Abstract

Objective

Prolonged exposure to adults with pulmonary tuberculosis is a risk factor for infecting children. We have studied to what extent a brief exposure may increase the risk of being infected in children.

Design

Observational study of a tuberculosis contact investigation.

Setting

7 day-care centres and 4 after-school-care centres in Norway.

Participants

606 1-year-old to 9-year-old children who were exposed briefly to a male Norwegian with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis.

Main outcome measures

Number of children with latent and active tuberculosis detected by routine clinical examination, chest x-ray and use of a Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST) and an interferon-γ release assay (IGRA).

Results

The children were exposed to a mean of 6.9 h (range 3–18 h). 2–3 months after the exposure, 11 children (1.8%) had a TST ≥6 mm, 6 (1.0%) had TST 4–5 mm, and 587 (97.2%) had a negative TST result. Two children (0.3%) with negative chest x-rays who were exposed 4.75 and 12 h, respectively, had a positive IGRA test result, and were diagnosed with latent tuberculosis. None developed active tuberculosis.

Conclusions

Children from a high-income country attending day-care and after-school-care centres had low risk of being infected after brief exposure less than 18 h to an adult day-care helper with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis.

Article summary.

Article focus

It is well known that prolonged exposure to adults with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis increases the risk of being infected in children.

Limited evidence exists on the risk of brief exposure among children in day-care or after-school-care facilities in high-income countries.

Key messages

Only 2 of 606 (0.3%) children attending several Norwegian day-care and after-school-care centres were diagnosed with latent tuberculosis after being exposed less than 18 h to a highly infectious smear-positive adult helper with pulmonary tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis transmission is complex and may be influenced by other factors than exposure time.

More evidence should be collected before current public health recommendations for the investigation of exposed children in day-care and after-school-care may be changed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This large contact investigation may be the nearest to come to an intervention study.

Reliable information about exposure times was available.

Although it is a strength that latent tuberculosis was diagnosed using a tuberculin skin test in every child and an interferon gamma release assay as a confirmatory test, it is a limitation that the sensitivity of both tests may not be optimal in children.

Introduction

Children are vulnerable and easily develop tuberculosis compared to adults.1 Proximity to contagious individuals and living in small and poorly ventilated rooms increases the risk of being infected.1 Young children and those with impaired resistance may be at an even higher risk.1 Although children may infect each other,2 3 most often adults and in particular adult family members are the source of infection.4 However, children may also be infected outside the family and several outbreaks in schools have documented that weeklong exposure in school classes to an infectious teacher or classmate increases the risk of infection substantially.5 6 An outbreak in a Swedish day-care centre documented that more than half of the attending children were infected after 5 months daily exposure to a preschool teacher with cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis.7 None of 53 children who had visited the centre less than 3 days were infected, suggesting that brief exposure less than 24 h may not be dangerous.7 On the contrary, extensive transmission to both adults and children of particular strains of Mycobacterial tuberculosis has been reported, even after a few hours exposure.8

In February 2010, a 20-year-old native-born Norwegian man was diagnosed with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. During a 3-month long symptomatic period he worked as a helper in seven day-care centres and four after-school-care centres and briefly exposed 606 children, and 136 adult colleagues, family members and friends. Because there was only one likely infectious index case with several hundred contacts, and updated working hour lists at each institution permitted accurate quantification of the maximum exposure times of the children, we have used this event to study to what extent a brief exposure during day-care and after-school-care may increase the risk of being infected with tuberculosis in children.

Methods

Index case

The index case was a 20-year-old native-born Norwegian man who experienced chest pains, chronic cough and night sweating from November 2009 and until he was diagnosed at St. Olavs University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway in February 2010. A chest CT scan revealed numerous infiltrates, bronchiectasis and cavities. Two acid-fast bacilli per visual field were detected by direct microscopy of a spontaneously produced sputum specimen, and acid-fast bacilli were also detected by microscopy in three induced sputum and one bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. Tuberculosis was confirmed by PCR and culture. The M tuberculosis isolate was susceptible to all first-line antituberculous drugs. He recovered after 6 months standard antituberculous treatment.

The contacts

During the 3-month long symptomatic period the index case worked from 1 to 5 days at seven day-care centres and four after-school-care facilities (table 1). In total, he exposed 606 1-year-old to 9-year-old children and 88 adult colleagues (table 1).

Table 1.

Number of children and adults at various day-care and after-school-care centres who were exposed to an adult with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis

| Children | Adults | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Mean age (years) (SD, range) | Number | |

| Day-care centres (total) | 191 | 3.9 (1.0, 1–6) | 44 |

| Centre 1 | 37 | 4.1 (0.7, 3–5) | 7 |

| Centre 2 | 12 | 1.5 (0.5, 1.2) | 4 |

| Centre 3 | 16 | 4.0 (0.7, 3–5) | 3 |

| Centre 4 (3 departments) | 43 | 4.1 (0.8, 3–5) | 17 |

| Centre 5 (2 departments) | 34 | 3.9 (1.0, 3–6) | 7 |

| Centre 6 | 27 | 4.0 (0.8, 3–5) | 3 |

| Centre 7 | 22 | 4.4 (1.1, 3–6) | 3 |

| After-school-care centres (total) | 415 | 7.2 (0.9, 5–9) | 44 |

| Centre 1 (4 classes) | 193 | 7.2 (1.0, 5–9) | 13 |

| Centre 2 (1 class) | 33 | 8.1 (0.2, 8–9) | 8 |

| Centre 3 (4 classes) | 118 | 6.9 (0.8, 6–9) | 10 |

| Centre 4 (3 classes) | 71 | 7.6 (0.7, 7–9) | 13 |

| Colleagues (telemarketing company) | 19 | ||

| Family | 17 | ||

| Friends and girlfriend | 12 | ||

| Total investigated contacts | 606 | 6.1 (1.8, 1–9) | 136 |

The living rooms in all the institutions were approximately 30–40 m2 each, and the ventilation systems were considered to function well. The children spent most time in the living rooms with all doors shut and usually did not go between departments. In the day-care centres, 3–4 h were spent outside in the playground each day. In the schools the index case worked in the after-school programme, usually lasting from 13:00 to 17:00. Less time was spent outside compared to the day-care centres. The index case had never cleaned children or changed diapers, but took part in cooking and helped feeding children. Most of the time he had played with children, but without much physical contact, and he never had children on his lap.

From November 2009 to February 2010 the index case also exposed 19 adult colleagues in a telemarketing office, 17 family members, 11 friends and a girlfriend (table 1).

Contact investigation

All exposed children and colleagues in the day-care and after-school-care centres, and all other adults exposed approximately 8 h or more were investigated. A Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST) was conducted with intradermal injection of two Tuberkulin Units PPD RT 23 SSI (Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark) on the ventral aspect of the left forearm. The transverse diameter of the induration was measured 72 h later. On the basis of specific indications an interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) was performed at St. Olavs University Hospital, using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay (Cellestis, GmbH, Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark), as recommended by the manufacturer. Results were expressed in international units (IU) of the interferon-γ concentration with ≥0.35 IU/ml defined as positive.

BCG vaccination status, nationality and general health status were recorded. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health recommended starting antituberculous medication in all children younger than 2 years as soon as possible after exposure. In the present investigation, all 12 children who were younger than 2 years and many of the older children already had surpassed the ‘window period’ lasting approximately 2 months after the last exposure day during which an immunological response with TST and IGRA may not be expected. Hence, none were started on an early medication, and the majority was examined for the first time approximately 2–3 months after exposure. In the meantime, parents were advised of being alert of arising symptoms. All contacts were initially tested by a Mantoux TST. All children aged less than 2 years and all children older than 2 years with TST ≥6 mm were tested by an IGRA test and chest x-ray. Children with a TST test result of 4–5 mm were tested by an IGRA test, and those with a positive IGRA test result had a chest x-ray. A repeat IGRA test was taken in a few children who had a positive result of the first IGRA test or based on clinical indication.

All children aged less than 2 years and all older than 2 years with symptoms, a positive IGRA result and/or x-ray findings were referred to St. Olavs University Hospital, for further examinations.

Latent tuberculosis was diagnosed in exposed individuals with no clinical and radiological findings who had a positive TST and IGRA test result.

Information regarding the extent of exposure of the children, as evidenced by the number of working hours of the index case at each day-care and after-school-care centre was collected from the stored working hour lists of the index case, and corrected after an interview with the index case.

Statistics

Rates are expressed in per cent and age, and exposure time as mean with SD. A Spearman correlation test is used to evaluate the relation between total exposure time and TST induration.

Results

In all, 572 of 606 (94.4%) exposed children were born as native Norwegian, 2% (12/606) were foreign-born and 3.6% (22/606) were second-generation immigrants (table 2). The mean age of the children was 6.1 years (table 1). Thirty-seven children (37/606, 6.1%) were previously BCG vaccinated (table 2).

Table 2.

BCG status, test results of tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon-γ release assay (IGRA), result of chest x-ray, number of children referred to hospital and number with latent tuberculosis in relation to nationality and specified into age groups less than or more than 5 years for children who were exposed to an adult with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis

| Native Norwegian | Non-native born in Norway | Non-native born abroad | All children | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5 years N=119 |

≥5 years N=453 |

Total N=572 |

<5 years N=10 |

≥5 years N=12 |

Total N=22 |

<5 years N=4 |

≥5 years N=8 |

Total N=12 |

N=606 | |

| BCG vaccinated | 2 (1.7)* | 8 (1.8) | 10 (1.7) | 10 (100) | 9 (75.0) | 19 (86.4) | 1 (25.0) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (66.7) | 37 (6.1) |

| TST 4–5 mm | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) | 6 (1.0) |

| TST ≥6 mm | 2 (1.7) | 5 (1.1) | 7 (1.2) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (13.6) | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (1.8) |

| BCG vaccinated and TST ≥4 mm | 0 (0)† | 3 (37.5) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (100) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (50.0) | 11 (29.7) |

| IGRA positive | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| x-Ray positive | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.3) |

| Referred to hospital | 12 (10.0) | 1 (0.2) | 13 (2.3) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 2 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 16 (2.6) |

| Latent tuberculosis | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (0.3) |

*Number (percentage of children in the column).

†Number (percentage of BCG-vaccinated children).

Test results and diagnoses

Eleven children (11/606, 1.8%) had a positive TST result ≥6 mm, 6 (6/606, 1.0%) had TST results of 4–5 mm, and 587 (587/606, 97.2%) had a negative TST result (table 2). Approximately 30% of the children with a TST ≥4 were previously BCG vaccinated (table 2). In all, 31 IGRA tests were taken in children with positive TST and children younger than 2 years. A second IGRA was taken in six children. Three children had a positive initial IGRA test result, but one of these tested negative when the test was repeated (table 2). One child had perihilar infiltrations on a chest x-ray, which later disappeared spontaneously. Another child had a diffuse infiltrate in the left lung, and was later diagnosed with an atypical mycobacterial infection (table 2). On the basis of the history, clinical findings, results of TST and IGRA tests and chest x-rays, no children were diagnosed with tuberculosis, and only two (2/606, 0.3%) had latent tuberculosis (table 2).

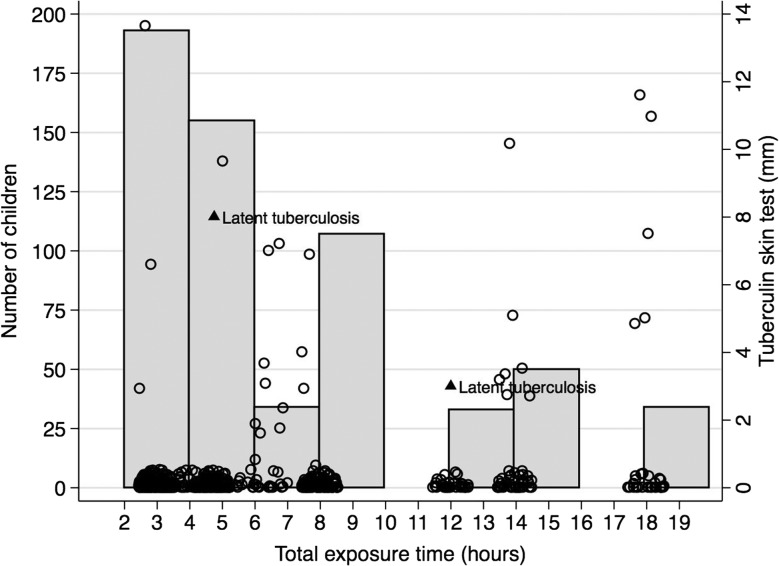

Exposure times

The children had a total exposure time from 3 to 18 h with a mean of 6.9 h (SD 4.7 h, range 3–18 h; figure 1). More than half was exposed between 2 and 6 h (n=360, 59.4%), and about a third (n=223, 36.8%) were exposed more than 8 h. There was a weak correlation between total exposure time and TST test results (r=0.17, p<0.01; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of children who were exposed to an adult helper with smear-positive tuberculosis in relation to tuberculin skin tests induration (mm) and total exposure time (hours).

Description of the individuals with latent tuberculosis

A 9-year-old, healthy non-BCG vaccinated boy was exposed for 4.75 h. He had a positive Mantoux of 8 mm, and negative chest x-ray and IGRA. Three months later, a control IGRA turned out weakly positive (0.49 UI/ml), but the x-ray remained normal. Apart from exposure to the index case, no other risk factors were detected. The boy was diagnosed with latent tuberculosis and completed 3 months preventive treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin. An 8-year-old boy from Nigeria had been BCG vaccinated in his home country, and tested Mantoux negative upon arrival to Norway in 2009. Because he was mentally and physically disabled the index case worked as his personal assistant 4 h everyday for 3 days (in total 12 h). The boy was tested 4 weeks after the exposure and had a Mantoux test result of 3 mm. Eight weeks after the last exposure an IGRA test was weakly positive (0.46 IU/ml). He had no clinical manifestations, and the chest x-ray was normal. He was diagnosed with latent tuberculosis. Recent infection could not be excluded, and he completed 3 months preventive isoniazid and rifampicin treatment.

Eight adults (8/136, 5.9%) were diagnosed with latent tuberculosis, but only two (2/136, 1.5%), a cousin and an uncle who had been in close and longstanding contact with the index case, were considered to have been infected recently (data not shown).

Discussion

We found that only two children in the after-school-care centres developed latent tuberculosis after being exposed less than 18 h to a highly infectious helper with smear-positive lung tuberculosis. No children in the day-care centres were infected. These observations support clinical experience that a brief exposure even to a highly infectious individual may not result in high risk for tuberculosis infection for healthy children. However, other factors than a brief exposure time may have contributed to a low transmission rate in the present context of day-care and after-school-care facilities, such as the fact that the exposure took place in large rooms, that the air quality was good, and in particular that a substantial part of the exposure took place outdoors. A low transmission rate among the non-native children may also be explained by the fact that most were BCG vaccinated. Instead of being the result of environmental factors or patient characteristics, it has been described that particularly efficient human-to-human transmission may be seen with some M tuberculosis strains.8 One healthy 9-year-old boy without risk factors was infected despite a very brief exposure for 4–5 h and it might raise a suspicion that this could be such a highly virulent strain. However, the fact that no more cases evolved during the next 2 years does not support this hypothesis.

Several reports have documented how long-term exposure to adults as well as children with tuberculosis increases the risk of transmission to other children in day-care centres,7 9 in schools6 10 11 and in healthcare institutions in high-income countries.12 Although the evidence of the risk of brief exposure in such institutions is more limited, currently the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and others recommends investigating children who have been exposed to smear-positive individuals more than 8 h.13 14 A Swedish study reported that no tuberculosis transmission took place among 53 visiting children who were exposed to a highly infectious helper less than 3 days in a day-care centre, corresponding to a total exposure time of less than 24 h.7 Thus, our study and the Swedish study quite similarly found that less than 18–24 h exposure may not pose a significant risk for healthy children attending day-care or after-school-care centres in Norway and Sweden. However, tuberculosis transmission is complex and several factors other than exposure time influence the risk of being infected, in particular infectivity of the index case, various characteristics of the exposed children such as low age and vulnerability, and how close the exposure has been in terms of physical contact, room size and air quality.14 Indeed, the fact that both children with latent tuberculosis in the present study had less than 12 h exposure implies that other factors than exposure time might be more important. More evidence on the impact of exposure time therefore should be collected before current guidelines may be changed in line with our observation.

The index case had worked at several different locations during the 3 months he had symptoms. Due to the brief exposure at several places it was difficult to define an inner circle of more heavily exposed children to investigate first, and therefore it was decided to investigate all. We collected information about how long the index case had worked at the various institutions from stored working lists, and adjusted it through an interview with him. Thus, we believe that our estimates of exposure times are reliable. The index case did not work to the same extent with every child, and therefore the exposures of individual children probably have varied. The National Institute of Public Health in Norway at the moment for this contact investigation recommended starting the antituberculous medication in all exposed children less than 2 years as soon as possible.13 However, all 12 children who were younger than 2 years and many of the older children already had surpassed the ‘window period’. Hence no one was started on early medication, and most were examined for the first time approximately 2–3 months after exposure. We used a TST from practical and economic reasons as the primary screening tool, and an IGRA test as a confirmatory test, since the IGRA test may be more specific than TST, even in children less than 5 years old.15 16 We also used IGRA to examine some children with a legible TST result <6 mm in order to increase the chance of detecting infection, but because the diagnostic accuracy of both TST and IGRA tests is not optimal in children less than 5 years of age,15 16 we cannot be sure that all latent cases have been detected. However, one may discuss whether the two children with latent tuberculosis were correctly diagnosed because they only had mildly elevated TST and IGRA test results. However, since latent infection could not be excluded, they were given prophylactic treatment. We found that TST induration correlated weakly with total exposure time. Many of the children with positive TST results were BCG-vaccinated non-native children without any clinical findings, and it may be a strength of the study that they were not classified as infected.

We conclude that Norwegian children attending several day-care and after-school-care centres had a low risk of being infected after brief exposure less than 18 h to a highly infectious adult helper with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. These findings may suggest that contact investigation in day-care and after-school-care centres may be avoided in children who are exposed less than 18 h. However, several factors other than exposure time influence tuberculosis transmission, and more evidence should be collected before current public health guidelines may be changed in line with our observation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Susceptibility testing of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolate was done at the National reference laboratory for mycobacteria at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. We are grateful to Dr Per Eirik Hæreid who participated in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: HD initiated the study and is mainly responsible for the study (guarantor), participated in the analysis of the data and in the writing of the manuscript and revised it critically, and approved the final version; CTR participated in the planning of the study, collected all data, participated in the analysis of the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, revised it critically and approved the final version; IH and JEA participated in the interpretation of the data and in the writing of the manuscript, revised it critically and approved the final version; ES was responsible for the contact investigation, participated in the planning of the study, in the interpretation of the data and in the writing of the manuscript and revised it critically and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None.

Funding: None.

Ethics approval: The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Mid-Norway approved the study, including an exemption to collect informed consents from the participating individuals. The index case accepted to participate in interviews and to publish the information.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Newton SM, Brent AJ, Anderson S, et al. Paediatric tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:498–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paranjothy S, Eisenhut M, Lilley M, et al. Extensive transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from 9 year old child with pulmonary tuberculosis and negative sputum smear. BMJ 2008;337:573–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardona M, Bek MD, Mills K, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis from a 7-year-old child in a Sydney school. J Paediatr Child Health 1999;35:375–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh M, Mynak ML, Kumar L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for transmission of infection among children in household contact with adults having pulmonary tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:624–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewer K, Deeks J, Alvarez L, et al. Comparison of T-cell-based assay with tuberculin skin test for diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a school tuberculosis outbreak. Lancet 2003;361:1168–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caley M, Fowler T, Welch S, et al. Risk of developing tuberculosis from a school contact: retrospective cohort study, United Kingdom, 2009. Euro Surveill 2010;15 www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19510 (accessed 7 Jun 2012) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillman A, Berggren I, Bergstrom SE, et al. Primary tuberculosis infection in 35 children at a Swedish day care center. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:1078–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valway SE, Sanchez MP, Shinnick TF, et al. An outbreak involving extensive transmission of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 1998;338:633–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aivazis V, Pardalos G, Kirkou-Thanou P, et al. Tuberculosis outbreak in a day care centre: always a risk. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higuchi K, Kondo S, Wada M, et al. Contact investigation in a primary school using a whole blood interferon-gamma assay. J Infect 2009;58:352–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts JR, Mason BW, Paranjothy S, et al. The transmission of tuberculosis in schools involving children 3 to 11 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:82–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds DL, Gillis F, Kitai I, et al. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from an infant. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006;10:1051–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuberkuloseveilederen som e-bok. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health. www.fhi.no/eway/default.aspx?pid=233&trg=MainArea_ 5561&MainArea_5661=6034:0:15,5092:1:0:0:::0:0 (accessed 7 Jun 2012)

- 14.Erkens CG, Kamphorst M, Abubakar I, et al. Tuberculosis contact investigation in low prevalence countries: a European consensus. Eur Respir J 2010;36:925–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandalakas AM, Detjen AK, Hesseling AC, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays and childhood tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:1018–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS, Gonzalez-Angulo Y, et al. The utility of an interferon gamma release assay for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection and disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:694–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.