Abstract

Objective

To compare the clinical and procedural characteristics of emergency hospital admissions for drug poisoning and major diseases.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

Discharged patients from 855 acute care hospitals from 1 July to 31 December in 2008 in Japan.

Results

There were a total of 1 157 893 emergency hospital admissions. Among the top 100 causes, drug poisoning was ranked higher in terms of the percentage of patients using ambulance services (74.1%; second) and tertiary emergency medical services (37.8%; first). Despite higher utilisation of emergency care resources, drug poisoning ranked lower in terms of the median length of stay (2 days; 100th), percentage of requirement for surgical procedures (1.7%; 91st) and inhospital mortality ratio (0.3%; 74th).

Conclusions

Drug poisoning is unique among the top 100 causes of emergency admissions. Our findings suggest that drug poisoning imposes a greater burden on emergency care resources but has a less severe clinical course than other causes of admissions. Future research should focus on strategies to reduce the burden of drug poisoning on emergency medical systems.

Keywords: Suicide & self-harm < Psychiatry, Epidemiology, Health Services Administration & Management

Article summary.

Article focus

Only a few multicentre studies have compared resource use and clinical course of emergency hospital admissions.

Our aim was to compare the clinical and procedural characteristics of emergency hospital admissions for drug poisoning and major diseases by using a nationwide administrative discharge database.

Key messages

Drug poisoning is in an anomalous position among the top 100 causes of emergency admissions.

Patients with drug poisoning had a less severe clinical course than those with other causes, although they had higher utilisation of emergency care resources.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Large data from a nationwide discharge database were studied.

Our results are limited to inpatient admissions to acute care hospitals.

Introduction

A better understanding of epidemiology in emergency medical services (EMS) is important for planning EMS resource use and EMS personnel training needs.1 Drug poisoning is a major cause of admissions to acute care hospitals and places a considerable burden on EMS resources. Drug poisoning accounts for over 15% of all admissions to intensive care units.2 3 However, most cases of drug poisoning do not result in clinical toxicity. Of patients with drug poisoning admitted to an intensive care unit, 91% do not require advanced treatments.2 Over 75% of patients admitted to emergency departments can be released from medical observation after a brief period (ie, 1–2 days).4–6 Less than 1% of cases result in mortality.7 8 These previous studies suggest that drug poisoning may impose a needless burden on high-level EMS despite their limited requirements for advanced treatments.2 9

Although a number of studies have examined the detailed epidemiology of drug poisoning,2–8 only a few multicentre studies have compared resource use and clinical course of emergency hospital admissions.10–12 It remains unknown as to whether drug poisoning imposes a greater burden on emergency care resources and has a less severe clinical course among major causes of admissions. We thus aimed to compare the clinical and procedural characteristics of emergency hospital admissions for drug poisoning and major diseases by using a nationwide administrative discharge database.

Methods

Data source

We conducted an observational study using the nationwide discharge administrative database of the Diagnosis Procedure Combination/Per-Diem Payment System (DPC/PDPS), a Japanese case-mix classification system launched in 2002 by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.13 Every year, the DPC Research Group conducts a survey of DPC/PDPS hospitals. In 2008, 855 of 1558 DPC/PDPS hospitals voluntarily participated in the survey. The DPC/PDPS database includes clinical and procedural information on all inpatients discharged from the participating hospitals between 1 July and 31 December. All the data for each patient were recorded at discharge. The database includes 2.86 million admissions, representing approximately 40% of all inpatient admissions to acute care hospitals in Japan (excluding psychiatric and tuberculosis hospitals).14 In the present study, we included all emergency hospital admissions and excluded planned admissions to the DPC/PDPS hospitals.

Setting

In Japan, the EMS system is divided into three categories:15 (1) primary EMS that provides care to patients who can be discharged without hospitalisation; (2) secondary EMS that provides care to patients who require admission to a regular inpatient bed and (3) tertiary EMS that provides care to severely ill and trauma patients who require intensive care. In 2008, there were 18 892 clinics and 963 hospitals for primary EMS, 3053 hospitals for secondary EMS, and 214 hospitals for tertiary EMS.14 In the present study, we focused on secondary and tertiary EMS rather than primary EMS, because the DPC/PDPS database is an inpatient database. Among the 855 participating hospitals in the DPC/PDPS database, 725 provide only secondary EMS and the other 130 provide tertiary EMS. Although some of the participating hospitals also provide primary EMS, data on emergency outpatient admissions are not included in the database.

Clinical and procedural characteristics

To describe clinical and procedural characteristics of emergency hospital admissions, we used the following study variables: (1) age; (2) gender; (3) major disease categories; (4) comorbidities at admissions; (5) level of consciousness assessed by the Japan Coma Scale (JCS);16 (6) use of ambulance service; (7) use of tertiary EMS; (8) requirement for surgical procedures that include both major surgery and suturing in an emergency department; (9) length of stay (days) and (10) inhospital mortality.

Physicians recorded information on diagnoses using the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) codes. According to the ICD-10 codes, 506 major disease categories were defined in 2008 (see online supplementary table S1). In the database, patients with drug, chemical and unspecified poisoning (ICD-10 codes T360–T509, T510–T659 and T887, respectively) have the same major disease code (disease code 161070). In the present study, we modified the disease code to separate drug poisoning (modified disease code 161070a) from chemical and unspecified poisoning (modified disease code 161070b) according to their ICD-10 codes.

In the database, up to four diagnosed comorbidities per patient were recorded. Using the criteria developed by the Global Burden of Disease study with some modifications,17 we defined comorbid status of mental illness as being diagnosed with any of the following ICD-10 codes: unipolar depressive disorders (F32–F33); bipolar affective disorder (F30–F31); schizophrenia (F20–F29); alcohol use disorders (F10); drug use disorders (F11–F16 and F18–F19); post-traumatic stress disorder (F431); obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42); panic disorder (F400 and F410) or insomnia (F51).

Statistical analyses

First, we conducted univariate analyses to summarise the clinical and procedural characteristics of all emergency admissions. Second, we selected patients diagnosed with one of the top 100 major disease codes and calculated summary statistics of 8 variables by disease code. These variables were as follows: (1) percentage of patients aged 65 years or older; (2) percentage of patients comorbid with mental illness; (3) percentage of patients admitted to hospitals with deep coma (JCS scores ≥100, corresponding to scores of ≤7 on the Glasgow Coma Scale);16 (4) percentage of patients using ambulance services; (5) percentage of patients using tertiary EMS; (6) percentage of patients requiring surgical procedures; (7) median length of stay and (8) percentage of inhospital mortality. To maximise interpretability, we restricted this analysis to patients with 1 of the top 100 causes of admissions. We used a predictive principal component analysis (PCA) biplot to reduce the dimensionality of multivariate data (ie, 100 causes of admissions×8 variables) and then to visualise two dimensions with minimal loss of information.18 Before conducting the predictive PCA biplot, we standardised each variable with a mean of 0 and a SD of 1 because the measurement units of 8 variables were incommensurable. In the predictive PCA biplot, the 8 variables were represented by 8 biplot axes to read off predictive values of the variables for each of the top 100 causes. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 2.14.119 The predictive PCA biplot was performed using the BiplotGUI package under R.19

Results

Characteristics of all emergency hospital admissions

During the study period, there were a total of 1 157 893 emergency hospital admissions to 855 hospitals. Characteristics of these admissions are presented in table 1. The majority (51.7%) of admissions were for patients aged ≥65 years. Patients aged 0–14 years accounted for less than one-sixth (15.3%) of the admissions. The most prevalent diagnosis was pneumonia, accounting for 10.2% of all admissions, followed by stroke (5.5%) and heart failure (2.8%). Drug poisoning ranked 41st among causes of admissions. Less than 5% of patients used tertiary EMS. Of those patients, 88.3% stayed for more than 3 days. About 7% of patients died during hospitalisation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of emergency hospital admissions

| Characteristic | N of admissions | Percentage of admissions | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 0–14 | 177 092 | 15.3 | 15.2 to 15.4 |

| 15–64 | 382 025 | 33.0 | 32.9 to 33.1 |

| ≥65 | 598 776 | 51.7 | 51.6 to 51.8 |

| Gender women | 547 280 | 47.3 | 47.2 to 47.3 |

| Top 10 causes of admissions and drug poisoning (disease code) | |||

| 1. Pneumonia, acute bronchitis, acute bronchiolitis (040080) | 117 649 | 10.2 | 10.1 to 10.2 |

| 2. Stroke (010060) | 63 931 | 5.5 | 5.5 to 5.6 |

| 3. Heart failure (050130) | 32 993 | 2.8 | 2.8 to 2.9 |

| 4. Intestinal obstruction without hernia (060210) | 28 701 | 2.5 | 2.5 to 2.5 |

| 5. Fracture of proximal femur (160800) | 25 905 | 2.2 | 2.2 to 2.3 |

| 6. Viral enteritis (150010) | 24 920 | 2.2 | 2.1 to 2.2 |

| 7. Asthma (040100) | 23 858 | 2.1 | 2.0 to 2.1 |

| 8. Angina pectoris, chronic ischaemic heart disease (050050) | 20 775 | 1.8 | 1.8 to 1.8 |

| 9. Disorder associated with shortened gestation period or low birth weight (140010) | 20 540 | 1.8 | 1.8 to 1.8 |

| 10. Renal infection (110310) | 19 853 | 1.7 | 1.7 to 1.7 |

| 41. Drug poisoning (161070a) | 6748 | 0.6 | 0.6 to 0.6 |

| Other causes | 769 326 | 66.4 | 66.4 to 66.5 |

| Comorbid mental illness | 23 279 | 2.0 | 2.0 to 2.0 |

| Deep coma | 26 792 | 2.3 | 2.3 to 2.3 |

| Ambulance services | 311 333 | 26.9 | 26.8 to 27.0 |

| Tertiary EMS | 54 938 | 4.7 | 4.7 to 4.8 |

| Surgical procedures | 321 974 | 27.8 | 27.7 to 27.9 |

| Length of stay (days) | |||

| ≤3 | 135 096 | 11.7 | 11.6 to 11.7 |

| 4–7 | 266 651 | 23.0 | 23.0 to 23.1 |

| 8–14 | 296 549 | 25.6 | 25.5 to 25.7 |

| 15–30 | 258 717 | 22.3 | 22.3 to 22.4 |

| 31–60 | 136 014 | 11.7 | 11.7 to 11.8 |

| ≥60 | 64 866 | 5.6 | 5.6 to 5.6 |

| Death during hospitalisation | 78 226 | 6.8 | 6.7 to 6.8 |

Comorbidity of mental illness was defined as the following ICD-10 codes as comorbidities: unipolar depressive disorders (F32–F33), bipolar affective disorder (F30–F31), schizophrenia (F20–F29), alcohol use disorders (F10), drug use disorders (F11–F16 and F18–F19), post-traumatic stress disorder (F431), obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42), panic disorder (F400 and F410), or insomnia (F51). Deep coma was defined as a score on the Japan Soma Scale of 100 or more.

EMS, emergency medical services.

Comparison of drug poisoning and major diseases

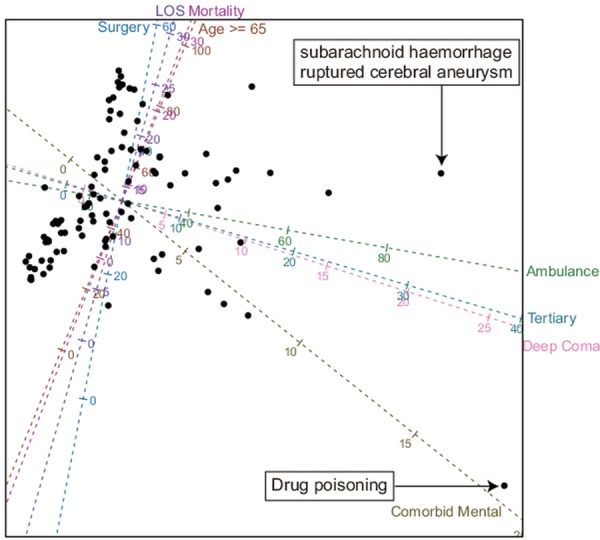

The top 100 causes of admissions covered 83% (965 749 admissions) of all admissions. Characteristics by cause of admission are shown in table 2 for the top 10 causes and drug poisoning; the top 100 causes are also shown in online supplementary table S1. The predictive PCA biplot with two dimensions accounts for 62.9% of the variance in the data from the top 100 causes. The predictive PCA biplot revealed that drug poisoning was in a unique position (figure 1). Among the top 100 causes, patients with drug poisoning were less likely to be aged ≥65 years (13.4%; 86th) and most likely to be diagnosed with mental illness (33.7%; first). In addition, patients with drug poisoning were more likely to be admitted to hospitals with deep coma (26.2%; second), more likely to use ambulance services (74.1%; second) and most likely to use tertiary EMS (37.8%; first). Despite the higher utilisation of emergency care resources, clinical course of drug poisoning was less severe. Among the top 100 causes, patients with drug poisoning had the shortest median length of stay (2 days; 100th), were less likely to require surgical procedures (1.7%; 91st), and were less likely to die during hospitalisation (0.3%; 74th).

Table 2.

Characteristics of poisoning and other causes of admissions

| Rank | Top 10 causes of admissions and drug poisoning (disease code) | Clinical and procedual characteristics, %/median, (rank) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-10 codes | N | Percentage | Age ≥65 | Comorbid mental | Deep coma | Ambulance | Tertiary | Surgery | LOS | Mortality | ||

| 1 | Pneumonia, acute bronchitis, acute bronchiolitis (040080) | A370, A378, A379, A481, B012, B052, B371, B59, J13, J14, J15*, J16*, J17*, J18*, J20*, J21*, J22, J69* | 117 649 | 10.2 | 48.7 (57) | 1.5 (53) | 2.2 (23) | 19.3 (53) | 2.2 (43) | 5.7 (82) | 9.0 (62) | 7.9 (29) |

| 2 | Stroke (010060) | G45*, G46*, I63*, I65*, I66*, I675, I679, I693, I978 | 63 931 | 5.5 | 77.8 (11) | 1.5 (53) | 4.0 (14) | 44.1 (21) | 8.0 (21) | 8.0 (77) | 17.0 (30) | 5.2 (35) |

| 3 | Heart failure (050130) | I50* | 32 993 | 2.8 | 86.0 (4) | 1.3 (60) | 1.6 (26) | 34.3 (27) | 9.3 (19) | 11.5 (67) | 18.0 (27) | 11.1 (24) |

| 4 | Intestinal obstruction without hernia (060210) | K560, K562, K563, K564, K565, K566, K567, K913 | 28 701 | 2.5 | 64.3 (33) | 1.9 (40) | 0.2 (68) | 18.1 (59) | 2.0 (48) | 19.3 (57) | 11.0 (51) | 2.4 (48) |

| 5 | Fracture of proximal femur (160800) | M2435, M2445, S7200, S7210, S7220, S7230, S7270, S7280, S7290, S730 | 25 905 | 2.2 | 90.6 (1) | 3.7 (9) | 0.1 (75) | 49.5 (14) | 1.5 (58) | 91.0 (5) | 30.0 (2) | 1.4 (58) |

| 6 | Viral enteritis (150010) | A08*, A09 | 24 920 | 2.2 | 23.4 (80) | 0.9 (73) | 0.1 (75) | 14.9 (67) | 0.3 (87) | 0.8 (95) | 5.0 (89) | 0.2 (79) |

| 7 | Asthma (040100) | J45*, J46 | 23 858 | 2.1 | 12.0 (87) | 0.8 (76) | 0.4 (52) | 9.5 (85) | 1.2 (64) | 0.5 (97) | 6.0 (82) | 0.3 (74) |

| 8 | Angina pectoris, chronic ischaemic heart disease (050050) | I20*, I25* | 20 775 | 1.8 | 68.2 (23) | 0.9 (73) | 0.4 (52) | 31.9 (31) | 7.7 (22) | 43.7 (29) | 7.0 (78) | 0.8 (64) |

| 9 | Disorder associated with shortened gestation period or low birth weight (140010) | P00*, P01*, P02*, P03*, P04*, P05*, P07*, P08*, P10*, P11*, P12*, P13*, P15*, P20*, P21*, P22*, P23*, P24*, P25*, P26*, P27*, P28*, P29*, P35*, P36*, P37*, P38, P39*, P50*, P51*, P52*, P53, P54*, P55*, P56*, P57*, P58*, P590, P591, P592, P593, P598, P599, P60, P61*, P70*, P71*, P72*, P74*, P75, P76*, P77, P780, P781, P782, P783, P789, P80*, P81*, P83*, P90, P91*, P92*, P93, P94*, P95, P96* | 20 540 | 1.8 | 0.0 (95) | 0.0 (98) | 0.4 (52) | 9.4 (86) | 0.0 (97) | 10.5 (71) | 8.0 (70) | 0.5 (69) |

| 10 | Renal infection (110310) | N10, N151, N390 | 19 853 | 1.7 | 63.7 (34) | 1.7 (44) | 1.1 (32) | 22.5 (47) | 1.3 (63) | 6.7 (80) | 10.0 (55) | 1.5 (56) |

| 41 | Drug poisoning (161070a) | T36*, T37*, T38*, T39*, T40*, T41*, T42*, T43*, T44*, T45* T46* T47* T48* T49* T50* | 6 748 | 0.6 | 13.4 (86) | 33.7 (1) | 26.2 (2) | 74.1 (2) | 37.8 (1) | 1.7 (91) | 2.0 (100) | 0.3 (74) |

Rankings were based on data from the top 100 causes of admissions. Comorbidity of mental illness was defined as the following ICD-10 codes as comorbidities: unipolar depressive disorders (F32–F33), bipolar affective disorder (F30–F31), schizophrenia (F20–F29), alcohol use disorders (F10), drug use disorders (F11–F16 and F18–F19), post-traumatic stress disorder (F431), obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42), panic disorder (F400 and F410) or insomnia (F51). Deep coma was defined as a score on the Japan Soma Scale of 100 or more.

Ambulance, ambulance services; LOS, median length of stay; mortality, in-hospital mortality; surgery, surgical procedures; tertiary, tertiary emergency medical services; *, wild card.

Figure 1.

The predictive principal component biplot on data from the characteristics of the top 100 causes. Each dot represents one of the causes. Eight axes are positioned and calibrated so that the orthogonal projection of a dot onto an axis ‘predicts’ as best as is graphically possible the value of the corresponding disease on the corresponding variable. Ambulance, ambulance services; LOS, median length of stay; mortality, inhospital mortality; surgery, surgical procedures; tertiary, tertiary emergency medical services.

In terms of the percentage of patients admitted to tertiary EMS, subarachnoid haemorrhage and ruptured cerebral aneurysm (disease code 010020) ranked second (30.3%; 2nd; see the 46th row in online supplementary table S1). Patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage and ruptured cerebral aneurysm were most likely to be admitted to hospitals with deep coma (33.9%; first) and most likely to use ambulance services (76.0%; first). They had a longer median length of stay (28 days; 4th), were more likely to require surgical procedures (73.2%; 11st) and were more likely to die during hospitalisation (26.9%; 9th).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that used a nationwide administrative discharge database to compare detailed clinical and procedural characteristics of emergency hospital admissions for drug poisoning and major diseases. We found that drug poisoning was unique among the top 100 causes of emergency admissions. Patients with drug poisoning had a less severe clinical course than those with other causes, although they had higher utilisation of emergency care resources. Our findings suggest that drug poisoning imposes a higher burden on emergency care resources than other causes of emergency admissions.

Our results are consistent with those of a case–control study conducted in Australia and New Zealand.10 That study found that the median length of stay in patients with drug poisoning was 3 days, which was much lower than the overall median length of stay (9 days) in patients with one of the eight most common diagnoses in a tertiary intensive care unit. One possible explanation for the potential over-utilisation of high-level EMS resources is that staff with significant experience in psychosocial assessment might be more available in high-level EMS facilities. In Japan, 85% of tertiary EMS hospitals have psychiatric departments, while 23% of secondary EMS hospitals are so equipped.14 Because most patients with drug poisoning have attempted suicide,20 and self-harm patients should receive a specialist psychosocial assessment according to the clinical guideline,21 patients with drug poisoning are transferred to high-level EMS in which mental health specialists are more available.

Another explanation for the potential overutilisation may relate to difficulties that confront ambulance officers. First, staff in secondary EMS hospitals might decline to manage patients with drug poisoning. A survey conducted in Osaka city revealed that ambulance officers contacted more hospitals to transport patients with drug poisoning than all patients (average number of contacted hospitals: 7.6 vs 1.8, respectively).22 Second, ambulance officers might transport patients with drug poisoning to high-level EMS because of their deep coma. Drug poisoning ranked within the top two in terms of the percentage of patients with deep coma and percentage of patients admitted to tertiary EMS. However, patients with drug poisoning had a less severe clinical course than those with other causes. For example, in terms of the percentage of patients admitted to tertiary EMS, drug poisoning ranked first, followed by subarachnoid haemorrhage and ruptured cerebral aneurysm, which had a much more severe clinical course than drug poisoning. It would be of great value to investigate triage tools predicting the need for advanced treatments based on information not only from early admission factors,23 but also from prehospital factors.24

Our study has several limitations. First, our results cannot be generalised and are limited to inpatient admissions to acute care hospitals rather than emergency outpatient admissions or emergency admissions to psychiatric hospitals, because we used the DPC/PDPS database. Second, we were unable to evaluate variables not included in the DPC/PDPS database. As a result, we could not assess other potentially important factors predicting the need for advanced treatments, such as acute physiology and chronic health evaluation scores at admission23 or clinical management and course during prehospital period.24 Third, we included all types of drug poisoning (ie, deliberate, accidental and undetermined intent) as in a previous study,7 because data on external causes (ICD-10 codes V01–Y98) are not recorded in the DPC/PDPS database. As a result, we could not distinguish between deliberate and accidental drug poisoning. Fourth, although the database included approximately 40% of all inpatient admissions in Japan, participation in the survey was voluntary for each hospital and the patient selection procedure was not based on a random sampling technique from all acute hospitals.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that drug poisoning is unique among the top 100 causes of emergency admissions. Future research should focus on strategies to reduce the burden of drug poisoning on emergency medical systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Toshie Noda for her feedbacks on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

Contributors: SM, KBI and KF conducted data collection, data synthesis and data management. KF and HI obtained funding. YO participated in study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript. SS supervised data analysis. SS, KBI, KF and HI participated in interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Funding for administrating the study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation (Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare H22-SEISAKU-SITEI-031 and H24-SEISAKU-SITEI-012). Funding for writing this article was supported by a Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (H22-IYAKU-IPPAN-013) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Platts-Mills TF, Leacock B, Cabanas JG, et al. Emergency medical services use by the elderly: analysis of a statewide database. Prehosp Emerg Care 2010;14:329–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwake L, Wollenschlager I, Stremmel W, et al. Adverse drug reactions and deliberate self-poisoning as cause of admission to the intensive care unit: a 1-year prospective observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:266–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath J. A survey of deliberate self-poisoning. Med J Aust 1989;150:317––18., 320–1, 324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson A, Wright M, Pond SM. Experience with 732 acute overdose patients admitted to an intensive care unit over 6 years. Med J Aust 1993;158:28–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrix L, Verelst S, Desruelles D, et al. Deliberate self-poisoning: characteristics of patients and impact on the emergency department of a large university hospital. Emerg Med J 2012. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollander JE, McCracken G, Johnson S, et al. Emergency department observation of poisoned patients: how long is necessary? Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:887–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heyerdahl F, Bjornaas MA, Dahl R, et al. Repetition of acute poisoning in Oslo: 1-year prospective study. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:73–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang Y, Zhao W, Xiang H, et al. ED visits for drug-related poisoning in the United States, 2007. Am J Emerg Med 2011;30:293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamad AE, Al-Ghadban A, Carvounis CP, et al. Predicting the need for medical intensive care monitoring in drug-overdosed patients. J Intensive Care Med 2000;15:321–8 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flabouris A, Hart GK, George C. Outcomes of patients admitted to tertiary intensive care units after interhospital transfer: comparison with patients admitted from emergency departments. Crit Care Resusc 2008;10:97–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiller HA, Singleton MD. Comparison of incidence of hospital utilization for poisoning and other injury types. Public Health Rep 2011;126:94–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadman MC, Muelleman RL, Coto JA, et al. The pyramid of injury: using ecodes to accurately describe the burden of injury. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42:468–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda S, Ishikawa KB, Kuwabara K, et al. Development and use of the Japanese case-mix system. Eurohealth 2008;14:25–30 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics and Information Department, Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2008 Summary of Static/Dynamic Surveys of Medical Institutions and Hospital Report (in Japanese). Tokyo: Health and Welfare Statistics Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japan International Cooperation Agency. Emergency medical care Japan's experiences in public Health and medical systems: towards improving public health and medical systems in developing countries. Tokyo: Institute for International Cooperation, Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2005:227–44 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeuchi E. Reliability of grading systems of impaired consciousness. Statistical evaluation of inter-rater reliability and validity of the Japan coma scale (JCS) (in Japanese). J Osaka Med Coll 1988:20–30 [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gower J, Lubbe S, Roux NL. Understanding biplots. West Sussex: Wiley, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Development Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirata K, Matsumoto Y, Tomioka J, et al. Acute drug poisoning at critical care departments in Japan. Jpn J Hosp Pharm 1998;24:340–8 [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Self-harm: the short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fire and Disaster Management Agency of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Reports on emergency medicine 2009, Tokyo, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eizadi Mood N, Sabzghabaee AM, Khalili-Dehkordi Z. Applicability of different scoring systems in outcome prediction of patients with mixed drug poisoning-induced coma. Indian J Anaesth 2011;55:599–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gwini SM, Shaw D, Iqbal M, et al. Exploratory study of factors associated with adverse clinical features in patients presenting with non-fatal drug overdose/self-poisoning to the ambulance service. Emerg Med J 2011;28:892–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.