Abstract

Objectives

Oesophageal cancer is the eighth most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, and there is a need for biomarkers to improve diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Sulfatases 2 (SULF2) is an extracellular endosulphatase that regulates several signalling pathways in carcinogenesis and has been associated with poor prognosis. This study evaluates the relationship between SULF2 expression by immunohistochemistry and overall survival in patients with oesophageal cancer.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

Single tertiary care centre.

Participants

We included patients who underwent esophagectomy for invasive oesophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma at a tertiary care centre from 1997 to 2006. We excluded patients with recurrent oesophageal cancer or less than 3 mm invasive tumour on H&E stained slide. A section from each paraffin-embedded tissue specimen was stained with an anti-SULF2 monoclonal antibody.

Outcome measures

A pathologist blinded to overall survival determined the percentage and intensity of tumour cells staining. Vital status was obtained through the Social Security Death Master File, and overall survival was calculated from the date of surgery.

Results

One-hundred patients with invasive oesophageal cancer were identified, including 75 patients with adenocarcinoma and 25 patients with squamous cell carcinoma. The squamous cell carcinoma samples had a higher mean percentage and intensity of tumour cells staining compared with the adenocarcinoma samples. After adjusting for age, sex, race, histological type, stage and neoadjuvant therapy, for every 10% increase in percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2, the HR for death increased by 13% (95% CI 1.01 to 1.25; p=0.03).

Conclusions

The majority of adenocarcinoma samples and all of the squamous cell carcinoma samples had SULF2 staining. The percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2 was significantly associated with overall survival. Thus, SULF2 is a potential biomarker in oesophageal cancer and may have an important role in the management of patients with this disease.

Article summary.

Article focus

Oesophageal cancer is the eighth most commonly diagnosed cancer and sixth most common cause of cancer death worldwide. There is a desperate need for biomarkers to improve diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of this disease.

Sulphatase (SULF2) is an extracellular endosulfatase that regulates several signalling pathways in carcinogenesis and has been associated with poor prognosis in several types of cancer.

This study evaluates the relationship between SULF2 expression by immunohistochemistry and overall survival in 100 patients with oesophageal cancer.

Key messages

We show for the first time SULF2 staining in oesophageal cancer, including the majority of adenocarcinoma samples and all of the squamous cell carcinoma samples.

The percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2 is significantly associated with overall survival in multivariate analysis.

SULF2 is a potential biomarker in oesophageal cancer and may have an important role in the management of patients with this disease.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A major strength of this study is the use tumour samples from a large, carefully selected cohort of patients with oesophageal cancer.

Another major strength of the study is the novelty of SULF2, which may be a hub in the network of signalling pathways critical for cancer development and progression.

A limitation of this study is the lack of functional data that confirm causality of SULF2 in oesophageal cancer cell lines. However, the significant association between increased SULF2 expression and worse overall survival in patients with oesophageal cancer justifies investigation into the role of SULF2 in oesophageal cancer cells, beyond the scope of the present study.

Another limitation of this study is the variability of SULF2 staining across samples. While SULF2 expression by immunohistochemistry is detected in the majority of the oesophageal tumours, it is possible that SULF2 will be most useful as a biomarker in a subset of patients with oesophageal cancer.

Introduction

Oesophageal cancer is the eighth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer death worldwide.1 There are two main histological types, each with distinct risk factors, geographic patterns and temporal trends. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma is associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, obesity and the precursor lesion Barrett's oesophagus; its incidence has increased faster than that of any other cancer in the USA in the past few decades.2 Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma is associated with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and poor nutrition; its incidence remains much higher than that of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in most of the world.3 Patients with oesophageal cancer continue to have a poor prognosis, with 5-year overall survival still less than 15%.4 A greater understanding of the molecular basis of oesophageal cancer, including the development of new biomarkers, is greatly needed to improve the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of patients with this disease.

Heparan sulphate proteoglycans (HSPGs) consist of core proteins that are modified by the covalent addition of heparan or chondroitin sulphate chains.5 These chains are composed of repeating disaccharide units, which are variably sulphated at four different positions. HSPGs perform enumerable signalling functions, using their sulphated chains to bind diverse protein ligands, such as growth factors, morphogens and cytokines. These interactions depend on the pattern of the sulphation modifications with the 6-O-sulphation of glucosamine (6OS) known to be a key for binding many ligands.6 Two recently discovered sulphatases (SULF1 and SULF2) provide a novel mechanism for the regulation of HSPG-dependent signalling by acting on 6OS on the outside of cells. Work by us and others has shown that SULFs are neutral pH, extracellular enzymes which remove 6OS from intact HSPGs; they promote key signalling pathways by mobilising protein ligands (eg, Wnt ligands, GDNF and BMP-4) from HSPG sequestration, thus liberating the ligands for binding to signal transduction receptors.7–10

One or both SULFs are broadly overexpressed at the transcript level in many human cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, head and neck cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, multiple myeloma, gastric carcinoma and glioblastomas.11 12 SULF2 has been directly implicated as a driver of carcinogenesis in pancreatic cancer13, murine and human glioblastoma14, hepatocellular carcinoma15 and non-small cell lung cancer16. Moreover, SULF2 promoter methylation and expression has been associated with overall survival in lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, respectively.15 17 However, there are no reports on SULF2 expression in oesophageal cancer. This study evaluated SULF2 expression by immunohistochemistry and its association with overall survival in a cohort of patients with oesophageal cancer.

Methods

Patients

We identified patients who underwent esophagectomy at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) during the 10-year period from 1997 to 2006. We included patients undergoing primary resection for invasive oesophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Patients undergoing salvage surgery for recurrent oesophageal cancer were excluded. We evaluated cases with at least 3 mm of invasive carcinoma on histological sections and for which corresponding paraffin blocks were available. Clinical data were obtained through review of electronic medical records. Histological data were obtained through review of pathology reports and confirmed by review of H&E-stained sections by a pathologist. Pathological stage was determined by the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.18 Vital status was obtained through the Social Security Death Master File. Overall survival was calculated from the date of surgery. The UCSF institutional review board approved this study.

Immunohistochemistry

A 5 μm section from each paraffin-embedded tissue specimen was stained with a mouse monoclonal antibody to SULF2 (AbD Serotec MCA5692T or Novus Biologicals NBP1-36727)16 at a concentration of 2 µg/ml with avidin-biotin blocking. A pathologist blinded to patient outcome determined the percentage and intensity of tumour cells staining. The percentage of tumour cells staining was scored from 0% to 100%. The pathologist evaluated all of the tumour cells on each slide, so the number of cells evaluated per slide depended on the size of the tumour and varied widely. The intensity of tumour cells staining was assessed at 100×magnification and scored from 0 to 3. A score of 0 represented no staining; 1, weak staining; 2, moderate staining and 3, strong staining. When specimens showed a range of intensity, the mean intensity was recorded. The presence of endothelial cell staining was assessed for each slide and functioned as an internal positive control. Staining of tumour-associated stroma was also noted.

Statistical analysis

Patient baseline characteristics and immunohistochemistry scores were summarised and compared by histological type, using the Student's t test for continuous variables and the χ² test for categorical variables. Survival analysis was performed using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. Age, sex and race were included in the multivariate model a priori. Histological type, stage, grade, neoadjuvant therapy and year of operation were included in the multivariate analysis only if the p value was less than 0.10 in the univariate analysis. We repeated our analyses in prespecified subgroups by histological type (adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma) and neoadjuvant therapy (yes and no). In order to account for the possible misdiagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma arising at the gastro-oesophageal junction as oesophageal adenocarcinoma, we also repeated our analyses in the subgroup of patients with adenocarcinoma, excluding those with tumours located at the gastro-oesophageal junction and not associated with Barrett's oesophagus. For all statistical tests, a two-sided α-level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Stata V.11.

Results

Patients

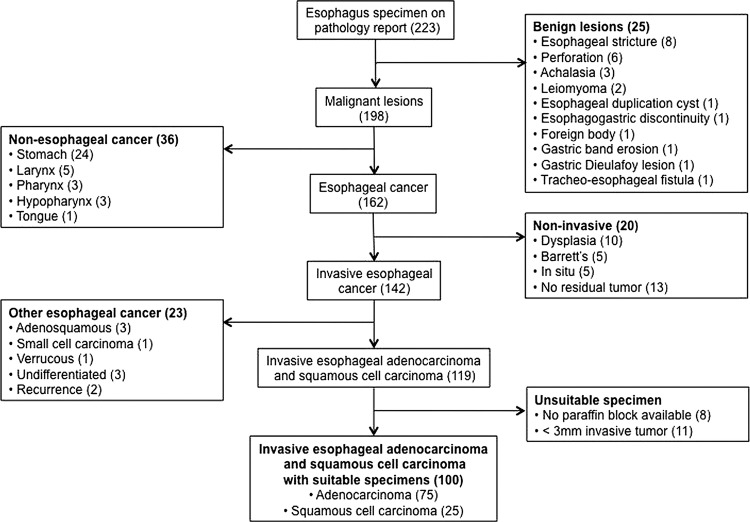

We identified 233 patients who underwent esophagectomy at UCSF during the 10-year period from 1997 to 2006 (figure 1). Of these, 100 patients met our inclusion criteria, including 75 patients with adenocarcinoma and 25 patients with squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Patient selection by review of 223 patients who underwent oesophagectomy from 1997 to 2006.

There were several differences in baseline characteristics between patients with adenocarcinoma and those with squamous cell carcinoma (table 1). Patients with adenocarcinoma had a higher proportion of men (82% vs 52%; p<0.0005). Adenocarcinomas were more often located at the gastro-oesophageal junction and associated with Barrett's oesophagus. Patients with adenocarcinoma had a higher frequency of neoadjuvant therapy and were generally diagnosed and resected at an earlier pathological stage. There was no difference in age, race or ethnicity between histological types.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| All patients (N=100) | Patients with AC (N=75) | Patients with SCC (N=25) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD—years | 64.2±11.6 | 63.9±11.0 | 65.2±13.5 | 0.63 |

| Sex—no. (%) | <0.0005 | |||

| Female | 21 (21) | 9 (12) | 12 (48) | |

| Male | 79 (79) | 66 (88) | 13 (52) | |

| Race—no. (%) | 0.13 | |||

| White | 80 (80) | 62 (84) | 18 (72) | |

| Asian | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (12) | |

| Black | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (4) | |

| Missing | 13 (13) | 10 (13) | 3 (12) | |

| Ethnicity—no. (%) | 0.48 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 90 (90) | 66 (88) | 24 (96) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 | |

| Missing | 8 (8) | 7 (9) | 1 (4) | |

| Location of tumour†—no. (%) | <0.0005 | |||

| Upper oesophagus | 5 (5) | 0 | 5 (20) | |

| Middle oesophagus | 9 (9) | 2 (3) | 7 (28) | |

| Lower oesophagus | 31 (31) | 20 (27) | 11 (44) | |

| Gastro-oesophageal junction | 55 (55) | 53 (71) | 2 (8) | |

| Presence of Barrett's oesophagus—no. (%) | 46 (46) | 46 (61) | 0 | <0.0005 |

| Yes | 54 (54) | 29 (39) | 25 (100) | |

| No | ||||

| Pathological stage—no. (%) | 0.06 | |||

| I | 30 (30) | 27 (36) | 3 (12) | |

| II | 31 (31) | 23 (31) | 8 (32) | |

| III | 37 (37) | 23 (31) | 14 (56) | |

| IV | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 | |

| Histological grade—no. (%) | 0.10 | |||

| 1 (Well-differentiated) | 11 | 11 | 0 | |

| 2 (Moderately differentiated) | 41 | 30 | 11 | |

| 3 (Poorly differentiated) | 44 | 30 | 14 | |

| 4 (Undifferentiated) | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 0.04 | |||

| Yes | 28 (28) | 25 (33) | 3 (12) | |

| No | 72 (72) | 50 (67) | 22 (88) |

*p Values were calculated using the t test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

†Location of tumour was recorded as the most superior location of the tumour in the oesophagus. For example, if the pathology report noted tumour at the upper and middle oesophagus, the location was recorded as upper oesophagus.

AC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry

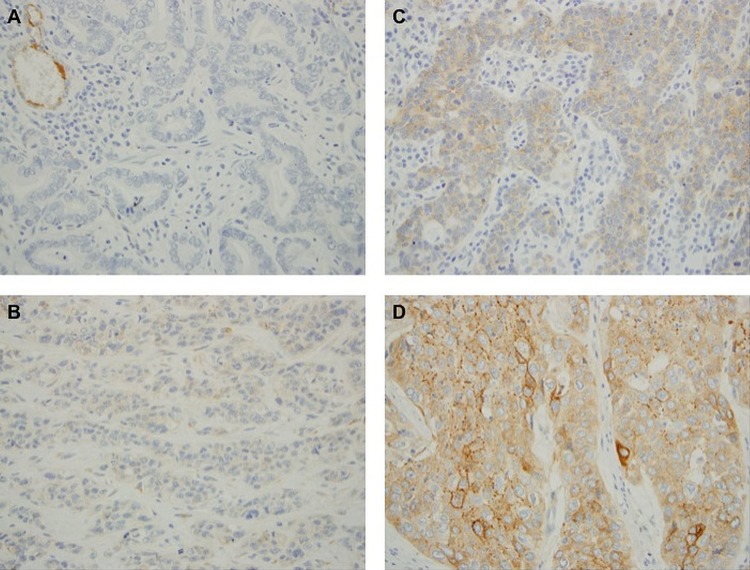

SULF2 staining was detected on 93/100 of the specimens, including 68/75 (91%) adenocarcinoma samples and 25/25 (100%) squamous cell carcinoma samples (figure 2). All samples had endothelial cell staining, which served as an internal positive control.

Figure 2.

Representative sections from adenocarcinoma samples with no staining (A), weak staining (B) and moderate staining (C) and a squamous cell carcinoma sample with strong staining (D). Endothelial cell staining served as an internal positive control, as seen in the upper left corner of (A).

The squamous cell carcinoma samples had a higher mean percentage (49% vs 36%; p=0.06) and intensity (1.9 vs 1.4; p=0.0007) of tumour cells staining compared to the adenocarcinoma samples. Samples from patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy had a lower mean intensity of tumour cells staining (1.3 vs 1.6; p=0.03), but this difference was not evident when patients were stratified by histological type. Neither percentage nor intensity of tumour cells staining was significantly associated with the other clinical and pathological variables, including stage and grade.

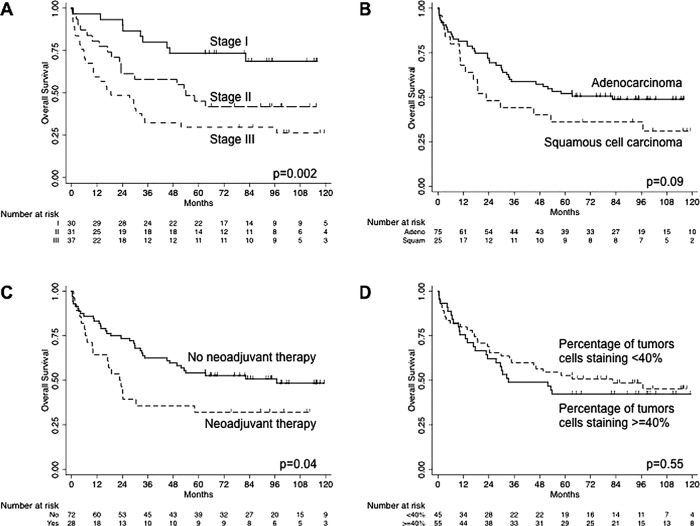

SULF2 staining was present in some adjacent tissues. Among the 75 adenocarcinoma samples, incidental adjacent tissue included squamous epithelium (33), gastric epithelium (24) and Barrett's oesophagus (20). Seventeen (52%) of the samples of adjacent benign squamous epithelium showed SULF2 staining of this epithelium. Staining was generally focal in the basal layer with weak-to-moderate intensity. Seven (29%) of the samples of adjacent benign gastric epithelium showed SULF2 staining of this epithelium, mostly patchy in the basal layer with weak-to-moderate intensity. Fifteen (75%) of the samples of Barrett's oesophagus showed SULF2 staining of this metaplastic epithelium, mostly patchy with weak-to-moderate intensity (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sulphatase 2 staining of adjacent Barrett's oesophagus.

Among the 25 squamous cell carcinoma cases, incidental adjacent tissue included benign squamous epithelium (6), dysplastic squamous epithelium (4) and carcinoma in situ (5). Three (50%) of the samples of adjacent benign squamous epithelium had SULF2 staining, mostly in the basal to middle layers with weak-to-moderate intensity. One (25%) of the samples of dysplastic squamous mucosa demonstrated SULF2 staining. Interestingly, the area with low-grade dysplasia had weak intensity, and the area with high-grade dysplasia had moderate intensity. All 5 (100%) of the samples of carcinoma in situ had SULF2 staining, mostly in the basal layer with moderate intensity.

Survival analysis

Median follow-up time was 53.6 months (IQR, 15–97.6 months). Fifty-five patients died, including 38/75 (51%) patients with adenocarcinoma and 17/25 (68%) patients with squamous cell carcinoma.

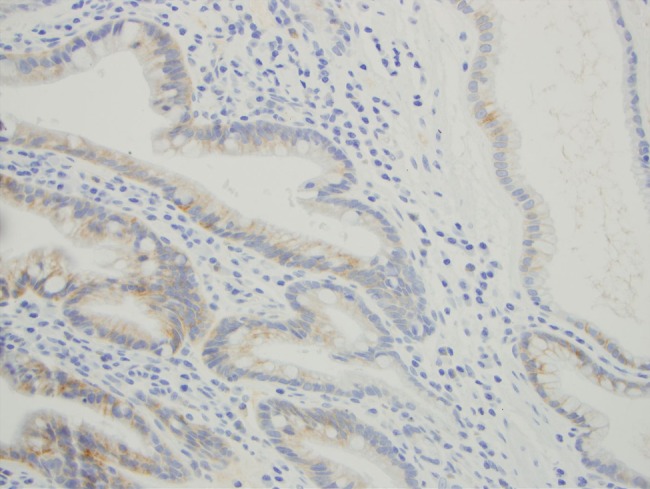

In the univariate Cox proportional hazards models, pathological stage, neoadjuvant therapy and histological type were significantly associated with overall survival; these were included in the multivariate model. Year of surgery and histological grade were not significantly associated with survival; these were not included in the multivariate model. For every 10% increase in the percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2, the risk of death increased by 4%, but this effect was not significant (p=0.42). Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival estimates confirmed these results (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates by (A) stage, (B) histological type, (C) neoadjuvant therapy and (D) percentage of tumours cells staining. p Values were calculated using the log-rank test.

In the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, histological type was no longer associated with overall survival (table 2). Higher stage was still associated with worse survival (p=0.001), and patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy still had a higher risk of death compared to those who did not (p=0.003). The percentage of tumour cells staining was significantly associated with overall survival. After adjusting for age, sex, race, histological type, stage and neoadjuvant therapy, for every 10% increase in percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2, the risk of death increased by 13% (p=0.03).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for overall survival

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.09 | 0.99 to 1.03 | 0.46 | 1.19 | 0.92 to 1.54 | 0.19 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1.17 | 0.61 to 2.21 | 0.64 | 1.30 | 0.61 to 2.78 | 0.50 |

| Race | 0.59 | 0.40 | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Asian | 0.91 | 0.22 to 3.77 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.18 to 4.49 | 0.90 |

| Black | 2.21 | 0.53 to 9.17 | 0.27 | 3.76 | 0.80 to 17.57 | 0.09 |

| Histological type | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Squamous cell | 1.63 | 0.92 to 2.88 | 0.10 | 1.14 | 0.53 to 2.43 | 0.74 |

| Pathological stage | 0.004 | 0.001 | ||||

| I | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II | 2.42 | 1.08 to 5.38 | 0.03 | 2.65 | 1.13 to 6.22 | 0.03 |

| III | 4.01 | 1.88 to 8.55 | <0.0005 | 5.14 | 2.23 to 11.82 | <0.0005 |

| IV | 2.14 | 0.27 to 16.94 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.11 to 8.10 | 0.96 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.78 | 1.02 to 3.11 | 0.04 | 2.65 | 1.38 to 5.09 | 0.003 |

| Percent (per 10%) | 1.04 | 0.95 to 1.14 | 0.42 | 1.13 | 1.01 to 1.26 | 0.03 |

Only percentage, not intensity, of tumour cells staining was significantly associated with overall survival. Subgroup analysis by histological type and neoadjuvant therapy did not show significant associations between percentage or intensity of tumour cells staining and survival.

Discussion

This study showed that higher SULF2 expression by immunohistochemistry is associated with worse overall survival in oesophageal cancer. After adjusting for age, sex, race, histological type, stage and neoadjuvant therapy, for every 10% increase in the percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2, the risk of death increases by 13%. As expected, higher stage was also significantly associated with worse overall survival. Interestingly, patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy had worse overall survival than those who did not. This result likely reflects selection bias, in which patients diagnosed with more aggressive tumours are more likely to receive neoadjuvant therapy.

This study also showed that SULF2 staining differed by histological type, likely reflecting their distinct aetiologies. Squamous cell carcinoma samples had significantly higher percentage and intensity of tumour cells staining than adenocarcinoma samples. These results correspond to our previous findings in non-small cell lung cancer, in which in 10 of 10 squamous cell carcinoma samples showed staining for SULF2, while zero out of 10 adenocarcinoma samples showed staining in the tumour cells.16 However, in the aforementioned study, all squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma samples showed SULF2 staining of tumour stroma cells.

The association of SULF2 and overall survival corresponds to previous findings in two other types of cancer. Lai et al15 showed that increased SULF2 transcript expression was associated with worse overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Tessema et al17 showed that SULF2 promoter methylation was associated with improved overall survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Our results show that increased SULF2 at the protein level is associated with worse overall survival in a third type of cancer, consistent with an important role for this extracellular enzyme in carcinogenesis.

The SULFs were first discovered in a study on quail embryo development, with the human orthologues, SULF1 and SULF2, cloned soon thereafter.10 SULFs have been shown to regulate several signalling pathways by changing the sulphation status of extracellular HSPGs. Ai et al7 established that the SULFs promote canonical Wnt signalling, by removing 6OS from the heparan sulphate chains of HSPGs, allowing the Wnt ligands to interact with its Frizzled receptor, leading to activation of Wnt target genes.

Originally, SULFs were thought to be tumour suppressors, because forced expression of an SULF in several tumour cell lines caused reduced growth-factor signalling by heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor-2 or hepatocyte growth factor, as well as diminished tumorigenicity.19–22 Soon, however, they were thought to play an oncogenic role, as one or both SULF genes were found to be overexpressed in subsets of multiple tumours (breast, pancreatic, hepatocellular carcinoma, head and neck, lung, multiple myeloma and glioblastoma).10 11 13–16 20 23–25 SULF2 in particular has been identified as a candidate cancer-causing gene in two unbiased screening studies in human breast cancer and mouse brain cancer.26 27 Moreover, in pancreatic and lung cancer cell lines, SULF2 knockdown led to reduced proliferation and reduced growth of xenografts in mice, likely due to its effect on canonical Wnt signalling pathway.13 16 In hepatocellular cancer cell lines, overexpression of SULF2 led to increased proliferation and migration and markedly enhanced the tumorigenicity of the cells in nude mice.15 Similarly, a recent study showed SULF2 transcripts and protein upregulation in human malignant astrocytoma, and, using knockdown and transgenic approaches, demonstrated a SULF2-dependent increase in PDGFR signalling, tumour cell proliferation in vitro and tumour growth in vivo.14 The present study is the first to investigate SULF2 in oesophageal cancer.

Our results show that SULF2 was expressed in 93 of 100 human oesophageal tumours. Importantly, high expression of SULF2 was associated with worse prognosis in oesophageal cancer. As a secreted molecule, SULF2 is a potential diagnostic or prognostic biomarker. Current screening programmes for patients with Barrett's oesophagus or severe gastro-oesophageal reflux are ineffective in preventing oesophageal adenocarcinoma, due to the slow rate of progression and resultant low incidence of oesophageal cancer.4 The development of SULF2 as a biomarker may help identify a high-risk group that would make screening more feasible. In our study, 15 out of 20 (75%) adjacent Barrett's oesophagus samples had SULF2 staining. Also, 5 of 5 (100%) adjacent carcinoma in situ samples had SULF2 staining, although 3 of 6 (50%) adjacent benign squamous epithelium had SULF2 staining as well. Future studies are needed to evaluate SULF2 specifically in these precursor lesions as well as in blood or other body fluids.

Given the prevalence and poor prognosis of oesophageal cancer, advances in chemotherapy and targeted therapies based on key molecular pathways are greatly needed. Although further investigations are required for validation of the role of SULF2 in oesophageal cancer, our results raise the possibility that SULF2 could be a therapeutic target. SULF2 is an extracellular enzyme and thus is potentially amenable to inhibition by either antibody-based or small-molecule drugs. SULF1 and SULF2 double knockout mice had increased perinatal mortality, and the mice that did survive had lower body weight28; however SULF1 and SULF2 single knockout mice appear normal and have normal survival, suggesting that each enzyme might be singly targeted.

In conclusion, we show SULF2 expression in oesophageal carcinoma. The vast majority of adenocarcinoma samples and all the squamous cell carcinoma samples had some degree of SULF2 protein expression. Higher percentage of tumour cells staining for SULF2 is significantly associated with worse overall survival in these patients. Patients with oesophageal cancer have an extremely poor prognosis, and SULF2 is a promising biomarker that could play an important role in the diagnosis and prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Loretta Chan at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Immunohistochemistry Core for performing the immunohistochemical staining.

Footnotes

Contributors: NSL was involved in study design, patient selection, data collection, statistical analysis and interpretation and paper writing. MVZ contributed in study design, patient selection, reviewing H&E slides, scoring SULF2 stained slides, data analysis and interpretation and paper revision. SDR and DMJ contributed in data analysis and interpretation and paper revision and HLA contributed in study design, data analysis and interpretation and paper revision. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported in part by The Doctors Cancer Foundation grant A118560 and the American Cancer Society grant IRG-97-150-13. SDR is supported by the NIH grant AI053194.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: UCSF Committee on Human Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demeester SR. Epidemiology and biology of esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2009;3:S2–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1893–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagergren J, Lagergren P. Oesophageal cancer. BMJ 2010;341:c6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, et al. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem 1999;68:729–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamanna WC, Kalus I, Padva M, et al. The heparanome—the enigma of encoding and decoding heparan sulfate sulfation. J Biotechnol 2007;129:290–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ai X, Do AT, Lozynska O, et al. QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol 2003;162:341–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ai X, Kitazawa T, Do AT, et al. SULF1 and SULF2 regulate heparan sulfate-mediated GDNF signaling for esophageal innervation. Development 2007;134:3327–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viviano BL, Paine-Saunders S, Gasiunas N, et al. Domain-specific modification of heparan sulfate by Qsulf1 modulates the binding of the bone morphogenetic protein antagonist Noggin. J Biol Chem 2004;279:5604–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Werb Z, et al. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J Biol Chem 2002;277:49175–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen SD, Lemjabbar-Alaoui H. Sulf-2: an extracellular modulator of cell signaling and a cancer target candidate. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2010;14:935–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bret C, Moreaux J, Schved JF, et al. SULFs in human neoplasia: implication as progression and prognosis factors. J Transl Med 2011;9:72–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nawroth R, van Zante A, Cervantes S, et al. Extracellular sulfatases, elements of the Wnt signaling pathway, positively regulate growth and tumorigenicity of human pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One 2007;2:e392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips JJ, Huillard E, Robinson AE, et al. Heparan sulfate sulfatase SULF2 regulates PDGFRalpha signaling and growth in human and mouse malignant glioma. J Clin Invest 2012;122:911–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Yu C, et al. Sulfatase 2 up-regulates glypican 3, promotes fibroblast growth factor signaling, and decreases survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008;47: 1211–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemjabbar-Alaoui H, van Zante A, Singer MS, et al. Sulf-2, a heparan sulfate endosulfatase, promotes human lung carcinogenesis. Oncogene 2010;29:635–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tessema M, Yingling CM, Thomas CL, et al. SULF2 methylation is prognostic for lung cancer survival and increases sensitivity to topoisomerase-I inhibitors via induction of ISG15. Oncogene 2012;31:4107–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual 7th edn. Springer, 2010:129–44 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai J, Chien J, Staub J, et al. Loss of HSulf-1 up-regulates heparin-binding growth factor signaling in cancer. J Biol Chem 2003;278:23107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai JP, Chien JR, Moser DR, et al. HSulf1 Sulfatase promotes apoptosis of hepatocellular cancer cells by decreasing heparin-binding growth factor signaling. Gastroenterology 2004;126:231–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Y, Yang Y, MacLeod V, et al. HSulf-1 and HSulf-2 are potent inhibitors of myeloma tumor growth in vivo. J Biol Chem 2005;280:40066–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Kleeff J, Abiatari I, et al. Enhanced levels of Hsulf-1 interfere with heparin-binding growth factor signaling in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer 2005;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grigoriadis A, Mackay A, Reis-Filho JS, et al. Establishment of the epithelial-specific transcriptome of normal and malignant human breast cells based on MPSS and array expression data. Breast Cancer Res 2006;8:R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo Y, Ogawa I, Kitajima S, et al. Periostin promotes invasion and anchorage-independent growth in the metastatic process of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 2006;66:6928–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro NP, Osorio CA, Torres C, et al. Evidence that molecular changes in cells occur before morphological alterations during the progression of breast ductal carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res 2008;10:R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson FK, Brodd J, Eklof C, et al. Identification of candidate cancer-causing genes in mouse brain tumors by retroviral tagging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:11334–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 2006;314:268–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holst CR, Bou-Reslan H, Gore BB, et al. Secreted sulfatases Sulf1 and Sulf2 have overlapping yet essential roles in mouse neonatal survival. PLoS One 2007;2:e575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.