Abstract

Objectives

Compared with controls, multiple sclerosis (MS) patients die, on average, 7–14 years prematurely. Previously, we reported that, 21 years after their participation in the pivotal randomised, controlled trial (RCT) of interferon β-1b, mortality was reduced by 46–47% in the two groups who received active therapy during the RCT. To determine whether the excessive deaths observed in placebo-treated patients was due to MS-related causes, we analysed the causes-of-death (CODs) in these three, randomised, patient cohorts.

Design

Long-term follow-up (LTF) of the pivotal RCT of interferon β-1b.

Setting

Eleven North American MS-centres participated.

Participants

In the original RCT, 372 patients participated, of whom 366 (98.4%) were identified after a median of 21.1 years from RCT enrolment.

Interventions

Using multiple information sources, we attempted to establish COD and its relationship to MS in deceased patients.

Primary outcome

An independent adjudication committee, masked to treatment assignment and using prespecified criteria, determined the likely CODs and their MS relationships.

Results

Among the 366 MS patients included in this LTF study, 81 deaths were recorded. Mean age-at-death was 51.7 (±8.7) years. COD, MS relationship, or both were determined for 88% of deaths (71/81). Patients were assigned to one of nine COD categories: cardiovascular disease/stroke; cancer; pulmonary infections; sepsis; accidents; suicide; death due to MS; other known CODs; and unknown COD. Of the 69 patients for whom information on the relationship of death to MS was available, 78.3% (54/69) were adjudicated to be MS related. Patients randomised to receive placebo during the RCT (compared with patients receiving active treatment) experienced an excessive number of MS-related deaths.

Conclusions

In this long-term, randomised, cohort study, MS patients receiving placebo during the RCT experienced greater all-cause mortality compared to those on active treatment. The excessive mortality in the original placebo group was largely from MS-related causes, especially, MS-related pulmonary infections.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Health Economics

Article summary.

Article focus

Twenty-one years after the randomised controlled trial (RCT) of interferon β-1 b (IFNβ-1b), mortality was reduced by 46–47% in those patients who were randomised to receive active treatment during the trial.

The hypothesis tested in this study was that the excessive number of deaths found in the placebo-treated cohort would be due to multiple sclerosis (MS)-related causes.

Key messages

The excessive number of deaths found in placebo-treated patients was due to MS-related causes.

These data support the notion that the mortality benefit from IFNβ-1b is due to a treatment-related impact on the MS disease process itself.

The nearly identical findings in the two independently randomised groups provide strong supportive evidence that the observed survival benefit is not due to chance.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study had almost complete ascertainment (98.4%) after 21 years from the time of RCT enrolment.

This study cannot resolve the question of whether the impact of therapy on mortality is the consequence of early treatment or a larger cumulative exposure to IFNβ-1b.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, which has been consistently associated with a significant increase in the risk of death compared with an age-matched and sex-matched control population.1–8 To estimate this increased mortality risk, one metric commonly used in survival studies is the so-called standardised mortality ratio (SMR). This measure assesses the ratio of the mortality in patients with a condition (over the entire period of observation) divided by the mortality in an age-matched and sex-matched cohort (over the same interval) without the condition.9 10 In MS, the SMR is generally in the range of 2–3, indicating that, in MS patients, death is 2–3 times more likely over the observation period than in age-matched and gender-matched controls.1 2 9–13 An alternative metric of effect on longevity in MS patients is the average time from clinical onset to death. This time is approximately 35 years (ranging from a low of 24.5 years in a Scottish cohort to a high of 45 years in a New Zealand cohort). Thus, compared with unaffected age-matched and sex-matched controls, MS patients die, on average, 7–14 years prematurely.1 2 12 14 15

Importantly, long-term outcomes such as the avoidance of unambiguous physical impairment, the ability to remain employed, and survival are of far greater importance to patients and families than are the short-term clinical and MRI outcomes measured during randomised controlled trials (RCTs). For this reason, long-term follow-up (LTF) studies are essential to assess the true impact of MS therapies on the disease. Nevertheless, such studies are difficult to execute successfully. The study of mortality in MS has been infrequent and, even then, only as part of natural history studies.1 11 12 Moreover, and particularly in the past 20 years, the potential impact of therapy on mortality has been largely ignored.

Recently, we reported our experience at 21 years (the 21Y-LTF) in the cohort of relapsing-remitting (RR) MS patients who had previously participated in the pivotal RCT of interferon beta (IFNβ)-1b for MS.16–19 After a median of 21.1 years from RCT enrolment, we identified 98.4% (366/372) of the original patient cohort. In this group, 81 deaths were recorded (22.1%; 81/366). Patients originally randomised to receive IFNβ-1b (either 250 or 50 µg; every other day subcutaneously) had a significant reduction in the hazard rate for ‘all-cause’ mortality (46.8% and 46.0%, respectively) over the 21-year period compared with patients originally randomised to receive placebo.

Although these findings clearly imply a mortality benefit of therapy, it is, nevertheless, important to determine both the causes of the observed deaths in these cohorts and the relationship between these deaths and the underlying MS. Thus, it is only through such an undertaking that one can connect the mortality benefit to an impact of therapy on MS. Nevertheless, this task can be problematic because the recorded cause-of-death (COD) may be unreliable due to multiple factors. These include the infrequency of autopsies in MS patients, the recording physician's lack of knowledge of the patient's medical history, and the absence of uniform diagnostic criteria.4 13 Similarly, establishing the MS relationship is often difficult because MS may be only an indirect contributor to death. For example, MS-related disability (either physical or cognitive) can predispose patients to a variety of other illnesses or conditions that, by themselves, can be fatal (eg, aspiration pneumonia, sepsis from pressure sores or urinary tract infections, deep-vein thromboses with subsequent pulmonary emboli, suicide, etc).

In the present study we aimed to develop a reliable method to determine the COD for the patients who died and to assess the relationship of these deaths to MS. We also aimed to establish whether the excessive 21-year mortality, which was observed in patients originally randomised to placebo, was due either to MS related or non-MS-related causes.

Methods

Patients

All patients enrolled in the pivotal RCT of IFNβ-1b in RRMS were eligible to participate in the 21Y-LTF. The inclusion criteria, design and methods for the original RCT have been published.16 Briefly, treatment-naive RRMS patients (aged 18–50 years) with an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score ≤5.520 and with two or more clinical exacerbations within the prior 2 years, were randomised to receive IFNβ-1b 50 µg (n=125), IFNβ-1b 250 µg (n=124), or placebo (n=123) every other day. During the RCT, patients were treated and prospectively followed for a period of up to 5.1 years on their assigned treatment regimen (mean: 3.3±1.4 years; median: 3.8 years; range: 0.1–5.1 years). At the end of the RCT in 1993, subsequent use of disease-modifying treatment (DMT) was at the discretion of patients and their physicians. IFNβ-1b was the only DMT available until 1996 when the use of alternative DMTs became possible.21 Post-RCT treatment information was available for 67% (249/372) of the original RCT population at the time of the 16-year (16Y)-LTF study.21 Of these, 55% (138/249) received only IFNβ-1b and, in the remainder, there were no systematic differences in treatment or care observed across the three RCT-defined cohorts.21 Treatment information for the final 5 years of follow-up was largely unavailable.

Study design and determination of vital status

Between 1 October 2009 and 15 December 2010 (approximately 21 years after RCT enrolment), investigators at each study site attempted to identify each of the 372 randomised patients who took part in the IFNβ-1b RCT.16 17 19 They also attempted to determine the vital status for each of their study participants and to collect COD information for those who had died during the 21-year follow-up period. For patients whose vital status could not be determined by the investigators, further searches, using both public domain and private sources, were undertaken. For US sites, these included both death certificates, the US National Death Index (NDI), medical records, ‘notes to file’ by investigators, data from the RCT and the 16Y-LTF,16 17 19 21 22 and (when possible) the ‘in-person’ information from relatives. For Canadian sites, the same data sources were utilised except for the NDI, which was not available.

The treatment cohorts at the time of the original randomised treatment assignment were maintained for the entire 21-year period of follow-up and a strict intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was undertaken. The different treatment-allocation cohorts (from the RCT) were well balanced for all baseline demographic variables.16 17 19 This study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Appropriate written informed consent was obtained. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site.

Establishing cause of death

An adjudication committee, established to assess both the underlying COD and the relationship of death to MS in each of patients who died during the 21Y-LTF, consisted of five members, three of whom voted. The voting members included two neurologists (SC and GE) and a critical care specialist (TO). Two of these three members (SC and TO) did not participate in the 21Y-LTF (ie, they were completely independent). In addition, two non-voting members also served on the committee—a neurologist representative from Bayer (VK)—who oversaw the deliberations—and an academic biostatistician (GC). Committee members were blinded to the treatment allocation of the deceased patients. All COD categorisations and MS relationships required unanimous agreement of the voting members.

Predefined rules were used to classify the underlying COD and each case was assigned to one of the following nine COD categories:

Cardiovascular disease and stroke

All cancers

Pulmonary infectious diseases

Sepsis

Accidental death

Suicide

Death due to MS

Other known causes

Unknown or indeterminate cause

The relationship of death to MS was determined using a predefined decision algorithm (table 1) using a variety of information sources. Three possible relationships of CODs to MS were considered: (1) CODs always related to MS; (2) CODs probably related to MS and (3) CODs probably not related to MS.

Table 1.

Decision algorithm for determining the relationship of death to MS

| Always MS related | Probably MS related | Probably not MS related |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Suicide | 1. Brainstem dysfunction | 1. CV disease and stroke |

| 2. EDSS ≥7.0 prior to death | 2. Pulmonary infections | 2. All cancers |

| 3. MS the only listed COD | 3. Aspiration pneumonia | 3. Other infections |

| 4. Death due to MS | 4. Respiratory insufficiency | 4. Single organ failure |

| 5. Death from MS treatment | 5. Pulmonary embolism | |

| 6. Sepsis (especially uro-sepsis) | ||

| 7. Death due to trauma |

COD, cause-of-death; CV, cardiovascular; EDSS, Extended Disability Status Scale; MS, multiple sclerosis.

For the first of these possible MS relationships, it was agreed a priori that all suicides would be considered MS related. This rule was invoked in eight patients (evenly divided among the treatment arms). Also, if MS was listed as the first (or only) COD on the death certificate, then the death was classified as ‘death due to MS’, which was, by definition, MS related. This rule was applied to 21 patients. Finally, if the patient had reached an EDSS ≥7 at any time prior to their demise, the death was always considered to be MS related, regardless of the recorded COD. This rule was invoked to determine the MS relationship in six patients. In three of these, the COD was indeterminate but advanced disability was known to be present. In only three instances was this rule applied to patients in whom a COD other than MS was recorded—in two with a suspected cardiovascular COD and in one with a multisystem organ failure. These three patients were evenly divided among the treatment arms and excluding did not alter the analysis.

For the second of these possible MS relationships, it was agreed a priori that deaths due to brainstem dysfunction, aspiration pneumonia, respiratory insufficiency, sepsis, pulmonary embolism, trauma or side effects of treatment were likely to be MS related. In these cases, however, determination of the MS relationship was judged by the context in which the death occurred and required some ancillary information. For example, death from a pulmonary embolism would be considered MS related if the patient were known have had marked lower-extremity weakness and/or was confined to wheelchair or bed and, especially, if the embolus was from a deep-vein thrombosis thought secondary to the patient's immobility. In contrast, the embolus would not be considered to be MS related if it occurred spontaneously in a fully ambulatory individual.

For the third of these possible MS relationships, it was agreed a priori that deaths due to cancer, cardiovascular disease, infections (other than pulmonary or urinary tract) and single organ failures were unlikely to be related to MS unless they were either judged to be complications of treatment or the patient had an EDSS ≥7 prior to death. In this study, two deaths from cardiovascular disease and one death from bladder cancer (believed secondary to treatment with cyclophosphamide) were judged to be MS related (based on the EDSS or other criteria of our decision algorithm—see table 1).

Statistical analyses

Only descriptive statistics were undertaken. Frequency tables were created to display our results and the means and SDs were computed for several of our parameter-estimates.

Results

Disposition of patients

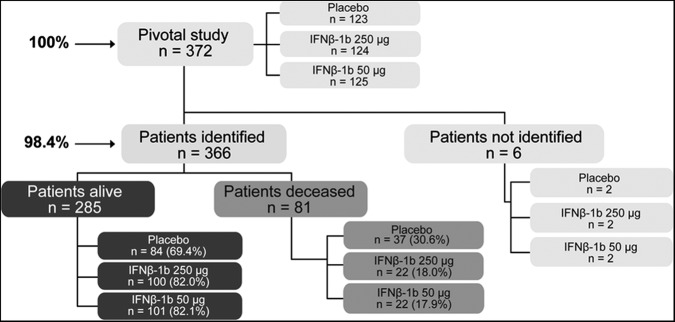

Of the 372 patients originally enrolled in the RCT, 366 (98.4%) were identified in the 21Y-LTF (figure 1). Of the six patients lost to follow-up, two were in each of the three randomised treatment groups (figure 1). These patients were in the study for periods of less than the length of the original trial and three of six withdrew from the RCT within 3 months of its start. Survival in these patients was very unlikely to have been influenced by their treatment assignment. The remaining three patients terminated their participation in the RCT after 1.2, 2.9 and 4.2 years.

Figure 1.

Trial conduct procedure.

In the cohort of 366 identified patients, 81 (22.1%) were dead after a median interval of 21.1 years from RCT enrolment (figure 1). Among these, the average age at death (±SD) was 51.7 (±8.7) years. The COD could be assigned in 82.7% (67/81) and in all but two of these patients (65/81), the relationship between death and MS could be established (table 2). The MS relationship to death could be determined in four additional patients (table 1) despite the inability to assign a COD (table 2). Thus, the relationship between death and MS could be established in 85.2% (69/81) of the deaths (tables 2 and 3), and the COD, the MS relationship, or both could be determined in 88% (71/81) of the deaths.

Table 2.

Number of patients in each COD category and the MS relationship for the 81 deaths in the different randomised treatment-allocation groups (numbers in parentheses represent MS-related deaths)

| IFNβ-1b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 50 µg | 250 µg | Total | |

| Number of Deaths | 37 | 22 | 22 | 81 |

| Category of death | ||||

| 1. Cardiovascular disease and stroke | 4 (1) | 1 (0) | 5 (1) | 10 (2) |

| 2. All cancers | 1 (0) | 3 (0) | 2 (1) | 6 (1) |

| 3. Pulmonary infectious diseases | 12 (11) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 17 (16) |

| 4. Sepsis* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Accidental death | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| 6. Suicide | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 8 (8) |

| 7. Death due to MS | 9 (9) | 6 (6) | 6 (6) | 21 (21) |

| 8. Other known COD | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Total: COD known | 32 (25) | 15 (11) | 20 (15) | 67 (51) |

| Other MS relationships | ||||

| COD known; MS relation unknown | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| MS relation known; COD unknown | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| COD unknown; MS relation unknown | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| Total: MS relationship known | 32 | 17 | 20 | 69 |

*NB: The NDI death-certificate data does not include ‘sepsis’ as a separate COD category. Therefore these entries are all zero.

COD, cause-of-death; IFNβ-1b, interferon β-1b; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Table 3.

Adjudicated MS relationship for the 81 observed deaths in the different randomised treatment-allocation groups.

| IFNβ-1b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 50 µg | 250 µg | Total | |

| Total number of deaths* | 37 (45.7%) | 22 (27.2%) | 22 (27.2%) | 81 (100%) |

| MS relationship indeterminate | 5 (6.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | 2 (2.5%) | 12 (14.8%) |

| Total MS relationship known† | 32 (46.4%) | 17 (24.6%) | 20 (29.0%) | 69 (100%) |

| MS related | 26 (37.7%) | 12 (17.4%) | 16 (23.2%) | 54 (78.3%) |

| Not MS related | 6 (8.7%) | 5 (7.2%) | 4 (5.8%) | 15 (21.7%) |

| Expected in null condition‡ | 33 (33.3%) | 33 (33.3%) | 33 (33.3%) | 69 (100%) |

| MS related | 18 (26.1%) | 18 (26.1%) | 18 (26.1%) | 54 (78.3%) |

| Not MS related | 5 (7.2%) | 5 (7.2%) | 5 (7.2%) | 15 (21.7%) |

*Numbers represent the number of patients in each category. Numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of the total deaths (81) in each category for each treatment group separately. Total represents the combined numbers for all treatment arms.

†Numbers represent the number of patients in each category. Numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of the total deaths where MS relationship known (69) in each category for each treatment group separately. Total represents the combined numbers for all treatment arms.

‡The null condition represents the number of deaths expected in each of the three treatment groups if the 69 observed deaths (54 MS related; 15 not MS related) had been distributed evenly between groups. In the circumstances of the present study, there were nine more deaths than expected in the placebo-treated group (eight MS related and one not MS related) and, similarly, nine fewer deaths than expected in the two treated groups combined.

IFNβ-1b, interferon β-1b; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Cause of death

CODs for the deceased patients are shown in table 2 and, of the 67 patients in whom a COD could be assigned, ‘death due to MS’ was the principal underlying COD in 31.3% (21/67). Two patients were assigned to the category of death due to ‘other known causes’—one placebo-patient from a GI bleed and one patient in the IFNβ-1b 50 µg group who died from multisystem organ failure. The MS relationship to the death was determined in both patients—the adjudication committee judged the multisystem organ failure to be, and the GI bleed not to be, MS related (table 2). In one patient in the IFNβ-1b 250 µg group the MS relationship could not be determined despite the death being in the COD category of ‘cardiovascular disease and stroke’. Following application of the decision algorithm for MS relatedness (table 1), 54 of the deaths were adjudicated to be MS related (tables 2 and 3). This represents 78.3% (54/69) of the adjudicated deaths and 67% (54/81) of the total observed deaths in the 21Y-LTF.

Almost all of the excess in deaths observed in patients originally assigned to the placebo group were adjudicated to be MS related (table 3). Indeed, the percentage of deaths due to MS in each of the two treatment arms was about half that observed in the placebo group (table 3). Moreover, these deaths were accounted for, almost entirely, by an excess in the number of fatal pulmonary infections (table 2). By contrast, non-MS-related deaths are evenly distributed among the different treatment-groups (table 3).

Discussion

This study provides considerable insight into the relationships between the early mortality in an MS cohort, the accrual of MS-related disability, and the impact of therapy on outcome in RRMS patients. In our earlier 21Y-LTF report,18 we observed that the HR for death was significantly reduced by 46.8% in the IFNβ-1b 250 µg group and by 46.0% in the IFNβ-1b 50 µg group compared to placebo. This nearly identical effect size in the two independently randomised groups provided strong supportive evidence that the observed survival benefit was not due to chance (ie, from a type I error). Although it was still possible that the observed benefit reflected an unusually high death rate in the placebo arm, this too seemed unlikely given the virtual overlap of placebo-group mortality with natural history studies18 (ref. 14, supplementary figure e-1) Thus, the survival rate for 29 years after disease onset (∼70%) observed by others2 was much like that in our placebo group (70.4%). In addition, the fact that after completion of the RCT, some patients chose to receive alternative therapies,21 does not detract from the findings. The 21Y-LTF analysis was done on a strict intent-to-treat basis. Moreover, the use of alternative therapies after randomisation will make any differences between the cohorts less (not more) conspicuous and, thus, should favour the null-hypothesis. Therefore, taken together, these findings of the 21Y-LTF strongly support the notion that there is a survival advantage following either earlier (or greater) exposure to IFNβ-1b.18

The patient population included in this cohort study is relatively young in the context of mortality and, indeed, our cohort exhibits many of the expected trends from such a circumstance. Thus, the average age (±SD) at the time of the 21Y-LTF was 56.3 (±7.1) years, with an average age at death even younger (51.7±8.7 years)—a feature characteristic of young and active cohorts.2 3 11 Also typical of younger MS populations, the observed suicide rate was quite high (11.9%; 8/67). Moreover, the large majority of the deaths observed over the course of 21 years were due to MS-related causes. This finding is anticipated in a younger cohort, where diseases of the elderly (eg, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer) are yet to overtake MS as the principal COD.1 13 23 Thus, in the 21Y-LTF, ‘death due to MS’ accounted for 31.3% (21/67) of the assignable CODs and ‘MS-related death’ accounted for 78.3% (54/69) of the assignable relationships and 67% of all deaths; these were more frequent compared with the combined category of cardiovascular disease, stroke and cancer, which accounted for only 23.9% (16/67) of the assignable CODs (tables 2 and 3). In reports on more complete survival-cohorts,1 13 23 MS-related mortality ranges between 50% and 65%.

In addition to the fact that most of the observed deaths in this cohort were MS related, three other observations support the notion that the observed intergroup differences in death are likely due to the MS disease state. First, the excess in ‘all-cause’ mortality in the placebo-assigned group is due, almost entirely, to an excess in MS-related deaths and not to other CODs (table 3). Second, the excess in MS-related deaths is largely attributable to an excess in fatal pulmonary infections, a complication known to occur in end-stage MS (table 2). And, third, both of these observations were highly consistent in the two groups of patients who received active treatment during the RCT compared to those who received placebo (table 3). Taken together, these observations support the notion that the mortality benefit provided by IFNβ-1b therapy is related to a reduction in MS-related disability and, secondarily, from those complications, which are known to occur in the setting of advanced MS.

These findings underscore the importance of conducting LTF studies after completion of the RCTs that lead to product approval, particularly when they use (as ours did) a strict ITT analysis, have very high ascertainment rates, and measure unambiguously objective endpoints. Although, there has been some surprising controversy about the need to perform group-matching procedures in these randomised LTF populations, several methodologists have pointed out that such procedures (in randomised trials) can actually introduce bias where none existed earlier.24–27

A very important feature of our study is its near-complete ascertainment rate for survival data of the cohort (98.4%). This stands in stark contrast to previous LTF studies of MS patients,28–30 in which ascertainment rates were substantially less (39.8–68.2%). Low ascertainment rates substantially increase the likelihood of bias, because patients who are lost to follow-up are more likely to be deceased than those who are actually located.31 In addition, the rules used for classifying the different CODs and establishing their MS relationship in this study were predefined and each assignment required the unanimous agreement of the three voting members on the adjudication committee (two of whom were completely independent of the 21Y-LTF). The fact that the observed COD in our cohort was usually MS related is, in general, consistent with previous reports;1–4 however, the actual percentage of MS-related deaths (78.3%, 54/69) was somewhat higher than the 50–70% reported by others.2–4 13 32 33 The reason for this is uncertain but probably reflects the younger age, the relatively early analysis compared with epidemiological studies with more complete mortality observations, and the selection of more active patients in this RCT-derived cohort compared to these other populations.

In summary, the large majority of deaths observed in this young RCT-derived cohort were adjudicated to be MS related (78.3%). Moreover, the excess in deaths observed in the placebo-randomised group were accounted for entirely by an excess in MS-related deaths and, in particular, by deaths due to pulmonary infections. Whether the impact of therapy on mortality is the consequence of early treatment or a larger cumulative exposure to IFNβ-1b cannot be resolved. Regardless, however, these data support the notion that the mortality benefit from IFNβ-1b is due to a treatment-related impact on the MS disease process itself.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DSG has contributed to the design/conceptualisation of the study, analysis/interpretation of the data, and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. ATR has contributed to the analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. GCE has contributed to the design/conceptualisation of the study, analysis/interpretation of the data, and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. GC has contributed to the analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. MK has contributed to the analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. JO has contributed to the analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. MR has contributed to the design/conceptualisation of the study, analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. TO'D has contributed to the analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. SC has contributed to the conceptualisation of study, data acquisition and development and has reviewed the manuscript. KB has contributed to the design/conceptualisation of the study, analysis/interpretation of the data, and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content. VK has contributed to the design/conceptualisation of the study, analysis/interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: The 21Y-LTF study was funded entirely by Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. The first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript were cowritten by a writing group consisting of the authors (DG, AR and GE) and representatives of the sponsor (VK and MR) with input from all coauthors. Medical writing support as directed by the authors was provided by Ray Ashton, of PAREXEL, who was funded by Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Statistical analyses were performed under the direction of GC and KB. The authors individually and collectively attest to the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses.

Competing interests: Douglas S Goodin has received either personal compensation (for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, or speaking) or financial support for scholarly activities from pharmaceutical companies that develop products for multiple sclerosis, including Bayer-Schering Pharma, Merck-Serono, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Anthony T Reder has received either personal compensation (for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, or speaking) or financial support for scholarly activities from pharmaceutical companies that develop products for multiple sclerosis, including Abbott Laboratories, American Medical Association, Astra Merck, Athena Neurosciences, Aventis Pharma, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlex Laboratories, Biogen and Biogen Idec, BioMS Medical Corp., Blue Cross, Blue Shield, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Caremark Rx, Centocor, Inc., Cephalon, Inc., Connectics/Connective Therapeutics, CroMedica Global Inc., Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Genzyme Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoechst Marion Roussel Canada Research, Inc., Hoffman-LaRoche, Idec, Immunex, Institute for Health Care Quality, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC, Kalobios, S NARCOMS, Yale University, Barrow Neurological Institute, National Multiple Sclerosis Society & Paralyzed Veterans of America, “Pain Panel,” Neurocrine Biosciences, Novartis Corporation, Parke-Davis, Pfizer Inc, Pharmacia & Upjohn, Protein Design Labs, Inc, Quantum Biotechnologies, Inc., Questcor Pharmaceuticals Inc., Quintiles, Inc., Serono Sandoz (now Novartis) & Novartis, Sention, Inc., Serono, Shering AG, Smith Kline-Beecham, Berlipharm, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Teva-Marion, and Triton Biosciences. George C Ebers has received consulting fees from Roche, Biopartners, EISAI, MVM Life Science Partners, and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; honoraria as an Executive Committee member of the MS Forum from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; and travel support from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Gary Cutter has received either personal compensation (for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, or speaking) or financial support for scholarly activities from pharmaceutical companies that develop products for multiple sclerosis, including Antisense Therapeutics Limited, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayhill Pharmaceuticals, BioMS Pharmaceuticals, Daichi-Sankyo, Genmab Biopharmaceuticals, Glaxo Smith Klein, PTC Therapeutics, Medivation, Eli Lilly, Teva, Vivus, University of Pennsylvania, NHLBI, NINDS, NMSS, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Inc., Accentia, Bayer, Bayhill, Barofold, CibaVision, Novartis, Diagenix, Consortium of MS Centers, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, Enzo Pharmaceuticals, Peptimmune, Somnus Pharmaceuticals, Teva pharmaceuticals, UTSouthwestern, Visioneering Technologies, Sandoz, and Nuron Biotech, Inc. Marcelo Kremenchutzky has received honoraria (for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, or speaking) or financial support for scholarly activities from Biogen Idec, Teva Neurosciences, Sanofi-Aventis, EMD Serono, Novartis and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Joel Oger has received honoraria, consulting fees, travel, research and/or educational grants from Aspreva, Aventis, Bayer, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Genentech, Schering, Talecris, and Teva Neurosciences. Timothy O'Donnell has received compensation from Bayer for sitting on the adjudication committee for this study and has participated as an investigator for open label, and safety and efficacy trials with Otsuka, Schering, and Bristol-Myers Squibb pharmaceutical companies. Stuart Cook has received personal compensation for consultations or lectures from Merck Serono, Bayer HealthCare, Sanofi Aventis, Neurology Reviews, Biogen Idec, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Genmab and Actinobac Biomed Inc. He has served on Scientific Advisory Boards for Bayer HealthCare, Merck Serono, Actinobac Biomed, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Biogen Idec. Mark Rametta and Karola Beckmann are salaried employees of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Volker Knappertz was a salaried employee of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals at the time of manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval: The pre-planned 21-year long-term follow-up study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01031459) was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice guidelines. Appropriate written informed consent was obtained and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no unpublished data.

References

- 1.Bronnum-Hansen H, Koch-Henriksen N, Stenager E. Trends in survival and cause of death in Danish patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain 2004;127:844–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grytten TN, Lie SA, Aarseth JH, et al. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: results from a 50-year follow-up in Western Norway. Mult Scler 2008;14:1191–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smestad C, Sandvik L, Celius EG. Excess mortality and cause of death in a cohort of Norwegian multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2009;15:1263–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sumelahti ML, Hakama M, Elovaara I, et al. Causes of death among patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010;16:1437–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekestern E, Lebhart G. Mortality from multiple sclerosis in Austria 1970–2001: dynamics, trends, and prospects. Eur J Neurol 2004;11:511–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leray E, Morrissey SP, Yaouanq J, et al. Long-term survival of patients with multiple sclerosis in West France. Mult Scler 2007;13:865–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragonese P, Aridon P, Mazzola MA, et al. Multiple sclerosis survival: a population-based study in Sicily. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:391–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redelings MD, McCoy L, Sorvillo F. Multiple sclerosis mortality and patterns of comorbidity in the United States from 1990 to 2001. Neuroepidemiology 2006;26:102–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liddell FD. Simple exact analysis of the standardised mortality ratio. J Epidemiol Community Health 1984;38:85–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen PK, Vaeth M. Simple parametric and nonparametric models for excess and relative mortality. Biometrics 1989;45:523–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riise T, Gronning M, Aarli JA, et al. Prognostic factors for life expectancy in multiple sclerosis analysed by Cox-models. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:1031–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallin MT, Page WF, Kurtzke JF. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in US veterans. VIII. Long-term survival after onset of multiple sclerosis. Brain 2000;123(Pt 8):1677–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch-Henriksen N, Bronnum-Hansen H, Stenager E. Underlying cause of death in Danish patients with multiple sclerosis: results from the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:56–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degenhardt A, Ramagopalan SV, Scalfari A, et al. Clinical prognostic factors in multiple sclerosis: a natural history review. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:672–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutter G, Reshef S, Golub H, et al. Survival and mortality cause in populations with multiple sclerosis in the United States (MIMS-US) (abstract). Mult Scler 2011;17:S301–2 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1993;43:655–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Interferon beta-1b in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: final outcome of the randomized controlled trial The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. Neurology 1995;45:1277–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodin DS, Reder AT, Ebers GC, et al. Survival in MS: a randomized cohort study 21 years after the start of the pivotal IFNB-1b trial. Neurology 2012;78:1315–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paty DW, Li DK. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. UBC MS/MRI Study Group and the IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1993;43:662–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebers GC, Traboulsee A, Li D, et al. Analysis of clinical outcomes according to original treatment groups 16 years after the pivotal IFNB-1b trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:907–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reder AT, Ebers GC, Traboulsee A, et al. Cross-sectional study assessing long-term safety of interferon-beta-1b for relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology 2010;74:1877–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bronnum-Hansen H, Stenager E, Hansen T, et al. Survival and mortality rates among Danes with MS. Int MS J 2006;13:66–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piantadosi S. Clinical trials: a methodologic perspective. 2nd edn Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, et al. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med 2002;21:2917–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodin DS, Reder AT. Evidence-based medicine: promise and pitfalls. Mult Scler 2012;18:947–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodin DS, Reder AT. Response to the GS Gronseth and E Ashman. Mult Scler 2012;18:1661–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kappos L, Traboulsee A, Constantinescu C, et al. Long-term subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology 2006;67:944–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bermel RA, Weinstock-Guttman B, Bourdette D, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 15-year follow-up study. Mult Scler 2010;16:588–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford C, Goodman AD, Johnson K, et al. Continuous long-term immunomodulatory therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis: results from the 15-year analysis of the US prospective open-label study of glatiramer acetate. Mult Scler 2010;16:342–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bisson GP, Gaolathe T, Gross R, et al. Overestimates of survival after HAART: implications for global scale-up efforts. PLoS One 2008;3:e1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirst C, Swingler R, Compston DA, et al. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a prospective population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:1016–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phadke JG. Survival pattern and cause of death in patients with multiple sclerosis: results from an epidemiological survey in north east Scotland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:523–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.