Abstract

Objectives

Traditional microbiology identification takes 48–72 h to complete. This lag forces clinicians to rely on broad-spectrum empiric coverage. To address this gap, manufacturers are developing rapid molecular diagnostics (RMD). We hypothesised that RMD's accuracy is more dependent upon population risk of harbouring the culprit pathogen than to their sensitivity and specificity.

Design

A mathematical model.

Setting and participants

We used the range of risks (5–50%) for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among patients hospitalised with complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI), pneumonia or sepsis.

Main outcome measures

We modelled the impact of changing a test's characteristics on its positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values, and hence the risk of overtreatment or undertreatment, within strata of an organism's population prevalence. MRSA diagnostics provided assumptions for the test sensitivity and specificity (95–99%). Scenarios with low sensitivity and specificity (90%), and best-case and worst-case scenarios normalised to the annual universe of populations of interest, were examined.

Results

With a low prevalence (5%) and high test specificity, the PPV was 84%. Conversely, with 50% prevalence and 95% test specificity the PPV rose to ≥95%. Even when the test's specificity and sensitivity were both 90%, in a high-risk population both PPV and NPV were ∼90%. In the worst-case scenario, 150 000 patients with cSSSI, pneumonia and sepsis annually were at risk for inappropriate treatment, 91% of these at risk for over-treatment. In the best-case scenario, 81% of 18 000 patients at risk for inappropriate coverage were subject to overtreatment.

Conclusions

Although promising for limiting exposure to excessive antimicrobial coverage, RMDs alone will not solve the issue of inappropriate, and particularly overtreatment. Increasing pretest probability as a strategy to minimise antibiotic abuse results in more accurate patient classification than does developing a test with near-perfect characteristics. The healthcare community must build robust evidence and information technology infrastructure to guide appropriate use of such testing.

Keywords: Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

Traditional microbiology identification takes 48–72 h to complete, which forces clinicians to rely on broad-spectrum empiric coverage.

To address this gap, manufacturers are developing rapid molecular diagnostics (RMD).

It is unclear as to what impact RMDs may have in different population on overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Key messages

Although promising for limiting exposure to excessive antimicrobial coverage, RMDs alone will not solve the issue of inappropriate and particularly overtreatment.

Increasing pretest probability as a strategy to minimise antibiotic abuse results in more accurate patient classification than does developing a test with near-perfect sensitivity and specificity.

Strengths and limitations of this study

As a mathematical model, our study relies on the accuracy of estimates in the literature, which predisposes our computations to greater uncertainty.

The model is transparent.

Our findings span a wide range of plausible epidemiology.

The data underscore the need to understand local pathogen patterns, the recognition of which should drive decisions about the utility of these powerful molecular diagnostics.

Introduction

Despite the fact that antibiotics represent a relatively recent advance in medicine, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are now common in both the hospital and the community. Antibiotic misuse and abuse represent a key driver of the increasing prevalence in antibiotic resistance.1 2 The spread of antimicrobial resistance has similarly created a vicious cycle where clinicians repeatedly reach for extended spectrum agents in order to address the current patterns of resistance while potentially worsening them for the future. Underlying this practice approach has been the general unavailability of reliable, rapid diagnostics to help establish the aetiology of an infection. Indeed, traditional phenotypic microbiology methods take 48–72 h to identify an organism when present and to determine the antibiotic susceptibility profile. Without a prompt means for either including or excluding potentially resistant pathogens, clinicians frequently have no alternative but to rely on broad-spectrum options for empiric therapy. Such approach is currently warranted, given the extensive data documenting that delayed and inappropriate antibiotic treatment increases the risk for mortality and prolongs the duration of hospitalisation.3–9 However, rapid and accurate diagnosis should diminish the uncertainty and help target the culprit organisms without straying into the extremes of overly narrow or overly broad coverage.

To fill this diagnostic gap, several manufacturers are engaged in developing rapid diagnostic modalities that incorporate recent advances in molecular techniques relying on genotyping the organisms. Indeed, some of these technologies are able to arrive at the microbiological diagnosis in as little as 2 h, a critical period for tailoring treatment.10 Such improvement in shortening the diagnostic time is invaluable, particularly given these tests’ ostensible accuracy.

At the same time, one must exercise caution because these tests are not 100% accurate. And while manufacturers strive for ever-increasing sensitivity and specificity for their tests, a more fruitful area of investigation may be learning to identify characteristics of specific populations in whom these tests may prove to be most helpful for targeting and tailoring treatment. In other words, the central clinical question may revolve not around issues of sensitivity and specificity intrinsic to the test, but rather around the positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values associated with these newer tools in populations with various levels of risk for the organisms in question. This approach fits in with the Bayesian decision making, whereby the prior probability of an event informs the interpretation of the diagnostic data. Irrespective of the sensitivity and specificity, if the PPV and NPV are not sufficiently high, then these new tests may not help clinicians either to withhold unnecessarily broad coverage or to tailor it shortly after the results return.

We hypothesised that even under conditions where such rapid diagnostic tests had near-perfect sensitivity and specificity, the population-specific risk for having a particular organism would represent a crucial consideration in driving diagnostic accuracy. That is failure to consider the pretest probability of these organisms in the population screened would undermine the potential value of rapid diagnostic tests. To address this question we developed a model simulation evaluating the application of these assays, and relied upon publicly available data to populate our analysis.

Methods

We developed a mathematical model simulating the impact of changing a test's characteristics on its accuracy within several strata of population risk for a particular organism. All the inputs were extracted from publicly available data. The primary outcome of interest was the potential magnitude for overdiagnosis of a particular pathogen, or the proportion of false-positive tests under the varying assumptions. We were specifically interested in the false positive rates, since these cases are the ones most likely to receive overly broad treatment when it is not indicated. Such overly broad treatment represents a key clinical endpoint since it exposes the patient and the healthcare system to adverse consequences individually and as a group. As a secondary endpoint we examined the overall inaccuracy of the test in various scenarios, defined as the sum of the false-positive and false-negative results as a proportion of the total population.

The model was based on the approximate risks of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among three distinct hospitalised populations: (1) complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI)11–13 and (2) pneumonia,11 14 and (3) sepsis.11 We sought the most generalisable estimates for at least two factors of the following three, using the available data to calculate the third when necessary: (1) total volume of hospitalisations for each disease of interest, (2) proportion of the total volume represented by MRSA and (3) total number of MRSA infections in each disease category.11 14–16

For consistency, the assumptions for the corresponding test characteristics mimicked those from MRSA diagnostics.17 To derive estimates for PPV and NPV for a plausible range of test characteristics, we developed four hypothetical testing situations: (1) Test A, with the sensitivity and specificity of 95%, (2) Test B, with the sensitivity 99% and specificity 95%, (3) Test C, with the sensitivity 95% and specificity 99% and (4) Test D, with the sensitivity and specificity 99%. To explore how deviations from the average sensitivity and specificity metrics may impact the accuracy of identification, we conducted sensitivity analyses assuming 90% sensitivity and specificity. Based on the range of MRSA risk estimates in the populations of interest (ie, cSSSI, pneumonia and sepsis), we varied the prevalence estimates from 5% to 50%, and calculated the PPV and NPV for each of the intermediate values.

We additionally performed best-case and worst-case scenario simulations for each population in question. Thus, for the worst-case scenario where all variables were biased against the novel rapid diagnostic assay, we utilised as inputs the highest disease volume and lowest disease prevalence, along with the lowest test sensitivity and specificity values. Skewing the inputs in this fashion provides a potential estimate of the extent and impact of misclassification when all assumptions are shifted so as to constrain the potential value of the rapid diagnostic test in question. Conversely, for the best-case scenario, we input the lowest disease volume and the highest disease prevalence, along with the highest test sensitivity and test specificity. For both of these analyses, the total annual universe of specific disease hospitalisations in the USA was used. We utilised these values to estimate the total numbers of potential cases within each population that would be overtreated (ie, treated for MRSA when no MRSA is present), undertreated (ie, not treated for MRSA when MRSA is present) and treated inappropriately (ie, either overtreated or undertreated).

Both the values for sensitivity and specificity and disease risk were rounded in order to ease computational presentation. Volumes and prevalence of MRSA in the disease states of interest were extracted from several large surveys available in the public domain (table 1). Thus, for the MRSA cSSSI volumes we relied on a study by Klein, which quantified these hospitalisations in 2005.11 The proportions of cSSSI in which MRSA is the offending pathogen derived from two recent epidemiological studies of cSSSI hospitalisations in the USA.12 13 The volume of pneumonia hospitalisations was extracted from the American Lung Association's 2010 data, and the proportion represented by MRSA from a large and representative database analysis by Kollef et al.14 15 Finally, we relied on the Agency's for Healthcare Research and Quality recent statistical brief quantifying the burden of hospitalisations with sepsis, while the Klein study provided the proportion likely caused by MRSA.11 16

Table 1.

Annual hospitalisation volumes

| Infection type | Annual volume | MRSA prevalence (%) | MRSA volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| cSSSI | 434227–1211863 | 15.312–42.713 | 18541511 |

| Pneumonia | 65100015 | 5.6–14.314 | 3654011–9093 |

| Sepsis | 727000–114100016 | 4.9–7.7 | 5624611 |

cSSSI, complicated skin and skin structure infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Results

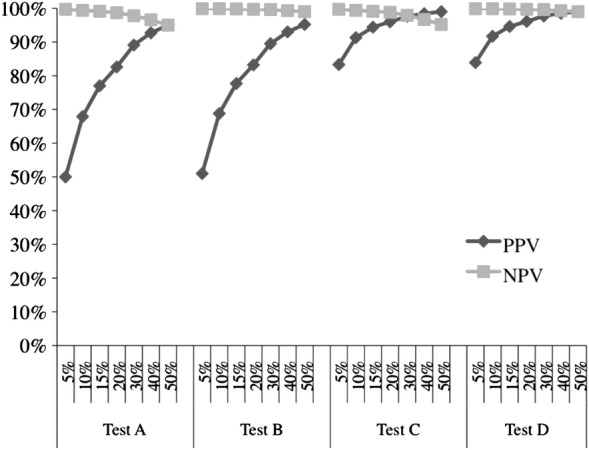

The input assumptions and their sources are presented in table 1. The estimated prevalence of MRSA ranges from approximately 5% in sepsis to nearly 50% in cSSSI, while the prevalence of MRSA in pneumonia falls between those extremes. Under the conditions of lowest prevalence (5%) along with the average test specificity of 95%, the PPV reaches only 50% (figure 1). Improving the specificity by nearly 5–99% without altering the disease prevalence results in a moderate improvement in the PPV to approximately 84%. Alternatively, a change of a similar magnitude in the PPV occurs, when the prevalence of disease increases from 5% to the 10–20% range, even as the specificity remains anchored at 95% (figure 1). The PPV further improves as the prevalence of disease approaches 50%. Notably, at the extremes of disease prevalence and test specificity, the relative improvement in test accuracy is numerically greater when the prevalence is increased while holding the specificity constant (PPV 95% and NPV 95.2% for Tests A and B, prevalence 50%) as compared with a scenario where one modulates the test specificity and maintains the prevalence constant (PPV 83.3% and NPV 83.9% for Tests C and D, prevalence 5%). Put another way, the net change in PPV is maximised based on moderate changes in disease prevalence as opposed to alterations in test sensitivity. As for the NPV, a rise in sensitivity from 95% to 99% does not yield substantial alterations in the value. Essentially, the NPV is already quite high, no matter what the prevalence of resistance in the population. Conversely, the NPV suffers only modestly in the populations where disease prevalence is highest compared with those with the lowest disease prevalence (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positive and negative predictive values of a test with the given sensitivity and specificity, stratified by population disease prevalence.**Percentages along the x-axis represent disease prevalence strata. NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value. Test A: sensitivity=95%, specificity=95%; Test B: sensitivity=99%, specificity=95%; Test C: sensitivity=95%, specificity=99%; Test D: sensitivity=99%, specificity=99%.

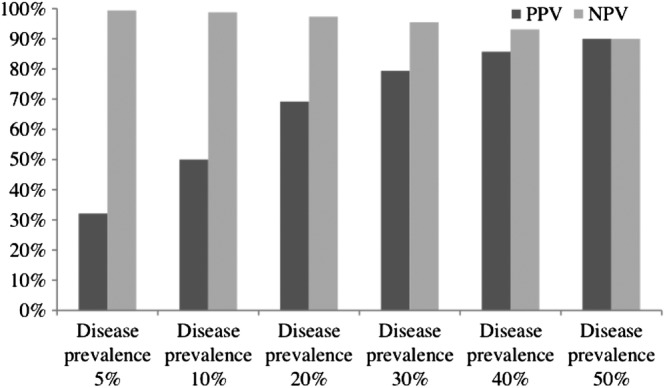

The sensitivity analysis in which we assume that both the sensitivity and specificity of the test equal 90% is illustrated in figure 2. At the lowest prevalence of disease, this specificity affords an unacceptably low PPV (32.1%), while the NPV remains high, exceeding 99%. As the prevalence of the disease rises in the target population, while the test's specificity and sensitivity remain fixed at 90%, the PPV and NPV converge at 90%, indicating a major improvement in the PPV without dramatically compromising the NPV.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis under the conditions of test sensitivity and specificity equalling 90%. NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Best-case and worst-case scenario estimates of the total annual pool of patients at risk for MRSA infection in cSSSI, pneumonia and sepsis demonstrate that the potential for overtreatment far exceeds that for undertreatment (table 2). Focusing on sepsis as an example, for the worst-case calculation we assumed 1 141 000 sepsis hospitalisations annually, a 5% MRSA prevalence, along with test characteristics of 95% sensitivity and 95% specificity. These parameters resulted in 57 050 potential cases of inappropriate treatment reflecting the sum of subjects classified as falsely positive or negative. Of these misclassified subjects, 54 198 (95%) represent those at risk for overtreatment. Conversely, under the best-case assumptions of a high MRSA prevalence (10%) in sepsis (n=727 000), and a test with near-perfect sensitivity and specificity (both 99%), only 7270 individuals are at risk for inappropriate treatment with 6543 (90%) being overtreated (table 2).

Table 2.

Best-case and worst-case scenario simulations for each disease group

| Overtreated | Undertreated | Treated inappropriately | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best-case scenario | |||

| cSSSI | 2600 | 1733 | 4333 |

| Pneumonia | 5534 | 977 | 6510 |

| Sepsis | 6543 | 727 | 7270 |

| Total | 14 676 | 3437 | 18 113 |

| Worst-case scenario | |||

| cSSSI | 51 389 | 9069 | 60 458 |

| Pneumonia | 30 923 | 1628 | 32 550 |

| Sepsis | 54 198 | 2853 | 57 050 |

| Total | 136 509 | 13 549 | 150 058 |

cSSSI, complicated skin and skin structure infection.

Overall, under the worst-case assumptions for all three of the conditions of interest, over 150 000 patients annually with these three conditions may be treated inappropriately, with overtreatment accounting for 136 000 (91%) of this cohort. Under the best circumstances, among the more than 18 000 patients treated potentially inappropriately, nearly 15 000 (81%) may be subjected to overtreatment (table 2).

Discussion

We have demonstrated explicitly that organism prevalence is an important driver of the accuracy of rapid molecular diagnostic tests even when their sensitivity and specificity are near perfect. In addition, we have shown that although improving the theoretical test's specificity results in greater accuracy, one enhances accuracy even more by restricting test utilisation to a population at an increased risk for infection with the pathogen in question. In other words, increasing pretest probability as a strategy to minimise antibiotic abuse results in more accurate patient classification than does developing a marginally superior rapid diagnostic test with near-perfect specificity. In fact, given the already high NPV, the new molecular diagnostics have the potential to limit the use of empiric broad-spectrum coverage substantially. However, although promising for limiting exposure to excessive antimicrobial coverage, molecular diagnostics are still likely to result in a substantial amount of inappropriate treatment. The vast majority (over 90%) of such inappropriate coverage is due to overtreatment in scenarios where the test is applied irrespective of considerations of the prevalence of a resistant pathogen.

Our data have several important implications. First, as manufacturers, regulators and clinicians consider what tests may have superior characteristics, it is important for all stakeholders to engage in defining the appropriate populations for testing with these novel technologies. Our data clearly demonstrate that rather than expending resources for every laboratory to elevate their sensitivity and specificity to close to 100%, the more fruitful effort may be to develop algorithms to identify those patient populations at high risk for the disease being tested. This is particularly true given that marginal enhancements in sensitivity and specificity often come at the cost of substantial financial investments. Second, raising the sensitivity of these technologies even beyond the current levels may be pursuing diminishing returns, given the already high NPV. That is, even when the sensitivity is no higher than 90%, the negative predictive value reaches very high levels (over 95%) in the setting of moderate pretest probability for disease.

Third, and possibly most important, by using genotyping as opposed to phenotyping employed in the traditional microbiology laboratory methods, molecular diagnostics promise to result in sensitivity values that far exceed those of the traditional techniques. The flip side of this optimisation in sensitivity is a blunting in specificity, whereby it may become unclear whether the identified organism is indeed the cause of the clinical condition. Our data indicate that the true need in diagnostic testing lies not in further optimisation of sensitivity, but in improving the specificity of the results.

Because improvements in one by necessity lead to detriments in the other, future directions in molecular diagnostics require thoughtful planning. We have clearly shown that, in order to live up to the promise of improved targeting of antibiotic treatment, such planning must include careful consideration of the populations in whom molecular diagnostic techniques are appropriate. In fact the most important lesson from our simulation is that we need to develop algorithms to help identify patients belonging to populations with a high risk for the particular pathogen. If a predictive algorithm is able to enrich the population to be tested to the disease prevalence between 30% and 40%, both PPV and NPV will be moved into a useful range even when the test's sensitivity and specificity are both well below 100%. With the advent of health informatics and the massive growth in computing ability, turning reams of patient data into predictive equations is a clearly needed functionality. Already several computing systems are addressing this need, and the trend should continue with the input from all stakeholders.18 19

Our study has a number of limitations. The most important limitation is that it is merely a mathematical model, and, as such, by necessity relies on the accuracy of estimates in the literature. The fact that some of the papers we used for deriving our assumptions themselves were modelling exercises,11 predisposes our computations to greater uncertainty. This, however, does not negate our findings that span a wide range of plausible epidemiology. Furthermore, our model underscores the need to understand local pathogen patterns, the recognition of which should drive decisions about the utility of these powerful molecular diagnostics.

In summary, molecular diagnostics promise to streamline identification and treatment of many infectious diseases. While the emergence of these powerful technologies is a positive development, we need to attend to developing algorithms to aid in selecting appropriate patients for their use. Indiscriminate application of molecular diagnostics to all-comers presenting with signs of an infection without consideration for pretest probability of disease is likely to result in a great deal of antimicrobial overtreatment. This will then only accelerate the current trajectory of escalating resistance. In conjunction with developing these important technologies, it is incumbent upon the healthcare community to build robust evidence and information technology infrastructure to guide the appropriate use of such testing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MDZ participated in the conception and design of the study, data analyses and interpretation and drafting and revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AFS refined the study idea, design and interpretation and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:159–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spellberg B, Guidos R, Gilbert D, et al. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: a call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:155–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Micek ST, Kollef KE, Reichley RM, et al. Health care-associated pneumonia and community-acquired pneumonia: a single-center experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:3568–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schramm GE, Johnson JA, Doherty JA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus sterile-site infection: the importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2069–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibrahim EH, Sherman G, Ward S, et al. The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting. Chest 2000;118:146–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez-Lerma F. Modification of empiric antibiotic treatment in patients with pneumonia acquired in the intensive care unit. ICU-Acquired Pneumonia Study Group. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:387–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iregui M, Ward S, Sherman G, et al. Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 2002;122:262–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Antimicrobial therapy escalation and hospital mortality among patients with health-care-associated pneumonia: a single-center experience. Chest 2008;134:963–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Hospitalizations with healthcare-associated complicated skin and skin structure infections: impact of inappropriate empiric therapy on outcomes. J Hosp Med 2010;5:535–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson LR, Liesenfeld O, Woods CW, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the LightCycler methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) advanced test as a rapid method for detection of MRSA in nasal surveillance swabs. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:1661–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Hospitalizations and deaths caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999–2005. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1840–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipsky BA, Weigelt JA, Gupta V, et al. Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007;28:1290–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins TC, Sabel AL, Sarcone EE, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:895–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest 2005;128:3854–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Lung Association Trends in Pneumonia and Influenza Morbidity and Mortality, 2010. http://www.lungusa.org/finding-cures/our-research/trend-reports/pi-trend-report.pdf (accessed 17 Jan 2012)

- 16.Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, et al. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS data brief, no 62 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db62.pdf (accessed 1 Feb 2012) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BD molecular diagnostic solutions BD GeneOhm Staph SR Assay package insert. http://www.bd.com/geneohm/english/products/pdfs/staphsr_pkginsert.pdf (accessed 15 Feb 2012)

- 18.Pepitone J. IBM's ‘Jeopardy’ computer lands health care job. CNNMoney 2011 Sep 12, http://money.cnn.com/2011/09/12/technology/ibm_watson_health_care/index.htm (accessed 15 Feb 2012)

- 19.Terry K. Futuristic Clinical Decision Support Tool Catches On. InformationWeek Healthcare 2012 Jan 27, http://informationweek.com/news/healthcare/clinical-systems/232500603 (accessed 15 Feb 2012)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.