Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association between anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents and their families and later medical benefit receipt in young adulthood.

Design

Prospective cohort study. Norwegian population study linked to national registers.

Participants

Data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study 1995–1997 (HUNT) gave information on anxiety and depression symptoms as self-reported by 7497 school-attending adolescents (Hopkins Symptoms Checklist—SCL-5 score) and their parents (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score). There were 2711 adolescents with one or more siblings in the cohort.

Outcome measures

Adolescents were followed for 10 years in national social security registers, identifying long-term receipt of medical benefits (main outcome) and unemployment benefits for comparison from ages 20–29.

Methods

We used logistic regression to estimate OR of benefit receipt for groups according to adolescent and parental anxiety and depression symptom load (high vs low symptom loads) and for a one point increase in the continuous SCL-5 score (range 1–4). We adjusted for family-level confounders by comparing siblings differentially exposed to anxiety and depression symptoms.

Results

Comparing siblings, a one point increase in the mean SCL-5 score was associated with a 65% increase in the odds of medical benefit receipt from age 20–29 (adjusted OR, 1.65, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.48). Parental anxiety and depression symptom load was an indicator of their adolescent's future risk of medical benefit receipt, and adolescents with both parents reporting high symptom loads seemed to be at a particularly high risk. The anxiety and depression symptom load was only weakly associated with unemployment benefits.

Conclusions

Adolescents in families hampered by anxiety and depression symptoms are at a substantially higher risk of medical welfare dependence in young adulthood. The prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression in adolescence should be family-oriented and aimed at ensuring work-life integration.

Keywords: Public Health, Epidemiology, Anxiety and depression, Adolescents, Social insurance, Family

Article summary.

Article focus

The influence of anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescence on work integration in early adulthood, assessed by the receipt of long-term medical benefits from age 20 to 29.

The impact of parental anxiety and depression on adolescents’ future risk of medical benefit receipt.

Key messages

Adolescents with high levels of anxiety and depression symptoms had increased risk of receiving medical benefits from age 20 to 29.

Confounding from family factors was not a likely explanation as associations were present among siblings differentially exposed to anxiety and depression.

High parental levels of anxiety and depression symptoms were associated with an increased risk of medical benefit receipt from age 20 to 29 in adolescent offspring.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Large data material consisting of both adolescent and parental health variables combined with almost complete information on outcome measures from National registers.

Self-reported data only.

Results could be dependent on characteristics of the labour market and welfare regime.

Introduction

Anxiety and depression are leading contributors to global disability and disease burden among young people, and adolescents with symptoms of anxiety and depression are more likely to experience mental health problems in adulthood,1–4 educational underachievement and periods of unemployment later in life.3–5 However, research on anxiety and depression and later life outcomes related to working life has mostly been geared towards adult working populations.6 7 Furthermore, such studies have not considered life course and family perspectives.

Anxiety and depression in parents and their offspring are associated due to both heritage and influences on the parenting role and family environment.8–12 Factors that are shared within families, such as socioeconomic status, marital conflict, parenting style and stressful life events may confound associations between symptoms of anxiety and depression and life outcomes in young people.13–15 Therefore, a prospective design comparing siblings with different symptom loads would be suitable, as it will in itself control for shared factors that could have confounded the results of other studies.16

Our first and main aim was to study the relationship between anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescence and later receipt of medical benefits in young adulthood. Our second aim was to assess this relationship by comparing levels of anxiety and depression symptoms within sibling groups, while our third aim was to study the relationship between the combined anxiety and depression symptom loads of adolescents and parents and later receipt of medical benefits in young adult offspring. For comparative purposes, we also wanted to explore these associations using receipt of unemployment benefits as an alternative outcome.

Methods

Data and linkages

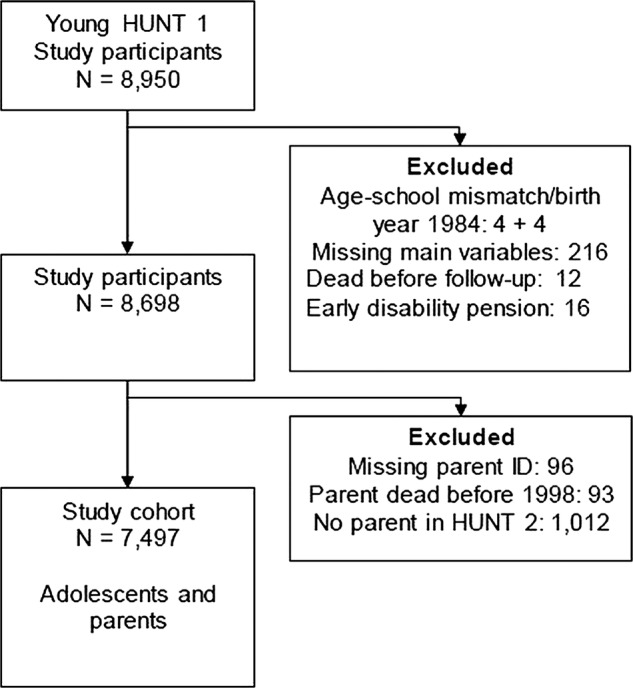

We used data from the HUNT study, a Norwegian population study from Nord-Trøndelag County (http://www.ntnu.no/hunt/english),17 where 8950 school-attending adolescents (90% of those invited) completed a questionnaire between 1995 and 1997 (the Young-HUNT Study). We linked the adolescent data to the National Education and National Insurance Administration Registers for information on demography and the receipt of social benefits during follow-up from 1998 to 2008 (Statistics Norway, http://www.ssb.no/en/). Biological parents and siblings were identified through a linkage to the Norwegian Family Register using a unique parental identification number for siblings. Included in our study cohort was the 7497 eligible adolescents with one or two parents who had participated in the HUNT 2 survey (1995–1997). See figure 1 for description of sample selection (2711 adolescents had one or more siblings in the cohort, their mother being the common parent).

Figure 1.

Flow chart displaying how the study cohort was derived.

Ethics

Each student signed a written consent form to participate in the study, and parents or guardians of the students who were younger than 16 years old gave their written consent. The study was approved by the Regional Medicine Ethical Committee and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate.

Outcome measure—benefit receipt

The main outcome variable was medical benefit receipt from age 20 to 29. Medical benefits are defined as social insurance benefits received for more than 180 days during one calendar year and are intended to replace income lost because of health problems. These benefits included sickness absence, rehabilitation or vocational rehabilitation benefits and disability pension (http://www.nordsoc.org/). Additionally, medical benefit receipt was recorded each calendar year and according to age from 20 to 29 years (continuous registration starting at the beginning of 1998, ending registration in 2008 or in the case of death). An additional outcome variable was unemployment benefit receipt from age 20 to 29 (not including those who also received medical benefits), which included cases of unemployment if economic compensation was received for more than 180 days during one calendar year.

Anxiety and depression symptoms

Adolescent symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed with the five-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-5).18 In the SCL-5, the presence or absence of the following five symptoms during the last 14 days was reported: feeling blue, feeling fearful, feeling hopeless about the future, worrying too much about things and experiencing nervousness or shakiness inside. A four-point scale was used, ranging from 1 (‘not bothered’) to 4 (‘very much bothered’); we summed up the scale scores on each item and then divided the total sum by the number of items answered. The average SCL-5 scale score (range 1–4) was calculated for those who had answered at least three of the five questions. The adolescent symptom load was categorised as high or low according to established and recommended cut-off values of the SCL-5 scores.18 The high adolescent symptom load group included adolescents with SCL-5 scores of 2 or above, whereas the low adolescent symptom load group included adolescents with SCL-5 scores below 2. Parental symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which is a validated 14-item scale that consists of two 7-item scales covering anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D).19 Each item was scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, and was added up resulting in a score between 0 and 21 for each subscale. A high parental symptom load was defined as having a score of 8 or above (recommended cut-off value) on at least one of the subscales (HADS-A and/or HADS-D).19 Three groups were identified according to whether no parent, one parent or both parents had a high anxiety or depression symptom load.

Baseline covariates

Age was used as continuous variable, but also categorised as 12–14, 15–17 and 18–20 years. Somatic health was assessed by the self-reported presence of chronic disease (has a doctor ever diagnosed you with epilepsy, migraine, diabetes or asthma or have you had another disease lasting more than 3 months) and disability (medium or much impairment of hearing, movement or somatic illness or much impairment of vision). Variables were included in the analyses as dichotomous measures. Follow-up time was the number of years from 1998 to 2008 in which the participants were alive and aged 20–29, and thereby registered with benefit or no benefit. Parental educational attainment was measured for both parents by the level of completed education in 1995, categorised as primary education (compulsory school only), secondary education (completed high school) and tertiary education (university degree). Family risk factors were assessed by four dichotomous measures: teenage parent (families in which one or both parents were a teenager when the adolescent study participant was born), divorced (families with divorced parents), single parent (adolescent reporting living with only one parent) and living alone (adolescent reporting living alone).

Missing parental information and selection bias

The parental HADS scores were missing for 1669 fathers (22%) and 653 mothers (9%), while the educational level was missing for 630 fathers (8%) and 17 mothers (2%). We performed a multiple imputation of missing data in order to obtain complete datasets for the 7497 adolescents, including information on both parents. We conducted the procedure following recommendations in the current guidelines, 20 and using the chained equations option in the multiple imputation (mi) procedure in STATA statistical software to create 20 datasets. Extensive health measures from the HUNT surveys and information on demography and social insurance benefits for the adolescents, mothers and fathers were used as predictor variables (a total of more than 90 variables, details available upon request), so as to ensure the required assumption of ‘missing at random’.

Statistical methods

We used logistic regression analyses to explore the associations between anxiety and depression symptom exposures in adolescence and medical benefit receipt in young adulthood. Additional analyses were performed with unemployment benefits as an alternative outcome, and we explored the relationship between adolescent symptom load and benefit receipt by using both the continuous SCL-5 scale score and by a comparison of the groups according to symptom load (high vs low). For the continuous SCL-5 score we estimated the OR associated with a one point (+1) increase in the scale score (range 1–4). In the sibling subsample, we used a fixed-effect logistic regression model 21 to compare the anxiety and depression symptom level (the continuous SCL-5 score) within sibling groups to control for factors that are shared by siblings such as parental health, family socioeconomic status, home environment, etc.

We explored the relationship between adolescents’ family symptom load and benefit receipt by a comparison of the groups according to parental symptom load and according to combinations of adolescent and parental symptom load. Six groups were identified by combining the two adolescent symptom load groups (low and high) with the three parental symptom load groups (low, one parent high and both parents high). In the analysis, all five groups including high symptom loads were compared with the ‘low adolescent and low parental’ symptom load group (reference category).

All the analyses mentioned above were adjusted for sex, age and follow-up time. The results are presented as ‘Model 1’ in the text and tables. We adjusted for adolescent somatic health in a separate model, ‘Model 2’, regarding health as a potentially important confounder. ‘Model 3’ (not included in the fixed-effect model) included an additional adjustment for parental education and family risk factors. These family-related factors were regarded as potential confounders and/or intermediate factors. A potential effect measure modification by sex and age was explored by including interaction terms between SCL-5 scale scores and sex and SCL-5 scale scores and age in the analyses. The analyses were conducted using STATA 11 and STATA 12 software (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA). The results from logistic regression analyses were presented as OR, with the OR from the fixed-effect logistic regression (sibling comparison) having a cluster-specific interpretation.22 All the analyses were reported with 95% CI.

Results

Data were available for 3729 boys and 3768 girls, with a mean age of 16 years (SD=1.8) and a mean SCL-5 score of 1.45 (SD=0.48, range 1–4). The median follow-up time was 9 years (range 1–10), and medical benefits were received by 986 (13%) individuals and unemployment benefits by another 676 individuals (9%). Descriptive characteristics of the study cohort according to medical benefit receipt are presented in table 1 (table including unemployment benefits available as online supplementary table S3 in Appendix).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (1995–1997) of the adolescents and their parents in the study cohort according to medical benefit receipt age 20–29, the HUNT study, Norway

| No medical benefits (n=6511) |

Medical benefits (n=986) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |

| Adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms | ||||

| SCL-5 score, mean SD | 1.43 | 0.47 | 1.56 | 0.56 |

| High load* | 915 | 14 | 219 | 22 |

| Parental anxiety and depression symptoms*† | ||||

| Mother high load | 1218 | 20 | 229 | 26 |

| Father high load | 944 | 18 | 147 | 22 |

| Adolescent and parental symptom loads combined*† | ||||

| Adolescent low and parents low | 2751 | 59 | 293 | 50 |

| Adolescent low and one parent high | 1094 | 24 | 144 | 25 |

| Adolescent low and both parents high | 177 | 4 | 34 | 6 |

| Adolescent high and parents low | 378 | 8 | 76 | 13 |

| Adolescent high and one parent high | 196 | 4 | 30 | 5 |

| Adolescent high and both parents high | 51 | 1 | 10 | 2 |

| Girls | 3163 | 49 | 605 | 61 |

| Age 12–14 | 2218 | 34 | 306 | 31 |

| Age 15–17 | 3154 | 48 | 533 | 54 |

| Age 18–20 | 1139 | 17 | 147 | 15 |

| Chronic disease | 1375 | 21 | 311 | 32 |

| Disability | 368 | 6 | 122 | 12 |

| Sibling in cohort | 2375 | 36 | 336 | 34 |

| Mother tertiary education† | 1457 | 23 | 132 | 14 |

| Mother secondary education† | 4073 | 64 | 623 | 65 |

| Mother primary education† | 840 | 13 | 198 | 21 |

| Father tertiary education† | 1367 | 23 | 132 | 16 |

| Father secondary education† | 3793 | 63 | 524 | 63 |

| Father primary education† | 868 | 14 | 183 | 22 |

| Parents divorced | 1027 | 16 | 264 | 27 |

| Single parent | 533 | 8 | 113 | 11 |

| Teenage parents | 392 | 6 | 113 | 11 |

| Adolescent living alone | 364 | 6 | 73 | 7 |

*High anxiety and depression symptom loads defined by SCL-5 scale scores of 2 or above for adolescents and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores of 8 or above (on the anxiety or depression subscale) for parents.

†Variables with missing data, the number of missing observations indicated in parentheses; mother's anxiety and depression score (653), father's anxiety and depression score (1669), parental anxiety and depression (2263) mother's educational level (174) and father's educational level (630).

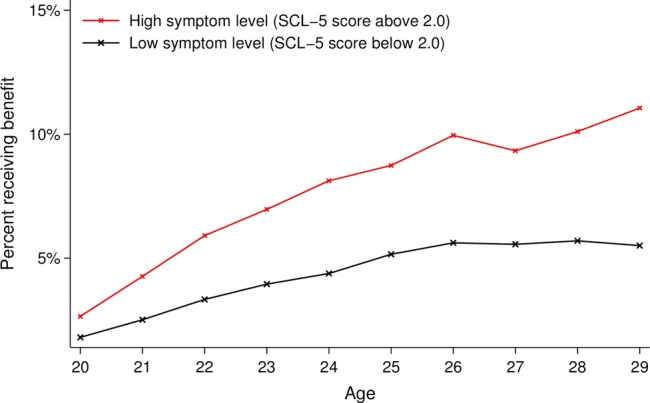

Adolescent symptoms of anxiety and depression

Figure 2 shows the percentage of adolescents who were in receipt of benefits at different ages during follow-up according to their SCL-5 score level. Symptoms of anxiety and depression among the adolescents were associated with higher odds of receiving medical benefits during follow-up (see table 2). The odds of receiving medical benefits increased by 50% following a one-point increase in the SCL-5 scale score. Adolescents in the high-symptom load group had about 60% higher odds of receiving medical benefits (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.87) compared with the low-symptom load group (analyses adjusted for sex, age and follow-up time). An adjustment for somatic health somewhat attenuated the estimates. There were no important differences in the estimates for boys and girls (p of interaction term between SCL-5 score and sex=0.58) and no statistically significant interaction term between SCL-5 score and age (p interaction=0.25). The OR of receiving unemployment benefits was 0.99 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.17) for a one-point increase in the SCL-5 scale score and 1.13 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.40) for adolescents in the high-symptom load group compared to the low-symptom load group (analyses adjusted for sex, age and follow-up time).

Figure 2.

Percentage of the Young-HUNT cohort (n=7497) in receipt of long-term medical benefits at different ages during follow-up according to self-reported anxiety and depression symptom level at baseline.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses associating family exposures of anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescence with receipt of medical benefits from age 20 to 29, imputed data

| Medical benefits from age 20 to 29 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1* |

Model 2* |

Model 3* |

||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms, n=7497 | ||||||

| SCL-5 scale score† | 1.47 | (1.29 to 1.68) | 1.33 | (1.17 to 1.53) | 1.29 | (1.12 to 1.48) |

| Low symptom load | 1.00 | (ref) | 1.00 | (ref) | 1.00 | (ref) |

| High symptom load | 1.58 | (1.33 to 1.87) | 1.42 | (1.20 to 1.69) | 1.37 | (1.15 to 1.64) |

| Adolescent and parental anxiety and depression symptoms, n=7497 | ||||||

| Adolescent low and parents low | 1.00 | (ref) | 1.00 | (ref) | 1.00 | (ref) |

| Adolescent low and one parent high | 1.31 | (1.08 to 1.58) | 1.29 | (1.06 to 1.56) | 1.16 | (0.96 to 1.41) |

| Adolescent low and both parents high | 1.92 | (1.38 to 2.69) | 1.88 | (1.34 to 2.64) | 1.56 | (1.10 to 2.22) |

| Adolescent high and parents low | 1.68 | (1.33 to 2.13) | 1.53 | (1.21 to 1.94) | 1.52 | (1.20 to 1.93) |

| Adolescent high and one parent high | 1.82 | (1.34 to 2.49) | 1.61 | (1.18 to 2.21) | 1.39 | (1.01 to 1.92) |

| Adolescent high and both parents high | 2.30 | (1.40 to 3.77) | 1.98 | (1.19 to 3.27) | 1.58 | (0.95 to 2.65) |

| Comparison of siblings within families, n=577‡ | ||||||

| SCL-5 scale score† | 1.86 | (1.25 to 2.76) | 1.65 | (1.10 to 2.48) | ||

*Model 1: adjusted for age, sex and follow-up time; Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, follow-up time and adolescent somatic health; Model 3: as Model 2, with additional adjustment for parental educational level and family risk factors.

†OR of a one point increase in the SCL-5 score (range1–4).

‡Fixed-effect model (conditional logistic regression).

Sibling comparison

When comparing siblings, the impact of anxiety and depression symptoms on the odds of medical benefit receipt was still pronounced, and the results are presented in the lower part of table 2. A one point increase in the SCL-5 score compared with the symptom level of their sibling(s) was associated with a 65% increase in the odds of medical benefit receipt when adjusting for sex, age, follow-up time and somatic health (Model 2). The impact of the SCL-5 score on the odds of unemployment benefit receipt yielded an OR of 1.11 (0.74–1.66) for a one point increase in the SCL-5 score in a model adjusted for age, sex and follow-up time (see online supplementary table S4 in appendix for details).

Family symptoms of anxiety and depression

Having parents with a high anxiety and depression symptom load was independently associated with medical benefit receipt from age 20 to 29. Compared with adolescents who had parents with low symptom loads, the OR of receiving medical benefits was 1.28 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.52) if one parent had a high symptom load and 1.85 (95% CI 1.38 to 2.47) if both parents had high symptom loads (analyses adjusted for sex, age and follow-up time). The corresponding OR of receiving unemployment benefits were 1.20 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.45) and 1.52 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.16). Adjustments for family characteristics (Model 3) attenuated all estimates, although the association between having two parents with a high symptom load and receiving medical benefits remained (OR 1.45 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.98)). In the upper part of table 2, we can see that the odds of medical benefit receipt were higher in all five groups with an increased symptom load, compared with the ‘low adolescent/low parental’ symptom load group. The OR attenuated following adjustment for adolescent somatic health (Model 2) and parental education and family risk factors (Model 3). The associations between different combinations of adolescent and parental symptom load and unemployment benefits in the offspring were weaker than for medical benefits, and were removed to a large extent after introducing family factors in Model 3 (results for unemployment are displayed in online supplementary table S4 in the appendix). Main results in the imputed data-set did not differ substantially from analyses on complete-case data (n=5186), but the strength of the associations between anxiety and depression symptom exposures and benefit receipt were somewhat stronger in the imputed data-set.

Discussion

In our study, anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescence were associated with an increased susceptibility to receive medical benefits in early adulthood, which was also true when we adjusted for confounding factors at the family level by comparing symptom loads within sibling groups. Parental anxiety and depression symptom load was an indicator of their adolescent's future risk of receiving medical benefits, and adolescents with both parents reporting high symptom loads seemed to be at a particularly high risk. Moreover, anxiety and depression symptoms were more strongly related to later receipt of medical than unemployment benefits.

Strengths and limitations

The originality and main contributions of our study are that it utilises a unique data material consisting of both parental and offspring health variables, as well as follow-up data from registers on later medical benefit receipt in the offspring. Assessments of anxiety and depression were performed using validated questionnaires,18 19 but the self-reported information used in our study was only from one occasion. Repeated measurements with structured diagnostic interviews may have provided more reliable information on anxiety and depression. However, such an approach is not feasible in a population study of this size. Because we did not have good data on psychiatric comorbidity in our study, we were unable to formulate a more detailed and differentiated picture of the risk following mental health vulnerability.

Missing parental data were a potential source of selection bias, and we performed a multiple imputation procedure in order to obtain complete parental data to help minimise this bias. The adolescents initially excluded from the study cohort (n=1012) because they had no participating parents were included in a sensitivity analysis of the relationship between SCL-5 score and benefit receipt (n=8509). The estimates obtained from these analyses were comparable to our reported findings, although somewhat lower. The consequences of mental disorders in adolescents and their parents on work integration are largely dependent on characteristics of the context such as the labour market and welfare regime. Our results should be interpreted with this in mind.

Results compared to existing literature

Our study's results are in accordance with studies from New Zealand,3–5 23 24 where symptoms of adolescent anxiety and depression and other mental illnesses have been associated with lower educational attainment, lower workforce participation and increased welfare dependence. Additionally, two large prospective Scandinavian population studies have described an association between mental impairment/psychiatric diagnosis among young men (at conscript, age 18 and 19) and risk of disability pension both early and later in adulthood.25 26 Other prospective studies relating anxiety and depression to unemployment, sick leave and disability pension primarily include cohorts of working adults who have already succeeded in entering the work force and may not grasp the particular challenges of young people in the transition to adulthood.6 7 An American prospective study of siblings and parents reported that childhood depression was strongly related to income as an adult, also when comparing siblings.27 This study represents one of the few that uses twin or sibling designs to study life outcomes following anxiety and depression in young people. Although there are many studies on the association between parental anxiety and depression and offspring mental health, the literature on the association between parental anxiety and depression and life outcomes in the offspring is scarce. Thus far, we have not found any studies that assess life outcomes for young people according to a combination of parental and adolescent anxiety and depression symptom load.

Interpretation of findings

One plausible mechanism may be that adolescents with high anxiety and depression symptoms have an increased risk of experiencing mental illness later in life,2–4 which may be the direct cause of work impairment. Also, anxiety and depression may impair adolescents’ ability to learn and thereby increase their risk of low educational attainment and school drop-out, which in turn are known to lower work participation and increase welfare dependence.28 The association between adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms and benefit receipt in young adulthood may also be influenced by factors that may increase both mental distress and the risk of receiving medical benefits such as the various somatic and psychiatric conditions that are associated anxiety and depression. We were able to adjust for somatic conditions in our study, but we did not have good data on psychiatric comorbidity. Other studies have shown that the number of psychiatric disorders a person has is related to life outcomes in young adulthood,5 and that co-occurring mental disorders, to a small extent, influenced the consequences of anxiety and depression.3 4 23 More general personal traits such as childhood temperament and intellectual abilities are other individual factors that may be of importance,26 29 but the effects of intellectual function and psychiatric disease seem independent of each other.25Our results indicated an influence of family factors, as indicated by the attenuation of OR in model 3. However, the association between adolescent symptom load and medical benefit receipt remained, even when all shared family factors were adjusted for in the sibling comparison.

Parental anxiety and depression symptom load were independently associated with medical benefit receipt in their offspring, which could be attributed to an increased vulnerability in the offspring related to increased mental health problems. Anxiety, depression and other mental illnesses are strongly associated in parents and offspring, both because of genetic and environmental influences.8 9 11 14 Parental anxiety and depression may have negative influence on the family, with consequences for offspring's cognitive, emotional and social development from an early age.10 12 Anxiety and depression in adults are associated with work exclusion,6 7 which could increase the strain on the children and adolescents in the family.30

Our finding that anxiety and depression symptoms were more strongly related to medical benefit receipt than to unemployment indicates that the work exclusion associated with anxiety and depression symptoms in the transition to young adulthood is primarily health related.

Implications and conclusions

Our study demonstrates that high levels of anxiety and depression symptoms among adolescents and their parents were associated with an increased risk of receiving medical benefits as the adolescents entered adulthood. Our findings suggest that assessing parental and adolescent symptom loads together could provide a more complete picture of the burden of anxiety and depression symptoms on adolescents as they enter into adulthood. Furthermore, adolescent and parental symptoms of anxiety and depression may be regarded as risk measures of previous, existent and future mental health vulnerability for the adolescents. This emphasises the importance of a family-oriented approach in mental health, not only in the assessment and treatment of anxiety and depression, but also in preventive public health strategies. Treatment and interventions for young people with symptoms of anxiety and depression should aim to stimulate education, increase work integration and obtain economic independence. Moreover, preventive measures should be taken to ensure better work-life integration for adolescents with anxiety and depression since young people with mental problems may be particularly vulnerable when facing today's labour market demands.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professors Steinar Westin and Roar Johnsen for their inspiration and useful comments on the manuscript, and Nils Kristian Skjærvold and Professor David Gunnell for their useful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: KP and JHB carried out the data processing, the epidemiological modelling and statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. TLH and SK participated in the design of the study and helped to write the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and by the Research Council of Norway. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (the HUNT Study) is a collaboration between the HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)), the Nord-Trøndelag County Council, the Central Norway Health Authority and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Each student signed a written consent form to participate in the study, and parents or guardians of students younger than 16 years old also gave their written consent. The study was approved by the Regional Medicine Ethical Committee and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the HUNT study (http://www.ntnu.no/hunt/english) and Statistics Norway.

References

- 1.Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, et al. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:764–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reef J, Diamantopoulou S, Van Meurs I, et al. Child to adult continuities of psychopathology: a 24-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;120:230–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:1086–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:225–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Burden of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood and life outcomes at age 30. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:122–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moncrieff J, Pomerleau J. Trends in sickness benefits in Great Britain and the contribution of mental disorders. J Public Health Med 2000;22:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mykletun A, Overland S, Dahl AA, et al. A population-based cohort study of the effect of common mental disorders on disability pension awards. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1412–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice F. The genetics of depression in childhood and adolescence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2009;11:167–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Lichtenstein P. A developmental twin study of symptoms of anxiety and depression: evidence for genetic innovation and attenuation. Psychol Med 2008;38:1567–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mensah FK, Kiernan KE. Parents’ mental health and children's cognitive and social development: families in England in the millennium cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:1023–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes EK, Gullone E. Internalizing symptoms and disorders in families of adolescents: a review of family systems literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:92–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewinsohn PM, Olino TM, Klein DN. Psychosocial impairment in offspring of depressed parents. Psychol Med 2005;35:1493–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amone-P'Olak K, Burger H, Ormel J, et al. Socioeconomic position and mental health problems in pre- and early-adolescents: the TRAILS study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009;44:231–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amone-P'Olak K, Burger H, Huisman M, et al. Parental psychopathology and socioeconomic position predict adolescent offspring's mental health independently and do not interact: the TRAILS study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn VJ, Abbott RA, Croudace TJ, et al. Profiles of family-focused adverse experiences through childhood and early adolescence: the ROOTS project a community investigation of adolescent mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donovan SJ, Susser E. Commentary: advent of sibling designs. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:345–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Krüger Ø, et al. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study 1995–97 (HUNT 2): objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiol 2003;13:19–32 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, et al. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry 2003;57:113–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic regression. a self-learning text. New York, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London: Springer, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. Texas, USA: Stata Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:335–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, et al. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gravseth HM, Bjerkedal T, Irgens LM, et al. Influence of physical, mental and intellectual development on disability in young Norwegian men. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:650–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson E, Leijon O, Falkstedt D, et al. Educational differences in disability pension among Swedish middle-aged men: role of factors in late adolescence and work characteristics in adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health Published Online First 7 November 2011. doi:10.1136/jech-2011-200317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JP, Smith GC. Long-term economic costs of psychological problems during childhood. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:110–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Ridder KA, Pape K, Johnsen R, et al. School dropout: a major public health challenge: a 10-year prospective study on medical and non-medical social insurance benefits in young adulthood, the Young-HUNT 1 Study (Norway). J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson M, Hotopf M, Leon DA. Childhood temperament and long-term sickness absence in adult life. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:220–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinhardt Pedersen C, Madsen M. Parents’ labour market participation as a predictor of children's health and wellbeing: a comparative study in five Nordic countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:861–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.