Abstract

Objectives

To conduct a content analysis of pre-Games local media coverage of the potential impact on health and the determinants of health in Newham, the site of the Olympic Park.

Design

Local newspaper content analysis.

Setting

Olympic park host site of the London Borough of Newham.

Outcome measures

Media coverage of employment, physical activity and well-being.

Results

Three hundred and 51 articles meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis. The overwhelming majority of the articles took a positive perspective on the Olympic Games being hosted in Newham with less than 10% (32/351) addressing potential adverse effects. The frequency of articles reporting on both employment and well-being increased significantly over time (p=0.002 and p=0.006, respectively). A non-significant increasing trend was observed for physical activity (p=0.146). New employment opportunities and the promotion of physical activity in young people were the pathways most frequently reported in the local media. However, much less attention is devoted to understanding the uncertainties about how much of these new opportunities will directly improve the determinants of health in the Newham population.

Conclusions

Pre-Games reporting on the impact on health and the determinants of health increased over time in the London Borough of Newham, and is overwhelmingly positive. However, specific uncertainties around the true nature of its impact on local employment and physical activity were articulated. Further evaluation of the tangible impacts on population health, and the determinants of health and health inequalities from the London 2012 Olympics, is required.

Keywords: Public Health, Qualitative Research, Social Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

This article aims to assess pre-Games local media coverage of the potential impact on health and the determinants of health in the London Borough of Newham.

Key messages

Local media coverage of the pre-Games pathways and impacts on health in the host borough of Newham was overwhelmingly positive.

New employment opportunities and the promotion of physical activity in young people are the most frequently covered pathways for improving health.

There are uncertainties around to what extent new jobs will be taken by local people and what meaningful change in exercise behaviour will be realised as a result of the promotion of physical activity.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Newham is one of the most deprived populations in England. This analysis is the first of its kind to assess pre-games pathways and impacts on health and the determinants of health in the local community.

Over 350 individual reports contributed to this manuscript. This media content analysis highlights the lack of attention given to uncertainties and potential adverse effects of the London Games upon Newham.

We did not examine other potentially relevant local sources of information, for example, magazines, websites, regional television news which may have included useful counter-perspectives on hosting the 2012 Games.

Introduction

On the 6 July 2005, the International Olympic Committee awarded the London bid the rights to host the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. As a sporting ‘mega event’ the games have been presented as an opportunity for ‘legacy’, primarily through the development and regeneration of the Olympic Park site in Newham, East London. Newham is seen as a good candidate for regeneration as it is one of the most deprived populations in England with high rates of child poverty and childhood obesity, poor engagement in physical activity, low-employment rates and low-life expectancy.1 Urban regeneration is often framed as a means of addressing inequality and exclusion by improving the built environment and local economy, and thereby providing enhanced employment, social, health, educational and recreational opportunities.2 One of the most consistent findings in public health research is that people living in deprived areas experience poorer health than people living in non-deprived areas.3

Despite arguments that sporting ‘mega events’ are financially rewarding for host cities, questions remain about the potential of such events for facilitating socioeconomic change and providing health benefits.4 Systematic reviews have reported a contrasting picture of improved investment in public services, but delays in health and education provision.5 Assumptions made about intuitive benefits from increased tourism have also failed to materialise in previous Games such as in Sydney or Seoul.6 Satisfaction with the local area after the ‘mega events’ often improves, along with concomitant rises in house prices. In fact, housing costs in the London borough of Hackney may have risen as a result of the anticipated London Games, which is a positive economic outcome but also serves to further fuel local gentrification and a loss of space for disadvantaged groups.7

The final cost of the 2012 games are estimated to be between £9 and £11 billion.8 As such, understanding how pathways of impact are described and understood, with an assessment of which are deemed to be the most important to local media/community, and what if any, translate to impacts on health and health inequalities is crucial.9 Indeed, the media plays a part in setting and linking public and policy agendas.10 It is an important source of knowledge and understanding for the local population11 as well as potentially influencing behaviour change.12 Accordingly, the aim of this study is to conduct a content analysis of pre-Games local media coverage of the potential impact on health and the determinants of health in Newham, the site of the Olympic Park. Local newspapers were chosen for analysis, as opposed to national newspapers, because they cover issues specific to the local community and as such are likely to more informatively describe anticipated pathways to impacting on key determinants of health.

Methods

Data collection

The London Borough of Newham has a population of around 240 000 people. The Borough is ethnically diverse with one of the lowest proportions of White British residents in the country. The two local newspapers circulated in Newham are ‘The Docklands and East London Advertiser’ and ‘The Newham Recorder’. These are two weekly tabloid newspapers with circulations of 20 597 and 16 302, respectively. Both local papers are the only relevant Newham-based media sources on the Nexis UK electronic database. We focused on three legacy outcomes. First, physical activity which, through the motto ‘inspire a generation’, has been proposed as a key legacy of London 2012.13 14 Second, employment has been identified as the main legacy associated with the Olympics by local authority stakeholders. Third, improving well-being is a policy goal of the current government.15 These outcomes are also consistent with the health-related legacy objectives highlighted by the Olympic Park Legacy Company16 and have a well-established evidence base as key social and behavioural determinants of physical and psychological health.2 5 17–20 As such, these outcomes were judged to be the most informative for construction of a conceptual framework for the pathways and mechanisms underlying the relationship between hosting the London 2012 Olympics and health.21 We defined these legacy outcomes as described below. Our interest lay in the extent of coverage and article content relevant to these three areas in local newspapers:

Employment: coverage of how the Games could impact on the generation of new paid employment, assistance to find employment, the provision of work experience opportunities or commercial success that could lead directly to the provision of new employment positions.

Physical activity: stories related to how the Games might impact on sporting or exercise behaviour in members of the local community.

Well-being: coverage of how the Games impacts on members of the community in terms of being healthy, happy or prosperous and not related to physical activity or employment.

The Nexis UK database were searched for electronic articles on the entire available date range at the time of the study (4 November 2010 to the 31 January 2012). The search terms were health* OR well-being, or employ*, or physical OR exercise, or Stratford OR Newham and Olympic OR investment. Table 1 summarises article inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following conventional systematic review methods,22 all articles were screened initially for eligibility by title, then summary and finally full text.

Table 1.

Article inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| ▸ Coverage on issues related to employment, physical activity or well-being of the Newham population as a result of the 2012 Olympics | ▸ Repeated articles ▸ Letters to the editor ▸ Guest appearances of Olympic athletes ▸ Coverage on employment, physical activity or overall well-being not related to the 2012 Olympics |

Data analysis

Outcomes related to employment, physical activity or well-being reported in the included newspaper articles were measured in frequency counts. Frequencies were generated by assessing when an article reported on issues relating to employment, physical activity or well-being and was linked to the 2012 Olympics, for example, investment and new jobs brought to Newham directly as a result of the Games (employment), community sports events directly inspired by the Games (physical activity) or investment in health infrastructure as a result of the Games (well-being). These frequencies were then reported per calendar month. Linear regression analysis was conducted to assess trends over time23 using SPSS V.19 (SPSS inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) with the significance set at p<0.05.

A qualitative framework analysis adapted from the Ritchie and Spencer Thematic Framework Analysis24 25 was used to identify the key themes that suggest potential pathways of impact related to the Olympics. The five steps used were: familiarisation, identifying thematic framework, indexing, charting and mapping. Thirty articles were selected at random and read repeatedly. A preliminary framework was constructed based on the primary outcomes of interest, that is, employment, physical activity and health and well-being. A further 25 articles were selected at random and read with the coding framework being applied. Working independently, a second reviewer (LB) read the same 55 articles to check the validity of the framework. Differences in interpretation were explored, and consensus was reached through discussion.25

A final coding framework with relevant example quotes mapped from the included newspaper articles, divided into the three broad thematic categories (employment, physical activity and well-being) were then divided into a total of 27 subcategories. Newspaper articles were analysed for manifest content,26 that is, what is explicitly stated and draws on the objective and replicable qualities of quantitative methods. All articles were then coded by MS resolving any doubts by discussion with LB. When coding the full data set of articles, any relevant minor alterations to the coding framework were made in parallel, as necessary. Frequency and proportions of articles covering potential determinants of health including employment, physical activity and health and well-being relevant to the 2012 Olympic Games were then calculated.

Results

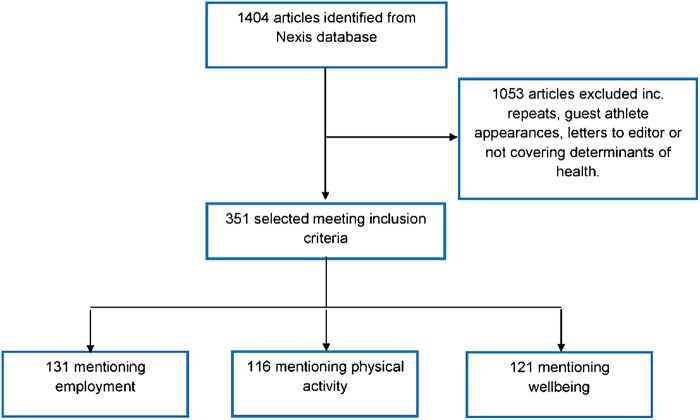

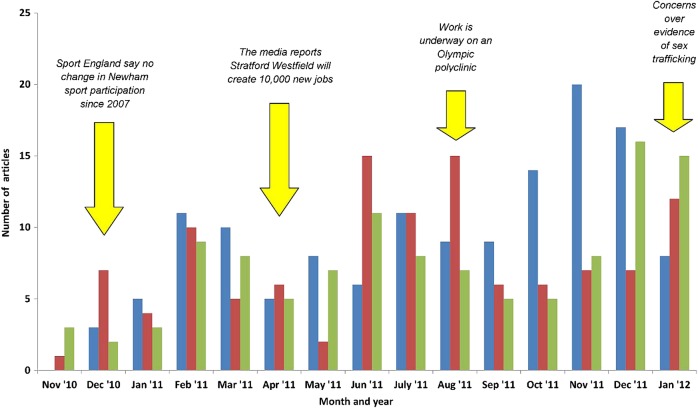

Three hundred and fifty-one articles met the inclusion criteria for this study. Figure 1 illustrates how these articles were split into coverage on the key determinants of health (some articles included content on more than one determinant and hence contribute to more than one pathway). In these included articles, there were 131 references to employment, 116 references to physical activity and 121 references to overall well-being. The frequency of articles reporting on both employment and well-being increased significantly over time (p=0.002 and 0.006, respectively); however, a non-significant increase was observed for physical activity (p=0.146), seen in figure 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included articles split into major determinants of health (some articles included relevant content on more than one pathway).

Figure 2.

The frequency of articles covering local issues on employment, physical activity and overall well-being relating to the Olympics over time.  =employment,

=employment,  =physical activity,

=physical activity,  =overall well-being. Pertinent media reports related to the determinants of health are aligned on the data line.

=overall well-being. Pertinent media reports related to the determinants of health are aligned on the data line.

A quantitative summary of the key themes of pathways to impact taken from the framework analysis can be seen in table 2. Coverage of new employment opportunities and the promotion of physical activity in young people received the majority of the media attention (162 of 351 articles covered these pathways). The vast majority of the articles took a positive perspective on the Olympic Games being hosted in Newham with less than 10% (32/351) addressing potential adverse effects.

Table 2.

Key themes related to pathways of impact on health brought about by the 2012 Olympic Games mentioned in local newspaper articles

| Number of times mentioned (%) | |

|---|---|

| Employment (131 articles) | |

| The creation of new opportunities for paid work in the local area | 81 (62) |

| Education initiatives in the local population to help find employment | 23 (18) |

| Employment created by activities related to building new homes in Newham | 19 (15) |

| Initiatives targeted specifically at assisting young people into paid work | 12 (9) |

| Stories covering issues related to difficulties in finding employment | 8 (6) |

| New paid employment created as a result of converting the Olympic infrastructure after the games | 8 (6) |

| Non-paid volunteering and work experience opportunities | 7 (5) |

| Commercial success in Newham that is expected to lead to the generation of future employment opportunities | 4 (3) |

| Grants awarded to local business ventures to expand their operations and employ more people | 3 (2) |

| Physical activity (116 articles) | |

| Initiatives with the aim of promoting physical activity in young people | 81 (70) |

| Initiatives with the aim of promoting physical activity all other age groups | 54 (47) |

| Stories related to how the built Olympic infrastructure and facilities could be used to promote physical activity after the Games | 16 (14) |

| Promotion of the Olympics as a sporting spectacle and how such ‘mega events’ can relate to exercise behaviour | 12 (10) |

| Stories covering issues related to how the Games might be related to negative outcomes in physical activity opportunities in the future | 9 (8) |

| Work by charitable organisations to promote physical activity in Newham | 6 (5) |

| Initiatives or events to promote physical activity which are facilitated by non-paid local volunteers | 6 (5) |

| Initiatives or events to promote physical activity targeted at people with disabilities | 4 (3) |

| Overall well-being (121 articles) | |

| Stories covering issues concerning the mental well-being in the people of Newham and community spirit | 27 (22) |

| Stories covering issues concerning the mental well-being of young people specifically | 25 (21) |

| Local issues related to crime, security and safety in Newham | 25 (21) |

| Stories related to how the built Olympic infrastructure and facilities could be used to promote overall well-being after the Games | 17 (14) |

| Stories covering issues related to how the Games might be related to negative outcomes in well-being | 15 (12) |

| Issues related to the provision of clinical care and health services for the local population | 15 (12) |

| Work by charitable organisations to promote health and well-being | 13 (11) |

| Projects dedicated to the provision of social housing for Newham | 7 (6) |

| Initiatives or events to promote overall well-being which are facilitated by non-paid local volunteers | 6 (5) |

| Stories related to the promotion of good nutrition and healthy living | 4 (3) |

Employment

The most frequently reported pre-Games pathway for health impact was via employment with the large majority of coverage around new job opportunities (see table 2). The New Westfield Shopping complex has been regularly cited as being one of the largest drivers of new employment opportunities in the area:

Westfield Stratford City is to create 10 000 permanent jobs when it opens in September…without the games, this level of investment and job creation would not be happening… (Newham Recorder, 13th April 2011).

However, reporting of the specifics of how many of these opportunities are likely to be eventually filled by local people in Newham, reveals that a smaller number of opportunities might be available to the local population.

A bit of badly needed Christmas cheer—40 new jobs have been created in Newham with a £750 000 investment to transform two McDonald's restaurants. (Newham Recorder, 8 December 2010).

A new hotel opening next to the ExCeL centre in the Docklands will create 66 new jobs, around 40 of them going to people who live in Newham…with east London seeing much regeneration ahead of the 2012 Olympic Games, the hotel is perfectly situated within easy reach of the Olympic Park, Westfield Stratford City and the 02. (Newham Recorder, 12 October 2011).

This discrepancy has not gone unnoticed in local media with a small number of articles raising concerns about whether the new employment opportunities would primarily benefit local residents and how sustainable this employment might in the post-Games environment:

Young people in the East End face becoming the ‘lost generation’ as shocking new figures show East London has the highest level of youth unemployment in London…the area (Newham) faces a legacy of wasted talent and abandoned hopes among its youth….Week after week I (Rushanara Ali, MP for Bethnal Green and Bow) hear stories from young people who want to work and have the skills to be successful in employment, yet cannot find work. (The Docklands and East London Advertiser, 13 October 2011).

Physical activity

Promotion of sport and exercise in young people were the most frequently cited pathways by which improvements in physical activity might occur (see table 2). These stories commonly described short-term initiatives organised around ‘one off’ sporting events or the promotion of existing facilities.

…the recent six-day Inter-College Sports Festival…has been granted the badge of the London 2012 Inspire Programme, which recognises innovative and exceptional projects directly inspired by the 2012 Games. (Newham Recorder, 8 November 2011)

…Gold challenge also sets out to raise £20 m for charity. Those who raise the most, a number of schools and people selected by ballot will take part in 100 m or 4X100 m races…it would be a ‘fitting way to say thank you to those who have been inspired by the Games to get active and raise money for charity. (Newham Recorder, 9 November 2011)

Positive stories about the potential of the Olympics to improve physical activity were very common. However, concerns about the ability of these initiatives to deliver meaningful behaviour change were much less frequently discussed. Reports from the results of a major national survey suggest pre-Olympic investment has had little impact on the proportion of Newham adults currently meeting physical activity guideline recommendations.20

Despite receiving extra cash to promote sport in the run-up to the Olympic Games, only 12.6 per cent of people over 16 get 30 min of moderate exercise a week. The Active People survey, carried out every three months by Sport England, showed that there had been no change in sports participation in the area (Newham) since 2007. In recent months, sports charities such as Access Sport and Fight for Peace have received £80 000 and £150 000 respectively and £30 000 each was donated to Star Park, Star Lane, Canning Town and West Ham Park to build multiuse games areas. Across London, mayor Boris Johnson has invested a total of £5.4 million, allocated by the Olympic Sports Legacy Programme, to promote an active, healthy lifestyle. Sport England's chief executive, Jenny Price, said that ‘a number of major sports have yet to deliver, despite significant levels of investment.’ (Newham Recorder, 29 December 2010)

Well-being

Unlike employment and physical activity, pathways of impact regarding well-being were heterogeneous, covering issues ranging from safety and security, health resource infrastructure, to charity work and community spirit (see table 2). However, only four articles out of the 351 linked the Olympic Games to issues relating to the promotion of good nutrition.

Young people from the University of East London and Newham Further Education College officially launched an initiative in front of 20 000 people at the 02 Arena to stop people from committing violence of any kinds to bring peace to the community… they decided to create a brand concept based on the Olympic ideals of courage, equality, respect, friendship and determination to encourage others to reject all forms of violence. (Newham Recorder, 19 October 2011).

The future of the Olympic Village has been decided…Work is underway on a polyclinic including multiple GP surgeries, outpatient activity and a children's clinic which will service the area, creating new medical jobs. (Newham Recorder, 17 August 2011)

Schools throughout the borough are invited to create a British dish worthy of an Olympic athlete. The recipe will represent everything great about British food while providing enough nourishment to spur our sportsmen on to glory. (Newham Recorder, 15 June 2011)

In parallel with employment and physical activity pathways, potential adverse effects of the Olympic Games received much less attention:

A seminar is being organised to look into evidence of sex trafficking in cities staging Olympic Games. Organisers say little is heard about women's safety and the threat of a rise in sexual exploitation and trafficking once the spectators return home. (The Docklands and East London Advertiser, 19 January 2012).

Discussion

Although the relationship is complex, the media has been previously described as ‘highly influential’10 in shaping discourses around health. The primary finding of this content analysis is that pre-Games reporting of the impact on health and the determinants of health increased over time, and is overwhelmingly positive. Much less attention is devoted to understanding the uncertainties and potential adverse effects, despite some concerns being raised. This is particularly important finding of this research as the scientific evidence around socioeconomic impacts of Olympic regeneration is mixed, with both positive and negative outcomes reported. Inadequate planning, poor stadium design, the withdrawal of sponsors, political boycotts, heavy cost overruns on facilities, the forced eviction of residents living in areas wanted for development and subsequent unwanted stadia can tarnish the Olympic legacy.27

This content analysis of pathways and impacts considered relevant media coverage taken from two local newspapers; however, we did not examine other potentially relevant local sources of information, for example, magazines, websites, regional television news which may have included useful counter-perspectives on hosting the 2012 Games. Information taken from media sources should be judged in the context of relevant biases such as deliberately polarising or divisive news stories that might be published in order to stimulate interest and readership numbers. Furthermore, inferences about the scope of the Olympic legacy are best considered in conjunction official government statistics, regional public health reports and dedicated research initiatives where applicable after the 2012 Games. A framework analysis has been used here because of its suitability for exploring issues of policy and also because the prime concern of this approach is to describe and interpret what is happening in a particular setting.24 However, an avenue for future enquiry aiming to investigate the broader societal and political context of these news stories, and the issues of interest that may have shaped their content, would be to undertake an explicitly discourse analytical approach. However, due to limitations of time and resource, such an approach was beyond the scope of the current study.

Despite a significant trend in increasing numbers of articles reporting on employment issues related to the Games, and a strong and consistent legacy theme of new employment opportunities for the local population, there is much less attention given to concerns over the number of new jobs generated for people in Newham. Local political leaders and young people's charities such as ‘Step Forward’ have voiced concerns that employment opportunities for young people are not being realised despite over half a decade of pre-Olympic investment in the local area. Indeed, the process of Olympic regeneration typically lacks transparency and is characterised by top-down decision making and a lack of consultation in conjunction with low-income and disadvantaged groups.6 Previous analyses have advocated a community-centred regeneration strategy,4 6 28 one that takes a bottom-up approach based on local needs and participation. Therefore, as part of a robust evaluation of the 2012 London Games legacy, it will be important to critically analyse official government employment figures for Newham regarding new employment opportunities undertaken and the sustainability of these positions.

Increasing grass roots sporting participation and improving national levels of physical activity behaviour was a key commitment made by the UK coalition Government as part of hosting the 2012 Olympics. Newham has high childhood obesity rates and poor engagement in physical activity. Sporting ‘mega events’ are typically framed as ‘a unique opportunity to improve public health’.29 Our results show that although local newspaper coverage on promotion of physical activity did not significantly increase over time, there were a large proportion of articles related to promoting physical activity in young people. However, despite sporting ‘mega events’ often being framed as a catalyst for improving population physical activity levels, especially for children and young people, there is little evidence to indicate that individual participation and physical activity rates actually increase.30 Rather, it is improvements in the physical activity-related infrastructure (associated with the events) that are taken as indicative of greater participation.31 In fact, the provision of new sports facilities were found to benefit elite athletes after events more than the host population.5 In a systematic review of the impact of sporting ‘mega events’ upon physical activity and sports participation the authors found that there was mixed evidence for a ‘demonstration’ or ‘trickle down’ effect on participation.30 No direct link was found between elite events and community participation in physical activity, which contradicts assumptions about the Games ‘inspiring’ local people to take part in sporting activities and exercise. This would seem to be reflected in the Sport England data which reports that just 12.6% of people over 16 in Newham get 30 min of moderate exercise a week. Community and social capital are potentially important in empowering communities and improving individual and collective self-efficacy,5 which may over time, contribute to behaviour change.32 33 This finding lends further support to the argument for community-centred regeneration28 to address the needs and support of local people.

Reporting of pathways to increasing well-being significantly increased over time although (because of the multifaceted nature of ‘well-being’) they were intuitively heterogeneous. However, beneficial impacts on community spirit were particularly prominent. These impacts tended to be focused on individually driven initiatives that appear to occur more from a collective sense of (possibly transient) opportunistic altruism, rather than directly facilitated by Olympic investment brought to the area. Financial investment may have other direct benefits such as the Olympic polyclinic. It has been asserted by the chief medical officer for the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, that the Olympic polyclinic will be the ‘most tangible health legacy from the 2012 games’.34 However, the Chief Executive of North and East London NHS has indicated uncertainty over whether the cutting edge medical equipment that will be used for delivering world-class medical care for the elite athletes will remain in the clinic after the Games.35 The true nature and potential for beneficial health impacts on the local population that can be gained through just one more (possibly downgraded) health clinic is an area of significant uncertainty.

Conclusions

Local media coverage of the pre-Games pathways and impact on health in the host borough of Newham is overwhelmingly positive. However, specific uncertainties around the true nature of its impact on local employment and physical activity were articulated. Evaluation of the tangible impacts on population health, and the determinants of health and health inequalities, of the London 2012 Olympics is required in order to unpack whether there is truly a lasting legacy for East London.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Trisha Greenhalgh for her input on manuscript drafting and Dr Miland Joshi for statistical assistance. Professor Steven Cummins is supported by a National Institute of Health Research Senior Fellowship.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS, LB, ST and SC contributed to the study design. MS conducted data collection. MS and LB conducted the thematic analysis and LB conducted the linear regression. All authors contributed to interpretation of results and manuscript drafting.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Article data set available from the corresponding author at l.bourke@qmul.ac.uk.

References

- 1.NHS Newham Joint strategic seeds Assessment, Newham. 4 November 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meegan R, Mitchell A. ‘It's not community round here, it's neighbourhood’: neighbourhood change and cohesion in urban regeneration. Urban Stud 2001;38:2167–94 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poortinga W. Community resilience and health: The role of bonding, bridging, and linking aspects of social capital. Health Place 2012;18:286–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misener L, Mason DS. Creating community networks: can sporting events offer meaningful sources of social capital? Manag Leisure 2006;11:39–56 [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCartney G, Thomas S, Thomson H, et al. The health and socioeconomic impacts of major multi-sport events: systematic review (1978–2008). BMJ 2010;340:c2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherer J. Olympic villages and large-scale urban development: crises of capitalsim, deficits of democracy? Sociology 2011;45:782–97 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennelly J, Watt P. Sanitizing public space in Olympic host cities: the spatial experiences of marginalized youth in 2010 vancouver and 2012 London. Sociology 2011;45:765–81 [Google Scholar]

- 8.HM Government Public Accounts Committee—Seventy Fourth Report. Preparations for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games 2012. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmpubacc/1716/171602.htm (accessed 12 Jun 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller J. News values: ideas for an infromation Age. Chicago: The Univeristy of Chicago Press, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewison G, Tootell S, Roe P, et al. How do the media report cancer research? A study of the UK's BBC website. Br J Cancer 2008;99:569–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seale C. Health and the media. Malden, Oxford: Blackwell, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. News media coverage of smoking and health is associated with changes in population rates of smoking cessation but not initiation. Tob Control 2001;10:145–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department for Culture Media and Sport Before, during and after. Making the most of the London 2012 Games, 2008

- 14.Department of Health On the state of public health: annual report of the chief medical officer 2009, 2010

- 15.Cameron D.2010. http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/pm-speech-on-well-being/ (accessed 12 Jun 2012)

- 16.Greater London Authority Olympic Park Legacy Corporation: Proposals by the Mayor of London for public consultation. 2011. http://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/oplc-mayor-proposals.pdf (accessed 12 Jun 2012)

- 17.Wellings K, Datta J, Wilkinson P, et al. The 2012 Olympics: assessing the public health effect. Lancet 2011;378:1193–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post 2010. London, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weed M, Coren E, Fiore J, et al. Developing a physical activity legacy from the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: a policy-led systematic review. Perspect Public Health 2012;132:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health Physical Activity Health Improvement and Protection Start Active, Stay Active: A report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers, 2011

- 21.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res 1999;34:215–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins J, Green SP. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alkhateeb S, Lawrentschuk N. Consumerism and its impact on robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2011;108:1874–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. London: Routledge, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilton S, Hunt K. UK newspapers’ representations of the 2009–10 outbreak of swine flu: one health scare not over-hyped by the media? J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:941–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gold JR, Gold MM. Olympic cities: regeneration, city rebranding and changing urban agendas. Geography Compass 2008;2:300–18 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane G. Literature review: olympic venues—regeneration legacy. In: Brownill S, ed. Oxford: London Assembly, 2010. http://planning.brookes.ac.uk/staff/resources/Olympic%20Venues%20Report.pdf (accessed 12 Jun 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs B, Dutton C. Social and community issues. In: Roberts P, Sykes H, eds. Urban regeneration. London: Sage, 2000. pp 109–26 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weed M, Coren E, Fiore J, et al. A systematic review of the evidence base for developing a physical activity and health legacy from the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. London: Department of Health, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy NM, Bauman A. Mass sporting and physical activity events: are they bread and circuses or public health interventions to to increase population levels of physical activity? J Physical Activity Health 2007;4:193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, et al. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport 1992;63:60–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King TK, Marcus BH, Pinto BM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral mediators of changing multiple behaviors: smoking and a sedentary lifestyle. Prev Med 1996;25:684–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torjesen I. Olympic site polyclinic ‘will be most tangible health legacy’ of games, says medical chief. BMJ 2012;344:e4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercer K. Polyclinic for London Olympics athletes unveiled http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-18498520, BBC News, London, 18 Jun 2012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.