Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to analyse the migration of doctors between the UK and France, in an attempt to identify the reasons for these migrations.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted using a self-completed questionnaire.

Setting

The questionnaire was sent to all British doctors practising in France and to all French doctors practising in the UK.

Participants

The doctors were identified, thanks to official data of the National Medical Councils. There were 244 French doctors practising in the UK and 86 British doctors practising in France.

Outcome measures

A questionnaire was specifically developed for the study to determine the reasons why doctors moved to the other country and their level of satisfaction with regard to their expatriation.

Results

A total of 98 French doctors (of 244) and 40 British doctors (of 86) returned the questionnaire. The motivations of the two studied populations were different: French doctors were attracted by the conditions offered by the National Health Service, whereas British doctors were more interested in opportunities for career advancement, moved to join a husband or wife or to benefit from favourable environmental conditions. Overall, the doctors who responded considered the expatriation a satisfactory experience. After expatriation, 84% of French doctors were satisfied with their new professional situation compared with only 58% of British doctors.

Conclusions

This study, which is the first of its kind and based on representative samples, has led to a clearer understanding of the migration of doctors between France and the UK.

Keywords: Medical Education & Training, Public Health, Social Medicine

ARTICLE SUMMARY.

Article focus

The aim of this paper was to analyse the migration of doctors between the United Kingdom and France, in an attempt to identify the reasons for these migrations.

Key messages

This was a cross-sectional study conducted using a self-completed questionnaire

This questionnaire was specifically developed for the study to determine the reasons why doctors moved to the other country and their level of satisfaction with regard to their expatriation. It was sent to all of the British doctors practicing in France and to all of the French doctors practicing in the United Kingdom. The doctors were identified thanks to official data of the National Medical Councils.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study, which is the first of its kind and based on representative samples, has led to a clearer understanding of the migration of doctors between France and the United Kingdom.

Introduction

Medical migration is an important issue that needs to be understood so that it can be regulated collectively, while allowing individuals to benefit from it.

Doctors are highly qualified workers, and their migration follows known migration patterns for qualified people, often referred to as the ‘brain drain’. The principal reasons for emigration are obvious1: improvement in quality of life (higher level of security, increase in revenue …) and their career prospects.

Migrating doctors follow what could be called a hierarchy of wealth: they migrate to a country that is likely to offer them a better situation than that available in their country of residence.2 3 This phenomenon is called the migration merry-go-round or the migration pyramid. For example, Zambian doctors emigrate to South Africa, while South African doctors emigrate to the UK and British doctors emigrate to Canada, which in turn sees some of its doctors head for the USA. The USA seems to be at the summit of this pyramid; it is the only country that has a positive balance4 with regard to the migratory flow of healthcare professionals. However, medical migration is not simply the flow from developing countries to more developed countries; it also involves movement between developed countries.5–7

The UK health system has always been, and continues to be, largely reliant on immigrants. Foreign-trained medical doctors accounted for 36.8% of all registered medical doctors in 2008, around one-quarter of whom came from the European Economic Area and three-quarters from the rest of the world. In France, immigration of medical doctors has only a marginal impact. It does not solve the difficulties of poor geographical distribution, which is a characteristic of the French health system as there are no obligations but only incentives to set up a practice in isolated areas.

Although migration between developing and developed countries is well known, that between developed countries is not. The search for an improvement in lifestyle or career prospects is not the only parameter in the choice of destination. Cultural or historical links between the two countries or geographical proximity can also play a role in the decision. This is why we decided to explore and describe the phenomenon of migration of medical doctors between the UK and France in an attempt to identify the precise reasons for these migrations.

Materials and methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study on the migration of doctors between France and the UK. This study was organised into two parts: we asked doctors trained in France and those trained in the UK about the reasons behind the decision to expatriate. We used official data from the Medical Councils of Britain and France to establish our list of doctors. These councils are required to create and keep an up-to-date record of all the medical doctors authorised to practice medicine. In the first part, doctors who had trained in France before moving to the UK to practice were identified, thanks to the register of the General Medical Council (GMC) in 2005. The results of this first part as well as the methods and the questionnaire used have already been published.8 9 The second part of the study concerned British doctors registered with the French ‘Conseil National de l'Ordre des Médecins’ (CNOM) in 2009. In addition, the CNOM have sociodemographic data for all the doctors registered, which allowed us to conduct a descriptive analysis of all of the doctors concerned and to assess the representativeness of the sample of respondents.

Doctors who qualified before moving to either the UK or France were asked to complete a questionnaire about the reasons for their decision to migrate. The demographic characteristics and the reasons for their expatriation were gathered via a self-completed questionnaire that contained the same items for the two populations; it was based on the study by Ballard et al10 published in 2004.

The questionnaire comprises various parts: a description of the professional situation, an assessment of the level of professional and personal satisfaction before and after the departure (evaluated on a scale of 1 for very dissatisfied to 5 for very satisfied), questions concerning the motivations behind the expatriation (with predefined options), the estimated duration of the expatriation and the likelihood of a change of nationality. The questionnaires were anonymous. They were sent through the post. Data from the questionnaires were entered anonymously into a database.

Results

The questionnaire was sent to the 264 doctors registered as French by the GMC in 2005; we received 98 responses. As 20 questionnaires were returned because the address was incorrect, the overall response rate was roughly 40% (98 of 244). From the 86 British doctors working in France and registered with the CNOM, we received 40 responses, that is to say 46.5%. As in the first study, 14 completed questionnaires were returned by British doctors who had not done all of their medical studies in the UK. These questionnaires were not taken into account for the motivation analysis. We found no significant difference (χ2 comparison test's p value=0.52) in the proportion of British doctors who had not done all of their medical studies in the UK between our sample of respondent (33%) and the CNOM's data (39%); we therefore assume that our sample of respondents is rather representative.

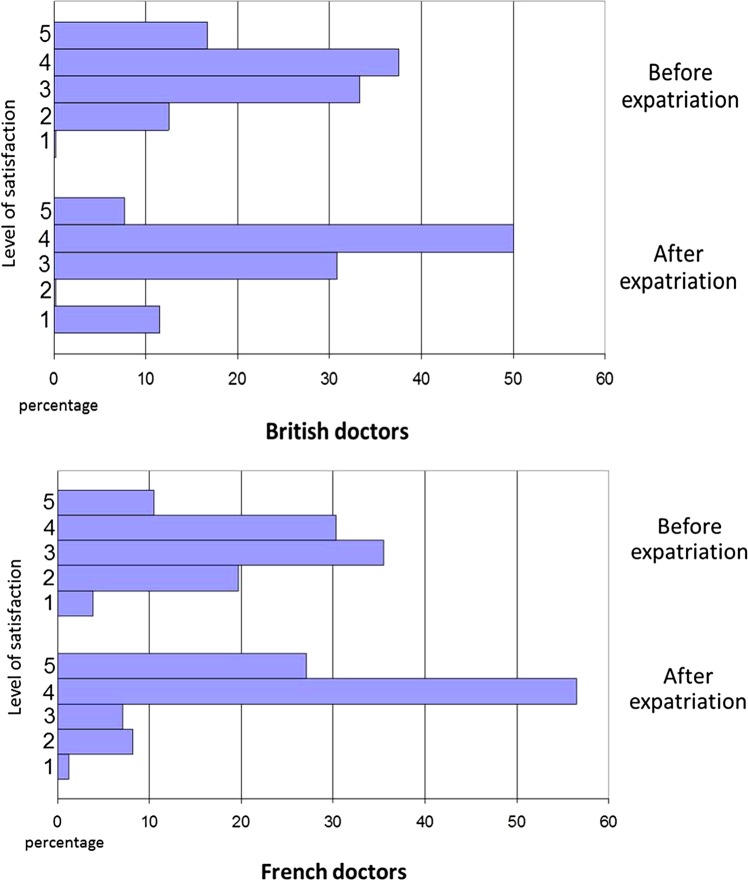

Sex distribution in the two populations was well balanced (figure 1) with a trend towards a greater proportion of women in the British expatriates (sex-ratio 0.95 for French vs 0.85 for British doctors). The mean age was 47 years for British and 44 years for French doctors. In both populations we found a majority of women in younger doctors (less than 50 years) and a majority of men among older doctors.

Figure 1.

Age pyramid.

The doctors who answered the questionnaires believed that they were proficient in the foreign language. Only 19% of French doctors and 11% of British doctors said that they were weak in the foreign language before the expatriation. In addition, language did not seem to be an obstacle to expatriation since even those who had a low level in the foreign language did not wish to have language lessons after the expatriation.

The two populations included a wide range of specialists (table 1). The proportion of general practitioners (GPs) was high in both groups, 48% for the French and 41% for the British expatriate doctors. The majority of GPs were women in the two populations: 58% of French GPs and 57% of British GPs.

Table 1.

Distribution of doctors according to medical specialty

| French expatriate doctors in Great Britain (%) | British expatriate doctors in France (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| GPs | 48 | 60 |

| Medical specialty | 22 | 14 |

| Psychiatrist | 6 | 9 |

| Anaesthesist | 9 | 7 |

| Surgical specialty | 7 | 4 |

| Paediatrician | 3 | 1 |

| OB-GYN | 1 | 1 |

| Others | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

GPs, general practitioners.

In the two populations, the expatriation occurred at roughly the same period in the career. The French doctors had been in practice for an average of 8 years compared with 9 years for the British doctors.

Before expatriation, only 32% of French doctors had worked in the public sector whereas there were 67% of British doctors. After expatriation, the majority of French doctors (68%) opted for the public sector, and the majority of British doctors (67%) remained in the public sector.

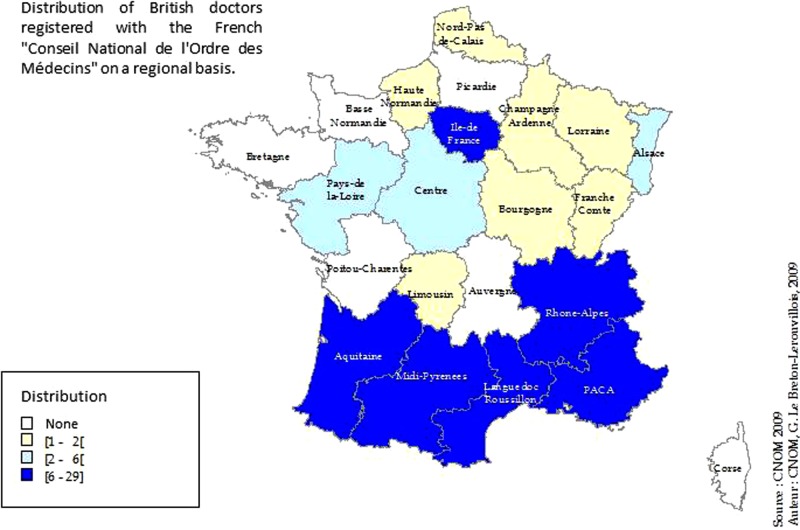

We found three main reasons for expatriation: expatriation for personal reasons, expatriation for professional reasons and expatriation for a combination of professional and personal reasons. In both groups, the reasons were predominantly mixed (figure 2), but were considerably different. The majority of French doctors (59%) and the majority of British doctors (65%) said that they moved for professional and family reasons. For the French doctors, professional reasons were put at the forefront and were principally an increase in revenue11 and an improvement in working conditions and better recognition with regard to both research and training. Also in this group, personal reasons were first the appeal of the British way of life and then family reasons. For the British doctors, the main professional reasons were the interest of a new position with an opportunity for career advancement and dissatisfaction with working conditions in the UK, which prevented them from reconciling their professional and personal lives, notably for those with a spouse in France. In this group the main personal reasons were family reasons followed by the appeal of the French way of life.

Figure 2.

Motivation for expatriation in French and British doctors.

Only 12% of French doctors and 4% of British doctors moved for professional reasons alone. These doctors were mainly men over 40 who were seeking an increase in revenue. Twenty-nine per cent of French doctors and 31% of British doctors moved for family reasons alone. Almost all these moves were made to join a husband or wife.

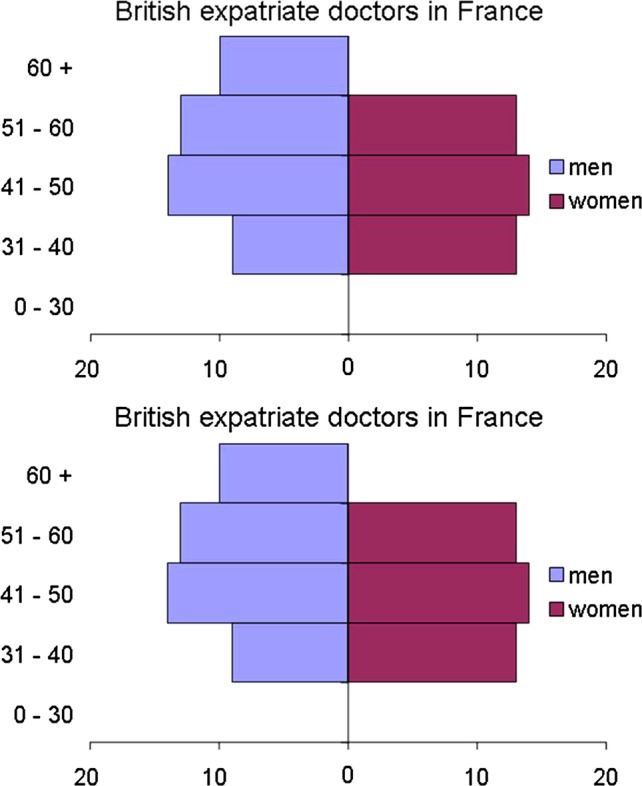

Overall, the doctors who returned the questionnaires were satisfied with the expatriation (mean level of satisfaction 4/5).

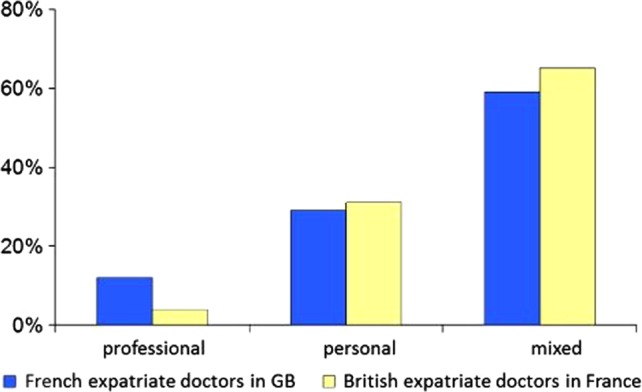

Before the expatriation, the proportion of doctors who were satisfied or very satisfied with their professional situation was greater in the British doctors (54%) than in the French doctors (41%; figure 3). After expatriation, the proportions were inversed: 84% of French doctors were satisfied or very satisfied with their new professional situation compared with 57% of British doctors. The change in the level of satisfaction for each doctor allowed us to assess the gains brought about by the expatriation. From a professional point of view, 54% of French doctors and 50% of British doctors believed that the expatriation allowed them to obtain a more satisfying position. Nonetheless, 12% of French doctors and 19% of British doctors experienced deterioration in satisfaction at work. From a personal point of view, the British doctors were generally satisfied. In fact, most of the British doctors planned to settle in France on a permanent basis (more than 10 years or indefinitely), even though 73% did not wish to apply for French nationality. The majority of British doctors settled in coastal areas of the south of France or in or around Paris (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Level of satisfaction with professional life before and after expatriation.

Figure 4.

Geographical distribution of British doctors with a steady medical practice.

Discussion

This study allowed us to identify the principal features of the migration of doctors between Britain and France. Among these expatriates, there are almost as many men as women, with a slight majority of women in doctors less than 50 years of age and a majority of men in the older doctors. There were doctors specialised in most branches of medicine and GPs accounted for almost half of the total. The motivation for the expatriation was mainly a mixture of professional and personal reasons. For French doctors, the principal professional reasons were an increase in revenue and an improvement in working conditions, while the main personal reason was the appeal of the British way of life. For British doctors, the foremost professional reason was the interest of the new position and an opportunity for career advancement, while the main personal reason was to join another family member.

Overall, the doctors were satisfied with their move (mean level of satisfaction 4/5). However, the reasons for satisfaction for British doctors were not the same as those for French doctors. For British doctors the satisfaction was essentially for personal reasons whereas for French doctors it was essentially for professional reasons. In fact, after expatriation, 84% of French doctors were satisfied with their new professional situation compared with only 58% of British doctors. Almost 20% of British doctors experienced deterioration in their level of satisfaction at work.

Nonetheless, most of the British doctors planned to settle in France for a long time and in some cases definitively. Furthermore, the analysis of the distribution of British doctors around France showed that they were particularly attracted to coastal areas of the south of France and the Paris area. It cannot be inferred from the results that British doctors settle preferably in the Cote d'Azur region because of its climate. The geographic distribution of doctors in France is in towns and cities (including Paris) and the southern regions. It is more plausible that British doctors settle where opportunities are favourable and/or where their partners live—after all the major reason for their expatriation. An interest in the architecture of Paris and/or the south of France may be another reason for migration, as could be the case for any British migrant to France.

In this study, the response rates were 40% and 40.6%, which may seem low. Nonetheless, these rates are relatively good when compared with response rates usually achieved in opinion surveys conducted among doctors which can range from 12.4% for Watson et al12 to 53% for Whalley et al13 In addition, the present study made use of official databases run by the Medical Councils of Britain and France which are required by law to guarantee the accuracy of these registers. Thanks to the official CNOM's registration data, it was possible for us to compare the characteristics of the UK doctors in our study with those on the file provided by the CNOM. This comparison allowed us to show that our sample was representative and that our estimation of the response of British doctors who moved to France was accurate. In addition, as shown by Sax et al,14 the self-questionnaire has several advantages. It reduces the risk of both memory bias and interviewer bias.

Another strength of this study lies in the fact that it allowed us to analyse the migration of doctors between developed countries. Indeed, most of the studies on this subject concern the migration of doctors from developing to developed countries.15 The main reasons as to why doctors migrate from developing to developed countries can be described by the ‘push and pull’ concept.16–19 The term ‘push’ corresponds to factors that are inherent to the country of origin, which push workers to leave (low salaries, political instability and insecurity). In contrast, the term ‘pull’ brings together factors that are inherent to the country of destination, whether intentional or not, that attract foreign workers (better pay, better pension schemes). In this study, no clear-cut ‘push’ factors were found, which shows that the migration of doctors between the UK and France is driven by other factors. As shown by several studies,7 20 21 for European doctors as a whole, both the UK and France are attractive destinations. Moreover, since 2004, EU enlargement has favoured the inflow of medical doctors from new member countries22 23 Unlike the UK,24 France has no active policy and no advertising campaigns to recruit foreign doctors. Consequently, our study shows that UK doctors, who studied in the UK and have moved to France, mainly move to join their partners. In addition, the level of satisfaction after the move, revealed in this study, seems to show that they were well received. It is therefore interesting to note the extent to which our results differ from those reported by Miller et al25 concerning Australian and New Zealand doctors who moved to the USA. The vast majority (more than 82%) of these doctors was men and most were specialists (75%) drawn by university positions. The motivations of these doctors therefore seem to be very different from those of the UK and French doctors. One of the reasons for this difference could be linked to the vigorous recruitment policy in the USA reinforced by very attractive salaries. It therefore seems that for doctors working in developed countries, beyond the classical paradigm of the migration pyramid, the reasons for expatriation are related to quite specific local issues that vary from country to country.

Conclusion

This study, which is the first of its kind and based on representative samples, has led to a clearer understanding of the migration of doctors between France and the UK. It showed that the motivations of the two populations concerned are quite different: French doctors are more interested in the healthcare system, notably the National Health Service (NHS) whereas British doctors are more interested in opportunities for career advancement, or move to join a husband or wife, or to benefit from favourable environmental conditions, notably warmer weather in the south of France. The British healthcare system is very appealing to French doctors, especially GPs, for whom the NHS presents the advantages of easier management of work time, better income and better recognition with regard to both research and training. The NHS is also able to retain British doctors since very few said that they left Britain for professional reasons alone, and once British doctors had settled in France, a large number said they were less satisfied with their professional life. Nonetheless, overall the doctors who returned the questionnaire were globally satisfied with their expatriation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CQ and DC were responsible for the conception and design of this study. GLB and MR provided the data. MH, CQ and RA analysed the data. CQ, RA and DC wrote the manuscript. MH contributed to the initial revision of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the approval of the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CQ is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Martineau T, Decker K, Bundred P. “Brain drain” of health professionals: from rhetoric to responsible action. Health Policy 2004;70:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundred PE, Levitt C. Medical migration: who are the real losers? Lancet 2000;356:245–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchal B, Kegels G. Health workforce imbalances in times of globalization: brain drain or professional mobility? Int J Health Plann Manage 2003;18(Suppl 1):S89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1810–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maier CB. Health professional mobility and health systems - evidence from 17 European countries. Chapter 2: Cross-country analysis of health professional mobility in Europe: the results. UK: World Health Organization - European observatory on health system and policies; 2011

- 6.Ferrera M. The ‘Southern Model’ of Welfare in Social Europe. J Eur Soc Policy 1996;6:17–37 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wismar M, Glinos IA, Maier CB, et al., eds Health professional mobility and health systems: evidence from 17 European countries. UK: World Heatlh Organization, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobson R. Four out of five doctors who emigrate from France to UK satisfied with move. BMJ 2008;337:a2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duverne A, Carnet D, d'Athis P, et al. (French doctors working in Great Britain: a study of their characteristics and motivations for migration). Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2008;56: 360–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard KD, Robinson SI, Laurence PB. Why do general practitioners from France choose to work in London practices? A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2004;54:747–52 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samson AL. Behavior of health care provision and income of GPs: the influence of the regulation of ambulatory medicine. J d'Economie Medicale 2011;29:247–69 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson J, Humphrey A, Peters-Klimm F, et al. Motivation and satisfaction in GP training: a UK cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e645–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whalley D, Bojke C, Gravelle H, et al. GP job satisfaction in view of contract reform: a national survey. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56: 87–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sax LJ, Gilmartin SK, Bryant AN. Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Res Higher Educ 2004;4:409–32 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kangasniemi M, Winters LA, Commander S. Is the medical brain drain beneficial? Evidence from overseas doctors in the UK. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:915–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dovlo D. The brain drain and retention of health professionals in Africa. A case study prepared for a Regional Training Conference on: Improving Tertiary Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Things That Work!; Accra: Medact. 23–25 September, 2003

- 17.Eastwood JB, Conroy RE, Naicker S, et al. Loss of health professionals from sub-Saharan Africa: the pivotal role of the UK. Lancet 2005;365:1893–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein D, Hofmeister M, Lockyear J, et al. Push, pull, and plant: the personal side of physician immigration to alberta, Canada. Fam Med 2009;41:197–201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witt J. Addressing the migration of health professionals: the role of working conditions and educational placements. BMC Public Health 2009;9(Suppl 1):S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Perez MA, Amaya C, Otero A. Physicians' migration in Europe: an overview of the current situation. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cnom 2010;43:253–70 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bach S. Staff shortages and immigration in the health sector. A paper prepared for the Migration Advisory Committee. London: Home Office, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borzeda A, et al. European enlargement: do health professionals from candidate countries plan to migrate? The case of Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. Paris: Ministry of Social Affairs, Labour and Solidarity, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchan J, Dovlo D. International recruitment of health workers to the UK: a report for DfID. London: DfID Health Systems Resource Centre, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller EA, Laugesen M, Lee SY, et al. Emigration of New Zealand and Australian physicians to the United States and the international flow of medical personnel. Health Policy 1998;43: 253–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.