Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether life event stress was associated with greater psychological distress and poorer quality of life in older individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), in comparison with their counterparts without COPD.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Participants

A population-based sample (N=497) of individuals aged 65 and above with COPD (postbronchodilatation FEV1/FVC<0.70, N=136) and without COPD (N=277).

Measurements

We measured life event stress, depressive symptoms (GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale), cognitive symptoms and function (CFQ, Cognitive Failures Questionnaire and MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination), and physical and mental health functional status (SF36-PCS, Physical Health Component Summary and SF36-MCS, Mental Health Component Summary) in participants with and without COPD.

Results

In two-way analysis of variance controlling for potential confounders, life event stress was associated with significant main effects of worse GDS (p<0.001), SF36-PCS (p=0.008) and SF36-MCS scores (p<0.001), and with significant interaction effects on GDS score (p<0.001), SF36-PCS (p=0.045) and SF36-MCS (p=0.034) in participants with COPD, more than in non-COPD participants. The main effect of COPD was found for postbronchodilator FEV1 (p<0.001) and cognitive symptoms (p=0.02).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that life event stress was associated with more depressive symptoms and worse quality of life in individuals with COPD, much more than in those without COPD. Further studies should explore the role of cognitive appraisal of stress, coping resources and psycho-social support in this relationship.

Keywords: Mental Health, Psychiatry, Respiratory Medicine (See Thoracic Medicine)

Artical summary.

Article focus

The impact of life event stress on the mental well-being and quality of life of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Key messages

Our findings showed that in individuals with COPD, life event stress had a greater detrimental effect on mental health and quality of life in comparison with non-COPD individuals.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The case definition for COPD in this study was accurately based on symptom and postbronchial dilatation spirometric measures of chronic airflow obstruction that are diagnostic of COPD according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)-recommended criteria.

The results from this general population-based study are largely free of clinical selection bias, and also controlled for important confounding by demographic and psychosocial variables in the analysis.

Definite causal inferences cannot be made from the cross-sectional findings in this study. Further longitudinal studies are required.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) stands out among chronic diseases with its high and rising prevalence and mortality,1 poor quality of life, frequent hospitalisation and huge societal burden of care.2 Because patients with COPD bear a heavy burden of psychological disturbance, psychiatric morbidity and disability in daily living activities,3 4 the mental health of COPD patients has received growing attention in recent years.

Life event stress is increasingly recognised to play important roles in the development and outcomes of chronic illness such as type II diabetes, coronary heart disease, gastroenterological disorders and obstetric outcomes.5 Stress is well known to result in depression, psychological burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in all age groups, as well as cognitive impairment in late life.6 Among COPD patients, an intrinsic source of stress is directly related to their illness, involving the experience of anxiety and distress provoked by breathing difficulties,7 8 including muddled thoughts, heightened emotions, extreme fear and panic and decreased physical energy, and various difficulties in emotional functioning, sleep and rest, physical mobility, social interaction, activities of daily living, recreation, work and finance. However, the impact of life event stress in general, including those extrinsic to illness-related experience on the physical and mental functioning and quality of life of individuals with COPD in comparison with non-COPD individuals, has rarely been investigated.6 9 10 The aim of this study was to investigate whether life event stress was associated with greater psychological distress and poorer quality of life in older individuals with COPD, in comparison with their counterparts without COPD.

The present study analysed data collected on COPD status, life event stress and measures of pulmonary function, cognitive function, depressive symptoms and quality of life in a population-based sample (Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study)11 to investigate the effect of life event stress on psychological functioning and quality of life. We hypothesised that life event stress in the whole sample would be associated with depressive symptoms and poor quality of life (main effect), but would have a stronger association among individuals with COPD than among non-COPD individuals (interaction), suggesting a greater detrimental effect on depressive symptoms and quality of life. A secondary relationship analysed in two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was the main effect of the COPD status (and its interaction with life event stress) on primary outcomes of pulmonary and cognitive function, based on the known effects of impaired pulmonary and cognitive function in COPD.

Methods

Study design and participants

The participants in the study were a subsample recruited from one locality (Bukit Merah) in the South Central region of Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study (SLAS-2), a prospective population-based cohort study of ageing and health of community-dwelling elderly.12 We interviewed one participant from each household who were Singaporean citizens or permanent residents aged 65 or older who were able to give informed consent. Those who were too frail or ill and unable to complete the interview, for reasons such as from poststroke aphasia, cachexia or profound dementia, were excluded. The participants who completed interviews and provided technically acceptable spirometric data (N=497) represented a response rate of 78.5% of the eligible participants. All participants signed written informed consent for the study that was approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

We identified cases of COPD among the participants who had characteristic symptoms of COPD and spirometric evidence of chronic airflow obstruction (postbronchial dilatation FEV1/FVC<0.70), in accordance with the definition recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).13

Questions from the British Medical Research Council Questionnaire on chronic respiratory symptoms were used to elicit symptoms characteristic of COPD: chronic cough and/or sputum lasting at least 3 months in the year and/or breathlessness on exertion.

Ventilatory function testing was performed using a portable, battery-operated, ultrasound transit-time-based spirometer (Easy-One; Model 2001 Diagnostic Spirometer, NDD Medical Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland). Calibration was checked daily with a 3-litre syringe. Forced expiratory manoeuvres were performed with the respondent seated with recommended guidelines and standardisation of procedures: at least three acceptable manoeuvres, with forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) reproducible within 200 ml. Chronic airflow obstruction as defined as postbronchial dilatation FEV1/FVC<0.70.

Life event stress

Life event stress was measured by an 11-item life events inventory 14 15 that excluded personal illness experiences directly related to COPD. The participants were asked to indicate yes or no as to whether any of 11 life events had occurred over the past year (‘spouse or partner die, a close friend or family member die or have a serious illness (other than your spouse or partner), major problems with money, a divorce or break up, family member or close friend have a divorce or break up, major conflict with children or grandchildren, major accidents, disasters, muggings, unwanted sexual experiences, robberies, or similar events, a family member or close friend lose their job or retire, physically abused, verbally abused, or pet die’). If the participant indicated (a) life event(s) had occurred, he/she was asked to appraise the event and indicate on a scale of 1 (did not upset me) to 3 (upset me greatly) the extent it upset them. Frequency of life event stress was calculated. The scale also provides a life event stress score appraised by the participant that ranged from 0 to 33 with a higher score indicating a participant experienced a greater number of more stressful events.

Depressive symptoms

The presence of depressive symptoms was determined by a depression screening scale for elderly populations, the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) with scores ranging from 0 to 15.16 The GDS was well suited for the study because it is largely free of the measurement artefact due to overlapping somatic symptoms of physical illness(es) and depression. In validation studies in the local older population,17 translated versions of the GDS-15 have been found to be a valid and reliable screening tool for depression: Cronbach's α of 0.80, and intraclass coefficients of test−retest reliability of 0.83 and inter-rater reliability of 0.94. Using a GDS cut-off of ≥5, the GDS-15 has a sensitivity of 0.97 and specificity of 0.95 (area under curve of 0.98) for determining major depressive disorder according to DSM-IV criteria. Depressive symptoms defined as such by GDS≥5 is clinically significant, and such cases including ‘subthreshold’ depression, had been shown in the same population to be associated with significantly poorer mental and physical health and functional status, and more healthcare resource utilisation compared to non-cases and were similar to or worse than syndrome threshold cases of depression.18

Cognitive function

Cognitive function was measured using the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ)19 and the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) which were validated and widely used instruments to assess global cognitive functioning.20 The CFQ uses a five-point Likert-type scale (1=Never, 5=Very often) to evaluate self-reported cognitive problems (eg,‘Do you need to re-read instructions several times?’). Higher CFQ scores indicate more frequent cognitive problems and higher MMSE scores (0−30) indicate better global cognitive functioning, and MMSE scores of 23 or less are considered to be cognitively impaired.

Physical and mental functioning

Physical and mental functional well-being was measured by the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form (SF-36)21 which has been previously validated for use in Singaporeans.22 Weighted summary measures of Physical Health Component Summary (PCS) score and Mental Health Component Summary (MCS) score were computed with higher scores indicating better physical and mental health functioning and quality of life.

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using the software package PASW Statistics (SPSS) V.18. In preliminary univariate analysis, participants with and without COPD were compared with respect to differences in number of life events, and perceived stress score, level of FEV1, CFQ, MMSE, GDS depression, SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores, as well as potential confounding variables, sex, age, ethnicity, smoking status, number of chronic diseases, using t tests or χ2 tests of significance. The independent main effects of life event stress and COPD (independent variables) as well as the interaction effects of life event stress and COPD on measures of pulmonary function, depressive symptoms, cognitive function and quality of life (dependent variables) were analysed using two-way ANOVA using a generalised linear model23 which adjusted for sex, age, ethnicity, smoking status and number of chronic illness. The independent variable of primary interest was life event stress, and the primary outcome variables of interest were depressive symptoms and quality of life. A secondary relationship analysed in the two-way ANOVA model was the main effect of COPD status (and its interaction with life event stress) on primary outcomes of pulmonary and cognitive function. For the outcome variables with significant interaction of life event stress and COPD, the simple effects of their relationships with life event stress score were investigated respectively in participants with and without COPD. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

This study consisted of 497 participants with the average age of 72.1. Among the respondents, 32.9% had COPD, and 67.1% had no COPD. The proportion of respondents with stressful life events in the past 1 year was 43.4%. The sociodemographic and psychological characteristics of study participants with and without COPD are shown in table 1. Participants with COPD were found to have higher mean age (t=3.328, p=0.001), higher proportion of smokers (χ2=20.586, df=3, p<0.001) and increased number of diseases (t=7.096, p<0.001). No significant difference in the number of life events or perceived stress was observed between COPD and non-COPD participants (p>0.05).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, pulmonary and psychological variables of study participants aged 65 or above (Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study, SLAS)

| COPD |

Non-COPD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | Significant test | p Value | |

| Total | 136 | 32.9 | 277 | 67.1 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 58 | 42.6 | 112 | 40.7 | χ2=0.138, df=1 | 0.710 |

| Female | 78 | 57.4 | 163 | 59.3 | ||

| Age (years, M±SD) | 73.19 | ±5.87 | 71.23 | ±5.47 | t=3.328 | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | 121 | 89.0 | 241 | 87.6 | χ2=0.154, df=1 | 0.694 |

| Non-Chinese | 15 | 11.0 | 34 | 12.4 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never smoker | 77 | 57.6 | 211 | 77.3 | χ2=20.59, df=3 | <0.001 |

| Past smoker | 29 | 21.6 | 41 | 15.0 | ||

| Current smoker<10 cigarettes daily | 18 | 13.4 | 12 | 4.4 | ||

| Current smoker≥10 cigarettes daily | 10 | 7.5 | 9 | 3.3 | ||

| Number of chronic diseases | 2.60 | ±1.30 | 1.65 | ±1.25 | t=7.096 | <0.001 |

| Number of negative life events | 0.67 | ±0.98 | 0.74 | ±1.11 | t=0.609 | 0.543 |

| Life event stress score | 1.02 | ±1.71 | 1.12 | ±1.78 | t=0.525 | 0.600 |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 | 1.42 | ±0.50 | 1.75 | ±0.52 | t=6.185 | <0.001 |

| CFQ score | 38.0 | ±9.21 | 38.8 | ±9.83 | t=0.733 | 0.464 |

| MMSE score | 26.4 | ±3.26 | 27.4 | ±3.11 | t=3.090 | 0.002 |

| GDS depression score | 1.13 | ±2.04 | 0.84 | ±1.69 | t=1.487 | 0.138 |

| GDS≥5 | 7 | 5.2 | 8 | 2.9 | χ2=1.349, df=1 | 0.245 |

| SF-36 PCS | 44.6 | ±9.04 | 47.1 | ±7.21 | t=2.726 | 0.007 |

| SF-36 MCS | 54.9 | ±7.83 | 55.1 | ±6.68 | t=0.353 | 0.724 |

Figures in table denote mean±SD or number and %.

Smoker is defined as smoking≥10 cigarettes daily.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CFQ, Cognitive Failures Questionnaire; GDS, the Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; SF-36 MCS, 36-Item Short-Form Mental Health Component Summary; SF-36 PCS, 36-Item Short-Form Physical Health Component Summary.

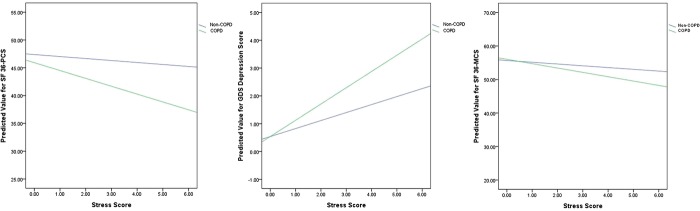

Table 1 shows that compared with those without COPD, participants with COPD had decreased postbronchodilator FEV1 (t=6.185, p<0.001), MMSE score (t=3.090, p=0.002) and SF-36 PCS (t=2.726, p=0.007) score. There were no differences in CFQ and GDS depression scores between participants with and without COPD (p>0.05) in the whole sample. Next, we evaluated the effect of life event stress on GDS, CFQ, MMSE, SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores by subgroups of participants with COPD and without COPD. As shown in table 2, two-way ANOVA in general linear model showed significant main effects of life event stress for GDS (F=64.500, df=1, p<0.001), SF36-PCS (F=7.054, df=1, p=0.008) and SF36-MCS (F=14.710, df=1, p<0.001) scores, and significant interactions of life event stress with COPD were found as well for GDS (F=10.970, df=1, p=0.001), SF36-PCS (F=4.055, df=1, p=0.045) and SF36-MCS (F=4.538, df=1, p=0.034) scores. The simple effects of life event stress on GDS, SF36-PCS and SF36-MCS are shown for participants with and without COPD, respectively, in figure 1. Increasing stress score was associated with higher GDS score, lower SF12-PCS and SF12-MCS scores in participants with COPD, more than in those without COPD after adjusting for potential confounders, indicating the association of life event stress with worse psychological distress and poorer quality of life among individuals with COPD, in comparison with non-COPD individuals. The other significant main effect found in two-way ANOVA was of COPD for decreased postbronchodilator FEV1 (F=17.458, df=1, p<0.001) and higher CFQ scores (F=5.424, df=1, p=0.020) after adjustment of sex, age, ethnicity, smoking status and number of chronic illness, indicating impaired pulmonary and cognitive functions in participants with COPD.

Table 2.

Two-way analysis of variance: Life event stress, COPD and mental and physical variables

| Main effects of COPD (df=1) |

Main effects of stress (df=1) |

Interaction (df=1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p Value | F | p Value | F | p Value | |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 | 17.458 | <0.001 | 0.323 | 0.570 | 2.057 | 0.152 |

| CFQ score | 5.424 | 0.020 | 1.927 | 0.166 | 2.514 | 0.114 |

| MMSE score | 1.799 | 0.181 | 1.159 | 0.282 | 0.380 | 0.538 |

| GDS depression score | 2.353 | 0.126 | 64.500 | <0.001 | 10.970 | 0.001 |

| SF-36 PCS | 0.432 | 0.512 | 7.054 | 0.008 | 4.055 | 0.045 |

| SF-36 MCS | 0.659 | 0.417 | 14.710 | <0.001 | 4.538 | 0.034 |

Adjusted variables: sex, age, ethnicity, smoking status and number of chronic illness.

CFQ, Cognitive Failure Questionnaire; FEV1, Forced Expiratory Volume in the first second; GDS, the Geriatric Depression Scale; MCS, Mental Health Component Summary; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; PCS, Physical Health Component Summary; SF-36, 36-Item Short-Form Healthy Survey.

Figure 1.

Predicted value for SF-36 PCS, GDS depression score and SF 36-MCS in participants with and without COPD SF-36=36-Item short-form Healthy Survey; GDS, the Geriatric Depression Scale; MCS, Mental Health Component Summary; PCS, Physical health Component Summary.

Discussion

The principal finding in this study indicated that life event stress was associated with depressive symptoms and poor quality of life in both COPD and non-COPD participants (main effects), but showed a significantly stronger association among individuals with COPD than among non-COPD individuals (interaction), suggesting a disproportionately greater detrimental effect. To our knowledge, no other studies have reported demonstrating this relationship.

It should be noted that participants with COPD actually did not report greater frequency of occurrence or perceived stress score of non-illness-related life events than non-COPD participants. Instead, individuals with COPD appeared to experience the same number of non-illness-related life events and perceived them to be equally stressful as their non-COPD counterparts, yet showed disproportionately greater psychological distress and poorer quality of life. These results suggest that individuals with COPD may be more vulnerable to the adverse impact of stressful events than non-COPD individuals.

A greater detrimental effect of life event stress on psychological well-being and quality of life in COPD individuals may hypothetically be explained by the possibility that COPD individuals perceive and appraise stressful life events differently to individuals without COPD, or that COPD individuals have poorer coping skills or fewer social and economic resources, or both. We did not have measures of cognitive appraisal, coping resources and social support to explore these hypotheses directly, and this is a limitation of our study.

There are few studies that have investigated the relationship between cognitive appraisal of stressful events, coping strategies and psychological distress in COPD patients. A study by Andrenas and co-investigators24 have assessed how hospitalised patients with acutely exacerbated COPD appraised and coped with a recent stressful event and their level of psychological distress. They reported that half of the respondents tended to perceive their stressful event as representing a threat, 26% as harmful, 7.6% as a loss, 4.3% as a challenge and 11% characterised the stressful event in some other ways. However, the authors found that neither types of stressful event, stress intensity, primary or secondary appraisal, or number of coping strategies used were significantly related to psychological distress. Only problem-solving coping strategies were inversely related to psychological distress. This suggests that poor coping skills may be the principal psychological problem among COPD patients that contribute to their psychological distress and poor quality of life. However, further studies should be conducted.

Our secondary finding of the main effects of COPD on FEV1 was expected and thus not surprising. However, the association of COPD with more frequent cognitive problems was interesting, although the results for MMSE score were not significant after adjustment in two-way ANOVA, possibly due to sample size limitation. These results are consistent with clinical and population studies that indicate significant cognitive effects of COPD on deficits in abstract reasoning,25 complex visual motor process,26 and verbal learning,27 language,28 attention,29 information processing speed29–31 and verbal learning and memory.30 31

The present study has strengths and limitations. The case definition for COPD is accurately based on symptom and postbronchial dilatation spirometric measures of chronic airflow obstruction that are diagnostic of COPD according to GOLD-recommended criteria. Results from this general population-based study are largely free of clinical selection bias, and also controlled for important confounding by demographic and psychosocial variables in the analysis. The measure of life event stress is modified to exclude illness-related stress from chronic diseases in this older population. However, a limitation of the life event inventory is inter-categorical variability and recall bias in the appraisal of the stressful life event.32 In a cross-sectional study, interpreting the causal relationship between stress- and the health-related functional outcomes can be uncertain. Further longitudinal studies are required.

Studies33–35 have reported that mental health status, including anxiety and depressive symptoms, are better predictors of COPD-related quality of life than pulmonary function. The present study supports this observation and further indicates that life event stress has a starkly detrimental effect on mental health and quality of life in patients with COPD. More studies of the effects of stress management and coping strategy in psychological interventions in COPD should be investigated in randomised controlled clinical trials.

It is increasingly being recognised that the identification of mood and anxiety disorders, and psychological and psychosocial interventions to improve mood and reduce anxiety are important for improving patient-centred outcomes in COPD patients. However, in published clinical guidelines such as NICE, where the initial step care management by practitioners in primary care and general hospital settings includes low-intensity psychosocial interventions for patients with persistent subthreshold depressive symptoms or mild-to-moderate depression, there appears to be little attention given to identifying stressful life event(s) and supporting COPD patients experiencing stressful life events to prevent the onset of mood and anxiety disorders. In particular, group-based peer support, individual-guided self-help based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles or computerised CBT to reduce patients’ vulnerability to stress may usefully include objective cognitive appraisal of stress, problem-solving coping skills and relaxation therapy to help support COPD patients experiencing stressful life events.

In conclusion, the present study found that life event stress was associated with more depressive symptoms and worse quality of life in individuals with COPD, much more than in those without COPD. Further studies should explore the role of cognitive appraisal of stress, coping resources and psycho-social support in this relationship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following voluntary welfare organisations for their support of the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies: Geylang East Home for the Aged, Presbyterian Community Services, Thye Hua Kwan Moral Society (Moral Neighbourhood Links), Yuhua Neighbourhood Link, Henderson Senior Citizens’ Home, NTUC Eldercare Co-op Ltd, Thong Kheng Seniors Activity Centre (Queenstown Centre) and Redhill Moral Seniors Activity Centre.

Footnotes

Contributors: TPN was the PI for the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study (SLAS); RK was the PI, and TPN and EHK were co-investigators for the Singapore Successful Ageing Study (SSAS) component of the SLAS; they conceived and designed the study FL(1), FL(2) and MSZN were research fellows and co-ordinators of the SLAS, XYG was the coordinator for the SSAS, and were responsible for the acquisition of the data. YXL and TPN undertook the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. YXL was the lead writer, performed the literature review, and prepared with TPN the initial draught of the manuscript for circulation among all authors for critical interpretation of the results and revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The study is supported by a research grant (No 03/1/21/17/214) from the Biomedical Research Council, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (ASTAR).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Ward E, Hao Y, et al. Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970–2002. JAMA 2005;294:1255–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1436–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang MWB, Ho RCM, Cheung MWL, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:217–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, et al. Influence of anxiety on health outcomes in COPD. Thorax 2010;65:229–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull 2002;128:330–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin MF, Lord C, Andrews J, et al. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2011;96:583–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVito AJ. Dyspnea during hospitalizations for acute phase of illness as recalled by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 1990;19:186–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurney-Smith B, Cooper MJ, Wallace LM. Anxiety and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of catastrophic thoughts. Cogn Ther Res 2002;26:143–55 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gueli N, Verrusio W, Linguanti A, et al. Montelukast therapy and psychological distress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a preliminary report. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;52:e36–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colby JP, Linsky AS, Straus MA. Social stress and state-to-state differences in smoking and smoking related mortality in the United States. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:373–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng TP, Broekman BFP, Niti M, et al. Determinants of successful aging using a multidimensional definition among Chinese elderly in Singapore. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;17:407–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niti M, Ng TP, Kua EH, et al. Depression and chronic medical illnesses in Asian older adults: the role of subjective health and functional status. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:1087–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of Chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease. Executive summary . NHLBI/WHO workshop report 2001

- 14.Andenaes R, Moum T, Kalfoss MH, et al. Changes in health status, psychological distress, and quality of life in COPD patients after hospitalization. Qual Life Res 2006;15:249–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andenaes R. Psychological characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review. J Psychosom Res 2005;59:427–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982;17:37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyunt MSZ, Fones C, Niti M, et al. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging Ment Health 2009;13:376–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soh KC, Kumar R, Niti M, et al. Subsyndromal depression in old age: clinical significance and impact. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:188–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, et al. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br J Clin Psychol 1982;21(Pt 1):1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thumboo J, Fong KY, Machin D, et al. A community-based study of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the English (UK) and Chinese (HK) SF-36 in Singapore. Qual Life Res 2001;10:175–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg SL, Abramowitz SK. Data analysis for the behavioral sciences using SPSS. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002:392.– [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andenaes R, Kalfoss MH, Wahl AK. Coping and psychological distress in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 2006;35:46–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant I, Heaton RK, McSweeny AJ, et al. Neuropsychologic findings in hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 1982;142:1470–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fix AJ, Golden CJ, Daughton D, et al. Neuropsychological deficits among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Neurosci 1982;16:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein M, Gauggel S, Sachs G, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on attention functions. Respir Med 2010;104:52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cerhan JR, Folsom AR, Mortimer JA, et al. Correlates of cognitive function in middle-aged adults. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Gerontology 1998;44:95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anstey KJ, Windsor TD, Jorm AF, et al. Association of pulmonary function with cognitive performance in early, middle and late adulthood. Gerontology 2004;50:230–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sachdev PS, Anstey KJ, Parslow RA, et al. Pulmonary function, cognitive impairment and brain atrophy in a middle-aged community sample. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006;21:300–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min JY, Min KB, Paek D, et al. The association between neurobehavioral performance and lung function. Neurotoxicology 2007;28:441–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychol Bull 2006;132:477–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McSweeny AJ, Grant I, Heaton RK, et al. Life quality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 1982;142:473–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, et al. Functional impairment in COPD patients: the impact of anxiety and depression. Psychosomatics 2000;41:465–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cully JA, Graham DP, Stanley MA, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety or depression. Psychosomatics 2006;47:312–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.