Abstract

Objectives

We examined the potential association between prior chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and edentulism, and whether the association varied by COPD severity using data from the Dental Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

Community dwelling subjects from four US communities.

Participants and measurements

Cases were identified as edentulous (without teeth) and subjects with one or more natural teeth were identified as dentate. COPD cases were defined by spirometry measurements that showed the ratio of forced expiratory volume (1 s) to vital capacity to be less than 0.7. The severity of COPD cases was also determined using a modified Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease classification criteria (GOLD stage I–IV). Multiple logistic regression was used to examine the association between COPD and edentulism, while adjusting for age, gender, centre/race, ethnicity, education level, income, diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease and congestive heart failure, body mass index, smoking, smokeless tobacco use and alcohol consumption.

Results

13 465 participants were included in this analysis (2087 edentulous; 11 378 dentate). Approximately 28.3% of edentulous participants had prior COPD compared with 19.6% among dentate participants (p<0.0001). After adjustment for potential confounders, we observed a 1.3 (1.08 to 1.62) and 2.5 (1.68 to 3.63) fold increased risk of edentulism among GOLD II and GOLD III/IV COPD, respectively, as compared with the non-COPD/dentate referent. Given the short period of time between the measurements of COPD (visit 2) and dentate status (visit 4) relative to the natural history of both diseases, neither temporality nor insight as to the directionality of the association can be ascertained.

Conclusions

We found a statistically significant association between prior COPD and edentulism, with evidence of a positive incremental effect seen with increasing GOLD classification.

Keywords: Pulmonary disease, Edentulism, Chronic Obstructive disease, bronchitis

Article summary.

Article focus

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a community-dwelling population of 13 465 participants enrolled in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC).

We searched for a potential association between edentulism and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) scoring levels for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Multiple logistic regression models were used to examine the association while adjusting for multiple covariates and confounders.

Key messages

We found a statistically significant association between edentulism (no teeth) and prior obstructive airway disease in fully adjusted models with incremental effects with increasing GOLD classification.

A similar association with periodontal disease severity and COPD among those with teeth (dentate) was also observed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a large representative population that includes African Americans that has full periodontal examination and respiratory function data.

A GOLD stage was determined by standardised lung function testing.

A limitation arises from the minor temporal discrepancy in the collection of the periodontal examination data and the respiratory function assessments.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently the fifth leading cause of death world-wide, and is expected to rise to fourth place in 2030.1 Although COPD has a heterogeneous clinical presentation primarily characterised by airflow limitation, generally associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs,2 it is also often associated with a significant systemic inflammatory response3 which has been correlated with adverse clinical effects.3 4

Over the past decade there has been an increased interest in the link between respiratory diseases and oral infection. Higher levels of tooth-associated microorganisms (plaque) and periodontal disease have been associated with COPD.5–7 Recently, in a very comprehensive oral microbiology study, high levels of diverse microbes—including several implicated in COPD and denture stomatitis—were identified on previously worn dentures.8 Thus, both the teeth and the dentures are non-desquamating oral surfaces that allow the oral biofilm to emerge eliciting periodontal disease or denture stomatitis, respectively. This raises the question as to whether denture-associated microbes may contribute to COPD in a manner analogous to periodontal organisms. Because oral infections and denture-based sources of sepsis are both treatable and preventable, the potential association of high microbial burden of oral origin to COPD may represent modifiable risk factors that may potentially improve respiratory-related morbidity. It has been suggested by Garcia et al7 that the observed association between oral health and COPD may be due to the aspiration of oral pathogens, or a common underlying host susceptibility trait that places individuals at risk for both conditions such as an exaggerated inflammatory response that is triggered by oral microbes.

Although numerous studies have examined the association between oral health and respiratory diseases in dentate individuals, the published literature are scant with respect to studies that have examined the association between edentulism and COPD status/severity. We undertook the current study to examine the potential association between COPD and edentulism using data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. We hypothesised that edentulism would be associated with a diagnosis of COPD and display a higher prevalence with spirometry categories of more pronounced COPD. These data include not only dentate status and full-mouth periodontal examination measurements, but also include results from direct pulmonary function tests and symptomology assessments that enabled classification of COPD severity.

Methods

We sought to test the hypothesis that the prevalence of edentulism was greater among individuals with a reported history of lung disease (ie, COPD) and that the association with edentulism varied by COPD severity as determined by a modified Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (GOLD) criteria. Our second hypothesis was that among dentate subjects there was a difference in the prevalence of periodontal disease according to the severity of COPD as measured by GOLD criteria.

Study population and study design

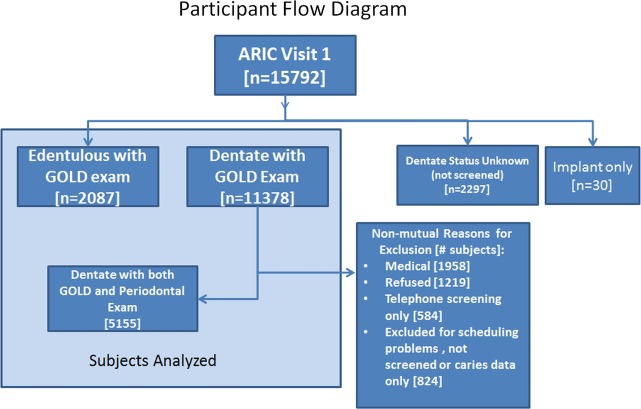

The entire cohort from the ARIC study was 15 792 and the available dental cohort Dental ARIC (D-ARIC) data were used to study participants with both a periodontal examination and completed spirometry data. The cohort selection process and reasons for exclusion appear in figure 1. Descriptions of the cohort and the periodontal examination procedure have been described previously.9 Eligible participants were all aged 45–64 at study entry (ie, visit 1) and had spirometry measurements at visit 2 (3 years later) and periodontal examinations at D-ARIC visit 4 (6 years from visit 2).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Case definitions

Edentulism case definitions were defined as study participants without any natural teeth or implants. Participants with one or more natural teeth (comprising 11 378 subjects) were selected as the dentate subjects. The absence, presence or severity of periodontal disease among dentate subjects was determined using the joint American Association of Periodontology/Center for Disease Control (AAP/CDC) consensus definitions of Health, Early and Advanced disease.10

This investigation represents the first report that uses actual pulmonary function data to assess lung function as an exposure related to edentulism or periodontal disease. The measured exposure of pulmonary function was classified both as a dichotomous (eg, COPD vs no COPD) and ordinal categorical variable (eg, no lung disease, restrictive disease, COPD GOLD stages I–IV), using the following criteria.

Airway obstruction

Dichotomous variable (COPD/no COPD)—prior airway obstruction (or COPD) was defined based on spirometry measurements collected during visit 2. Participants with a ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.7 were determined to have airway obstruction consistent with COPD.

Ordinal categorical variable (COPD GOLD stage)—severity of COPD was also examined in this study among COPD participants using a modification of the spirometry-based criteria for severity outlined in the GOLD guidelines.11 12

| GOLD stage | Spirometry criteria |

|---|---|

| No lung disease | FEV1/FVC≥0.7 and FEV1≥80% predicted |

| Restrictive disease | FEV1/FVC≥0.7 and FVC<80% predicted |

| Stage 0 | Presence of respiratory symptoms in the absence of any lung function abnormality; and no lung disease |

| Stage I | FEV1/FVC<0.7 and FEV1≥80% predicted |

| Stage II | FEV1/FVC<0.7 and 50%≤FEV1<80% predicted |

| Stage III | FEV1/FVC<0.7 and 30%≤FEV1<50% predicted |

| Stage IV | FEV1/FVC<0.7 and FEV1<30% predicted |

Variables of interest

Smoking data (both for cigarettes and cigars) collected during visit 4 were used to adjust for the confounding effect of smoking on the relationship between airway obstruction (COPD) and being edentulous. Smoking was treated as a five-level categorical variable, as described in detail previously.7 Cardiovascular disease comorbidities that may be associated with both history of airway obstruction and being edentulous were also examined using data from visit 4. Other potential confounders examined included race and examination centre, ethnicity, education level, income, frequency of dental visits, diabetes, body mass index, alcohol use and medication utilisation. These data were extracted from visit 4.

Data analysis

Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between COPD and edentulous status. This was followed by a logistic regression analysis of the dentate subjects comparing the COPD prevalence and severity of dentate patients without periodontal disease to that of dentate patients with periodontal disease. The exposure variable, which is airway obstruction, was examined as both a dichotomous variable (eg, positive prior COPD vs no COPD) and by logistic models using nominal variables (eg, no lung disease, restrictive disease, GOLD 0–IV) based on spirometry data collected as part of the ARIC examination. For the no COPD or GOLD reference group we included: subjects with and without chronic respiratory symptoms with no lung function abnormality and subjects with GOLD 0 and restrictive disease. Multiple regression models were used to control for confounding. When adjusting for potential confounding variables we included in certain models variables that are known to modify either periodontal disease status or COPD, including body mass index and smokeless tobacco. We developed minimally and fully adjusted logistical models incorporating significant confounders and effect modifiers to compute OR and 95% CI using SAS V.9.2 (Cary, North Carolina, USA). We also included traditional risk factors for edentulism, periodontal disease and COPD–such as age, even if not statistically significant in this cohort. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for this study.

Sample size and power calculations

We knew a priori that the ARIC cohort who had spirometry data from visit 2 included 2087 edentulous subjects, as determined by questionnaire data at visit 4. We also had 11 378 dentate subjects with spirometry data at visit 2, of which 5155 subjects had a full-mouth periodontal examinaton completed. Thus, if approximately 9% of the 13 465 subjects (2087 edentulous and 11 378 dentate) were determined to have COPD, we estimated that we had >99% power to detect a significant difference of 1% at p=0.05 in the prevalence of COPD when comparing edentulous versus dentate subjects.

Results

ARIC subject participation was based upon the inception cohort of 15 792 subjects. The visit 4 screenings were broadly divided into 11 378 dentate and 2 087 edentulous subjects who also had spirometry data. These subjects are used for analyses in tables 1–6 on the relationship between dentate status and COPD. Subjects were excluded (n=2327) from the original inception participants for incomplete data, dental implants only and missing visit 4 screening.

Table 1.

Dentate status by GOLD stage

| No chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality | Restrictive disease (FEV1/FVC≥0.7 and FVC<80% predicted) | GOLD 0 (chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality) | GOLD I | GOLD II | GOLD III/IV | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edentulous | 1294 (13.3%) | 151 (24.6%) | 51 (16.4%) | 208 (14.7%) | 290 (25.2%) | 93 (35.6%) | |

| Dentate | 8422 (86.7%) | 464 (75.5%) | 260 (83.6%) | 1204 (85.3%) | 860 (74.8%) | 168 (64.4%) | <0.0001 |

*χ2 test.

FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Table 2.

Demographics by GOLD stage

| GOLD reference* | GOLD I | GOLD II | GOLD III/IV | p Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edentulous | 1496 (14.1%) | 208 (14.7%) | 290 (25.2%) | 93 (35.6%) | |

| Dentate | 9146 (85.9%) | 1204 (85.3%) | 860 (74.8%) | 168 (64.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Race/centre | |||||

| MS African Americans | 2654 (25.1%) | 191 (13.6%) | 196 (17.1%) | 73 (28.4%) | |

| NC African Americans | 285 (2.7%) | 35 (2.5%) | 27 (2.4%) | 11 (4.3%) | |

| NC white | 2211 (20.9%) | 401 (28.5%) | 344 (30.0%) | 84 (32.7%) | |

| Washington Co, MD | 2680 (25.3%) | 350 (24.9%) | 337 (29.4%) | 56 (21.8%) | |

| Surburban minneapolis | 2747 (26.0%) | 430 (30.6%) | 243 (21.2%) | 33 (12.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 6344 (59.6%) | 684 (48.4%) | 457 (39.7%) | 125 (47.9%) | |

| Male | 4298 (40.4%) | 728 (51.6%) | 693 (60.3%) | 136 (52.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Mean age (SD) | 62.4 (5.59) | 64.2 (5.69) | 64.9 (5.57) | 64.2 (5.70) | <0.0001 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 29.2 (5.68) | 27.1 (4.81) | 27.6 (5.34) | 27.3 (6.16) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes (yes) | 1573 (17.4%) | 132 (10.8%) | 179 (19.7%) | 36 (20.7%) | |

| No | 7486 (82.6%) | 1090 (89.2%) | 732 (80.4%) | 138 (79.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (yes) | 3591 (39.4%) | 388 (31.9%) | 374 (40.7%) | 74 (41.8%) | |

| No | 5535 (60.7%) | 829 (68.1%) | 545 (59.3%) | 103 (58.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Income (low) | 2718 (31.1%) | 365 (31.2%) | 321 (37.2%) | 72 (41.6%) | |

| Medium | 3071 (35.2%) | 440 (37.6%) | 316 (36.7%) | 59 (34.1%) | |

| High | 2945 (33.7%) | 366 (31.3%) | 225 (26.1%) | 42 (24.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Education (basic) | 2226 (21.0%) | 291 (20.6%) | 332 (28.9%) | 93 (35.8%) | |

| Intermediate | 4360 (41.0%) | 564 (40.0%) | 480 (41.8%) | 101 (38.9%) | |

| Advanced | 4038 (38.0%) | 556 (39.4%) | 336 (29.3%) | 66 (25.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol use (yes) | 4404 (48.4%) | 657 (53.9%) | 463 (51.1%) | 78 (44.3%) | |

| No | 4695 (51.6%) | 561 (46.1%) | 444 (49.0%) | 98 (55.7%) | 0.001 |

| Smoke (current, heavy) | 748 (8.6%) | 191 (16.4%) | 256 (29.8%) | 33 (20.6%) | |

| Current, light | 245 (2.8%) | 34 (2.9%) | 15 (1.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Former, heavy | 1304 (14.9%) | 309 (26.5%) | 339 (39.4%) | 76 (47.5%) | |

| Former, light | 1981 (22.7%) | 228 (19.6%) | 100 (11.6%) | 17 (10.6%) | |

| Never | 4448 (51.0%) | 403 (34.6%) | 150 (17.4%) | 33 (20.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Smokeless tobacco (yes) | 699 (7.7%) | 131 (10.8%) | 138 (15.2%) | 34 (19.3%) | |

| No | 8401 (92.3%) | 1088 (89.3%) | 769 (84.8%) | 142 (80.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary heart disease (yes) | 718 (6.9%) | 106 (7.6%) | 159 (14.2%) | 31 (13.0%) | |

| No | 9727 (93.1%) | 1281 (92.4%) | 963 (85.8%) | 208 (87.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure (yes) | 191 (2.1%) | 25 (2.1%) | 41 (4.6%) | 9 (5.1%) | |

| No | 8878 (97.9%) | 1194 (98.0%) | 861 (95.5%) | 166 (94.9%) | <0.0001 |

*GOLD reference: no chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality+GOLD zero (chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality)+restrictive (FEV1/FVC >= 0.70 and FVC<80% predicted).

†χ2 or t test.

BMI, body mass index; FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Table 3.

Generalised logistic models: association between edentulism and GOLD stages as compared to dentate subjects

| GOLD reference* | GOLD I | GOLD II | GOLD III/IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 crude | ||||

| Edentulous | Reference | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.24) | 2.06 (1.79 to 2.38) | 3.38 (2.61 to 4.39) |

| Model 2 minimally adjusted† | ||||

| Edentulous | Reference | 1.12 (0.93 to 1.34) | 1.92 (1.61 to 2.28) | 3.17 (2.28 to 4.41) |

| Model 3 fully adjusted‡ | ||||

| Edentulous | Reference | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.28) | 1.32 (1.08 to 1.62) | 2.47 (1.68 to 3.63) |

*GOLD reference: no chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality+GOLD zero (chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality)+restrictive (FEV1/FVC >= 0.70 and FVC<80% predicted).

†Model 2 is minimally adjusted for race/centre (5-level), male and age (years).

‡Model 3 is fully adjusted for race/centre (5-level), male, age (years), diabetes, hypertension, smoking (5-levels), smokeless tobacco, alcohol, income (3-level), education (3-level), congestive heart failure and congestive heart disease.

FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Table 4.

Periodontal measures among the 5155 dentate subjects by GOLD stages

| GOLD reference* | GOLD I | GOLD II/III/IV | Overall p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC/AAP definition | ||||

| Healthy N (SD) | 2378 (43.0%) | 281 (38.1%) | 151 (28.5%) | |

| Entry N (SD) | 2271 (41.1%) | 295 (40.0%) | 233 (44.1%) | |

| Severe N (SD) | 878 (15.9%) | 161 (21.9%) | 145 (27.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Extent PD >= 4 mm | 7.05 (11.3) | 8.12 (12.3)* | 9.66 (14.8)**** | <0.0001 |

| Mean PD | 1.89 (0.56) | 1.94 (0.61) | 2.03 (0.74)**** | <0.0001 |

| Extent AL >= 3 mm | 21.7 (21.8) | 27.6 (26.0)**** | 34.3 (28.7)**** | <0.0001 |

| Mean AL | 1.72 (0.96) | 1.94 (1.15)**** | 2.29 (1.43)**** | <0.0001 |

| Extent BOP | 25.2 (23.4) | 25.1 (24.3) | 27.7 (26.4)** | 0.07 |

| Extent PQ >= 1 | 42.5 (38.3) | 39.3 (37.7)* | 49.9 (39.3)**** | <0.0001 |

| Number of teeth | 22.0 (6.99) | 21.5 (7.26) | 18.8 (8.09)**** | <0.0001 |

*= p<0.05.

**=p<0.01.

***=p<0.001.

****=p<0.0001.

All p values are compared to reference group by χ2 or generalised logistic model.

AAP, American Association of Periodontology; AL, attachment loss relative to cemento-enamel junction; BOP, bleeding upon probing in % of sites; CDC, Center for Disease Control; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; PD, probing depth in mm; PQ, plaque index.

Table 5.

Generalised logistic models: periodontal status (CDC/AAP definition) by GOLD stages

| GOLD I | GOLD II/III/IV | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 crude | ||

| Healthy | Reference | Reference |

| Entry | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.31) | 1.62 (1.31 to 2.00) |

| Severe | 1.55 (1.26 to 1.91) | 2.60 (2.05 to 3.31) |

| Model 2 minimally adjusted* | ||

| Healthy | Reference | Reference |

| Entry | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.19) | 1.42 (1.14 to 1.77) |

| Severe | 1.46 (1.17 to 1.82) | 2.17 (1.67 to 2.80) |

| Model 3 fully adjusted† | ||

| Healthy | Reference | Reference |

| Entry | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.14) | 1.10 (0.87 to 1.39) |

| Severe | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.55) | 1.41 (1.07 to 1.87) |

*Model 2 is minimally adjusted for race/centre (5-level), male and age (years).

†Model 3 is fully adjusted for race/centre (5-level), male, age (years), diabetes, hypertension, smoking (5-levels), smokeless tobacco, alcohol, income (3-level) and education (3-level).

AAP, American Association of Periodontology, CDC, Center for Disease Control; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Table 6.

Self-reported physician diagnosis of bronchitis or emphysema according to GOLD stages

| No chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality | GOLD zero (chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality) | Restrictive disease (FEV1/FVC≥0.7 and FVC<80% predicted) | GOLD I | GOLD II | GOLD III/IV | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self Report (Yes) | 633 (6.5%) | 65 (20.9%) | 64 (10.4%) | 143 (10.1%) | 201 (17.5%) | 89 (34.1%) | |

| No | 9083 (93.5%) | 246 (79.1%) | 551 (89.6%) | 1269 (89.7%) | 949 (82.5%) | 172 (65.9%) | <0.0001 |

*χ2 test.

FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

The distribution of study subjects according to dentate status and GOLD stage is shown in table 1. Among the edentulous subjects (2087), there were 591 or 28.3% with COPD (GOLD stages I–IV). With the exception of GOLD I where the prevalence of edentulism was 14.7%, the prevalence of edentulous individuals increased from 16.4% for GOLD 0 to 35.6% for GOLD III/IV. The crude OR (not shown in table 1) for edentulism being associated with prior COPD versus no COPD was 1.62 (95% CI 1.46 to 1.80). Approximately 13% of individuals with no chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality (ie, no lung disease) were edentulous. There were 2232 subjects with prior COPD (19.6%) among 11 378 dentate subjects.

Table 2 presents the prevalence of various subject characteristics according to GOLD classification. In this table, the GOLD reference group for statistical testing combines the following three categories of subjects: no lung disease, GOLD 0 and subjects with chronic respiratory symptoms but no lung function abnormality. The general patterns reflected in table 2 show that compared with the reference group those subjects in the GOLD III and IV category were much more likely to be edentulous, to smoke, to use smokeless tobacco, to be African American or North Carolina Caucasians, men and somewhat more likely to have lower levels of income and education, and to be older and more likely to have chronic heart failure and heart disease.

Table 3 presents multivariable logistic models for the relationship between edentulous/dentate status and GOLD stages using the GOLD reference group described above. In an unadjusted model individuals with GOLD II and III/IV scores were at significantly higher odds for edentulism that increased with increasing GOLD stage severity (OR=2.06; 95% CI 1.79 to 2.38 and OR=3.38; 95% CI 2.61 to 4.39, respectively). Minimally adjusted models (race/centre, sex and age) showed similar significant effects for GOLD II and III/IV with little attenuation. The increased risks of being edentulous for GOLD II and III/IV categories remain significant, but have slightly lower ORs. However, the fully adjusted model showed more attenuation with the odds for being edentulous being 1.3 (1.08 to 1.62) and 2.5 (1.68 to 3.63) times greater for GOLD II disease and the most severe category GOLD III/IV, respectively.

Table 4 shows the association between periodontal status and GOLD classifications for the dentate subjects. Because of small cell sizes in the GOLD III and IV groups, we combined them with GOLD II. Using the CDC/AAP classification of periodontal disease, which is based upon clusters of clinical signs, there is a significant positive association between higher GOLD stage and severe periodontal disease (p<0.0001). Subjects with GOLD I or GOLD II–IV were more likely to have severe periodontitis than the reference group. With respect to the individual periodontal variables measured as means or extent scores, individuals with a GOLD stage I were more likely to have a greater extent of periodontal pocket depths of 4 mm or more, greater extent of attachment loss of 3 mm or more, a higher mean attachment loss and a greater extent of plaque in their mouths than the reference group. Those with GOLD scores of II–IV were significantly higher on all periodontal measures and had fewer teeth compared with the reference group.

Logistic models for the association between GOLD stage and periodontal status using the AAP/CDC definitions appear in table 5. As in table 4, small cell size resulted in grouping the more severe GOLD stages together as GOLD II/III/IV. In general, the ORs for severe periodontal disease increased with more severe GOLD stage in the crude, minimally adjusted and fully adjusted models. There is also an increase in odds as the severity of periodontal disease increases for the two GOLD categories shown using the periodontally healthy group as the reference group within each GOLD category. Although adjusting for relevant confounders generally decreased the odds, there was still a statistically significant association between higher GOLD stage and severe periodontal disease in the fully adjusted model (OR=1.41; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.87).

The relationship between spirometry-based GOLD classification and self-reported physician-based diagnosis of bronchitis or emphysema is shown in table 6. Participants classified as GOLD III/IV were significantly more likely to have self-reported bronchitis or emphysema. There is a trend for a positive association except for the GOLD zero category. Interestingly, 65.9% of subjects with GOLD III/IV report no diagnosis of COPD suggesting that self-report of bronchitis or emphysema is not a strong predictor of GOLD stage. In fact, of all subjects reporting a positive diagnosis of bronchitis or emphysema 53% demonstrated no evidence of chronic respiratory symptoms and no lung function abnormality.

Discussion

We found a statistically significant association between prior COPD and edentulism, with evidence of an increasing prevalence of edentulism with increasing GOLD stage. Although there was some reduction in the magnitude of effect in the adjusted models, the association between dentate status and GOLD stage remained statistically significant even in the fully adjusted model, with a 1.3-fold increased odds of being edentulous in the GOLD II category and a 2.5-fold increased odds of being edentulous in the most severe GOLD III/IV category in the fully adjusted regression model. This represents the first report of an association between edentulism and COPD in a population with spirometry measurements.

In the subgroup of dentate subjects, there was a significant association between the GOLD II–IV group versus the GOLD reference group and prevalent periodontal disease with a statistically significant increase in the odds of entry level and severe periodontal disease in the crude and minimally adjusted models. In the fully adjusted model, only the association between GOLD II/III/IV and severe periodontal disease (OR 1.41 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.87)) remained statistically significant. This is the first population report to include both full-mouth periodontal examination data as well as spirometry assessments, thereby providing direct confirmation of the association between severe periodontal disease and COPD, as well as a dose–response relationship between these conditions.

While there is no previous published information available about the association between edentulism status and COPD, there is evidence in the literature of an association between periodontal disease and COPD, consistent with the findings of the current study.5–7 The results of this investigation were based on standardised pulmonary function tests and suggest that studies that are based upon self-reported diagnoses can potentially result in statistically significant misclassification error. Our data shown in table 6 suggest that of the 12 297 subjects reporting no diagnosis, 2390 subjects or 19.4% were classified as GOLD I–IV. Among those 433 subjects with GOLD I–IV the positive predictive rate was only 15.3%. These findings suggest that an important strength of the current study was the classification of disease based on an objective biological measure (eg, spirometry) rather than a self-reported measure.

Additional strengths of the current study include the large sample size, the inclusion of African Americans providing some racial diversity of the sample, the use of a full-mouth examination protocol and the collection of information about key confounding variables, including but not limited to: tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes and income. Furthermore, the outcomes of interest, edentulism and periodontal disease, were evaluated using a comprehensive oral examination at visit 4.

The current study must also be considered in light of certain limitations. First, the design of the current study does not allow us to determine the directionality or temporality of any association found. It has been reported previously that the dental ARIC subsample is healthier than the greater ARIC sample and that the edentulous subjects within the ARIC dataset have overall poorer health,9 as compared with the ARIC dental sample. Thus, it is possible that the observed relationship between both edentulism and periodontal disease with prior COPD may be due in part to shared risk factors. There is also the potential bias due to differential loss to follow-up prior to visit 4. The current study included only those subjects with dental history information at visit 4. Finally, it is possible that participants with COPD may have been more likely to be lost to follow-up (compared with participants without COPD) or that participants with more severe COPD may have had a lower probability of surviving to visit 4 than participants with mild COPD or normal lung function. There are no data in this report to mechanistically link edentulism with increased risk for COPD. Previous studies of periodontal disease associations with COPD have discussed the potential role of periodontal infection serving as a chronic repository of pathogenic oral organisms that could be aspirated into the airway to challenge the lungs.6 Periodontal infections are also associated with increases in systemic markers of inflammation including biomarkers such as C reactive protein.13 By analogy, edentulism is commonly associated with denture infections (denture mucositis) which induce mucosal inflammation and unclean dentures can also pose as a chronic reservoir of oral pathogens. However, the potential role of denture-based infection as a potential risk factor for COPD remains to be elucidated.

Conclusions

Edentulism was associated with prior COPD, with an incremental effect observed with increasing GOLD stage. Additionally, among dentate individuals, severe periodontal disease was associated with GOLD classification. This is one of the first analyses of COPD and dentate status, and expands upon the available literature regarding periodontal disease and COPD. Further research is warranted to explore the relationship of edentulism and periodontal disease with COPD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors fulfilled all three of the ICMJE guidelines of authorship to include (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published. ZL had the idea for the study and the analysis was designed by SO, JB and RS. All authors contributed to the design of the tables and writing of the manuscript. SB and JB wrote the discussion, ZL wrote the introduction and SO and SB wrote the results. RS wrote the methods. The manuscript was circulated among all authors, edited jointly and revised by teleconference. The final represents the seventh draft of the working group. In addition, the manuscript clearance was provided by the ARIC committee.

Funding: The primary funding for the ARIC study was provided by National Institute Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) DE-11551, and DE-07310; and ARIC contracts supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Additional support for data analyses was provided by UL-1-RR025747. This work was supported in part by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Wouters EFM. Economic analysis of the confronting COPD survey: an overview of results. Respir Med 2003;97:S3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Eeden SF, Sin DD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a chronic systemic inflammatory disease. Respiration 2008;75:224–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scannapieco FA, Ho AW. Potential associations between chronic respiratory disease and periodontal disease: analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Periodontol 2001;72:50–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scannapieco FA, Papandonatos GD, Dunford RG. Associations between oral conditions and respiratory disease in a national sample survey population. Ann Periodontol 1998;3:251–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia RI, Nunn ME, Vokonas PS. Epidemiologic associations between periodontal disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Periodontol 2001;6:71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass RT, Conrad RS, Bullard JW, et al. Evaluation of microbial flora found in previously worn prostheses from the Northeast and Southwest regions of USA. J Prosthet Dent 2010;103:384–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elter JR, Offenbacher S, Toole JF, et al. Relationship of periodontal disease and edentulism to stroke/TIA. J Dent Res 2003;82:998–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol 2007;78(7 Suppl): 1387–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PMA, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obtsructive Lung Disease (GOLD) workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannino DM, Doherty DE, Buist SA. Global Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification of lung disease and mortality: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Respir Med 2006;100:115–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slade GD, Ghezzi EM, Heiss G, et al. Relationship between periodontal disease and C-reactive protein among adults in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1172–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.