6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) to examine the classification of the differentially expressed genes into functional categories, including the interferon-stimulated genes. The functional annotation clustering in DAVID revealed that genes associated with antigen processing and presentation, such as TAP1, TAP2, PSMB8, PSMB9, PSMB10, HLA-B and HLA-C (figure 2C, see online supplementary tables S5 and S6), were enriched in the gene set that was upregulated in the COPD samples. These genes are known to be induced by IFN-γ24 and to be involved in MHC class I pathway.25

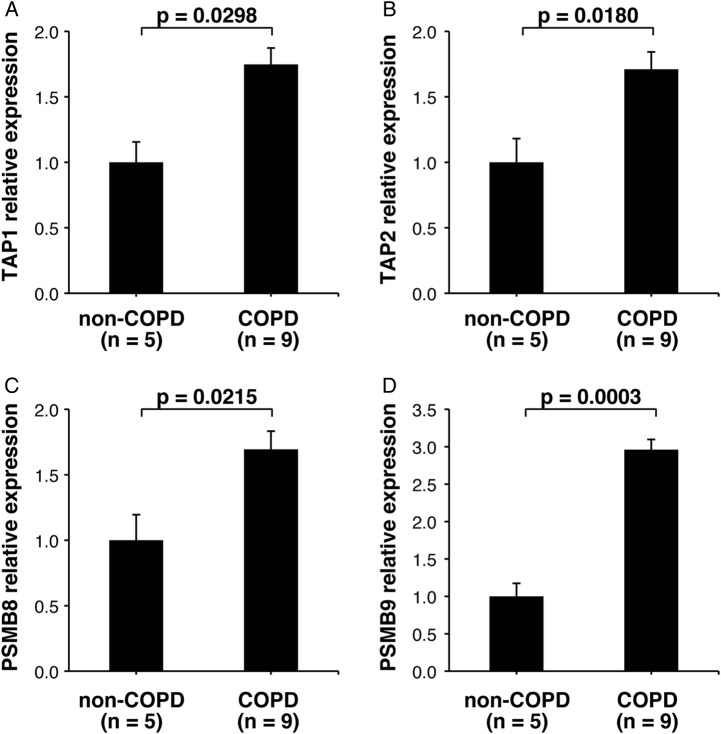

Upregulation of the antigen processing and presentation pathway in ATII cells from COPD lungs

Because gender and the smoking history between COPD and non-COPD patients in the microarray analysis were not matched, we collected an additional set of RNA samples from ATII cells from a second set of patients and used qRT-PCR to validate the upregulation of the antigen processing and presentation pathway in ATII cells of COPD lungs. The characteristics of the patients whose cells were used for the qRT-PCR validation are shown in table 2. In this set of samples, which were matched for gender and tobacco-smoking history, we verified that the expression levels of TAP1, TAP2, PSMB8 and PSMB9 genes were increased in COPD ATII cells compared to non-COPD ATII cells (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR assay for messenger RNA expression levels of genes involved in the MHC class I antigen processing and presentation pathway in ATII cells isolated from non-COPD and COPD patients. (A) TAP1, (B) TAP2, (C) PSMB8 and (D) PSMB9. The data are shown as relative expression values calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method after normalisation to an endogenous control (GAPDH). Bar charts indicate means and SDs. p Values were determined using unpaired t test. MHC, major histocompatibility complex; ATII, alveolar epithelial type II; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the gene expression profiles in pure ATII cell populations from patients with COPD with those from patients without COPD. We showed that interferon-stimulated genes were upregulated in ATII cells from COPD lungs. In addition, we demonstrated that ATII cells from COPD lungs strongly expressed genes associated with the antigen processing and presentation pathway. Most of the patients with COPD exhibited pulmonary emphysema with characteristics of alveolar wall destruction and alveolar space enlargement. ATII cells have key roles in homeostasis and repair after injury in the alveoli.13 Thus, elucidation of the phenotypes of ATII cells in COPD could provide novel insights into the biological and pathological processes of COPD. However, there are few studies on specific characteristics of ATII cells in COPD lungs. One previous study demonstrated that cell turnover (ie, apoptosis and proliferation) was enhanced in ATII cells in COPD lungs.14 Another study reported that ATII cells from COPD patients exhibited cellular senescence, as shown by the accumulation of p16, p21 and lipofuscin.15 Chen et al26 reported that cigarette smoking induced overexpression of hepatocyte growth factor in ATII cells. However, neither gene expression profiles nor molecular pathways specific for ATII cells in COPD lungs have previously been described. Recently, we established a novel method for isolating pure ATII cells from adult human lungs by FACS.16 This new method enabled us to perform gene expression arrays on pure ATII cells isolated from COPD lungs.

Our microarray data demonstrated that interferon-stimulated genes were enriched in ATII cells in the lungs of COPD patients (figures 2 and 3, online supplementary tables S1 and S3). These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that IFN-γ has a key role in the alveolar destruction in COPD. Wang et al27 demonstrated that targeted overexpression of IFN-γ in the adult murine lung caused pulmonary emphysema. Ma et al28 reported that emphysematous changes induced by cigarette smoke exposure were significantly ameliorated in IFN-γ knockout mice. Studies on human specimens showed that IFN-γ-expressing CD8 T cells were increased in both peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in COPD patients.29 30 In addition, a polymorphism of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), a factor downstream from IFN-γ stimulation, was associated with the COPD phenotype.31 Notably, our microarray data showed that interferon-responsive gene sets were predominantly enriched in ATII cells from COPD lungs (see online supplementary table S3). Furthermore, our microarray data and the previous reports suggest that IFN-γ alters the phenotypes of ATII cells and participates in alveolar destruction in COPD lungs.

Our microarray analysis demonstrated enrichment of interferon-stimulated genes associated with the antigen processing and presentation pathway, such as PSMB8, PSMB9, PSMB10, TAP1 and TAP2, in the ATII cells from COPD patients (online supplementary table S6 and figure 3). The proteins encoded by these genes are involved in the MHC class I pathway.32 Once cytotoxic CD8 T cells recognise specific antigens loaded on the MHC class I molecule, the CD8 T cells kill the somatic cells using proteolytic enzymes, including granzyme A or B and perforin.33 In fact, many lines of evidence support the idea that cytotoxic CD8 T cells accumulate in COPD lungs and induce apoptosis of lung cells in the pathological process of COPD. The numbers of CD8 T cells in the airways33 34 and alveoli35 of patients with COPD are correlated with the airflow limitation. Furthermore, CD8 T cells were shown to be essential for alveolar destruction in a cigarette smoke-induced mouse model of emphysema using CD8 knockout mice.36 The CD8 T cells in the lungs of patients with COPD37 or of cigarette smoke-exposed mice38 exhibited oligoclonal expansion, suggesting that the infiltrated CD8 T cells were antigen-specific. Studies on human lung specimens reported that CD8 T cells expressing granzyme A and B39 or perforin40 infiltrated the COPD lungs. In addition to the accumulation of cytotoxic CD8 T cells in COPD lungs, significantly more apoptotic cells were observed in the lungs of COPD patients than in those of control subjects or those from smokers without COPD.4 Recently, Motz et al used adoptive transfer of T cells from cigarette smoke-exposed mice to Rag2-deficient mice to demonstrate that cigarette smoke exposure generated pathogenic T cells that caused pulmonary emphysema and induced apoptosis of ATII cells.41 Our microarray data and these previous studies suggest that the pathological processes involved in COPD include apoptosis of ATII cells following damage by infiltrating CD8 T cells in which the antigen processing and presentation pathway is upregulated. A recent review by Cosio et al2 suggested that the pathogenesis of COPD includes a component of autoimmunity. In fact, antibodies against primary bronchial epithelial cells were detected in patients with COPD.42 Although no ATII cell autoantigens have been confirmed, it might be possible that ATII cells expressing MHC class I molecules loaded with these putative autoantigens are attacked by CD8 T cells in COPD lungs.

Emphysematous changes in COPD lungs result from repeated injury and repair.1 In epithelial restitution, injured alveolar epithelial cells are replaced by proliferating ATII cells.43 Our microarray data provide a molecular basis for this concept, given that gene sets associated with cell cycle progression, such as those listed in the Reactome database for DNA synthesis and the M–G1 transition, were enriched in ATII cells in COPD (see online supplementary table S3). In addition, our FACS analysis showed that the ratio of ATII cells to the resident lung cells was significantly increased in COPD-affected lungs in the mild and moderate stages of the disease over that in non-COPD-affected lungs. These results are consistent with a previous immunohistochemical study reporting that alveolar epithelial cells in COPD-affected lungs proliferated more than those in non-COPD-affected lungs.14 However, it remains unclear as to which signalling pathway regulates the proliferation of ATII cells during the pathologic process of COPD and whether there are differences in gene expression associated with cell cycle progression among the mild, moderate and severe stages of COPD. Further studies will be required to determine these issues.

To our knowledge, there are currently four published studies that have characterised gene expression patterns of whole-lung tissues of patients with COPD.6–11 However, these studies failed to identify the upregulation of the antigen processing and presentation pathway in COPD lungs. One possible reason for the differences is that we focused on the gene expression pattern of a specific cell type (ATII cells) rather than whole-lung tissues. It is well known that there are approximately 40 different cell types in the lung.12 It is likely that the proportions of these cell types are different between COPD and non-COPD lungs. Analyses of whole-lung tissues might highlight differences of proportions of cell types contained in COPD lungs but not differences in overall gene expression between COPD and non-COPD lungs. To acquire deeper insight into the molecular mechanisms of lung diseases including COPD, cell type-specific analyses of gene expression, miRNA expression or epigenetics are required.

There are limitations in this study. First, the sample size in microarray analysis was small in each group. We used three individuals per subgroups. A previous study reported that microarray experiments were performed with a small number of biological replicates, resulting in low statistical power for detecting differentially expressed genes and concomitant high false-positive rates.44 To confirm the genes identified through the pathway analyses, we validated the result of the microarray analyses using qRT-PCR (figure 3). Second, all the patients had primary lung cancer. Although we isolated ATII cells from lung tissues obtained from sites away from the tumours, we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed gene expression patterns of ATII cells were influenced by the tumours present in sites distal to the sampling sites.

In summary, we demonstrated that interferon-stimulated genes associated with the antigen processing and presentation pathway were enriched in ATII cells isolated from the lungs of patients with COPD. ATII cells might be more efficiently attacked by infiltrated CD8 T cells in COPD lungs and would undergo apoptosis, resulting in pulmonary emphysema. Regulation of interferon-stimulated genes in ATII cells might be a novel therapeutic target for COPD therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine for technical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: NF, CO and HK designed and performed experiments, and contributed to writing of the manuscript; TT and MY performed gene analyses; TS, SS and TK obtained the informed consent form the patients and contributed to clinical data analyses; RN and MY contributed to the interpretation of the results. The initial draft of the manuscript circulated among all authors for critical revision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 22390163) to HK.

Competing interests: None

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Tohoku University School of Medicine and the Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital. All patients gave their informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosio MG, Saetta M, Agusti A. Immunologic aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2445–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Fijalkowka I, et al. Role of lung maintenance program in the heterogeneity of lung destruction in emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:673–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henson PM, Vandivier RW, Douglas IS. Cell death, remodeling, and repair in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:713–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Voelkel NF. Molecular pathogenesis of emphysema. J Clin Invest 2008;118:394–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golpon HA, Coldren CD, Zamora MR, et al. Emphysema lung tissue gene expression profiling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spira A, Beane J, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Gene expression profiling of human lung tissue from smokers with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:601–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharya S, Srisuma S, Demeo DL, et al. Molecular biomarkers for quantitative and discrete COPD phenotypes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;40:359–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis SM, Larsen JE, Pavey SJ, et al. Expression profiling identifies genes involved in emphysema severity. Respir Res 2009;10:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezzie ME, Crawford M, Cho JH, et al. Gene expression networks in COPD: microRNA and mRNA regulation. Thorax 2012;67:122–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ning W, Li CJ, Kaminski N, et al. Comprehensive gene expression profiles reveal pathways related to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:14895–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franks TJ, Colby TV, Travis WD, et al. Resident cellular components of the human lung: current knowledge and goals for research on cell phenotyping and function. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:763–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herzog EL, Brody AR, Colby TV, et al. Knowns and unknowns of the alveolus. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:778–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokohori N, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Increased levels of cell death and proliferation in alveolar wall cells in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Chest 2004;125:626–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:886–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujino N, Kubo H, Ota C, et al. A novel method for isolating individual cellular components from the adult human distal lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2012;46:422–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujino N, Kubo H, Suzuki T, et al. Isolation of alveolar epithelial type II progenitor cells from adult human lungs. Lab Invest 2011;91:363–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:15545–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Tan Q, et al. The DAVID gene functional classification tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol 2007;8:R183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001;25:402–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantaert T, van Baarsen LG, Wijbrandts CA, et al. Type I interferons have no major influence on humoral autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:156–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Neergaard M, Kim J, Villadsen R, et al. Epithelial-stromal interaction 1 (EPSTI1) substitutes for peritumoral fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Am J Pathol 2010;176:1229–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Veer MJ, Holko M, Frevel M, et al. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J Leukoc Biol 2001;69:912–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neefjes J, Jongsma ML, Paul P, et al. Towards a systems understanding of MHC class I and MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:823–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JT, Lin TS, Chow KC, et al. Cigarette smoking induces overexpression of hepatocyte growth factor in type II pneumocytes and lung cancer cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;34:264–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Zheng T, Zhu Z, et al. Interferon gamma induction of pulmonary emphysema in the adult murine lung. J Exp Med 2000;192:1587–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma B, Kang MJ, Lee CG, et al. Role of CCR5 in IFN-gamma-induced and cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3460–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirai T, Suda T, Inui N, et al. Correlation between peripheral blood T-cell profiles and clinical and inflammatory parameters in stable COPD. Allergol Int 2010;59:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brozyna S, Ahern J, Hodge G, et al. Chemotactic mediators of Th1 T-cell trafficking in smokers and COPD patients. COPD 2009;6:4–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakke PS, Zhu G, Gulsvik A, et al. Candidate genes for COPD in two large data sets. Eur Respir J 2011;37:255–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen PE. Recent advances in antigen processing and presentation. Nat Immunol 2007;8:1041–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Shaughnessy TC, Ansari TW, Barnes NC, et al. Inflammation in bronchial biopsies of subjects with chronic bronchitis: inverse relationship of CD8+ T lymphocytes with FEV1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:852–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saetta M, Di Stefano A, Turato G, et al. CD8+ T-lymphocytes in peripheral airways of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:822–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saetta M, Baraldo S, Corbino L, et al. CD8+ve cells in the lungs of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:711–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeno T, Houghton AM, Quintero PA, et al. CD8+ T cells are required for inflammation and destruction in cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Immunol 2007;178:8090–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korn S, Wiewrodt R, Walz YC, et al. Characterization of the interstitial lung and peripheral blood T cell receptor repertoire in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:142–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motz GT, Eppert BL, Sun G, et al. Persistence of lung CD8 T cell oligoclonal expansions upon smoking cessation in a mouse model of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. J Immunol 2008;181:8036–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vernooy JH, Moller GM, van Suylen RJ, et al. Increased granzyme A expression in type II pneumocytes of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:464–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chrysofakis G, Tzanakis N, Kyriakoy D, et al. Perforin expression and cytotoxic activity of sputum CD8+ lymphocytes in patients with COPD. Chest 2004;125:71–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Motz GT, Eppert BL, Wesselkamper SC, et al. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure generates pathogenic T cells capable of driving COPD-like disease in Rag2-/- mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:1223–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feghali-Bostwick CA, Gadgil AS, Otterbein LE, et al. Autoantibodies in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:156–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kubo H. Molecular basis of lung tissue regeneration. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;59:231–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei C, Li J, Bumgarner RE. Sample size for detecting differentially expressed genes in microarray experiments. BMC Genomics 2004;5:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.