Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to examine longitudinally whether workplace bullying was associated with subsequent psychotropic medication among women and men.

Design

A cohort study.

Setting

Helsinki, Finland.

Participants

Employees of the City of Helsinki, Finland (n=6606, 80% women), 40–60 years at baseline in 2000–2002, and a register-based follow-up on medication.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Workplace bullying comprised questions about current and earlier bullying as well as observing bullying. The Finnish Social Insurance Institution's register data on purchases of prescribed reimbursed psychotropic medication were linked with the survey data. All psychotropic medication 3 years prior to and 5 years after the baseline survey was included. Covariates included age, prior psychotropic medication, childhood bullying, occupational class, and body mass index. Cox proportional hazard models (HR, 95% CI) were fitted and days until the first purchase of prescribed psychotropic medication after baseline were used as the time axis.

Results

Workplace bullying was associated with subsequent psychotropic medication after adjusting for age and prior medication among both women (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.93) and men (HR 2.15, 95% CI 1.36 to 3.41). Also observing bullying was associated with subsequent psychotropic medication among women (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.88) and men (HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.99). The associations only modestly attenuated after full adjustment.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the significance of workplace bullying to subsequent psychotropic medication reflecting medically confirmed mental problems. Tackling workplace bullying likely helps prevent mental problems among employees.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Mental Health, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

Workplace bullying is a prevalent problem, which is associated with poorer mental health based on some previous studies using self-reported measures.

There are no previous studies on workplace bullying and psychotropic medication using longitudinal data and objectively measured, register-based outcome.

We hypothesised that workplace bullying is associated with the risk of psychotropic medication among both women and men, and that these associations are found both for victims of bullying and the observers. Moreover, we hypothesised that the associations remain even after considering key covariates.

Key messages

This study showed that workplace bullying contributes to the risk of subsequent psychotropic medication among women and men who were victims or observers of bullying at their workplace. Also earlier exposures to bullying were associated with psychotropic medication over the 5-year follow-up.

The associations remained after prior psychotropic medication, childhood bullying, occupational class and body mass index, had been taken into account.

These findings further suggest that tackling workplace bullying helps prevent mental health problems among employees.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study was the use of register linkages. Thus, the data on medication were objective and covered all reimbursed psychotropic medication. Furthermore, we were able to consider prior psychotropic medication 3 years before the baseline, as well as had a 5-year follow-up. The data were large and comprised both women and men.

A limitation of this study was that the measures of bullying were based on single items and we were unable to examine the duration and intensity of bullying.

Introduction

Workplace bullying is a prevalent problem in the workforce. In Finland, bullying affects roughly 5–10% of employees.1 2 However, the prevalence of bullying depends on its definition and varies between workplaces and cohorts.3 Albeit there are differences in the definitions and measures of workplace bullying, similar phenomena are likely captured. In general, workplace bullying is about situations at work, where the victims are in an unequal position with respect to their bully and are unable to defend themselves against the negative actions.4 5 Such workplace bullying also is systematic and typically persists over longer periods of time.

Workplace bullying occurs in many different contexts, and its forms can be either mental or even physical towards the victim.4 6 As a consequence, bullying causes psychosocial distress, but the victims of bullying also have a higher risk of both mental and physical health problems.1 2 4 However, few longitudinal studies have been conducted, and both bullying and its health-related consequences have been self-reported. In a previous cross-sectional study in France, associations between workplace bullying and self-reported use of psychotropic medication such as sleep medication, tranquilisers and medication for mental health problems were reported.7 Furthermore, a dose–response was suggested: the longer the exposure to bullying and the higher its frequency, the stronger the associations. Also in some other cross-sectional studies, similar associations between workplace bullying and self-reported psychotropic medication have been reported.1 8–10 Interpersonal conflicts at work have even been associated with higher risk of more severe mental disorders such as long-term psychosis and psychiatric hospital treatment in a prospective Finnish study.11 Our previous prospective studies have shown that workplace bullying at baseline is associated with subsequent self-reported common mental disorders12 and sleep problems13 at follow-up. Earlier prospective findings suggest that victims of bullying also have a higher risk for subsequent depression,2 mental distress14 and sickness absence.15 All these previous studies highlight the adverse consequences of bullying for employee health in general and mental health in particular, as well as productivity at workplaces.16 17

In addition to adverse consequences among the bullied employees, cross-sectional studies have suggested that even observers of bullying may be at risk of health problems.1 7 18 Our previous prospective study included observing bullying at workplace as an indicator of ‘workplace climate’ alongside various psychosocial and other working conditions.19 However, the study did not focus on bullying, and the variable was treated as a dichotomous one. Observing bullying was associated particularly with antidepressant medication among men. Some previous studies also highlight the significance of earlier bullying to subsequent health,20 and even bullying in childhood may contribute to bullying in adulthood.21

Our aim was to examine whether workplace bullying at baseline is associated with subsequent psychotropic medication reflecting medically confirmed mental problems over the follow-up. Covariates, such as prior medication, occupational class, body mass index and childhood bullying, were included for robust evidence about the contribution of workplace bullying to subsequent psychotropic medication.2 7 15 21 Earlier studies have been mainly cross-sectional or based on self-reported mental health. Thus, using more objective register-based psychotropic medication as outcome allows confirming the previous findings relying on self-reports.

Methods

Data

The baseline data were derived from the Helsinki Health Study cohort mail questionnaire surveys among 40- to 60-year-old employees of the City of Helsinki, Finland, in 2000–2002 (n=8960, response rate 67%).22 According to our non-response and attrition analyses, the data are broadly representative of the target population,22–24 except for men, younger participants, manual workers and those with long sickness absence spells are slightly over-represented among the non-respondents. A flow diagram of the study and further details of non-response and attrition are reported elsewhere.22 The City of Helsinki is the largest employer in Finland, and there are around 200 different non-manual and manual occupations.

Psychotropic medication

Psychotropic medication data were derived from the prescription register of the Social Insurance Institution, Finland. These data include all purchases of prescribed reimbursed psychotropic medication, called psychotropic medication for short. The Social Insurance Institution's register data on medication are classified according to the WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification.25 For the present study, all psychotropic medication coded as N05 (psycholeptics) and N06 (psychoanaleptics) was included; medication for dementia (N06D) was excluded. Prior psychotropic medication 3 years before the baseline survey was adjusted for, as a covariate, and the follow-up time after the baseline survey was 5 years or the time until the first purchase of psychotropic medication or death (censored).

The psychotropic medication data were linked with the baseline survey data among those who had given an informed written consent for such linkages (n=6606, 74%). In Finland, each resident has a unique personal identification number that can be used to such register data linkages. After the exclusion of participants with current psychotropic medication at baseline (n=319), the data about eligible participants for this study amounted to 6287. Owing to item non-response to covariates and workplace bullying (approximately 0.5–1.5% per item), the final data used in the analyses comprised 4681 women and 1315 men.

According to our earlier analyses, non-consenters to data linkages were slightly younger, in lower socioeconomic positions and with more medically certified sickness absence spells than consenters.22 23 On the basis of these analyses, the data are representative and consenters and non-consenters to data linkages are broadly similar.

Workplace bullying

We used two questions on workplace bullying in line with previous studies.2 26 The questionnaires included an instruction before the actual questions: “Mental violence or workplace bullying means isolation of a member of the organisation, underestimation of work performance, threatening, talking behind one's back or other pressurizing.”

First, the respondents were asked whether they had been bullied in their current workplace, earlier in the same or in another workplace, never or could not say. Those who reported that they had never been bullied formed a reference category in the analyses to whom the other respondents were compared. A second question asked about observing such behaviour at the respondent's workplace using four response alternatives: not at all, sometimes, frequently or could not say. Those who reported that they did not observe bullying at their workplace were used as a reference category.

Covariates

Age was included as 5-year age groups. Register based previous psychotropic medication 3 years before the baseline survey was included as a covariate. Childhood bullying reported at baseline was asked by a question enquiring whether the participant had been bullied before turning 16 years. Data about occupational classes included manual workers, routine non-manual employees, semiprofessionals professionals and managers. These data were derived from the employers’ personnel registers and completed from the questionnaires for those without consents to link questionnaire data with the registers. Body mass index (BMI) was based on self-reported height and weight at baseline, and was included as a continuous variable.

Ethical approvals

Ethical approvals for the Helsinki Health Study have been obtained from the ethics committees at the Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki and the City of Helsinki Health Authorities.

Statistical analyses

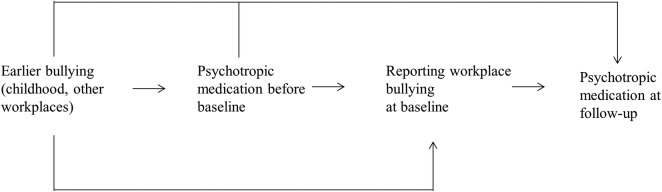

Descriptive statistics on the prevalence of bullying and psychotropic medication among women and men were calculated. A directed acyclic graph shows the assumed causal associations between the key study variables (figure 1). Cox proportional hazard models were fitted to examine the associations between workplace bullying and subsequent psychotropic medication. Days until the first purchase after baseline were used as a time axis. First, age was adjusted for in all the analyses (Model 1). Second, all previous psychotropic medication 3 years prior baseline survey was adjusted for in addition to age (Model 2). All further covariates were added in Model 2. Model 3 was adjusted for childhood bullying. Occupational class was adjusted for in Model 4, and Model 5 was adjusted for BMI. Model 6 was a full model mutually adjusted for all covariates. The results are presented as HR and their 95% CI. The analyses were conducted using SAS statistical programme V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA), and R.27

Figure 1.

A directed acyclic graph (DAG) of the assumed causal associations between the study variables.

Results

Prevalence of workplace bullying and psychotropic medication

Five per cent of women and men reported that they were bullied at baseline (table 1). Additionally, 18% of women and 12% of men reported earlier bullying in the same or another workplace. Around half of women and men had, at least sometimes, observed bullying at their workplace, whereas 8% of women and 7% of men had frequently observed bullying. Many respondents also reported that they did not know if they had been bullied (10% of women and 11% of men) or if they had observed bullying (6% of women and 5% of men) at their workplace.

Table 1.

Distribution (%) of key study variables

| Women (n=4681) (%) | Men (n=1315) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace bullying | ||

| No | 67.3 | 71.8 |

| Yes, currently | 4.7 | 5.3 |

| Earlier, in this or another workplace | 17.8 | 12.2 |

| I do not know | 10.3 | 10.7 |

| Observing bullying at workplace | ||

| No | 36.3 | 42.5 |

| Sometimes | 50.5 | 44.9 |

| Frequently | 7.7 | 7.2 |

| I do not know | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| Any psychotropic medication after baseline | 23.3 | 16.5 |

| Any prior psychotropic medication | 15.7 | 10.4 |

Psychotropic medication was more prevalent among women than among men: 23% of women and 17% of men had at least one purchase of prescribed, reimbursed psychotropic medication over the follow-up, whereas 16% of women and 10% of men had psychotropic medication 3 years prior baseline.

Associations of workplace bullying with psychotropic medication

Workplace bullying was associated with subsequent psychotropic medication (table 2). After adjusting for age, both current (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.19) and earlier bulling (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.35 to 1.80) were associated with psychotropic medication among women (Model 1). Adjustment for previous psychotropic medication (Model 2) somewhat attenuated the associations, whereas the effects of other covariates (Models 3–5) were negligible. Thus, the effect sizes remained similar to Model 2. Current (HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.89) and earlier (HR 1.29, CI 95% 1.11 to 1.50) bullying remained associated with subsequent psychotropic medication even after full adjustment (Model 6).

Table 2.

Workplace bullying at baseline and subsequent psychotropic medication (HR, and their 95% Confidence Intervals, 95% CI from Cox regression models)

| Workplace bullying | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Women (n=4681) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes, currently | 1.72 | (1.34 to 2.19) | 1.51 | (1.18 to 1.93) | 1.49 | (1.16 to 1.90) | 1.50 | (1.17 to 1.92) | 1.51 | (1.18 to 1.93) | 1.48 | (1.16 to 1.89) |

| Earlier, in this or another workplace | 1.56 | (1.35 to 1.80) | 1.31 | (1.13 to 1.51) | 1.29 | (1.11 to 1.49) | 1.31 | (1.13 to 1.52) | 1.30 | (1.13 to 1.51) | 1.29 | (1.11 to 1.50) |

| I do not know | 1.30 | (1.07 to 1.57) | 1.23 | (1.02 to 1.49) | 1.21 | (1.00 to 1.47) | 1.23 | (1.01 to 1.49) | 1.23 | (1.02 to 1.49) | 1.21 | (0.99 to 1.46) |

| Men (n=1315) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes, currently | 2.75 | (1.75 to 4.33) | 2.15 | (1.36 to 3.41) | 1.94 | (1.20 to 3.13) | 2.21 | (1.40 to 3.49) | 2.18 | (1.38 to 3.43) | 1.93 | (1.20 to 3.10) |

| Earlier, in this or another workplace | 2.37 | (1.69 to 3.33) | 1.94 | (1.38 to 2.74) | 1.85 | (1.30 to 2.62) | 1.94 | (1.38 to 2.73) | 1.82 | (1.29 to 2.58) | 1.71 | (1.21 to 2.44) |

| I do not know | 1.52 | (1.00 to 2.30) | 1.26 | (0.83 to 1.92) | 1.25 | (0.82 to 1.91) | 1.29 | (0.85 to 1.97) | 1.23 | (0.81 to 1.86) | 1.23 | (0.81 to 1.87) |

Model 1, age adjusted for; Model 2, age and previous psychotropic medication adjusted for; Model 3, age, previous psychotropic medication and childhood bullying adjusted for; Model 4, age, previous psychotropic medication and occupational class adjusted for; Model 5, age, previous psychotropic medication and body mass index adjusted for; and Model 6, all variables in Models 1–5 adjusted for (full model).

The associations among men were somewhat stronger than among women. After adjusting for age, both current (HR 2.75, 95% CI 1.75 to 4.33) and earlier bullying (HR 2.37, 95% CI 1.69 to 3.33) were associated with psychotropic medication among men (Model 1). As among women, the adjustment for previous psychotropic medication led to the strongest attenuation of the association (Model 2), whereas the effects of other covariates were negligible, and the HRs remained relatively similar to Model 2. Both current (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.20 to 3.10) and earlier bullying (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.44) remained associated with psychotropic medication after full adjustment among men (Model 6).

Also observing bullying at workplace was associated with psychotropic medication among women and men (table 3). After adjusting for age (Model 1), frequently observing bullying was associated with psychotropic medication among women (HR 1.78, 95% CI 1.45 to 2.18). Previous psychotropic medication attenuated this association (Model 2), whereas the effects of other covariates, added in the model including age and previous psychotropic medication, were negligible (Models 3–5). The association remained after full adjustment (Model 6, HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.84).

Table 3.

Observing bullying at workplace at baseline and subsequent psychotropic medication (HR, and their 95% CIs, 95% Confidence Intervals from Cox regression models)

| Observing bullying at workplace | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Women (n=4681) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Sometimes | 1.07 | (0.94 to 1.22) | 1.02 | (0.90 to 1.17) | 1.01 | (0.89 to 1.16) | 1.02 | (0.89 to 1.16) | 1.02 | (0.90 to 1.17) | 1.01 | (0.88 to 1.15) |

| Frequently | 1.78 | (1.45 to 2.18) | 1.53 | (1.25 to 1.88) | 1.51 | (1.23 to 1.85) | 1.52 | (1.24 to 1.86) | 1.53 | (1.24 to 1.87) | 1.50 | (1.22 to 1.84) |

| I do not know | 1.02 | (0.77 to 1.35) | 0.94 | (0.71 to 1.24) | 0.93 | (0.71 to 1.23) | 0.95 | (0.72 to 1.25) | 0.94 | (0.71 to 1.24) | 0.94 | (0.71 to 1.24) |

| Men (n=1315) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Sometimes | 1.38 | (1.02 to 1.86) | 1.27 | (0.94 to 1.71) | 1.25 | (0.92 to 1.69) | 1.25 | (0.92 to 1.69) | 1.22 | (0.90 to 1.65) | 1.18 | (0.87 to 1.59) |

| Frequently | 2.32 | (1.49 to 3.61) | 1.92 | (1.23 to 2.99) | 1.67 | (1.05 to 2.67) | 1.94 | (1.24 to 3.02) | 1.89 | (1.21 to 2.94) | 1.65 | (1.04 to 2.60) |

| I do not know | 1.35 | (0.73 to 2.48) | 1.16 | (0.63 to 2.15) | 1.10 | (0.60 to 2.04) | 1.16 | (0.63 to 2.13) | 1.11 | (0.60 to 2.04) | 1.03 | (0.56 to 1.91) |

Model 1, age adjusted for; Model 2, age and previous psychotropic medication adjusted for; Model 3, age, previous psychotropic medication and childhood bullying adjusted for; Model 4, age, previous psychotropic medication and occupational class adjusted for; Model 5, age, previous psychotropic medication and body mass index adjusted for; and Model 6, all variables in Models 1–5 adjusted for (full model).

Among men, after adjusting for age (Model 1), frequently observing bullying was associated with psychotropic medication (HR 2.32, 95% CI 1.49 to 3.61). The association attenuated but remained after adjustments for covariates (Models 2–5), and after full adjustment (Model 6, HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.60). Also sometimes observing bullying was associated with psychotropic medication among men, but only in the age adjusted Model 1 (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.86).

Further analyses separately examined antidepressant medication, as well as sedatives and anxiolytic medication (data not shown). As the largest part of all psychotropic medication was antidepressant medication, the associations for any psychotropic medication broadly reflected those for antidepressants. However, when only antidepressant medication was examined, the associations were slightly stronger.

Discussion

Principal findings

A particular aim of this study was to examine the associations of workplace bullying with mental health problems using objective register data on psychotropic medication in a longitudinal study design. First, overall, being bullied was associated with psychotropic medication among both women and men. This association remained after considering previous psychotropic medication and several covariates. Second, even earlier bullying was associated with subsequent psychotropic medication among both women and men. Third, also observing bullying at workplace was associated with psychotropic medication, and the association remained after considering the covariates. These findings confirm those from previous cross-sectional studies and, in particular, corroborate associations found between workplace bullying and self-reported mental health.

Previous studies

Comparability to previous studies is limited, as most studies have relied on cross-sectional designs and self-reported medication. However, our results are in accordance with those from an earlier cross-sectional study, which reported an association between workplace bullying and self-reported psychotropic medication among French employees.7 Observing bullying was also associated with psychotropic medication in that earlier study.

Some other, mainly cross-sectional, studies examining the associations between workplace bullying or conflicts at work with self-reported use of sleep-induced drugs, tranquilisers, antidepressants and sedatives have also shown similar associations with ours, suggesting adverse consequences of earlier and current bullying or conflicts at work for psychotropic medication.1 8–10 26 28 29 However, not all these studies have focused explicitly on workplace bullying, and the measurement of psychotropic medication has been limited and mainly based on single self-reported items. Thus, mental health outcomes have been varied and objective measurement such as register-based psychotropic medication has been lacking. The findings of our prospective study using objective data on psychotropic medication avoid reporting bias for medication. Our findings confirm in a longitudinal design the previous cross-sectional and self-reported findings on the significance of workplace bullying to employee mental health problems.

The included covariates had but minor contributions to the examined associations. For example, childhood bullying could have been expected to contribute to the association between current bullying and psychotropic medication, but its contributions were minor. Of those reporting childhood bullying, 11% reported that they were currently bullied as well. It has also been shown earlier that only some of those who have been bullied at school are bullied at workplace as well.21 However, as the validity of retrospective reports on bullying is limited,30 this information does not fully rule out even stronger effects of earlier bullying on the examined associations. To further confirm the possible effects, we excluded those reporting childhood bullying from the analyses (n=459), but the associations remained or were slightly strengthened (data not shown). These sensitivity analyses suggest that the data are not selective to any larger extent and that the results do not reflect sensitivity to the exposure.

Although obesity tends to be stigmatising, bullied employees likely have only slightly higher body mass index.15 Obesity is also connected to mental health problems.31 Nevertheless, body mass index had negligible effects on the examined associations in this study. It is possible that in younger or other type of employee cohorts than our middle-aged public sector cohort, obesity might be a more sensitive issue. Alternatively, the results suggest that workplace bullying and its harmful consequences for mental health are unaccounted by relative weight, and are equally found across bullied employees independent of their body weight. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses adjusting for various other potential confounders related to mental health such as alcohol and smoking, but the results remained unaffected (data not shown). However, it cannot be ruled out that unmeasured covariates affected the findings. For example, negative life events during the follow-up, independent of earlier bullying, might result to anxiety, depression and other mental health problems leading to psychotropic medication.

Psychotropic medication before baseline was adjusted for in our analyses to control for the contribution of workplace bullying to psychotropic medication independent of prior medication, which strongly predicted subsequent medication (data not shown). Sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding all those who had had any psychotropic medication before the baseline but the results were similar to those after adjusting for prior medication. To avoid any selection by covariates and redundant loss of data, we retained the full sample. To further control for potential selection and confounding, and in particular the effects of earlier psychotropic medication on workplace bullying at baseline and psychotropic medication at follow-up, marginal structural equation models were fitted.32 33 The inverse probability weights to fit marginal structural models in a point treatment situation was used for multinomial workplace bullying and observing bullying at workplace.34 Weights were calculated using sex, age, previous psychotropic medication, childhood bullying and BMI as predictors. The results remained unaffected or were even slightly strengthened in these analyses, suggesting that selection and confounding are unlikely to cause major bias to the findings of this study. Nonetheless, previous prospective studies have found bidirectional associations between bullying and mental health suggesting that reverse causation cannot be excluded.2 14 Thus, while bullying might contribute to mental health problems, those suffering from mental problems might be more likely to be bullied or perceive bullying.

Strengths and weaknesses

Some further weaknesses of this study need to be acknowledged. First, our measures for bullying were based on single questions. We lacked information about the specific time frame, duration, intensity and number of episodes of bullying. The associations might be stronger for more persistent, frequent and intense bullying.7 However, in a cross-sectional study, self-reported use of sedatives and hypnotics was not significantly associated with the duration, history or frequency of bullying.1 Bullying is also likely to be remembered and even single episodes could, therefore, have long-lasting effects. Second, negative affectivity has been suggested as a mediator of the association between bullying and mental symptoms.35 We were unable to control for such reporting tendency, but its effects are likely minor in our study where the outcome was derived from objective register data. Third, bullying is a sensitive issue that may be under-reported in surveys. To the extent that this holds for our study, the results are likely conservative. Under-reporting or hiding might also explain why reporting ‘could not say’ to questions on bullying had some associations with psychotropic medication. Fourth, as only the middle-aged employees from the City of Helsinki, Finland, were included, the results may not be directly generalised to other age groups, cohorts or sector of employment. However, there is no particular reason to assume that the associations between workplace bullying and subsequent psychotropic medication would be specific to the current setting. As earlier cross-sectional studies have already shown that workplace bullying is associated with self-reported psychotropic medication,1 8–10 26 28 29 this further suggests that the results probably could apply to other employed groups, too. Finally, a long follow-up period might dilute the findings and changes over the follow-up might affect our findings. However, as we examined the time until the first purchase of psychotropic medication after baseline, and the purchases of medication took place mostly before the end of the 5-year follow-up, the third factors are unlikely to have affected our results to any larger extent.

The strength of this study was large and prospective cohort including register-data linkage on psychotropic medication. While previous studies have mainly been cross-sectional and relied on self-reports of one or few medication groups, our study sheds light on the significance of workplace bullying to objectively measured psychotropic medication and thereby medically confirmed mental health problems more generally. Moreover, we were able to control for various key covariates, and thus our results showed associations of bullying with psychotropic medication independent of age, prior medication, childhood exposures, occupational class and body mass index.

Conclusions

Our study showed that workplace bullying is associated with subsequent psychotropic medication based on objective register data reflecting medically confirmed mental health problems. These associations were found among both women and men. In addition to current workplace bullying, also earlier bullying and observing bullying were associated with psychotropic medication. Workplace bullying needs to be tackled proactively in an effective way to prevent its adverse consequences for mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the City of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Contributors: TL, JH, TP, OR and EL contributed to the planning of the study and analysis, commented on the manuscript text as well as approved submission of the final version. TL conducted the analyses and drafted the first version of the manuscript. JH helped in the analyses.

Funding: This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (grant numbers 1129225, 1121748, 1135630, 1133434).

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare except JH who is currently or recently conducting research sponsored by Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Orion Pharma, Abbott, Novo Nordisk Farma, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Astellas and Takeda.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Vartia MA. Consequences of workplace bullying with respect to the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scand J Work Environ Health 2001;27:63–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, et al. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:779–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agervold M. Bullying at work: a discussion of definitions and prevalence, based on an empirical study. Scand J Psychol 2007;48:161–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einarsen S. The nature and causes of bullying at work. Int J Manpower 1999;20:16–27 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Einarsen S, Raknes BI, Mathiesen SB, et al. Mobbing og harde personkonflikter [Bullying and harsh personalized conflict]. Bergen: Sigma Forlag, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Notelaers G, Einarsen S, de Witte H, et al. Measuring exposure to bullying at work: the validity and advantages of the latent class cluster approach. Work Stress 2006;20:288–301 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niedhammer I, David S, Degioanni S, et al. Workplace bullying and psychotropic drug use: the mediating role of physical and mental health status. Ann Occup Hyg 2011;55:152–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Traweger C, Kinzl JF, Traweger-Ravanelli B, et al. Psychosocial factors at the workplace—do they affect substance use? Evidence from the Tyrolean workplace study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richman JA, Rospenda KM, Nawyn SJ, et al. Sexual harassment and generalized workplace abuse among university employees: prevalence and mental health correlates. Am J Public Health 1999;89:358–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavigne E, Bourbonnais R. Psychosocial work environment, interpersonal violence at work and psychotropic drug use among correctional officers. Int J Law Psychiatry 2010;33:122–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romanov K, Appelberg K, Honkasalo ML, et al. Recent interpersonal conflict at work and psychiatric morbidity: a prospective study of 15,530 employees aged 24–64. J Psychosom Res 1996;40:169–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lahelma E, Lallukka T, Laaksonen M, et al. Workplace bullying and common mental disorders: a follow-up study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lallukka T, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. Workplace bullying and subsequent sleep problems—the Helsinki Health Study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2011;37:204–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finne LB, Knardahl S, Lau B. Workplace bullying and mental distress—a prospective study of Norwegian employees. Scand J Work Environ Health 2011;37:276–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Workplace bullying and sickness absence in hospital staff. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:656–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAvoy BR, Murtagh J. Workplace bullying. The silent epidemic. BMJ 2003;326:776–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Einarsen S, Hoel F, Zapf D, et al. Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice. London & New York: Taylor & Francis, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niedhammer I, David S, Degioanni S, et al. Workplace bullying and sleep disturbances: findings from a large scale cross-sectional survey in the French working population. Sleep 2009;32:1211–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laaksonen M, Lallukka T, Lahelma E, et al. Working conditions and psychotropic medication: a prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47:670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Bully victims: psychological and somatic aftermaths. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008;5:62–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith PK, Singer M, Hoel H, et al. Victimization in the school and the workplace: are there any links?. Br J Psychol 2003;94:175–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahelma E, Aittomäki A, Laaksonen M, et al. Cohort profile: the Helsinki Health Study. Int J Epidemiol Published Online First: 31 March 2012. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laaksonen M, Aittomäki A, Lallukka T, et al. Register-based study among employees showed small nonparticipation bias in health surveys and check-ups. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:900–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martikainen P, Laaksonen M, Piha K, et al. Does survey non-response bias the association between occupational social class and health?. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:212–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment, 2010. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen AM, Hogh A, Persson R, et al. Bullying at work, health outcomes, and physiological stress response. J Psychosom Res 2006;60:63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org/; 2011 (accessed 9 Nov 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appelberg K, Romanov K, Honkasalo ML, et al. The use of tranquilizers, hypnotics and analgesics among 18,592 Finnish adults: associations with recent interpersonal conflicts at work or with a spouse. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1315–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen ÅM, Hogh A, Persson R. Frequency of bullying at work, physiological response, and mental health. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:260–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixon JB. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010;316:104–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 2000;11:550–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robins JM. Association, causation, and marginal structural models. Synthese 1999;121:151–79 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wal WM, Geskus RB. Ipw: an R package for inverse probability weighting. J Stat Softw 2011;43:1–2322003319 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mikkelsen EG, Einarsen S. Relationships between exposure to bullying at work and psychological and psychosomatic health complaints: the role of state negative affectivity and generalized self-efficacy. Scand J Psychol 2002;43:397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.