Abstract

Objectives

To quantify geographical concentration of falciparum malaria cases in the UK at a hospital level. To assess potential delay-to-treatment associated with hub-and-spoke distribution of artesunate in severe cases.

Design

Observational study using national and hospital data.

Setting and participants

3520 patients notified to the Malaria Reference Laboratory 2008–2010, 34 patients treated with intravenous artesunate from a tropical diseases centre 2002–2010.

Main outcome measures

Geographical location of falciparum cases notified in the UK. Diagnosis-to-treatment times for intravenous artesunate.

Results

Eight centres accounted for 43.9% of the UK's total cases; notifications from 107 centres accounted for 10.2% of cases; 51.5% of hospitals seeing malaria notified 5 or fewer cases in 3 years. Centres that saw <10 cases/year treat 26.3% of malaria cases; 6.1% of cases are treated in hospitals seeing <2 cases/year. Concentration of falciparum malaria was highest in Greater London (1925, 54.7%), South East (515, 14.6%), East of England (402, 11.4%) and North West (192, 5.4%). The North East and Northern Ireland each notified 5 or fewer cases per year. Median diagnosis-to-treatment time was 1 h (range 0.5–5) for patients receiving artesunate in the specialist centre; 7.5 h (range 4–26) for patients receiving it in referring hospitals via the hub-and-spoke system (p=0.02); 25 h (range 9–45) for patients receiving it on transfer to the regional centre from a referring hospital (p=0.002).

Conclusions

Most UK hospitals see few cases of falciparum malaria and geographical distances are significant. Over 25% of cases are seen in hospitals where malaria is rare, although 60% are seen in hospitals seeing over 50 cases over 3 years. A hub-and-spoke system minimises drug wastage and ensures availability in centres seeing most cases but is associated with treatment delays elsewhere. As with all observational studies, there are limitations, which are discussed.

Keywords: Infectious Diseases, Parasitology

Article summary.

Article focus

The concentration of imported malaria cases by hospital has implications for training, management and drug supply.

UK imported falciparum malaria is known to be concentrated at a regional level, but has not been analysed at a hospital or geographical level.

Artesunate, the drug of choice, is currently kept in regional centres and distributed by a hub-and-spoke arrangement when severe cases present.

Key messages

Most UK cases are seen in hospitals which see a lot of cases, but 25% of falciparum malaria is seen in centres which see less than a patient a month, and 6% in hospitals that see fewer than 2 cases a year.

A hub-and-spoke distribution system is associated with delay to starting treatment with artesunate for severe malaria.

When artesunate becomes freely available we should move towards universal distribution.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study uses national data from the Malaria Reference Laboratory (MRL) and data from probably the largest hub-and-spoke distribution system for intravenous artesunate in the UK.

The MRL operates a passive case detection system, so under-reporting is inevitable, though the capture rate is estimated to be at least 66%.

The number of cases provided artesunate from the hub-and-spoke distribution system is small: few patients were given intravenous artesunate in the period 2002–2010 and some records were incomplete.

Introduction

Falciparum malaria remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in returning travellers. In the UK, there are 1200–1600 cases of falciparum malaria annually, most from Africa or Asia, with an overall case-fatality rate of 7.4 per 1000 reported cases.1 Around 15% of falciparum cases in the UK are ‘severe’ (Malaria Reference Laboratory 2012) based on WHO criteria.2 Delay to effective treatment and lack of experience of dealing with severe malaria are associated with poor outcome in severe cases.3–5

Worldwide, parenteral quinine has been the mainstay of treatment for severe falciparum malaria for over a century and was first-line treatment in the last UK treatment guidelines (20076). However, two recent large multicentre randomised control trials have demonstrated a significant mortality reduction with intravenous artesunate versus intravenous quinine in severe falciparum infection in African children (AQUAMAT study7) and Asian adults (SEAQUAMAT study8). In light of this new evidence, WHO now recommends intravenous artesunate as first-line treatment for severe falciparum infections.2 It is almost certain the reduced mortality applies also in travellers returning from those regions. Artesunate is also easier to use than intravenous quinine: it can be administered as a bolus rather than an infusion; has no known cardiotoxicity; it is not known to cause hypoglycaemia associated with quinine.8 9 For these reasons, it is likely to replace quinine as the treatment of choice in the UK and other countries seeing cases of severe malaria once Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) licenced drug is available.

Intravenous artesunate is available in the UK but its use has been limited by restricted availability. Until recently, just one pharmaceutical company, based in Shanghai, was manufacturing the drug for international export. Their product, used in the AQUAMAT and SEAQUAMT trials,7 8 only gained WHO prequalification status in November 2010.10 Production is increasing worldwide but parenteral artesunate remains unlicensed for use in the UK. Few hospitals regularly stock intravenous artesunate and national supplies have been limited (June Minton, Hospital for Tropical Diseases, personal communication, 2012). Additionally the shelf-life of artesunate (around 18 months) is much lower than for quinine, an operational issue for hospitals which see few cases.

Given the clear outcome advantages of artesunate but its limited availability, two models of drug distribution might be considered: universal stock in all acute hospitals (blanket coverage) and a hub-and-spoke system where critical stocks are kept in specialist centres and couriered out when needed to hospitals with severe malaria cases. A form of hub-and-spoke system has operated to date.

Minimising delay to effective treatment is essential in severe cases.3 4 11 Geographical distance is a key consideration for delay. There is existing evidence of geographical clustering of malaria at a regional level,1 but this is too broad brush to help with decisions on a hub-and-spoke compared with blanket coverage distribution for a drug which many centres will use rarely if at all. In this study, we aim to quantify the geographical concentration of falciparum malaria in the UK at hospital level, using data from the Health Protection Agency Malaria Reference Laboratory. We also examine data from a tertiary tropical diseases centre that operates a hub-and-spoke system to distribute artesunate to referring hospitals, aiming to assess potential delay-to-treatment associated with this system. These data will inform decisions on the optimal means of distributing intravenous artesunate UK-wide. The geographical concentration of cases is also relevant to training needs for clinical and laboratory staff in the diagnosis and management of malaria. The approach should also help other countries with imported malaria which do not currently have universal artesunate coverage (most of them) consider the data they will need for their decisions.

Methods

Malaria is a notifiable disease in the UK: clinicians are required to report all cases by law. The Malaria Reference Laboratory (MRL), part of the UK Health Protection Agency (HPA), maintains the national surveillance database of reported malaria cases in the UK. It identifies malaria cases from statutory notification through local authorities; through laboratories sending blood films for diagnostic verification; through clinicians sending standardised malaria reports to the MRL. When a malaria case is notified, the MRL contacts the responsible clinician who is asked to complete a data collection form covering demographic and clinical data, including the notifying hospital's location and the patient's usual place of residence. This passive case detection system has been shown to identify at least 66% of cases of falciparum malaria in the UK12 and over 90% of cases in Scotland.13

The MRL database was used to identify the location of every notified case of falciparum malaria in the UK in the years 2008, 2009 and 2010. For Greater London, the notifying hospital's name was recorded given the large number of hospitals; outside Greater London, the notifying hospital's town was recorded. The patient's usual place of residence was also recorded. Cases were excluded if there was insufficient information to identify accurately the notifying hospital or town. Where the notifying hospital's location and the patient's usual place of residence differed significantly (eg, notified from Liverpool, place of residence Cardiff), the notifying hospital's location was recorded as case location.

Data were anonymised and analysis was performed using EpiInfo and STATA 11. For each notifying site, the annual frequency of falciparum malaria and the total number of cases over 3 years was calculated. Using the decimal geographic coordinates of each notifying site, maps showing the geographical distribution of falciparum malaria within the UK and within each UK region, weighted for caseload, were generated. Cases were also analysed by the UK Government Office Region from which they were reported (North East, North West, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England, South East, South West, Greater London, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales).14

The Hospital for Tropical Diseases (HTD), London has been using intravenous artesunate in cases of severe malaria since 2002 and provides a hub-and-spoke distribution service. It arranges for intravenous artesunate to be couriered from its permanent stocks to referring hospitals via its Tropical Medicine telephone advice service when requested based on clinical need. HTD's Pharmacy records were used to identify inpatients treated with intravenous artesunate at any hospital (including HTD) between 2002 and August 2010. The referring hospitals’ pharmacies were contacted and patient identities were confirmed. Patients’ medical and laboratory records were reviewed after seeking appropriate permission from the hospitals. A standardised proforma was used to record the following for every patient: demographics; parasitaemia; clinical features of severity (based on WHO criteria2); initial antimalarial used; time of malaria diagnosis; and time of first treatment with intravenous artesunate. All data were anonymised.

The diagnosis-to-treatment time was calculated for each case (time from the diagnosis of severe malaria as documented in the notes to time of first dose of intravenous artesunate as signed for on the drug chart). Differences between cases treated in a hospital with stocks, hospitals where artesunate was couriered and differences with hospitals which transferred patients were calculated by the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results

Geographical clustering of cases in the UK

Of 3556 cases of falciparum malaria notified to the MRL between 2008 and 2010: 1096 cases were in 2008; 1185 cases in 2009; 1275 cases in 2010. We excluded 12 cases from 2008 (9 Scotland, 1 Berkshire, 2 London); 11 cases from 2009 (9 Scotland, 2 London); 13 cases from 2010 (8 Scotland, 1 West Yorkshire, 2 London, 1 Surrey, 1 Somerset) due to incomplete geographical data, so in total 3520 cases are included in this study.

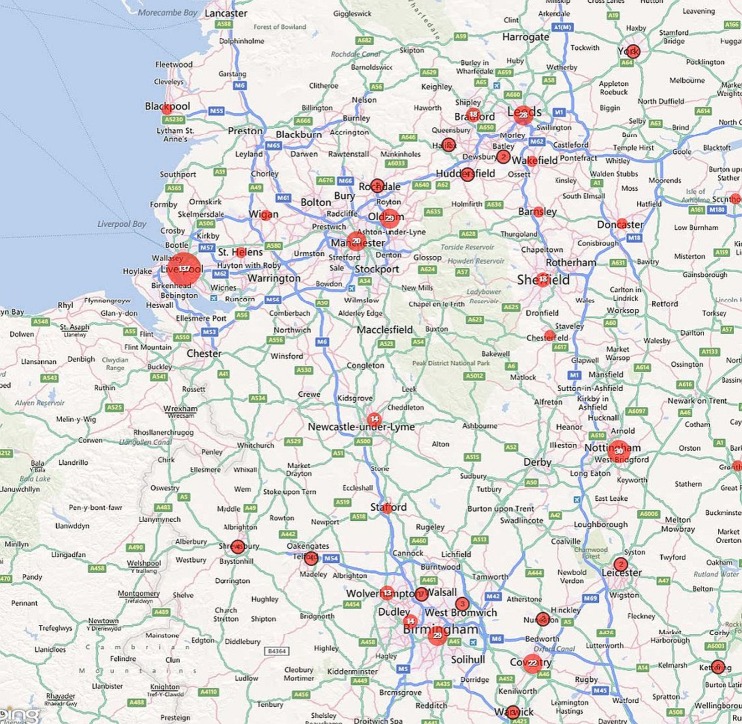

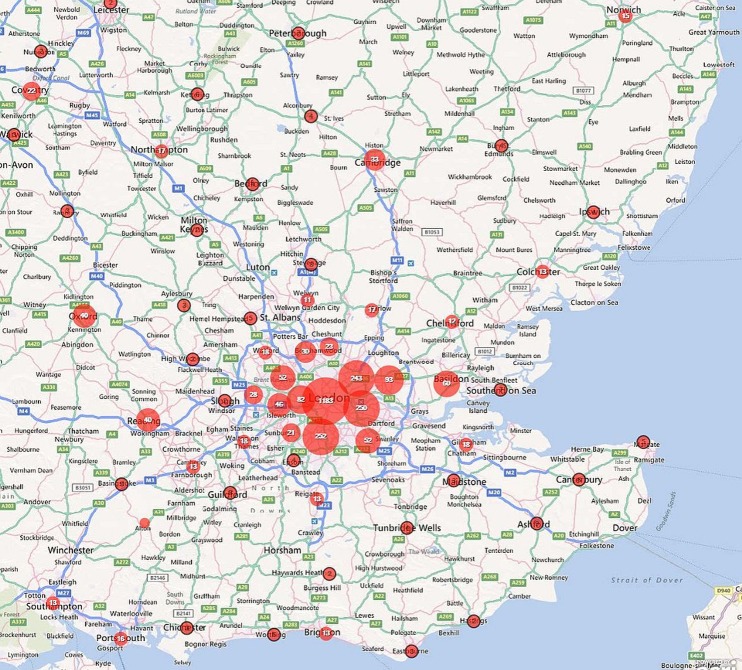

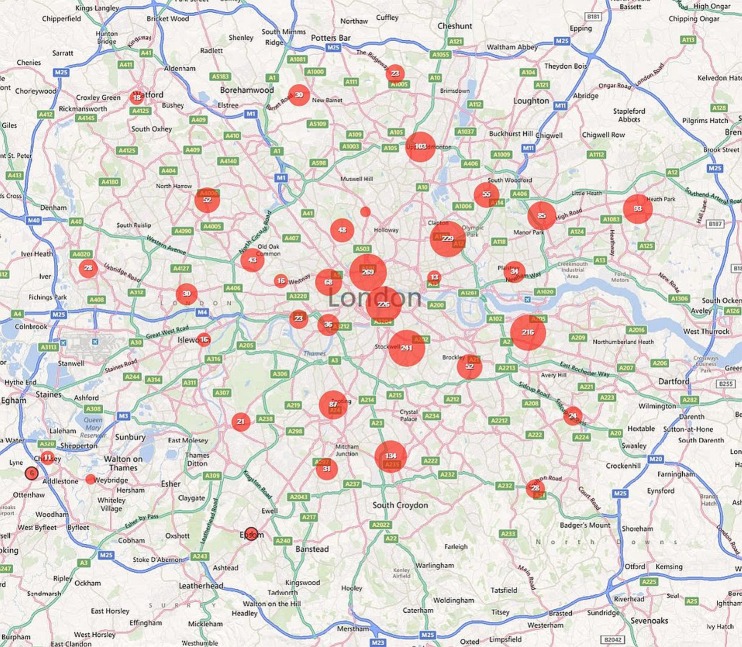

Of these cases, 54.7% were notified from London, 14.6% from the South East, 11.4% from Eastern England, 5.5% from the North West. Together, the North East of England and Northern Ireland accounted for just 0.6% of cases, each notifying five or fewer cases per year (table 1). Within all regions, cases were clustered around larger towns and cities and these are plotted out for the UK (Map 1), England (Map 2), the North West and West Midlands (Map 3), the South East and East of England (Map 4) and Greater London (Map 5).

Table 1.

Reported cases of falciparum malaria by UK region, 2008–2010

| 2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

All 3 years |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of total | Number | % of total | Number | % of total | Number | % of total | |

| North East | 1 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.4 | 10 | 0.3 |

| North West | 49 | 4.5 | 58 | 5 | 85 | 6.7 | 192 | 5.4 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 19 | 1.8 | 26 | 2.2 | 53 | 4.2 | 98 | 2.8 |

| East Midlands | 15 | 1.4 | 18 | 1.5 | 34 | 2.7 | 67 | 1.9 |

| West Midlands | 27 | 2.5 | 45 | 3.8 | 53 | 4.2 | 125 | 3.6 |

| East of England | 140 | 12.9 | 124 | 10.6 | 138 | 10.9 | 402 | 11.4 |

| South East | 164 | 15.1 | 161 | 13.7 | 190 | 15.1 | 515 | 14.6 |

| South West | 30 | 2.8 | 24 | 2.1 | 34 | 2.7 | 88 | 2.5 |

| Greater London | 614 | 56.6 | 682 | 58.1 | 629 | 49.9 | 1925 | 54.7 |

| Scotland | 13 | 1.2 | 18 | 1.5 | 22 | 1.7 | 53 | 1.5 |

| Wales | 10 | 0.9 | 10 | 0.9 | 16 | 1.3 | 36 | 1 |

| Northern Ireland | 2 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.3 |

| Total | 1084 | 1174 | 1262 | 3520 | ||||

Map 1.

Geographical distribution of falciparum malaria notifications in the UK, 2008-2010.

Map 2.

Geographical distribution of falciparum malaria notifications in England, 2008-2010.

Map 3.

Geographical distribution of falciparum malaria notifications in the North West and West Midlands, 2008-2010.

Map 4.

Geographical distribution of falciparum malaria notifications in the South East and East of England, 2008-2010.

Map 5.

Geographical distribution of falciparum malaria notifications in Greater London, 2008-2010.

Over the 3 years studied, eight centres notified more than 100 cases (6 Greater London hospitals, Croydon and Liverpool). Cases from these eight centres made up 43.9% of the UK's total cases. Notifications from 31 centres accounted for 73.7% of the UK's total; 18 of these were Greater London hospitals. In contrast, 140 centres that saw fewer than a case a month saw 26% of cases (924), and 6% of cases were seen in centres which saw less than two patients a year, many of which were some way from a potential hub (table 2 and maps).

Table 2.

Number of UK hospitals notifying cases of falciparum malaria, 2008–2010

| Number of cases notified in 3 years | Number of centres | Total number of cases | % of UK total cases | Cumulative % of UK cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >100 | 8 | 1547 | 43.9 | 43.9 |

| 51–100 | 8 | 552 | 15.7 | 59.6 |

| 26–50 | 15 | 497 | 14.1 | 73.7 |

| 11–25 | 33 | 565 | 16.1 | 89.8 |

| 6–10 | 19 | 143 | 4.1 | 93.9 |

| 1–5 | 88 | 216 | 6.1 | 100 |

Intravenous artesunate via hub-and-spoke and time-to treatment

HTD pharmacy records identified 50 patients who started intravenous artesunate, 22 at HTD. Clinical data were available for 21 of these HTD cases (one case missing medical records), 14 of whom were transferred in from referring hospitals. Records identified 28 patients in referring hospitals treated with intravenous artesunate sent from HTD. Of these 13 could be included in this study (8 cases had incomplete patient identifiers; 7 cases incomplete medical records). Ten patients were in London hospitals, two in the South East and one in Eastern England. Therefore, 34 patients were included in total: 21 men and 13 women, age range 17–70 years, median age 41 years. All were residents in the UK. Of these, 23 (68%) had returned from West Africa, 9 (26%) from East Africa, 1 from Central Africa (3%), 1 from Thailand (3%). High parasite count was the most common criterion for starting intravenous artesunate: 29 of the 34 had a count greater than 2% on admission; 24 had a count greater than 5%. On presentation, 12 had cerebral malaria (35%), 10 had respiratory distress (29%), 6 had acute renal impairment (18%) and 12 (35%) had 2 or more clinical features of severe malaria (table 3).

Table 3.

Falciparum cases treated with intravenous artesunate from the Hospital for Tropical Diseases (HTD)

| Age | Gender | County of residence | Country of travel | Parasitaemia on admission | Number of clinical features of severity | Admitting hospital | Site of first artesunate dose | Diagnosis-to-treatment time (h) | Initial antimalarial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | M | UK | Nigeria | 2.3 | 1 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 12 | IV quinine and doxycycline |

| 41 | M | UK | Gambia | 15 | 6 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 13 | IV quinine |

| 34 | F | UK | Nigeria | 37 | 1 | Elsewhere | HTD | 14 | IV quinine |

| 45 | M | UK | Gambia and Liberia | 27 | 0 | Elsewhere | HTD | 41.5 | IV quinine |

| 51 | M | UK | Nigeria | 15 | 3 | Elsewhere | HTD | 13 | IV quinine |

| 62 | F | UK | Ghana | 17 | 0 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 5 | IV quinine |

| 38 | M | UK | Nigeria | 8 | 1 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 26 | IV quinine and im artemether |

| 24 | F | UK | Uganda | 2.7 | 0 | HTD | HTD | 1 | IV artesunate |

| 24 | M | UK | Thailand | 2.6 | 0 | Elsewhere | HTD | 29 | IV quinine |

| 39 | M | UK | Kenya | 23 | 3 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 4.5 | IV quinine |

| 46 | M | UK | Nigeria | 8.1 | 2 | Elsewhere | HTD | 34 | IV quinine |

| 41 | M | UK | Uganda | 2.3 | 2 | Elsewhere | HTD | 9 | IV quinine |

| 47 | F | UK | Mozambique | 0.2 (recurrence) | 0 | HTD | HTD | 5 | IV artesunate |

| 46 | M | UK | Sudan | 20 | 2 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 8 | IV quinine |

| 45 | F | UK | Uganda | 1.8 | 1 | Elsewhere | HTD | 45 | IV quinine |

| 42 | M | UK | Nigeria | 1 | 0 | HTD | HTD | 3.5 | IV artesunate |

| 36 | M | UK | Nigeria | 0.3 | 1 | HTD | HTD | 1 | IV artesunate |

| 49 | M | UK | DR Congo | 15 | 1 | HTD | HTD | 5 | IV quinine |

| 17 | M | UK | Sierra Leone | 1.1 | 0 | HTD | HTD | 11 | IV quinine |

| 52 | F | UK | Ghana | 50 | 4 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | Unknown | IV quinine |

| 34 | F | UK | Ghana | 22 | 4 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 4 | IV artesunate and clindamycin |

| 52 | F | UK | Sierra Leone | 5.2 | 0 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | Unknown | Unknown |

| 27 | F | UK | Tanzania | 5 | 0 | Elsewhere | HTD | Unknown | IV quinine |

| 52 | M | UK | Kenya | 10 | 1 | Elsewhere | HTD | 33 | IV quinine |

| 36 | M | UK | Gabon | 17.2 | 0 | HTD | HTD | 0.5 | IV artesunate |

| 41 | F | UK | Ghana | 10 | 1 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 7.5 | IV quinine and doxycycline |

| 35 | F | UK | Ghana and Ivory Coast | 9 | 0 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | Unknown | IV quinine |

| 70 | M | UK | Nigeria | 8 | 1 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | Unknown | IV quinine |

| 51 | M | UK | Nigeria | 9.2 | 0 | Elsewhere | Elsewhere | 5 | IV quinine |

| 39 | M | UK | Uganda | 30 | 2 | Elsewhere | HTD | Unknown | IV quinine |

| 31 | F | UK | Nigeria | 4.8 | 1 | Elsewhere | HTD | Unknown | IV quinine |

| 30 | M | UK | Sierra Leone | 26.8 | 2 | Elsewhere | HTD | 21.5 | IV quinine |

| 47 | F | UK | Sierra Leone | 12.5 | 2 | Elsewhere | HTD | 14.5 | IV quinine |

| 43 | M | UK | Ghana | 16.4 | 3 | Elsewhere | HTD | Unknown | IV quinine |

F, female; IV, intravenous; M, male.

In 23 cases (68%) the diagnosis-to-treatment time could be calculated (data unavailable for the remaining 11 cases). For 4/4 patients admitted to HTD with severe malaria, median time was 1 h, range 0.5 to 5 h. For 9/13 patients who required artesunate to be couriered to their referring hospital, median time was 7.5 h, range 4–26 h, difference from the four treated in a hospital with drug stocks (HTD) of p 0.02 (rank sum). For 10/14 patients who presented elsewhere but were transferred to and given artesunate at HTD, median time was 25 h, range 9–45 h, difference from the patients where artesunate was couriered p=0.002. For 25/26 patients admitted to a referring hospital, intravenous quinine was given while they waited for intravenous artesunate. One patient did not receive any antimalarial on initial diagnosis of severe malaria and waited 4 h before receiving intravenous artesunate (table 3).

Current cost of drugs

By the standards of emergency life-saving drugs used in high-resource settings, artesunate is not expensive. Drug wastage associated with universal stockage poses an opportunity cost while artesunate supplies are limited, as hospitals seeing many cases may consequently have inadequate drug available.

There are however some cost implications, outlined for illustrative purposes (June Minton, personal communication, 2012). A course of 5×60 mg vials (total 300 mg) of artesunate at 2012 prices costs £287. A 60 kg adult would require 144 mg per dose, so would need 1.5 packs in the first 48 h including loading, costing £381. For intravenous quinine a pack of 10×300 mg amps (total 3000 mg) costs £41. A 60 kg adult would require 1200 mg loading dose, then 600 mg per dose thereafter. Assuming it is given twice daily, this would require 4200 mg in total for first 48 h, so about 1.5 packs, costing £61. Each adult treatment course of artesunate discarded after the expiry date would therefore be around £400 on current prices.

Discussion

This study shows that while the majority of UK patients with malaria are seen in centres which see many cases of malaria, a significant minority are seen in centres where malaria is rarely seen, and 216 cases (6.1%) were seen in centres which saw fewer than 2 cases a year. Since 5–15% of cases of falciparum malaria probably become severe (although data on this are not reliable)15 these centres will probably treat a severe case less than once every 5 years. There are 168 acute trusts in the UK and 171 centres reporting malaria over the 3 years, so it is seen occasionally in the majority of UK hospitals. A hub-and-spoke system for distributing artesunate was unsurprisingly associated with delays in starting treatment—in this study of a relatively limited number of patients of around 7 h.

The degree of clustering of malaria cases in hospitals has significant operational implications. These include whether rarely used but important drugs, especially parenteral artesunate, are distributed universally or by hub-and-spoke. It also has important implications for clinical care standards and training since malaria mortality is inversely related to experience at least at a regional level in the UK,5 a pattern which is almost certainly seen in other non-endemic countries. Identifying training needs and providing support for hospitals with less experience of malaria is important for minimising delays in diagnosis and improving clinical outcomes.

This hospital-level study is consistent with previous studies on the incidence of malaria in the UK regions1 5 and likely reflects the UK's demographics and travelling patterns. Outside London, the South East and East of England, the frequency of falciparum malaria was low. Together, the North East, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland accounted for less than 4% of all cases. The North East of England and Northern Ireland each notified approximately three cases of falciparum malaria per year. The MRL capture rate is 66% so we estimate these regions may each see 4 to 5 cases of falciparum malaria per year. Assuming 5–15% of falciparum cases become ‘severe’, we estimate each of these UK regions could expect to use intravenous artesunate once every 1 to 2 years. In Wales and Scotland we estimate that it might be used 3 to 4 times per year, with most hospitals using no drug but long geographical distances between hospitals.

UK intravenous artesunate supplies have been limited for several years for operational and regulatory reasons, and it is unlikely that this will be resolved soon. Until supplies improve, the UK and other non-endemic countries will need to distribute and use the drug efficiently and effectively. Intravenous artesunate has a shelf-life of around 18 months. Our data suggest that a universal stock system would lead to substantial drug wastage: more than 50% of the UK centres with at least one case notified 5 or fewer cases of falciparum malaria over 3 years and will seldom see severe cases; 2 UK regions notified less than 10 cases over 3 years. On the other hand, as our data show, a hub-and-spoke system will lead to delays in providing artesunate, and since this drug has been associated with over 20% reduction in mortality in adults such a delay is likely to be fatal in at least some cases.

Limitations

The MRL uses a passive case detection system, which relies on the clinician or laboratory to report malaria cases. Therefore under-reporting is inevitable; however, a capture–recapture study estimated that 66% of falciparum cases in England are detected by this system,12 which is high by international standards. Case-detection rate may vary by hospital or region as some units may disproportionately under-report cases. For example, the same study found that London had a higher detection rate than the rest of England. Hospitals that rarely see malaria may be less familiar with reporting systems; so this study may underestimate the proportion of the UK's malaria cases seen in these centres. Scotland has been shown to have a very high case-detection rate (over 90%13).

Of 34 cases excluded due to incomplete data on case location, 26 were from Scotland. These cases represent a significant proportion of the total number of Scottish cases; they would not have a significant impact on the overall trends described here but make extrapolating results to Scotland difficult. The Royal Liverpool Hospital and the HTD are national centres for Tropical Medicine, regularly receiving patients and malaria films from throughout the UK. In 98/127 Liverpool cases and 45/266 HTD cases included in this study, the notifier's location and the patient's usual place-of-residence were located in different counties or regions, including Greater Manchester, South West England, Scotland and Wales. It was not clear as to which of these cases represented referrals and which represented temporary visitors so all Liverpool notifications were coded as ‘Liverpool’ and all HTD notifications as ‘HTD’. Some of these patients may have presented elsewhere initially.

HTD operates probably the largest hub-and-spoke distribution system for intravenous artesunate in the UK. Despite this, the number of cases that could be included was small: 34/50 patients receiving intravenous artesunate during this time period could be included in this study. The data we have are retrospective. To calculate the diagnosis-to-treatment time, we used the times as documented in the medical records. Clinicians do not always document decisions or diagnoses immediately, so the diagnosis-to-treatment times may appear shorter in this study, which is therefore conservative on delay which may well in practice be longer than recorded.

Conclusions

If intravenous artesunate becomes first-line treatment for severe malaria in Europe, UK hospitals will require rapid and reliable access to this emergency drug. While artesunate supplies remain limited, a hub-and-spoke system, based around regional infection centres, will minimise drug wastage and ensure that the drug is available in the centres which see most cases, but will lead to delays, and almost certainly some avoidable deaths in centres which less regularly see cases and are geographically some way from hubs. A system which restricts artesunate to hospitals that see over 100 cases in 3 years would lead to two-thirds of cases being in other centres. Even having artesunate in the 31 hospitals that see more than 50 cases in 3 years would leave over 25% of malaria cases being treated elsewhere. When parenteral artesunate becomes more freely available, these data suggest that the UK should move rapidly towards universal drug distribution, aiming for all acute hospitals to maintain permanent stocks, to ensure early artesunate treatment for all UK severe malaria cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding for the Malaria Reference Laboratory from the Health Protection Agency, and additional support from the Special Trustees of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. Funders had no part in design, analysis or decision to publish. PLC and CJMW are part of the Malaria Centre, LSHTM. PLC is supported by the UCL Hospitals Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre Infection Theme.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed by CB, CW and PG. Data collection on drugs was by CB, and on geographic data by VS and MB. Geographic data were analysed by PF. Other data were analysed by CB and CW. The paper was drafted by CB. All authors contributed to the final draft. CB is the guarantor.

Funding: The MRL is supported by the UK Health Protection Agency.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the Malaria Reference Laboratory are available on request for specific research studies. Aggregate data are published annually at http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/Malaria/.

References

- 1.Smith A, Bradley D, Smith V, et al. Imported malaria and high risk groups: observational study using UK surveillance data 1987–2006. BMJ 2008;337:a120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd edn. Geneva: The World Health Organization, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman RD, Parise ME, Barber AM, et al. Malaria-related deaths among U.S. travelers, 1963–2001. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:547–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christen D, Steffen R, Schlagenhauf P. Deaths caused by malaria in Switzerland 1988–2002. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;75:1188–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Checkley A, Smith A, Smith V, et al. Risk factors for mortality from imported falciparum malaria in the United Kingdom over 20 years: an observational study. BMJ 2012;344:e2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lalloo DG, Shingadia D, Pasvol G, et al. UK malaria treatment guidelines. J Infect 2007;54:111–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dondorp A, Fanello C, Hendriksen I, et al. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1647–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, et al. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomised trial. Lancet 2005;366:717–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton PN, Angus BJ, Chierakul W, et al. Randomised comparison of artesunate and quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Prequalification programme: a United Nations programme managed by WHO, 2010. http://apps.who.int/prequal/ (accessed 1 Dec 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomes MF, Faiz MA, Gyapong JO, et al. Pre-referral rectal artesunate to prevent death and disability in severe malaria: a placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:557–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cathcart SJ, Lawrence J, Grant A, et al. Estimating unreported malaria cases in England: a capture-recapture study. Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:1052–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unger HW, McCallum AD, Ukachukwu V, et al. Imported malaria in Scotland—an overview of surveillance, reporting and trends. Travel Med Infect Dis 2011;9:289–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for National Statistics http:// www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/geography/beginner-s-guide/administrative/england/government-office-regions/index.html (1 Jan 2012).

- 15.Lubell Y, Staedke SG, Greenwood BM, et al. Likely health outcomes for untreated acute febrile illness in the tropics in decision and economic models: a Delphi survey. PLoS One 2011;6:e17439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.