Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of the study was to estimate health expectancy for the Palestinian population and to evaluate changes that have taken place over the past 5 years.

Design

Mortality data and population-based health surveys.

Setting

The Israeli-occupied Palestinian territory of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

Participants

17 034 and 38 071 adults aged 20 or over participating the Palestinian Family Health Surveys of 2006 and 2010. Death rates for 2007 and 2010 covered the entire population.

Outcome measures

Life expectancy and expected lifetime with and without chronic disease were estimated using the Sullivan method on the basis of mortality data and data on the prevalence of chronic disease.

Results

Life expectancy at the age of 20 increased from 52.8 years in 2006 to 53.3 years in 2010 for men and from 55.1 years to 55.7 years for women. In 2006, expected lifetime without a chronic disease was 37.7 (95% CI 37.0 to 38.3) years and 32.5 (95% CI 31.9 to 33.2) years for 20-year-old men and women, respectively. By 2010, this had decreased by 1.6 years for men and increased by 1.3 years for women. The health status of men has worsened. In particular, lifetime with hypertension and diabetes has increased. For women, the gain in life expectancy consisted partly of years with and partly of years without the most prevalent diseases.

Conclusions

Health expectancy for men and women diverged, which could to some extent be due to gender-specific exposures related to lifestyle factors and the impact of military occupation.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health, Health expectancy

Article summary.

Article focus

Health expectancy divides life expectancy into average lifetime in various states of health.

The concept of health expectancy has attracted increased interest among researchers and policymakers as a summary measure of population health and has been estimated in nearly all European countries as well as in many other countries worldwide but has never been estimated for a Middle Eastern population.

The study presents expected lifetime with and without chronic disease as well as what changes have taken place among Palestinians living in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territory over the past 5 years.

Key messages

Expected lifetime with the four most prevalent chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, heart diseases and rheumatic conditions) have increased for men. For women, the gain in life expectancy was more evenly distributed as years with and without diseases.

The divergent trends for men and women might be due to different exposures to lifestyle-related risk factors (eg, smoking) and the impact of military occupation.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The household response rates of the Palestinian Family Health Surveys of 2006 and 2010 were 88.0% and 89.4% and included information on 17 034 and 38 071 adult participants, respectively.

In spite of difficulties related to data collection under military occupation representativeness and high quality of the survey data were ensured. International organisations contributed with technical assistance.

Introduction

The number of Palestinians worldwide recently reached 11 million. Fewer than half (4.2 million) live in the occupied Palestinian territory. Of these, two million are refugees, the majority living in camps.1 As only 1.3 million Palestinians live in Israel, 5.5 million of the Palestinian population live abroad. The total area of historical Palestine is 27 000 km2. Six per cent of this was controlled by Jewish immigrants prior to the United Nations (UN) resolution on the partition of Palestine in 1947. Today, Israel controls 85% of the total area of historical Palestine. The Gaza Strip is one of the most densely populated parts of the World, with about 4300 individuals/km2.2 3 Continued land confiscation and intensified tightening of the closure system has increased the prevalence of economic crises, unemployment and poverty, thereby strengthening dependency on donor financing.4 Restrictions on freedom of movement, trading, employment, living a healthy life, access to healthcare, etc threaten welfare and public health.5–7

In 2010, the share of the population under the age of 20 in the occupied Palestinian territory was 53.3%, with 4.4% of the population being aged 60 years or older.8 According to WHO EMRO, the crude birth rate was 31 births per 1000 persons in 2010, and the crude death rate was 2.7 deaths per 1000 persons.9 In 2009, life expectancy at birth was 70.5 years for men and 73.2 for women.10 The six leading causes of death are heart disease (21.0% of all deaths), cerebrovascular disease (11.0%), cancer (10.3%), conditions in perinatal period (8.6%), respiratory disorders (6.9%) and accidents (5.4%).11

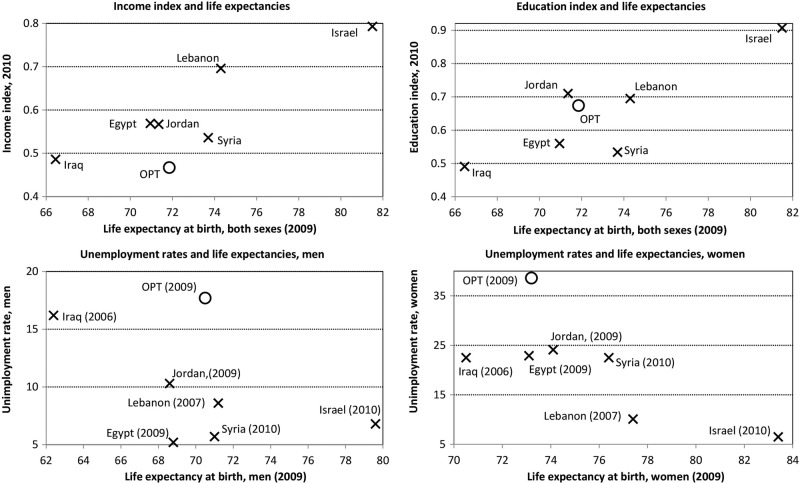

Figure 1 depicts the associations between selected structural indicators (income index, education index and unemployment rate) and life expectancy in some Middle East countries from data assessed by UNDP International Human Development Indicators,12 UN Statistics Division—Demographic and Social Statistics13 and WHO, Global Health Observatory Data Repository.10 Iraq and Israel represent the extremes. Life expectancy for Palestinian men is close to that of the male populations of Syrian Arab Republic and Lebanon. For Palestinian women life expectancy is low and close to that of Egyptian women. It appears clearly that in particular low-income level and high prevalence of unemployment retard the development in the occupied Palestinian territory.

Figure 1.

Income index, education index and unemployment rates by contrast with life expectancy in selected Middle East countries.

Health expectancy represents the average lifetime a person can expect to live in a specific state of health (eg, with or without chronic disease). As a summary measure of population health that combines health status and mortality, health expectancy has the strength of offering a more nuanced contribution to the monitoring of population health than do measurements of life expectancy. Health expectancy can be measured in various ways and for different population groups, that is, based on a geographical area, a social group or a group with other characteristics. The purpose of this study was to estimate expected lifetime with or without chronic disease among Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank and to evaluate changes that have taken place over the past 5 years.

Methods

Health prevalence data were derived from the Palestinian Family Health Surveys carried out in 2006 and 2010.8 14 The surveys were designed to be representative of the entire Palestinian population of the occupied Palestinian territory (ie, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem). The half-million Israelis living in illegal settlements on the West Bank and the more than five million exiled Palestinians were not represented in this study.

For each survey, a stratified two-stage random sample was drawn from lists of all Palestinian households. First, enumeration areas were selected from the Palestinian territories, then a random sample of households was drawn from each enumeration area in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The surveys consisted of 13 238 households in 2006 and 15 355 households in 2010. The household response rates were 88% in 2006 and 89.4% in 2010. Only in a subsample (7056 households) of the 2006 survey questions on chronic diseases were asked and the present study included adults aged 20 or above from the two surveys: 17 034 and 38 071 participants, respectively. Information on household members’ socioeconomic and demographic characteristics was provided by the head of household or another mature person. Data for all members were collected by self-reported responses or by proxy. Age was assessed by asking for the exact date of birth or any document with this information. Further details are available in the survey reports.8 14

Chronic disease was measured by answers to the question ‘Does (name) have any disease according to a medical diagnosis and receive treatment continuously?’ Whenever disease was reported, its nature was determined by choosing among 20 diseases. According to data from the Palestinian Family Survey of 2010,8 the four most frequently reported diseases were hypertension, diabetes, rheumatic condition and heart disease. The crude prevalence proportions among adults (aged 20 and above) were 8.5%, 6.5%, 4.9% and 2.7%, respectively in 2010.

In preparation for constructing life tables child and infant death rates at the age of 0–4 years were estimated on the basis of data from the Palestinian Family Health Surveys, and abridged life tables were constructed using MortPak, the UN demographic measurement software package.15

Health expectancy at the age of 20 was estimated using the Sullivan method16 17 in which the expected number of years lived in the age intervals of 20–24, 25–29, …, 70–74, >75 years were calculated on the basis of the life table figures and multiplied by age-specific proportions of healthy people taken from the health survey data. Health expectancy for 20-year-olds was then calculated by adding these years for all age groups and dividing the sum by the number of survivors at the age of 20. A measure of the portion of lifetime spent in good health was obtained by dividing lifetime in a healthy state with life expectancy. Furthermore, estimations were made of partial life expectancy, that is, expected lifetime between the ages of 20 and 60. Statistical tests were carried out using a Z test.17

A technique for decomposing health expectancies based on the Sullivan method enables comparisons over time of contributions to mortality differences and health differences.18 A change in age-specific mortality will change life expectancy because a greater or lesser number of years lived affects not only the specific age group but also the years lived in future older age groups. This change (the mortality effect) will increase or reduce expected lifetime in different health states. A change in the proportion of healthy people represents the decomposition's other component (the health effect).

Results

Life expectancy at the age of 20 was about half a year longer among men living in the West Bank than it was in the Gaza Strip and increased by half a year from 2006 to 2010 (table 1). For women, life expectancy increased by a little more than half a year, and the difference between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip remained nearly 1 year (table 2). For 60-year-olds, life expectancy increased by 0.2 years in the West Bank and by 0.3 years in the Gaza Strip.

Table 1.

Life expectancy at age 20 and 60, partial-life expectancy (age 20–60), and expected lifetime without and with chronic disease and proportion of expected lifetime without chronic disease—Men, Palestine, 2006 and 2010

| Calendar year | Life expectancy | Expected lifetime without chronic disease | Expected lifetime with chronic disease | Proportion of expected lifetime without chronic disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Years (95% CI) | Years (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| 20-year-old men | |||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 52.4 | 37.8 (36.7 to 38.9) | 14.6 (13.4 to 15.7) | 72.2 (70.0 to 74.4) |

| 2010 | 52.9 | 36.5 (35.7 to 37.2) | 16.4 (15.7 to 17.2) | 69.0 (67.5 to 70.4) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 52.9 | 37.6 (36.8 to 38.4) | 15.3 (14.5 to 16.1) | 71.0 (69.5 to 72.5) |

| 2010 | 53.5 | 36.0 (35.4 to 36.5) | 17.5 (17.0 to 18.0) | 67.3 (66.3 to 68.3) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 52.8 | 37.7 (37.0 to 38.3) | 15.1 (14.4 to 15.7) | 71.4 (70.2 to 72.7) |

| 2010 | 53.3 | 36.1 (35.7 to 36.6) | 17.1 (16.7 to 17.6) | 67.8 (67.0 to 68.7) | |

| 60-year-old men | |||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 16.9 | 7.6 (6.5 to 8.7) | 9.4 (8.3 to 10.5) | 44.6 (38.1 to 51.2) |

| 2010 | 17.2 | 6.1 (5.3 to 6.8) | 11.1 (10.3 to 11.8) | 35.4 (31.1 to 39.7) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 17.2 | 7.5 (6.7 to 8.2) | 9.7 (9.0 to 10.4) | 43.5 (39.1 to 47.8) |

| 2010 | 17.4 | 6.0 (5.5 to 6.5) | 11.4 (10.9 to 11.9) | 34.3 (31.5 to 37.2) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 17.1 | 7.5 (6.9 to 8.1) | 9.6 (9.0 to 10.2) | 43.9 (40.3 to 47.5) |

| 2010 | 17.3 | 6.0 (5.6 to 6.4) | 11.3 (10.9 to 11.7) | 34.7 (32.3 to 37.0) | |

| Partial-life expectancy between age 20 and 60 | |||||

| 20-year-old men | |||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 38.2 | 31.5 (30.8 to 32.1) | 6.7 (6.0 to 7.4) | 82.4 (80.7 to 84.2) |

| 2010 | 38.3 | 31.3 (30.9 to 31.8) | 7.0 (6.6 to 7.4) | 81.7 (80.6 to 82.9) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 38.3 | 31.2 (30.8 to 31.7) | 7.1 (6.6 to 7.6) | 81.5 (80.3 to 82.8) |

| 2010 | 38.5 | 30.8 (30.5 to 31.2) | 7.7 (7.3 to 8.0) | 80.1 (79.3 to 81.0) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 38.3 | 31.3 (30.9 to 31.7) | 7.0 (6.6 to 7.3) | 81.8 (80.8 to 82.8) |

| 2010 | 38.4 | 31.0 (30.7 to 31.3) | 7.4 (7.2 to 7.7) | 80.7 (80.0 to 81.3) | |

Table 2.

Life expectancy at age 20 and 60, partial life expectancy (age 20–60), and expected lifetime without and with chronic disease and proportion of expected lifetime without chronic disease—Women, Palestine, 2006 and 2010

| Calendar year | Life expectancy | Expected lifetime without chronic disease | Expected lifetime with chronic disease | Proportion of expected lifetime without chronic disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Years (95% CI) | Years (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| 20-year-old women | |||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 54.5 | 34.4 (33.3 to 35.5) | 20.1 (19.0 to 21.2) | 63.1 (61.1 to 65.2) |

| 2010 | 55.2 | 34.9 (34.2 to 35.7) | 20.3 (19.5 to 21.0) | 63.2 (61.9 to 64.6) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 55.4 | 31.6 (30.8 to 32.4) | 23.8 (23.0 to 24.6) | 57.1 (55.6 to 58.5) |

| 2010 | 56.0 | 33.2 (32.7 to 33.7) | 22.8 (22.2 to 23.3) | 59.3 (58.4 to 60.2) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 55.1 | 32.5 (31.9 to 33.2) | 22.5 (21.9 to 23.2) | 59.1 (57.9 to 60.2) |

| 2010 | 55.7 | 33.8 (33.3 to 34.2) | 21.9 (21.5 to 22.4) | 60.6 (59.9 to 61.4) | |

| 60-year-old women | |||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 18.5 | 5.7 (4.7 to 6.6) | 12.8 (11.8 to 13.8) | 30.6 (25.3 to 35.9) |

| 2010 | 18.8 | 5.2 (4.6 to 5.9) | 13.6 (12.9 to 14.2) | 27.9 (24.4 to 31.4) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 18.9 | 5.0 (4.3 to 5.6) | 13.9 (13.3 to 14.6) | 26.3 (22.9 to 29.7) |

| 2010 | 19.2 | 4.4 (4.0 to 4.8) | 14.8 (14.3 to 15.2) | 22.9 (20.7 to 25.2) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 18.8 | 5.2 (4.6 to 5.7) | 13.6 (13.0 to 14.1) | 27.6 (24.7 to 30.5) |

| 2010 | 19.0 | 4.7 (4.3 to 5.0) | 14.4 (14.0 to 14.7) | 24.5 (22.6 to 26.4) | |

| Partial-life expectancy between age 20 and 60 | |||||

| 20 year-old women | |||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 38.4 | 29.5 (28.8 to 30.2) | 8.9 (8.2 to 9.7) | 76.7 (74.9 to 78.6) |

| 2010 | 38.6 | 30.3 (29.8 to 30.8) | 8.3 (7.9 to 8.8) | 78.4 (77.2 to 79.6) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 38.7 | 27.2 (26.7 to 27.7) | 11.5 (10.9 to 12.0) | 70.4 (69.0 to 71.7) |

| 2010 | 38.8 | 29.3 (28.9 to 29.6) | 9.6 (9.2 to 9.9) | 75.4 (74.5 to 76.3) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 38.6 | 28.0 (27.6 to 28.4) | 10.6 (10.2 to 11.0) | 72.5 (71.4 to 73.6) |

| 2010 | 38.7 | 29.6 (29.3 to 29.9) | 9.1 (8.9 to 9.4) | 76.4 (75.7 to 77.1) | |

During this period, expected lifetime without chronic disease at the age of 20 decreased statistically significantly by 1.6 years for men in the West Bank (p=0.02) and statistically insignificantly by 1.3 years in the Gaza Strip (p=0.17; table 1). Simultaneously, expected lifetime with chronic disease among male Palestinians increased significantly by approximately 2 years (p<0.001). Partial-life expectancy between the ages of 20 and 60 with chronic disease increased from 7 years in 2006 to 7.4 years in 2010 (table 1). Among 60-year-old men, expected lifetime with chronic disease increased by 1.7 years. The proportion of expected lifetime without chronic disease between the ages of 20 and 60 declined from 81.8% to 80.7% and from 43.9% to 34.7% for 60-year-olds (table 1). This change does not differ between the West bank and the Gaza Strip.

For 20-year-old women living in the West Bank, expected lifetime without chronic disease increased statistically significantly by 1.6 years (p=0.02; table 2). The gain in disease-free life expectancy thus exceeded the increase in life expectancy. In the Gaza Strip, the gain of 0.7 years in life expectancy among 20-year-old women was evenly distributed, with 0.5 years without disease and 0.2 years with disease (table 2). For Palestinian women between ages of 20 and 60, expected years with chronic disease decreased from 10.6 to 9.1 during the period of 2006–2010 (table 2). The general gain in disease-free life expectancy did not, however, favour elderly Palestinian women. Thus, among 60-year-old women, expected lifetime with chronic disease increased by 0.8 years (table 2).

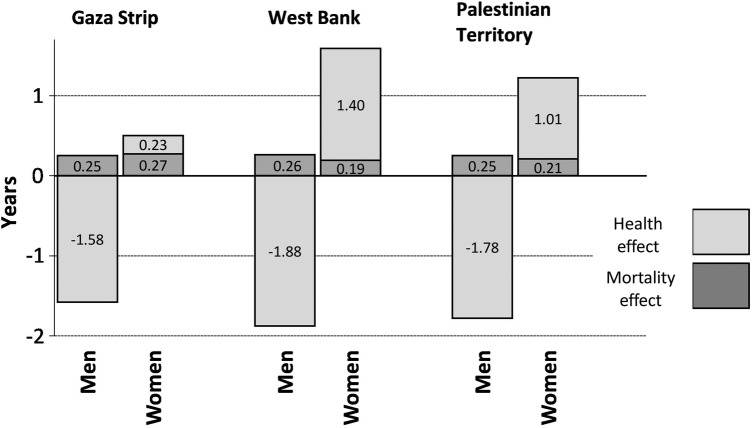

Figure 2 shows the results of decomposing into mortality and health effects the change over time in disease-free life expectancy at the age of 20. The mortality effect of approximately one-fourth of a year was nearly equal for men and women and did not differ between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. The divergent change from 2006 to 2010 between men and women in expected lifetime without chronic disease thus resulted from the health effect (ie, prevalence of disease increased among men and decreased among women).

Figure 2.

Decomposition into the mortality and health effects of changes between 2006 and 2010 in disease-free life expectancy at age 20 in the occupied Palestinian territory.

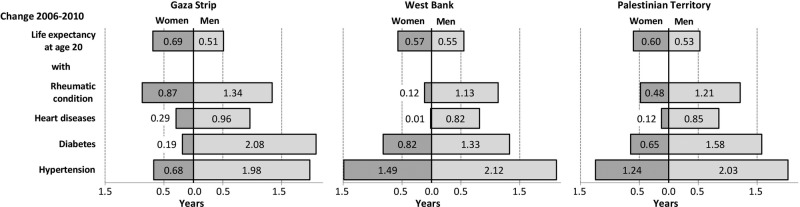

In 2010, 20-year-old men and women could expect 3.6 years (95% CI 3.3 to 3.9) and 3.2 years (95% CI 3.0 to 3.5) with heart disease, respectively. For the three other most prevalent chronic conditions, women could expect a greater number of years with a disease than could men (12.5 vs 7.7 years with hypertension, 8.3 vs 6.7 years with diabetes and 6.8 vs 3.6 years with rheumatic conditions; table 3). No gain in disease-free life expectancy was observed for any of the four diseases, with the exception of heart disease among women. In particular, the health status of men worsened, and the gender gap decreased during the period 2006–2010 (table 3; figure 3).

Table 3.

Life expectancy at age 20 and expected lifetime with the four most prevalent diseases—Palestine, 2006 and 2010

| Expected lifetime with |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calendar year | Life expectancy years | Hypertension years (95% CI) | Diabetes years (95% CI) | Heart diseases years (95% CI) | Rheumatic conditions years (95% CI) | |

| 20-year-old men | ||||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 52.4 | 6.0 (5.1 to 6.8) | 4.6 (3.9 to 5.4) | 2.4 (1.8 to 2.9) | 2.1 (1.5 to 2.7) |

| 2010 | 52.9 | 7.9 (7.2 to 8.6) | 6.7 (6.0 to 7.4) | 3.3 (2.8 to 3.8) | 3.4 (2.9 to 4.0) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 52.9 | 5.5 (4.9 to 6.1) | 5.4 (4.8 to 6.0) | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.3) | 2.5 (2.1 to 3.0) |

| 2010 | 53.5 | 7.6 (7.2 to 8.1) | 6.8 (6.3 to 7.2) | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.1) | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.0) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 52.8 | 5.7 (5.2 to 6.2) | 5.1 (4.7 to 5.6) | 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1) | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.7) |

| 2010 | 53.3 | 7.7 (7.3 to 8.1) | 6.7 (6.3 to 7.1) | 3.6 (3.3 to 3.9) | 3.6 (3.3 to 3.9) | |

| 20-year-old women | ||||||

| Gaza Strip | 2006 | 54.5 | 11.8 (10.8 to 12.8) | 7.9 (7.0 to 8.8) | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.0) | 4.1 (3.4 to 4.8) |

| 2010 | 55.2 | 12.5 (11.7 to 13.2) | 8.1 (7.4 to 8.7) | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.2) | 5.0 (4.4 to 5.6) | |

| West Bank | 2006 | 55.4 | 10.9 (10.2 to 11.7) | 7.5 (6.9 to 8.2) | 3.5 (3.0 to 4.0) | 7.6 (7.0 to 8.3) |

| 2010 | 56.0 | 12.4 (11.9 to 13.0) | 8.4 (7.9 to 8.8) | 3.5 (3.1 to 3.9) | 7.8 (7.3 to 8.2) | |

| Palestinian Territory | 2006 | 55.1 | 11.2 (10.6 to 11.8) | 7.6 (7.1 to 8.1) | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.5) | 6.4 (5.9 to 6.9) |

| 2010 | 55.7 | 12.5 (12.0 to 12.9) | 8.3 (7.9 to 8.7) | 3.2 (3.0 to 3.5) | 6.8 (6.5 to 7.2) | |

Figure 3.

Change between 2006 and 2010 in life expectancy and expected lifetime at age 20 with the four most frequent chronic diseases in the occupied Palestinian territories.

Discussion

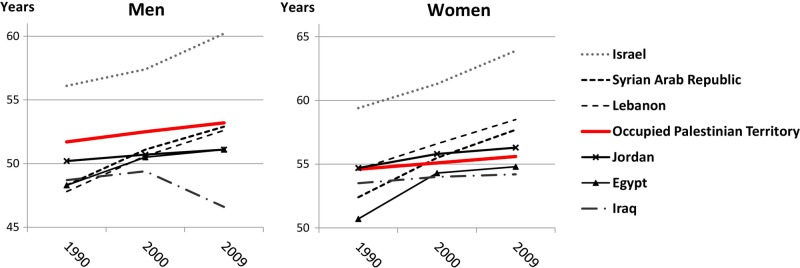

As in other populations, Palestinian women live longer than Palestinian men and endure a greater number of years with health problems. But Palestinian women's advantage of 2.7 more years of expected lifetime in 2009 is much less than the gender difference in the neighbouring populations. During the last 20 years, life expectancy has increased more for Palestinian men than women, but for both genders the increase has generally been slower for Palestinians than for the neighbouring populations (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Life expectancy at age 20 in the occupied Palestinian territory and other Middle East countries. Sources: WHO, Global Health Observatory Data Repository and Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

Remarkably, the changes in partial-life expectancy (age interval 20–60) without chronic disease from 2006 to 2010 went in opposite directions for men and women. At age 60, lifetime without chronic disease decreased for both sexes, but more among men than women. Health has thus worsened among men, and the gender gap in expected lifetime with chronic disease has narrowed. The changes in health expectancy between 2006 and 2010 were mainly due to the increasing prevalence of chronic disease and not due to increasing life expectancy (figure 2). The gain in life expectancy for men thus consisted not only of additional years with hypertension, diabetes, heart disease and rheumatic conditions because expected lifetime without these diseases was shorter in 2010 than in 2006. This tendency towards expansion of morbidity was less distinct for women.

The increase in lifetime with hypertension and diabetes among men is particularly worrisome, although it might partly reflect trends in ascertainment. Hypertension and diabetes are initial stages of cardiovascular disease, and the risk is elevated because of the high prevalence of tobacco smoking among men. The percentage of smoking among men exceeds 40% but is less than 3% among women.8 19 The prevalence of smoking is significantly higher in the West Bank than the Gaza Strip. The percentage of smokers aged 18 and over has declined from 29.2% in 2000 to 26.9% in 2010 in the West Bank and from 24.1% to 14.6 in the Gaza Strip.8 Lung cancer is the most frequent cancer type among Palestinian men.11 In general, chronic disease develops gradually, caused by exposure to risk factors such as the effects of psychological stressors or the long-term cumulative effects of tobacco smoking. Poor nutrition or undernourishment, in particular in the Gaza Strip and during childhood, increases the risk of obesity and chronic disease.11 20–22 Along with tobacco smoking among men, poor nutrition and physical inactivity are the most important preventable lifestyle-related risk factors for Palestinians. Prevention related to these risk factors requires particular attention in order to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular and metabolic disease.

Men—particularly young men—face greater exposure to violations by the Israeli army and Israeli settlers than do women.23–26 Since 1967, an unknown number of Palestinians, mostly young men, have been imprisoned on political grounds and have suffered various health problems following their release.27 28 The fluctuations and instability of Palestinians’ societal and political life could affect men and women differently. A survey among young Palestinians in Ramallah showed that exposure to political violence affects the mental health of adolescents and that depressive-like symptoms were more prevalent among girls than among boys.29

Health services and access to diagnosis and treatment are complicated in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip due to a variety of factors related to restrictions on movement in the West Bank and the blockade that cuts the Gaza Strip off from the outside world.5 30 Some of these deficiencies are, however, partially remedied by humanitarian aid from international bodies. As the character of the abnormal living circumstances differs between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, no simple interpretation can be applied to differences between the two territories. The economic hardship can be illustrated by the high unemployment rates. According to the Palestinian National Authority the unemployment rates in 2011 were 15.9% and 22.6% for men and women in the West Bank and 25.8% and 44% in the Gaza Strip.31

In spite of the high number of deaths, attacks on medical personnel and civilians, destruction of hospitals, etc32 associated with the Israeli assault on the Gaza Strip shortly before the second survey in 2010, we cannot expect that this assault would be directly visible in the health expectancy estimates. The direct effect of Israeli attacks should be assessed by studies with a more focused design, such as on the impact of the Israeli attack on the Gaza Strip,32–36 the Israeli military invasions in the spring of 2002,29 37 and the army's reaction to the 2000 uprising.25

In 2009, the Lancet published a series of comprehensive studies on the health status of the population and the health services available in the occupied Palestinian territory, providing complete information on and evidence of the situation.5 6 11 30 38 The unsuccessful attempt to establish an efficient healthcare system under military occupation has also been examined.30 Health status has not improved satisfactorily since the mid-1990s, and the health services have remained in stasis.30

Account has been taken of logistical difficulties related to data collection under military occupation and how this may influence participation and responses by interviewees. The quality of the survey data is high due to a thoroughly centralised interview training process, pilot testing and the quality-control mechanisms applied to data processing. The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics received technical assistance from international organisations (UNICEF, UN Population Fund and the Arab League). Furthermore, the standardisation of questionnaires and sampling methods enables comparisons over time. Study design, representativeness, non-participation, etc in the Palestinian Family Health Surveys have been described previously in reports by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.8 14

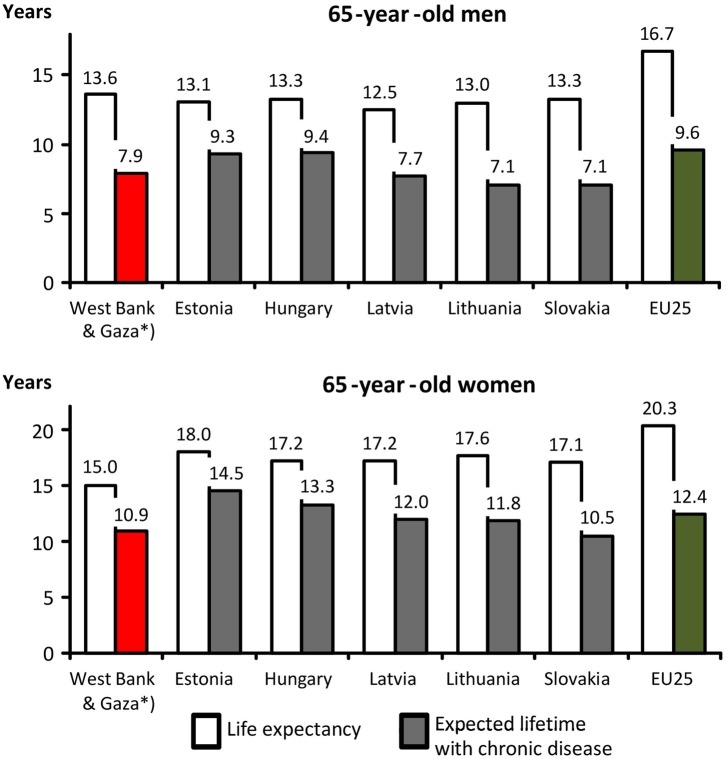

Over half of the Palestinian population is between the ages of 0 and 19, and less than 5% is over 60 years of age. Thus, we did not estimate the widely used disability-free life expectancy indicator that is typically based on questions related to ageing such as functional disability in activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living. The Minimum European Health Module includes a question on chronic conditions: ‘Do you suffer from any long-standing illness or condition (health problem)?’39 Health expectancy estimates based on this question are available for European countries.40 Among the 25 EU member states in 2005 life expectancy at age 65 varied from 12.5 to 17.7 years for men and from 17.1 to 22.0 years for women. The average expected lifetime without chronic morbidity was estimated at 9.6 years for 65-year-old men and 12.4 years for 65-year-old women.40 In general life expectancy was lowest in East European countries. While uniformly constructed life tables make international comparisons of life expectancy possible it is a challenge to compare health expectancies. Due to the lack of international harmonised questionnaires including chronic disease questions we still need comparable data on health expectancy. However, figure 5 presents expected lifetime with chronic disease for 65-year-old Estonians, Hungarians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Slovakians and the whole Europe (EU25) in 200540 and Palestinians in 2006. Because the wording of the questions on chronic diseases in the Minimum European Health Module and in the Palestinian Family Health Survey 2006 differs it is unwise to attribute much weight to the comparison of expected lifetime with chronic disease between the European countries and the occupied Palestinian territory.

Figure 5.

Life expectancy and expected lifetime with chronic disease* at age 65 in selected European countries, the whole European Union and the occupied Palestinian territory. *) Different questions on chronic diseases in the Minimum European Health Module and the Palestinian Family Health Survey (see text).

There was a striking different gender gap in life expectancy between Europeans and Palestinians (figure 5). Among 65-year-old Palestinians the women's life expectancy was only 10% longer than men's whereas the gap in the East European countries varied between 28% and 35%. The average gap in EU25 was 22%. The different gender gap in life expectancy and health expectancy between the more established EU countries and the newer EU countries has been discussed previously.41 42

Because the study describes health expectancy after the age of 20, less than half of the population is presented. Demography in the occupied Palestinian territory requires great attention to the health and welfare of Palestinian children and adolescents.

The occupied Palestinian territory is well supplied by data from health surveys, which could help strengthen the health information system. We recommend that health expectancy be introduced as a summary measure of population health for monitoring the health status in Palestine. The data necessary for introducing this indicator are available by conducting successive uniformly designed health surveys. Coordination with and the simultaneity of the Pan Arab Project for Family Health furthermore enables future comparisons of health expectancy between populations in the Arab countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Results for 2006 were presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of REVES, International Network on Health Expectancy, 25–27 May 2011, Paris, France. Travelling expenses for KQ were covered by a grant supporting the REVES meeting.

Footnotes

Contributors: KQ and HBH initiated the study. KQ and MD provided life tables and health status prevalence tables. HBH undertook the analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the writing of the manuscript and have seen and approved the final version.

Funding: Grant at University of Southern Denmark for establishing international research collaboration.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sources were derived from the Palestinian Family Health Surveys carried out in 2006 and 2010: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Palestinian Family Health Survey, 2006: Final report. Ramallah, 2007. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1416.pdf Palestinian National Authority, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Palestinian Family Survey, 2010, Main Report, Ramallah, 2011. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1821.pdf

References

- 1.UNRWA Statistics-2010 Selected Indicators. United Nation Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, 2011. http://www.unrwa.org/userfiles/2011120434013.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 2.Statistical yearbook of Palestine 2011 Palestinian National Authority, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Ramallah, 2011. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1814.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 3.Special Statistical Bulletin on the 63rd anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Ramallah, 2011. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_pcbs/PressRelease/Nakba_E63.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 4.World Bank Towards a Palestinian State: Reforms for Fiscal Strengthening. World Bank, 2010. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWESTBANKGAZA/Resources/WorldBankReportAHLCApril2010Final.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 5.Giacaman R, Khatib R, Shabaneh L, et al. Health status and health services in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009;373:837–49 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batniji R, Rabaia Y, Nguyen-Gillham V, et al. Health as human security in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009;373:1133–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rytter MJH, Kjældgaard A-L, Brønnum-Hansen H, et al. Effects of armed conflict on access to emergency health care in Palestinian West Bank: systematic collection of data in emergency departments. BMJ 2006;332:1122–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palestinian National Authority, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Palestinian Family Survey, 2010, Main Report, Ramallah, 2011. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1821.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 9.World Health Organisation, Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office http://rho.emro.who.int/rhodata/?theme=country&vid=21500# (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 10.World Health Organisation, Global Health Observatory Data Repository http://apps.who.int/ghodata/?vid=720 (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 11.Husseini A, Abu-Rmeileh NME, Mikki N, et al. Cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and cancer in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009;373:1041–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNDP International Human Development Indicators. http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/tables (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 13.UN Statistics Division—Demographic and Social Statistics. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 14.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Palestinian Family Health Survey, 2006: Final report. Ramallah, 2007. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1416.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 15.MORTPAK for Windows The United Nations Software Package for Demographic Measurement. Developed by the United Nations Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/mortpak/MORTPAKwebpage.pdf (accessed 7 Sep2012).

- 16.Sullivan DF. A single index of mortality and morbidity. Health Services and Mental Health Administration (HSMHA). Health Rep 1971;86:347–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagger C, Cox B, Roy SL, et al. Health expectancy calculation by the Sullivan method: A practical guide, 3rd Edition. EHEMU Technical report 2006_3, 2007. http://www.eurohex.eu/pdf/Sullivan_guide_final_jun2007.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 18.Nusselder WJ, Looman CW. Decomposition of differences in health expectancy by cause. Demography 2004;41:315–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Rmeileh NME, Alderete E, Duque LF, et al. Smoking among adolescents and teenagers living under conflict: cross-sectional surveys in three settings. TheLancet.com Published online July 5, 2011. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/palestine2011-9.pdf (accessed Sep 7, 2012).

- 20.Nasser K, Awartani F, Hasan J. Nutritional status in Palestinian schoolchildren living in West Bank and Gaza Strip: a cross-sectional survey. TheLancet.com Published online July 2, 2010. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/S0140673610608136.pdf (accessed Sep 7, 2012).

- 21.Mikki N, Abdul-Rahim HF, Awartani F, et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of stunting, underweight, and overweight among Palestinian school adolescents (13–15 years) in two major governorates in the West Bank. BMC Public Health 2009;9:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikki N, Abdul-Rahim HF, Shi Z, et al. Dietary habits of Palestinian adolescents in three major govenorates in the West Bank: a cross-sectional survey. TheLancet.com Published online July 2, 2010. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/S0140673610608483.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 23.Halileh SO. Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Need for medical services for Palestinians injured in West Bank is urgent. BMJ 2002;324:361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferriman A. Palestinian territories face huge burden of disability. BMJ 2002;324:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helweg-Larsen K, Al-Qadi AHAJ, Al-Jabriri J, et al. Systematic medical data collection of intentional injuries during armed conflicts: a pilot study conducted in West Bank, Palestine. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghuneim NI, Abed Y. Effects of non-fatal injuries during the war on Gaza Strip on quality of life: a cross-sectional study. TheLancet.com Published online July 2, 2010. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/S0140673610608458.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 27.Nashif E. Palestinian Political Prisoners: Identity and Community. New York: Routledge, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Sarraj E, Punamaki RL, Salmi S, et al. Experience of torture and ill-treatment and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Palestinian political prisoners. J Trauma Stress 1996;9:595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giacaman R, Shannon HS, Saab H, et al. Individual and collective exposure to political violence: Palestinian adolescents coping with conflict. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:361–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mataria A, Khatib R, Donaldson C, et al. The health-care system: an assessment and reform agenda. Lancet 2009;373:1207–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palestinian National Authority http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/881/draft.aspx (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 32.Marton R. Human rights violations during Israel's attack on the Gaza Strip: 27 December 2008 to 19 January 2009. Glob Public Health 2011;6:560–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abu-Rmeileh NME, Hammoudeh W, Giacaman R. Humanitarian crisis and social suffering in Gaza Strip: an initial analysis of aftermath of latest Israeli war. TheLancet.com Published online July 2, 2010. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/S014067361060846X.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 34.Ashour M, Ghuneim N, Yaghi A. Civilians’ experience in the Gaza Strip during the Operation Cast Lead by Israel. TheLancet.com Published online July 5, 2011. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/palestine2011-1.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 35.Ziadni M, Hammoudeh W, Abu-Rmeileh NME, et al. Human insecurity and associated factors in the Gaza Strip 6 months after 2008–09 Israeli attack: a cross-sectional survey. TheLancet.com Published online July 5, 2011. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/palestine2011-2.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 36.Abu-Rmeileh NME, Hammoudeh W, Mataria A, et al. Health-related Quality of life of Gaza Palestinians in the aftermath of the winter 2008–09 Israeli attack on the strip. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:732–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giacaman R, Husseini A, Gordon NH, et al. Imprints on the consciousness. The impact on Palestinian civilians of the Israeli Army invasion of West Bank towns. Eur J Public Health 2004;14:286–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahim HFA, Wick L, Halileh S, et al. Maternal and child health in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009;373:967–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cox B, Van Oyen H, Cambois E, et al. The reliability of the Minimum European Health Module. Int J Public Health 2009;54:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jagger C, Robine J-M, Van Oyen H, et al. Life Expectancy with Chronic Morbidity. In Healthy Life Years in the European Union: Facts and figures 2005. Directorate-General for Health & Consumers, European Communities, 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_information/reporting/docs/hly_en.pdf (accessed 7 Sep 2012).

- 41.Nusselder WJ, Looman CWN, Van Oyen H, et al. Gender differences in health of EU10 and EU15 populations: the double burden of EU men. Eur J Ageing 2010;7:219–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Oyen H, Cox B, Jagger C, et al. Gender gap in life expectancy and expected years with activity limitations of age 50 in the European Union: associations with macro-level structural indicators. Eur J Ageing 2010;7:229–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.